Abstract

This study applies social exchange theory to explain how the perception of organizational politics (POP) affects organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). In particular, the current study hypothesizes that moral efficacy negatively mediates the relationship between POP and OCB. Moreover, this study investigates how perceived insider status moderates the negative effect of POP on moral efficacy. This study uses a sample of 392 supervisor–subordinate dyads from touring companies at two different time periods in Southern China. Results support study hypotheses and provide new research directions for studying organizational politics and OCB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last three decades, organizational politics has received wide-ranging attention in basic and applied research from the theoretical and practical perspectives. However, practitioners and academicians have different views on the definition of organizational politics. Several scholars argue that organizational politics is an extreme social phenomenon (Bies and Tripp 1995; Cobb 1996; Mouzelis 2017; Pfeffer 1992), while others believe that this idea is a workplace phenomenon and represents the political environment of an organization (Cropanzano et al. 1995; Kacmar and Ferris 1991; Nica et al. 2016). Others argue that organizational politics is an unacceptable attempt of employees to achieve personal benefits at the expense of organizational benefits (Beehr and Gilmore 1995; Ferris et al. 2000; Ferris and Kacmar 1992; Mansbridge 2018). Several scholars, experts, and practitioners are profoundly interested in studying all aspects of organizational politics (Erin and Landells 2017; Miller et al. 2008). Therefore, perception of organizational politics (POP) is referred to in the assessment of supervisors and colleagues who have experienced self-service behavior (Ferris et al. 2000; Saleem 2015). Previous studies have suggested that POP has a damaging impact on organizational and employee outcomes in terms of employee commitment, satisfaction, and job performance. Moreover, POP is allegedly related to workplace stress, employee burnout, and turnover intentions (Chang et al. 2009; Tong et al. 2015; Vigoda-Gadot and Talmud 2010).

To the best of our knowledge, previous studies, particularly in the field of tourism, have focused minimally on the different mechanisms and processes that can facilitate the reduction of the damaging effects of POP on positive outcomes. However, the present study is relatively unique and explains the impact of POP on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) by applying a moderated mediation model. To determine the relationship between POP and OCB, this study aims to answer the following questions: (1) What is the nature of the relationship between POP and OCB? (2) How does the mediating mechanism explain the direction of this relationship? (3) What is the role of moderation in this relationship? (4) To what extent does a moderated mediation model affect the relationship between POP and OCB?

To answer these questions, this study attempts to supplement the existing literature from four aspects. First, the current study expands organizational politics research, particularly in the tourism literature, by exploring the destructive effects of POP on OCB. Second, this study extends the existing research on POP by introducing a new mediator (i.e., moral efficacy) to establish the relationship between POP and OCB. Third, we introduce the potential moderating role of perceived insider status (PIS) between POP and moral efficacy to weaken this negative relationship. The buffering effect of PIS may occur by gaining personal space and employee acceptance in the organization (Li et al. 2014; Masterson and Stamper 2003). Lastly, this study extends the existing research by simultaneously incorporating moderating and mediating variables to reduce the negative effects of POP on OCB through a moderated mediation. Given that moral efficacy is a belief that motivates employees to avoid harmful politics within an organization (Edmondson 1999; Heald 2017) and PIS refers to a person’s perception of the status of insiders (versus outsiders) within an organization, this study concentrates on the association between employees and organizations and imitate the extent to which individuals gain personal space and acceptance in the organization (Wang and Kim 2013).

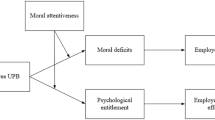

This study anticipates that research on organizational politics is particularly important in the context of China’s tourism industry because employees are relatively weak in expressing their behaviors and actions in the workplace (Zhang et al. 2011). Moreover, we apply social exchange theory (SET) to explain the relationship between POP and OCB (see Fig. 1). SET is one of the most influential conceptual paradigms used to understand an individual’s workplace behavior (Blau 1964).

Theoretical foundation and hypothesis development

In the present study, citizenship behavior is indirectly associated with any incentive-based system (Organ 1988). Given that OCB is not part of their employees formal work contract agreement, the following question should be answered: Why does an employee have to demonstrate this behavior to perform additional work? This question can be addressed by applying SET (Blau 1964). Accordingly, SET is considered one of the most influential conceptual paradigms in understanding an individual’s behavior in an organization. SET dates back to the 1920s (Malinowski 1922) and combines various disciplines, such as anthropology (Firth 1967), social psychology (Homans 1958), and sociology (Blau 1964). Although opinions vary on the interpretation of SET, scholars agree that the obligations resulting from social exchanges include a series of interactions (Emerson 1976). The interpretation value of SET is reflected in many fields, such as social power (Molm et al. 1999), network (Brass et al. 2004), board independence (Westphal and Zajac 1997), organizational justice (Schminke et al. 2015), psychological contract (Rousseau 1995), and leadership (Sousa and van Dierendonck 2017). One of the basic principles of SET is that relationships grow in trust, loyalty, and mutual commitment. To achieve such growth, both parties must abide by certain “exchange rules” (Emerson 1976). These rules form the normative definition of the situation in which individuals are formed or adopted in exchange relationships. The exchange of norms and rules is the “guideline” for the exchange process.

Therefore, this study uses the exchange rules and principles that researchers rely on to propose the application of SET in the study model. The reason is that social exchange is one of the most important theoretical frameworks for explaining individual behavior in hospitality work (Blau 1964). One of the main characteristics of SET is the connection among individuals. Over time, development has become a result of trustworthiness, dedication, commitment, and shared responsibility. For such mutual commitments, individuals should follow certain communication norms (Emerson 1976). Therefore, exchange rules constitute the basic principle of the exchange process. Mutual communication involves interpersonal interactions, in which one person’s behavior causes another person’s reaction. If an individual hurts or indulges in abusive behavior, then those who receive such a treatment will respond accordingly.

Advocates of SET assert that this type of exchange has positive and negative effects on reciprocal relationships (Shao et al. 2018). On the one hand, social exchange relationships evolve and produce beneficial results when employers “care about employees.” On the other hand, organizational politics is considered a destructive phenomenon that can undermine citizenship behavior (Stamper and Masterson 2002). Consequently, scholars are interested in studying to the method of reducing the negative impact of organizational politics. Therefore, the present study attempts to address the negative effects of POP associated with OCB. Thus, SET states that OCB stems from altruistic motivation, while a good organizational environment encourages employees to adopt citizenship behavior (Organ 1988; Pereira et al. 2015).

POP and moral efficacy

The concept of POP is derived from the definition that an employee considerably struggles for his/her personal benefit at the price of an organizational goal. In this context, moral efficacy is an influential determinant that deepens employee ethics in the form of loyalty to the broad benefits of the organization (Ko 2017). Therefore, moral efficacy becomes extremely important in highly politicized organizations because these organizations are replete with uncertainty (Onyango 2017). Moral efficacy often inhibits employees from becoming actors within organizational politics (Acar 2015). In addition, moral efficacy can facilitate the promotion of employees’ OCB. Consequently, the moral performance of employees can be enhanced because they believe that the organization accepts their valuable opinions (Bliuc et al. 2015; Hornstein 1986). In addition, moral efficacy provides a safe and honorable work environment without any psychological stress (Chang et al. 2009).

However, highly politicized organizations are often complex and experience uncertainty. These politicized perceptions lead employees to their own interests by undermining moral values, including commitments and loyalty (Martin and Tao-Peng 2017). From the perspective of SET, highly politicized organizations can undermine employee confidence in welfare-based incentives or reward systems (Rosen et al. 2006). In this situation, POP has a negative impact on employee motivation (Shrestha and Mishra 2015). Therefore, we develop our hypothesis as follows:

H1

POP is negatively associated with moral efficacy.

Mediating role of moral efficacy

OCB is an unpaid volunteer behavior within an organization, although highly politicized organizations often discourage employees from participating in voluntary actions in terms of outcome and career advancement (Milliken et al. 2003). Citizenship behavior is related to the voluntary nature of additional work for organizational development and is completely different from regular work behavior. Citizenship Behavior depends on whether employees exercise their additional responsibilities to improve the organization rather than politicizing their additional responsibilities (Chen et al. 1998; Lam et al. 2016). Therefore, when employees feel that their intentions in citizenship behavior are improperly and inappropriately appreciated in a politicized organizational environment, this thinking inhibits their usual civic behavior (Salomonsen et al. 2016).

However, employees with high moral efficacy have minimal fear of their own interests when expressing citizenship behavior (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Moral efficacy also demonstrates trust and participation in the organization, thereby fostering OCB (Bliuc et al. 2015; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). SET indicates that a person’s behavior depends mainly on the quality of the relationship between an individual and organization (Blau 1964). If employees’ perceptions of the organizational environment are positive, then they will attempt to develop good relationships with the organization in social exchanges, thereby stimulating good citizenship behavior (Ing-Long et al. 2014; Purba et al. 2015). The characteristics of the organizational environment are particularly important if employees are involved in citizenship behavior (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008). Organizations with a highly politicized environment often direct employees to emphasize the negative and uncontrollable aspects of problems (Ennser-Jedenastik 2015; Ferris et al. 2002). Moral efficacy may play a negative intermediary role in the relationship of POP with citizenship behavior because the independent and dependent variables are inherently contradictory.

Therefore, employees in a highly politicized work environment demonstrate behavior related to resource conservation, robust control mechanisms, and actions to maintain the status quo (Staw et al. 1981). Moreover, employees with low moral performance in a politicized work environment are often uninterested in challenging the politicized situation in the organization (Bliuc et al. 2015). In this context, POP devalues employees who demonstrate loyalty and commitment to express their moral efficacy (Ko 2017). Previous studies have determined that moral efficacy mediates the relationship of ethical (Nakano 2007; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009) and change-based leadership (Bruning 2013; Detert and Burris 2007) with OCB. Therefore, we propose our hypothesis as follows:

H2

Moral efficacy negatively mediates the relationship between POP and OCB.

Moderating role of perceived insider status

The present study proposes that PIS may limit the adverse effects of POP because of the former’s moderating influence. Organizations may be able to increase employee awareness of control and ultimately, insider status can mitigate the effects of uncertainty associated with POP (Miller et al. 2008; Onyango 2017). Several studies have shown that PIS is an important determinant of the perception of performing additional tasks to minimize the risks associated with adverse conditions (Li et al. 2014; Masterson and Stamper 2003). Organizations can encourage employees by differentiating them into insiders and outsiders. Such differentiation can happen when an organization introduces appreciation and reward mechanisms for performers within the firm (Stamper and Masterson 2002). PIS guides employees to control the environment and build trust in organizational authority (Greene 2014). Insider support enables employees to receive additional organizational assistance to promote good relationships within an organization (Greene 2014; Stamper and Masterson 2002). Consequently, PIS promotes additional work behavior in an organization. A previous study has shown that trust and social support for colleagues mitigate the negative impact of POP on employees (Vigoda-Gadot and Talmud 2010).

Therefore, the uncertainty caused by POP, which is related to moral efficacy, is reduced when employees think that they are insiders. In the case of the perceived high insider status, the negative association of POP with employee moral efficacy and OCB is expected to decrease, thereby resulting in a relatively favorable situation, in which employees perceive moral efficacy to play an additional role. By contrast, if PIS is low, then the negative relationship strengthens and employees feel the risk of exercising their citizenship behavior (Li et al. 2014). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses.

H3

PIS moderates the negative relationship between POP and moral efficacy, thereby making this relationship weaker for employees with higher PIS than those with lower PIS.

H4

PIS moderates the negative mediating relationship between POP and OCB through moral efficacy, thereby making this relationship weaker for employees with higher PIS than those with lower PIS.

Methods

Sampling and data collection procedures

The present research was performed using 11-month lagged design in touring agencies located in Southern China from October 2016 to September 2017. Citizenship behavior is important in touring agencies because employees of these companies are often involved in exploring new ideas to attract their customers (Bstieler and Hemmert 2008). Similarly, POP is also common in the tourism sector. Therefore, the relationship between POP and OCB should be investigated and explained. The present study took the sample from touring agencies. The data for this study were collected at two time points with a time interval of 11 months. This research determined that the two-wave method showed substantial differences in the time interval between data collection, often from 3 weeks (Burris et al. 2008) to 10 months (Detert and Burris 2007).

By involving both process and the contingent impact, this study tested our proposed moderated mediation model over an 11-month timeframe to provide respondents with opportunities to properly observe, evaluate, decide, and act. In the first step of the study, data on POP, moral efficacy, and demographic factors were collected from employees of different touring agencies. In the second stage, data on PIS and OCB were collected from employees and their immediate supervisors, respectively.

This study used structured questionnaires to collect data from the respondents. The structured translation process was used (Khan and Ali 2018). Initially, the questionnaire was designed in English and translated thereafter into Chinese by a professional interpreter. The Chinese version of the questionnaire was reviewed by two Chinese post-doctoral students who are proficient in English. In the first phase, the questionnaires were randomly distributed among 567 employees through the human resource departments of the respective agencies. In this phase, 421 of the 567 employees provided their responses to the prescribed questionnaire. In the survey’s second phase, the questionnaires were distributed to the same 421 respondents in the first phase and 102 immediate supervisors. This time, 346 employees and 79 direct supervisors provided their responses. After reviewing the responses received on the basis of mismatched or missing information, the final sample comprised 321 subordinates and 71 supervisors.

Measurement

POP

We used a 12-item scale developed by Ferris and Kacmar (1992) to measure POP. The responses were obtained using a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Moral efficacy

We used the change efficacy four-item scale developed by Wanberg and Banas (Wanberg and Banas 2000) to measure moral efficacy. We collected the responses using a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (‘‘strongly disagree’’) to 5 (‘‘strongly agree“).

PIS

We used a six-item scale developed by Stamper and Masterson (2002). To capture the responses, we used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

OCB

We used the Chinese version of the OCB scale of three dimensions (i.e., altruism, five items; conscientiousness, four items; and civic virtue, four items) as developed by (Farh et al. 1997). The responses were collected using a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Results

Demographics

Each supervisor rated an average of 4.5 subordinates. Out of 321 subordinates, 57.4% were male, while 40.3% and 25% were 21–30 and 31–40 years old, respectively. The average work tenure in the organization was 7.5 years. Out of the 79 supervisors, 70.6% were male, while 41.5% and 26.5% were 31–40 and 41–50 years old, respectively. The average job tenure of supervisors in an organization was 14.8 years (see Table 1).

Reliability and validity

This study calculated the fit index to understand the model fit in our data set (Hair et al. 2005). The value of x2/df should be below 2.5, while the values of the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) should be above 0.9 for good model fit. Furthermore, if the approximation root mean square error (RMSEA) is below 0.08, then the model is considered suitable (Podsakoff et al. 2003; Xiongfei et al. 2018). This study analyzed construct validity and reliability through CFA. Table 2 shows that Cronbach’s alpha is above 0.8, thereby indicating that the reliability of the scales is good and appropriate (Nunnally and Berstein 1978).

For each construct, the average variance extracted (AVE) is above 0.63 and represents good convergent validities (Bagozzi and Yi 1988). We tested the discriminant validity by comparing the AVE square root of each construct. Table 3 shows that the AVE square roots of the two data sets are higher than all the corresponding correlation coefficients, thereby indicating that the scales have good discriminant validities. Although we used two-wave study data in our research, the self-reported data rarely have the opportunity to be biased by common methods.

In addition, we used two statistical analysis methods proposed by Podsakoff et al. (2003) to curtail the probability of common method bias. The results of the three factors showed a variance of 36.1% in the data set. Thus, common method bias is not a serious issue. To evaluate the model fit, we used the Chi-square fit index, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. The results indicate an acceptable model fit (χ2 (550) = 1075.12, p ≤ 0.01; CFI = 0.963, TLI = 0.960; RMSEA = 0.049).

Hypothesis testing

We used the SPSS Process Macro (Hayes 2013) to analyze the hypotheses presented in our conceptual model. Table 4 shows the results obtained, which are divided into three components: (a) the model has independent and dependent variables, (b) analysis of mediating direct effects, and (c) analysis of conditional indirect effects. From the independent and dependent variable models, we observed that POP negatively predicted moral efficacy (β = − 0.58, p < 0.001), moral efficacy positively predicted OCB (β = 0.27, p < 0.001), and POP negatively predicted OCB via moral efficacy (β = − 0.52, p < 0.001). These results illustrated the significant mediation of moral efficacy between POP and OCB. Therefore, H1 and H2 are supported.

In addition, the interaction between POP and PIS had a significant effect on moral efficacy (β = 0.34, p < 0.01). This result indicated that the relationship between POP and moral efficacy was moderated by PIS (see Fig. 2). The analysis of the indirect effects of conditions determined that two of the three indirect effects of condition (depending on the mediator values at the mean and at the − 1 standard deviation) were negative and significantly different from 0. Therefore, H3 and H4 are supported.

Discussion

The academic literature should explore the impact of POP on OCB and reduce the damaging aspects of politics on citizen behavior. To address the current gap in academic knowledge, our findings provide information on the nature of the relationship between POP and OCB. The current results further describe the intermediary mechanism (i.e., moral efficacy) that establishes such relationship and represents the buffering impact of PIS. In H1, POP was predicted to be negatively related to moral efficacy.

This study findings support the hypothesis (i.e., H1) because employees in highly politicized organizations primarily protect their immediate and personal interests rather than the overall interests of the organization (Mansbridge 2018). Moral efficacy does not claim that personal interests take precedence over organizational interests, which is contrary to individual morality (Lam et al. 2016). In H2, moral efficacy negatively mediates the relationship between POP and OCB. Our results confirm study prediction that moral efficacy has a negative mediating effect on the relationship between POP and OCB. Moral efficacy is a key psychological determinant (May et al. 2014) and this psychological state is adversely affected by a highly politicized work environment.

In H3, the buffering effect of PIS was predicted to affect the relationship between POP and moral efficacy. That is, employees with high PIS levels weaken the negative relationship. Similarly, H4 predicts that PIS moderates the mediating relationship between POP and OCB through moral efficacy, which weakens at high levels of PIS. Our results support this hypothesis by showing the buffering effect of PIS on mediating the relationship between POP and OCB. The PIS moderating effect mitigated the negative relationship between POP and moral efficacy and reduced the negative mediating relationship between POP and OCB via moral efficacy. Therefore, the use of a moderated mediation model is consistent with the findings of a previous study in clarifying the predictive model of citizen behavior (Detert and Burris 2007).

Theoretical implications

This study has several theoretical contributions to the development of new directions in the POP and OCB literature.

First, the present study uses the affect-laden cognition perspective and SET to strengthen the understanding of POP and provide a theoretical framework for assessing the key political environmental antecedents of citizen behavior. For example, the mediating role of moral efficacy generates knowledge of how POP affects OCB, thereby enhancing researchers’ understanding of the underlying process by which employees identify their political environment to adjust their civic behavior.

Second, SET argues that social exchange is as important as economic exchange (Blau 1964). Economic exchanges are often based on a contractual method and specified in monetary terms, whereas social exchanges are referred to as purely non-specific responsibilities without mentioning any time frame (Deckop et al. 2003). In a healthy and non-politicized work environment (Özduran and Tanova 2017), employees are often willing to assume additional responsibilities despite a clear personal interest. Therefore, the present study enhances our understanding of the application of SET in our proposed study model by fostering citizenship behavior in the workplace to address social aspects in the social exchange process.

Third, this study identifies the moderating effect of PIS by analyzing its role in the indirect relationship between POP and OCB. Previous studies have suggested that POP and OCB are opposite in nature and actions (Ferris and Kacmar 1992; Li et al. 2014). However, the current study used PIS as a moderator to reduce the inverse relationship between POP and OCB, thereby showing that POP and OCB are not often opposite in nature and action. The nature of this relationship can be changed by enhancing the insider status of employees in an organization. Therefore, when an organization provides employees with considerable insider status, the latter expresses willingness to do additional work beyond the prescribed duties (Feldman and Weitz 1991).

Fourth, this study posits that moral efficacy is a mediating variable (motivational mechanism) between POP and OCB. Moral efficacy motivates employees’ social values. Therefore, moral efficacy is the key psychological driving force to encourage employees to reduce the negative impact of organizational politics by promoting citizen behavior.

Fifth, we use a moderated mediation model to test our hypotheses on the basis of data from Chinese touring agencies. Accordingly, our research provides a theoretical basis and evidence for the unique relationship between organizational work environment and citizenship behavior and expands our understanding of how this relationship functions.

Lastly, this study investigates the relationship between POP and OCB behavior in the Chinese context to reproduce the results of previous research in the Western cultural context (Detert and Burris 2007), thereby promoting cross-cultural external validity. The present study is consistent with the results of previous studies in Western countries, thereby indicating the applications and effects of organizational politics and OCB, which often oppose each other (Detert and Burris 2007). Although the present study’s arguments are not culturally specific, the Chinese culture is based on collectivism rather than individualism (Ali et al. 2018). Thus, the Chinese people have a high degree of collectivism and mutual affiliations. Compared with the Western context, PIS may have a high impact on the Chinese people.

Practical implications

We believe that the results of the present study have practical importance to the tourism and hospitality industry because these results broaden our understanding of the predictors of citizen behavior. This study shows that citizenship behaviors are the result of situational determinants, such as POP; and PIS through motivational and psychological factors, such as moral efficacy. Therefore, this study suggests several steps in organizing and managing actions that promote OCB.

First, the tourism industry leadership should act appropriately to ensure an enabling working environment for employees and distant from organizational politics because politics obstructs the business development process. These corrective actions can include transparency, open access to information, open communication, accountability, and a good incentive system to reduce the destructive aspects that are often associated with organizational politics (Ferris et al. 2002; Onyango 2017).

Second, PIS is an encouraging factor for employees. When employees think that they are an important component of an organization, they prefer to work to protect the interests of the organization rather than the individual. Therefore, tourism management should have clearly differentiate the perceptions related to the insider and outsider statuses of employees (Li et al. 2014; Greene 2014). To improve the understanding and perceptions of the insider status of employees within an organization, leadership can also arrange training and counseling workshops for the former (Greene 2014; Stamper and Masterson 2002).

Third, the present study also encourages the hospitality leadership to consider individuals with proactive personality traits in the selection process. A previous study has shown that individuals with high proactive personality traits behave in a considerably civilized manner and avoid participating in organizational politics (Kim et al. 2009).

Fourth, the present study shows that moral efficacy plays an important role in promoting OCB, although POP has a negative impact on moral efficacy and OCB. Therefore, to cultivate moral efficacy among employees, touring agencies can curtail the negative impact of POP on moral efficacy through ethical leadership proposed by previous studies (Detert and Burris 2007; Lin et al. 2016; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009).

Lastly, a reasonable compensation system for civilized employees can improve the moral efficacy among employees. Therefore, management should introduce an incentive-based system to foster a civic culture within an organization. Consequently, reward-based systems in organizations facilitate the mitigation of POP among employees and encourage and enhance their social and moral values.

Limitations and future research

The present study has a few limitations. First, this research is a two-wave panel study. In this type of research, the problem of data contamination is relatively low. Moreover, common method variance is not a serious issue because data are collected from different data sources at different time points by controlling demographic variables.

Second, this study’s small sample size, which is based on the employees of tourism agencies in one country (China), may be an empirical weakness. Accordingly, such sample size can limit the generalizability of the results. Moreover, small sample sizes produce conservative statistical tests of theoretical relationships, particularly in the theoretical frameworks that include interaction effects (Bouckenooghe et al. 2014). However, large sample sizes can be included in future research. Although the theoretical arguments presented in this study are not industry-specific, our single-industry design also limits our ability to analyze the relevant industries and related factors, such as the level of competition in external markets (Porter 1996). This competitive rivalry makes employees considerably willing to accept the pressure of organizational politics and damaging effects of the internal political environment (Lahiri et al. 2008). This result can mitigate the harmful effects of such an environment on the employees’ OCB.

Third, this study used the collected data of OCB as a first order rather than dividing it into two dimensions (i.e., individual and organizational behavior). These two dimensions in a second order may have different treatments for explaining the relationship between POP and OCB through moral efficacy (Liang et al. 2012). However, future researchers can study the impact of POP on the two dimensions of OCB by adopting a second-order measurement scale related to personal and organizational OCB.

Fourth, there is also a limitation that perceptions of politics and citizenship behaviors have a different frame of reference. In theoretical debates, politics refers to a person’s behavior, while organizational citizenship refers to the behavior of an entire organization. For example, an individual’s “social behavior” is different from his/her “organizational behavior” (Brief et al. 1993). Therefore, future research can address this aspect by allowing respondents to explicitly consider POP and OCB of different social entities.

Lastly, the impact of cultural factors may be affected in this study. The theoretical arguments for this study are not specific to a country, although China tends to avoid risks (Hofstede 2001; Khan et al. 2018). Therefore, employees may be particularly sensitive to the stress associated with political behavior. In our research context, resources may be substantially beneficial to reduce the negative impact of these behaviors on OCB. In addition, the dominance of the collectivism that marks the Chinese culture may affect our research results. Therefore, cross-country research should compare the relative importance of POP to enhance the tendency to adopt informally demanding behaviors in different cultural contexts.

Conclusion

The present study provides insights related to POP and OCB by using PIS as an important boundary condition and combining moral efficacy to establish a mediating role in the relationship between POP and OCB. This study has many important implications for guiding managers and decision-making authorities in the tourism and hospitality industry. The current study provides guidance to reduce the destructive aspects of POP by promoting OCB in the tourism sector. In addition, the present study provides new directions for future investigations to reveal the underlying processes that can facilitate OCB.

References

Acar, Y. G. (2015). Collective action intentions: The role of empowerment and identity politicization. Claremont: The Claremont Graduate University.

Ali, A., Wang, H., & Khan, A. N. (2018). Mechanism to enhance team creative performance through social media: A transactive memory system approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 91, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.033.

Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Beehr, T. A., & Gilmore, D. C. (1995). Political fairness and fair politics: The conceptual integration of divergent constructs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 16–28.

Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. (1995). Beyond distrust: Getting even and the need for revenge. In T. T. Tyler & R. M. Karmer (Eds.), Trust in organisations (pp. 246–260). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchanges and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Bliuc, A.-M., McGarty, C., Thomas, E. F., Lala, G., Berndsen, M., & Misajon, R. (2015). Public division about climate change rooted in conflicting socio-political identities. Nature Climate Change, 5, 226–229.

Bouckenooghe, D., De Clercq, D., & Deprez, J. (2014). Interpersonal justice, relational conflict, and commitment to change: The moderating role of social interaction. Applied Psychology, 63(3), 509–540.

Brass, D. J., Galaskiewicz, J., Greve, H. R., & Tsai, W. (2004). Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 795–817.

Brief, A. P., Butcher, A. H., George, J. M., & Link, K. E. (1993). Integrating bottom-up and top-down theories of subjective well-being: The case of health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 646.

Bruning, N. (2013). Leadership development and global talent management in the Asian context: An introduction. Asian Business & Management, 12(4), 381–386.

Bstieler, L., & Hemmert, M. (2008). Influence of tie strength and behavioural factors on effective knowledge acquisition: A study of Korean new product alliances. Asian Business & Management, 7(1), 75–94.

Burris, E. R., Detert, J. R., & Chiaburu, D. S. (2008). Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 912–922.

Chang, C.-H., Rosen, C. C., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 779–801.

Chen, X.-P., Hui, C., & Sego, D. J. (1998). The role of organizational citizenship behavior in turnover: Conceptualization and preliminary tests of key hypotheses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 922–931.

Cobb, J. (1996). Determinism, affirmation, and free choice. The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 25(1), 9–17.

Cropanzano, R. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Bozeman, D. P. (1995). The social setting of work organizations: Politics, justice, and support. Organizational politics, justice, and support (pp. 1–8). Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Deckop, J. R., Cirka, C. C., & Andersson, L. M. (2003). Doing unto others: The reciprocity of helping behavior in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 47, 101–113.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 869–884.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383.

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2(1), 335–362.

Ennser-Jedenastik, L. (2015). The politicization of regulatory agencies: Between partisan influence and formal independence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26(31), 507–518.

Farh, J.-L., Earley, P. C., & Lin, S.-C. (1997). A cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese society. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 421–444.

Feldman, D. C., & Weitz, B. A. (1991). From the invisible hand to the gladhand: Understanding a careerist orientation to work. Human Resource Management, 30, 237–257.

Ferris, G. R., Adams, G., Lolodinsky, R. W., Hochwarter, W., & Ammeter, A. P. (2002). Perceptions of organizational politics: Theory and research directions (Vol. 1, pp. 179–254). Oxford: Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Ferris, G. R., Harrell-Cook, G., & Dulebohn, J. H. (2000). Organizational politics: The nature of the relationship between politics perceptions and political behavior. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 17, 89–130.

Ferris, G. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (1992). Perceptions of organizational politics. Journal of Management, 18, 93–116.

Firth, R. (1967). Themes in economic anthropology: A general comment. Themes in Economic Anthropology, 6, 1–28.

Greene, M. J. (2014). On the inside looking in: Methodological insights and challenges in conducting qualitative insider research. The Qualitative Report, 19(29), 1–13.

Hair, J. F., Black, B., Babin, B., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2005). Multivariate data analysis. London: Macmillan.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Heald, S. (2017). Climate silence, moral disengagement, and self-efficacy: How Albert Bandura’s theories inform our climate-change predicament. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 59(6), 4–15.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606.

Hornstein, H. A. (1986). Managerial courage: Revitalizing your company without sacrificing your job. New York: Wiley.

Kacmar, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (1991). Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS): Development and construct validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51, 193–205.

Khan, A. N., & Ali, A. (2018). Factors affecting retailer’s adopti on of mobile payment systems: A SEM-neural network modeling approach. Wireless Personal Communications, 103(3), 2529–2551.

Khan, A. N., Ali, A., Khan, N. A., & Jehan, N. (2018). A study of relationship between transformational leadership and task performance : The role of social media and affective organisational commitment. International Journal of Business Information Systems.

Kim, T.-Y., Hon, A. H. Y., & Crant, J. M. (2009). Proactive personality, employee creativity, and newcomer outcomes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24, 93–103.

Ko, S. (2017). The effects of image making education perceived by students in airline service department on their self-efficacy and department loyalty, 116(23), 859–869.

Lahiri, S., Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., & Renn, R. W. (2008). Will the new competitive landscape cause your firm’s decline? It depends on your mindset. Business Horizons, 51(4), 311–320.

Lam, C., Wan, W., & Roussin, C. (2016). Going the extra mile and feeling energized: An enrichment perspective of organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 379–391.

Landells, E. M., & Albrecht, S. L. (2017). The positives and negatives of organizational politics: A qualitative study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(1), 41–58.

Li, J., Wu, L., & Liu, D. (2014). Insiders maintain voice : A psychological safety model of organizational politics. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(3), 853–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-013-9371-7.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave longitudinal examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 71–92.

Lin, S. H., Ma, J., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000098.

Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Pacific. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Mansbridge, J. J. (2018). A deliberative theory of interest representation. In The politics of interests (p. 26). Taylor & Francis Group.

Martin, F., & Tao-Peng, F. (2017). Morality matters? Consumer identification with celebrity endorsers in China. Asian Business & Management, 16(4–5), 272–289.

Masterson, S. S., & Stamper, C. L. (2003). Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee-organization relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 473–490.

May, D. R., Matthew, T. L., & Schwoerer, E. C. (2014). The influence of business ethics education on moral efficacy, moral meaningfulness, and moral courage: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 67–80.

Miller, B. K., Rutherford, M. A., & Kolodinsky, R. W. (2008). Perceptions of organizational politics: A metaanalysis of outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22, 209–222.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1453–1476.

Molm, L. D., Peterson, G., & Takahashi, N. (1999). Power in negotiated and reciprocal exchange. American Sociological Review, 876–890.

Mouzelis, N. (2017). The perils of politics. In Organizational pathology: Life and death of organizations (1st ed., p. 14). New York: Routledge.

Nakano, C. (2007). The significance and limitations of corporate governance from the perspective of business ethics: Towards the creation of an ethical organizational culture. Asian Business & Management, 6(2), 163–178.

Nica, E., Hurjui, I., & Ștefan, I. (2016). The relevance of the organizational environment in workplace bullying processes. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 2, 83–89.

Nunnally, J. C., & Berstein, I. H. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: Mc Graw Hill.

Onyango, G. (2017). Organizational disciplinary actions as socio-political processes in public organizations. Public Organization Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-017-0401-7

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. In Issues in organization and management series. Lexington, MA, England: Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com.

Özduran, A., & Tanova, C. (2017). Manager mindsets and employee organizational citizenship behaviours. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 589–606.

Pereira, V., Malik, A., Froese, F., & Merchant, H. (2015). Impact on human resource management, employment relations practices and organisation behaviour. Special Issue Call for Papers from Journal of Asia Business Studies.

Pfeffer, J. (1992). Managing with power: Politics and influence in organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy. Published November.

Purba, D. E., Oostrom, J. K., Van Molen, H. T., & Born, M. P. (2015). Personality and organizational citizenship behavior in Indonesia: The mediating effect of affective commitment. Asian Business & Management, 14(2), 147–170.

Rosen, C. C., Levy, P. E., & Hall, R. J. (2006). Placing perceptions of politics in the context of the feedback environment, employee attitudes, and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 211–220.

Rousseau, D. (1995). Understanding written and unwritten agreements. In Psychological contracts in organizations. Sage Publications.

Saleem, H. (2015). The impact of leadership styles on job satisfaction and mediating role of perceived organizational politics. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 172(27), 563–569.

Salomonsen, H. H., Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2016). Civil servant involvement in the strategic communication of Central Government Organizations: Mediatization and functional politicization. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 10(3), 207–221.

Schminke, M., Johnson, M., & Rice, D. (2015). Justice and organizational structure: A review. The Oxford Handbook of Justice in the Workplace.

Shao, P., Li, A., & Mawritz, M. (2018). Self-protective reactions to peer abusive supervision: The moderating role of prevention focus and the mediating role of performance instrumentality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(1), 12–25.

Shrestha, A. K., & Mishra, A. K. (2015). Interactive effects of public service motivation and organizational politics on nepali civil service employees’ organizational commitment. Business Perspectives and Research, 3(1), 21–35.

Sousa, M., & van Dierendonck, D. (2017). Servant leaders as underestimators: Theoretical and practical implications. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(2), 270–283.

Stamper, C. L., & Masterson, S. S. (2002). Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 875–894.

Staw, B. M., Sandelands, L. E., & Dutton, J. E. (1981). Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: A multilevel analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 501–524.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Exploring nonlinearity in employee voice: The effects of personal control and organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 1189–1203.

Tong, C., Tak, W. I. W., & Wong, A. (2015). The impact of knowledge sharing on the relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction: The perception of information communication and technology (ICT) practitioners in Hong Kong. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 5(1), 19.

Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Talmud, I. (2010). Organizational politics and job outcomes: The moderating effect of trust and social support. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 2829–2861.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1275–1286.

Wanberg, C. R., & Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 132–142.

Wang, J., & Kim, T. Y. (2013). Proactive socialization behavior in China: The mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of supervisors’ traditionality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(3), 389–406.

Westphal, J. D., & Zajac, E. J. (1997). Defections from the inner circle: Social exchange, reciprocity, and the diffusion of board independence in US corporations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 161–183.

Wu, L., Chuang, C. H., & Hsu, C. H. (2014). Information sharing and collaborative behaviors in enabling supply chain performance: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 141, 122–132.

Xiongfei, C., Khan, A. N., Zaigham, G. H. K., & Khan, N. A. (2018). The stimulators of social media fatigue among students: Role of moral disengagement. Journal of Educational Computing Research.

Zhang, H., Zhou, X., Wang, Y., & Cone, M. H. (2011). Work-to-family enrichment and voice behavior in China: The role of modernity. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 5, 199–218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, N.A., Khan, A.N. & Gul, S. Relationship between perception of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior: testing a moderated mediation model. Asian Bus Manage 18, 122–141 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-018-00057-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-018-00057-9