Abstract

Mutual trust is considered one of the critical aspects of building a successful doctor-patient relationship. Albeit patient trust in physicians has been widely explored by researchers, physician trust in patients remains neglected, which is reflected by the lack of existing tools to assess this construct. Therefore, we aimed to validate and adapt Thom’s Physician’s Trust in the Patient Scale (PTPS) in Polish. We conducted a survey-based study among 307 medical doctors. To determine the factor structure of the scale, both exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed. The two-factor solution was established for the scale in accordance with the original version. To determine the internal reliability and consistency of the scale, we measured Cronbach’s alpha, corrected-item total correlation, and discrimination indices—all of them obtained very good or excellent values. Estimates of convergent and discriminant validity reached all suggested thresholds. The scale also performed well in theoretical validity. Together, these findings suggest that the psychometric properties of the Polish adaptation and validation of PTPS are satisfactory and that the tool can find practical and scientific applications. We believe that the scale can substantially add to our understanding of building trust-based relationships and rapport between patients and physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

In the present day, medicine cannot be considered solely an instrumental field of science. It needs to incorporate other disciplines, like social sciences, which emphasize the human context, to comprehend the needs of patients and physicians better. One such aspect of medicine is trust in the physician–patient relationship.

Interpersonal trust plays a crucial, sometimes underestimated, role in the physician–patient relationship and its short- and long-term effects1,2,3,4,5. It can be defined as an expectation of another person to act advantageously or at least harmlessly6,7. Taking into account the physician–patient relationship, mutual trust is essential to provide/obtain the proper diagnostic process, improve or maintain the condition and health of the patient, and maintain intact continuity of care8,9,10. Trust also includes a component of risk. The trustor is willing to be vulnerable to the trustee's actions based on the assumption of their good intentions5,11.

In the context of a physician–patient relationship, many examples exist of taking this risk and deciding to trust the other party on both sides of the interaction. Patients adopt a trusting attitude toward physicians by recognizing their competence, experience, and knowledge, sharing personal information, and being honest about their doubts or lack of understanding of the proposed medical care1,12,13. Patient trust in the physician impacts better engagement in a treatment process, a more meaningful relationship with the healthcare provider, or greater satisfaction with the medical service10,14,15,16. Physicians base trust in patients on honesty in disclosing symptoms, adhering to treatment, keeping medical appointments, or respecting their boundaries17,18,19. Physician trust in patients is reflected in involving them in the treatment process and shared decision-making more willingly7,15,20,21.

Patients' perceptions of physicians’ trust in them are associated with continuity of care and the feeling of being treated as a partner in this relationship10,21,22,23. Trusted patients feel more respected, taken seriously, considered the experts of their bodies, and more often reciprocate the trust5,10,21,22,24. Moreover, experiencing trust from the care provider facilitates patients’ sense of competence regarding managing their medical problems21,23. This can result in better engagement in the treatment process, feeling responsible for their own health problems, and much more sincere and open communication with physicians10,21,22,23. That, in turn, leads to better diagnostic outcomes along with appropriate therapy adjustments and building concordance instead of adherence21,22,23. “When physicians stop simply seeking patients’ adherence to their proposed care plans and instead work with patients toward a co-created strategy that reflects each patient’s beliefs, values, preferences, and abilities, the groundwork for mutual trust is effectively laid and healing can begin.”22 Furthermore, the research has shown that higher levels of physician’s trust in patients are related to higher levels of job satisfaction, which constitutes a great counterbalance to burnout5,22,23. Trust-based relationships with patients can be characterized as more qualitative, intrinsically valuable, and meaningful for physicians5,25,26. Trusting physicians tend to have greater self-trust and self-confidence, respecting their technical and non-technical competencies26.

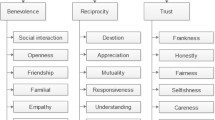

Albeit, mutual trust appears to be a critical aspect of the physician–patient relationship and rapport, it is rarely investigated in research4,5,8,10,19,21. Studies on the scope of patient trust in physicians outnumbered those considering physician trust in patients14,21,24,26,27,28,29. This situation is reflected in the limited number of tools developed to measure physician trust in the patient7,21,30. One such tool is the Physician Trust in the Patient Scale (PTPS)7, which consists of 12 items assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = 'not at all confident' to 5 = ‘completely confident’) and comprises two factors: Patient Role and Respect for Boundaries (Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). Patient Role (Factor 1) covers the area of physicians' expectations regarding patients' behavior, providing complete, accurate information, treatment engagement, adherence, and appointment continuity. Respect for Boundaries (Factor 2) considers respecting physicians’ boundaries or time and participating in medical appointments without making unreasonable demands or manipulating their course for personal gain. The PTPS presents very good psychometric properties with a high level of internal reliability, consistency, convergent, and discriminant validity7.

This study aimed to carry out a Polish adaptation of the Physician Trust in the Patient Scale (PTPS), as well as to determine its internal structure and psychometric properties: reliability and convergent, discriminant, theoretical, and criterion validity. The convergent and discriminant validity was estimated by the following measurements: Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Maximum Shared Variance (MSV), and Average Shared Variance (ASV). The theoretical validity was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients (individual items and the total score of the questionnaire). Since, to the best of our knowledge, there is no other tool to assess physicians’ trust in patients, we have not been able to compare this construct directly to other scales. Hence, to assess the criterion validity, we had to choose similar constructs connected to trust: general trust, integrity, disposition to trust, sense of competence, and trusting beliefs. Based on research and links between institutional trust31, trust relationships in the work environment32 as well as trust in the healthcare system33 and professional burnout, we decided to include also burnout with its both dimensions: exhaustion and distance, as well as connected with them—job satisfaction.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study included 307 medical doctors (168 women, 138 men, and one person who did not identify with any of the above genders) with various medical specialties (all 51 represented specialties are shown in Table S3 in Supplementary Materials) from 26 different cities in Poland. The sample size was based on recommendations for best practices in EFA, assuming the item-to-sample ratio of 20:1 as the most accurate34. Therefore, expecting an average of 20% data loss, we estimated the sample size as 300. The inclusion criteria for the participants were an active medical license and ongoing practice with patients.

The physicians were between 25 and 72 years old (M = 45, SD = 12.7); the length of their professional experience ranged between 1 and 49 years (M = 19.4, SD = 12.8). The vast majority of respondents (84.49%) declared to be in a stable relationship; 68.42% declared to have children. About two-thirds of the participants (62.95%) described their financial status as above average, 34.75% as average, and only 2.3% as below average. Doctors differed in terms of healthcare sector and principal place of employment—282 of them work in the public sector and 60 in private; 241 doctors indicated multispecialty hospitals as their leading workplace, 19—single-profile hospitals, 27—specialist outpatient clinics, 18—primary care and 33—private practice (choosing more than one place of employment was allowed in the survey).

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology in Wroclaw, SWPS University, approved the study protocol (No. 06/P/03/2022). Research has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the methods implemented in the study were aligned with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Invitations with a link to the online survey (prepared in Qualtrics) were sent via email to hospitals, outpatient clinics, and medical universities. After informed consent, participants completed the online survey, active from 13th April to 9th August 2022 (the entry took M = 30.32 min, Me = 14.47 min). Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. The survey was entered by 338 people, and responded by 307 of them; 254 participants answered all 99 questions. The character of data loss was estimated as random; therefore, multiple imputation of missing data was implemented to carry out some measurements (regression method of FIML).

Translation procedure

The adaptation procedure was carried out using a translation and back-translation method. In the first phase, two experts in English and psychology translated Thom’s Physician Trust in Patient Scale (PTPS) into Polish. Then, two Polish psychology experts examined the convergence of both versions and prepared the preliminary version of the scale. In the next step, the scale was back-translated by a native speaker (a US citizen and medical doctor) and subsequently compared with the original version. Upon achieving satisfactory translation convergence, two psychology experts prepared the final Polish version of the tool (see Table S4 in Supplementary Materials).

Measures

In the validation procedures of the Polish adaptation of PTPS, the following tools were implemented: The Disposition to Trust & Trusting Beliefs Measure35; General Trust Scale36; Oldenburg Burnout Inventory37; Self-efficacy and Job Satisfaction subscales from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire COPSOQ II38; and Ten-Item Personality Inventory39. Table S2 in Supplementary Materials provides all the necessary data about the constructs and tools.

Statistical analysis

Validation procedures

The psychometric properties of the Polish version of the PTPS included: determining the factor structure of the questionnaire, confirmed by Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), estimating the internal reliability and consistency of the inventory (Cronbach’s alpha, corrected-item total correlation), analyzing internal structure (factor loadings, Pearson’s correlation coefficients) and the discriminatory power of the items (discrimination indices), theoretical validity, convergent and discriminant validity, and criterion validity. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS and AMOS (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, United States) version 28.

Results

Eigenvalues and factor structure

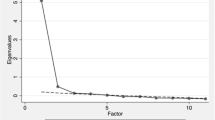

To determine the internal structure of the scale, we performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the Principal Axis Factoring (PAF)—Extraction Method. We used the scree plot criterion to establish the number of factors and subsequently obtained two-factor solution (Fig. 1). The eigenvalues for the extracted factors 1 and 2 were 5.84 and 1.5, respectively.

Together, both factors explained the 53.72% variance of the results. After performing the Promax Rotation Method with Kaiser Normalization (Rotation converged in 3 iterations), the first factor describes the role of the patient in the treatment process (Factor 1 = Patient Role) and includes items 3, 6, 2, 1, 5, 7, 4, and 12 (order by the strength of loadings; all factor loadings are high, Table 1). The second factor determines the patient’s respect for the physician’s boundaries (Factor 2 = Respect for Boundaries) and consists of items: 10, 9, 11, and 8. Item 12 did not obtain the desired factor loading (> 0.5). Albeit the weak loading of this item, we decided to leave it in the Polish adaptation of the PTPS (to keep it intact with the original one). Table 1 presents all factor loadings. The structure accurately reflects the original version of the tool.

Structural proof

We then verified the measurement model with the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). To prepare the dataset for the main analyses, we assessed the character of missing data as random. We conducted multiple imputation of the missing data using the regression method of FIML (full information maximum likelihood) in AMOS (version 28). Next, we estimated the quality of the tested model by the following indexes: CMIN/DF (Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom); CFI (the comparative fit index); GFI (goodness of fit index); AGFI (adjusted goodness of fit index); RMR (root mean square residual); and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation). Table 2 shows all desired thresholds40.

The two-factor solution derived from EFA was proved adequate by CFA. The model fits very well, as presented in Table 2. Out of 12 items, 9 achieved the desired values of factor loadings (> 0.70). The other three items (4, 7, and 12) obtained factor loadings slightly below 0.7 (Fig. 2).

Internal reliability and consistency

The internal reliability of the scale was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha (α). The Cronbach’s alpha reached the following values, considerably for Factor 1—Patient Role (8 items) α = 0.89 and Factor 2—Respect for Boundaries (4 items) α = 0.84.

We carried out the second measurement by applying the corrected-item total correlation method to establish the internal consistency of the validating scale. Table 1 shows that all the correlations range between 0.69 and 0.55.

In addition, we calculated the discriminatory power of the tested items using the discrimination index based on a point-four-field correlation coefficient. In the literature, the suggested thresholds for discrimination indexes are specified as good: < 0.30; very good: < 0.35; excellent: < 0.4041,42,43. The derived discrimination indices of individual items range from 0.31 to 0.41 (Table 1).

Theoretical validity

Pearson’s correlation coefficients helped us determine the theoretical validity of the scale by the relationships between the results obtained on individual items and the total score of the questionnaire44. All items achieved values greater than the estimated critical (0.206 for df = 284) at the high level of significance (p < 0.01). Most importantly, the correlations between them and the scale total proved very strong (ranging from 0.636 to 0.745; see Table 3).

The convergent and discriminant validity

To assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the scale's two distinguished factors, we used the following four parameters: CR (Composite Reliability), AVE (Average Variance Extracted), MSV (Maximum Shared Variance), and ASV (Average Shared Variance). All measures reached the suggested thresholds (see Table 4)40. The convergent validity for Factor 1 is acceptable, and for Factor 2, it is good.

Criterion validity

To assess the criterion validity, we chose the following constructs connected to trust in the patient: general trust, integrity, sense of competence, professional burnout, and job satisfaction. The discriminant validity of the Polish adaptation of PTPS was tested using self-efficacy and personality traits. Descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table 5.

The results of Pearson's correlation between the given constructs, the overall score, and both subscales of PTPS are shown in Table 6. Most of the constructs used to assess the criterion validity (both tested dimensions of burnout: exhaustion and distance, job satisfaction, integrity, and disposition to trust) correlated stronger with the overall score than with separate factors. However, the sense of competence and trusting beliefs (comprised of the sense of benevolence, integrity, and competence in the role of the medical doctor) achieved a higher correlation with Factor 1 (Patient Role) compared to Factor 2 (Respect for Boundaries) or the overall score. Most of the correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.01), but none of them exceeded the value of 0.3. All variables related to trust (the level of general trust, integrity, disposition to trust, and trusting beliefs, including the sense of competence) along with job satisfaction noted positive correlations with the overall score and both factors of PTPS. Burnout with its two tested dimensions (exhaustion and distance) contrarily showed a negative correlation with PTPS, Patient Role, and Respect for Boundaries.

Self-efficacy and personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness) as discriminant criteria for PTPS did not correlate with either both factors or the overall score.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to adapt and validate the Polish version of the Physician’s Trust in the Patient Scale (PTPS). After performing a battery of testing methods, we determined the tool's internal structure and psychometric properties. The measures obtained lead us to conclude that the adapted and validated Polish version of PTPS has very good psychometric properties. It is reflected by achieving desired thresholds of all important and considered dimensions: internal reliability and consistency of the tool, theoretical validity, convergent and discriminant validity, as well as criterion validity. In most cases, the derived values were highly above the suggested minimum.

The distinguished, in EFA, two-factor solution corresponded theoretically with the assumptions of the original tool7. Albeit three items (4, 7, and 12) did not reach the recommended factor loadings (0.7) in CFA, we decided to keep them in the scale to maintain concordance with the original version of the tool7. All three proved to be valid in other measurements, such as Cronbach’s alpha, discrimination index, corrected-item total correlation, or Pearson’s correlation coefficients with the total score of the questionnaire. Furthermore, the content of these items is essential in the context of the researched construct. Questions regarding a patient’s adequate understanding of the diagnosis and treatment plan or adherence to recommended treatment provide crucial information to physicians, particularly in the context of mutual trust4,21,22,45. In like manner, the salience of trust can be emphasized with regard to the continuity of care (item 12)10,21,22,23,46.

Item 12 had the weakest factor loadings in both EFA and CFA (it was the only item that did not reach the cutoff criteria in EFA). We deliberated whether to keep it in the scale or not, but as mentioned above, it brings some very important information regarding trust in patient—the continuity of care. Some other arguments in favor exist, such as correlating with other items within its factor or the results of reliability of the scale (Cronbach’s alpha is higher with item 12, discrimination index). Considering all the facts, we suggest leaving it in the scale as a buffer item. Notwithstanding the foregoing, we also prepared and shared the fit indices and the alternative model for the 11-item version of the PTPS (see Table S5 and Fig. S1 in Supplementary Materials).

Considering the internal reliability and consistency of the scale, we implemented three different methods: Cronbach’s alpha, corrected-item total correlation, and discrimination indices. The recommended maximum alpha value was 0.90, hence the obtained values (respectively total scale: α = 0.90, Factor 1: α = 0.89, and Factor 2: α = 0.84) indicate high internal reliability, simultaneously allowing us to conclude the lack of items’ redundancy. The last feature is particularly significant for exploring the physician–patient relationship; the longer the tool, the more difficult it is to gather the data (lack of time).

Corrected-item total correlation is an important tool in assessing the internal validity of multi-item scales, helping to identify questions that are strongly related to the overall score and contributing to measure the same construct47. Higher values (> 0.5) of the adjusted correlation between the item and the total score indicate greater relevance of the question in the context of the overall construct measured by the scale. All the results of our calculations reached this threshold with the lowest value = 0.55, with most of them above 0.60, indicating the tool's high internal consistency.

The discrimination index is a method of assessing item quality in multi-item scales. It indicates to what extent a given item differentiates among people with different degrees of the studied construct. We based our measurement on a comparative analysis of extreme groups, composed of 27% of the top and bottom scorers48. High values of the discriminant index (ranging from good to excellent) obtained for all PTPS items imply good quality and discriminant validity of the scale as a measurement tool.

The Polish version of PTPS also performed well in the context of theoretical validity. After calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients for all items and the scale total, we achieved values much higher than the estimated critical. Therefore, it can be concluded that all scale items are valid and in accordance with the theoretical assumptions of the measured construct—the physician’s trust in the patient.

Estimating the convergent and discriminant validity of the two factors of the scale, we assessed the Composite Reliability, the Average Variance Extracted, the Maximum Shared Variance, and the Average Shared Variance. The values obtained indicate that the Composite Reliability in both cases exceeds expectations, being significantly higher than the desired thresholds. We found no discriminant validity issues in both scale factors. The poorest of all results concerns the AVE for Factor 1. Unfortunately, we were unable to compare this result with the original English version of the tool, as in the process of deriving the original version, the authors did not use the CR, AVE, MSV, and ASV parameters to estimate the convergent and discriminant validity7. Therefore, we cannot conclude if this issue only regards the Polish adaptation or the tool in general.

In the last part of the validation process, we estimated the criterion validity, which occurred as the most challenging in interpreting its results. The obtained correlation loads proved consistent with expectations. The constructs related to trust showed a positive correlation with PTPS: higher levels of general trust, integrity, sense of competence, disposition to trust, and trusting beliefs are related to higher trust in the patient. Contrariwise, the dimensions of burnout and PTPS correlated negatively, which could indicate the unfavorable role of physicians’ burnout in trusting a patient. On the contrary, higher levels of job satisfaction seem to be associated with greater trust in the patient.

We derived relatively weak correlations ranging between 0.12 and 0.30 (p < 0.01). This situation was expected since we analyzed similar yet not identical constructs. Our explanation of these values focuses on the fact that the comparing constructs measured, for instance, trust in general or propensity to trust, which is of great importance in assessing interpersonal trust but can appear irrelevant in the case of one particular physician–patient interaction. Consequently, we addressed that in the limitations of the study.

Limitations

We can point out three main limitations of this study. There was no other existing adaptation of this tool in any other language and cultural versions, which made the comparisons of both—the adaptation and validation procedure along with the obtained measures—impossible to perform. Thence, we attempted to evidence the psychometric properties using various estimates that might appear overlapping, but conclusively, in the situation of no comparison material, served us with their methodological diversity to prove the validities of the scale. Second, the lack of other tools to assess the construct of physician trust in the patient posed many challenges in establishing the criterion validity of the scale. We addressed this by applying tools measuring similar constructs connected to trust35,36 or constructs based on a proven link with trust in different studies31,32,33. The last limitation concerns measuring only one physician–patient interaction for each tested respondent. In this regard, we recommend conducting further studies implementing the scale in relation to many patients of one physician.

Conclusions and indications

We believe that the Polish version of the Physician’s Trust in the Patient Scale can complement the existing tools in assessments of the reverse construct, the patient’s trust in the physician, and consequently contribute to a better understanding of the role of mutual trust in the physician–patient relationship. PTPS, with its good psychometric properties, can be successfully implemented in research on factors related to building trust-based relationships between physicians and their patients. We are also convinced that this tool has beneficial potential for practitioners, as it helps them realize their level of trust for a given patient and, hence, choose the adequate approach and build more qualitative relationships. Physician trust benefits the whole healthcare system, as it is associated with better treatment outcomes, improved continuity of care, and physicians with much lower burnout symptoms. Therefore, trusting patients should be one of the desired approaches that is pursued.

The participation of such a relatively large number of physicians in our validation study may reflect the real need for further investigation of the physician–patient relationship and its predictors, connected variables, and effects. Therefore, it indicates the direction for future studies—focused on the neglected area of the physician side of this relationship. One approach worth exploring could be an analysis of these interactions as dyads or even triads that include a family member or other medical professional.

Data availability

Fully anonymized data from the study is available in Mendeley Data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/x2rxtpzg4v/1.

References

Chandra, S., Mohammadnezhad, M. & Ward, P. Trust and communication in a doctor- patient relationship: A literature review. J. Healthc. Commun. 03, 1–6 (2018).

Birkhäuer, J. et al. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12, 1–13 (2017).

Dang, B. N., Westbrook, R. A., Njue, S. M. & Giordano, T. P. Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor-patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 17, 1–10 (2017).

Douglass, T. & Calnan, M. Trust matters for doctors? Towards an agenda for research. Soc. Theory and Health. 14, 393–413 (2016).

Berger, R., Bulmash, B., Drori, N., Ben-Assuli, O. & Herstein, R. The patient-physician relationship: an account of the physician’s perspective. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 9, 1–16 (2020).

Moskowitz, D. et al. Is primary care providers’ trust in socially marginalized patients affected by race?. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 846–851 (2011).

Thom, D. H. et al. Physician trust in the patient: Development and validation of a new measure. The Ann. Fam. Med. 9, 148–154 (2011).

Petrocchi, S. et al. Interpersonal trust in doctor-patient relation: Evidence from dyadic analysis and association with quality of dyadic communication. Soc. Sci. Med. 235, 112391 (2019).

Rotaru, T. Ș & Oprea, L. A patient’s trust in their doctor on the framework of Miller’s four senses of autonomy. Studia Ubb Bioethica. 60, 41–51 (2015).

Murphy, M. & Salisbury, C. Relational continuity and patients’ perception of GP trust and respect: a qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 70, E676–E683 (2020).

Van Den Assem, B. & Dulewicz, V. Doctors’ trustworthiness, practice orientation, performance and patient satisfaction. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 28, 82–95 (2015).

Skirbekk, H., Middelthon, A. L., Hjortdahl, P. & Finset, A. Mandates of trust in the doctor-patient relationship. Qual. Health Res. 21, 1182–1190 (2011).

Dugan, E., Trachtenberg, F. & Hall, M. A. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv. Res. 5, 1–7 (2005).

Blödt, S., Müller-Nordhorn, J., Seifert, G. & Holmberg, C. Trust, medical expertise and humaneness: A qualitative study on people with cancer’ satisfaction with medical care. Health Expect. 24, 317–326 (2021).

Georgopoulou, S., Nel, L., Sangle, S. R. & D’Cruz, D. P. Physician–patient interaction and medication adherence in lupus nephritis. Lupus 29, 1168–1178 (2020).

Eveleigh, R. M. et al. An overview of 19 instruments assessing the doctor-patient relationship: Different models or concepts are used. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65, 10–15 (2012).

Sousa-Duarte, F., Brown, P. & Mendes, A. Healthcare professionals’ trust in patients: A review of the empirical and theoretical literatures. Sociol. Compass. 14, 1–15 (2020).

Rotaru, T.-S., Drug, V. & Oprea, L. How Doctor-patient mutual trust is built in the context of irritable bowel syndrome: A qualitative study. Rev. De Cercet. Si Interv. Sociala. 55, 185–203 (2016).

Wilk, A. S. & Platt, J. E. Measuring physicians’ trust: A scoping review with implications for public policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 165, 75–81 (2016).

Montgomery, T., Berns, J. S. & Braddock, C. H. III. Transparency as a trust-building practice in physician relationships with patients. JAMA 324, 2365–2366 (2020).

Williamson, L. D., Thompson, K. M. & Ledford, C. J. W. Trust takes two. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 35, 1179–1182 (2022).

Grob, R., Darien, G. & Meyers, D. Why physicians should trust in patients. JAMA 321, 1347–1348 (2019).

Doekhie, K. D., Strating, M. M. H., Buljac-Samardzic, M. & Paauwe, J. Trust in older persons: A quantitative analysis of alignment in triads of older persons, informal carers and home care nurses. Health Soc. Care Community 27, 1490–1506 (2019).

Taylor, L. A., Nong, P. & Platt, J. Fifty years of trust research in health care: A synthetic review. Milbank Q. 101, 126–178 (2023).

Sun, J. J. et al. Research on management of doctor-patient risk and status of the perceived behaviors of physician trust in the patient in China: New perspective of management of doctor-patient risk. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2145029 (2020).

He, Q., Li, Y., Wu, Z. & Su, J. Explicating the cognitive process of a physician’s trust in patients: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 14446 (2022).

Baker, D. W. Trust in health care in the time of COVID-19. JAMA 324, 2373 (2020).

Campos-Castillo, C. & Anthony, D. Situated trust in a physician: Patient health characteristics and trust in physician confidentiality. Sociol. Q. 60, 559–582 (2019).

Banerjee, A. & Sanyal, D. Dynamics of doctor-patient relationship: A cross-sectional study on concordance, trust, and patient enablement. J. Fam. Community Med. 19, 12–19 (2012).

Calnan, M. & Rowe, R. Trust Matters in Health Care (Open University Press, 2008). https://books.google.pl/books?id=09xEBgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=pl#v=onepage&q&f=false

Park, I. J., Kim, P. B., Hai, S. & Dong, L. Relax from job, Don’t feel stress! The detrimental effects of job stress and buffering effects of coworker trust on burnout and turnover intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 559–568 (2020).

Dworkin, A. G. & Tobe, P. F. The effects of standards based school accountability on teacher burnout and trust relationships: A longitudinal analysis. In Trust and School Life: The Role of Trust for Learning, Teaching, Leading, and Bridging (eds Van Maele, D. et al.) 121–143 (Springer, 2014).

Özgür, G. & Tektaş, P. An examination of the correlation between nurses’ organizational trust and burnout levels. Appl. Nurs. Res. 43, 93–97 (2018).

Costello, A. B. & Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 10, 1–9 (2005).

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V. & Kacmar, C. Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 13, 334–359 (2002).

Yamagishi, T. & Yamagishi, M. Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv. Emot. 18, 129–166 (1994).

Demerouti, E. & Bakker, A. B. The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory: A Good Alternative to Measure Burnout (and Engagement) (2007).

Pejtersen, J. H., Kristensen, T. S., Borg, V. & Bjorner, J. B. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand. J. Public Health. 38, 8–24 (2010).

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J. & Swann, W. B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 37, 504–528 (2003).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis 785 (2010).

Çelen, Ü. & Aybek, E. C. A novel approach for calculating the item discrimination for Likert type of scales. Int. J. Assess. Tools in Educ. 9, 772–786 (2022).

Orozco, T. et al. Development and validation of an end stage kidney disease awareness survey: Item difficulty and discrimination indices. PLoS ONE 17, e0269488 (2022).

Oosterhof, A. C. Similarity of various item discrimination indices. J. Educ. Meas. 13, 145–150 (1976).

Niño-Zarazúa, M. Quantitative Analysis in Social Sciences: An Brief Introduction for Non-Economists. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2066058 (2012).

Pilgrim, D., Tomasini, F. & Vassilev, I. Examining Trust in Healthcare: A Multidisciplinary Perspective (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010).

Cook, K. S., Levi, M. & Hardin, R. Whom Can We Trust? How Groups, Networks, and Institutions Make Trust Possible (Russell Sage Foundation, 2009). https://books.google.pl/books?id=YZzH7ftmBscC&printsec=frontcover&hl=pl#v=onepage&q&f=false

Hajjar, S. T. et al. Statistical analysis: Internal-consistency reliability and construct validity. Int. J. Quant. Qual. Res. Meth. 6, 46–57 (2018).

Domino, G. & Domino, M. L. Psychological Testing: An Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Natalie Pośpiech (MD from the University Teaching Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine, Occupational Medicine, and Hypertension in Wroclaw, Poland) for tremendous help with the translation procedure, as well as her insightful comments on the first draught of this manuscript. We are also very grateful to all 307 medical doctors who decided to share their time and participate in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. A.K.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Błaszyk, M.A., Kroemeke, A. Polish adaptation, psychometric properties and validation of Physician’s Trust in the Patient Scale (PTPS). Sci Rep 14, 18457 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69351-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69351-1

- Springer Nature Limited