Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a relatively common disease, and preventing its occurrence is important for both individual health and reducing social costs. Shift work is reported to have several negative effects on health. An association has been observed between NAFLD and both sleep time and quality; however, this association remains unclear in night shift workers. We aimed to evaluate the relationship between shift work and the incidence of NAFLD. Overall, 45,149 Korean workers without NAFLD were included at baseline. NAFLD was defined as the presence of a fatty liver observed on ultrasonography without excessive alcohol use. incidence rate ratios for incident NAFLD were estimated using negative binomial regression according to age groups (20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s). In the 20s age group, shift work showed a significant incidence rate ratio (IRR) for NAFLD in all models. After adjusting for all variables, the IRR (95% confidence interval) was 1.24 (1.08–1.43) in the 20s age group. In their 20s, a significant association between shift work and incident NAFLD was consistently observed among women and workers with poor sleep quality. In this large-scale cohort study, shift work was significantly associated with the development of NAFLD among young workers in their 20s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fatty liver disease is caused by excessive fat accumulation in liver tissue. One of the most prevalent type of fatty liver is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), estimated to affect 47 incident cases per 1,000 person-years worldwide, with a global prevalence of approximately 32%1. NAFLD can cause liver damage and is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and subsequent mortality2. Therefore, preventing the occurrence of NAFLD is important for individual health and reducing social costs. In addition, NAFLD can be prevented by improving lifestyle, and thus exploring its cause from a health perspective is imperative3.

“Shift work” generally includes daily work hours outside of standard daylight hours of 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM. In South Korea, shift work is defined by law as work between 10 PM and 6 AM the following day4. According to the 6th Working Environment Survey conducted in 2020–2021, shift workers in Korea accounted for approximately 11% of wage earners5. Several studies have reported that shift and night works have negative health effects. The disease spectrum ranges from cardiovascular diseases to cancer, metabolic disorders, sleep disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, and mental health disorders6,7,8,9,10,11.

In general, NAFLD is known to be associated with components of metabolic syndrome, and studies have reported that risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, are also associated with the development of NAFLD3,12,13,14. There had been a lack of longitudinal study on the effect of shift work on the occurrence of NAFLD, but a recent study of approximately 280,000 wage earners by the UK Biobank found a significant association between night-shift work and the occurrence of NAFLD15. Compared to the group that rarely worked night shifts, the group that frequently worked at night showed hazard ratios approximately 1.2 times higher, and the risk is more pronounced in those working for > 10 years than their counterparts who worked < 10 years. A recent study in China that followed approximately 14,000 railroad workers for 4 years also showed that night shift workers had a 1.1 times higher risk of developing NAFLD, and the risk tended to increase in groups with frequent night shift work16.

In a previous investigation utilizing the same cohort data as our study, an association was observed between NAFLD and both sleep time and quality. Specifically, the incidence of NAFLD appeared to increase by approximately 1.1 times when the daily sleep time was < 7 h. However, night shift workers were excluded from the analysis during the study selection process17. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between shift work and the incidence of NAFLD, focusing on the differences in the association between age and sleep quality.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a longitudinal study that included participants of the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study who underwent a comprehensive health check-up with liver ultrasonogram. This included baseline data and follow-up at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Center in Seoul and Suwon, Republic of Korea, between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2019 (n = 333,515). It tracks and analyzes health examination results of healthy people over an extended period. The goal was to identify the health status of Koreans and create strategies to predict and prevent future health complications. More than 80% of the screened participants were employees (and their spouses) of various business corporations and local governmental organizations who registered for health screening in their workplaces.

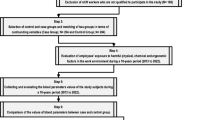

The exclusion criteria at the first visit were as follows: missing information of work schedule regarding daytime or shift work (n = 93,197) and working hours (n = 98,329); history of malignancy (n = 7613); history of liver disease or medication use for hepatitis (n = 34,257); medication for cirrhosis or finding of cirrhosis on a ultrasonogram (n = 113); heavy alcohol drink habits of 30 g/day for men or of 20 g/day for women; medication use associated with hepatic steatosis such as amiodarone, tamoxifen, methotrexate, valproate or steroid (n = 644); positive serologic markers for hepatitis B or hepatitis C (n = 10,676); fatty liver on a ultrasonogram (n = 95,072); aged < 20 or > 59 years (n = 8627); and those who worked < 35 h per week, being considered as part-time workers (n = 52,191). Overall, 88,966 people were selected and 43,817 were subsequently excluded for not completing the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire. Therefore, 45,149 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

The Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved this study (approval number: KBSMC2023-11–002) and waived the requirement for informed consent because we used only de-identified data obtained during routine health-screening examinations. All methods of the study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations including Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurements

All examinations were conducted at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Health Care Center in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea18. Medical history, medications, working hours, shift work status (daytime or shift work), shift work type (fixed, rotating, and others), alcohol consumption, smoking status, exercise frequency, and education level were collected at each clinical visit using standardized questionnaires. The question “In the past year, what time of day have you mostly worked?” measures the type of work performed. The following responses were possible: “I mostly worked during the day (between 6 AM and 6 PM.) or “I worked during other hours”. We classified participants who answered the latter as shift workers. Shift type included fixed shift work (evening or night shift), rotating shift work (regular day and night shifts, 24-h shifts, and irregular shift work), and others (split shift).

Exercise habits were evaluated using the following question: “Frequency of vigorous leisure-time physical activity per week.” Regular exercise was defined as exercising at least three times per week. A high education level was defined as college graduate or higher. After excluding heavy alcohol drink habits, alcohol consumption status was categorized as non-drinking, light drinking, or moderate drinking. Light drinking was defined as ≥ 1 g/day but < 10 g/day. Moderate drinking was defined as ≥ 10 g/day but < 20 g/day for women and ≥ 10 g/day but < 30 g/day for men. The smoking status was categorized as never smoked, former smoker, or current smoker. The PSQI is a validated, self-administered questionnaire used to generate seven-component scores calculated using 19 items that reflect subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime function19. Poor and good sleep quality was defined as a PSQI score of ≥ 6 and ≤ 5 points, respectively. On the day of the health examination, a trained nurse verified the questionnaire for blanks, and a trained doctor double-checked the questionnaire for mistakes or blanks while conducting a face-to-face interview with the examinee.

Height and weight were measured by well-trained nurses with the participants wearing lightweight hospital gowns and no shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 1 mm using a stadiometer with the participant standing barefoot. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a bioimpedance analyzer (InBody 3.0, Inbody 720, Biospace Co., Seoul, Korea). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Trained nurses measured blood pressure (BP) while participants were in a sitting position with their arms supported at heart level. Blood specimens were collected from the antecubital vein after at least 10 h of fasting. Fasting blood measurements included glucose, total cholesterol, and fasting insulin. Insulin resistance was assessed using the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) equation as follows: fasting insulin (μU/mL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/40520.

Abdominal ultrasound was performed using a Logic Q700 MR 3.5-MHz transducer (GE, Milwaukee, WI, USA) by experienced radiologists who were blinded to our study aim. Images were obtained in a standard fashion with the patients in the supine position with their right arm raised above their heads21. An ultrasonographic diagnosis of fatty liver was defined as the presence of a diffuse increase in fine echoes in the liver parenchyma compared with that in the kidney or spleen parenchyma22. The inter- and intra-observer reliabilities in the diagnosis of fatty liver were very high (kappa statistics of 0.74 and 0.94, respectively)23. NAFLD was defined as the presence of fatty liver in the absence of excessive alcohol use (≥ 20 g/day for women and ≥ 30 g/day for men) or other identifiable causes, as described in the exclusion criteria. As we have excluded participants with excessive alcohol use and other identifiable causes of fatty liver at baseline, incident cases of fatty liver were considered NAFLD. Recently, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) was proposed globally as a new term for NAFLD but considering that NAFLD has still used in clinical guidelines in Korea, the primary outcome was classified as NAFLD in the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (Chi-square test and t-test) were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the participants categorized by shift work status (daytime vs. shift worker). The primary endpoint was NAFLD development. Participants were followed up from baseline to the endpoint visit or the last available visit until December 31, 2019, whichever came first.

To evaluate the risk of NAFLD in shift workers, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incident NAFLD were estimated using negative binomial regression according to age group at 10-year intervals. We initially adjusted for age and sex in Model 1. Model 2 was further adjusted for smoking status, regular exercise, educational level, systolic BP, fasting blood glucose level, total cholesterol level, BMI, and HOMA-IR. To explore the mechanism underlying the observed associations between shift work and the risk of incident NAFLD, Model 3 was further adjusted for the PSQI. To explore whether the association between shift work and NAFLD differed, subgroup analyses were performed based on sleep quality (good vs. poor) and sex (men vs. women). Interactions between the age groups and clinically relevant subgroups were tested using likelihood ratio tests, which compared models with and without interaction terms.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All reported p-values are two-tailed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB No: KBSMC2023-11-002), which waived the requirement for informed consent because only de-identified data obtained as part of routine health screening examinations were used.

Results

We analyzed the baseline characteristics of 45,149 participants, comprising 39,528 daytime workers (87.6%) and 5,621 shift workers (12.4%). The average age (standard deviation) of daytime workers was 34.5 (6.1) years, while that of the shift workers was 30.6 (6.1) years. Among daytime workers, those in their 30s accounted for the largest proportion (58.9%), with a significant difference from the other age groups. In contrast, shift workers were similarly distributed in their 20s and 30s at 50.3% and 41.1%, respectively, comprising the majority of shift workers. The incidence of NAFLD in both daytime and shift work workers was similar at approximately 19%. The proportion of male workers was higher in those with daytime than in those with shift work (57.3% vs. 46.4%, respectively). Shift workers exhibited a slightly higher rate of nondrinking or moderate alcohol drinking habit, whereas daytime workers had a slightly higher rate of light drinking. In both the daytime and shift worker groups, the proportion of current smokers was lower than that of non-smokers or former smokers. Conversely, the proportion of current smokers in the daytime worker group was higher than that in the shift worker group. Although the differences in systolic blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, total cholesterol, BMI, and HOMA-IR between the two groups were statistically significant, the values were relatively similar. The average PSQI score for sleep quality was 5.6 and 4.9 points for shift and daytime workers, respectively, indicating that shift workers had poorer sleep quality. The proportion of individuals with good sleep quality of 5 points or less also showed a difference between the daytime and shift workers (63.9% vs. 53.6%, respectively) (Table 1).

As the age group increased, the incidence rate of NAFLD tended to increase, but the incidence rate was highest in those in their 40s and lowest in those in their 20s. The IRR of NAFLD according to age group at 10-year intervals was obtained. In the 20s age group, shift work showed a significant IRR value for NAFLD in all models. After adjusting for all variables, the IRR (95% CI) was 1.24 (1.08–1.43) in the 20s age group. Conversely, in the 40s and 50s age group, all models showed non-significant IRR values. The results were similar even when the age groups in their 40s and 50s were combined to increase statistical power and obtain more accurate IRR. In the 30s age group, only Model 2 showed significant values (Table 2).

The effects of daytime and shift work on the occurrence of NAFLD varied across age group, delineating subgroups based on their sleep quality, as assessed by the PSQI. In the 30s and 40–50s age groups, daytime or shift work schedules did not show a significant risk, regardless of sleep quality. However, in the 20s age group, shift work significantly increased the risk compared with daytime work only in the group with poor sleep quality, with an IRR (95% CI) of 1.37 (1.11–1.70). Upon stratification by sex, the IRR of NAFLD for shift work compared to daytime work according to age group was significant only for women in their 20s, with an IRR (95% CI) of 1.39 (1.05–1.84). No significant interactions was observed between sleep quality and age, sex, or age group (Table 3).

Discussion

This large prospective cohort included measures of working conditions such as shift work status, subjective sleep quality, and NAFLD status. We studied the impact of poor working conditions on individual health and disease occurrence and selected only workers aged 20–59 years. The average age of daytime workers in this study was 34 years, and that of the shift workers was 30 years. In the initial participant selection, those with fatty liver on ultrasonography were excluded; therefore, 82% of the total study participants were young workers in their 20s and 30s. Approximately 90% of shift workers were in their 20s and 30s. We found that shift work was significantly associated with the development of NAFLD in young workers in their 20s. This was consistent even after adjusting for covariates, such as BP, fasting glucose, cholesterol, BMI, insulin resistance, and sleep quality. Notably, in the stratified analysis, the association was retained only in the group with poor sleep quality and women, and no interaction was observed in each stratified analysis.

To the best of our knowledge, the mechanisms underlying the increased risk of developing NAFLD in young shift workers remain unknown. A study indicated that older adults are more susceptible to various liver diseases, such as NAFLD24. Moreover, previous studies revealed that older shift workers have a higher risk of developing NAFLD, which was explained by their lower resistance to oxidative stress induced by circadian changes16,25. However, as aging progresses, the exposure to risk factors for NAFLD, such as lack of exercise, obesity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, increases24,26. After adjusting for these major factors, it was assumed that the impact of shift work on NAFLD in older workers was minimal. Additionally, the healthy worker effect, which suggests that healthier people are more likely to tolerate shift work as they age, should also be considered.

Shift workers have shorter sleep durations and poorer sleep quality27. Previous studies on sleep restriction in young men and women have reported that plasma leptin levels decrease, and ghrelin levels increase28. This increases both appetite and fat intake, subsequently causing obesity and diabetes, leading to an increased risk of developing NAFLD29,30,31. One study found that younger people were more vulnerable to sleep restriction than older people32. Previous studies on sleep duration and the development of NAFLD have reported conflicting results. Of the two cohort studies using health examination data from the general Japanese population from the 2000s to the 2010s, one found that short sleep duration increased the risk of NAFLD33, while the other found that it decreased the risk in men34. Meta-analyses have also shown that short sleep duration increases the risk of developing NAFLD35,36, whereas another study found that long or short sleep duration did not increase the risk37. Therefore, based on previous studies, no consistent conclusions can be drawn regarding sleep duration and risk of developing NAFLD. Meanwhile, evidence on the impact of sleep quality, rather than sleep time, on the occurrence of NAFLD is lacking. A cross-sectional study from the same data source as our study was conducted approximately 10 years ago and reported that not only sleep time but also sleep quality increased the risk of developing NAFLD38. After adjusting for variables similar to those in our study, an odds ratio of approximately 1.1 and 1.4 was presented for men and women, respectively, indicating that the risk was greater for women than for men. Recently, a cohort study using the same data source as our study, which analyzed both sleep duration and sleep quality, revealed that poor sleep quality slightly increases the incidence of NAFLD17. These two studies excluded night shift workers from the study participant selection process, whereas our study focused on examining shift work and the risk of developing NAFLD.

We found that female shift workers in their 20s had an increased risk of developing NAFLD. A previous cohort study of healthy young adults showed that during sleep deprivation, serum leptin levels decreased significantly more in women than in men28. Another study found that after acute sleep restriction, both men and women had higher cortisol levels in the afternoon; however, morning cortisol levels were lower in women than in men39. These differences may indicate that the hormonal effects of sleep deprivation differ according to sex. However, because the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, further research is needed to understand the biological mechanisms of these hormones. Additionally, a large-scale Korean study reported that shift work-related negative health behaviors that increase the risk of NAFLD, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, differ depending on sex40. In that study, only female shift workers were more likely to be current smokers, and both younger women and all age group of men had a high prevalence of alcohol consumption. This is because the prevalence of female smokers in South Korea is markedly low and younger women are more vulnerable to alcohol consumption owing to their prolonged exposed to shift work-related stress due to long working hours for shift work.

Our study has few limitations. First, selection bias among the final population may need to be considered because more individuals with incomplete PSQI questionnaires were excluded than expected. However, as there were no significant differences between the two groups when comparing baseline characteristics, this effect appears to be minimal. Second, because the PSQI is a self-reported questionnaire, the results are expected to be more robust if objective test results, such as electroencephalography or polysomnography, are included to Supplement the survey results. Third, as the amount of alcohol intake was measured using a self-reported questionnaire, the amount could be underreported. However, there was no objective indicator to measure alcohol intake in health check-up. In addition, there was no benefit to the subject if they underreported the amount of alcohol intake, or there was no disadvantage to alcohol excessive use. And measurement errors in the amount of alcohol intake were not expected to show a significant trend according to age, therefore it is unlikely to have a significant impact on the results of this study. Fourth, because the working hours survey did not separately assess working hours in shift work, limitations exist in quantifying the exact impact of shift work. This issue needs to be addressed in future studies. Finally, the failure to investigate dietary patterns as confounding variables is a limitation in understanding the underlying mechanism. Nevertheless, because our study was a large-scale longitudinal study, and the variables were investigated in a refined manner by experienced experts, the results have the advantage of being more reliable than those of previous studies. Additionally, because the study population consisted of relatively healthy and young participants, it has strengths over previous studies in terms of minimizing the impact of underlying diseases and evaluating the independent effects of shift work.

In conclusion, shift work was significantly associated with the development of NAFLD among young workers in their 20s. This association was significantly more pronounced among young female workers and young workers with poor sleep quality across all sexes.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available because we do not have permission from the Institutional Review Board to distribute the data. However, data are available from the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study upon reasonable request to the corresponding author of this manuscript.

References

Teng, M. L. et al. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29, S32–S42 (2023).

Cotter, T. G. & Rinella, M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 2020: The state of the disease. Gastroenterology 158, 1851–1864 (2020).

Sarwar, R., Pierce, N. & Koppe, S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: current perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 11, 533–542 (2018).

Labor Standards Act: Article 56 (Extended, Night or Holiday Work) [cited 2024 13 April]. https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?lang=ENG&hseq=59932.

Korean Working Conditions Survey 6th[cited 2024 13 April]. https://oshri.kosha.or.kr/oshri/researchField/downWorkingEnvironmentSurvey.do.

Gao, Y. et al. Association between shift work and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Chronobiol. Int. 37, 29–46 (2020).

Manouchehri, E. et al. Night-shift work duration and breast cancer risk: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health 21, 89 (2021).

Nam, M. W., Lee, Y., Mun, E. & Lee, W. The association between shift work and the incidence of reflux esophagitis in Korea: A cohort study. Sci. Rep. 13, 2536 (2023).

Ohayon, M. M., Lemoine, P., Arnaud-Briant, V. & Dreyfus, M. Prevalence and consequences of sleep disorders in a shift worker population. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, 577–583 (2002).

Torquati, L., Mielke, G. I., Brown, W. J., Burton, N. W. & Kolbe-Alexander, T. L. Shift work and poor mental health: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Am. J. Public Health 109, e13–e20 (2019).

Torquati, L., Mielke, G. I., Brown, W. J. & Kolbe-Alexander, T. Shift work and the risk of cardiovascular disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis including dose-response relationship. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 44, 229–238 (2018).

Oikonomou, D. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hypertension: Coprevalent or correlated?. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 30, 979–985 (2018).

Tilg, H., Moschen, A. R. & Roden, M. NAFLD and diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 32–42 (2017).

Chatrath, H., Vuppalanchi, R. & Chalasani, N. Dyslipidemia in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 32, 22–29 (2012).

Huang, H., Liu, Z., Xie, J. & Xu, C. Association between night shift work and NAFLD: A prospective analysis of 281,280 UK Biobank participants. BMC Public Health 23, 1282 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Shift work and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease incidence among Chinese rail workers: A 4-year longitudinal cohort study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 96, 179–190 (2023).

Um, Y. J. et al. Sleep duration, sleep quality, and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A cohort study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 12, e00417 (2021).

Chang, Y. et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111, 1133–1140 (2016).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. 3rd., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Chang, Y., Ryu, S., Sung, E. & Jang, Y. Higher concentrations of alanine aminotransferase within the reference interval predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Chem. 53, 686–692 (2007).

Mathiesen, U. L. et al. Increased liver echogenicity at ultrasound examination reflects degree of steatosis but not of fibrosis in asymptomatic patients with mild/moderate abnormalities of liver transaminases. Dig. Liver Dis. 34, 516–522 (2002).

Ryu, S. et al. Age at menarche and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 62, 1164–1170 (2015).

Kim, I. H., Kisseleva, T. & Brenner, D. A. Aging and liver disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 31, 184–191 (2015).

Martin, C. et al. Effect of age and photoperiodic conditions on metabolism and oxidative stress related markers at different circadian stages in rat liver and kidney. Life Sci. 73, 327–335 (2003).

Cunningham, C., O’Sullivan, R., Caserotti, P. & Tully, M. A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30, 816–827 (2020).

Yong, L. C., Li, J. & Calvert, G. M. Sleep-related problems in the US working population: Prevalence and association with shiftwork status. Occup. Environ. Med. 74, 93–104 (2017).

van Egmond, L. T. et al. Effects of acute sleep loss on leptin, ghrelin, and adiponectin in adults with healthy weight and obesity: A laboratory study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 31, 635–641 (2023).

Al Khatib, H. K., Harding, S. V., Darzi, J. & Pot, G. K. The effects of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 71, 614–624 (2017).

Lian, C. Y., Zhai, Z. Z., Li, Z. F. & Wang, L. High fat diet-triggered non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A review of proposed mechanisms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 330, 109199 (2020).

Buxton, O. M. et al. Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 129–143 (2012).

Zitting, K. M. et al. Young adults are more vulnerable to chronic sleep deficiency and recurrent circadian disruption than older adults. Sci. Rep. 8, 11052 (2018).

Okamura, T. et al. Short sleep duration is a risk of incident nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A population-based longitudinal study. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 28, 73–81 (2019).

Miyake, T. et al. Short sleep duration reduces the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease onset in men: A community-based longitudinal cohort study. J. Gastroenterol. 50, 583–589 (2015).

Wijarnpreecha, K., Thongprayoon, C., Panjawatanan, P. & Ungprasert, P. Short sleep duration and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 31, 1802–1807 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Short sleep duration and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/metabolic associated fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 27, 1985–1996 (2023).

Shen, N., Wang, P. & Yan, W. Sleep duration and the risk of fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 31956 (2016).

Kim, C. W. et al. Sleep duration and quality in relation to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged workers and their spouses. J. Hepatol. 59, 351–357 (2013).

Omisade, A., Buxton, O. M. & Rusak, B. Impact of acute sleep restriction on cortisol and leptin levels in young women. Physiol. Behav. 99, 651–656 (2010).

Bae, M. J. et al. The association between shift work and health behavior: Findings from the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey. Korean J. Fam. Med. 38, 86–92 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted using data provided by the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study. The authors thank all study participants and personnel for their dedication and continuing support.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.L.; Methodology: W.L.; Formal analysis and investigation: Y.L. and W.L.; Writing—original draft preparation: Y.L.; Writing—review and editing: Y.L. and W.L. Guarantor of the article: W.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y., Lee, W. Shift work and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in young, healthy workers. Sci Rep 14, 19367 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70538-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70538-9

- Springer Nature Limited