Abstract

Morbidity and mortality from several diseases are increased on days of higher ambient air pollution. We carried out a daily time-series analysis with distributive lags to study the influence of short-term air pollution exposure on COVID-19 related hospitalization in Santiago, Chile between March 16 and August 31, 2020. Analyses were adjusted for temporal trends, ambient temperature, and relative humidity, and stratified by age and sex. 26,579 COVID-19 hospitalizations were recorded of which 24,501 were laboratory confirmed. The cumulative percent change in hospitalizations (95% confidence intervals) for an interquartile range increase in air pollutants were: 1.1 (0.2, 2.0) for carbon monoxide (CO), 0.30 (0.0, 0.50) for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and 2.7 (1.9, 3.0) for particulate matter of diameter ≤ 2.5 microns (PM2.5). Associations with ozone (O3), particulate matter of diameter ≤ 10 microns (PM10) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) were not significant. The observed effect of PM2.5 was significantly greater for females and for those individuals ≥ 65 years old. This study provides evidence that daily increases in air pollution, especially PM2.5, result in a higher observed risk of hospitalization from COVID-19. Females and the elderly may be disproportionately affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

On April 21, 2024 WHO reported 775,364,261 confirmed COVID-19 cases, including 7,046,320 confirmed deaths globally1. In the United States alone, a total of 103,436,829 confirmed COVID-19 cases, as well as 1,186,079 deaths due to COVID-19 were recorded as of April 20242. In Chile, since the start of the pandemic to December 19, 2023, there have been 5,339,561 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 62,669 confirmed COVID-19 related deaths1.

Apart from host and virus-related characteristics that increase the risk of COVID-19 morbidity3,4,5,6,7, previous population-based studies suggest that ambient air pollution may be a risk factor for COVID-19 related hospitalization8,9,10. Most of these studies compared hospitalization rates with long-term exposure in different geographic regions9,11,12,13,14. Findings are susceptible to confounding by differences between the populations being compared, which may include: age, sex, burden of comorbidities, social deprivation15, population density16, climate17, and access to health care17,18. Confounding by differences between study groups can be largely avoided by using a time-series analysis design15,19,20, which can test the association between day-to-day changes in air pollution, and day-to-day changes in hospitalization or mortality rates in the same population. This model assumes that population characteristics do not change on a very short-term basis, and both measured and unmeasured risk factors remain stable between higher and lower air pollution concentration days. One possible confounding factor could be weather, which changes day-to-day and may be associated with overall air quality.

As part of a recent review of air pollution and COVID-19, Hernandez Carballo et al. (2022), evaluated 17 publications, based on 11 studies of hospitalization or non-fatal severity. Seven were classified as having positive results, eight had mixed results, and two were classified as having non-significant results9. The majority of studies reported health effects from exposure to ambient fine particulate matter with particle diameter of 2.5 µm or less (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). One study assessed health effects from exposure to ambient ozone (O3) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) pollutants. Most studies were based on spatial differences in morbidity and only a minority of studies used a time-series design. A daily time-series study in 2020 reported that NO2 was positively associated with COVID-19 related hospitalizations in six of nine Spanish regions, and fine particulate matter with particle diameter of 10 µm or less (PM10) in four Spanish regions21. Another population-based study done in 2020, using simple correlation coefficients found that a 5-day moving average of daily mean PM2.5 levels lagged by 20 days was positively associated with critical care admissions in Florence and Milan, but not in Trento province17. Diaz et al. (2021) reported that hospitalizations in 2020 in Madrid were higher on days of higher NO2 concentrations, but not on days of higher PM10 concentrations22. We found only one time series analysis of air pollution and hospitalization south of the equator where winter, a time of enhanced respiratory viral transmission, occurs at a different time of the calendar year than north of the equator. In a municipality of Sao Paulo, Brazil, Santos et al. (2022) reported positive associations between hospitalizations and O3 lagged 2 days, and NO2 lagged 3 days23. No effect was found with PM10 and PM2.5 was not mentioned. The present study investigated the association between acute changes in the ambient air pollutant concentrations, PM2.5, NO2, O3, SO2, PM10 and carbon monoxide (CO), and COVID-19 related hospitalizations in Santiago, Chile between 16 March and 31 August 2020, during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study population

We included residents of the 32 comunas of the Province of Santiago, Chile and two adjacent urban comunas, Puente Alto, and San Bernardo. Figure 1, the regional map has been previously published20. The comunas were grouped into nine sectors, as following: Cerrillos, El Bosque, Independencia, La Florida, Las Condes, Parque O´Higgins, Pudahuel, Puente Alto, and Quilicura (Table 1).

Map of Santiago, Chile. The numbers represent the location of air pollution monitoring stations in each of the nine colour-coded sectors: (1) Las Condes, (2) Parque O´Higgins, (3) Cerrillos, (4) Pudahuel, (5) Independencia, (6) La Florida, (7) El Bosque, (8) Puente Alto, (9) Quilicura. (Souce: Santiago Province in Chile, Census Data, 2020). The map was created using: ArcGIS Desktop 10.6 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/resources).

Hospitalization data

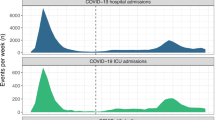

Daily hospital discharge data recorded between March 16th and August 31st, 2020 were obtained from the Chilean Statistical Institution and provided by the Ministry of Environment of Chile. The International Classification of Disease 10th Revision (ICD-10)24 codes a laboratory confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 as U07.1 and “a clinical or epidemiological diagnosis of COVID-19, where laboratory confirmation is inconclusive or not available” as U07.2. In the present study, either of the two codes was considered.

Air quality data

Each of the nine sectors (Fig. 1) has a stationary ground-based air quality monitor from which we obtained 24-h average concentrations for PM2.5, NO2, O3, PM10, SO2, and CO. For Cerrillos and Quilicura sectors, only PM2.5 measurements were available. SO2 was only available for three sectors. Twenty-four hour mean temperature and relative humidity were also collected from the ground-based monitors. Hospitalized cases were linked to ambient air pollution and weather variables by each sector of residence.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis has been previously described20. Daily variations in the number of COVID-19 related hospitalizations were related to daily variations in ambient air pollutants concentrations by a two-stage random-effects regression model for count data as described in Cakmak et al. (2007), which assumes a Poisson distribution19. A linear association between air pollution and hospitalization on the logarithmic scale was assumed, with the association varying at random between sectors19,25. In the first stage, sector-specific regression parameter estimates of the pollution–hospitalization association were obtained. In the second stage, these estimated sector-specific regression parameters were then pooled using random-effects models26. First, separate analyses were used for each sector. Unwanted temporal trends (e.g., epidemics from viral respiratory illnesses) in daily hospitalization were addressed by sector using natural nonparametric splines functions for day-of -study and testing knots for every 15, 30, 45, and 60 days of observation. Model selection was based on minimization of the Akaike information criterion (AIC), a measure of model prediction. Additionally, Bartlett’s test was used to demonstrate that the model residuals did not display any type of structure, including serial correlation. Having selected the optimal model for time, we then tested 24-h mean temperature and relative humidity on the day of hospitalization and up to 6 days before hospitalization, for inclusion in the model using stepwise backwards and forwards regressions, while keeping the variables for time and day-of-the-week constant. Potential nonlinear associations of weather with hospitalization were addressed using natural spline functions. We examined linear weather models and models with up to 4 knots. The model that minimized the AIC was selected as the optimal weather model for each sector separately. An indicator variable in the models represented day-of-the-week to account for any possible differences in hospitalization rates between days of the week. Finally, we tested the effect of air pollution on the day of admission and the previous six days exposure using unconstrained distributed lags as described by Schwartz (2000)27. In the second stage, the regression parameter estimates assessing the associations between pollution and COVID-19 hospitalization within each sector were pooled using a random effects model26. Factors, such as age, sex, social status, and population density, were not adjusted for because they were assumed to be time invariant over the relatively short duration of the study. Sector specific estimates were pooled using the random effects model to calculate the overall effect sizes to air pollution related COVID-19 hospitalizations. In addition, two-pollutant models, each of which included adjustment for one of co-pollutants, were fitted. The association of air pollutants concentrations with hospitalizations was considered robust if the effect estimates in the single-pollutant and two-pollutant models were not significantly different, as determined by non-overlapping confidence intervals which indicates the differences were not significant at p < 0.05. To assess the robustness of the results to the lag structure used, we calculated lag 0 (or same day exposure) effects. Results, overall and individual, were stratified by age and biological sex. Results were presented as the pooled percent change in COVID-19 hospitalization for an interquartile range (IQR), the 25th to the 75th percentiles, concentration of each ambient pollutant. This nonparametric statistic naturally excludes extreme values, which could skew the estimate of effect. The data were analysed using an R program version 4.0.228.

Results

26,579 COVID-19 related hospitalizations occurred between March and August 2020 of which 24,501 were laboratory confirmed, resulting in a daily average of 158 cases. The median age of participants was 62 years old and 59% were males. Mean air pollution concentrations (IQR) were 0.73 ppm (0.43) for CO, 19.89 ppb (9.69) for NO2, 14.21 ppb (9.42) for O3, 29.78 µg/m3 (18.39) for PM2.520, 69.44 µg/m (33.78) for PM10, and 9.02 ppb (3.35) for SO2 (Table 1). El Bosque had the highest recorded NO2 and PM10 levels, Cerrilos had the highest PM2.5. O3 was highest in Parque O’Higgins, and CO was highest in El Bosque and Pudahuel. The highest concentration of SO2, was recorded in La Florida (Table 1).

In the overall population of Santiago there were significantly increased risks (p < 0.05) of daily hospitalizations from COVID-19 for an IQR increase in CO, NO2, and PM2.5, of 1.1 (0.20, 2.0), 0.30 (0, 0.50), and 2.7 (1.9, 3.0), respectively, using distributive lags with cumulative percent changes in estimates (Table 2). The overall and sex-stratified effect sizes for O3 were not significant (p < 0.05) but subgroup analysis by age produced variable results with a significantly positive association for the youngest age group and a negative association among the 65–74 years old subgroup. The overall SO2 estimate of effect was not significant but there was a significant positive association for the > 84 years old age group and a significant negative association for the 65–74 year olds. Effect sizes for PM2.5, PM10, and SO2 were largest in the oldest age group. Compared to males, percent change in estimates for females were larger for CO, NO2, PM2.5, and PM10.

To test the sensitivity of the results to the lag structure used, we also calculated lag 0 (same day exposure) effects. Estimates were very similar to those using distributed lags with percent change in (95%CI) for CO, NO2, and PM2.5 of 1.09 (0.20, 1.96), 0.30 (0, 0.50), and 2.63 (1.86, 3.38), respectively.

We tested the sensitivity of findings to the presence of co-pollutants using two pollutant models, CO lost its significance at p < 0.05 (confidence interval included 0) when either NO2 or PM2.5 were added to the model (Table 3). NO2 became non-significant when either PM2.5, PM10 or SO2 were added to the model. The SO2 effect became significantly negative when either CO, NO2, PM2.5, PM10 were added to the model.

Discussion

We found that, in single pollutant models, overall hospitalizations from COVID-19 increased on days of higher concentrations of ambient CO, NO2, and PM2.5. The effect of PM2.5 was robust, persisting despite subgroup analyses and adjustment for co-pollutants. Its observed effect was significantly less, p < 0.05, for males than females, and for those < 65 years old compared to those who were older. The observed PM10 effect was consistently non-significant across subgroups and in two-pollutant models. Estimates for O3 were not significant overall, in two -pollutant models, or when stratified by sex, and variable findings were noted in age subgroup analysis with significantly negative, significantly positive and non-significant results. The absence of SO2 measures for the majority of sectors together with stratification significantly reduced the sample size available for analysis. Unlike the robust effects of PM2.5, SO2 effects were inconsistent, with stratification increasing the probability of chance associations which were in different directions by age group.

Ambient air pollutants enhance oxidative stress and inflammation29 and have been associated with cardiac and pulmonary morbidity and mortality30, including an increased risk of respiratory infection31. The adverse effects of PM2.5 may lower the threshold for a COVID-19 infected person to deteriorate and require hospitalization11. In addition, PM2.5 activates the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) receptor to which SARS-CoV-2 attaches to gain access to cells32. Another hypothesis explaining why there may be an association between exposure to PM2.5 and COVID-19 related hospitalization is that particulate air pollution may be a vector for microbial transmission33, including possibly the coronavirus34. The short lag time observed in the present study would support the former hypothesis that air pollution may contribute to the burden of illness in someone already ill with COVID-19.

Previous population-based studies indicate that air pollution in Santiago, Chile, is associated with increased morbidity and mortality19,20,35,36, but the influence of air pollution on COVID-19 related hospitalization has not been previously studied. An ecologic study of continental Chile compared urban PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations estimated for the year 2016 to COVID-19 incidence and mortality in 2020 between communas normalized by the population size determined by a 2017 census. Adjusted incidence but not mortality was associated with the two air pollutants37. Outside of Chile, there have been several studies comparing hospitalization rates between geographic areas with different levels of ambient air pollution9,10. However, study designs comparing different populations are susceptible to confounding by regional differences in factors, such as age38, prevalence of underlying population comorbidities, socioeconomics18,39, urbanization/crowding16, weather40,41, and effectiveness of public health infection control measures. Focusing on Santiago, one study reported regional socioeconomic differences in the burden of illness due to COVID-1942. Rather than comparing morbidity between different geographically separated populations, our time-series analysis design contrasted the number of hospitalizations between higher and lower air pollution days in the same population in the same geographic area, thereby controlling for personal and geographic characteristics.

There are a few studies of short-term temporal association between air pollution and COVID-19 related hospitalization. A daily time series study done between February 1 and December 31, 2020, using lags of one, two, three, and four weeks found that NO2 was positively associated with daily COVID-19 related hospitalizations in six of eight Spanish regions, and PM10 and O3 in three regions21. Compared to Madrid, NO2 concentrations in Santiago were approximately double, 20.8 μg/m3 versus approximately 20 ppb (37.6 μg/m3), and the relative risks (RR) of hospitalization in our study was less than in Madrid 1.003 (95% CI 1.000, 1.005) per IQR (9.69 ppb) increase versus 1.007 (95% CI 1.006, 1.009) per 1 μg/m3 increase. Another population-based study conducted in the same year as our study, using simple correlation coefficients without comprehensively controlling for unwanted temporal variation, found that a five-day moving average of daily mean PM2.5 lagged by 20 days was positively associated with admissions to critical care in Florence, Italy (median PM2.5 11.4 ug/m3) and Milan (median PM2.5 17.8 μg/m3), but not in the Trento province17. NO2 was also positively associated with admissions in Trento province (median 18.3 ppb) and Florence (median 65 ppb) but not in Milan17. Diaz et al. (2021) reported that hospitalizations in 2020 in Madrid were higher on days of higher NO2 concentrations with a RR of 1.12 (95% CI 1.01, 1.24) per 10 μg/m3 increase, but not on days of higher PM10 concentrations22. If values were averaged over 14 days, hospitalizations were associated with PM10 with RR of 1.56 (95% CI 1.06, 2.20) per 10 μg/m3 increase, but not with NO2. The RR of hospitalization associated with NO2 were greater in Madrid than in Santiago highlighting the difficulty of trying to interpret associations between air pollution and COVID-19 hospitalizations based on comparisons between different geographic areas. Santos et al. (2022) using a time-series design, reported a relative risk of hospitalization to be 1.061 (95% CI 1.016–1.108) for O3 and 1.125 (95% CI 1.050–1.205) for NO2 in a municipality of Sao Paulo, Brazil23. There was no significant effect of PM10, and PM2.5 was not measured. We also found a positive effect of NO2 exposure and no significant effect of PM10. The largest effect size in our study was for PM2.5.

Strengths and Limitations: Our study has several relatively unique features. Previously, there have been very few time-series population-based studies of pollution-related COVID-19 hospitalization, and no studies were done in Santiago, Chile. Unlike other similar studies, we demonstrated the robustness of PM2.5 pollutant using two-pollutant models. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an association between COVID-19 related hospital admissions and the three ambient pollutants, CO, NO2, and PM2.5 using time series analysis to study short-term effects controlling for unwanted temporal variation. It is also one of the few such studies done in the southern hemisphere where the early pandemic occurred during the autumn rather than the early spring in the Northern hemispheres. The daily high and low temperatures in July are approximately 16 °C and 3 °C in Santiago, Chile. Winter weather with less sunlight, drier air, and lower temperatures may enhance virus survival43, and thus, modify the risk of COVID-19 related morbidity.

Being an observational study, the observed associations, in isolation, cannot be considered causal. However, the argument for causality is strengthened by previous publications of increased overall and COVID-19 related mortality on higher air pollution days in Santiago19,20, and the evidence for a plausible mechanism to explain the association32. The measurement error created by attempting to reflect personal exposure to air pollutants based on ambient stationary monitors is likely random and would tend to bias findings towards the null. This would suggest that the observed effect sizes are likely underestimated44. For our time series analysis we assumed that on average personal exposure is higher on days of higher ambient air pollution than on days of lower ambient air pollution and a previous study demonstrated positive correlations between ambient and personal exposure in Santiago45.

Conclusion

Our study provides evidence of a significant association between short-term increases in ambient PM2.5, CO, and NO2 levels and daily COVID-19 related hospitalizations, with the most robust positive findings observed for PM2.5. These findings could help contribute to the overall body of evidence on air pollution and COVID-19 related illness and fill in knowledge gaps surrounding the short-term effects of ambient air pollution in an region south of the equator using a time series study design, which is relatively resistant to confounding by population-based characteristics. Furthermore, it could inform public health messaging and other efforts aimed at reducing air pollution, and possibly contribute to a reduction in the large burden of hospitalization from this novel coronavirus.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NO2 :

-

Nitrogen dioxide

- O3 :

-

Ozone

- PM2.5 :

-

Particulate matter of diameter ≤ 2.5 microns

- PM10 :

-

Particulate matter of diameter ≤ 10 microns

- RR:

-

Relative risks

- SO2 :

-

Sulfur dioxide

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID_19) pandemic. Available from https://covid19.who.int/, Accessed July 2023 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). COVID Data Tracker. Available from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#hospitalizations-landing, Accessed on July 2023 (2023).

Carrillo-Vega, M. F. et al. Early estimation of the risk factors for hospitalization and mortality by COVID-19 in Mexico. PLoS One 15(9), e0238905. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238905/ (2020).

Petrilli, C. M. et al. Factors associated with hospital admissions and critical illness among 5,279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 369, m1996 (2020).

Reilev, M. et al. Characteristics and predictors of hospitalization and death in the first 11: 122 cases with positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in Denmark: A nationwide cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49(5), 1468–1481 (2020).

Vahey, G. M. et al. Risk factors for hospitalization among persons with COVID-19-Colorado. PloS One 16(9), e0256917. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256917/ (2021).

Nyberg, T. et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (C.1.617.2) variants in England: A cohort study. Lancet 399(10332), P1303-1312 (2022).

Fattorini, D. & Regoli, F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the COVID-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 264, 114732 (2020).

Hernandez Carballo, I., Bakola, M. & Stuckler, D. The impact of air pollution on COVID-19 incidence, severity, and mortality: A systematic review of studies in Europe and North America. Environ. Res. 215(pt 1), 114155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022 (2022).

Marques, M. & Domingo, J. L. Positive association between outdoor air pollution and the incidence and severity of COVID-19. A review of the recent scientific evidences. Environ. Res. 203, 111930 (2022).

Bowe, B. et al. Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and the risk of hospitalization among COVID-19 positive individuals: Cohort study. Env. Int. 154, 106564 (2021).

Mendy, A. et al. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and hospitalization in COVID-19 patients. Respir. Med. 178, 106313 (2021).

Cole, M. A., Ozgen, C. & Strobl, E. Air pollution exposure and COVID-19 in Dutch municipalities. Environ. Resour. Econ (Dordr) 76(4), 581–610 (2020).

Bowe, B. et al. Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and the risk of hospitalization among COVID-19 positive individuals: Cohort study. Environ. Int. 154, 106564 (2021).

Charlton, L., Gale, C., & Morgan J. Long-term outdoor air pollution and COVD-19 mortalities in London: An individual-level analysis (preprint). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.16.23286017.

Copiello, S. & Grillenzoni, C. The spread of 2019-nCoV in China was primarily driven by population density. Comment on “Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 infection: Evidence from China” by Zhu et al. Sci. Total Environ. 744, 141028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141028 (2020).

Lolli, S. et al. Impact of meteorological conditions and air pollution on COVID-19 pandemic transmission in Italy. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16213. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73197-8 (2020).

Anderson, G. et al. Using socioeconomics to counter health disparities arising from the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 369, m2149 (2020).

Cakmak, S., Dales, R. E. & Vidal, C. B. Air pollution and mortality in Chile: Susceptibility among the elderly. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 524–527. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.9567 (2007).

Dales, R. et al. The association between air pollution and COVID-19 related mortality in Santiago, Chile: A daily time series analysis. Environ. Res. 198, 111284 (2021).

Linares, C. et al. Impact of environmental factors and Sahara dust intrusions on incidence and severity of COVID-19 disease in Spain. Effect in the first and second pandemic waves. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 28(37), 51948–51960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14228-3 (2021).

Diaz, J. et al. Does exposure to noise pollution influence the incidence and severity of COVID-19?. Environ. Res. 195, 110766 (2021).

Santos, A. O. R. et al. Exposure to air pollution and hospitalization due to COVID-19 in Sao Jose dos Campos. Brazil. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 55, e12273 (2022).

World Health Organization (WHO). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. Available from https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en. Accessed June, 2023 (2019).

Bell, M. L., Dominici, F. & Samet, J. M. A meta-analysis of time-series studies of ozone and mortality with comparison to the National Morbidity, Mortality, and Air Pollution Study. Epidemiology 16, 435–445 (2005).

DerSimonian, R. & Nan, L. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controll. Clin. Trials 7(3), 177–88 (1986).

Schwartz, J. The distributed lag between air pollution and daily deaths. Epidemiology 11(3), 320–326 (2000).

R version 4.0.2 (2020–06–22) -- "Taking Off Again". Copyright (C) 2020 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Platform: x86_64-w64-mingw32/x64 (64-bit).

Tsai, D.-H. et al. Effects of short- and long-term exposures to particulate matter on inflammatory marker levels in the general population. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 19697–19704 (2019).

World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Health aspects of air pollution: results from the WHO project “Systematic review of health aspects of air pollution in Europe”. Copenhagen WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107571. Accessed on July 2023 (2004).

Ciencewicki, J. & Jaspers, I. Air pollution and respiratory viral infection. Inhal Toxicol. 19(14), 1135–1146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958370701665434 (2007).

Comunian, S. et al. Air pollution and COVID-19: The role of particulate matter in the spread and increase of COVID-19’s morbidity and mortality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(12), 4487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124487 (2020).

Cao, C. et al. Inhalable microorganisms in Beijing’s PM2.5 and PM10 pollutants during a severe smog event. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48(3), 1499–507. https://doi.org/10.1021/es4048472 (2014).

Nor, N. S. M. et al. Particulate matter (PM2.5) as a potential SARS-CoV-2 carrier. Sci. Rep. 11, 2508. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81935-9) (2021).

Ostro, B. et al. Air pollution and mortality: Results from a study of Santiago. Chile. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 6, 97–114 (1996).

Cifuentes, L. A. et al. Effect of the fine fraction of particulate matter versus the coarse mass and other pollutants on daily mortality in Santiago. Chile. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 50, 1287–1298 (2000).

Salgado, V. et al. Long-term exposure to fine and coarse particulate matter and COVID-19 incidence and mortality rate in Chile during 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(14), 7409 (2021).

Lopez-Gay, A. et al. Sociodemographic determinants of intraurban variations in COVID-19 incidence: The case of Barcelona. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 76, 1–7 (2022).

Mari-Dellolmo, M. et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in COVID-19 in a European urban area: Two waves, two patterns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(3), 1256 (2021).

Adhikari, A. & Yin, J. Short-term effects of ambient ozone, PM2.5, and meteorological factors on COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths in queens, New York. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(11), 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114047 (2020).

Ganslmeier, M., Furceri, D. & Ostry, J. D. The impact of weather on COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 11, 222027 (2021).

Mena, G. E. et al. Socioeconomic status determines COVID-19 incidence and related mortality in Santiago, Chile. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg5298 (2021).

Ahlawat, A. et al. Preventing airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals and nursing homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(22), 8553 (2020).

Zeger, S. L. et al. Exposure measurement error in time series studies of air pollution: Concepts and consequences. Environ. Health Perspect. 108, 419–426 (2000).

Rojas-Bracho, L. et al. Measurements of childrens exposure to particles and nitrogen dioxide in Santiago. Chile. Sci. Total Environ. 287, 249–264 (2002).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C., A.L., and R.D. contributed to study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version of the article to be published. CBV and RM contributed data and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dales, R., Lukina, A.O., Romero-Meza, R. et al. Ambient air pollution exposure and COVID-19 related hospitalizations in Santiago, Chile. Sci Rep 14, 14186 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64668-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64668-3

- Springer Nature Limited