Abstract

This retrospective cohort study examined the relationship between a cholecystectomy and the subsequent risk of peptic ulcers using a population-based database. Data for this study were retrieved from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005. This study included 5209 patients who had undergone a cholecystectomy for gallstones and 15,627 sex- and age-matched comparison patients. We individually tracked each patient for a 5-year period to identify those who subsequently received a diagnosis of peptic ulcers. We found that of the 20,836 sampled patients, 2033 patients (9.76%) received a diagnosis of peptic ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period: 674 from the study group (12.94% of the patients who underwent a cholecystectomy) and 1359 from the comparison group (8.70% of the comparison patients). The stratified Cox proportional hazard regressions showed that the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for peptic ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period was 1.48 (95% CI = 1.34~1.64) for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy than comparison patients. Furthermore, the adjusted HRs of gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period were 1.70 and 1.71, respectively, for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy compared to comparison patients. This study demonstrated a relationship between a cholecystectomy and a subsequent diagnosis of peptic ulcers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A cholecystectomy is the gold standard treatment for symptomatic gallstones1,2. However, some studies reveal that after a cholecystectomy, about 7~47% of patients are dissatisfied with the procedure; the most common reason for this is related to postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS)1,2,3. Previous studies reported that duodenogastric reflux (DGR) with bile reflux gastritis (BRG) following a cholecystectomy may contribute to some persistence of PCS4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

DGR is a natural physiological phenomenon attributed to the reflux of duodenal contents from the duodenum into to the stomach which presents for a short period and causes few symptoms16,17. However, the pathological DGR is very common in adults after a cholecystectomy4,5,6,7,8,9,17. Previous reports showed that 20~85% of post-cholecystectomy symptomatic patients have pathological DGR within 6 months after a cholecystectomy8,11,12,13,14. Pathological DGR occurs when the reflux of pancreatic and biliary secretions is excessive or lasts for a long time and subsequently damages the gastric mucosa and leads to the development of BRG and peptic ulcers15,18,19,20,21. Furthermore, studies demonstrated that DGR may suppress the somatostatin concentration that is produced by the alkaline nature or pancreatic component of the reflux, which subsequently results in hypersecretion of acid and hypergastrinemia18,22,23,24. DGR may therefore be considered a common factor in the pathogenesis of gastric and duodenal ulcers23,24,25,26.

However, all such studies relied upon regional samples, or on data from a few selected hospitals or subpopulations of patients and as such, do not permit unequivocal conclusions. In addition, according to our knowledge, no study has attempted to investigate the risk of peptic ulcers following a cholecystectomy. Therefore, this retrospective cohort study aimed to examine the relationship between a cholecystectomy and the subsequent risk of peptic ulcers using a population-based database.

Methods

Database

Data for this retrospective cohort study were retrieved from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID2005). The LHID2000, which was created and released by the Taiwan National Health Research Institute (NHRI), includes medical claims of 1,000,000 enrollees. These 1,000,000 enrollees were randomly selected by the Taiwan NHRI from enrollees listed in the 2005 Registry of Beneficiaries (n = 27,378,403) under the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program. The LHID2005 provides an exclusive opportunity for researchers in Taiwan to longitudinally explore the relationship between a cholecystectomy and the risk of peptic ulcers.

This study was exempted from full review by the Institutional Review Board of the National Defense Medical Center because the LHID2005 consists of de-identified secondary data released to the public for research purposes.

Study sample

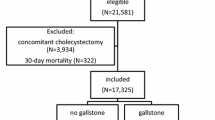

This study was designed to include a study group and a comparison group. We selected the study group by identifying 6834 patients who had undergone a cholecystectomy (International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure codes 51.2, 51.21, 51.22, 51.23 and 51.24) during January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2008. We also assured that all included patients had received a discharge diagnosis of gallstones (ICD-9-CM codes 574.0~574.4 and 574.6~574.9). In Taiwan, all gallstones diagnoses were confirmed using an ultrasound scan. In addition, we excluded 11 patients aged less than 18 years in order to limit the study sample to the adult population. We defined the date of the cholecystectomy as the index date for the study group. Thereafter, we excluded 1614 patients who had ever received a diagnosis of peptic ulcers within 3 years prior to the index date. As a result, the study group included 5209 patients who had undergone a cholecystectomy for gallstones.

Similarly, we retrieved the comparison group from the remaining enrollees in the Registry of Beneficiaries of the LHID2005. We first excluded enrollees who had a history of gallstones or who had undergone a cholecystectomy. However, the LHID2005 did not allow us to identify and exclude patients who had undergone a cholecystectomy prior to 1995 because the NHI program began in 1995. This potential bias would lead the findings of this study toward the null hypothesis. We subsequently used the SAS procsurveyselect program (SAS System for Windows, vers. 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) to randomly select 15,627 subjects (3 for every patient who underwent a cholecystectomy) matched according to sex, age group and the year of the index date. For the comparison group, the year of the index date was simply a matched year during which the patients used healthcare services. We then assigned their first healthcare use occurring in the index year as their index date for the comparison group. Moreover, we ensured that all selected comparison patients did not undergo a cholecystectomy during the 5-year follow-up period. We also assured that none of the selected comparison patients had a history of peptic ulcers within 3 years prior to the index date.

Ultimately, this study included 20,836 sampled patients. We individually tracked each patient for 1, 3 and 5 years starting from the index date to identify those who subsequently received a diagnosis of peptic ulcers (ICD-9-CM codes 531~533) in ambulatory care visits (including outpatient departments of hospitals and clinics) during the follow-up period. In Taiwan, when a gastroenterologist suspects that a patient has a peptic ulcer, he/she may provide the patient with a temporary diagnosis of a peptic ulcer in order to perform the associated clinical examinations, endoscopies or lab tests for confirmation without receiving a monetary penalty from the Bureau of the NHI. The peptic ulcer commonly diagnosed by gastroenterologists based upon characteristic symptoms and endoscopies. If a patient has a confirmed peptic ulcer diagnosis after an examination, the patient will receive routine therapy and have a second peptic ulcer diagnosis in their next outpatient visit. Therefore, in order to increase the validity of the diagnoses of peptic ulcers, we only selected peptic ulcer cases if they received two or more peptic ulcer diagnoses.

Statistical analysis

The SAS system was used for statistical analyses in this study. We used Pearson Chi-squared tests to compare differences in medical comorbidities between patients who underwent a cholecystectomy and comparison patients. These comorbidities included hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401-405), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM codes 272.0-272.4), diabetes (ICD-9-CM codes 250), coronary heart disease (CHD) (ICD-9-CM codes 410-414 or 429.2), obesity (ICD-9-CM codes 278, 278.0, or 278.00-278.01), alcohol abuse/alcohol dependence syndrome (ICD-9-CM codes 303) and tobacco use disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 305.1). We only counted comorbidities if the condition occurred in an inpatient setting or appeared in two or more ambulatory care claims coded before the index date in this study. Furthermore, we used stratified Cox proportional hazard regressions (stratified by age group, sex and the year of the index date) to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for peptic ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period in patients who underwent a cholecystectomy and comparison patients, with cases censored if individuals died during that time (839 [16.1%] from the study cohort and 1755 [12.3%] from the comparison cohort). The significance level was p = 0.05 for this study.

Results

Table 1 presents the distributions of demographic characteristics and medical comorbidities stratified by the presence or absence of a cholecystectomy. After the patients were matched according to sex, age group and the year of the index date, we found that patients who underwent a cholecystectomy were more likely to have the comorbidities of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, CHD, obesity, alcohol abuse/alcohol dependence syndrome and tobacco use disorder (all p < 0.001) than were comparison patients.

Table 2 presents the incidence of peptic ulcers during the follow-up period. Of the 20,836 sampled patients, 2033 patients (9.76%) received a diagnosis of peptic ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period: 674 from the study group (12.94% of the patients who underwent a cholecystectomy) and 1359 from the comparison group (8.70% of comparison patients) (p < 0.001).

Table 2 also presents the crude and adjusted HRs for peptic ulcers. The stratified Cox proportional hazard regressions (stratified by age group, sex and the year of the index date) showed that the HRs for peptic ulcers during the 1-, 3- and 5-year follow-up periods were 2.34 (95% CI = 1.98~2.77), 1.84 (95% CI = 1.63~2.06) and 1.56 (95% CI = 1.41~1.72), respectively, for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy compared to comparison patients. Furthermore, the HR of peptic ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period was 1.48 (95% CI: 1.34~1.64) for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy after censoring individuals who died during the follow-up period and adjusting for the patients’ geographic location, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, CHD, obesity, alcohol abuse/alcohol dependence syndrome and tobacco use disorder.

Table 3 presents the crude and adjusted HRs for gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers. We found that the adjusted HRs of gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period were 1.70 (95% CI: 1.44~1.99) and 1.71 (95% CI: 1.36~2.15), respectively, for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy compared to comparison patients. Patients who underwent a cholecystectomy had an increased risk of peptic ulcers regardless of the type of peptic ulcer.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study found that 12.94% of the patients who underwent a cholecystectomy had peptic ulcers during 5-year follow-up period compared to 8.70% of patients who did not undergo a cholecystectomy. The Cox proportional hazard regression analysis suggested that a cholecystectomy was significantly associated with an increased risk of subsequent peptic ulcers (adjusted HR = 1.48). In addition, the adjusted HRs of gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers during the 5-year follow-up period were 1.70 and 1.71, respectively, for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy compared to comparison patients.

The current findings on the incidence rates of peptic ulcers were parallel to those of prior studies, all of which reported that 3.0~10% of patients develop peptic ulcers following a cholecystectomy15,27,28,29. The mechanisms underlying the relationship between a cholecystectomy and peptic ulcers remain unclear. One possible explanation could be that DRG, which damages the gastric mucosa by bile acids and pancreatic phospholipase A2, leads to peptic ulcers20,21. In addition, some animal studies demonstrated that DGR suppresses somatostatin concentrations and increases intragastric gastrin and acid secretion18,22,23,24,25,26. Therefore, DGR may be considered a factor in the pathogenesis of gastric and duodenal ulcers as suggested by some researchers18,30,31. Furthermore, previous studies indicated that antroduodenal motility is altered and gastric emptying is delayed after a cholecystectomy, which may also play a possible role in the etiology of gastric ulcers32,33.

In addition to gastric acid and chemical injury by bile acids related to peptic ulcers, Helicobacter pylori is considered to play the most important role in peptic ulcers nowadays34,35. Recent studies suggested that H. pylori infection is one possible cause of gallstones30,31,36. The synergistic effect of a high reflux bile acid load and H. pylori infection is likely to be a critical event in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcers37,38.

The present study showed that the HRs for peptic ulcers during the 1-, 3- and 5-year follow-up periods decreased with time and were 2.34, 1.84 and 1.56, respectively, for patients who underwent a cholecystectomy compared to comparison patients. Previous studies suggested that the healing and regeneration of the gastric mucosa against repeated bile damage from chronic DRG could result in chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia39,40. Wilson et al. also reported that prolonged DRG in patients of longer than 3 years after a cholecystectomy caused the gastric pH to exceed 3 an increased percentage of the time and was associated with a high incidence of chronic gastritis9. Therefore, according to morphological and physiological changes of the gastric mucosa with chronic excess DRG, the incidence of peptic ulcers could decrease with time due to atrophic gastric mucosa with hypochlorhydria.

This study has several strengths. First, a population-based dataset with a large sample size was used to explore the relationship between a cholecystectomy and peptic ulcers. The large sample size afforded a considerable statistical advantage in detecting actual differences between the study group and comparison group. Second, the diagnosis of peptic ulcers by certified gastroenterologists has a very high validity since it is diagnosed by panendoscopy in Taiwan. In addition, this study only included peptic ulcer cases if they had received two or more peptic ulcer diagnoses.

Nevertheless, the results of this study need to be seen in the light of several limitations. First, the LHID 2005 provides no information on the histology or existence of H. pylori in gastric biopsies. In addition, this database has no relevant records on data for laboratory examination, biochemical examination, or diagnostic imaging and so it was not possible to differentiate between indications for cholecystectomy (biliary colic, cholecystitis or pancreatitis). Second, physicians do not routinely biopsy the gastric mucosa to identify BRG in Taiwan. This may prevent researchers from identifying the pathogenesis of cholecystitis and ERG. Third, although we took important comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes and alcohol abuse) into consideration in the analysis, it is still possible that patients who underwent a cholecystectomy might possess higher risks of peptic ulcers due to undetectable factors in our claims dataset (e.g., a genetic tendency, poor lifestyle, or other illnesses). Finally, there may have been a surveillance bias in that patients who underwent a cholecystectomy were more likely to have frequent outpatient clinic visits, which may have led to early detection of peptic ulcers.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study demonstrated a relationship between a cholecystectomy and a subsequent diagnosis of peptic ulcers. In patients who underwent a cholecystectomy, peptic ulcers contribute to some symptoms of PCS. We suggest that clinicians be alert and suspect peptic ulcers with persistent epigastric pain or dyspepsia in patients with a prior cholecystectomy. In addition, future studies need to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning the relationship detected in this study.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tsai, M.-C. et al. Increased Risk of Peptic Ulcers Following a Cholecystectomy for Gallstones. Sci. Rep. 6, 30702; doi: 10.1038/srep30702 (2016).

References

Ros, E. & Zambon, D. Post-cholecystectomy symptoms: a prospective study of gallstone patients before and two years after surgery. Gut. 28, 1500–1504 (1987).

Vander Velpen, G. C., Shimi, S. M. & Cuschiere, A. Outcome after cholecystectomy for symptomatic gall stone disease and effect of surgical access: laparoscopic v open approach. Gut. 34, 1448–1451 (1993).

Weinert, C. R., Arnett, D., Jacobs, D. Jr. & Kane, R. L. Relationship between persistence of abdominal symptoms and successful outcome after cholecystectomy. Arch Intern Med. 160, 989–995 (2000).

Kalima, T. & Sjöberg, J. Bile reflux after cholecystectomy. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 67, 153–156 (1981).

Buxbaum, K. L. Bile gastritis occurring after cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 77, 305–311 (1982).

Nath, B. J. & Warshaw, A. L. Alkaline reflux gastritis and esophagitis. Annu Rev Med. 35, 383–396 (1984).

Eriksson, L., Forsgren, L., Nordlander, S., Mesko, L. & Sandstedt, B. Bile reflux to the stomach and gastritis before and after cholecystectomy. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 520, 45–51 (1984).

Lorusso, D. et al. Duodenogastric reflux, histology and cell proliferation of the gastric mucosa before and six months after cholecystectomy. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 58, 43–50 (1995).

Wilson, P. et al. Pathologic duodenogastric reflux associated with persistence of symptoms after cholecystectomy. Surgery. 117, 421–428 (1995).

Svensson, J. O., Gelin, J. & Svanvik, J. Gallstones, cholecystectomy and duodenogastric reflux of bile acid. Scand J Gastroenterol. 21, 181–187 (1986).

Nudo, R., Pasta, V., Monti, M., Vergine, M. & Picardi, N. Correlation between post-cholecystectomy syndrome and biliary reflux gastritis. Endoscopic study. Ann Ital Chir. 60, 291–300 (1989).

Abdel-Wahab, M. et al. Does cholecystectomy affect antral mucosa? Endoscopic, histopathologic and DNA flow cytometric study. Hepatogastroenterology. 47, 621–625 (2000).

Gad Elhak, N. et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori, gastric myoelectrical activity, gastric mucosal changes and dyspeptic symptoms before and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 51, 485–490 (2004).

Shrestha, M. L., Khakurel, M. & Sayami, G. Post cholecystectomy biliary gastritis and H. pylori infection. J Institute Med. 27 (2005).

Abu Farsakh, N. A., Stietieh, M. & Abu Farsakh, F. A. The postcholecystectomy syndrome. A role for duodenogastric reflux. J Clin Gastroenterol. 22, 197–201 (1996).

Fein, M., Fuchs, K. H., Bohrer, T., Freys, S. M. & Thiede, A. Fiberoptic technique for 24-hour bile reflux monitoring. Standards and normal values for gastric monitoring. Dig Dis Sci. 41, 216–225 (1996).

Mason, R. J. & De Meester, T. R. Importance of duodenogastric reflux in the surgical outpatient practice. Hepato Gastroenterol 46, 48–53 (1999).

Kaminishi, M. et al. A new model for production of chronic gastric ulcer by duodenogastric reflux in rats. Gastroenterology. 92, 1913–1918 (1987).

Zhang, Y. et al. Histological features of the gastric mucosa in children with primary bile reflux gastritis. World J Surg Oncol. 10, 27 (2012).

Boyle, J. M., Neiderhiser, D. H. & Dworken, H. J. Duodenogastric reflux in patients with gastric ulcer disease. J Lab Clin Med. 103, 14–21 (1984).

Eyre-Brook, I. A. et al. Relative contribution of bile and pancreatic juice duodenogastric reflux in gastric ulcer disease and cholelithiasis. Br J Surg. 74, 721–725 (1987).

Thomas, W. E. Inhibitory effect of somatostatin on gastric acid secretion and serum gastrin in dogs with and without duodenogastric reflux. Gut. 21, 996–1001 (1980).

Peters, M. N., Feldman, M., Walsh, J. H. & Richardson, C. T. Effect of gastric alkalinization on serum gastrin concentrations in humans. Gastroenterology. 85, 35–39 (1983).

Niemelä, S. Duodenogastric reflux in patients with upper abdominal complaints or gastric ulcer with particular reference to reflux-associated gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 115, 1–56 (1985).

Thomas, W. E., Ardill, J. & Buchanan, K. D. Suppression of somatostatin release by duodenogastric reflux in dogs. Gut. 25, 1230–1233 (1984).

Tzaneva, M. Effects of duodenogastric reflux on gastrin cells, somatostatin cells and serotonin cells in human antral gastric mucosa. Pathol Res Pract. 6, 431–438 (2004).

Peterli, R. et al. Postcholecystectomy complaints one year after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Results of a prospective study of 253 patients. Chirurg. 69, 55–60 (1998).

Vere, C. C. et al. Endoscopical and histological features in bile reflux gastritis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 46, 269–274 (2005).

Sanjay, P. et al. A 5-year analysis of readmissions following elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy - cohort study. Int J Surg. 9, 52–54 (2011).

Chen, W., Li, D., Cannan, R. J. & Stubbs, R. S. Common presence of Helicobacter DNA in the gallbladder of patients with gallstone diseases and controls. Dig Liver Dis. 35, 237–243 (2003).

Abayli, B. et al. Helicobacter pylori in the etiology of cholesterol gallstones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 39, 134–137 (2005).

Rovelstad, R. A. The incompetent pyloric sphincter. Bile and mucosal ulceration. Am J Dig Dis. 21, 165–173 (1976).

Nogi, K. et al. Duodenogastric reflux following cholecystectomy in the dog: role of antroduodenal motor function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 15, 1233–1238 (2001).

Peterson, W. L. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 324, 1043–1048 (1991).

Kuipers, E. J., Thijs, J. C. & Festen, H. P. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 9, 59–69 (1995).

Attaallah, W. et al. Gallstones and Concomitant Gastric Helicobacter pylori Infection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 643109 (2013).

Zullo, A. et al. Gastric pathology in cholecystectomy patients: role of Helicobacter pylori and bile reflux. Clin Gastroenterol. 27, 335–338 (1998).

Graham, D. Y. & Osato, M. S. H. pylori in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer: interaction between duodenal acid load, bile and H. pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 95, 87–91 (2000).

Sobala, G. M. et al. Bile reflux and intestinal metaplasia in gastric mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 46, 235–240 (1993).

Sipponen, P., Kekki, M., Seppälä, K. & Siurala, M. The relationships between chronic gastritis and gastric acid secretion. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 10, 103–118 (1996).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.-T.K. and M.-C.T. participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. H.-C.L. and L.-T.K. performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. C.-Z.L. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, MC., Huang, CC., Kao, LT. et al. Increased Risk of Peptic Ulcers Following a Cholecystectomy for Gallstones. Sci Rep 6, 30702 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30702

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30702

- Springer Nature Limited