Abstract

Nonlinear optical gates are usually considered as fundamental building blocks for universal optical computation. However, the performance is severely limited by small optical nonlinearity, thereby bounding their operation speed, consumption energy, and device size. In this paper, we propose and experimentally demonstrate linear optical logic operations with ~3 μm-long Si wire “Ψ” gates consist of 3 × 1 optical combiners including auxiliary bias port, which maximizes the binary contrast of the output in telecom wavelength. We have demonstrated 20 Gbps Boolean “AND” operation with experimentally measured small signal loss (1.6 dB experimentally). A single Ψ gate can perform representative Boolean operations by changing the bias power and relative phases. We have also demonstrated wavelength-independent operation by seven wavelengths, which leads to wavelength-division multiplexed parallel computation. This ultrashort, highly-integrable, low-loss, and energy-efficient optical logic gates pave the way for ultralow latency optical pattern matching, recognition, and conversion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Driven by the miniaturization of the transistor gate and the development of multicore architecture, the performance of complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) computers is continuously improving as expressed by Moore’s law1. However, recent progress has been dominated by throughput improvement, and the computation latency is already saturated even with the insertion of repeaters2. This is because the miniaturization increases the wiring resistance, thereby increasing resistance-capacitance (RC) delay. This will hamper real-time information processing combined with a wideband data bus, which will be needed in the cyber-physical-system society of the future.

Discussions are underway suggesting that this limitation could be circumvented by introducing optics into a computer. Since light propagation is not affected by RC delay, this scheme may have the potential to greatly reduce computation delay if we employ nanophotonic circuits3,4,5. Most previous optical computation schemes rely on optical nonlinearity or an electro-optic effect that generally makes optical gates longer (a few 100 μm to a few mm) and energy-consuming6. In other words, latency is still limited by the intrinsic smallness of optical nonlinear effects.

Recently, there have been several proposals and some experimental demonstrations of optical logic operations employing linear optical components7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For example, a simple beam splitter can perform various types of approximate Boolean logic gates as a result of optical interference. Since these gates do not rely on optical nonlinearity, several advantages can be expected namely they can be extremely short, thereby leading to an ultrashort computation delay. Moreover, wavelength-division multiplexed (WDM) parallel computation would be possible. Thus, they are potentially promising for ultrafast and wideband optical computations. However, the demonstrated performance has been very limited because of a poor binary contrast, large loss, and a large number of unwanted reflections, arising from the difficulty involved in accurately controlling the interference while maintaining high transmittance in optical circuits. Considering the recent great progress made on Si photonic integrated circuits, especially as regards interferometers with an unprecedentedly large scale18,19,20,21,22,23, it would be important for such gates to be implemented on Si photonics technology.

In this paper, we propose and demonstrate high-bit rate optical Boolean logic operations (AND, NOR, and XNOR) realized by ultrashort (~3 μm long) Si wire-based linear “Ψ“ gates implemented on a low-loss Si photonics circuit. Our gates consist of simple 3 × 1 combiners that have three inputs and a single output. This design greatly improves the binary contrast from the theoretical limit for conventional beam splitters (1:4) to 1:9. Although a similar preliminary design has been used for plasmonic gates12, we have deliberately designed Ψ gates for Boolean operations with high transmittance, very small reflection, ideal splitting ratios, and superior wavelength insensitivity. The obtained performance is close to the theoretical limit for 3 × 1 combiners. Furthermore, we have fabricated these Ψ gates with an accurate nanofabrication process, and have succeeded in experimentally demonstrating AND, XNOR, and NOR operations using a single device with the predicted binary contrast. Because of the high transmittance and high stability, we have succeeded in demonstrating logic operations with a high bit rate (up to 20 Gbps, limited by our setup), which is already faster than that of CMOS circuits. Finally, we verify the capability for wavelength multiplexed parallel computations, which would realize the full potential of optical computation. Since the achieved Ψ gates are very short and easily integrated/combined with Si photonic circuits, our result reveals the potential of linear optic circuits for ultralow-latency computation.

Results

Design of Ψ gates

Figure 1 summarizes the principle of our logic gates. Here a Ψ gate consisting of three inputs and one output (rigorously it is a part of a 3 × 3 interferometer with extra two hidden radiation ports) is assumed, as shown in Fig. 1a. As regards the inputs, it has two different intensity-modulated bit signals (“A” and “B”) and one continuous-wave bias light with a fixed power and a fixed relative phase to signals (“Bias”). All the inputs have fixed relative phase relationships with an identical wavelength λ. Here we consider a special case for the 3 × 3 interferometer where the operation result is generated at one of the exit ports (“Output” port) when coherent beams are injected to three input ports. Assuming that the optical output signal power Pout is given as follows;

where PA and PB are the optical bit signal powers, which vary between P1 (“1” state) and P0 (“0” state). PBias is the input power for the Bias port, and TX is the transmittance from each input port X to the output port (satisfying TA + TB + TBias ≤ 1), and ΔΦ and ΔΦBias are the relative output phases of B and Bias to the output of A, respectively. In fact, this situation is possible with a cascaded network of symmetric and asymmetric (a = TBias/2TA) ideal beam splitters are shown in Fig. 1b, but here we will clarify that this function can be realized by a very simple Ψ gate implemented on Si photonic waveguides, which significantly simplifies and reduces the total size of the interferometer in comparison with the one in Fig. 1b.

a Schematic of a Ψ gate (three inputs and one output with two hidden radiation ports). b Optical circuit corresponds to (a) based on free-space optics. c Linear maps of the output port without and with the input to the Bias port for (a). x and y axes correspond to the output amplitude from the output port when ΔΦ = 0 and π, respectively. The amplitude of x axis works as AND, XNOR, and NOR operations with the maximized binary contrast BC by applying the proper input power to the Bias port.

Here, we explain how it works. Figure 1c summarizes the linear map of the Ψ gate’s output with different input conditions for Bias. Rigorously, the map for a 3 × 3 interferometer should be plotted in 3D space, but here we contract it into the 2D one. The horizontal axis represents the output port, and the vertical axis represents two other ports which we do not observe. When there is no Bias input (w/o Bias), the gate is a simple beam splitter which generates Pout(1, 1) = 2P1, Pout(1, 0) = Pout(0, 1) = 0.5P1, and Pout(0, 0) = 0 at the output port. Then, the intensity ratio is maximally 4 as regards the AND operation. Thus, the simple beam splitter functions as quasi-AND gate with a binary contrast BC of 6 dB. Once there is a non-zero Bias input (w/ Bias) with out-of-phase (ΔΦBias = π), the linear map is shifted as shown in Fig. 1c, which corresponds to Affine transformation by Bias input. Owing to this transformation, the BC of an AND operation is improved from 6 to 9.5 dB by applying PBias/P1 = TA/4TBias. This improvement of BC is very important because the computation error rate for this scheme will be determined by the finite BC. Table 1 summarizes all the parameters for all logic operations more than AND. The Ψ gate also works as XNOR with an infinite BC or NOR with a BC of ~9.5 dB when PBias/P1 = TA/TBias or PBias/P1 = 9TA/4TBias, respectively. NAND operation is also possible by satisfying PBias/P1 = TA/TBias, ΔΦ = 2π/3, ΔΦBias = −2π/312. Thus, this single gate can perform all the representative Boolean operations if we adjust ΔΦ, ΔΦBias, and PBias. It is particularly noteworthy that the operations among AND, XNOR, and NOR can be switched simply by changing PBias.

Various platforms (e.g., plasmonics9,10,11,12, photonic crystals13,14, and metasurfaces15,16,17, etc.) are now available for forming Ψ gates. Then, which platform is the best? Here, we mainly consider two performance aspects as the criteria; one is the gate length L, and the other is the signal loss SL = 10 log10 (Pout/P1) (with PBias applied for maximizing BC). L can be greatly shortened by utilizing plasmonic waveguides. However, they cannot satisfy a low SL due to the large propagation loss (>0.5 dB/μm). A preliminary study of 3 × 1 plasmonic logic gates were reported12, but these gates suffered from huge reflection and transmission loss, thereby hindering to demonstrating the superiority of linear gates, such as high-speed operations or wavelength insensitivity. In the present study, we have chosen Si photonics as a platform to satisfy the need for both a shorter L and a lower SL. Over the past decade, Si photonics has matured well, and the technology is now capable of realizing larger scale matrix switches based on interferometers21,22,23. In addition, the optical loss of Si-based waveguides and components has been remarkably reduced thanks to improvements in design and fabrication accuracy24,25. Hence, we intend to maximally enjoy these merits of Si photonics to miniaturize Ψ gates with as small as loss. Figure 2a, b shows schematics of the proposed Si wire Ψ gate with the Si layer thickness H. The structure simply consists of a single 3 μm long Y combiner with one tapered waveguide for the Bias input. Figure 2c shows an example of the simulated transmittances TA, TBias, and the signal reflectance R (from port A to A) obtained with the 3D finite element method (COMSOL) for 1.48–1.62 μm. Despite the simple design, the transmittances is surprisingly flat and large (TA = TB ~ 0.38–0.39, TBias ~ 0.20–0.22). R is still low (up to ~0.04 for the shorter λ). This means most of the residual component conveniently couples to the hidden radiation ports without reflection. This is exactly what we planned to realize at the beginning of this part in Eq. (1). Figure 2d shows the simulated AND operation for the same device as in Fig. 2c. The simulated output intensity shows that the predicted BC ~9.5 dB has been obtained with realistic structural parameters and proper input conditions. A low SL of ~0.68 dB is obtained with this maximum BC at 1.54 μm. According to Fig. 2c, an SL of 0.51–0.79 dB would be obtained for this design in the 1.48–1.62 μm range. If we modify the structural parameters, SL ≤ 0 dB (effectively loss-less) is also possible (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, Supplementary Note 1). In plasmonic systems10, a realistic figure of merit like SL has not been examined probably due to its huge propagation loss (according to our simulation, the propagation loss is estimated ~1.4 dB/μm for the metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure described in ref. 10). Even with assuming an ideal loss-less metal, TA cannot be high due to the large R (according to our simulation, R ~ 0.3 (TA < 0.25) for a 50-nm wide metal-insulator-metal waveguides based Ψ gate). Additionally, the required PBias for our device is less than a half of P1. Thus, Si-wire Ψ gates are ideal and highly feasible for low-latency linear logic operations. For the detail of designing Ψ gates, please refer Supplementary Figs. 3–5 and Supplementary Note 2.

a Schematic of the gate structure. b Top view showing the structural parameters and port numbers for S-parameter SXY (X and Y are the corresponding port number) calculations. c Simulated λ dependencies for TA, TBias and R (W = 440 nm, H = 220 nm, θ = 14.0°, Ltaper = 900 nm, Wtaper = 105 nm). The scattering boundary condition is applied as the absorption boundary, and all the transmittances are calculated from TA = |S41|2, TBias = |S43|2, R = |S11|2). d Example of simulated AND operation (λ = 1.54 μm, PBias/P1 = 0.482). Each colored image shows the intensity distributions for all the input combinations of a, b = (0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), and (1, 1). The white solid lines show the outline of the Ψ gate.

AND logic operations

Figure 3a shows the concise experimental setup for optical logic operations. 10–20 Gbps intensity-modulated optical bit patterns were generated with a desktop optical transmitter. The bit patterns were separated into two signals A and B through a 3 dB coupler, then B was delayed by a fiber delay line to shift the bit sequence. A, B and Bias were input simultaneously after their intensity and phase had been tuned by variable optical attenuators and driving digital PID regulators (See “Methods” for the experimental procedure).

a Schematic of the setup. The inset shows a scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image of the device (W ~ 480 nm, H ~ 220 nm, θ = 14.0°, Ltaper ~ 1.8 μm, Wtaper ~ 160 nm, white scale bar indicates 1 μm). A delay line (Δt) was inserted into channel B to shift the bit sequence, and then we obtain the similar result to the AND operation with a couple of pseudo-random bit sequence. b Time waveforms of inputs A, B and Output without and with Bias for AND operation. c Magnified and overlapped time waveforms of all the inputs and outputs for comparison. d Eye pattern (number of average: 16) without Bias against 20 Gbps non-return-to-zero pseudo-random bit pattern inputs. e Eye pattern with Bias for AND operation. f Simulated eye pattern of output intensity reproducing the experimental result without Bias. g Simulated eye pattern of output intensity reproducing the experimental result with Bias.

Figure 3b, c summarize the experimental average time waveforms comparing 10 Gbps AND operations without and with Bias. Apparently, we observed a much clearer AND operation with BC ~9.3 dB when we applied a PBias/P1 of ~0.62. The transmittances are TA ~ TB ~ 0.32, TBias ~ 0.20 at λ ~ 1.55 μm, which are very close to the predicted values. The optimum bias power value given by PBias/P1 = TA/4TBias is estimated to be ~0.39, which is ~63% of the experimental value. This is because the experimental optical input bit patterns are not ideal and have a finite extinction ratio ER (defined as 10 log10(P1/P0), and limited by the used optical transmitter) in the 13–23 dB range. For example, when ER ~20 dB, the analytical PBias/P1 can be calculated to be ~0.68 and is pretty close to the above experimental value (please see the plotted curve for AND operation in Supplementary Fig. 1a). This also implies that we can obtain a maximized BC of ~9.5 dB by applying a properly calibrated PBias/P1 even with ER-degraded signals (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 1). This feature can be emphasized as one of the noteworthy functionalities of Ψ gates. From Fig. 3c, we can see that the output waveform follows the rise and fall of the input signals instantaneously, indicating that the response time of the device appears to be limited only by the input signals and thus the intrinsic speed would be much faster. Figure 3d, e shows the eye pattern without and with Bias measured with 20 Gbps non-return-to-zero pseudo-random bit pattern inputs (29 − 1). The output against inputs of (0, 0), (1, 0), and (0, 1) are merged into a single level after applying Bias, which directly visualizes the improvement of BC in the bit stream. As shown in Fig. 3f, g, very similar eye patterns are reproduced in simulations based on experimental parameters (Supplementary Fig. 6). From the simulated eye patterns, the Q factors (bit error rates: BER) without and with Bias are calculated as ~4.7 (~10−6) and ~17 (~10−66), respectively. The simulated Q is mainly limited by the intensities and phase noises of the input signals (according to the measurement of the noise spectral density for our electric signal generator (MP1800A, Anritsu), −140 dBm/Hz was employed for simulations) (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 3). Therefore, the computation error rate can be greatly improved by applying Bias.

Switching to the other operations with a single device

To experimentally prove the reconfigurability of a single Ψ gate as explained in Fig. 1c and Table 1, Fig. 4a, b shows the experimental XNOR and NOR operations simply by changing PBias. Both operations have also been clearly demonstrated with using the same device shown in Fig. 3. The XNOR and NOR operations exhibit BC values of >10 dB and ~9 dB with PBias/P1 ~1.6 and 3.1, respectively. These values roughly correspond to the analytical PBias/P1 (1.6–1.9 for XNOR, 3.5–3.7 for NOR) considering the experimental finite ER (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1). The response speed in Fig. 4c, d is again limited by the inputs. It would be worth to note that the NOR operation is more important because it works as a universal gate set for all logic operations.

Wavelength insensitive operation

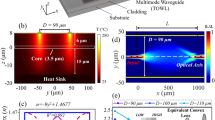

Figure 5 shows the λ dependence of the same device. Figure 5a shows experimental and simulated spectra for TA, TBias, and R. After subtracting the fiber-chip coupling loss, we experimentally obtained TA ~ TB = 0.25–0.35, and TBias = 0.11–0.32 for the 1480–1620 nm range. Using the experimental TA and TBias, we estimated PBias//P1 and SL for AND operation as shown in Fig. 5b. Even with the assumption of ER = 20 dB, PBias//P1 < 1 is achieved over the entire measurement range. The SL is degraded compared with the simulation result shown in Fig. 2 because the experimental design has a smaller TA. But, an SL of a few dB is still much smaller than in any other previous reports8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Figure 5c overlaps time waveforms of the AND operations of seven different λ (1535, 1540, 1545, 1550, 1555, 1560, and 1565 nm) denoted by the dots in Fig. 5b. By calibrating PBias/P1 for each λ, a similar BC was achieved for all the tested λ. In this demonstration, the input signal bit sequences and the operations are the same for all λ. It should be noted, however, we can perform simultaneously different operations for each wavelength channel by varying the input conditions (that is, totally independent parallel logic operations is possible up to the number of the input channel with a single gate). This is very unique and ultimate benefit of our linear gates compared to nonlinear gates.

a TA, TB, and R spectra of the device. Thin and thick solid lines denote the data before and after the moving average, respectively. The broken lines denote the simulated results based on the actual shape of the measured sample. b Estimated PBias/P1 (under ER = 20 dB and ∞ dB) and SL for maximizing binary contrast BC of AND operations from the measured TA and TBias in (a). Thin and thick solid lines denote the data before and after the moving average, respectively. The colored dots denote the experimental PBias/P1 values for each wavelength corresponding to (c). The error bars are determined by the standard deviation of input signal levels P0 and P1. c Overlapped time waveforms of signal inputs and the AND outputs with seven different λ values. The violet, blue, cyan, green, orange, yellow, and red curves correspond to 1535, 1540, 1545, 1550, 1555, 1560, and 1565 nm, respectively.

Discussion

The power consumption of a Ψ gate is simply given by the total optical input power including Bias. If the experimental net loss of ~5 dB (for AND operation at λ = 1550 nm, Supplementary Note 1) and a typical minimum input power of commercial photodetectors of −20 dBm are assumed, the total optical input power becomes −15 dBm. Therefore, the energy consumption per bit for the demonstrated bit rate (20 Gbps) is ~1.7 fJ/bit. As it can be seen in the spectral response shown in Fig. 5a, ultrashort (or ultrathin) linear gates are essentially ultra-broadband15,26. We have also tried 40 Gbps operation (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Note 4), and we found that the operation bit rate is basically limited by the rise and fall time of the optical input signals. The power consumption can be reduced down to sub fJ/bit order by integrating nanophotodetectors with much smaller capacitance27 or by employing much higher bit rate >100 Gbps.

The phase sensitivity of performances is actually not very severe. For instance, the total phase error δϕtot (=\(\sqrt {\delta \phi ^2 + \delta \phi _{\mathrm{Bias}}^2}\)Z, δϕ: the relative phase error between A and B, δϕBias: the relative phase error between A and Bias) can be up to ~ ± 0.18 rad (~ ± 6%) to satisfy BC > 9.0 dB, and SL < 1.7 dB with the experimental transmittances (TA = 0.31, TBias = 0.20).

For future work, the proposed Ψ gates should be applied for optical information processing by cascading many gates. However, we can only cascade AND or NOR gates because the cascade connection of the other gates are not linearly separable. For multiple AND operations while cascading Ψ gates, BC becomes ~4.4 dB, ~2.2 dB, and ~1.1 dB if we increase the number of input as 4-bit, 8-bit, and 16-bit, respectively. We note that the feasibility and the performances (computation latency, error rate, etc.) are not directly determined by the BC, but we should also consider the optical input and the reception intensity, electrical noises, the performances of the on-chip OE converter and the electrical threshold operator. If the reception intensity is sufficiently high, it may be feasible to operate 128-bit AND circuits. We have initially considered a brief configuration for 128-bit AND circuits by cascading the Ψ gates, and estimated ~10 times shorter latency than one of the fastest CMOS AND circuits28. Such a large-scale AND circuits are significant to realize ultralow-latency pattern matching applications.

In conclusion, with the aim of realizing ultralow latency optical computation, we proposed and experimentally demonstrated ultrashort, simple, integrable, and low-loss Si wire Ψ linear optical logic gates. The loss is much lower than any other optical gates. This also improves the latency of optoelectrical conversion for same energy consumption. The operation function can be switched among AND, XNOR, and NOR with a single Ψ gate by tuning PBias. It is also possible for WDM computation to boost the throughput because of the small wavelength dependence. In the near future, more than 1–10 Tbps will be available by cascading Ψ gates for multibit operations. The integrated electro-optic phase shifters should also be much shorter and faster. To demonstrate ultralow latency operation, we must also integrate optoelectrical converters.

As mentioned in the introduction, we need to satisfy strict criteria for optical logic gates applied to universal computation29. However, we repeat that the proposed gate could be designed for lower latency computing with specific applications requiring few optical nonlinear gates. For instance, this gate could be applicable for such devices as pattern recognizers/matchers30 by combining them with a low-latency electrical thresholding device (e.g., sense amplifiers31).

Methods

Fabrication

The sample was fabricated on a silicon-on-insulator substrate with a 220 nm-thick top Si layer. An e-beam resist (ZEP-520A, Zeon) was spin-coated on the substrate, and the resist pattern was formed after e-beam writing and development. The resist pattern was transferred to the Si layer by using dry etching. After the resist was removed, polymer (SU-8 2002, MicroChem) spot size converters32 were fabricated for the input/output ports by using 2nd e-beam lithography.

Measurement with optical phase lock loops

Two coherent input signal lights and one invariant light were prepared by splitting the light from the same tunable laser diode source (81600B, Agilent) by using variable optical couplers (Model 905P, Evanescent Optics). Optical bit patterns up to 40 Gbps were generated through an optical transmitter (46120C, SHF) driven by a signal generator (MP1800A, Anritsu) with a MUX system (MP1861A, Anritsu). The intensity of each optical signal was adjusted and balanced with a multichannel variable optical attenuator (VOAB-Series, Bola). These optical signals were coupled to the fabricated chip by using a 6 channel lens module with a 50 μm output spacing. To suppress the phase fluctuations caused by mechanical vibration, two channels of a fiber stretcher (PZ1-PM1-APC-E-155P, Optiphase) were installed in channels A and B (Bias was set as the phase standard). Both fiber stretchers were controlled by employing a digital laser stabilizer (LaseLock, TEM Messtechnik). After locking the phase relationships, the average time waveforms and eye patterns of the output signal were detected with an optical sampling oscilloscope (N1046A, Keysight) through an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (PMFA-30, Pritel) and a tunable optical band pass filter (CVF-220CL, Alnair Labs). By referring to the time average output waveforms displayed in the oscilloscope, we tried to obtain a better BC by manually tuning P1, PBias, and relative phases by changing the parameters in the PID regulator. More information on the optical phase lock loop and its optical I/O system is available in Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9, and Supplementary Notes 5 and 6. If all modulators and Ψ gates are on a same chip, we do not need to employ this sort of phase lock loops (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Note 7 for the preliminary demonstration of integrated linear logic circuits). For the results for other logic operations without Bias, please refer to Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Note 8.

Data availability

All the experimental and simulated data are available in this paper. For more technical information, we provide the relevant data in the Supplementary Information. Further supporting information could be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rupp, K. 42 Years of Microprocessor Trend Data. https://github.com/karlrupp/microprocessor-trend-data/tree/master/42yrs (2018).

IEEE International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS) 2017 Edition. https://irds.ieee.org/roadmap-2017 (2017).

Caulfield, H. J. & Dolev, S. Why future supercomputing requires optics. Nat. Photon. 4, 261–263 (2010).

Hardy, J. & Shamir, J. Optics inspired logic architecture. Opt. Express 15, 150–165 (2007).

Ishihara, T., Shinya, A., Inoue, K., Nozaki K., & Notomi M. An integrated optical parallel adder as a first step towards light speed data processing. Proc. of the 13th International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC 2016): Smart SoC of Intelligent Things, 123–124 (2016).

Hinton, K., Raskutti, G., Farrell, P. M. & Tucker, R. S. Switching energy and device size limits on digital photonic signal processing technologies. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 14, 938–945 (2008).

Ogusu, M., Tanaka, S. & Kuroda, K. Optical logic operations using three-beam phase-conjugate interferometry. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 29, 1265–1267 (1990).

Larom, B., Nazarathy, M., Rudnitsky, A., Nevet, A. & Zalevsky, Z. Cascadable and reconfigurable photonic logic gates based on linear lightwave interference and non-linear phase erasure. Opt. Express 18, 13600–13607 (2010).

Wei, H., Wang, Z., Tian, X., Käll, M. & Xu, H. Cascaded logic gates in nanophotonic plasmon networks. Nat. Commun. 2, 387 (2011).

Fu, Y. et al. All-optical logic gates based on nanoscale plasmonic slot waveguides. Nano Lett. 12, 5784–5790 (2012).

Ota, M., Sumimura, A., Fukuhara, M., Ishii, Y. & Fukuda, M. Plasmonic-multimode-interference-based logic circuit with simple phase adjustment. Sci. Rep. 6, 24546 (2016).

Peng, C. et al. Universal linear-optical logic gate with maximal intensity contrast ratios. ACS Photon. 5, 1137–1143 (2018).

Salmanpour, A., Mohammadnejad, S. & Bahrami, A. Photonic crystal logic gates: an overview. Opt. Quantum Electron. 47, 2249–2275 (2015).

Hussein, H. M. E., Ali, T. A. & Rafat, N. H. New designs of a complete set of photonic crystals logic gates. Opt. Commun. 411, 175–181 (2018).

Xomalis, A. et al. Fibre-optic metadevice for all-optical signal modulation based on coherent absorption. Nat. Commun. 9, 182 (2018).

Achouri, K., Lavigne, G., Salem, M. A. & Caloz, C. Metasurface spatial processor for electromagnetic remote control. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 64, 1759–1767 (2016).

Papaioannou, M., Plum, E., Valente, J., Rogers, E. & Zheludev, N. I. Two-dimensional control of light with light on metasurfaces. Light. Sci. Appl. 5, e16070 (2016).

Soref, R. The past, present, and future of silicon photonics. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 12, 1678–1687 (2006).

Thomson, D. et al. Roadmap on silicon photonics. J. Opt. 18, 073003 (2016).

Morrissey, P. E., Gradkowski, K., Carroll, L. & O’Brien, P. Packaging of silicon photonic devices: from prototypes to production. Proc. SPIE 10537, 105370L (2018).

Suzuki, K. et al. Low-insertion-loss and power-efficient 32 × 32 silicon photonics switch with extremely high-Δ silica PLC connector. J. Light. Technol. 37, 116 (2019).

Qiao, L., Tang, W. & Chu, T. 32 × 32 silicon electro-optic switch with built-in monitors and balanced-status units. Sci. Rep. 7, 42306 (2017).

Seok, T. J. et al. Wafer-scale silicon photonic switches beyond die size limit. Optica 6, 490–494 (2019).

Xu, D. et al. Silicon photonic integration platform—have we found the sweet spot? IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 20, 8100217 (2014).

Tran, M. A. et al. Ultra-low-loss silicon waveguides for heterogeneously integrated. Silicon/III-V. Photonics Appl. Sci. 8, 1139 (2018).

Nalla, V., Valente, J., Sun, H. & Zheludev, N. I. 11-fs dark pulses generated via coherent absorption in plasmonic metamaterial. Opt. Express 25, 22620–22625 (2017).

Nozaki, K., Matsuo, S., Shinya, A. & Notomi, M. Amplifier-Free Bias-Free Receiver Based on Low-Capacitance Nanophotodetector. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 24, 4900111 (2018).

Arsovski, I. & Sheikholeslami, A. A mismatch-dependent power allocation technique for match-line sensing in content-addressable memories. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuit 38, 1958–1966 (2003).

Miller, D. A. B. Are optical transistors the logical next step? Nat. Photon. 4, 3–5 (2010).

Kim, S., Goda, K., Fard, A. & Jalali, B. Optical time-domain analog pattern correlator for high-speed real-time image recognition. Opt. Lett. 36, 220–222 (2011).

Wicht, B., Nirschl, T. & Schmitt-Landsiedel, D. Yield and speed optimization of a latch-type voltage sense amplifier. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 39, 1148–1158 (2004).

Shoji, T., Tsuchizawa, T., Watanabe, T., Yamada, K. & Morita, H. Low loss mode size converter from 0.3 μm square Si wire waveguides to singlemode fibres. Electron. Lett. 38, 1669–1670 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. O. Moriwaki, Dr. T. Tamamura, Dr. E. Kuramochi, and Dr. M. Ono for undertaking the fabrication work. The authors thank Dr. T. Inagaki and Dr. T. Umeki for advice and for lending us the instruments needed for the optical phase lock loop systems. We thank Prof. T. Ishihara, Prof. K. Inoue, Prof. S. Kawakami, Prof. S. Iwamoto, and Prof. Y. Ota for fruitful discussions. The authors thank Dr. S. Sergent, Dr. F. Tian, and Dr. H. Sumikura for daily discussions. This work was supported by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (JPMJCR15N4), Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and M.N. conceived the basic idea for this work. S.K. and M.N. carried out the theoretical analysis. S.K. performed the finite element method simulations needed for the design. S.K. carried out fabrication, measurements, and evaluations. K.N. wrote codes for efficient and stable measurements, and helped to build the setup. K.T. supported the building of the optical phase lock loops. A.S. and M.N. obtained the funding and supervised this work. S.K. wrote the first draft of this paper. All the authors contributed to the revision of this paper and agreed on the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kita, S., Nozaki, K., Takata, K. et al. Ultrashort low-loss Ψ gates for linear optical logic on Si photonics platform. Commun Phys 3, 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0298-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0298-2

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Research on silicon waveguide crossing for optical logic operations at telecommunication wavelength

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2024)

-

Realization of optical logic gates using on-chip diffractive optical neural networks

Scientific Reports (2022)