Abstract

A working alliance (WA) is a multidimensional construct signifying a collaborative relationship between a client and a therapist. Systematic reviews of therapies to treat depression and anxiety, almost exclusively in adults, show WA is essential across psychotherapies. However, there are critical gaps in our understanding of the importance of WA in low-intensity therapies for young people with depression and anxiety. Here, we describe an initiative to explore the effect of WA on anxiety and depression outcomes in youth aged 14–24 years through a scoping review and stakeholders’ consultations (N = 32). We analysed 27 studies; most were done in high-income countries and evaluated one-on-one in-person therapies (18/27). The review shows that optimal WA is associated with improvements in: relationships, self-esteem, positive coping strategies, optimism, treatment adherence, and emotional regulation. Young people with lived experience expressed that: a favourable therapy environment, regular meetings, collaborative goal setting and confidentiality were vital in forming and maintaining a functional WA. For a clinician, setting boundaries, maintaining confidentiality, excellent communication skills, being non-judgmental, and empathy were considered essential for facilitating a functional WA. Overall, a functional WA was recognised as an active ingredient in psychotherapies targeting anxiety and depression in young people aged 14–24. Although more research is needed to understand WA’s influence in managing anxiety and depression in young people, we recommend routine evaluation of WA. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to identify strategies that promote WA in psychotherapies to optimise the treatment of anxiety and depression in young people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A working alliance, also referred to as a therapeutic alliance, is a multidimensional construct signifying a collaborative relationship between a client and a therapist1,2,3. A functional Working Alliance (WA) hinges on shared confidence that therapy will be helpful. Also, there is concurrence between the client and therapist over the assignment of therapy tasks; the relationship includes mutual trust and reciprocal liking1,4. Collectively, a functional WA has three salient elements, i.e., the creation of a bond between the patient and therapist, agreement in setting therapy goals and guiding scheduled tasks necessary for attaining therapy objectives (goal setting)1,2,3.

Systematic reviews of therapies to treat depression and anxiety, almost exclusively done in adults, demonstrate that WA is essential across psychotherapies1,2,3,4,5,6,7. A functional WA, as perceived by both client and therapist, predicts greater uptake of interventions, client engagement, adherence to treatment, and symptom reduction1,5,7. Conversely, ruptured and/or low WA reduces the effectiveness of known-efficacious treatments2,4. Of the available reviews on young people (YP), Sun et al. (2019), looking at cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for internalising disorders in YP, found that goal setting, parental involvement, relapse prevention, and booster sessions explained only 14% of the variance predicting treatment outcomes6. This implies that other factors, potentially including WA, explain treatment effects. Another meta-analysis in youth demonstrated that a strong WA is predictive of positive treatment outcomes in family-involved treatment for youth problems4. However, there are critical gaps in our understanding of the importance of WA in individual psychotherapies and low-intensity therapies (e.g., behavioural activation, psychoeducation, and problem-solving therapy) for YP with depression and anxiety. Also, there is inconclusive evidence regarding the putative mechanism through which WA optimises treatment outcomes1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Consequently, Welcome Trust has launched Active Ingredients commissions to understand elements essential for the prevention, ongoing treatment and management, and prevention of relapse of anxiety and depression in youth aged 14–24 years8.

The Active Ingredients commission seeks to understand the putative mechanisms by which treatments bring about clinical changes, including understanding the context and possible harms8. For instance, some teams have demonstrated the usefulness of interventions such as self-compassion, physical activity, emotional regulation, and problem-solving therapy (PST) in managing anxiety and depression in youth9,10. Regardless of intervention effectiveness, potential active ingredients such as WA are essential for optimal outcomes1,2,3,4,5,6,7. For instance, despite PST being effective in managing depression in youth11, a poor WA would invariably lead to poor clinical outcomes1,2,3,4,5,6,7.

Since most mental health problems (75%) initially occur in youth12, it is vital that WA is understood in order to maximise the effectiveness of prevention interventions, treatment and ongoing management of anxiety and depression in youth11. Understanding the role of WA could also refine the implementation of known effective treatments. More importantly, there have not been previous attempts to appraise evidence on WA in youth with key input from youth with lived experience of anxiety and/or depression. Here, we describe an initiative to explore the effect of WA on anxiety and depression outcomes in youth aged 14–24 years through a scoping review and stakeholders’ consultations.

Methods

This initiative involved a series of successive, complimentary activities (scoping review, stakeholder consultations and validation workshops), described in detail subsequently. First, we conducted a scoping review, followed by stakeholders’ interviews and went on to summarise and synthesise the findings collaboratively with YP through validation workshops.

Scoping review

We undertook a scoping review to appraise the evidence of the impact of WA on depression and anxiety in young people aged 14–24 years. The following research questions guided the scoping review:

-

1.

Does better WA improve clinical outcomes of interventions for young persons (14–24 years) with anxiety and depression?

-

2.

What WA elements (bond, goal, and task) influence treatment outcomes?

-

3.

What factors (e.g. patient characteristics, therapy format and delivery mode, etc.) influence the WA-outcome relationship?

-

4.

Can ruptured/dysfunctional working alliances have negative/harmful effects on the clients and or treatment outcomes?

The review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR checklist13 (see Supplementary File 1).

Eligibility criteria

The following criteria was applied in selecting articles:

-

a.

Study designs/interventions: we included all quantitative designs (randomised controlled trials, cross-sectional, cohort and case-control studies). Systematic reviews, editorials, qualitative studies, case studies and study protocols were excluded.

-

b.

Participants/settings: we analysed all studies reporting on WA in young persons with anxiety and/or depression aged 14–24 years across all settings. In cases where the participants’ average age was beyond 24 years, we only included the study if ≥50% of participants were in the 14–24 age range.

-

c.

Language: we only analysed articles published in the English language; our preliminary searches did not yield/reveal articles published in languages other than English.

Information sources

Peer-reviewed articles were searched/retrieved from these electronic databases; PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, PsychINFO and Africa-Wide information. Databases were searched from inception through August 2021. Where only an abstract was available online, an attempt to contact the lead author was made, requesting the full article to ensure literature saturation. The article was excluded from the review if there was no response in two weeks following three email reminders. We also reviewed grey literature using the Google Scholar search engine to search potential databases such as university databases and conference proceedings, among others, for articles. For completeness, we also performed both backward and forward searches of the reference lists of identified articles and databases, respectively.

Search strategy

As an illustration, articles in CINAHL were searched using the following Boolean logic operators: (“working alliance” OR “therapeutic alliance” OR “collaborative alliance” AND “anxiety OR depression OR anxiety/depression OR (anxiety AND depression)” AND “young people OR young adults OR teenagers OR Adolescent*“.

Selection of sources of evidence

First, three early career researchers and three young people with lived experience of anxiety and/or depression piloted the data collection tool by extracting data from five (5) articles. Two researchers then independently searched articles using a pre-defined search strategy (see above). The principal author (JMD) then imported the searches into Mendeley Software and removed duplicates. Afterwards, another set of independent researchers screened the articles by title and abstract. JMD then performed backwards and forward citation searches to identify other potential articles. More senior researchers reviewed the list of identified articles to check for the completeness of the searches.

Data charting process

Once searches were finalised, two researchers retrieved the full articles and extracted the data. Two researchers independently cross-examined all extracted data, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with a more experienced researcher who made the final verdict.

Data items

The data extraction sheet included information/variables such as author, year, age group, primary and secondary outcome measures, and critical findings. WA, anxiety, and depression were the primary outcomes for this scoping review. Secondary outcomes included variables such as changes in relationships, and coping mechanisms, amongst other relevant outcomes.

Synthesis of results

Results were qualitatively synthesised per study objectives. Study outcomes were summarised per study design.

Key stakeholder consultations

Using semi-structured interviews, we consulted various stakeholders to explore further issues identified through the scoping review. Sampling was purposive to ensure informed discussions and a range of perspectives. Stakeholders therefore comprised: lay health counsellors (n = 6), psychologists (n = 2), occupational therapists (n = 2), psychiatrists (n = 2), and YP with lived experiences (n = 20). Discussions explored various issues, including WA elements considered most important by both YP with anxiety and/or depression and therapists. We also explored the therapist and YP patient characteristics (e.g., age, gender) that influence the therapeutic alliance-outcome relationship. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 coincided with the commencement of data collection activities, which necessitated a shift from in-person to phone interviewing. Discussions were informed by a guide (see Supplementary Files 2 and 3), and text data from the interviews were entered in real-time into hard copy templates. Where possible, verbatim quotes were included. Initially, first-level coding was done by reading the interviews and identifying key emerging issues. The next step involved identifying patterns and linkages within the established codes and collating the codes into thematic areas using thematic analysis14.

Data synthesis/validation workshops

We convened an initial workshop to triangulate/synthesise findings from the scoping review and stakeholder consultations. We summarised the scoping review and stakeholders’ findings in a simplified manner; YP representatives reviewed this to ensure simplicity and relevance. The validation workshops followed a modified “theory of change” approach to map the “pathway to impact”. Using visuals and placards, we co-created a visual graphic model summarising participants’ views and data interpretation. The output of this initial workshop was the visual first iteration of the mechanistic framework hypothesising pathways by which WA influences treatment outcomes. Subsequently, YP representatives independently consulted with the community advisory group (CAG), constituting YP with lived experiences, the appropriateness of the hypothesised model. Finally, we convened a second workshop to finalise the insight analysis collaboratively with YP.

Involvement of young persons (YP)

We worked collaboratively with young people with lived experience of anxiety and/or depression, and their specific roles included:

-

I.

Project design: e.g., developing a unified definition of WA, identification/mapping of key stakeholders.

-

II.

Literature searches: YP representatives previously trained and involved in systematic reviews assisted with the pre-application screening of available reviews and assisted with article screening for the actual scoping review.

-

III.

Data collection: e.g., co-facilitating stakeholders’ interviews.

-

IV.

Analysis and synthesis: e.g., reviewing themes emerging from stakeholders’ interviews.

-

V.

Dissemination: e.g., co-developing output animation.

Results

Scoping review

Study selection

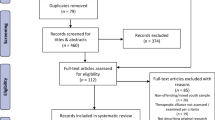

Initially, 274 articles were identified by searching academic databases and grey literature. After filtering duplicates and screening by title and abstract, 70 full articles were retrieved. Further screening was applied, and 27 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (see Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Nearly all studies (26/27) were conducted in high-income countries (HICs), mainly in the US (12/27). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was the most used diagnostic tool (10/27). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was the most commonly applied treatment modality (16/27), and most sessions were done individually (18/27) as opposed to in a group format (5/27). Only two (2) studies utilised digital therapy platforms, with the remainder being in-person therapies (25/27) (Table 1).

Working alliance measurement and association with key clinical outcomes

Table 2 outlines the assessment timing, assessor, key findings, and overall synthesis per study. The working alliance inventory was the most applied outcome measure (12/27). WA was mainly measured at the beginning (14/27) or at both the beginning and end of therapy (17/27). Most assessments were completed by clients (15/27), with therapists’ ratings only recorded in two studies. A functional WA was recognised as an active ingredient in psychotherapies targeting anxiety and depression in young persons aged 14–24 years. Most studies (24/27) revealed a positive association between WA and clinical outcomes. Two studies revealed a null association, with a single study showing a negative association.

Stakeholders’ consultations

Young persons experiencing anxiety and depression views

Consultations with young people indicated what was necessary for developing a WA. A conducive environment, regular engagements, and confidentiality were vital for developing the client-therapist bond. Involvement in setting treatment goals was essential in forming a WA. One respondent said, “…if two people can agree on the goals and outcomes of the entire session and what they will be working on, l think it will help develop a better connection and bond.” There was an agreement between the young people with lived experience that involvement in coming up with tasks influenced WA formation, which subsequently affected treatment outcomes. Young people valued being involved in the planning of therapy tasks. Client characteristics such as willingness to engage in therapy, politeness, and being expressive were essential for developing a WA. A trustworthy therapist with good communication skills was considered ideal for developing a WA. Also, cultural background, inappropriate dressing, therapists’ age, gender, and religion were potential barriers to developing working alliances. Patients much-preferred therapists of the same gender. A female client stated, “…my counsellor was female, and it helped me a lot.” Also, respondents preferred more experienced counsellors and therapists and those of similar religious orientations (see Table 3).

Clinicians’ views on working alliance

The conceptualisation of working/therapeutic alliance aligned with the working definition. However, some lay counsellors were unsure of the term’s meaning. After further probing using descriptors and examples, the lay counsellors could relate to the concept. Most clinicians viewed personal connection with a client as an essential aspect of improving treatment outcomes that facilitates understanding between the client and clinician, builds trust, facilitates empathy, and enables the application of good listening skills. Setting boundaries, maintaining confidentiality, and being non-judgmental and empathetic were considered pre-requisite clinician attributes for forming a WA. Also, goal setting was deemed integral to successful therapy. Furthermore, the importance of participants’ motivation levels, mutual agreement on goals, and the number of times the goals were set and reviewed were considered crucial for forming and maintaining a WA (see Table 4).

Synthesis of scoping review and stakeholders’ consultations

Figure 2 identifies potential mechanisms by which WA can optimise treatment outcomes for anxiety and depression in young people. Bonding between a client and therapist and consensus on therapy goals and tasks are fundamental in developing a WA. Certain conditions, including therapists’ characteristics (e.g., communication skills, empathy), less severe baseline symptoms, initial symptoms change, and regular engagement between the therapist and client, are essential for developing an optimal WA. Once created, a WA can lead to increased adherence to treatment, improved self-esteem, increased treatment satisfaction, and improved relationships and coping skills. Ultimately, WA is associated with increased treatment effectiveness, thus mitigating the burden of anxiety and depression in young persons. WA can potentially optimise treatment outcomes across psychotherapies and treatment formats, i.e., individual vs group therapy and in both physical and digital treatment formats.

Discussion

Triangulating findings from the scoping review, stakeholder consultations and synthesis workshops, we conclude that WA is an essential active ingredient in psychotherapies addressing anxiety and depression in young persons. Overall, a greater WA is associated with improvements in depression and anxiety in young people. Our scoping review findings are consistent with what has been observed in reviews focusing exclusively on adults1,2,5,15.

Despite the universal agreement on the importance of a functional WA, the exact mechanism by which a WA optimises reductions in anxiety and depression remains largely obscure3. From literature1,2,5,16,17,18 and our stakeholders’ consultations, it appears that improvements in the WA are associated with improvements in interpersonal relationships, self-esteem, positive coping strategies, optimism, adherence to treatment protocols, and emotional regulation. Improvements in negative psychosocial indices and treatment processes/factors attenuate anxiety and depression symptoms. Consequently, improved mental health can positively influence WA creating a positive feedback loop1,2,5. However, some studies included in the scoping review did not find an association between WA and depression or anxiety2.

Recent research into psychotherapy with adults has attempted to use advanced statistical modelling techniques to understand the WA-clinical outcome relationship1. However, heterogeneity in methodologies makes it difficult to conceptualise and model the association between WA and anxiety or depression1,2,5. For instance, in a systematic review by Baier et al. (2020), most studies retrieved demonstrated that WA is a mediator of change. However, reverse causality and mediation by a third confounding variable could not be ruled out1,5. Despite the inconsistencies in the literature, it is, thus, vital to explore the most salient element associated with improved WA.

In the scoping review, improvements in bond and tasks were associated with improvements in interpersonal functioning19,20. Common mental disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression) are sometimes associated with relationship problems; therefore, establishing a bond with the therapists can affect the client’s social life21. It is generally suggested that early WA is essential in the early stages of the therapeutic process. Early bonding between the client-therapist is likely to improve the client’s agreement on the task and subsequent adherence to treatment procedures, ultimately improving treatment outcomes1.

The bond formation and task completion depend on patient and therapist characteristics. However, despite forming a WA during sessions, if clients are not provided with coping skills, the mediation of WA in symptomatic relief is attenuated2,15. Therapists corroborated this proposition during our stakeholders’ consultations. Elsewhere, in a naturalistic study, Webb et al. (2014) demonstrated that the task component was statistically associated with treatment outcomes after controlling for temporal confounders (patient expectations and prior symptom change)22. The same study demonstrated the importance of agreement on concrete tasks as being fundamental to changes in depression in CBT22. The importance of task completion is further supported by Zelenchich et al.23, who explored the effect of WA on anxiety and depression in youth with acquired brain injury. Facilitation by the therapists in completing tasks was linked to improved functioning and lower anxiety and depression23. This is further supported by a systematic review of adult patients undergoing CBT for anxiety disorders; task agreement was more predictive of the WA therapeutic-outcome association, with bond/goals-outcome association equivocal2.

We also set out to explore factors “mediators” to the WA-outcome association. Understanding these factors is essential to fostering a functional WA. The following variables can potentially affect the WA-outcome association: client and therapist characteristics, therapist professional experience, the timing of WA formation, therapy type(s), therapy delivery mode, therapy format ((digital/physical and individual/group), and setting (inpatient/outpatient). These are discussed in the subsequent paragraphs.

Pre-treatment patient characteristics, including motivation, hope for change, and expectancy in therapy effectiveness, are precursors to forming a functional WA19. For instance, patient optimism towards the potential for improved symptoms is linked to better WA and more favourable treatment outcomes. Consequently, therapists must build realistic expectations and optimism that therapy will be effective2,22,24. Also, patients with good attachment histories, adaptive attachment styles and developed social skills are more likely to forge good relationships with therapists, thus improving WA7. More critically, positive relations, characterised by an ability to develop a stronger bond between a patient and a therapist, are essential. It creates trust and safety, which spills over to the agreement of goals and subsequent completion of agreed tasks2.

Conversely, other patient characteristics (e.g. attachment styles, diagnosis) are potentially detrimental to the WA-outcome relationship2,21,25,26. Some studies suggest that a functional WA does not seem to optimise treatment in patients with personality disorders and relationship problems21,25. Patients with relationship problems may have challenges connecting with the therapist, which may cause a poor WA, and subsequent poor treatment outcomes26. Also, clients with greater relationship difficulties are likely to be more dependent on their therapist; this may lead to challenges in developing their problem-solving capabilities, in turn influencing the ability to forge a functional WA and treatment outcomes19,26. Inversely, the greater reliance on the therapist may cause an improved alliance, specifically the client and therapist bond2. Furthermore, patients with fewer relationship difficulties may be more realistic in treatment outcomes as they appreciate the difficulty in attaining meaningful change19.

Overall, there seems to be no consensus regarding the salient patient characteristics influencing the WA-outcome association. Some studies have concluded that a functional WA does not seem to play a huge role in treatment success; instead, other non-specific factors (e.g. adherence, symptoms severity) seem to influence treatment effectiveness19. Therefore, additional research is needed to explore contexts where WA can be harmful or circumstances under which a functional WA can deter patients’ functional recovery. Optimising WA is essential as ruptures in WA can lead to decreased treatment expectancy, which may negatively affect adherence, thus ultimately reducing treatment effectiveness. However, the evidence concerning this is limited, and more research is needed for definitive conclusions2.

Our stakeholder consultations identified empathy from the therapist as an essential element across patients. Young people described how providers’ courteous treatment increased their confidence in the treatment process. In Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), enhancing a client’s ability to agree on tasks and assignments, including eliciting emotional engagement during therapy, is essential for forging a functional WA. However, evidence from a systematic review exploring the active ingredients of CBT in adult anxiety disorders produced mixed results2. Studies are needed to better understand critical windows for good WA to impact therapy outcomes and any moderating effects on the empathy-outcome association2. The exploration is essential given that a De Re et al. (2012) meta-analysis demonstrated that therapists’ characteristics hugely contribute to the WA formation regardless of patient diagnosis, research design, and WA measurement7. For instance, the therapist’s professional experience seemingly predicts WA cultivation.

From the studies gleaned from the scoping review22,27,28 and our consultations, it appears that greater professional experience is associated with better treatment outcomes and greater WA. This is inconsistent with outcomes from a study by Goldstein et al.29. exploring the comparability of anxiety/depression symptoms change, skills acquisition and WA between experienced and student therapists. In their study, WA was superior for clients treated by students than qualified therapists. Also, a study showed that videoconferencing was equally effective in treating anxiety and depression; a doctoral trainee psychologist was the therapist30. Both alliance and skill acquisition were moderately correlated with therapeutic gains in changes in depression scores30. However, our stakeholders’ consultations were indeterminant; clients revealed that age was a potential determinant for establishing WA, with young people preferring to be treated by a similarly aged lay counsellor. A similar-age counsellor was deemed likely to have the same experiences and relate more to a young person experiencing anxiety and depression. Other clients preferred to be seen by a more mature counsellor who could have more experience addressing the issues at hand. In problem-solving therapy and CBT, more experience appears helpful when the patient is still opening up; an experienced counsellor can use their clinical expertise to facilitate problem-solving in the client15,22,27,28.

Evidence is inconclusive regarding the requisite timing of WA on changes in mental health functioning15. For example, some studies in the scoping review suggested that a more favourable early WA is associated with more significant symptom improvement3,5,15,17,19,22,25,31,32,33,34, with others reporting a null association2,16. The discrepancies have been attributed to differences in outcome measures, the timing of WA assessment and methodological differences, i.e., sample sizes, heterogeneity in study participants, and study designs, amongst other methodological issues2,4,5,22,34.

A meta-analysis exploring the WA therapeutic-outcome relationship in CBT for adults with depression revealed that early WA-outcome correlations are marginally lower than mid-and late assessments5, thus the need for an early establishment of a WA to optimise treatment outcomes5. Another meta-analysis also identified a reciprocal relationship between WA and symptom reduction early in therapy3. Early WA was predictive of post-treatment outcomes and optimised drop rates; this association was evident irrespective of baseline symptom severity and was optimised by greater levels of patients’ engagement with treatment and treatment acceptance in the early stages of therapy3. However, few long-term studies have assessed the temporal WA therapeutic-outcome association.

WA has been mainly studied using cross-sectional or clinical trials with short follow-ups5,16. Hersoug et al. (2013)19 explored the long-term effects of WA on 100 patients three years after receiving dynamic psychotherapy for anxiety, depression and personality disorders. This study showed that a functional WA was predictive of long-term changes in mental health outcomes. Furthermore, higher treatment expectations, less severe symptoms, and the ability to create mutually fulfilling relationships with others were predictive of a better functional WA19. Of note, the temporal relationship between WA and treatment outcomes is not without controversy4,22,34.

A functional WA is considered active across psychotherapies5,34,35. Tschschke et al.28. demonstrated that WA was essential in predicting clinical outcomes for behavioural, cognitive-behavioural, person-centred, and psychodynamic therapies. This proposition is further supported by systematic reviews and meta-analyses exploring the effects of WA on depression and anxiety for CBT1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Most studies analysed in the scoping review primarily focused on the relationship between WA and treatment outcomes for standalone psychotherapies. For example, Stunk et al. (2012) explored the relationship between WA, adherence and symptom change in 176 randomised clients receiving combined cognitive therapy and antidepressants for depression in the US21. A positive WA was associated with symptom change early in therapy. Furthermore, only the task sub-scale was associated with symptom change. However, multivariate analyses showed that only the task subscale remained the statistically significant predictor after controlling for therapist skill and adherence to cognitive therapy. Taken together, the study showed the importance of agreeing on goals and homework provision to influence both WA and subsequent symptomatic changes in combined therapy21. Given the importance of WA across psychotherapies, it is essential to explore the context, i.e. delivery mode, format and settings that influence the WA-outcome association.

In the scoping review, the association between WA and anxiety/depression was the same across delivery modes, i.e., physical vs online therapy and individual vs group therapy16,35. Evidence of the WA across physical formats is unequivocal in suggesting that a functional WA optimises in-person therapy outcomes, with evidence across digital platforms still evolving1,2,4,5,6. A pilot randomised controlled trial (N = 26) showed that videoconferencing clinically equalled in-person CBT, with client satisfaction and client- and therapist-rated WA comparable across the two groups30. Andersson et al.35 explored the association between WA and treatment outcomes in guided CBT in patients with anxiety, depression, generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder (N = 174). The study showed high WA scores comparable to face-to-face therapies. They argued that a WA can still be formed in guided digital self-help despite a lack of physical contact over online interactions; agreeing on goals and homework/tasks is essential for successful therapy outcomes35. Unlike physical sessions, WA in guided digital therapy is a function of the client’s interaction with the therapist online and access to self-help materials/systems35. However, despite the clients improving clinically, there was no association between WA and clinical outcomes; the null association requires further research35. Methodological limitations of this study, including a one-off measurement of WA and using an instrument developed for face-to-face therapies, could account for the null association, or maybe WA may not be an active ingredient for guided self-help modalities.

Most of the WA therapeutic-outcome association knowledge is derived from one-to-one therapy delivery. We also set out to understand the effect of WA on group therapy in young people experiencing anxiety and depression. Scoping review evidence produced mixed findings. Group therapy was associated with increased self-esteem, which had a moderating effect on both WA and depression36. Group interactions and a secure WA were associated with improved self-esteem and reduced depression36. Furthermore, clients with more impaired relational experiences seem to benefit much more from group therapy, signifying a warm WA’s potential impact on treatment outcomes36.

Group therapy among adults with mental health problems is also associated with an increase in WA in psychomotor therapies (body awareness and physical activity), with increases in collaboration as the most salient predictor of changes in WA37. However, a study by McEvoy et al. (2014) exploring the relationship between interpersonal problems, WA, and outcomes following group (n = 115) and individual therapy (n = 84), produced slightly different outcomes26. In this study, compared to group therapy, individual therapy recipients reported greater WA pre-and post-treatment; the differences were statistically significant26. Furthermore, in group therapy, severe pre-treatment anxiety/depression and interpersonal problems were associated with poorer WA and dropout than individual therapy26. Some argue that when compared to individual therapy, the group therapy format may not be the most “conducive” platform for clients with severe pre-treatment interpersonal problems to form a functional WA, given their assumed difficulties in relating to other group members and the therapist(s)2,26. Clinicians echoed this sentiment during our consultations; nevertheless, more studies are needed to understand the effects of group therapy on WA.

Our review also explored the effect of treatment settings (inpatient vs outpatient) on WA. McLeod and Weisz27 carried out a study to explore the relationship between WA and treatment outcomes in youth ((mean age; 10.3 (SD 6.2) years)) with anxiety and depression in an outpatient setting. Their study showed that better child–therapist alliance and parent–therapist alliance during treatment predicted greater reductions in internalising (anxiety and depression) symptoms at the end of treatment. Given that children rarely volunteer to engage in therapy, with parents usually deciding to get involved, a functional WA between therapist(s) and both parents and children is necessary for optimising treatment outcomes27. Using a naturalistic study design, Webb et al. (2014) also explored the association between WA and changes in symptomatology in an inpatient setting. For patients with anxiety and depression (N = 103) receiving combined CBT and antidepressants in a psychiatry facility22, a functional WA was associated with decreased depression. Also, patients with optimism (greater treatment expectations) were likely to form greater WA, subsequently improving treatment outcomes22. It seems reasonable to conclude that the WA-outcome association is independent of the setting in which treatment is provided. Further studies are needed to understand the relationship between setting/context and WA-outcome.

The study’s strengths include using a systematic process in searching, retrieving, analysing and synthesising data across sources. More importantly, this study was primarily driven by persons with lived experiences. The involvement of young persons in planning, collecting, analysing, and synthesising the outcomes increases the review’s relevance to the target population of young persons experiencing anxiety and depression.

However, although our review suggests the positive impact of strong WA in treating depression and anxiety, the generalisation of our findings may be limited. Firstly, we did not formally assess the risk of bias in each study. The scoping review aimed to summarise the relationship between WA and mental health outcomes in young people aged 14–24. Future systematic reviews and meta-analyses are warranted. Secondly, most studies were from high-income countries, and their applicability across different settings could be limited; we only retrieved a solitary study from Kenya, a low-income country34. There is a need for context-specific studies to explore the effect of WA on anxiety and depression, given the potential influence of culture on WA3. We, however, attempted to do so through stakeholder consultations. Thirdly, very few retrieved studies were exclusively done in young adults in the 14–24 age group, which may potentially limit external validity. Finally, albeit the heterogeneous measurement in the WA2, there is a need for psychometric evaluation studies to standardise WA measures from diverse perspectives, i.e., patient-, observer- and therapist perspectives6.

In conclusion, this review indicates that WA is a salient active ingredient across psychotherapies in managing ongoing anxiety and depression in young persons aged 14–24. Findings from stakeholder consultations and synthesis workshops corroborated this. Although more research is needed to understand WA’s influence in managing anxiety and depression in young people, based on this review and subsequent stakeholder consultations, we recommend routine evaluation of WA from both patients’ and clients’ viewpoints2,7,37 at multiple timepoints over therapy. Also, there is a need to explore ways to promote better WA across psychotherapies2,7. Lastly, more targeted research using: longitudinal designs, adequately powered experimental designs, multiple WA measurements and advanced statistical modelling techniques to differentiate within- and between-patient differences1,2,6 is needed to understand the impact of WA on anxiety and depression in young persons aged 14–24 years.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baier, A. L., Kline, A. C. & Feeny, N. C. Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: a systematic review and evaluation of research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 82, 101921 (2020).

Luong, H. K., Drummond, S. P. A. & Norton, P. J. Elements of the therapeutic relationship in CBT for anxiety disorders: a systematic review. J. Anxiety Disord. 76, 102322 (2020).

Flückiger, C. et al. The reciprocal relationship between alliance and early treatment symptoms: a two-stage individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 88, 829–843 (2020).

Welmers-van de Poll, M. J. et al. Alliance and treatment outcome in family-involved treatment for youth problems: a three-level meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 21, 146–170 (2018).

Cameron, S. K., Rodgers, J. & Dagnan, D. The relationship between the therapeutic alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with depression: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 25, 446–456 (2018).

Sun, M., Rith-Najarian, L. R., Williamson, T. J. & Chorpita, B. F. Treatment features associated with youth cognitive behavioral therapy follow-up effects for internalizing disorders: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 48, S269–S283 (2019).

Del, Re. A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D. & Wampold, B. E. Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance-outcome relationship: a restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 642–649 (2012).

Sebastian, C. L., Pote, I. & Wolpert, M. Searching for active ingredients to combat youth anxiety and depression. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1266–1268 (2021).

Egan, S. J. et al. A review of self-compassion as an active ingredient in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression in young people. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 49, 385–403 (2022).

Krause, K. R. et al. Problem-solving training as an active ingredient of treatment for youth depression: a scoping review and exploratory meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 21, 1–14 (2021).

Pearce, E. et al. Loneliness as an active ingredient in preventing or alleviating youth anxiety and depression: a critical interpretative synthesis incorporating principles from rapid realist reviews. Transl. Psychiatry. 11, 1–36 (2021).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen. Psychiatry. 62, 593–602 (2005).

Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473 (2018).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Rubel, J. A., Rosenbaum, D. & Lutz, W. Patients’ in-session experiences and symptom change: session-to-session effects on a within- and between-patient level. Behav. Res. Ther. 90, 58–66 (2017).

Barber, J. P., Connolly, M. B., Crits-Christoph, P., Gladis, L. & Siqueland, L. Alliance predicts patients’ outcome beyond in-treatment change in symptoms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 1027–1032 (2000).

Lorenzo-Luaces, L., Derubeis, R. J. & Webb, C. A. Client characteristics as moderators of the relation between the therapeutic alliance and outcome in cognitive therapy for depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 368–373 (2014).

Steinert, C., Kruse, J., Leweke, F. & Leichsenring, F. Psychosomatic inpatient treatment: real-world effectiveness, response rates and the helping alliance. J. Psychosom. Res. 124, 109743 (2019).

Hersoug, A. G., Høglend, P., Gabbard, G. O. & Lorentzen, S. The combined predictive effect of patient characteristics and alliance on long-term dynamic and interpersonal functioning after dynamic psychotherapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 20, 297–307 (2013).

Khalifian, C. E., Beard, C., Björgvinsson, T. & Webb, C. A. The relation between improvement in the therapeutic alliance and interpersonal functioning for individuals with emotional disorders. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 12, 109–125 (2019).

Strunk, D. R., Cooper, A. A., Ryan, E. T., DeRubeis, R. J. & Hollon, S. D. The process of change in cognitive therapy for depression when combined with antidepressant medication: predictors of early intersession symptom gains. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 80, 730–738 (2012).

Webb, C. A., Beard, C., Auerbach, R. P., Menninger, E. & Björgvinsson, T. The therapeutic alliance in a naturalistic psychiatric setting: temporal relations with depressive symptom change. Behav. Res. Ther. 61, 70–77 (2014).

Zelencich, L. M. et al. Predictors of anxiety and depression symptom improvement in CBT adapted for traumatic brain injury: pre/post-injury and therapy process factors. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 26, 97–107 (2020).

Johansson, P., Høglend, P. & Hersoug, A. G. Therapeutic alliance mediates the effect of patient expectancy in dynamic psychotherapy. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 50, 283–297 (2011).

Levin, L., Henderson, H. A. & Ehrenreich-May, J. Interpersonal predictors of early therapeutic alliance in a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescents with anxiety and depression. Psychotherapy (Chic). 49, 218–230 (2012).

McEvoy, P. M., Burgess, M. M. & Nathan, P. The relationship between interpersonal problems, therapeutic alliance, and outcomes following group and individual cognitive behaviour therapy. J. Affect. Disord. 157, 25–32 (2014).

McLeod, B. D. & Weisz, J. R. The therapy process observational coding system-alliance scale: measure characteristics and prediction of outcome in usual clinical practice. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 323–333 (2005).

Tschuschke, V. et al. The role of therapists’ treatment adherence, professional experience, therapeutic alliance, and clients’ severity of psychological problems: Prediction of treatment outcome in eight different psychotherapy approaches. Preliminary results of a naturalistic. Psychother. Res. 25, 420–434 (2015).

Goldstein, L. A., Adler Mandel, A. D., DeRubeis, R. J. & Strunk, D. R. Outcomes, skill acquisition, and the alliance: similarities and differences between clinical trial and student therapists. Behav. Res. Ther. 129, 103608 (2020).

Stubbings, D. R., Rees, C. S., Roberts, L. D. & Kane, R. T. Comparing in-person to videoconference-based cognitive behavioral therapy for mood and anxiety disorders: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 15, e258 (2013).

Feeley, M., Derubeis, R. & Gelfand, L. The temporal relation between adherence and alliance to symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 67, 578–582 (1999).

Klein, D. N. et al. Therapeutic alliance in depression treatment: controlling for prior change and patient characteristics. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 71, 997–1006 (2003).

Arnow, B. A. et al. The relationship between the therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in two distinct psychotherapies for chronic depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 81, 627–638 (2013).

Falkenström, F., Kuria, M., Othieno, C. & Kumar, M. Working alliance predicts symptomatic improvement in public hospital-delivered psychotherapy in Nairobi, Kenya. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 87, 46–55 (2019).

Apolinário-Hagen, J., Kemper, J. & Stürmer, C. Public acceptability of e-mental health treatment services for psychological problems: a scoping review. JMIR Ment. Heal. 4, e10 (2017).

Aafjes-van Doorn, K. et al. Improving self‐esteemthroughintegrative group therapy for personality dysfunction: investigating the role of the therapeutic alliance and quality of object relations. J. Clin. Psychol. 75, 2079–2094 (2019).

Heynen, E., Roest, J., Willemars, G. & van Hooren, S. Therapeutic alliance is a factor of change in arts therapies and psychomotor therapy with adults who have mental health problems. Arts Psychother. 55, 111–115 (2017).

Constantino, M. J. et al. Patient interpersonal impacts and the early therapeutic alliance in interpersonal therapy for depression. Psychotherapy. 47, 418–424 (2010).

Dinger, U., Zilcha-Mano, S., McCarthy, K. S., Barrett, M. S. & Barber, J. P. Interpersonal problems as predictors of alliance, symptomatic improvement and premature termination in treatment of depression. J. Affect Disord. 151, 800–803 (2013).

Andersson, G. et al. Therapeutic alliance in guided internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment of depression, generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 50, 544–550 (2012).

Chu, B. C., Skriner, L. C. & Zandberg, L. J. Trajectory and predictors of alliance in cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 43, 721–734 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Mental Health ‘Active Ingredients’ commission awarded to Jermaine Dambi at Friendship Bench/the University of Zimbabwe. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. We would like to especially acknowledge young persons experiencing anxiety and depression for their contributions and invaluable participation throughout the review. CH receives salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Wellcome Trust, NHS, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conceptualisation: J.M.D., M.A., R.M., C.R.H., D.C., R.S. Search strategy development and refinement, database searches, including forwards and backwards searches: J.M.D., R.V., M.A., C.R.H., D.C. Article screening, data extraction and manuscript editing: R.B.C., S.M., R.S., R.M. Quality assurance and qualitative synthesis: J.M.D., R.V., R.M., M.A., C.R.H., D.C. Qualitative interviews (transcription, analysis and write-up): J.M.D., W.M., R.S., R.B.C., S.M., R.M., R.V., M.K.U., D.C. Drafting of manuscript first full version: JMD. Manuscript editing (second to fifth versions): J.M.D., W.M., R.V., M.A., C.R.H., D.C. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dambi, J.M., Mavhu, W., Beji-Chauke, R. et al. The impact of working alliance in managing youth anxiety and depression: a scoping review. npj Mental Health Res 2, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-023-00021-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-023-00021-2

- Springer Nature Limited