Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus; GAS) is a widespread human pathogen and causes streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS). STSS isolates have been previously shown to have high frequency mutations in the csrS/csrR (covS/covR) and/or rgg (ropB) genes, which are negative regulators of virulence. However, these mutations were found at somewhat low frequencies in emm1-genotyped isolates, the most prevalent STSS genotype. In this study, we sought to detect causal mutations of enhanced virulence in emm1 isolates lacking mutation(s) in the csrS/csrR and rgg genes. Three mutations associated with elevated virulence were found in the sic (a virulence gene) promoter, the csrR promoter and the rocA gene (a csrR positive regulator). In vivo contribution of the sic promoter and rocA mutations to pathogenicity and lethality was confirmed in a GAS mouse model. Frequency of the sic promoter mutation was significantly higher in STSS emm1 isolates than in non-invasive STSS isolates; the rocA gene mutation frequency was not significantly different among STSS and non-STSS isolates. STSS emm1 isolates possessed a high frequency mutation in the sic promoter. Thus, this mutation may play a role in the dynamics of virulence and STSS pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is one of the most common human pathogens and causes various infections, ranging from uncomplicated pharyngitis and skin infections to severe and even life-threatening manifestations, such as necrotizing fasciitis (NF) and bacteremia1. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) is a severe invasive infection recently characterized by the sudden onset of shock and multi-organ failure and has a high mortality rate, ranging from 30% to 70%2.

STSS isolates were previously shown in a study to have high frequency mutations in the GAS two component regulatory system genes, csrS (covS) and csrR (covR), and/or the rgg gene, all of which are negative regulators of virulence. STSS isolates with these mutations elevated the expression of various virulence genes and were associated with in vitro escape from host defenses and in vivo lethality, as seen using a mouse STSS model. These mutations were thus regarded as responsible factors for STSS3. In this study of clinical STSS isolates, the frequency of these mutations in emm-genotyped isolates, excluding the prevalent emm1 genotype, was 71.4% (65/91 isolates), whereas that of the emm1-genotyped isolates was 39.7% (29/73). Additionally, 44 emm1 STSS isolates did not have any mutations in these genes3. Thus, these mutations were significantly found in emm genotypes other than emm1 (p = 0.000045 by Χ2 analysis). Therefore, we hypothesized that there are other mutation(s) in these 44 emm1-genotyped STSS isolates responsible for enhanced virulence. In this study, we examined this hypothesis by identifying the STSS emm1 isolates that significantly elevated the expression of important virulence genes such as scpA, sic, sda1, nga and ska as compared to non-invasive or non-STSS isolates to detect the novel mutations underpinning this enhanced virulence and demonstrate pathogenicity of these mutations in a GAS mouse model. Such insights will shed light on the mechanisms underlying pathogenicity in STSS emm1-genotyped isolates.

Results

Selection of emm1 STSS isolates with significantly elevated expression of key virulence genes

For our study, we conducted quantitative RT-PCR from 44 emm1 STSS isolates lacking mutations in the csrS, csrR and rgg genes and 3 emm1 non-invasive isolates (negative controls) to assess the expression of five virulence genes, scpA, sic, sda1, nga and ska, known to be elevated in invasive strains4. We selected isolates with expression levels >10-fold in at least one virulence gene as compared to controls (Table 1). Ten isolates met this criterion, with four showing elevated expression in all five genes and six with elevation only in the sic gene. We then systematically set out to identify the mutations responsible for enhanced expression of these virulence genes.

Promoter mutation of csrR/csrS operon

We sequenced the promoter regions of csrR/csrS and rgg genes. In the emm1 STSS NIH342 and NIH344 isolates, a 1-bp deletion in the csrR/csrS promoter was observed when compared to the csrR/csrS promoter of the non-STSS Se235 isolate (aaac to aac) (Fig. 1a). This deletion was positioned between the −35 and −10 elements of the promoter as determined in Gusa & Scott (2005)5 and shortened the spacer length between the −35 and −10 elements from 17 bp to 16 bp (Fig. 1a). We hypothesized that this deletion inhibited expression of the csrR/csrS promoter, thus resulting in enhanced virulence. To measure the transcriptional level of the csrR gene, we introduced the csrR-phoZF transcriptional fusion plasmid either with the deletion (pABGcsr(16spacer); as derived from NIH344) or without the deletion (pABGcsr(17spacer); as derived from Se235) into NIH344 and Se235 isolates and measured alkaline phosphatase activity. Additionally, we introduced pABG0 plasmids into these isolates. Isolates harboring pABGcsr(16spacer) had lower promoter activity than isolates harboring pABGcsr(17spacer) (Fig. 1b). Thus, the 1-bp deletion in the csrR/csrS promoter of STSS emm1 isolates NIH342 and NIH344 resulted in decreased expression of csrR/csrS genes.

The sequence of csrR promoter and csrR promoter activity.

(a) csrR promoter sequence in which 1 bp was deleted in the promoter region of NIH342 and NIH344 STSS isolates, particularly in the putative −10 and −35 regions (underlined). Number next to N indicates the length of spacer between −10 and −35 DNA elements. Box indicates the csrR/covR gene. (b) Transcriptional level of the csrR gene in a non-invasive isolate (Se235) and a STSS isolate with the 1-bp deletion in the promoter region (NIH344). To measure the transcriptional levels of csrR genes, we used csrR-phoZF transcriptional fusion plasmids to assess alkaline phosphatase activity. Mean activity ± SD of each strain is shown for three independent experiments. Error bars show the standard deviation (SD).

Promoter mutation of sic gene

Six emm1 STSS isolates (NIH135, NIH150, NIH185, NIH270, NIH392 and NIH436) only elevated the expression of the sic gene, a virulence gene encoding the extracellular streptococcal inhibitor of complement (Table 1). We hypothesized this was due to a mutation in the sic promoter and thus sequenced the region. We found a 6-bp insertion (aaaata) in all six isolates (Fig. 2a). We discerned this insertion’s effect on sic transcription via alkaline phosphatase reporter assays. We either introduced the sic-phoZF transcriptional fusion plasmid pABGsic(270), containing the sic promoter derived from NIH270, or the pABGsic(Se) plasmid, containing the sic promoter derived from Se235, into NIH270 and Se235 isolates, respectively (Table 2) and measured alkaline phosphatase activity. Strains harboring pABGsic(270) and thus the insertion, exhibited higher activity than strains harboring pABGsic(Se), which lacked the insertion (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the increase of sic expression is due to this 6-bp insertion found in the six emm1 STSS isolates.

The sequence of sic promoter and sic promoter activity.

(a) Sic promoter sequence. A 6-bp (aaaata) sequence was inserted in STSS isolates (such as NIH270) near the start codon (next to atgaat). The start codon (atg) is indicated by the upper line. Box indicates the sic gene. (b) Transcriptional level of the sic gene in each strain, Se235 and NIH270. To measure the transcriptional levels of sic genes, we used sic-phoZF transcriptional fusion plasmids and assessed alkaline phosphatase activity. Mean activity ± SD of each strain is shown for three independent experiments. Error bars show SD.

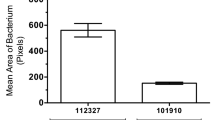

Mutations of the rocA and scaR regulator genes

In the remaining two isolates, NIH324 and NIH388, the expression of all five virulence genes increased. We hypothesized that this was due to mutations in genes involved in regulation. Thus, we sequenced regulator genes in the two isolates and the non-STSS isolate Se235. Particularly, we sequenced 152 genes annotated as involved in regulation in the S. pyogenes MGAS5005 genome sequence (GenBank accession number CP000017). To note, the 152 regulator genes sequenced in Se235 were used as reference sequences. Compared to Se235, NIH388 was mutated in the spy0367 (scaR) gene and NIH324 was mutated in the spy1318 (rocA) gene (Fig. 3a). Each intact gene derived from Se235 was inserted in pLZ12-Km to perform complementation tests. The increase of mRNA abundance of all five virulence genes in NIH324 was complemented and thus reduced to levels similar to Se235, upon introduction of pLZrocA, which contained the rocA gene (Fig. 3b,c and data not shown). The increase of virulence gene expression in NIH388 was not complemented upon introduction of pLZscaR, which contained the scaR gene (data not shown). These results showed that enhanced virulence gene expression in NIH324 was due to a mutation in rocA. With regard to NIH388, increased virulence was not due to mutations in either gene. Two kinds of NIH388 strains were clinically isolated, one which formed mucoid colonies and the other non-mucoid colonies. The mucoid colony strain up regulated the expression of all virulence genes (Table 1), while the non-mucoid colony strain had comparable expression levels of virulence genes as Se235. We sequenced and compared the whole genomes of these two NIH388 strains. Although 11 putative SNPs were observed, these were not the causative agents of the two strains’ differential regulation of virulence (data not shown).

Mutation position of rocA and the transcriptional level of the nga and the sda1 virulence genes by the rocA mutant.

(a) The rocA gene sequence. A 1-bp (t) sequence was deleted in STSS isolate. Box indicates the rocA gene. The expression of the (b) nga and the (c) sda1 virulence genes in Se235, NIH324 and NIH324 replaced with an intact rocA gene was analyzed by RT-PCR. Columns represent the relative mRNA expression levels of each gene from each strain. The expression level of Se235/pLZ12 strain is shown as 1. Values are represented as means ± SD (n = 4). Error bars show SD.

Mutation of the sic promoter or the rocA gene is important in STSS pathogenesis of mice

In the 10 STSS emm1 isolates, we found mutations in the sic promoter, the csrR promoter, or the rocA gene that conferred increased virulence gene expression. It is well-established that virulence is enhanced upon inhibition of csrS/csrR gene expression6. To elucidate the role of the sic promoter or rocA in STSS infection in vivo, we injected Se235 isolates with either the rocA or sic promoter mutation or Se235 alone in GAS model mice and compared the lethality between the two groups. The mutant strains showed significantly higher lethality than the Se235 strain (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4). This result suggested that sic promoter-mutated and rocA-mutated emm1 strains isolated from STSS patients are more virulent than strains isolated from patients with non-invasive infections.

Mutation of rocA gene and sic promoter enhances the lethality of GAS mouse model.

Survival curves of mice infected with either rocA (Se235rocA) or sic promoter (Se235sicP*) mutant strains or non-STSS Se235 strain. Mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with 4 × 107 CFU of each GAS strain and survival was observed for eight days post-infection. Mortality differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05) between Se235 and Se235sicP* and between Se235 and Se235rocA, as determined by a log-rank test. Survival curves were generated from three independent experiments using a total of 12 ddY mice for each strain.

Mutation frequency of the rocA gene and the sic promoter in STSS isolates

In this study, we showed that mutations in the rocA gene and the sic promoter of emm1 clinical isolates from STSS patients caused lethality in mice, suggesting these mutations play important roles in the STSS pathogenesis. To evaluate the frequency of these in other emm-genotyped isolates, we sequenced the rocA gene and the sic promoter in STSS clinical isolates from sterile sites (164 isolates) and non-invasive clinical isolates from non-sterile sites (59 isolates)3.

SIC and DRS (distantly related to SIC) are related proteins present in only four (emm1, emm12, emm55 and emm57) of the >200 GAS emm types7. We sequenced upstream regions of sic and drs in 103 emm1 (73 STSS isolates, including six from this study and 30 non-invasive isolates) and 12 emm12 isolates (10 STSS isolates and 2 non-invasive isolates). There were no emm55 and emm57 isolates. In emm1 isolates, a total of 10 STSS isolates (13.7%) had the sic promoter insertion mutation, which was not in any of the emm1 non-invasive isolates. The position of mutation and the insertion sequence in the sic promoter were the same in all the mutated isolates. STSS emm1 isolates had a sic promoter mutation at a significantly higher frequency than non-invasive isolates (p = 0.0329; Χ2 analysis). In emm12 isolates, no mutations were observed in the putative drs promoter region. These results highlighted that the sic promoter mutation is unique to STSS emm1 isolates. We sequenced the rocA gene in various emm-genotyped isolates in STSS isolates (164 isolates) and non-invasive isolates (59 isolates). A total of 30 STSS (18.3%) and 15 non-invasive (25.4%) isolates were mutated in the rocA gene. The position of this mutation was the same as previously described8,9. There was no significant difference in the mutation frequency between STSS isolates and non-invasive isolates (p = 0.242 by Χ2 analysis). Collectively, these results suggested that the sic promoter insertion mutations cause STSS rather than the rocA mutation.

In this study, 62.2% of the STSS isolates had mutations in the csrS/R, rgg, and/or sic promoter, whereas isolates from patients with non-invasive disease had significantly fewer mutations in these genes (1.7%) (Fig. 5).

Mutation frequency in the csr, rgg and sic promoters.

The mutation frequency of csr, rgg and sic promoter among S. pyogenes isolates from STSS (164 isolates) and non-invasive infections (59 isolates). STSS isolates (62.2%) had one or mutations in the csrS/R, rgg, and/or sic promoter, whereas isolates from patients with non-invasive disease had significantly fewer mutations in these genes (1.7%). +indicated that all the genes were intact. The number in box indicated the number of isolates in each mutant. The number of STSS and non-invasive isolates in each emm genotype described below: emm1 (STSS 73 isolates, non-invasive 30 isolates); emm3 (26, 15); emm4 (3, 2); emm6 (1, 1); emm11 (3, 2); emm12 (10, 2); emm18 (1, 0); emm22 (7, 1); emm28 (7, 2); emm49 (5, 3); emm53 (1, 0), emm58 (2, 1); emm59 (1, 0); emm60 (1, 0); emm77 (1, 0); emm78 (1, 0); emm81 (4, 0); emm87 (4, 0); emm89 (10, 0); emm91 (1, 0); emm112 (1, 0); emm113 (1, 0).

Discussion

In this study, we found new mutations in the sic promoter, the csrR promoter, or the rocA gene in STSS emm1 isolates. We showed that the sic promoter and rocA mutations increased the expression of virulence gene(s) and enhanced lethality in the mouse model. Mutation of the sic promoter was found at a significantly higher frequency in STSS isolates than in the non-invasive isolates, whereas mutation of rocA did not show the same patter.

In our previous study, the frequency of mutations in the csrS/R and/or rgg genes in emm isolates other than emm1 was 71.4%, whereas the frequency in emm1 isolates was 39.7% (29/73); 44 isolates did not have mutation in these genes at all3. Specifically in this study, 62.2% of the STSS isolates had mutations in the csrS/R, rgg, and/or sic promoter, whereas isolates from patients with non-invasive disease had significantly fewer mutations in these genes (1.7%) (Fig. 5). Additionally, 50.7% (37/73) of emm1 STSS isolates had mutations in the csrS/csrR, rgg, and/or the sic promoter. However, mutation frequency was still significantly lower in emm1 STSS isolates than in the other emm genotypes (p = 0.0065 by Χ2 analysis). It is possible that additional mechanisms cause the upregulation of virulence genes in emm1 STSS isolates.

STSS isolates had a significantly higher frequency of the sic promoter mutation than did non-invasive isolates. We showed that this mutant was important in the pathogenesis of invasive infection in the GAS mouse model. In our previous study, we found mutations in negative regulators that led to overproduction of a number of virulence factors3. The mutation in the sic promoter is different in that only one protein (the virulence factor SIC) was probably overexpressed and this mutation led to the overexpression of SIC, implicating it as a crucial factor to STSS pathogenesis in vivo. Particularly, SIC protein is a secreted protein that interferes with complement and antibacterial proteins/peptides10,11,12; it is found in only two GAS emm genotypes, emm1 and emm5710,13. About 50% of STSS is caused by emm1 GAS in Japan14. Thus, we speculate that emm1 isolates with this mutation are poised to be extremely virulent due to overexpression of this unique factor. The consensus sequence (ATTARA) for CsrR15 is found next to the sic promoter 6-bp insertion mutation. However, as the consensus sequence is not disrupted by the insertion, we do not know if CsrR binding was affected. Perez et al.16 reported 42 small regulatory RNAs in emm1 isolates. The small RNA, SR1681917, is positioned in the upstream region of the sic gene16 and this small RNA may regulate sic gene expression. The sic gene may also be regulated by other small RNAs17. Structural changes in the RNA binding site of sic may have occurred due to the 6-bp insertion and the small RNAs would not be able to bind, perhaps leading to upregulation of sic.

When the length of the spacer between the −35 and −10 elements of the csrR promoter was decreased from 17 bp to 16 bp, expression of the csrR/csrS operon also decreased. Recently, Rosinski-Chupin et al.18 reported on the consensus sequence of the sigma 70-dependent promoter in S. agalactiae. In this study, 17 bp was the most common spacer length between the −10 and −35 DNA elements. It is also well established that promoters with a 17-bp spacer yield higher levels of transcription than otherwise identical promoters with 16-bp spacers19,20,21. These studies further corroborate our findings that decrease of csrR gene transcription observed in emm1 isolates was due to shorter spacer length.

The frequency of mutation in the rocA gene was not significant between STSS and non-invasive isolates. Lynskey et al.8 and Miller et al.9 reported that the RocA protein in emm18 and emm3 isolates is truncated and leads to the enhanced expression of virulence factors. In this study, RocA in an emm18 isolate and many emm3 isolates were truncated at the same position in both STSS isolates and non-invasive isolates. RocA in an emm11 isolate and an emm81 isolate was also truncated at the same position. While rocA mutations in emm1 isolates may not have been significantly observed at a higher frequency in STSS vs. non-STSS isolates, such mutations may be important in establishing virulent clones in other emm genotypes, like emm18 and emm3.

In conclusion, we have identified novel mutations that increased virulence gene(s) expression in STSS emm1 isolates, specifically the sic promoter or the rocA gene. These mutations caused lethality in mice and the significantly higher frequency of the sic promoter mutation in STSS emm1 isolates implicates this mutation of utmost importance in the landscape of STSS onset and pathogenesis.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study complies with the guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki. This study protocol was approved by the institutional individual ethics committees for the use of human subjects (the National Institute of Infectious Diseases Ethic Review Board for Human Subjects) and the animal experiments (the National Institute of Infectious Diseases Animal Experiments Committee). Written informed consent was obtained from study participants. All clinical samples were stripped of personal identifiers not necessary for this study. All animal experiments were performed according to the Guide for animal experiments performed at National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan.

Plasmids, bacterial strains and culture conditions

The plasmids used in this study are described in Table 2. STSS criteria were based on those proposed by the Working Group on Severe Streptococcal Infections22. The clinical isolates from STSS and non-invasive (non-STSS) infections were collected during 1973–2008 as previously reported3. Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a host for plasmid construction and was grown in liquid of Luria-Bertani medium with shaking or on agar plates at 37 °C. GAS was cultured in Todd-Hewitt broth (Becton Dickinson, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (THY media) without agitation or on Columbia Agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson). Cultures were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2. When required, antibiotics were added to the medium at the following final concentrations: kanamycin (Km), 25 μg/mL for E. coli and 200 μg/mL for GAS; spectinomycin (Sp), 25 μg/mL for E. coli and GAS. The growth of GAS was turbidimetrically monitored at 600 nm using MiniPhoto 518R (Taitec, Tokyo, Japan).

DNA sequencing

Nucleotide sequences were determined using automated sequencers, such as the Applied Biosystems 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan).

Animals

Male 5–6-week-old outbred ddY mice were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) condition. All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Ethics Review Committee of Animal Experiments of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan.

Construction of the sic-phoZF transcriptional fusion plasmid

To construct plasmids that could measure sic transcriptional levels, we used the pABG5 plasmid23 that has the phoZF reporter gene. When expressed, this reporter gene will produce alkaline phosphatase that is secreted from cells and can easily be measured. In the engineering of this construct, we deleted the promoter region of the phoZF gene but not the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) region of pABG5, resulting in pABG0. We amplified the sic promoter region of STSS and non-STSS isolates via PCR using the primers: sic-up1 (5′-GGGGATCCATTAGCGAAACAAGCTGAAG-3′) and sic-up4 (5′-GGGAATTCCAGTCATCTCCAGACCAGTC-3′). PCR products were digested with BamH1 and EcoR1 in order to clone into the BamHI-EcoRI site upstream of the phoZF SD region of pABG0, resulting in the fusion plasmids pABGsic(Se) and pABGsic(270).

Construction of the csrR-phoZF transcriptional fusion plasmid

In order to engineer fusion plasmids capable of measuring csrR promoter activity, we amplified the csrR promoter region of STSS and non-STSS isolates by PCR with the primers: covP1-Bm (5′-GGGGATCCCTTGCAAGGGTTGTTTGATG-3′) and covPR3-Ec (5′-GGGAATTCCAAGAGAAACGAATCTAGCC-3′). PCR products were digested with BamH1 and EcoR1 in order to clone into the BamHI-EcoRI site upstream of pABG0, resulting in the fusion plasmids pABGcsr(17spacer) and pABGcsr(16spacer).

Construction of scaR and rocA complementation plasmids

To map potential mutations in the scaR and rocA transcriptional regulator genes found in STSS isolates, these genes were amplified via PCR from the non-STSS isolate Se235. The scaR gene was amplified from Se235 using the primers: scaRF-Bm (5′-GGGGATCCCTTTCCCATCATTTCTCTCC-3′) and scaRR-Ec (5′-GGGAATTCAAGTCAAAGGCTTAAAAATGG-3′). The rocA gene was amplified from Se235 using the primers: rocAop1 (5′-GGGCCATGGGAAGGAGAAGGATAAATGTTAG-3′) and rocA6-Ec (5′-GGGAATTCGGGACTATTGTCTCAGACTC-3′). The resulting PCR products were inserted into pLZ12-Km24, yielding pLZscaR and pLZrocA, respectively.

Construction of deletion or insertion mutants

Construction of the rocA mutant

To create a rocA deletion mutant, four DNA fragments were amplified via PCR. A DNA fragment containing the 5′ end of rocA and the adjacent upstream chromosomal DNA was amplified from the NIH324 STSS emm1 isolate using the primers: rocA-del1 (5′-TCGACGTCCGGATCCGGGAAGGTCAAGTCTGTGCGGG-3′) and rocA-del2 (5′-ACGAAAATCAAGCTTGAGAAGGAGAAGGATAAATG-3′). A fragment containing the 3′ end of rocA and the adjacent downstream chromosomal DNA was amplified from the NIH324 using the primers: rocA-del3 (5′-AATGGTGGAAACACTCAAAATCAACTTAAGAGTC-3′) and rocA-del4 (5′-GCCTTTTTTACGCGTCTTAACATCATTAGCAACACC-3′). A DNA fragment containing pFW12 (pFW12-PCR) was amplified using the primers: pFW12-PCR1 (5′-GGATCCGGACGTCGACGGCCGTA-3′) and pFW12-PCR2 (5′-ACGCGTAAAAAAGGCCCACAAAAGTGGG-3′). A DNA fragment containing aad9, spectinomycin resistant gene, (spc-PCR) was amplified from the pFW1225 using the primers: spc3 (5′-AAGCTTGATTTTCGTTCGTG-3′) and spc4 (5′-AGTGTTTCCACCATTTTTTC-3′). These four PCR products were circularized using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions, in order to create the plasmid pFWrocA. This plasmid was then introduced into Se235 by electroporation and transformants were selected on Columbia Agar plate supplemented with 5% sheep blood containing spectinomysin. The replacement of the native rocA gene by the rocA-deleted mutant allele was verified by PCR and the resultant strain was named Se235rocA.

Construction of the sic promoter disruption mutant

To construct sic promoter disruption mutants, two DNA fragments were amplified via PCR. A DNA fragment containing the upstream region of the sic promoter was amplified from the NIH270 emm1 STSS isolate chromosomal DNA using the primers: sicP-ins1 (5′-TCGACGTCCGGATCCGTTAGAAACGATTACTAGAG-3′) and sicP-ins2 (5′-ACGAAAATCAAGCTTCAGTATTACAAAGTGATAG-3′); a fragment containing the sic promoter and the adjacent downstream chromosomal DNA was amplified from NIH270 was amplified using the primers: sicP-ins3 (5′-AATGGTGGAAACACTCTGAGTGAACATCAAGAGAG-3′) and sicP-ins4 (5′-GCCTTTTTTACGCGTCGTCTGACCAGCCACCATAC-3′). These two respective PCR products, pFW12-PCR and spc-PCR, were circularized using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit in order to create the plasmid pFWsicP*. This plasmid was then introduced into the non-STSS strain Se235 by electroporation and transformants were selected as described above. The replacement of the native sic promoter gene by the sic promoter disruption mutant was verified by PCR and sequencing and the resultant strain was named Se235sicP*.

phoZF alkaline phosphatase activity assay

The reporter gene phoZF used in this study encodes a chimeric protein consisting of both the N-terminal domain of protein F and the C-terminal domain of Enterococcus faecalis alkaline phosphatase (phoZ). PhoZF is secreted from the cell and detected in the supernatant. Alkaline phosphatase activity was measured as previously described26.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

To examine the expression of virulence genes in emm1-genotyped isolates, total RNA was extracted from 44 emm1-genotyped STSS isolates and 3 emm1-genotyped non-invasive isolates (negative controls) and we performed quantitative RT-PCR to assess the transcriptional abundance of five virulence genes, scpA, sic, sda1, nga and ska, known to be elevated in invasive strains4. Briefly, GAS was grown to late-log phase (OD600 = 0.8–1.0) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and total RNA was extracted from bacterial cells using the RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA synthesis was performed with the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time) (Takara Bio), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcript levels were determined using the ABI PRISM Sequence Detection System 7000 (Applied BioSystems) and Premix Ex Taq (Perfect Real Time) (Takara Bio). For real-time amplification, the template was equivalent to 5 ng of total RNA. Measurements were performed in triplicate; a reverse-transcription-negative blank of each sample and a no-template blank served as negative controls. gyrA was used as an internal control. Primers and probes were described Supplementary Table 1.

Complete-genome comparisons

The whole genome of STSS emm1 strain NIH388 was sequenced by paired-end sequencing on an Illumina Hiseq2000 sequencing system (Cosmo-Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and comparison was performed by a data mining service (Filgen Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan). The reference genome sequence used was S. pyogenes 476 (GenBank accession No. AP012491).

GAS infection in a mouse model

A total of 4 × 107 CFU of GAS suspended in 0.5 mL PBS was injected intraperitoneally into five- to six-week-old ddY outbred male mice (12 mice/GAS strain). The number of mice that survived was compared statistically using the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ikebe, T. et al. Spontaneous mutations in Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from streptococcal toxic shock syndrome patients play roles in virulence. Sci. Rep. 6, 28761; doi: 10.1038/srep28761 (2016).

References

Cunningham, M. W. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13, 470–511 (2000).

Bisno, A. L. & Stevens, D. L. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 240–245 (1996).

Ikebe, T. et al. Highly frequent mutations in negative regulators of multiple virulence genes in group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome isolates. PLos Pathog. 6, e1000832 (2010).

Sumby, P., Whitney, A. R., Graviss, E. A., DeLeo, F. R. & Musser, J. M. Genome-wide analysis of group a streptococci reveals a mutation that modulates global phenotype and disease specificity. PLos Pathog. 2, e5 (2006).

Gusa, A. A. & Scott, J. R. The CovR response regulator of group A streptococcus (GAS) acts directly to repress its own promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1195–1207 (2005).

Cole, J. N., Barnett, T. C., Nizet, V. & Walker, M. J. Molecular insight into invasive group A streptococcal disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 724–736 (2011).

Hartas, J. & Sriprakash, K. S. Streptococcus pyogenes strains containing emm12 and emm55 possess a novel gene coding for distantly related SIC protein. Microbial. Pathog. 26, 25–33 (1999).

Lynskey, N. N. et al. RocA Truncation Underpins Hyper-Encapsulation, Carriage Longevity and Transmissibility of Serotype M18 Group A Streptococci. PLos Pathog. 9, e1003842 (2013).

Miller, E. W. et al. Regulatory rewiring confers serotype-specific hyper-virulence in the human pathogen group A Streptococcus. Mol. Microbiol. 98, 473–489 (2015).

Akesson, P., Sjöholm, A. G. & Björck, L. Protein SIC, a novel extracellular protein of Streptococcus pyogenes interfering with complement function. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1081–1088 (1996).

Fernie-King, B. A., Seilly, D. J., Davies, A. & Lachmann, P. J. Streptococcal inhibitor of complement inhibits two additional components of the mucosal innate immune system: secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor and lysozyme. Infect. Immun. 70, 4908–4916 (2002).

Frick, I. M., Akesson, P., Rasmussen, M., Schmidtchen, A. & Björck, L. SIC, a secreted protein of Streptococcus pyogenes that inactivates antibacterial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16561–16566 (2003).

Binks, M., McMillan, D. & Sriprakash, K. S. Genomic location and variation of the gene for CRS, a complement binding protein in the M57 strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 71, 6701–6706 (2003).

Ikebe, T. et al. Increased prevalence of group A streptococcus isolates in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome cases in Japan from 2010–2012. Epidemiol. Infect. 143, 864–872 (2015).

Federle, M. J. & Scott, J. R. Identification of binding sites for the group A streptococcal global regulator CovR. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1161–1172 (2002).

Perez, N. et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Small Regulatory RNAs in the Human Pathogen Group A Streptococcus. PLos ONE 4, e7668 (2009).

Mangold, M. et al. Synthesis of group A streptococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1515–1527 (2004).

Rosinski-Chupin, I. et al. Single nucleotide resolution RNA-seq uncovers new regulatory mechanisms in the opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus agalactiae. BMC Genomics 16, 419 (2015).

Aoyama, T. et al. Essential structure of E. coli promoter: effect of spacer length between the two consensus sequences on promoter function. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 5855–5864 (1983).

Mulligan, M. E., Brosius, J. & McClure, W. R. Characterization in vitro of the effect of spacer length on the activity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase at the TAC promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3529–3538 (1985).

Stefano, J. E. & Gralla, J. D. Spacer mutations in the lac ps promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 1069–1072 (1982).

The Working Group on Severe Streptococcal Infections. Defining the group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: rationale and consensus definition. JAMA 269, 390–391 (1993).

Alexander, B., Parsonage, G. D., Ross, R. P. & Caparon, M. G. The RofA binding site in Streptococcus pyogenes is utilized in multiple transcriptional pathways. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1529–1540 (2000).

Hanski, E., Horwitz, P. A. & Caparon, M. G. Expression of protein F, the fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes JRS4, in heterologous streptococcal and enterococcal strains promotes their adherence to respiratory epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 60, 5119–5125 (1992).

Podbielski, A., Spellerberg, B., Woischnik, M., Pohl, B. & Lutticken, R. Novel series of plasmid vectors for gene inactivation and expression analysis in group A streptococci (GAS). Gene 177, 137–147 (1996).

Ikebe, T., Endoh, M. & Watanabe, H. Increased expression of the ska gene in emm49-genotyped Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated from patients with severe invasive streptococcal infections. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 58, 272–275 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Working Group for Beta-hemolytic Streptococci in Japan and all microbiologists and clinicians who have contributed to the study. We thank Dr. Podbielski for the gift of the plasmid pFW12 and Dr. Caparon for the gift of the plasmids pABG5 and pLZ12-Km. This work was partly supported by a grant (H22-Shinkou-Ippan-013 to T.I.) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (25460554 to T.I.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I., T.M., M.A. and M.O. conceived and designed the experiments. T.I., T.M., H.N., H.O., R.O., C.M., R.K., M.K., M.S., N.S., M.A. and M.O. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. T.I., T.M., M.A. and M.O. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. T.I., T.M., H.N., H.O., R.O., C.M., R.K., M.K., M.S., N.S., M.A. and M.O. participated in discussions of the research and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ikebe, T., Matsumura, T., Nihonmatsu, H. et al. Spontaneous mutations in Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from streptococcal toxic shock syndrome patients play roles in virulence. Sci Rep 6, 28761 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28761

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28761

- Springer Nature Limited