Abstract

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) from Option B plus, a lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) for pregnant women living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), irrespective of their clinical stage and CD4 count, threatens the elimination of vertical transmission of the virus from mothers to their infants. However, evidence on reasons for LTFU and resumption after LTFU to Option B plus care among women has been limited in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study explored why women were LTFU from the service and what made them resume or refuse resumption after LTFU in Ethiopia. An exploratory, descriptive qualitative study using 46 in-depth interviews was employed among purposely selected women who were lost from Option B plus care or resumed care after LTFU, health care providers, and mother support group (MSG) members working in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission unit. A thematic analysis using an inductive approach was used to analyze the data and build subthemes and themes. Open Code Version 4.03 software assists in data management, from open coding to developing themes and sub-themes. We found that low socioeconomic status, poor relationship with husband and/or family, lack of support from partners, family members, or government, HIV-related stigma, and discrimination, lack of awareness on HIV treatment and perceived drug side effects, religious belief, shortage of drug supply, inadequate service access, and fear of confidentiality breach by healthcare workers were major reasons for LTFU. Healthcare workers' dedication to tracing lost women, partner encouragement, and feeling sick prompted women to resume care after LTFU. This study highlighted financial burdens, partner violence, and societal and health service-related factors discouraged compliance to retention among women in Option B plus care in Ethiopia. Women's empowerment and partner engagement were of vital importance to retain them in care and eliminate vertical transmission of the virus among infants born to HIV-positive women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Lost to follow-up is a major challenge in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV among HIV-exposed infants (HEI). Globally, about 1.5 million children under 15 years old were living with HIV, and 130,000 acquired the virus in 20221. In the African region, an estimated 1.3 million children aged 0–14 were living with HIV at the end of 2022, and 109,000 children were newly infected2. Five out of six paediatric HIV infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa in 20223. Most of these infections are due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT), accounting for around 90% of all new infections4,5. Without any intervention, between 15 and 45 percent of infants born to HIV-positive mothers are likely to acquire the virus from their mothers, with half dying before their second birthday without treatment3. Almost 70% of new HIV infections were due to mothers not receiving ART or dropping off during pregnancy or breastfeeding3.

In Ethiopia, the burden of MTCT of HIV is high, with a pooled prevalence ranging from 5.6% to 11.4%6,7,8,9,10. Ethiopia adopted the 2013 World Health Organization’s Option B plus recommendations as the preferred strategy for the PMTCT of HIV in 201311,12,13,14. Accordingly, a combination of triple antiretroviral (ARV) drugs was provided for all HIV-infected pregnant and/or breastfeeding women, irrespective of their CD4 count and World Health Organization (WHO) clinical staging11,13. Besides, the drug type was switched from an EFV-based to a DTG-based regimen to enhance maternal life quality and decrease LTFU from Option B plus care11,15. The Efavirenz-based regimen consists of Tenofovir (TDF), Lamivudine (3TC), and Efavirenz (EFV), while the DTG-based regimen consists of TDF, 3TC, and DTG13,15,16. The change in regimen was due to better tolerability and rapid viral suppression, thereby retaining women in care and achieving MTCT of HIV targets17,18.

The trend of women accessing ART for PMTCT services increases, and new HIV infections decrease over time3,19,20. However, the effectiveness of Option B plus depends not only on service coverage but also on drug adherence and retention in care4,15,21. In this regard, quantitative studies conducted in Ethiopia showed that the prevalence of LTFU from Option B plus ranged from 4.2% to 18.2%22,23,24. Besides, the overall incidence of LTFU ranged from 9 to 9.4 per 1000 person-months of observation25,26, which is a challenge for the success of the program.

Qualitative studies also revealed that the main reasons for LTFU among women were maternal educational status, drug side effects, lack of partner and family support, lack of HIV status disclosure, poverty, discordant HIV test results, religious belief, stigma, and discrimination, long distance to the health facility, and history of poor adherence to ART27,28,29,30,31,32. Reasons for resumption to care were a decline in health status, a desire to have an uninfected child, and support from others30,33. Unless the above risk factors for LTFU are managed, the national plan to eliminate the MTCT of HIV by 2025 will not be achieved34.

Currently, because of its fewer side effects and better tolerability, a Dolutegravir (DTG)-based regimen is given as a preferred first-line regimen to pregnant and/or breastfeeding women to reduce the risk of LTFU13,16. The goal is to reduce new HIV transmissions and achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.3 of ending Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) as a public health threat by 203035,36,37. As mentioned above, there is rich information on the prevalence and risk factors of LTFU among women on Option B plus care before the DTG-based regimen was implemented. Besides, the previous qualitative studies addressed the reasons for LTFU from providers’ and/or women’s perspectives rather than including mother support group (MSG) members. However, there was a lack of evidence that explored the reasons for LTFU and resumption of care after LTFU from the perspectives of MSG members, lost women, and healthcare workers (HCWs) providing care to women. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the reasons why women LTFU and resumed Option B plus care after the implementation of a DTG-based regimen in Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

An exploratory, descriptive qualitative study38 was conducted between June and October 2023. This study was conducted in two regions of Ethiopia: Central Ethiopia and South Ethiopia. These neighbouring regions were formed on August 19, 2023, after the disintegration of the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region after a successful referendum39. The authors included these nearby regions to get an adequate sample size and cover a wider geographic area. In these regions, 140 health facilities (49 hospitals and 91 health centers) provided PMTCT and ART services to 28,885 patients at the time of the study, of whom 1,236 were pregnant or breastfeeding women (675 in South Ethiopia and 561 in Central Ethiopia).

Participants and data collection

Study participants were women who were lost from PMTCT care or resumed PMTCT care after LTFU, MSG members, and HCWs provided PMTCT care. Mother support group members were HIV-positive women working in the PMTCT unit to share experiences and provide counselling services on breastfeeding, retention, and adherence, and to trace women when they lost Option B plus care11,40. Healthcare workers were nurses or midwives working in the PMTCT unit to deliver services to women enrolled in Option B plus care.

Purposive criterion sampling was employed to select study participants from twenty-one facilities (nine health centers and twelve hospitals) providing PMTCT service. A total of 46 participants were included in the study. The interview included 15 women (eleven lost and four resumed care after LTFU), 14 providers, and 17 MSG members. Healthcare workers and MSG members were chosen based on the length of time they spent engaging with women on Option B plus care; the higher the work experience, the more they were selected to get adequate information about the study participants. Including the study participants in each group continued until data saturation.

The principal investigator, with the help of HCWs and MSG members, identified lost women from the PMTCT registration books and appointment cards. A woman's status was recorded as LTFU if she missed the last clinic appointment for at least 28 days without documented death or transfer out to another facility15. Providers contacted women based on their addresses recorded during enrolment in Option B plus care, either via phone (if functional) or by conducting home visits for those unable to be reached. Informed written consent was obtained, and the research assistants conducted in-depth interviews at women’s homes or health facilities based on their preferences. After an interview, eleven women who lost care were counselled to resume PMTCT care, but nine returned to care and two refused to resume care. Besides, the principal investigator, HCWs, and MSG members identified women who resumed care after LTFU, called them via phone to visit the health facility at their convenience, and conducted the interview after obtaining consent. The research team covered transportation costs and provided adherence counselling to women post-interview. A woman resumed care if she came back to PMTCT care on her own or healthcare workers’ efforts after LTFU.

One-on-one, in-depth interviews were conducted with eligible MSG members and HCWs at respective health facilities. A semi-structured interview guide translated into the local language (Amharic) was used to collect data. The guide comprises the following constructs: why women are lost to follow-up from PMTCT care, what made them resume caring after LTFU, and why they did not resume Option B plus care after LTFU with probing questions (Supplementary File 1). The interview was conducted for 18 to 37 min with each participant, and the duration was communicated to study participants before the interview. The interview was audio-taped, and field notes were taken during the interviews.

Data management and analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data. The research assistants transcribed the interviews verbatim within 48 h of data collection and translated them from the local language (Amharic) to English for analysis. The principal investigator read the translated document several times to get a general sense of the content. An inductive approach was applied to allow the conceptual clustering of ideas and patterns to emerge. The authors preferred an inductive approach to analyze data since there were no pre-determined categories. The core meaning of the phrases and sentences relevant to the research aim was searched. Codes were assigned to the phrases and sentences in the transcript, which were later used to develop themes and subthemes. The subthemes were substantiated by quotes from the interviews. The interviews developed two themes: reasons for LTFU and the reasons for resumption after LTFU. The findings were triangulated from healthcare workers, MSG members, and client responses. Open code software version 4.03 was used to assist in data management, from open coding to the development themes and sub-themes.

Results

Background characteristics of the study participants

We successfully interviewed 46 participants (14 providers, 15 women, and 17 MSG members) until data saturation. The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) of age was 25.53 (± 0.99) years for women, 32.5 (± 1.05) years for MSG members, and 32.2 (± 1.05) years for care providers. Three out of fifteen women did not disclose their HIV status to their partner, and 5/15 women’s partners were discordant. The mean (± SD) service years in the PMTCT unit were 10.3 (± 1.3) for MSG members and 3.29 (± 0.42) for care providers (Supplementary File 2).

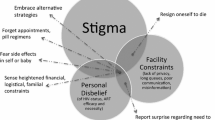

Reasons for LTFU

Women who started ART to prevent MTCT of HIV were lost from care due to different reasons. Societal and individual-related factors and health facility-related factors were the two main dimensions that made women LTFU. The societal and individual-related factors were socioeconomic status, relations with husbands or families, lack of support, HIV-related stigma and discrimination, lack of awareness and perceived antiretroviral (ARV) side effects, and religious belief. Health facility-related factors such as lack of confidentiality, drug supply shortages, and inadequate service access led to women's loss from Option B plus care (Supplementary File 3).

Societal and individual-related factors

Socioeconomic status

Lack of money to buy food was a major identified problem for women’s LTFU. Women who did not have adequate food to eat became undernourished, which significantly increased the risk of LTFU. Besides, they did not want to swallow ARV drugs with an empty stomach and thus did not visit health facilities to collect their drugs.

“My life is miserable. I have nothing to eat at my home. How would I take the drug on an empty stomach? Let the disease kill me rather than die due to hunger. This is why I stopped to take the medicine and LTFU.” (W-02, 30-year-old woman, divorced, daily labourer)

Women also disappeared from PMTCT care due to a lack of money to cover transportation costs to reach health facilities.

I need a lot of money to pay for transportation that I can’t afford. Sometimes I came to the hospital borrowing money for transportation. It is challenging to attend a follow-up schedule regularly to collect ART medications.” (W-11, 26-year-old woman, married, housewife)

Relationships with husbands and/or families

Fear of violence and divorce by sexual partners were identified as major reasons for the LTFU of women from PMTCT care. Due to fear of partner violence and divorce, women did not want to be seen by their partners while visiting health facilities for Option B plus care and swallowing ARV drugs. As a result, they missed clinic appointments, did not swallow the drugs, and consequently lost care.

“Due to discordant test results, my husband divorced me. Then I went to my mother's home with my child. I haven’t returned to take the drug since then and have lost PMTCT care.” (W-03, 25-year-old woman, divorced, commercial sex worker)

Women did not disclose their HIV status to their discordant sexual partners and family members due to fear of stigma and discrimination. As a result, they did not swallow drugs in front of others and were unable to collect the drugs from health facilities.

“I know a mother who picked up her drugs on market day as if she came to the market to buy goods. No one knows her status. She hides the drug and swallows it when her husband sleeps.” (P-05, 29-year-old provider, female, 3 years of experience in the PMTCT unit)

“I don't want to be seen at the ART unit. I have no reason to convince the discordant husband to visit a health facility after delivery. My husband kills me if he knows that I am living with HIV. This is why I discontinued the care.” (W-12, 18-year-old woman, married, housewife)

Women who lack partner support in caring for children at home during visits to health facilities find it difficult to adhere to clinic visits. Besides, women who did not get financial and psychological support from their partners faced difficulties in retaining care.

“Taking care of children is not business for my husband. How could I leave my two children alone at home? Or can I bring them biting with my teeth?” (W-05, 24-year-old woman, divorced, daily labourer)

“I didn't get any financial or psychological support from my husband. This made me drop PMTCT care.” (W-15, 34-year-old woman, married, daily labourer)

Lack of support

Women living with HIV also had complaints of lack of support from the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and HIV-related associations in cash and in kind. As a result, they were disappointed to remain in care.

"Previously, we got financial and material support from NGOs. Besides, the government arranged places for material production and goods sale to improve our economic status. However, now we didn't get any support from anywhere. This made our lives hectic to retain PMTCT care.” (W-06, 29-year-old woman, married, daily labourer)

HIV-related stigma and discrimination

Fear of stigma and discrimination by sexual partners, family members, and the community were mentioned as reasons for LTFU. Gossip, isolation, and rejection from societal activities were the dominant stigma experiences the women encountered. As a result, they did not want to be seen by others who knew them while collecting ARV drugs from health facilities, and consequently, they were lost from care and treatment.

“Despite getting PMTCT service at the nearby facility, some women come to our hospital traveling long distances. They don't want to be seen by others while taking ARV drugs there due to fear of stigma and discrimination by the community.” (P-10, 34-year-old provider, female, 2 years of experience in the PMTCT unit)

“I am a daily labourer and bake ‘injera’ (a favourite food in Ethiopia) at someone's house to run my life. If the owner knew my status, I am sure she would not allow me to continue the job. In that case, what would I give my child to eat?” (W-12, 18-year-old woman, married, housewife)

“My family did not know that I was living with the virus. If they knew it, I am sure they would not allow me to contact them during any events. Thus, I am afraid of telling them that I had the virus in my blood.” (W-05, 24-year-old woman, divorced, daily labourer)

Lack of awareness and perceived ARV side effects

Sometimes women went to another area for different reasons without taking ARV drugs with them. As per the Ethiopian national treatment guidelines13, they could get the drugs temporarily from any nearby facility that delivers PMTCT service. However, those who did not know that they could get the drugs from other nearby PMTCT facilities lost their care until their return. Others were lost, considering that ARV drugs harm the health status of their babies.

“One mother refused to retain in care after the delivery of a congenitally malformed baby (no hands at birth). She said, 'This abnormal child was born due to the drug I was taking for HIV. I delivered two healthy children before taking this medication. I don't want to re-use the drug that made me give birth to a malformed baby." (P-14, 32-year-old provider, female, 4 years of experience in the PMTCT unit)

When they did not encounter any health problems, women were lost from care, considering that they had become healthy and not in need of ART. Some of them also believe that having HIV is a result of sin, not a disease. Besides, some women believed that it was not possible to have a discordant test result with their partner.

“I didn't commit any sexual practice other than with my husband. His test result is negative. So, from where did I get the virus? I don't want to take the drug again.” (W-02, 30-year-old woman, divorced, daily labourer)

Religious belief

Some study participants mentioned religious belief as a reason for LTFU and a barrier to resumption after LTFU. Women discontinued Option B plus care due to their religious faith and refused to resume care as they were cured by the Holy Water and prayer by religious leaders.

“I went to Holy Water and was there for two months. My health status resumed due to prayer by monks and priests there. Despite not taking the drugs during my stay, God cured me of this evil disease with Holy Water. Now I am healthy, and there is no need to take the medicine again.” (W-09, 25-year-old woman, married, daily labourer)

Some women believed that God cured them and made their children free of the virus despite not taking ART for themselves and not giving ARV prophylaxis for their infants.

“Don't raise this issue again (when MSG asked to resume PMTCT care). I don't want to use the medicine. I am cured of the disease by the word of God, and my child is too. My God did not lie in His word.” (MSG-16, 32-year-old MSG, married, 16 years of service experience

“Don't come to my home again. I don't have the virus now. I have been praying for it, and God cured me.” (W-03, 25-year-old woman, divorced, commercial sex worker)

Health facility-related factors

Shortage of drug supply

Women were not provided with all HIV-related services free of charge and were required to pay for therapeutic and prophylactic drugs for themselves and their infants. Most facilities face a shortage of prophylactic drugs, primarily cotrimoxazole and nevirapine syrups, for infants and women, and other drugs used to treat opportunistic infections. As a result, women lost their PMTCT care when told to buy prophylactic syrups for infants and therapeutic drugs to treat opportunistic infections for themselves.

“Lack of cotrimoxazole syrup is one of the major reasons for women to miss PMTCT clinic visits. In our facility, it was out of stock for the last three months. Women can't afford its cost due to their economic problems.” (MSG-03, 34-year-old provider, married, 12 years of service experience)

Inadequate service access

Most women travelled long distances to reach health facilities to get PMTCT service due to the absence of a PMTCT site in their area. Due to a lack of transportation access and/or cost, they were forced to miss clinic visits for PMTCT care.

“In this district, there were only two PMTCT sites. Women travelled long distances to get the service. To reach our facility, they must travel half a day or pay more than three hundred Ethiopian birr for a motorbike that some cannot afford. Thus, women lost the service due to inadequate service access.” (P-06, 30-year-old provider, male, 2 years of experience in the PMTCT unit)

In almost all facilities, PMTCT service was not given on weekends and holidays, despite women's interest in being served at these times. When ARV drugs were stocked out at their homes, they did not get the drugs if facilities were not providing services on weekends and holidays. When appointment date was passed, they lost care due to fear of health workers’ reactions.

Lack of confidentiality

Despite maintaining ethical principles to retain women in care, breaches of confidentiality by HCWs were one of the reasons for LTFU by women. Women were afraid of meeting someone they knew or that their privacy would not be respected. As a result, they lost from PMTCT care.

“I don’t want to visit the facility. All my information was distributed to the community by a HCW who counselled me at the antenatal clinic.” (W-09, 25-year-old woman, married, daily labourer)

Reasons for resumption after LTFU

Healthcare workers' commitment to searching for lost women, partners’ encouragement, and women’s health status were key reasons for resuming women's Option B plus services after LTFU.

Healthcare workers’ commitment

The majority of lost women resumed Option B plus care after LTFU when healthcare workers called them via phone or conducted home visits for those who could not be reached by phone call.

“We went to a woman’s home, who started ART during delivery and lost for four months, travelling about 90 kilometers. She just cried when she saw us. She said, 'As long as you sacrificed your time traveling such a long distance to return me and save my life, I will never disappear from care today onward.' Then, she returned immediately and was linked to the ART unit after completing her PMTCT program.” (P-13, 32-year-old provider, male, 5 years of experience in the PMTCT unit)

“We have an appointment date registry for every woman. We waited for them for seven days after they failed to arrive on the scheduled appointment date. From the 8th day onward, we called them via phone if it was available and functional. If we didn't find them via phone, we conducted home visits and returned them to care.” (P-02, 24-year-old provider, female, 3 years of experience in the PMTCT unit)

Partner encouragement

Women who got their partners' encouragement did not drop out of PMTCT care. Besides, most women returned to care and restarted their ARV drugs due to partner encouragement.

“I did not disclose my HIV status to my husband, which was diagnosed during the antenatal period. I lost my care after the delivery of a male baby. When my husband knew my status, rather than disagreeing, he encouraged me to resume the care to live healthily and to prevent the transmission of HIV to our baby. This was why I resumed care after LTFU.” (W-14, 28-year-old woman, divorced, daily labourer)

Women’s health status

Some women returned to Option B plus care on their own when they felt sick and wanted to stay healthy.

“When I felt healthy, I was away from care for about eight months. Later on, when I sought medical care for the illness, doctors gave me medicine and linked me to this unit (the PMTCT unit). I returned because of sickness.” (W-06, 29-year-old woman, married, daily labourer)

Discussion

This qualitative study assessed the reasons why women left the service and why they resumed care after LTFU. The study aimed to enhance program implementation by providing insights into reasons for LTFU and facilitators for resumption from women's, health professionals', and MSG members' perspectives. We found that financial problems, partner violence, lack of support, HIV-related stigma and discrimination, lack of awareness, religious belief, shortage of drug supply, poor access to health services, and fear of confidentiality breaches by healthcare providers were major reasons for LTFU from PMTCT care. Healthcare workers’ commitment, partner encouragement, and feeling sick made women resume PMTCT care after LTFU.

In this study, fear of partner violence and divorce were identified as major reasons that made women discontinue the PMTCT service. Men are the primary decision-makers regarding healthcare service utilization, and the lack of male involvement in the continuity of PMTCT care decreases maternal health service utilization, including PMTCT services41,42. In addition, economic dependence on men threatened women not to adhere to clinic appointments without their partner’s willingness due to fear of violence and divorce28. Thus, strengthening couple counselling and testing13, male involvement in maternal health services, and women empowerment strategies like promoting education, property ownership, and authority sharing to reach decisions on health service utilization were crucial to retaining women in PMTCT care. Besides, legal authorities and community and religious leaders should be involved in preventing domestic violence and raising awareness about the negative effects of divorce on child health.

Financial constraints to cover daily expenses were major reasons expressed by women for LTFU from PMTCT care. Consistent with other studies, this study revealed that a lack of money to cover transportation costs resulted in poor adherence to ART and subsequent loss of PMTCT care27,29,43. As evidenced by other studies, lack of food resulting from financial problems was a major reason for LTFU in the study area30. As a result, women prefer death to living with hunger due to food scarcity, which led them to LTFU. Besides, women of poor economic status spent more time on jobs to get money to cover day-to-day expenses than thinking of appointment dates. Thus, governments and organizations working on HIV prevention programs should strengthen economic empowerment programs like arranging loans to start businesses and creating job opportunities for women living with HIV.

Despite continuous information dissemination via different media, fear of stigma and discrimination was a frequently reported reason for LTFU among women in PMTCT care. Consistent with other studies conducted in Ethiopia and other African countries, our study identified that fear of stigma and discrimination by partners, family, and community members are significant risk factors for LTFU27,28,29,31. As a result, women did not usually disclose their HIV status to their partners28,32 so that they could not get financial and psychological support. This highlights the need to intensify interventions by different stakeholders to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination in the study area. Women's associations, community-based organizations, and religious, community, and political leaders should continuously work on advocacy and awareness creation to combat HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

Our study revealed that a lack of support for women made them discontinue life-saving ARV drugs. In developing countries like Ethiopia, most women living with HIV have low socio-economic status to run their lives, and thus they need support. However, as claimed by the majority of study participants, the government and organizations working on HIV programs were decreasing support from time to time. This was in line with qualitative studies such that lack of support by family members or partners27 was identified as a barrier to adherence to and retention in PMTCT care27,28,29,30,32. Organizations working on HIV programs need to design strategies so that poor women get support from partners, family members, the community, religious leaders, and the government to stay in PMTCT care. Moreover, some women thought incentives and support must be given to retain them in Option B plus care. Thus, HCWs should inform women during counselling sessions that they should not link getting PMTCT care to incentives or support.

Women infected with HIV want to be healthy and have HIV-free infants, which could be achieved by proper utilization of recommended therapy as per the protocol27,43. However, women’s religious beliefs were found to interfere with adherence to the recommended treatment protocol, made them LTFU, and refused resumption after LTFU. Although religious belief did not oppose the use of ARV drugs at any time, women did not take the medicine when they went to Holy Water and prayer. As evidenced by previous studies, lost women perceived that they were cured of the disease with the help of God and refused to resume PMTCT care27,30. This finding suggests the need for sustained community sensitization about HIV and its treatment, engaging religious leaders. They need to inform women on ART that taking ARV drugs does not contradict religious preaching, and they should not discontinue the drug at any religious engagement.

Once on ART, women should not regress from care and treatment due to problems related to the facility. Unlike the study conducted in Malawi, which reported a shortage of drugs as not a cause of LTFU29, in the study area there was a shortage of drugs and supplies to give appropriate care to women and their infants and to retain them in care. They did not get all services related to HIV free of charge and were requested to pay for them, including the cotrimoxazole syrup given to their infants. The finding was consistent with the study conducted in Malawi, where the irregular availability of cotrimoxazole syrup was mentioned as a risk factor for LTFU32.

On some occasions, there may also be a shortage of ARV prophylaxis (Nevirapine and Zidovudine syrups) at some facilities for their infants that they couldn’t get from private pharmacies. Services related to PMTCT care were expected to be free of charge for mothers and their infants throughout the care. Ensuring an adequate supply of prophylactic and therapeutic drugs should be considered to prevent the MTCT of HIV and control the spread of the disease among communities via appropriate resource allocation. Facilities should have an adequate supply of ARV prophylaxis and should not request that women pay for diagnostic services. Besides, they always need to provide cotrimoxazole syrup free of charge for HIV-exposed infants.

Lack of awareness of a continuum of PMTCT care among women is a major challenge to retaining them in care. Women who experienced malpractice against standard care practice and had misconceptions about the disease were at higher risk for LTFU. Those women who forgot to take ARV drugs due to different reasons (maybe due to poor counselling) did not get the benefits of ART. Improved counselling and appropriate patient-provider interaction increase women’s engagement in care and reduce the risk of LTFU28,44. Thus, proper counselling on adherence, malpractice, and misconceptions should be strengthened by healthcare providers in PMTCT units to create optimal awareness for retention.

Maintaining clients’ confidentiality is the backbone of achieving HIV-related treatment goals. However, some women disappear from PMTCT care due to a lack of confidentiality by HCWs delivering the service. Although not large, women claimed a lack of privacy during counselling, and disclosing their HIV status in the community was practiced by some healthcare professionals. The finding was consistent with the study conducted in developing countries, including Ethiopia, where lack of privacy and fear regarding breaches of confidentiality by healthcare workers were identified as risk factors for LTFU31,32,44. Thus, HCWs should deliver appropriate counselling services and maintain clients’ confidentiality to develop trust among women.

The validity of the findings of this study was strengthened by the triangulating data collected from women, MSG members, and HCWs delivering PMTCT service. Besides, the study included women from the community who had already been lost from care during the study, which minimized the risk of recall bias. However, we recognized the following limitations. First, the study did not explore the husband’s perspective to validate the findings from women and HCWs. Second, the study may have different reasons for LTFU for women who were unreached or unwilling to participate compared to those who agreed to be interviewed. Thus, further studies are advised to include the husband’s perception to validate their concern and to address all women who have lost care.

Conclusions

Financial constraints to cover transportation costs, fear of partner divorce and violence, HIV-related stigma and discrimination, lack of psychological support, religious belief, shortage of drug supply, inadequate service access, and breach of confidentiality by HCWs were major reasons for women’s lost. Healthcare workers’ commitment to searching for lost women, partners’ encouragement to resume care, and women’s desire to live healthily were explored as reasons for resumption after LTFU. Women empowerment, partner engagement, involving community and religious leaders, awareness creation on the effect of HIV-related stigma and discrimination for the community, and service delivery as per the protocol were of vital importance to retain women on care and resume care after LTFU. Besides, HCWs should address false beliefs related to the disease during counseling sessions to retain women in care.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

WHO. HIV statistics, globally and by WHO region, 2023. WHO, Epidemiological [Internet]. 2023;1–8. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/overview

WHO. HIV/AIDS WHO Regional Office for Africa [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/hivaids%0A

UNICEF. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission [Internet]. UNICEF Data: Monitoring the situation of children and women. 2023. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/5 in 6 paediatric HIV infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa in 2022emtct/

Frontières, M. S. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Medecins Sans Frontieres; 2020. p. 45.

FMoH. Health Sector Transformation Plan HSTP II(2020/21–2024/25). Vol. 25. Addis Ababa; 2021.

Facha, W., Tadesse, T., Wolka, E. & Astatkie, A. Magnitude and risk factors of mother-to-child transmission of HIV among HIV-exposed infants after Option B+ implementation in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 21(1), 1–12 (2024).

Endalamaw, A., Demsie, A., Eshetie, S. & Habtewold, T. D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of vertical transmission route of HIV in Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 18(1), 1–11 (2018).

Kassa, G. M. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 18(1), 1–9 (2018).

Geremew, D., Tebeje, F. & Ambachew, S. Seroprevalence of HIV among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res. Notes https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-4022-1 (2018).

Getaneh, T. et al. Early diagnosis, vertical transmission of HIV and its associated factors among exposed infants after implementation of the Option B + regime in Ethiopia : A systematic review and meta-analysis. IJID Regions 4(September 2021), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.05.011 (2022).

FMoH. National comprehensive and integrated prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV guideline. Addis Ababa; 2017. p. 97.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection:Recommendations for a public health approach. WHO Press. 2013. p. 251.

FMoH. National comprehensive PMTCT/MNCH integrated training manual. Addis Ababa: FMoH; 2021. p. 368–70.

FMoH. Competency-based national comprehensive PMTCT/MNCH training participant ’s manual. Addis Ababa; 2017. p. 357.

FMoH. National comprehensive HIV prevention, care, and treatment training participant manual. FMoH. 2021. p. 158.

USAID. Tenofovir, Lamivudine and Dolutegravir (TLD) Transition [Internet]. 2019. p. 2. Available from: https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/linkages-tld-transition-information.pdf

WHO. Updated recommendations on first-line and second-line antiretroviral regimens and post-exposure prophylaxis and recommendations on early infant diagnosis of HIV: interim guidelines. Geneva (2018).

Walmsley, S. L. et al. Dolutegravir plus Abacavir-Lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 369(19), 1807–1818 (2013).

Astawesegn, F. H., Stulz, V., Conroy, E. & Mannan, H. Trends and effects of antiretroviral therapy coverage during pregnancy on mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. Evidence from panel data analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07119-6 (2022).

UNAIDS. Global HIV statistics [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf

FMoH. Implementation manual for DTG rollout and ART optimization in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa; 2019. p. 56.

Chaka, T. E. & Abebe, T. W. K. R. Option B+ prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS service intervention outcomes in selected health facilities, Adama town, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 11, 77–82 (2019).

Demissie, D., Bayissa, M., Maru, H. & Michael, T. Assessment of loss to follow-up (LTFU) and associated factors among pregnant women initiated antiretroviral under Option B+ in selected health facilities of West Zone Oromia, Ethiopia. EC Gynaecol. 8(5), 314–321 (2019).

Almado, G. A. & King, J. E. Retention in care and health outcomes of HIV-exposed infants in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cohort in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 13, 171–179 (2021).

Azanaw, M. M., Baraki, A. G. & Yenit, M. K. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among pregnant and lactating women in the Option B+ PMTCT program in Northwestern Ethiopia: A seven-year retrospective cohort study. Front. Glob. Women’s Health. 4(July), 1–12 (2023).

Tolossa, T., Kassa, G. M., Chanie, H., Abajobir, A. & Mulisa, D. Incidence and predictors of lost to follow-up among women under Option B+ PMTCT program in western Ethiopia: A retrospective follow-up study. BMC Res. Notes 13(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4882-z (2020).

Kim, M. H. et al. Why did I stop? Barriers and facilitators to uptake and adherence to ART in option B+ HIV care in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS ONE 11(2), 1–16 (2016).

Getaneh, T., Negesse, A. & Dessie, G. Experiences and reasons of attrition from option B+ among mothers under prevention of mother to child transmission program in northwest Ethiopia: Qualitative study. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 13(8), 851–859 (2021).

Mpinganjira, S., Tchereni, T., Gunda, A. & Mwapasa, V. Factors associated with loss-to-follow-up of HIV-positive mothers and their infants enrolled in HIV care clinic: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 20(1), 1–10 (2020).

Sariah, A. et al. Why did I stop? and why did I restart? Perspectives of women lost to follow-up in option B+ HIV care in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1–11 (2019).

Kassaw, M. W., Matula, S. T., Abebe, A. M., Kassie, A. M. & Abate, B. B. The perceived determinants and recommendations by mothers and healthcare professionals on the loss-to-follow-up in Option B+ program and child mortality in the Amhara region, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 20(1), 1–13 (2020).

Cataldo, F. et al. Exploring the experiences of women and health care workers in the context of PMTCT Option B plus in Malawi. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 74(5), 517–522 (2017).

Masereka, E. M. et al. Increasing retention of HIV positive pregnant and breastfeeding mothers on Option B+ by upgrading and providing full time HIV services at a lower health facility in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1–6 (2019).

FMoH. National strategic plan for triple elimination of transmission of HIV , Syphilis , and Hepatitis B virus 2021–2025. Addis Ababa; 2021.

UNAIDS. The Path That Ends AIDS. The 2023 UNAIDs Global AIDS Update. 2023.

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG Resource Document [Internet]. 2015;1–19. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030 Agenda for Sustainable Development web.pdf

UNAIDS. The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 6]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-global-hiv-aids-epidemic/

Gray, J. R., Grove, S. K. & Sutherland, S. Burns and Grove’s Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence [Internet]. 8th ed. Elsevier Inc; 2017. 70–72 p. Available from: https://lccn.loc.gov/2016030245

Wikepedia. South Ethiopia Regional State [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Ethiopia_Regional_State#cite_note-3

Sadeeh, R. The Role of Mother Support Groups. In: WHO [Internet]. 1993. p. 62–119. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/58728/WHO_NUT_MCH_93.1_(part2).pdf

Farré, L. The Role of Men in the Economic and Social Development of Women [Internet]. World Bank Blogs. 2013. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/the-role-of-men-in-the-economic-and-social-development-of-women

Mondal, D., Karmakar, S. & Banerjee, A. Women’s autonomy and utilization of maternal healthcare in India: Evidence from a recent national survey. PLoS ONE 15(12), 1-12 December. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243553 (2020).

Gugsa, S. et al. Exploring factors associated with ART adherence and retention in care under Option B+ strategy in Malawi: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 12(6), 1–18 (2017).

Kisigo, G. A. et al. “At home, no one knows”: A qualitative study of retention challenges among women living with HIV in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 15, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238232 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the staff of the South Ethiopia and Central Ethiopia Regional Health Bureaus for their technical and logistic support. Moreover, the authors sincerely thank the research assistants who translated and transcribed the interview. The authors would also like to thank the study participants who were involved in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.F. was involved in the study's conception, design, execution, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript drafting. T.T., E.W., and A.A. were involved in the project concept, guidance, and critical review of the article. All the authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agreed to publish it in scientific reports.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Wolaita Sodo University (ethical approval number WSU41/32/223). The study was carried out following relevant legislation and ethics guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before an interview, and interviewee anonymity was guaranteed.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Facha, W., Tadesse, T., Wolka, E. et al. A qualitative study on reasons for women’s loss and resumption of Option B plus care in Ethiopia. Sci Rep 14, 21440 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71252-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71252-2

- Springer Nature Limited