Abstract

Trapped cold molecules represent attractive systems for precision-spectroscopic studies and for investigations of cold collisions and chemical reactions. However, achieving their confinement for sufficiently long timescales remains a challenge. Here, we report the long-term trapping of Stark-decelerated OH radicals in their X 2Π3/2 (ν = 0, J = 3/2, MJ = 3/2, f) state in a permanent magnetic trap. The trap environment is cryogenically cooled to a temperature of 17 K to suppress black-body-radiation-induced pumping of the molecules out of trappable quantum states and collisions with residual background gas molecules which usually limit the trap lifetime. The cold molecules are thus confined on timescales approaching minutes, an improvement of up to two orders of magnitude compared with room temperature experiments, at translational temperatures of ∼25 mK. The present results pave the way for new experiments using trapped cold molecules in precision spectroscopy, in studies of slow chemical processes at low energies and in the quantum technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last two decades, impressive progress has been achieved in the generation of translationally cold molecules1,2,3,4,5,6 motivated by a range of promising applications7,8,9,10. These include spectroscopic precision measurements for the exploration of physics beyond the standard model8,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, studies of collisions and chemical reactions at very low temperatures18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and new approaches to quantum simulation27,28 and quantum information29,30. Many of these experiments require the interaction of the cold molecules with either radiation or other particles in traps over extended periods of time.

Several methods have been demonstrated for the trapping of cold molecules. Cold polar molecules produced by Stark deceleration31,32 or by velocity selection followed by Sisyphus cooling have been stored in electrostatic traps33,34,35,36,37. Paramagnetic molecules decelerated to low velocities38, generated using a cryogenic-buffer-gas source39 or produced by photodissociation40, have been confined in electromagnetic39,41, permanent magnetic40,42,43,44,45,46,47 and very recently superconducting magnetic traps48. Optical trapping of cold molecules formed by photoassociation49 or magnetoassociation50 has also been demonstrated. Recently, the first magneto-optical traps for molecules have been implemented51,52.

With few exceptions (see, e.g., refs. 34,36,37,53), trap lifetimes of cold polar molecules that have been achieved in previous studies range typically from milliseconds to a few seconds which is far less than what has been achieved with neutral atoms in atom traps and particularly with ions in ion traps3,54. There are several reasons for this. Energetic collisions with background gas molecules, which can occur on timescales of seconds even under the ultrahigh-vacuum conditions of typical experiments, usually impart sufficient kinetic energy to the confined molecules to eject them from the shallow traps. Similarly, chemical reactions with background molecules remove density from the trap55. Moreover, in many experiments the lack of a continuous cooling mechanism for the trapped molecules limits their temperatures, densities and lifetimes. Of imminent importance for trapped polar molecules, however, is their interaction with the ambient black-body radiation (BBR) field. BBR can continuously pump them into quantum states which are not magnetically or electrically trappable and therefore lead to the loss of their confinement33.

These limits on the trap lifetime represent a severe impediment for several applications of cold molecules. Precision-spectroscopic measurements require long interaction times of the radiation with the molecules1,7,8. Studies of chemical reactions with cross sections far below the collision limit, which represent the vast majority of all chemical processes, equally require long contact times between the collision partners to obtain a significant reaction yield. This problem is further aggravated by the low number densities of trapped molecules achieved so far. Consequently, studies of reactions with trapped molecules have thus far been limited to fast processes19. Similarly, many applications in quantum science also require long trapping and coherence times of the particles. Indeed, the capability to store and coherently manipulate cold ions for minutes has been one of the main reasons for the impressive success of ion-trap-based approaches to quantum computing56.

In this paper, we report the cryogenic magnetic trapping of Stark-decelerated molecules on timescales approaching minutes, exceeding previous room temperature studies by one to two orders of magnitude. The cryogenic environment efficiently reduces the intensity of the ambient BBR field and further improves the vacuum conditions enabling a marked improvement of the trapping times. The trap lifetime achieved here is similar to the one reported in previous cryogenic trapping experiments of molecules loaded from buffer-gas53 or velocity-selection sources34,36,37. With Stark deceleration being one of the most important techniques for the generation of cold polar molecules2, the present results lay the foundations for new experiments using trapped cold molecules in precision spectroscopy, in studies of slow chemical processes at low energies and in the quantum technologies.

Results

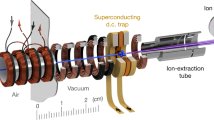

Our experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. Packages of internally cold OH radicals were produced by an electric discharge of H2O vapour seeded in 2.5 bar Kr gas during a supersonic expansion into high vacuum57. The molecule package propagated through a skimmer into a Stark decelerator58 in which it was slowed down for subsequent loading into a cryogenic permanent magnetic trap (inset in Fig. 1).

Experimental setup. Pulsed beams of internally cold OH radicals were generated by a pinhole discharge gas nozzle (1). After passing through a skimmer (2), the molecules were decelerated from velocities of 425 m/s down to 29 m/s by a 124-stage Stark decelerator (3). The translationally cold molecules were loaded into a permanent magnetic trap (7) by applying high voltages to the bar magnets (8) and stopping wires (9) acting as a last deceleration stage. The whole trap assembly was mounted on a xyz-translation stage (6) for fine adjustment of its position. Free-flying decelerated or trapped molecules were detected by laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) collected by a lens onto a photomultiplier tube (PMT) (5). The trap region was shielded from stray light using light baffles (4). The blue line shows the laser axis (10). The inset shows a side-view schematic of the trapping region

Stark deceleration

Packages of translationally cold OH radicals in the X 2Π3/2(v = 0, J = 3/2, MJ = ±3/2, f) state were produced by Stark deceleration using a 124-stage decelerator (“Methods”). Here, v denotes the vibrational quantum number of the molecule, J is the quantum number of its total angular momentum without nuclear spin and MJ is the corresponding space-fixed projection quantum number. f designates the parity label.

The OH molecules were probed by monitoring their laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) (“Methods”). Experimental time-of-flight (TOF) profiles of the molecules were validated against simulated TOF curves, as depicted in Fig. 2a–d (see Supplementary Note 1 for details). The simulations take into account contributions from both low-field-seeking components MJΩ = −9/4 and MJΩ = −3/4 which were transported through the decelerator (Ω denotes the quantum number of the projection of J onto the molecular axis). As can be seen in Fig. 2a–d, the simulations accurately reproduce the experimental arrival time of the OH packages as well as the relative LIF signal intensities. All TOF traces in Fig. 2a–d were normalised to the signal in guiding mode (Fig. 2a, c, vinitial = vfinal = 425 m/s). By comparing the experiments with the simulations, a spatial spread of the initial OH packet of 13.5 mm (full width at half maximum, FWHM) was deduced. Due to the large spatial and velocity spreads of the molecular beam, three-phase-stable regions were loaded and transported through the decelerator as indicated by the phase-space diagrams depicted in Fig. 2g, h. This gives rise to a distinct triple-peak structure in the centre of the TOF profile of Fig. 2a, c. Upon increasing the phase angle of the decelerator58, more energy is removed from the OH package per decelerator stage and the number of molecules (and therefore the signal level) decreases due to a reduction of the phase-stable volume. At a phase angle of ϕ = 55.468°, the target velocity for loading at vtarget = 29 m/s was reached. The corresponding signal level (Fig. 2b, d) was ≈70 times lower than the one observed in guiding mode. During the free flight over a distance of 11.5 mm between the decelerator exit and the detection point at the low final velocity of 29 m/s, the phase-space volume rotated significantly (Fig. 2h) so that the signal in the TOF profile appears broadened.

Time of flight (TOF) profiles of OH molecules and corresponding phase-space distributions. All TOF profiles were recorded by collecting laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) of OH molecules in the trap centre 11.5 mm downstream from the exit of the Stark decelerator. a, b, e show the experimental TOF data, the corresponding Monte-Carlo trajectory simulations are shown in c, d, f. All TOF traces are normalised with respect to the maximum signal level given in a, c which were obtained in guiding mode (no deceleration, i.e., vinitial = vfinal = 425 m/s). b, d show TOF profiles at the targeted loading velocity of vtarget = 29 m/s. e, f show TOF traces illustrating the final deceleration and the onset of trapping at room temperature. The period of application of the electric stopping field, by which the mean forward velocity of the molecule packet is reduced from 29 m/s to 0 m/s, is indicated in e by two blue vertical lines. g Phase-space distribution of the OH package at the arrival time of the synchronous molecule in the trap centre for the decelerator operating in guiding mode (see a, c). Due to the large spatial and velocity spread of the molecular beam, a total of three phase-stable regions were loaded and transported through the decelerator. The packet indicated in red pertains to the signal maximum. h Phase-space distribution at vtarget = 29 m/s. The fastest phase-stable package is not shown. The phase-space volume is tilted due to the free flight from the decelerator to the trap. The packet indicated in red was selected for trap loading. i–l Phase-space evolution at different points in time after loading the trap, extracted from the simulations shown in f. The contour lines indicate the phase-space acceptance of the trap in increasing order of energy: 0.02 (magenta), 0.06 (green), 0.08 (yellow), 0.10 (red) and 0.12 (blue) cm−1. Uncertainties correspond to the standard error of five experimental repetitions in e

Cryogenic magnetic trap

The magnetic trap consisted of two Ni-coated bar magnets generating a quadrupolar magnetic field. Similar trap designs have been reported in, e.g., refs. 40,59,60. We employed PrFeB as material for the magnets instead of the more widely used NdFeB because the latter exhibits a decreased magnetisation level at cryogenic temperatures due to a spin-reorientation transition61. By contrast, the remanence of the PrFeB magnets was specified to increase from 1.40 T at room temperature to 1.64 T under cryogenic conditions62. The entire trap assembly was mounted on a xyz-translation stage allowing fine adjustment of the position of the magnets with respect to the exit of the decelerator in order to optimise the loading efficiency.

The trap was enclosed in a two-layer cryogenic shield consisting of copper plates cooled by a closed-cycle refrigerator. The cold head of the refrigerator was suspended from a spring-loaded assembly and connected to the cryogenic shield with copper braids in order to isolate the trap from vibrations. Temperatures of 17 K at the inner shield and of 53 K at the outer shield were thus obtained. As the BBR intensity scales with the temperature T as T4, the cryogenic environment effectively suppressed BBR pumping of the trapped molecules into untrapped states (Supplementary Note 3).

The shielding of the trap from room temperature BBR was, however, not perfect because of apertures in the assembly necessary for admitting the molecular beam, for inserting laser beams enabling the spectroscopic probing of the trapped molecules and for collecting their LIF. The presence of the cryogenic shields imposed a significant reduction in the solid angle under which fluorescence photons could be collected. In the present experiments, fluorescence from the molecules in the trap was acquired with a lens (∅ = 6 mm, focal length f = 6 mm) mounted in the cryogenic shield. Therefore, inevitably the LIF signal levels obtained were low, but nonetheless sufficient for an unambiguous characterisation of the trap loading dynamics.

Trap loading

Efficient transfer of the decelerated OH package into the magnetic trap required a careful minimisation of particle losses during the loading procedure. Successful trap loading necessitates minimising the mismatch between the phase-stable volume transported by the decelerator and the trap. During free flight after exiting the decelerator, the molecule packages expand in both the longitudinal and transversal directions. Therefore, placing the trap close to the decelerator helps to prevent losses. In practice, this requirement is mitigated by the presence of the two cryogenic shields and a safety distance that has to be held towards the last high voltage electrode of the decelerator. As illustrated in the inset of Fig. 1, the loading process was designed such that the bar magnets forming the magnetic trap also serve as a last electrostatic deceleration stage. This allows for loading the trap with molecules at higher velocities, since the final deceleration step occurs in close proximity to the trap centre42,59. In addition, four wire electrodes were spanned in between the magnets to introduce further degrees of freedom in shaping the stopping fields.

The complexity of the stopping geometry and the considerable amount of parameters influencing the loading efficiency render it difficult to design and optimise the trapping process manually. Therefore, salient experimental parameters such as the voltages on the magnets and stopping wires as well as the phase angle of the deceleration process were numerically optimised using a mesh-adaptive search algorithm63,64 (Supplementary Note 2). For the experiments presented here, the potentials on the bar magnets were limited to ±5.8 kV by the electric breakdown strength of the trap. Figure 3a shows the stopping potentials expressed as Stark energies for OH in the X2Π3/2 (J = 3/2, MJ = ±3/2, f) state allowing the removal of a maximum energy of 0.76 cm−1 in the longitudinal direction along the centre line through the trap (y, z = 0). For comparison, the Zeeman trapping potential EZm for the X2Π3/2 (J = 3/2, MJ = +3/2, f) state in between the two 1.64 T PrFeB magnets is depicted in Fig. 3b. The resulting magnetic trap has a depth of 0.14 cm−1 along the longitudinal x-direction (corresponding to a maximum velocity of 13.9 m/s for OH radicals in this state) as well as 0.33 cm−1 (21.7 m/s) and 0.13 cm−1 (13.3 m/s) along the transverse y- and z-directions, respectively. Note that from the packet of decelerated molecules, only those in the low field seeking J = 3/2, MJ = +3/2, f Zeeman component can be confined magnetically42,59. This comprises half of the molecules in the decelerated ensemble. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the Stark energy slope extends beyond the trap centre and allows for matching the deceleration in Fig. 3d to the velocity distribution of the incoming OH package, see Supplementary Note 2.

Stopping and trapping potentials. a Stark energies ESt for OH in the J = 3/2, MJ = ±3/2, f state resulting from applying an electric potential of ±5.8 kV on the bar magnets and the rear stopping wires. The stopping wires closer to the decelerator exit are kept at ±2.3 kV. b Zeeman energies EZm for OH in the J = 3/2, MJ = +3/2, f state assuming a remanence of the permanent magnets of 1.64 T. c Stark/Zeeman energy profile along the stopping direction (y, z = 0). The black vertical bar represents the trap centre and the horizontal dashed line corresponds to the kinetic energy of the synchronous molecule at the decelerator exit. d Longitudinal acceleration ax for OH molecules according to the Stark and Zeeman energies from c. All distances are given relative to the trap centre

Trapping of OH molecules

To load the decelerated molecules into the magnetic trap, the stopping fields were switched on in between the points in time indicated by blue vertical lines in Fig. 2e. The TOF curve depicting the onset of trapping is shown in Fig. 2e, f. During the stopping process, the mean forward velocity of the molecule packet was reduced from 29 to 0 m/s for loading the trap. The TOF profile of the molecules right after trap loading displays an oscillatory pattern which is due to the molecule packet oscillating inside the trap. This behaviour is reproduced by the simulations. The decrease in signal intensity is attributed to the loss of molecules in magnetically high-field seeking states as well as the portion of molecules carrying sufficient kinetic energy to surmount the trap potential. The phase-space evolution of the trapped OH cloud as extracted from the simulations is depicted in Fig. 2i–l. The simulations indicate that the trap loading is completed after 2.7 ms and after 0.1 s the molecule package has obtained an average velocity of 6.0 m/s (corresponding to a translational temperature of 25 mK).

The LIF signals of the trapped molecules as a function of the trapping time at room and cryogenic temperatures are shown in Fig. 4. The data are consistent with a mono-exponential decay. At room temperature, the 1/e lifetime for the confinement of the molecules was determined to be 0.6(2) s (Supplementary Note 4 and Table 1). This trap lifetime is comparable to the one found in ref. 59, where a similar trap geometry was used.

Lifetime of trapped OH molecules. Fractional population of trapped OH radicals as a function of trapping time at room temperature (295 K, red) and under cryogenic conditions (17 K, black and grey). The grey data points were obtained by subtracting experimentally determined background levels from each individual data point prior to fitting. The black data points result from the subtraction of a mean background value from the trapping signal. The dashed lines correspond to fits of the data to an exponential decay function. The 1/e lifetime determined from the fits is 0.6(2) s at 295 K (red) and 24(13) s (grey) as well as 23(8) s (black) at 17 K. The time origin coincides with switching off the stopping fields. Uncertainties correspond to the standard error of 500–1200 and 121 experimental cycles for the room temperature and cryogenic data, respectively

To assess whether the current trap lifetime is limited by BBR pumping or ejection of the trapped molecules by collisions with background gas, we modelled the trap lifetime due to interaction with BBR and background gas collisions. For this purpose, we calculated the transition rates between the energy levels under the influence of BBR pumping and collisions with background gas molecules at a certain pressure and solved the relevant rate equations (Supplementary Note 3). We estimate a purely radiative lifetime of 2.8 s which is in agreement with the results from Hoekstra et al.33. The fact that our experimental result is more than a factor of 4 lower suggests that in this regime the trap lifetime is still likely to be limited by collisions with background gas. Assuming constant background pressure, the Kr gas pressure inside the trapping region was estimated to be 4 × 10−8 mbar. This is a reasonable value considering that the fast part of the molecular beam is reflected off the surfaces of the cryogenic shield and the gas molecules remain in the trapping region for some time before they can escape through the apertures to be pumped away. Under cryogenic conditions (17 K), the holding duration in the trap was increased to up to 10 s, and a 1/e trapping lifetime of 23(8) s was determined under these conditions. This value is about a factor of 3 smaller than the expected limit from BBR pumping (see Table 1). This result indicates that in this regime the lifetime is considerably enhanced, but likely still limited by collisional processes. While most gases should efficiently freeze out on the cryogenic shields surrounding the trap, these residual collisions could originate from gas particles streaming into the trapping region through the apertures in the cryogenic shield and hitting the OH molecules before they freeze out on the surfaces. Other likely contributions are collisions with hydrogen molecules which are not expected to freeze out efficiently on the surfaces under the UHV conditions and cryogenic temperatures of the present experiment. Assuming that the trap lifetime is limited by the collision rate with H2 molecules at 17 K, an effective H2 pressure of 3 × 10−11 mbar in the trapping region can be deduced from this lifetime. This value is of the same order of magnitude as the typical pressures measured by a pressure gauge in the trap chamber surrounding the cryogenic shield.

Discussion

The observed enhancement of the trapping time of the cold OH molecules in the cryogenic environment amounts to a factor of 40 with respect to room temperature and to almost a factor of 10 compared with the previous result of ref. 33. The current trap lifetime is attributed to collisions with residual gas. This conclusion is supported by the observation that the measured trap lifetime fluctuated slightly on timescales of several days probably as a result of slightly changing vacuum conditions in the setup. The effective trap lifetime, therefore, critically depends on the experimental conditions and the values presented here are typical values achievable with the present setup.

Besides collisions with the background gas and pumping by BBR, loss of OH radicals from the trap can also result from Majorana-type transitions in proximity to the field-free trap centre and from nonadiabatic spin-flip transitions in crossed electric and magnetic fields65,66,67,68,69. In our experiments, an electric field is applied to the trap for a short duration of 287.9 μs while loading the molecules. As can be inferred from comparing the signal levels in Fig. 2b, e, the loss of OH radicals observed during this period is on the order of 50%. This is in line with the expected retention of only one half of the molecules in the decelerated packet in the trap, i.e., those which correspond to magnetically low-field seeking molecules (see above). We thus surmise that loss by spin-flip transitions only plays a minor role during the loading phase of the experiment. After loading, the trapped molecules solely evolve under the influence of a quadrupolar magnetic field. Majorana-type losses can in principle occur during the hold time of the molecule in the trap. However, the trap loss observed still seems to be dominated by collisions with residual background gas as discussed above. We also note that losses due to inelastic collisions between OH radicals do not appear to play a dominant role at the trap densities prevailing in the present experiments.

Consequently, a further increase of the trap lifetime should be obtainable by transporting the trapped molecules into a “darker” region of the assembly with an even further reduced exposure to gas as well as room temperature BBR entering the trapping region from outside the cryogenic shield. This facility is currently being implemented in our setup.

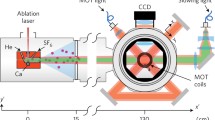

The trapping times achieved in the present study are sufficiently long to enable prolonged spectroscopic measurements on the trapped molecules and the measurement of slow reactive processes, enabling a new range of applications for cold trapped molecules. In this context, an intriguing perspective is the simultaneous trapping of the cold molecules with cold trapped ions6,70 which paves the way for ion-neutral hybrid systems of purely molecular matter. Experiments in this direction are currently underway in our laboratory.

Methods

Generation and Stark deceleration of OH radicals

Prior to trapping, the density of OH radicals after the decelerator was optimised as outlined in58. In brief, the process involved optimising the coupling of the molecular beam into the Stark decelerator and the discharge settings for achieving maximum OH densities in the source region. After the dissociation of H2O into OH radicals, the mean velocity of the molecular beam was found to be v = 425 m/s with a velocity spread Δv/v of 13% (FWHM). In a subsequent step, the molecular beam was coupled into the decelerator by adjusting the incoupling time, i.e. the time required for the molecules to reach the entrance of the Stark decelerator from their point of generation. The sequence of high voltage pulses applied to the deceleration electrodes is automatically calculated to reach the desired final velocity. TOF profiles were acquired by monitoring the LIF signal intensity as a function of the time delay at the position of the trap centre 11.5 mm downstream from the exit of the Stark decelerator, 894 mm from the source.

LIF detection of OH molecules

The presence of OH molecules in the trap region was verified and quantified by collecting LIF photons from electronically excited OH radicals. A frequency-doubled Rhodamine 6G dye laser (Pulsare, Fine Adjustment) was pumped by the second harmonic (532 nm) of a Nd:YAG laser (Surelite II, Continuum) to generate laser radiation at 282 nm. The laser beam was passed through a pinhole (∅ = 10 μm) to filter out higher-order transverse laser modes and was telescoped to a 1/e2-radius of 0.8 mm in front of the vacuum chamber. The 282 nm laser radiation excited OH molecules from their X 2Π(v = 0) ground vibronic state to the A 2Σ(v = 1) excited vibronic state under saturation conditions. The excited state predominantly relaxes via the A2Π(v = 1) − X2Π(v = 1) transition under the emission of fluorescence at 313 nm. The fluorescence was collected by a UV-grade lens to be detected by a calibrated photomultiplier tube (B2/RFI 9813 QB, C638AFN1, Electron Tubes). Stray light suppression was achieved by inserting narrow band-pass filters (FF01-315, Semrock and XHQA313, Asahi Spectra) in front of the PMT. Digitised, averaged LIF traces at a specific laser delay were integrated over a specified time window of 2.13 μs yielding the individual points of the shown TOF and trapping profiles.

Trap loading

To load the decelerated molecules into the trap, the electric potentials as shown in Fig. 3 were switched using two fast MOSFET push-pull switches (HTS 301-03-GSM, HFB, Behlke Power Electronics) backed by two 0.5 μF capacitors (PPR200-504, Hivolt Capacitors Ltd.). The onset and the duration of the stopping fields were optimised for maximum LIF signal.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer codes used for the simulations in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Carr, L. D., DeMille, D., Krems, R. V. & Ye, J. Cold and ultracold molecules: science; technology and applications. New J. Phys. 11, 055049 (2009).

van de Meerakker, S. Y. T., Bethlem, H. L., Vanhaecke, N. & Meijer, G. Manipulation and control of molecular beams. Chem. Rev. 112, 4828–4878 (2012).

Willitsch, S. Coulomb-crystallised molecular ions in traps: methods, applications, prospects. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 31, 175–199 (2012).

Lemeshko, M., Krems, R. V., Doyle, J. M. & Kais, S. Manipulation of molecules with electromagnetic fields. Mol. Phys. 111, 1648–1682 (2013).

Moses, S. A., Covey, J. P., Miecnikowski, M. T., Jin, D. S. & Ye, J. New frontiers for quantum gases of polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 13, 13–20 (2017).

Willitsch, S. Chemistry with controlled ions. Adv. Chem. Phys. 162, 307–340 (2017).

Wall, T. E. Preparation of cold molecules for high-precision measurements. J. Phys. B 49, 243001 (2016).

Borri, S. & Santambrogio, G. Laser spectroscopy of cold molecules. Adv. Phys.: X 1, 368–386 (2016).

Bohn, J. L., Rey, A. M. & Ye, J. Cold molecules: progress in quantum engineering of chemistry and quantum matter. Science 357, 1002–1010 (2017).

Safronova, M. S. et al. Search for new physics with atoms and molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 025008 (2018).

Hudson, E. R., Lewandowski, H. J., Sawyer, B. C. & Ye, J. Cold molecule spectroscopy for constraining the evolution of the fine structure constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 143004 (2006).

Bethlem, H. L., Kajita, M., Sartakov, B., Meijer, G. & Ubachs, W. Prospects for precision measurements on ammonia molecules in a fountain. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 163, 55–69 (2008).

Bethlem, H. L. & Ubachs, W. Testing the time-invariance of fundamental constants using microwave spectroscopy on cold diatomic radicals. Faraday Discuss. 142, 25–36 (2009).

Truppe, S. et al. A search for varying fundamental constants using hertz-level frequency measurements of cold CH molecules. Nat. Commun. 4, 2600 (2013).

Baron, J. et al. Order of magnitude smaller limit on the electric dipole moment of the electron. Science 343, 269–272 (2014).

Kozyryev, I. et al. Sisyphus laser cooling of a polyatomic molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 173201 (2017).

Lim, J. et al. Laser cooled YbF molecules for measuring the electron’s electric dipole moment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 123201 (2018).

Willitsch, S., Bell, M. T., Gingell, A. D., Procter, S. R. & Softley, T. P. Cold reactive collisions between laser-cooled ions and velocity-selected neutral molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 043203 (2008).

Ospelkaus, S. et al. Quantum-state controlled chemical reactions of ultracold potassium-rubidium molecules. Science 327, 853–857 (2010).

Hall, F. & Willitsch, S. Millikelvin reactive collisions between sympathetically cooled molecular ions and laser-cooled atoms in an ion-atom hybrid trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 233202 (2012).

Yan, B. et al. Observation of dipolar spin-exchange interactions with lattice-confined polar molecules. Nature 501, 521–525 (2013).

Chefdeville, S. et al. Observation of partial wave resonances in low-energy O2–H2 inelastic collisions. Science 341, 1094–1096 (2013).

Vogels, S. N. et al. Imaging resonances in low-energy NO-He inelastic collisions. Science 350, 787–790 (2015).

Wu, X. et al. A cryofuge for cold-collision experiments with slow polar molecules. Science 358, 645–648 (2017).

Vogels, S. N. et al. Scattering resonances in bimolecular collisions between NO radicals and H2 challenge the theoretical gold standard. Nat. Chem. 10, 435–440 (2018).

Parazzoli, L. P., Fitch, N. J., Żuchowski, P. S., Hutson, J. M. & Lewandowski, H. J. Large effects of electric fields on atom-molecule collisions at millikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 193201 (2011).

Micheli, A., Brennen, G. K. & Zoller, P. A toolbox for lattice-spin models with polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 2, 341–347 (2006).

Blackmore, J. A. et al. Ultracold molecules for quantum simulation: rotational coherences in CaF and RbCs. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4, 014010 (2018).

DeMille, D. Quantum computation with trapped polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 067901 (2002).

Yelin, S. F., Kirby, K. & Côté, R. Schemes for robust quantum computation with polar molecules. Phys. Rev. A 74, 050301 (2006).

van de Meerakker, S. Y. T., Smeets, P. H. M., Vanhaecke, N., Jongma, R. T. & Meijer, G. Deceleration and electrostatic trapping of OH radicals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 023004 (2005).

Quintero-Pérez, M. et al. Static trapping of polar molecules in a traveling wave decelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 133003 (2013).

Hoekstra, S. et al. Optical pumping of trapped neutral molecules by blackbody radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 133001 (2007).

Englert, B. G. U. et al. Storage and adiabatic cooling of polar molecules in a microstructured trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 263003 (2011).

Seiler, C., Hogan, S. D. & Merkt, F. Trapping cold molecular hydrogen. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 19000–19012 (2011).

Zeppenfeld, M. et al. Sisyphus cooling of electrically trapped polyatomic molecules. Nature 491, 570–573 (2012).

Prehn, A., Ibrügger, M., Glöckner, R., Rempe, G. & Zeppenfeld, M. Optoelectrical cooling of polar molecules to submillikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 063005 (2016).

Lu, H.-I., Kozyryev, I., Hemmerling, B., Piskorski, J. & Doyle, J. M. Magnetic trapping of molecules via optical loading and magnetic slowing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 113006 (2014).

Weinstein, J. D., de Carvalho, R., Guillet, T., Friedrich, B. & Doyle, J. M. Magnetic trapping of calcium monohydride molecules at millikelvin temperature. Nature 395, 148–150 (1998).

Eardley, J. S. et al. Magnetic trapping of SH radicals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 8423–8427 (2017).

Liu, Y., Zhou, S., Zhong, W., Djuricanin, P. & Momose, T. One-dimensional confinement of magnetically decelerated supersonic beams of O2 molecules. Phys. Rev. A 91, 021403 (2015).

Sawyer, B. C. et al. Magnetoelectrostatic trapping of ground state OH molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 253002 (2007).

Liu, Y. et al. Magnetic trapping of cold methyl radicals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 093201 (2017).

Akerman, N. et al. Trapping of molecular oxygen together with lithium atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 073204 (2017).

McCarron, D. J., Steinecker, M. H., Zhu, Y. & DeMille, D. Magnetic trapping of an ultracold gas of polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 013202 (2018).

Williams, H. J. et al. Magnetic trapping and coherent control of laser-cooled molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 163201 (2018).

Riedel, J. et al. Accumulation of stark-decelerated NH molecules in a magnetic trap. Eur. Phys. J. D. 65, 161–166 (2011).

Segev, Y. et al. Collisions between cold molecules in a superconducting magnetic trap. 2019. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.04549.

Takekoshi, T., Patterson, B. M. & Knize, R. J. Observation of optically trapped cold cesium molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5105–5108 (1998).

Ni, K.-K. et al. A high phase-space-density gas of polar molecules. Science 322, 231–235 (2008).

Hummon, M. T. et al. 2D magneto-optical trapping of diatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 143001 (2013).

Barry, J., McCarron, D., Norrgard, E., Steinecker, M. & DeMille, D. Magneto-optical trapping of a diatomic molecule. Nature 512, 286–289 (2014).

Tsikata, E., Campbell, W. C., Hummon, M. T., Lu, H.-I. & Doyle, J. M. Magnetic trapping of NH molecules with 20s lifetimes. New J. Phys. 12, 065028 (2010).

Wieman, C. E., Pritchard, D. E. & Wineland, D. J. Atom cooling; trapping; and quantum manipulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, S253–S262 (1999).

Janssen, L. M. C., van der Avoird, A. & Groenenboom, G. C. Quantum reactive scattering of ultracold NH X 3∑− radicals in a magnetic trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 063201 (2013).

Häffner, H., Roos, C. F. & Blatt, R. Quantum computing with trapped ions. Phys. Rep. 469, 155–203 (2008).

Ploenes, L., Haas, D., Zhang, D., van de Meerakker, S. Y. T. & Willitsch, S. Cold and intense OH radical beam sources. Rev. Sci. Instr. 87, 053305 (2016).

Haas, D., Scherb, S., Zhang, D. & Willitsch, S. Optimizing the density of Stark decelerated radicals at low final velocities: a tutorial review. EPJ Tech. Instrum. 4, 6 (2017).

Sawyer, B. C., Stuhl, B. K., Wang, D., Yeo, M. & Ye, J. Molecular beam collisions with a magnetically trapped target. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 203203 (2008).

Rennick, C. J., Lam, J., Doherty, W. G. & Softley, T. P. Magnetic trapping of cold bromine atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 023002 (2014).

García, L. M., Bartolomé, F. & Goedkoop, J. B. Orbital magnetic moment instability at the spin reorientation transition of Nd2Fe14B. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 429 (2000).

Börgermann, F.-J., Brombacher, C. & Üstüner, K. Properties, options and limitations of PrFeB-magnets for cryogenic undulators. Proceedings of IPAC2014 1238–1240 (Dresden, Germany, 2014).

Abramson, M. et al. The NOMAD project: Software. https://www.gerad.ca/nomad/ (2019).

Le Digabel, S. Nomad: nonlinear optimization with the mads algorithm. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 37, 44:1–44:15 (2011).

Lara, M., Lev, B. L. & Bohn, J. L. Loss of molecules in magneto-electrostatic traps due to nonadiabatic transitions. Phys. Rev. A 78, 033433 (2008).

Reens, D., Wu, H., Langen, T. & Ye, J. Controlling spin flips of molecules in an electromagnetic trap. Phys. Rev. A 96, 063420 (2017).

Stuhl, B. K. et al. Evaporative cooling of the dipolar hydroxyl radical. Nature 492, 396–400 (2012).

Stuhl, B. K., Yeo, M., Hummon, M. T. & Ye, J. Electric-field-induced inelastic collisions between magnetically trapped hydroxyl radicals. Mol. Phys. 111, 1798–1804 (2013).

Quéméner, G. & Bohn, J. L. Ultracold molecular collisions in combined electric and magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. A 88, 012706 (2013).

Willitsch, S. Ion-atom hybrid systems. Proc. Int. Sch. Phys. Enrico Fermi 189, 255–268 (2015).

Acknowledgements

D.Z. acknowledges the financial support from Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel and the Research Fund for Junior Researchers of the University of Basel. We thank Prof. Sebastiaan Y.T. van de Meerakker (Radboud University) for helpful discussions. This project is funded by the Swiss National Sciene Foundation, grant no. 200020_175533, and the University of Basel. We would like to thank P. Knöpfel, G. Martin and G. Holderied from the departmental workshops for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.H., C.P., T.K. and D.Z. conducted the experiments and analysed the data. S.W. conceived and D.Z. and S.W. supervised the project. D.H. designed and optimised the trap loading process based on trajectory simulations. C.P. calculated the BBR and background collision limited trapping lifetime and implemented the cryogenic trap. All authors participated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haas, D., von Planta, C., Kierspel, T. et al. Long-term trapping of Stark-decelerated molecules. Commun Phys 2, 101 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0199-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0199-4

- Springer Nature Limited