Abstract

The mucus surface layer serves vital functions for scleractinian corals and consists mainly of carbohydrates. Its carbohydrate composition has been suggested to be influenced by environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, nutrients) and microbial pressures (e.g., microbial degradation, microbial coral symbionts), yet to what extend the coral mucus composition is determined by phylogeny remains to be tested. To investigate the variation of mucus carbohydrate compositions among coral species, we analyzed the composition of mucosal carbohydrate building blocks (i.e., monosaccharides) for five species of scleractinian corals, supplemented with previously reported data, to discern overall patterns using cluster analysis. Monosaccharide composition from a total of 23 species (belonging to 14 genera and 11 families) revealed significant differences between two phylogenetic clades that diverged early in the evolutionary history of scleractinian corals (i.e., complex and robust; p = 0.001, R2 = 0.20), mainly driven by the absence of arabinose in the robust clade. Despite considerable differences in environmental conditions and sample analysis protocols applied, coral phylogeny significantly correlated with monosaccharide composition (Mantel test: p < 0.001, R2 = 0.70). These results suggest that coral mucus carbohydrates display phylogenetic dependence and support their essential role in the functioning of corals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The metazoan surface mucus layer (SML) is an outermost protective barrier of exposed tissues1, and first evolved in Cnidarians and Ctenophores2. Mucus consists largely of water (95%) and mucin glycoproteins (~ 3%), which have a high (50–90%) carbohydrate content in the form of glycans (oligo- and polysaccharides) attached to a protein backbone3, giving mucus its viscoelastic properties2. Traditionally, mucus has been considered to serve important functions in metazoan defense, feeding and locomotion4. Moreover, its role in controlling associated microbial communities is increasingly recognized2. Constant renewal of the SML serves a physical antimicrobial function2,5, and chemical defenses include adhesion (entrapment) or the prevention of adhesion (dispersal) of microbes to mucin glycans2,6. Changes in mucin glycan structures can reduce antimicrobial functions of mucus7,8, and may lead to disease9, highlighting the importance of mucosal carbohydrates for metazoan health.

Corals are considered model systems for metazoan evolution2,10,11, and scleractinian corals in particular are ecologically important due to their role as ecosystem engineers of tropical as well as cold water coral reefs12,13. Mucus serves especially diverse functions in corals compared to other invertebrates14, including protection against environmental stressors (e.g., desiccation, UV radiation, and sediment smothering), supplementation of calcification, and quenching of potentially harmful oxygen radicals (reviewed by Brown and Bythell14), as well as colonial integration through mucus-coordinated surface flows15. Despite these important functions of coral mucus, little is known about the composition of coral mucus glycans, nor their phylogenetic variation.

The structural analysis of glycans is challenging due to the lack of distinct spectroscopic signatures16, and mass spectra of mucin-type glycans are especially complex and notoriously difficult to interpret17. To our best knowledge, only two studies investigated the structure of coral mucus glycans in detail through mass spectrometry of oligosaccharides cleaved from the protein backbone of mucins18,19. A less challenging and more commonly used method for total carbohydrate analysis is the measurement of monosaccharide building blocks after acid hydrolysis of glycans though chromatographic methods20, which provides insight into the composition of carbohydrates at the cost of losing structural information16. Scleractinian corals from different geographic locations displayed common mucus monosaccharides21, and Wild et al.22 found conserved monosaccharide compositions of coral mucus glycans on the genus level in Acropora and Fungia.

Phylogenetic dependence (i.e., related species resemblance) is often low for carbohydrates23,24, due to the constant selection pressure from co-evolving pathogens25 and microbial degradation26 (i.e., Red Queen effect/arms race). In addition, several factors can contribute to inter- and intraspecific variation in coral mucus. Firstly, coral mucus release rates and/or compositions can be influenced by environmental variables like water temperature27,28,29 and nutrient enrichment30. Secondly, microbial communities associated with coral mucus can vary with environmental conditions31, potentially resulting in composition adaptations. Finally, endosymbiotic dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae32 are majorly involved in mucus production33,34,35, and likely contribute to shaping mucus composition36,37.

This raises the question whether the previously suggested phylogenetic dependence in coral mucus carbohydrate compositions is limited to the genus level (e.g., as previously shown for Acropora and Fungia)22, or if it also applies to broader taxonomic groups. Scleractinian corals diverged into two main clades (i.e., “complex”, and “robust”) about 418 million years ago38, which have few morphological differences, but differ in some biosynthetic pathways39,40. We hypothesized that (1) mucus carbohydrate compositions are most different between the complex and robust clade and that (2) the phylogeny of scleractinian corals correlates with the composition of coral mucus carbohydrates, indicative for phylogenetic dependence. For the investigation, we analyzed the monosaccharide composition of hydrolized mucus glycans from five species of scleractinian corals (i.e., Acropora cervicornis, Diploria labyrinthiformis, Meandrina meandrites: collected in situ in the Caribbean; Montipora digitata, and Montipora confusa: grown ex situ in Bremen, Germany) and combined our results with reported literature data (total of 23 species from 14 genera and 11 families).

Results

Monosaccharide composition of mucosal carbohydrates

The monosaccharide compositions of mucosal carbohydrates of the five species analyzed in the present study (i.e., A. cervicornis, D. labyrinthiformis, M. meandrites: collected in situ on Curaçao and maintained in ambient seawater; M. confusa, M. digitata: grown in aquarium facilities in Bremen, Germany) revealed a common presence of glucosamine (GlcN) in all analyzed samples, and an absence of rhamnose (Rha), while all other monosaccharides (galactosamine, GalN; xylose, Xyl; galactose, Gal; fucose, Fuc; glucose, Glc; mannose, Man; arabinose, Ara) were only present in certain species (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). The two Indo-Pacific sister species M. confusa and M. digitata had almost identical mucus carbohydrate compositions of GlcN (54.0 ± 1.6 and 56.9 ± 2.8 mol%) and Ara (46.0 ± 1.6 and 43.1 ± 2.8 mol%), while mucus carbohydrate compositions of D. labyrinthiformis and M. meandrites differed from A. cervicornis, due to high relative contribution of Fuc (47.8 ± 1.1 and 33.6 ± 7.1 vs. 2.0 ± 0.4 mol%) to total carbohydrates (see mean concentrations in Table 1). The total carbohydrate concentration of mucus from A. cervicornis was 9 to 16 times higher compared to the other species (ANOVA: F(4, 9) = 59.2, η2 = 0.96, p < 0.001; Tukey HSD: p < 0.001), which enabled the detection of monosaccharides with low relative abundance.

Cluster analysis including literature data

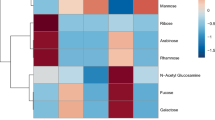

Hierarchical cluster analysis including data from the present study (Table 1) and six previous studies (Supplementary Table S2) revealed three significantly different clusters (PERMANOVA: F(2) = 12.9, p = 0.001; all pairwise comparisons: p = 0.003, Bonferroni adjusted; Figs. 1 and 2a) which explained 51% of variance. Overall, the monosaccharides GlcN / N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc), Ara, Man, and Glc were the most common, and GalN / N-acetyl galactosamine (GalNAc) and Rha were the least common components of coral mucus carbohydrates (Fig. 1). The difference between corals of the complex and robust clade alone was also significant and explained 20% of the observed variance (PERMANOVA: F(1) = 7.9, p = 0.001; Figs. 1 and 2b). Monosaccharide compositions did not differ between studies (PERMANOVA: F(4) = 3.2, p = 0.033; all pairwise comparisons: p > 0.05; Fig. 2c), nor between geographic regions where the coral specimen originated from (PERMANOVA: F(3) = 2.5, p = 0.007; all pairwise comparisons: p > 0.05; Fig. 2d).

Coral mucus carbohydrate compositions form three significantly different clusters. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap of relative monosaccharide compositions per coral species (mole % values are given in cells), measured in the present study and six previous studies (see Supplementary Table S2 for more detail). Dendrogram is based on Euclidean distance. GalN/GalNAc = galactosamine/N-acetyl-galactosamine, Xyl = xylose, Rha = rhamnose, Gal = galactose, Fuc = fucose, Glc = glucose, Man = mannose, Ara = arabinose, GlcN/GlcNAc = glucosamine /N-acetyl-glucosamine.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling of coral mucus carbohydrate compositions divided by (a) clusters established in hierarchal cluster analysis (see Fig. 1), (b) phylogenetic clade, (c) study where the data originated, and (d) geographic origin of specimen. Vectors for monosaccharides were only shown when significant (p < 0.05). All factors were significant in permutational multivariate analysis of variance, but only a and b revealed significant differences between groups in pairwise comparisons (pairwiseAdonis, p < 0.05). Plus-signs mark centroids of respective groups, and ellipses mark areas of 68% confidence. Fuc = fucose, Glc = glucose, Man = mannose, Ara = arabinose, GlcN/GlcNAc = glucosamine /N-acetyl-glucosamine.

The first cluster exclusively included coral species of the complex clade, covering three families and four genera, and all reported measurements of the family Acroporidae (Fig. 1). The cluster was characterized by significantly more Ara compared to the two other clusters (p < 0.01, Dunn’s test, Bonferroni adjusted; see Fig. 3 for all Kruskal–Wallis test results), and significantly more GlcN compared to the third cluster (p < 0.05).

Characterization of the three clusters from hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. 1). Comparison of relative monosaccharide contents among clusters. Asterisks indicate significant differences between clusters (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Dunn’s test, Bonferroni adjusted), where Kruskal Wallis tests were significant (results reported on the bottom of the respective panel). Boxes represent the interquartile range, with the horizontal black line indicating the median, and black crosses indicating the mean. GalN/GalNAc = galactosamine / N-acetyl-galactosamine, Xyl = xylose, Rha = rhamnose, Gal = galactose, Fuc = fucose, Glc = glucose, Man = mannose, Ara = arabinose, GlcN/GlcNAc = glucosamine /N-acetyl-glucosamine.

The second cluster was only composed of corals from the robust clade, covering five families and six genera, including all three measurements of the family Fungiidae (Fig. 1). Mucus carbohydrates contained significantly more Fuc than the two other clusters (p < 0.05), and significantly more GlcN than the third cluster (p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

The third cluster included all species of the family Pocilloporidae, as well as two other families of the robust clade, and Galaxea fascicularis of the complex clade (Fig. 1). Mucus carbohydrates contained significantly more Man (p < 0.05) and Glc (p < 0.05) than the other clusters (Fig. 3).

Correlation between coral mucus carbohydrate composition and coral phylogeny

To quantify the correlation of scleractinian coral phylogeny on coral mucus carbohydrate composition, we created a phylogenetic tree including the same species (or close sister species) used in the dendrogram for carbohydrate compositions (i.e., Fig. 1). Both dendrograms were connected with lines for visual comparison (Fig. 4), and a Mantel test was used to compare the two distance matrices, revealing a significant correlation (R = 0.70, p = 0.001, 999 permutations). The three clusters from the carbohydrate dendrogram were mostly reflected by the phylogenetic tree, with the exception of Desmophyllum sp. (Norway) and G. fascicularis (see grey dashed lines in Fig. 4).

Mucus carbohydrate composition (left dendrogram, derived from Fig. 1) and phylogenetic tree (right dendrogram, based on cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI)) correlate significantly. Result of the Mantel test is given on the bottom, where the simulated p value is based on 999 permutations. Colors of connecting lines highlight the three main clusters of the left dendrogram. Bold lines indicate closely related species with high similarity in mucus compositions (i.e., high correlation). Grey dashed lines indicate species where the mucus carbohydrate composition reflects a different cluster compared to closely related species (i.e., low correlation). Symbols represent different scleractinian coral genera and are added for illustrational purposes. Symbol attribution: Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/media-library), CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

For closely related species, relationships between phylogeny and mucus carbohydrate composition were more variable than on the broader taxonomic scale. Orbicella annularis and D. labyrinthiformis, Stylophora pistillata and Pocillopora verrucosa, as well as M. digitata and M. confusa were highly correlated (see bold connecting lines in Fig. 4). However, differences in mucus carbohydrate composition within the genera Desmophyllum, Fungia, and Pocillopora were greater than differences between closely related families (i.e., Merulinidae and Faviidae). In addition, the three available carbohydrate measurements of mucus from Acropora muricata (from three different studies) displayed as much variation as was observed on the family level within the Acroporidae.

Discussion

Hierarchical cluster analysis of the combined data on coral mucus carbohydrate compositions of 23 scleractinian coral species and 11 families revealed three significantly different clusters (Figs. 1 and 2a), due to differences in the monosaccharides Ara, Fuc, GlcN/GlcNAc, Glc, and Man (Fig. 3). The absence of Ara in the robust clade mainly contributed to a significant difference between complex and robust corals, a pattern which could not be explained by differences between geographic regions where the specimen originated, nor between studies which first reported the data (Fig. 2). Finally, the dendrogram containing the three clusters correlated significantly with the phylogenetic tree of scleractinian corals (Fig. 4).

Coral mucus carbohydrate composition may display phylogenetic dependence

Results of the present study revealed a significant correlation between coral mucus carbohydrate composition and coral phylogeny, which is more apparent at a broad taxonomic scale (i.e., between the complex and robust clades) and may indicate phylogenetic dependence of the mucosal carbohydrate building blocks (i.e., monosaccharides). Phylogenetic dependence (or phylogenetic signal) is the trend of traits being more similar between more closely related species, and can be explained by genetic drift25. Random mutations are suggested to lead to increasing differences in genes with increasing phylogenetic distance (i.e., the timespan since divergence of lineages)23.

Meikle et al.19, one of the few studies that analyzed the detailed glycan structure of coral mucus, revealed that mucins of A. muricata (then A. formosa41) are highly glycosylated through O-glycosidic links, and glycan side chains rich in Ara, Man, and GlcNAc. These same monosaccharides (i.e., Ara, Man, and GlcN/GlcNAc) were common in mucus of all Acropora species analyzed in the present study (Fig. 1) and were thus likely parts of mucins. The protein backbone of mucins (encoded by MUC genes) dictates the position of O-glycans, which can only be attached to the hydroxyl groups of serine or threonine42. The MUC genes differ between branches of the tree of life43, and evolutionary variation of the regions where glycosylation occurs can lead to structural and functional changes of mucins44. Thus, the correlation of coral mucus carbohydrate composition and coral phylogeny may indicate phylogenetic dependence in MUC genes and/or genes for enzymes involved in glycosylation. This connection could be further investigated by studying the involved genes (i.e., MUC and GT) in scleractinian corals.

Glycan structures and compositions usually do not reflect phylogenetic lineages, as glycans evolve rapidly to escape pathogens23 and general microbial degradation26 (i.e., Red Queen effect/arms race). For example, Tao et al.24 proposed that rather than phylogeny, selective environmental and microbial pressures shape oligosaccharide compositions (carbohydrates composed of several monosaccharides) in primate milk. Variation of host glycans is limited by the necessity to retain vital functions45 such as successful interactions with microbial symbionts23. Thus, phylogenetic dependence of carbohydrate compositions may contribute to conserving vital functions for scleractinian corals. However, monosaccharide compositions of hydrolyzed glycans lack information on the overall glycan structure16, and future studies should aim to capture their full molecular variation (e.g., as proposed by Bligh et al.26).

Phylogenetic dependence despite various environmental and microbial pressures

The three mucus carbohydrate compositions of A. muricata used in this analysis originated from Taiwan27 and the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) in Australia46,47 and revealed large differences. These differences could be explained by different environmental conditions, as water temperature was shown to influence coral mucus carbohydrate composition in A. muricata27. On the other hand, Klaus et al. (2007) found no intra-specific variation across depth- and coastal pollution gradients in mucus carbohydrates of M. annularis48. Thus, more research is needed to elucidate the species-specific effects of environmental factors on coral mucus carbohydrate compositions. Furthermore, changes in microbial communities due to environmental conditions31 and ex situ culturing49,50 (i.e., for M. digitata and M. confusa colonies in the present study) may influence coral mucus compositions, and thus should be included in future studies due to expected interaction of mucosal carbohydrates with associated microbes9,51. Lastly, endosymbiotic Symbiodiniaceae likely influence coral mucus compositions36,37 and the taxonomic composition of Symbiodiniaceae communities can vary widely among and within species of scleractinian corals52,53. We did not analyze the Symbiodiniaceae communities associated with the investigated corals in the present study, so we do not know which taxa of endosymbionts were present. But, Symbiodiniaceae-coral associations for 64 species of 18 genera of hard corals (including the genera Acropora, Galaxea, Pocillopora, Pachyseris, Porites and Montipora included in the present study) differed between species, while they did not depend on phylogenetic clades (i.e., complex or robust)54. Arabinose is not common in animal cells46,55, and may be delivered to the coral host by the endosymbiotic dinoflagellates22,46. Arabinose characterized the mucus of corals from the complex clade, the only exception to this trend being G. fascicularis. The origin of Ara in the mucus of corals from the complex clade should be further investigated and studying the mucus Ara content in response to coral bleaching, or differences in dominant Symbiodiniaceae genera could reveal a link to Symbiodiniaceae metabolism. Subsequently, it could be expected that theses environmental and microbial pressures largely determine the variation in mucus carbohydrate composition and thereby overrule potential effects of phylogeny. Surprisingly, in the present study the opposite appears to be the case with coral phylogeny explaining 70% of the observed variation on the level of monosaccharide building blocks in coral mucus glycans.

Potential caveats and limitations

Apart from the aforementioned potential effects of variations in environmental conditions, geographic locations, and ex situ vs in situ collections, the use of different sampling protocols and analytical methods have likely affected the mucus carbohydrate compositions reported in the different studies which were included in the cluster analysis (Supplementary Table S3). Coral mucus sampling was conducted either by drawing mucus from the corals’ surface with low stress21,48, or by removing the coral from water and catching the dripping mucus (i.e., “milking”22,27,47; and present study), which induces stress and may impact mucus compositions14. Next to mucins, mucus collected with this method may contain seawater released from the coelenteron and tissue debris56. Nevertheless, “milking” is an efficient way to collect relatively pure mucus samples (i.e., without environmental contamination) from corals, and is also used frequently in microbial ecology57,58,59. Additionally, carbohydrate analysis was conducted either by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC–MS)21,22,46,47, high-performance liquid chromatography with MS detection (HPLC–MS)27, or high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD48; and present study). GC–MS requires chemical alteration of sugar molecules, while HPAEC-PAD does not require this step and has a lower detection range, making it more suitable for environmental samples60. As coral mucus carbohydrate concentrations are generally high, the difference in detection limit between methods may be negligible, and differences in accuracy between methods are less relevant when comparing relative compositions (i.e., mol%). Furthermore, dialysis membranes used for desalination of mucus samples ranged in pore size between 0.1 and 50 kDa, and no dialysis was carried out in the present study where samples were diluted instead. The majority of carbohydrates in coral mucus are in the form of mucin glycoproteins and large heteropolysaccharides which have molecular sizes of 175–30,000 kDa18,56,61. Thus, these molecules should have remained in the samples with any of the used pore sizes. Finally, we acknowledge the limited number of replicates for some of the analyzed coral species, which was one for some of the early measurements46, and two to three for our analyses (more detail in Supplementary Table S2). Despite the potential effects of these limitations, we would like to point out that there was no significant effect of study on the monosaccharide composition (Fig. 2c). In combination with the fact that 70% of the observed variation in monosaccharide composition could be explained by coral phylogeny, this may indicate the dominating effect of phylogeny on the composition of monosaccharide building blocks in coral mucus carbohydrates.

Conclusion

The carbohydrate compositions of coral mucus from 23 species originated from seven different studies (including the present study), and were thus likely influenced by (i) differences in environmental conditions (including in situ vs ex situ growth), (ii) associated microbiota, and (iii) sample preparation- and measurement methods. Despite these factors which can induce variation, the mucus compositions from corals of the complex and robust clade were significantly different, and coral phylogeny explained 70% of the variation. Therefore, our results indicate that coral mucus carbohydrate composition exhibits phylogenetic dependence (on the level of their monosaccharide building blocks), suggesting important functions of mucosal carbohydrates for scleractinian corals.

Methods

Mucus collection

Fragments of the critically endangered coral species A. cervicornis (n = 3) were temporarily provided by the coral restoration project Reef Renewal Curaçao to avoid any detrimental pressure on natural populations. Coral fragments were suspended on coral trees (i.e., floating pipe structures at 10 m depth) with strings and could therefore be removed and transported to the CARMABI research station without tissue damage. Colonies of D. labyrinthiformis (n = 3) and M. meandrites (n = 2) were collected from the reef in Piscadera Bay (12.121012, − 68.970380) while avoiding injury to living tissue. All corals were kept and allowed to recover for one week at a suspended artificial structure at 10 m depth in front of the CARMABI research station. Colonies were brought to a seawater flow-through aquarium in the morning, incubated in an aquarium with 22 L of filtered seawater (0.2 µm pore size) for 6 h at ambient temperature and light conditions (29.0 °C ± 0.2 SD, 101 µmol photons m−2 s−1 ± 13 SD) as part of a different study (Thobor et al., in preparation), and then again placed in the flow-through aquarium for the night. Mucus was sampled the next morning by exposing the colonies to air, and collecting the dripping mucus for two minutes in a sterile falcon tube after discarding the first 30 s, according to Wild et al.47. This method is also called “milking” of corals, and may result in different biochemical compositions of mucus than what is present in the surface layer when undisturbed14. Montipora digitata (n = 3) and M. confusa (n = 3) colonies from the Indo-Pacific were grown in the aquarium facilities of the Marine Ecology department of the University of Bremen for six years under stable conditions (water temperature: ~ 26 °C; light: ~ 100–150 µmol photons m−2 s−1; salinity: ~ 35‰; sea salt: Zoo Mix, Tropic Marin, Switzerland). Although these two species are the only ones which were not collected in situ, we decided to include them in the analysis, as the aim of the study was to investigate phylogenetic effects on mucus composition. Mucus collection was done as described above, and colonies were placed back into the aquarium. All mucus samples were stored at − 20 °C until further processing, as was done before for the analysis of carbohydrates in coral mucus samples22,27,62.

Measurement of monosaccharide compositions

Mucus samples were hydrolyzed at 100 °C for 24 h by adding 50 µL of 2 M HCl to 50 µL of mucus. Afterwards, mucus was diluted by a factor of 100 by adding 20 µL of the mucus-HCl mixture to 980 µL of ultrapure water (UW). Diluted mucus samples were vortexed, and then centrifuged (15 min at 21,100×g), and 100 µL of the top layer were transferred into glass vials for measurement together with six calibration standards including all monosaccharides at concentrations ranging from 10 to 1000 µg L−1. Monosaccharide concentrations of hydrolyzed mucus were measured with a high-performance anion exchange chromatography system (Dionex ICS-5000+, Thermo Fisher Scientific), equipped with a PA10 column (2 × 250 mm) and PA10 guard column (both by Thermo Fisher Scientific). Monosaccharides were separated by an isocratic flow of 18 mM NaOH for 20 min. HPAEC was coupled with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) as previously described20.

Data preparation for hierarchical cluster analysis

Monosaccharide concentrations measured in the present study were converted to mole %, using the mean of two (M. meandrites) or three (all other species) replicates. Data of mucus carbohydrate compositions of 23 different scleractinian coral species, measured with varying numbers of replicates ranging from one to 36 (see Table S2 for more detail) were retrieved from six previous studies21,22,27,46,47,48. Species or genera with several reported mucus compositions from different locations or studies (i.e., A. muricata, Desmophyllum sp.) were treated separately in analyses. Only studies which could detect the nine neutral and amino sugars Fuc, Rha, GalN/GalNAc, Ara, GlcN/GlcNAc, Gal, Glc, Man, and Xyl were included (see comparison of methods used in Table S3). GlcN was pooled with its derivate GlcNAc, and GalN was pooled with GalNAc. Species names were changed to the currently accepted names, i.e., “Montastrea annularis” now Orbicella annularis63, “Acropora formosa” now A. muricata41, “A. nobilis” now A. robusta41, and finally “Lophelia sp.” now Desmophyllum sp.64. Three studies21,47,48 did not report the absence of GalN/GalNAc, but values were set to zero because the methods used (Table S3) enable the detection of GalN/GalNAc. Specifically, Wild et al.22, reported the absence of GalNAc for data measured in Wild et al.47 and the GC–MS analysis in Hadaidi et al.21 were conducted by the same analytical facility as for Wild et al.22,47, thus also being able to detect GalN/GalNAc. Finally, Klaus et al.48 used HPAEC-PAD, the same method used in the present study which can detect GalN/GalNAc20. Similarly, absence of Rha was not reported in two studies27,46 although methods used (Table S3) can detect Rha, and values were set to zero. Two studies21,48 reported the relative abundance of additional monosaccharides, and mole % values were adjusted accordingly for better comparison among studies. Mole % data of Fungia sp.22 was averaged from three measurements conducted in different seasons. Finally, Stylophora sp.22 was not included in the hierarchical cluster analysis of the present study, because only one monosaccharide (Glc) was detected. This was likely due to low carbohydrate concentrations in the mucus, leading to the sole detection of one monosaccharide, which was then over-estimated as contributing to 100% of carbohydrates.

Phylogenetic tree construction

To be able to correlate the mucus carbohydrate dendrogram with coral phylogeny, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI). The COI sequences were downloaded from GenBank (see Supplementary Table S4). Sequences were loaded into Geneious Prime software (version 2023.0.3) and aligned using the Geneious Alignment tool. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on unweighted pair group with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) with Hasegawa, Kishino, and Yano (HKY) genetic distances using the Geneious Tree Builder tool. The resulting distance matrix was exported and used to create the tanglegram (see statistical analyses section). For comparisons of unspecified genera or in case a COI sequence of a selected species was not available, COI sequences of sister species within the same genus were downloaded and used to construct the phylogenetic tree (Genus species mucus dendrogram vs. Genus species phylogeny), i.e., Desmophyllum sp. vs. Desmophyllum pertusum, Ctenactis sp. vs. Ctenactis crassa, Fungia sp. vs. Fungia fungites, Pocillopora sp. vs. Pocillopora verrucosa, Madrepora sp. vs. Madrepora oculata, and finally Montipora confusa vs. Montipora undata. These substitutes were chosen as follows: only one COI sequence was available for the genera Desmophyllum, Ctenactis, and Madrepora. Montipora confusa was substituted with the available COI sequence which was most closely related, and unspecified genera which were already present in the phylogenetic tree (i.e., Fungia sp. and Pocillopora sp.) were merged with the already present species of the respective genus.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted with R version 4.3.0 and R Studio version 2023.03.1. Hierarchical clustering of mucus monosaccharide compositions was performed using the package pheatmaps and the “complete” clustering method (i.e., Euclidean distance). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, vegan package, 999 permutations) was used to test for differences in Euclidean distance matrices of carbohydrate compositions between groups (i.e., clusters, clades, studies, geographic regions), and homogeneity of dispersion among groups was tested with permutational multivariate analysis of dispersion (PERMDISP, vegan package). Homogeneity of dispersion was not given for the factors Clade and Study, but PERMANOVA is robust to heterogeneity in dispersion for balanced designs65 and sample sizes for Clade were nearly balanced (n2/n1 = 1.33). The two studies which only reported mucus compositions for one species27,48 were not included in PERMANOVA analysis for the factor Study to reduce the heterogeneity in dispersion. Distance matrices were additionally visualized with non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS, vegan package) to display the effects of Cluster, Clade, Study, and Geographic region on carbohydrate compositions. For post-hoc analysis, multiple pairwise comparisons were conducted with the R package pairwiseAdonis, Bonferroni adjustment, and 999 permutations. To test for differences in the relative abundance of single monosaccharides between the three main clusters, Kruskal–Wallis-Tests were performed, and when significant (p < 0.05), multiple pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Dunn’s test with Bonferroni adjustment. Correlation between the two distance matrices of the hierarchical cluster dendrogram and the phylogenetic tree was tested with a Mantel test (ade4 package), which is frequently used to compare phylogenetic trees and test for cophylogeny66,67. A tanglegram was created with the dendextend package68, combining the two distance matrices from mucus carbohydrate compositions and phylogenetic information. The measurement for “Acropora sp. (Red Sea)” was removed from the carbohydrate dendrogram after clustering with the prune function, as it could not be connected to a species of the phylogenetic tree.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Lai, S. K., Wang, Y.-Y., Wirtz, D. & Hanes, J. Micro- and macrorheology of mucus. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 61, 86–100 (2009).

Bakshani, C. R. et al. Evolutionary conservation of the antimicrobial function of mucus: A first defence against infection. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 4, 1–12 (2018).

Rose, M. C. & Voynow, J. A. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 86, 245–278 (2006).

Denny, M. W. Invertebrate mucous secretions: Functional alternatives to vertebrate paradigms. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 43, 337–366 (1989).

Wild, C. et al. Coral mucus functions as an energy carrier and particle trap in the reef ecosystem. Nature 428, 66–70 (2004).

McLoughlin, K., Schluter, J., Rakoff-Nahoum, S., Smith, A. L. & Foster, K. R. Host selection of microbiota via differential adhesion. Cell Host Microbe 19, 550–559 (2016).

Wheeler, K. M. et al. Mucin glycans attenuate the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in infection. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 2146–2154 (2019).

Xia, B., Royall, J. A., Damera, G., Sachdev, G. P. & Cummings, R. D. Altered O-glycosylation and sulfation of airway mucins associated with cystic fibrosis. Glycobiology 15, 747–775 (2005).

Belzer, C. Nutritional strategies for mucosal health: The interplay between microbes and mucin glycans. Trends Microbiol. 30, 13–21 (2022).

Miller, D. J. & Ball, E. E. The coral Acropora: What it can contribute to our knowledge of metazoan evolution and the evolution of developmental processes. BioEssays 22, 291–296 (2000).

Technau, U. & Steele, R. E. Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: Cnidaria. Development 138, 1447–1458 (2011).

Wild, C. et al. Climate change impedes scleractinian corals as primary reef ecosystem engineers. Mar. Freshw. Res. 62, 205 (2011).

Woodhead, A. J., Hicks, C. C., Norström, A. V., Williams, G. J. & Graham, N. A. J. Coral reef ecosystem services in the anthropocene. Funct. Ecol. 33, 1023–1034 (2019).

Brown, B. E. & Bythell, J. C. Perspectives on mucus secretion in reef corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 296, 291–309 (2005).

Bouderlique, T. et al. Surface flow for colonial integration in reef-building corals. Curr. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.054 (2022).

Arnosti, C. et al. The biogeochemistry of marine polysaccharides: Sources, inventories, and bacterial drivers of the carbohydrate cycle. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 13, 81–108 (2021).

Grabarics, M. et al. Mass spectrometry-based techniques to elucidate the sugar code. Chem. Rev. 122, 7840–7908 (2022).

Coddeville, B., Maes, E., Ferrier-Pagès, C. & Guerardel, Y. Glycan profiling of gel forming mucus layer from the scleractinian symbiotic coral Oculina arbuscula. Biomacromolecules 12, 2064–2073 (2011).

Meikle, P., Richards, G. N. & Yellowlees, D. Structural determination of the oligosaccharide side chains from a glycoprotein isolated from the mucus of the coral Acropora formosa. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 16941–16947 (1987).

Engel, A. & Händel, N. A novel protocol for determining the concentration and composition of sugars in particulate and in high molecular weight dissolved organic matter (HMW-DOM) in seawater. Mar. Chem. 127, 180–191 (2011).

Hadaidi, G., Gegner, H. M., Ziegler, M. & Voolstra, C. R. Carbohydrate composition of mucus from scleractinian corals from the central Red Sea. Coral Reefs 38, 21–27 (2019).

Wild, C., Naumann, M., Niggl, W. & Haas, A. Carbohydrate composition of mucus released by scleractinian warm- and cold-water reef corals. Aquat. Biol. 10, 41–45 (2010).

Bishop, J. R. & Gagneux, P. Evolution of carbohydrate antigens—Microbial forces shaping host glycomes?. Glycobiology 17, 23R-34R (2007).

Tao, N. et al. Evolutionary glycomics: Characterization of milk oligosaccharides in primates. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1548–1557 (2011).

Blomberg, S. P. & Garland, T. Jr. Tempo and mode in evolution: phylogenetic inertia, adaptation and comparative methods. J. Evol. Biol. 15, 899–910 (2002).

Bligh, M., Nguyen, N., Buck-Wiese, H., Vidal-Melgosa, S. & Hehemann, J.-H. Structures and functions of algal glycans shape their capacity to sequester carbon in the ocean. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 71, 102204 (2022).

Lee, S. T. M., Davy, S. K., Tang, S.-L. & Kench, P. S. Mucus sugar content shapes the bacterial community structure in thermally stressed Acropora muricata. Front. Microbiol. 7, 371 (2016).

Niggl, W., Glas, M., Laforsch, C., Mayr, C. & Wild, C. First evidence of coral bleaching stimulating organic matter release by reef corals. Proc. 11th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 905–911 (2009).

Wright, R. M., Strader, M. E., Genuise, H. M. & Matz, M. Effects of thermal stress on amount, composition, and antibacterial properties of coral mucus. PeerJ 7, e6849 (2019).

Quinlan, Z. A. et al. Fluorescent organic exudates of corals and algae in tropical reefs are compositionally distinct and increase with nutrient enrichment. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 3, 331–340 (2018).

Voolstra, C. R. & Ziegler, M. Adapting with microbial help: microbiome flexibility facilitates rapid responses to environmental change. BioEssays 42, 2000004 (2020).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 28, 2570-2580.e6 (2018).

Crossland, C. J. In situ release of mucus and DOC-lipid from the corals Acropora variabilis and Stylophora pistillata in different light regimes. Coral Reefs 6, 35–42 (1987).

Crossland, C. J., Barnes, D. J. & Borowitzka, M. A. Diurnal lipid and mucus production in the staghorn coral Acropora acuminata. Mar. Biol. 60, 81–90 (1980).

Davies, P. S. The role of zooxanthellae in the nutritional energy requirements of Pocillopora eydouxi. Coral Reefs 2, 181–186 (1984).

Banin, E., Israely, T., Fine, M., Loya, Y. & Rosenberg, E. Role of endosymbiotic zooxanthellae and coral mucus in the adhesion of the coral-bleaching pathogen Vibrio shiloi to its host. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 199, 33–37 (2001).

Sivaguru, M. et al. Corals regulate the distribution and abundance of Symbiodiniaceae and biomolecules in response to changing water depth and sea surface temperature. Sci. Rep. 11, 2230 (2021).

Arrigoni, R. et al. A new sequence data set of SSU rRNA gene for Scleractinia and its phylogenetic and ecological applications. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, 1054–1071 (2017).

Shinzato, C. et al. Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change. Nature 476, 320–323 (2011).

Ying, H. et al. Comparative genomics reveals the distinct evolutionary trajectories of the robust and complex coral lineages. Genome Biol. 19, 175 (2018).

Veron, J. E. N. Corals of Australia and the Indo-Pacific. (Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1986).

Corfield, A. P. & Berry, M. Glycan variation and evolution in the eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 351–359 (2015).

Lang, T. et al. Searching the evolutionary origin of epithelial mucus protein components—Mucins and FCGBP. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1921–1936 (2016).

Xu, D. et al. Recent evolution of the salivary mucin MUC7. Sci. Rep. 6, 31791 (2016).

Gagneux, P. & Varki, A. Evolutionary considerations in relating oligosaccharide diversity to biological function. Glycobiology 9, 747–755 (1999).

Meikle, P., Richards, G. N. & Yellowlees, D. Structural investigations on the mucus from six species of coral. Mar. Biol. 99, 187–193 (1988).

Wild, C., Woyt, H. & Huettel, M. Influence of coral mucus on nutrient fluxes in carbonate sands. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 287, 87–98 (2005).

Klaus, J. S., Janse, I., Heikoop, J. M., Sanford, R. A. & Fouke, B. W. Coral microbial communities, zooxanthellae and mucus along gradients of seawater depth and coastal pollution. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 1291–1305 (2007).

Kooperman, N., Ben-Dov, E., Kramarsky-Winter, E., Barak, Z. & Kushmaro, A. Coral mucus-associated bacterial communities from natural and aquarium environments. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 276, 106–113 (2007).

Pratte, Z. A., Richardson, L. L. & Mills, D. K. Microbiota shifts in the surface mucopolysaccharide layer of corals transferred from natural to aquaria settings. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 125, 42–44 (2015).

Wu, C. M. et al. Mucin glycans drive oral microbial community composition and function. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 1–14 (2023).

Marzonie, M. R., Nitschke, M. R., Bay, L. K., Bourne, D. G. & Harrison, H. B. Symbiodiniaceae diversity varies by host and environment across thermally distinct reefs. Mol. Ecol. 33, e17342 (2024).

de Souza, M. R. et al. Community composition of coral-associated Symbiodiniaceae differs across fine-scale environmental gradients in Kāne‘ohe Bay. R. Soc. Open Sci. 9, 212042 (2022).

Lee, L. K. et al. Molecular diversity and assemblages of coral symbionts (Symbiodiniaceae) in diverse scleractinian coral species. Mar. Environ. Res. 179, 105706 (2022).

Mariette, A. et al. Not just a simple sugar: arabinose metabolism and function in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 62, 1791–1812 (2021).

Jatkar, A. A. et al. Coral mucus: The properties of its constituent mucins. Biomacromolecules 11, 883–888 (2010).

Glasl, B., Herndl, G. J. & Frade, P. R. The microbiome of coral surface mucus has a key role in mediating holobiont health and survival upon disturbance. ISME J. 10, 2280–2292 (2016).

Lee, S. T. M., Davy, S. K., Tang, S.-L., Fan, T.-Y. & Kench, P. S. Successive shifts in the microbial community of the surface mucus layer and tissues of the coral Acropora muricata under thermal stress. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91, fiv142 (2015).

Koenig, J. E. et al. Coral-mucus-associated Vibrio integrons in the Great Barrier Reef: Genomic hotspots for environmental adaptation. ISME J. 5, 962–972 (2011).

Panagiotopoulos, C. & Sempéré, R. Analytical methods for the determination of sugars in marine samples: A historical perspective and future directions. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 3, 419–454 (2005).

Bythell, J. C. & Wild, C. Biology and ecology of coral mucus release. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 408, 88–93 (2011).

Nelson, C. E. et al. Coral and macroalgal exudates vary in neutral sugar composition and differentially enrich reef bacterioplankton lineages. ISME J. 7, 962–979 (2013).

Veron, J. E. N. Corals of the World. vols 1–3 (Australian Institute of Marine Science and CRR, Queensland, 2000).

Addamo, A. M. et al. Merging scleractinian genera: the overwhelming genetic similarity between solitary Desmophyllum and colonial Lophelia. BMC Evol. Biol. 16, 108 (2016).

Anderson, M. J. & Walsh, D. C. I. PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing?. Ecol. Monogr. 83, 557–574 (2013).

Mazel, F. et al. Is host filtering the main driver of phylosymbiosis across the tree of life?. mSystems 3, e00097-18 (2018).

Pollock, F. J. et al. Coral-associated bacteria demonstrate phylosymbiosis and cophylogeny. Nat. Commun. 9, 4921 (2018).

Galili, T. dendextend: An R package for visualizing, adjusting and comparing trees of hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 31, 3718–3720 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Milou Arts for assisting with the collection of coral specimens which were later returned to the reef. We thank Bert Hoeksema and Christian Voolstra for their valuable input concerning the construction of the phylogenetic tree. We also thank Nicola Steinke, Silvia Vidal-Melgosa and Alek Bolte for their help and guidance with the HPAEC-PAD analyses of mucus samples.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.T. and A.T. analyzed the data. J.-H.H. provided resources and technical support. B.T. collected the data, prepared the figures and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors conceptualized, read and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thobor, B.M., Tilstra, A., Mueller, B. et al. Mucus carbohydrate composition correlates with scleractinian coral phylogeny. Sci Rep 14, 14019 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64828-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64828-5

- Springer Nature Limited