Abstract

On the basis of an ecological approach, this article analyzes the crime determinants in neighborhoods of Santiago, Chile. It concludes that the concentration of social disadvantages, disorder and physical deterioration, together with the presence of an oppositional subculture, is associated with a greater occurrence of crimes, and that the development of trust among the neighbors operates as a mechanism for the prevention of criminal activities. The article also identifies the implications that the relationship between crime and the characteristics of the neighborhood would have for the design of public policies aimed at preventing and controlling crime at that level. A representative survey was carried out that collected data from 5861 households belonging to neighborhoods of Greater Santiago. Data have also been collected through direct observation of the characteristics of these neighborhoods. The analyses were carried out at the micro-neighborhood (a small territorial space) and neighborhood unit (intermediate territory between the micro-neighborhood and the commune) level, and econometric estimations of count data type were applied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 1969 the team led by Phillip Zimbardo abandoned a car unlocked and without license plates in the streets of the Bronx neighborhood in New York. A car of the same make and similar condition was also abandoned in the streets of Palo Alto, California. The car abandoned in the Bronx was ransacked in a few minutes and within 1 week had been completely destroyed. The car abandoned in Palo Alto did not suffer any robbery in 1 week and the neighbors reported the abandoned car to the police. After Zimbardo damaged with a hammer the car abandoned in Palo Alto, it had the same fate as that in the Bronx (for more details see, for example, Diario El País, 2004; Mójate.es, 2010; Diario NTR Zacatecas, 2011; Tatum, 2013).

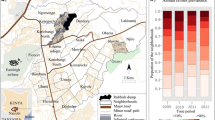

Greater Santiago is a geographical area covering most of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, Chilés national capital city. It includes 35 communes. A commune is the basic geographic unit in the political-administrative organization of Chile. The Chilean levels of government are: national, regional, provincial and communal. The municipality is the political-administrative unit that governs the commune.

The block is the most basic territorial unit used for population identification during censuses. It corresponds to the inner territorial space enclosed by the intersection of normally four streets, drawing a square or a rectangle, without there being in this space a smaller unit corresponding to that same definition.

One hundred and fifteen MNs were not considered for the sampling because they were crossed by highways, large avenues or other landmarks that may affect the neighborhood processes.

The observers were previously trained on the procedure they had to apply in their work, on how to fill out a pre-designed form where they had to annotate the landmarks of the neighborhood, and on the characteristics of the territory they had to observe, for which they were given a detailed map.

For example, Diario El Mundo of Spain mentions that this practice, called ‘Shoefiti’ – joining the words shoe and graffiti – would identify drug dealing sites or the occurrence of a murder by a local gang. According to that same article, in 2003 a circular from the Municipality of the City of Los Ángeles ordered the removal of shoes hanging from wires because they indicated drug-dealing sites (see Diario El Mundo, 2008). On the forum of a website related to fans of the Chilean soccer team ‘Colo-Colo’ – where the fans themselves explain the meaning that, according to them, this practice has – almost all the comments attribute it to marking gang territory, drug sale, or an assault or attack on a member of a rival gang (see Dalealbo.cl., 2013). What is interesting about this forum is that the members of these violent supporter groups – who are often related to community gangs in low-income sectors – are those who give opinions with respect to the meaning of this practice.

Data were analyzed using a Poisison’s distribution (see Hausman et al, 1984; Winkelmann and Zimmermann, 1995; Osgood, 2000; Winkelmann, 2008; Trivedi and Munkin, 2010). A negative binomial model was applied as the variables showed some form of overdispersion. To test the existence of data overdispersion the variance and the mean of the dependent variable were compared, the Pearson statistic was divided by the model’s degree of freedom and the methodology proposed by Cameron and Trivedy (1998, 2001, 2009) was applied. Results of these tests are available upon request.

The models were fitted using the complex survey design.

The aim of this multivariate method is to reveal whether there are subjacent variables in the data that may be causing the variability of the variables considered (Costello and Osborne, 2005). Thus, the factorial analysis method analyzes only the common variance between the selected variables. On the other hand, the principal component analysis is commonly used only as a data reduction method (Costello and Osborne, 2005) aimed at maximizing the total variance in the smallest number of factors.

As the questions used for the construction of the indices have an ordinal character, a polyserial correlations matrix was used with the purpose of approaching the possible underestimation of the factors found. Moreover, as there is the possibility that the questions used to measure trust and subculture could be related to each other, a normalized oblique rotation was used, a technique that allows the factors found to be correlated, tackling the problem mentioned above. Once this analysis had been made, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test was applied, which allows the suitability of the data to carry out a factorial analysis to be measured.

The city map with this identification is available upon request.

Sampson (2004) further argues that the efforts toward the reduction of crime in the neighborhoods must be accompanied by a feeling of legitimacy of the application of the law by the neighbors and, by extension, of the same law and order that are accepted by the majority of society. A contrario sensu, following the same argumentative logic, the lack of this legitimacy will be associated with contexts of greater crime recurrence. The latter concept is close to that of ‘opposing cultures’ used by Sherman (1998), and that of ‘uncivil cultures’ used in this article.

In contrast with the work of Sampson (2003 and 2004) and Sampson et al (2002), which carries out its analysis in relatively extensive neighborhood units, equivalent to the size of an NU in this article, the present study establishes a smaller additional level of analysis – the MN. This allows evidence to be provided on the setting in which these variables would most properly operate, and consequently, of the scale of the interventions oriented at reducing the levels of crime and violence in the neighborhoods.

See, for instance, the description of Chilean Program on Citizen Security such as ‘Plan Cuadrante de Seguridad Preventiva’ (Quadrant Plan of Preventive Security) (Carabineros de Chile, 2003), ‘Barrio Seguro’ (Safe Neighborhood) (DSCMI, 2004), ‘Barrio en Paz’ (Neighborhood in Peace) (Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio del Interior, 2010).

References

Araya, J. (2009) Índice de vulnerabilidad social delictual. La incidencia de los factores de riesgo social en el origen de conductas delincuenciales. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio del Interior, División de Seguridad Pública, Unidad de Estudios.

Araya, J. and Sierra, D. (2002) Influencia de Factores de Riesgo Social en el Origen de Conductas Delincuenciales: Índice de Vulnerabilidad Social Delictual Comunal. Ministerio del Interior, División de Seguridad Ciudadana.

Arias, G.F. (1998) Barrios desfavorecidos en ciudades españolas. En: Foro Vulnerable Neighborhoods, http://habitat.aq.upm.es/bv/agbd09.html.

Asesorías para el Desarrollo (2003) Evaluación de experiencias en La Legua Emergencia y La Victoria. Programa Barrios Vulnerables. Ministerio del Interior, División Seguridad Ciudadana.

Brantingham, P.J. and Brantingham, P. (1998) Environmental criminology: From theory to urban planning practice. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention 7 (1): 31–60.

Brantingham, P.J., Tita, G.E., Short, M.B. and Reid, S.E. (2012) The ecology of gang territorial boundaries. Criminology 50 (3): 851–885.

Brantingham, P.J. and Brantingham, P.L. (1981) Environmental Criminology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cameron, A.C. and Trivedi, P. (1998) Regression Analysis of Count Data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, C. and Trivedi, P. (2001) Essentials of count data regression. En: B.H. Baltagi (ed.) A Companion to Theoretical Econometrics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, pp. 331–348.

Cameron, C. and Trivedi, P. (2009) Microeconometrics using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Candina, A. (2003) Los barrios vulnerables de Santiago. Unpublished manuscript.

Carabineros de Chile (2003) Manual de Aplicación ‘Plan Cuadrante de Seguridad Preventiva de Carabineros de Chile’. Santiago, Chile: Carabineros de Chile, Dirección General.

Costello, A. and Osborne, J. (2005) Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 10 (7): 1–9.

Dalealbo.cl. (2013) Foro ‘Zapatillas colgando de los cables … que significa eso???’ http://www.dalealbo.cl/foro/ocio/45952-zapatillas-colgando-de-los-cables-que-significa-eso.html, accessed May 2013.

Diario El Mundo (2008) El lenguaje secreto de las zapatillas colgantes. Edition of Saturday 22 March 2008, http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2008/03/21/madrid/1206087762.html, accessed May 2013.

Diario El País (2004) Tribuna: ‘La Teoría de las Ventanas Rotas’. Edición del 18 de Octubre de 2004, http://www.elpais.com/articulo/cataluna/teoria/ventanas/rotas/elpepiautcat/20041018elpcat_7/Tes, accessed November 2011.

Diario NTR Zacatecas (2011) Las ventanas mexicanas rotas. Edition of 18 October 2011, http://ntrzacatecas.com/editoriales/opinion/2011/10/18/las-ventanas-mexicanas-rotas/, accessed May 2013.

División de Seguridad Ciudadana, Ministerio del Interior (DSCMI) (2004) Diagnostico de la Seguridad Ciudadana en Chile. Foro de Expertos en Seguridad Ciudadana. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio del Interior.

Earls, F., Brooks-Gunn, J., Raudenbush, S. and Sampson, R. (1994) Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods: Community Survey, 1994–1995. ICPSR 2766. US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

Eck, J. (1998) Preventing crime at places. In: L. Sherman, D. Gottfredson, D. Mackenzie, J. Eck, P. Reuter and S. Bushway (eds.) Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising. A report to the United States Congress. USA: University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology.

Frey, A. (2009) ‘Situación delictual en comunas del Gran Santiago: delitos de mayor connotación social y droga en base a estadísticas policiales y encuestas de victimización’. Nota Técnica Nº2. Proyecto de Investigación ‘Crimen y Violencia Urbana: aportes de la ecología del delito al diseño de políticas públicas’.

Frühling, H. and Gallardo, R. (2012) Programas de seguridad dirigidos a barrios en la experiencia chilena. Revista INVI 27 (74): 149–185, Santiago, Chile: Instituto de la Vivienda, Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Universidad de Chile.

Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio del Interior (2010) Chile Seguro. Plan de Seguridad Pública 2010-2014. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio del Interior.

Hausman, J., Hall, B. and Griliches, Z. (1984) Econometric models for count data with an application to the patents – R and D relationship. Econometrica 52 (4): 909–938.

Heinemann, A. and Verner, D. (2006) Crime and Violence in Development: A Literature Review of Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington DC: The World Bank. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Nº 4041.

Kelling, G. and Coles, C. (1996) Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in our Communities. New York: The Free Press.

Lunecke, A. and Ruíz, J.C. (2006) Barrios críticos en materia de violencia y delincuencia: marco de análisis para la construcción de indicadores de diagnóstico. Santiago, Chile: Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

Manzano, L. (2009) Violencia en barrios críticos. Explicaciones teóricas y estrategias de intervención basadas en el papel de la comunidad. Santiago, Chile: RIL.

Mójate.es (2010) Teoría de las ventanas rotas. En: http://www.mojate.es/index.php/ipor-que/152-teoria-de-las-ventanas-rotas.html, accessed May 2013.

Nespolo, R. (2011) ‘La construcción diferente de los procesos de inseguridad en los distintos grupos socioeconómicos presentes en la Región Metropolitana de Santiago’, ppt. Ponencia en Conferencia Internacional Violencia en Neighborhoods en América Latina: sus determinantes y políticas de intervención. Santiago, Chile, 5 and 6 October 2011.

Olavarría, M. (2006) El crimen en Chile: una mirada desde las víctimas. Santiago, Chile: Ril Editores.

Olavarría, M. (2010a) Victimización delictual en Chile, 2003–2008. Capitulo Criminológico 38 (3): 233–254.

Olavarría, M. (2010b) Lecciones aprendidas en los estudios impulsados por la División de Seguridad Pública, 2002–2009. Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio del Interior, División de Seguridad Pública.

Osgood, W. (2000) Poisson-based regression analysis of aggregate crime rates. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 16 (1): 21–43.

Qué Pasa (2009) Santiago Ocupado. Qué Pasa, No. 1997, 17 July, pp. 10–21.

Sampson, R. (2003) The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 46 (3): 53–64.

Sampson, R. (2004) Neighborhood and community: Collective efficacy and community safety. The New Economy, 11, pp. 106–113.

Sampson, R., Morenoff, J. and Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002) Assessing ‘neighborhood effects’: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 443–478.

Sampson, R., Raudenbush, S. and Earls, F. (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Revista Science 277 (5328): 918–924.

Shaw, C. and McKay, H. (1942) Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago, IL: University Chicago Press.

Sherman, L. (1998) Communities and crime prevention. In: L. Sherman, D. Gottfredson, D. Mackenzie, J. Eck, P. Reuter and S. Bushway (eds.) Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising. A report to the United States Congress prepared for the National Institute of Justice by the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Maryland at College Park.

Sherman, L., Gottfredson, D., Mackenzie, D., Eck, J., Reuter, P. and Bushway, S. (1998) Preventing Crime: What Works, What doesn’t, What’s Promising. A report to the United States Congress prepared for the National Institute of Justice by the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Maryland at College Park.

Spencer, C. (2004) Informe para el Programa Comuna Segura Compromiso 100. Ministerio del Interior, División de Seguridad Ciudadana. Santiago, Chile: Fundación AVEC.

Tatum (2013) Ventanas Rotas; http://www.tatum.es/blogosferarrhh/Paginas/PostsC.aspx?PmId=574, accessed May 2013.

Terra (2002) Las calles más peligrosas de Santiago. Edición del 16 de Julio de 2002. En: http://www.terra.cl/actualidad/index.cfm?id_cat=302&id_reg=149201, accessed May 2013.

Trivedi, P. and Munkin, M. (2010) Recent development in cross section and panel count models. In: A. Ullah and D. Giles (eds.) Handbook of Empirical Economics and Finance. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 87–131.

Wilson, J.Q. and Kelling, G.L. (1982) Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, March. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/4465/, accessed November 2011.

Winkelmann, R. (2008) Econometric Analysis of Count Data. 5th edn. Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

Winkelmann, R. and Zimmermann, K. (1995) Recent developments in count data modelling: Theory and application. Journal of Economic Surveys 9 (1): 1–24.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2004) The Economic Dimension of Interpersonal Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Injuries and Violence Prevention, World Health Organization.

Zimbardo, P. (2013) Anonymity of place stimulates destructive vandalism, http://www.lucifereffect.com/about_content_anon.htm, accessed June 2013.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the comments on preliminary versions of this document made by colleagues attending Workshops on Project SOC09, Messrs. Hugo Fruhling, Javier Nuñez, Ricardo Tapia, Roberto Gallardo, and Mrs Ximena Tocornal. We thank those attending the Workshops at the Subsecretaría de Prevención del Delito on 15 December 2011, and at the Programa Barrio en Paz on 4 January 2012, and those attending the Second Workshop on Analysis and Modeling of Security on 19 January 2013. We are grateful for additional comments from Dr Fruhling on August 2013 and comments from two anonymous referees of CPCS. Any errors are the authors’ responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the SOC 09 Project ‘Crimen y Violencia Urbana: aportes de la ecología del delito al diseño de políticas públicas’ (Urban Crime and Violence: contributions of the ecology of crime to the policy design), financially suported by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT) of Chile (Chile’s National Commission of Scientific and Technological Research) in the ‘Anillos de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales’ modality (Team Research in Social Sciences).

Appendices

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olavarría-Gambi, M., Allende-González, C. Crime in neighborhoods: Evidence from Santiago, Chile. Crime Prev Community Saf 16, 205–226 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2014.7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2014.7