Abstract

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) is an emerging tick-borne virus with a mortality rate of up to 30%. First identified in China in 2009, it was later reported in other Asian countries, including Thailand in 2020. SFTSV has been detected in several tick species, including Rhipicephalus sanguineus, known for infesting dogs. We conducted a seroprevalence study of SFTSV in Bangkok and Nong Khai, Thailand, by analyzing 1162 human samples collected between 2019 and 2023. The testing method relied on IgG detection using ELISA and confirmed though a virus seroneutralization test. The results indicated that out of the participants, 12 (1.1%) tested positive for anti-SFTSV IgG antibodies; however, none exhibited positive results in the seroneutralization assay. Additionally, molecular detection of SFTSV, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Coxiella spp., Bartonella spp., and Rickettsia spp. was performed on 433 Rh. sanguineus ticks collected from 49 dogs in 2023 in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand. No evidence of these pathogens was found in ticks. These findings highlight the importance of exploring viral cross-reactivity. Furthermore, it is important to conduct additional studies to isolate SFTSV from animals and ticks in order to identify the potential transmission routes contributing to human and animal infections in Thailand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), is an emerging tickborne disease caused by the severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), also known as Dabie bandavirus (Phenuiviridae family, Bandavirus genus)1,2,3. SFTSV has been detected in a range of animal species including sheep, cattle, dogs, cats, deer, wild boards, raccoons, rodents, and hedgehogs4. Humans are incidental hosts who contract the virus through bites from SFTSV-carrying ticks, by direct contact with body fluids of infected patients or infected pets2,5. Clinical manifestations are broad and include fever, leukopenia (< 4000/mm3), thrombocytopenia (< 100,000/mm3), gastrointestinal symptoms, neurological symptoms, and multiple organ failure3,6, with a case-fatality rate ranging from 6 to 30%3.

Haemaphysalis longicornis commonly known as the Asian longhorned tick, acts as the primary transmission vector and reservoir, and is endemic in the Asia–Pacific region2,3. However, SFTSV has also been detected in several other tick species, including Amblyomma testudinarium, Ixodes nipponensis, and Rhipicephalus microplus7. Another tick species, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae), commonly referred to as the “brown dog tick”8,9 has also been demonstrated to play a potential vector role in SFTSV transmission10. It is the most common tick species that parasitizes dogs in both rural and urban areas worldwide, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions where its prevalence persists throughout the year. Occasionally, it infects humans, often associated with heavily infected dogs and highly infested environments11.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus was first reported in humans in China in 2009, in rural areas of the Hubei and Henan provinces. It subsequently spread to other provinces, leading to outbreaks with thousands of cases. Later, SFTSV was identified in other Asian countries, including the Republic of Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Myanmar, Taiwan, and Thailand5,12. In Thailand, the virus was initially reported in 2020 and, as of January 2024, four cases have been identified. The first case was a 70-year-old woman with suspected transmission through cats13, and the remaining cases were identified in a retrospective study conducted among patients hospitalized in or near Bangkok between 2019 and 202014.

Seroprevalence studies in humans have been conducted in China, Japan, Korea3, Pakistan15, and Vietnam16. In Thailand, seroprevalence studies in humans have not been performed, but a seroprevalence study in dogs was conducted in 2022, which demonstrated the presence of antibodies. In addition, the virus was also isolated from a dog4.

In the present study, we conducted the first human seroprevalence study in Thailand by analyzing serum samples from healthy individuals in Bangkok and from patients with dengue-like symptoms collected in Nong Khai Province to provide information on the circulation of SFTSV in the country. Furthermore, we performed molecular detection assays to detect SFTSV and other pathogens, including Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Coxiella spp., Bartonella spp., and Rickettsia spp. in Rh. sanguineus ticks collected from dogs residing in rural communities of Tha Takiap Subdistrict, Chachoengsao Province, Thailand, to identify potential pathogen transmission by this tick.

Materials and methods

Human sample collection and ethical approval

One milliliter of residual serum samples was collected from 940 asymptomatic adult volunteer blood donors who attended the National Blood Centre of the Thai Red Cross in Bangkok in November 2023. Additionally, 222 leftover samples were obtained from individuals suspected of dengue virus (DENV) infection at Phonphisai hospital in Phonphisai district, Nong Khai Province, Thailand, between 2019 and 2020 (Fig. 1). Bangkok is the capital and most populous city of Thailand, with an estimated population of more than 11 million people as of 202417. Phonphisai district is a rural area in the upper northeastern region of Thailand, with an estimated population of 71,864 people in 202418.

Geographical distribution map of sample collection sites. In yellow: human samples. In green: Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks collected from dogs. The map was created using Mapchart (https://www.mapchart.net/).

Serum samples were sent to the Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, in cold chain and were stored at − 20 °C prior to serological analyses. An anonymous data collection form was filled out by the National Blood Centre and included data on age, sex, province, district, and occupation. Data on age and sex were also gathered from individuals presenting dengue-like symptoms.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (COA No. MU-CIRB 2023/167.2505), the National Blood Center Thai Red Cross Society (COA No. NBC 15/2023), and Ethical Review Committee for Human Research Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University (Protocol No. 88/2564). Written informed consent was obtained from adult participants, or parent/legal guardian in individuals under the age of 18 years, prior to enrolment.

Human serological testing

A two-step method was used to detect IgG antibodies against SFTSV. First, serum samples were screened using a commercial anti-SFTSV IgG ELISA kit (Zhongshan Bio-tech Co., Ltd. Guangdong, China), based on the viral nucleoprotein, and performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction19. ELISA IgG was considered positive when the sample optical density (OD) was greater than or equal to the cutoff value (the average of OD value of negative control + 0.10). This commercial kit has been employed in other studies19,20,21,22, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting SFTSV antibodies. Second, an in-house virus neutralization test (VNT) was performed for all samples with a positive ELISA result to detect SFTSV-specific neutralizing antibodies. One hundred TCID50 (tissue culture infectious dose) of the SFTSV SPL010A strain (provided by European Virus Archive Global (EVAg)) was mixed with equal volume of serially diluted serum (1:10 to 1:320) and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 1 h. Subsequently, the mixture was transferred onto 96 well plate containing confluent Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 1 h. Following incubation, serum + virus mix was removed, and cell monolayers were washed twice with Minimum Essential Medium (MEM). Finally, 200 µl of MEM/2,5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was transferred on each well, and plates were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. As the SPL010A strain does not exhibit distinct cytopathic effect (CPE) on Vero cells, the endpoint assessment was conducted by quantifying the quantity of RNA copy numbers using qRT-PCR (Supplementary Table S1). At the end of the of the incubation; RNA was extracted from cell culture supernatants, and qRT-PCR was performed using sensitive and specific primers and probe (Supplementary Table S2) (These primers detect both Chinese and Japanese SFTSV and are capable of detecting viral RNA up to 1 TCDI50/reaction, as described23). The percentage reductions of viral copy number for each serum dilution were computed relative to the virus control, which included only the virus. Titer values were presented as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that reduced the RNA copy number in the virus control by at least 75%. A constructed control plasmid and a standard IVT-RNA with a known concentration (Supplementary Table S1) were used for qRT-PCR and VNT, respectively.

A sample was considered positive for SFTSV IgG antibodies when both, ELISA IgG and VNT were positive. For VNT tests, all experiments were performed in biosafety level 3 laboratory (BSL3) at the Unité des Virus Émergents, Marseille, France, according to standard BSL3 guidelines. All dilutions and liquid transfers were performed using an automated system (Epmotion 5075). Reactions were performed using Invitrogen SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) in a CFX96 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, California, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Tick sample collection and ethical approval

In October, 2023, ticks were handpicked from 49 dogs in rural communities of Tha Takiap Subdistrict, Chachoengsao Province, Thailand, situated in the eastern part of the country (13° 22′ 53.3″ N 101° 42′ 04.0″ E) (Fig. 1), which had a population of 19,412 people by 202224. The Tha Takiap Subdistrict is characterized by its hilly slopes, mountain ranges, and relatively intact rainforests. During the collection process, all dogs were captured and examined for ticks with the assistance of their owners. Ten ticks were randomly collected from each dog, in cases with fewer ticks, all available ticks were collected. After collection, the live tick samples were sent to the laboratory at the College of Allied Health Sciences, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University’s Samut Songkhram Campus. The non-engorged ticks were euthanized by freezing at − 20 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, all ticks were washed in sterile physiological saline and preserved in RNAlater, stored in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes at − 20 °C. Morphological identification of the ticks was performed using a taxonomic key25 under a Nikon SMZ 800 N stereo-microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Engorged female ticks were kept at room temperature for a week to encourage oviposition. After oviposition, these female ticks and their eggs were preserved and stored in microcentrifuge tubes at − 80 °C. The ticks were then grouped based on developmental stage (adult, nymph), sex (male, female), and the host animal from which they were collected. These categorized and labeled tubes were transported to the Faculty of Medical Technology at Mahidol University in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, and stored at − 80 °C for further analysis.

The experimental protocol and tick sample collection were duly submitted for review and subsequently received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University (No. IACUC 66–002/2023).

DNA and RNA extraction

Microcentrifuge tubes containing pooled ticks were immersed in liquid nitrogen and crushed using a sterilized plastic pestle. After homogenization, the preparations were resuspended in 400–600 μl of sterile 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at − 80 °C. Prior to extraction, the homogenates were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were used to extract the total DNA/RNA using Nucleospin RNA virus extract kit (Macherey–Nagel, Germany), adding Proteinase K, following the manufacturer’s instructions, with a final elution volume of 80 μl. Extractions were subsequently stored at − 80 °C for further molecular analyses.

PCR analyses

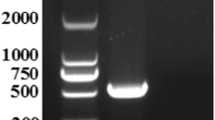

Taq-Man real-time polymerase chain reactions (qPCR or RT-qPCR) were employed to amplify pathogens, including SFTSV23, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF)26, Coxiella spp.27, Bartonella spp.28, and Rickettsia spp.29. Primers and probes (Supplementary Table S2), as well as bacteriophages MS2 and T4 (used as internal controls30), were provided in a lyophilized format31. Constructed plasmids were used as positive controls. All were kindly supplied by the European Virus Archive global (EVAg) and the Emerging Viruses Unit in Marseille, France. Reactions were performed using Invitrogen SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) in a CFX96 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, California, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysis

For the expected prevalence of 3.0% based on similar studies conducted in other countries, the required sample size was 1165 for the margin of error or absolute precision of ± 1 in estimating the prevalence with 95% confidence and considering the potential loss of 4.0%. With this sample size, the anticipated 95% confidence interval (CI) was 2.0–4.0%. The sample size was calculated using the Scalex SP calculator32.

Results and discussion

The four human cases reported in Thailand identified in Bangkok and Chachoengsao Province between 2019 and 2020, indicate that SFTSV has been spreading in the country. Therefore, we examined the seroprevalence of anti-SFTSV IgG antibodies in 1162 human samples collected from 940 healthy blood donors in Bangkok with a median age of 41 years (range 17–68 years) and from 222 individuals with dengue-like symptoms in Nong Khai Province, with a median age of 15 years (range 8 months–67 years). The results of the initial ELISA screening for anti-SFTSV IgG antibodies revealed that 12 (1.1%) human samples were positive, with 5 from blood donors (3 company employees and 2 civil servants) and 7 from patients, with ELISA optical density ranging from 0.14 to 0.72 (mean OD = 0.26). The median age of the positive individuals was 40 years (range 16–57 years), with a prevalence of males 10/12 (83.3%). After confirmation by VNT, none of the samples tested positive, indicating the absence of neutralizing antibodies (Table 1).

Seroprevalence studies have also been performed in other countries, including China (0.2–11.3%)33,34, Japan (0.0–4.2%)34,35,36,37,38,39, South Korea (1.9–7.7%)40,41,42,43,44, Pakistan (2.5%)15, and Vietnam (3.6%)16. The detection methods used were predominantly ELISA tests. Given that the seroprevalence rate in this current study was determined to be 1.1% using ELISA, this figure aligns with some studies from China, Japan, and South Korea. Further studies must be conducted to determine whether any viruses antigenically related to SFTSV are present in Thailand. For instance, Guertu virus (GTV), which was recently isolated from D. nuttalli ticks in China, is closely related to SFTSV and can also infect humans45.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in domesticated animals has recently gained public attention for its potential role as an infection source to humans. For instance, the first human case of SFTS in Thailand was a 70-year old woman suspected of having been infected by cats, as all seven of her cats died13. In Thailand, the presence of stray or neglected companion dogs, and the widespread popularity of dog ownership, pose an important source of infection46, as clinical signs of SFTSV-infected dogs are relatively mild, making the diagnosis difficult and barely attracting enough attention to their owners and veterinary professionals37. Moreover, a SFTSV seroprevalence study published in 2023 and conducted in dogs, demonstrated a total seroprevalence of 16.6% (ELISA and seroneutralization) in the provinces of Bangkok, Chachoengsao, Samut Prakan, Rayong, and Chonburi, suggesting that infection among the canine population may be similar to those in endemic regions of China4.

Rh. sanguineus tick infestation in dogs in Thailand is high (e.g. north-eastern 80.0%), which represents public health significance due to its greater likelihood of spreading pathogens. Since it requires different hosts for each blood meal, and in the era of globalization and climate changes, it has been suggested that ticks exposed to high temperatures attached more to humans, potentially increasing the risk of transmission of certain zoonotic pathogens11. Therefore, we collected 433 Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato ticks from dogs in rural communities of Chachoengsao Province, Thailand, where one human case of SFTSV was identified in 202014, and a seroprevalence of 11.1% was found in dogs in 2022 (confirmed by FRNT50)4. Two hundred fifty-three (58.4%) ticks were male, 55 (12.7%) were females and 125 (28.9%) engorged female ticks. Almost all were adults, except for four nymphs. In addition, 12 tubes of eggs were collected. All pool of ticks and eggs were tested for the detection of SFTSV (Table 1). However, none of the pools were positive for RNA detection. As Haemaphysalis longicornis serves as the primary vector, and considering that livestock are common hosts for this tick47, we also investigated the presence of ticks on 10 cattle and 15 goats in the same area of study. These animals are raised in the same household as dogs. However, no ticks were found on the livestock, probably due to the use of insecticides, since these animals are raised for sale.

Rh. sanguineus ticks have been identified as responsible for transmitting various well-known canine pathogens, including Babesia vogeli, Babesia canis, Hepatozoon canis, and Mycoplasma haemocanis, as well as pathogens capable of infecting both humans and dogs, such as Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys, and several zoonotic Rickettsioses11,48,49. In this study, we tested less common but important pathogens that cause important health problems in humans, mainly transmitted by other tick species, but also found in Rh. sanguineus ticks, including CCHF, Coxiella spp., Bartonella spp., and Rickettsia spp. However, we did not detect RNA or DNA from the collected tick samples.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the seroprevalence study involved a disproportionately higher number of samples from urban areas compared to rural ones, with only a few samples from farmers. The sample size did not reflect the entire country’s population. Additionally, the study did not consider the influence of socioeconomic factors, outdoor activities, or history of tick-bites. Secondly, molecular identification was performed on a single tick and animal species and was confined to a specific area, potentially masking positive results. However, our study also has several strengths. Notably, this is the first seroprevalence study conducted on human samples in Thailand. The sample sizes are comparable to those of other countries and are appropriate for our study based on statistical formulas. Serum samples were collected in Bangkok, where most of the positive cases were identified. Collection from blood donors represents the healthy population and facilitates large-scale and cost-effective seroprevalence studies, allowing longitudinal trend analysis. In addition, serum samples were collected from a rural area bordering Laos, where the population may be more susceptible to tick-borne infections. The combination of ELISA and seroneutralization tests used in this study provides greater specificity, outperforming methodologies based solely on ELISA. Molecular identification of SFTSV in Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks collected from dogs is significant due to the high infestation and the presence of human and dog infections found in the same province where the ticks were collected, potentially representing a source of infection. Although, no positive results were detected, this information is crucial for identifying potential increases in incidence or geographic range in the future. To achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the virus and the associated disease, it is important to conduct further studies across diverse geographic regions and on various tick species, including Haemaphysalis longicornis.

Conclusion

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus poses an escalating global public health threat not only due to the segmented nature of its viral genome, which promotes frequent reassortment events, but also because of its increasing incidence, expanding geographical distribution, and high mortality rates. Individuals engaged in agriculture and forestry are considered at heightened risk of tick-borne infections. Moreover, close contact with domestic animals is also thought to be a significant risk factor for SFTSV transmission. To our knowledge, this is the first study of SFTSV seroprevalence in humans in Thailand. We demonstrate the current absence of neutralizing antibodies against SFTSV in the samples collected from Bangkok and Phon Phisai district (Nong Khai province). Additionally, we observed a considerable infestation of the tick species Rhipicephalus sanguineus in dogs in Chachoengsao, Thailand. Nonetheless, the presence of RNA or DNA of SFTSV, CCHF, Coxiella spp. Bartonella spp., and Rickettsia spp. was not detected. Our findings highlight the importance of performing sustained surveillance to promptly detect emerging diseases in animals, vectors, and humans to better respond to health threats.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the study are available within the article. Additional data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Sharma, D. & Kamthania, M. A new emerging pandemic of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS). VirusDisease 32, 220 (2021).

Casel, M. A., Park, S. J. & Choi, Y. K. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus: Emerging novel phlebovirus and their control strategy. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 713–722 (2021).

Seo, J.-W., Kim, D., Yun, N. & Kim, D.-M. Clinical update of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Viruses 13, 1213 (2021).

Ishijima, K. et al. High seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection among the dog population in Thailand. Viruses 15, 2403 (2023).

Yang, T., Huang, H., Jiang, L. & Li, J. Overview of the immunological mechanism underlying severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 50, 118 (2022).

Sul, H. et al. Development of a scoring system to differentiate severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome from scrub typhus. Viruses 14, 1093 (2022).

Han, X.-H. et al. Identification of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus genotypes in patients and ticks in Liaoning Province, China. Parasites Vectors 15, 120 (2022).

Xing, Y. et al. Epidemiological investigation of predominance tick and the infectious status of severe fever thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Penglai and Laizhou counties, Shandong province. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 49, 993–997 (2015).

Hu, Y.-Y. et al. Role of three tick species in the maintenance and transmission of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008368 (2020).

Yuan, C. et al. Infection and transovarial transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Rhipicephalus sanguineus in Hainan Island, China. Integr. Zool. 18, 1009–1013 (2023).

Dantas-Torres, F. Biology and ecology of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Parasites & Vectors 3, 26 (2010).

Yu, X.-J. et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med 364, 1523–1532 (2011).

Ongkittikul, S., Watanawong, R. & Rompho, P. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus: The first case report in Thailand. Bangkok Med. J. 16, 204–204 (2020).

Rattanakomol, P. et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection, Thailand, 2019–2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 28, 2572–2574 (2022).

Zohaib, A. et al. Serologic evidence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and related viruses in Pakistan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. CDC https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.190611 (2020).

Tran, X. C. et al. Serological evidence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and IgM positivity were identified in healthy residents in Vietnam. Viruses 14, 2280 (2022).

Bangkok Population 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/bangkok-population.

3 หมอรู้จักคุณ :: กรมสนับสนุนบริการสุขภาพ. https://3doctor.hss.moph.go.th/main/rp_tambon?region=8&prov=NDM=&provn=4Lir4LiZ4Lit4LiH4LiE4Liy4Lii&id=4305&n=4LmC4Lie4LiZ4Lie4Li04Liq4Lix4Lii.

Huang, X. et al. Estimation of the incidence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in high endemic areas in China: An inpatient-based retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 66 (2018).

Direct transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from farm-raised fur animals to workers in Weihai, China | Virology Journal | Full Text. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-024-02387-x.

Liang, S., Li, Z., Zhang, N., Wang, X. & Hu, J. Detection of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus RNA and total antibodies in wild animals, Jiangsu, China, 2014–2019. J. Public Health Emerg. 6, (2022).

Quan, C. et al. SFTSV infection is associated with transient overproliferation of monoclonal lambda-type plasma cells. iScience 26, 106799 (2023).

Yoshikawa, T. et al. Sensitive and specific PCR systems for detection of both Chinese and Japanese severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus strains and prediction of patient survival based on viral load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 3325–3333 (2014).

องค์การบริหารส่วนตำบลท่าตะเกียบ. https://www.thatakieb.go.th/event.php.

Farid, H. A. Morphological keys for the separation of the Rhipicephalus sanguineus group of ticks (Acarina:Ixodidae) in Egypt. J. Egypt Soc. Parasitol. 26, 453–460 (1996).

Wölfel, R. et al. Virus detection and monitoring of viral load in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1097–1100 (2007).

Mediannikov, O. et al. Coxiella burnetii in humans and ticks in rural Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4, e654 (2010).

Socolovschi, C., Kernif, T., Raoult, D. & Parola, P. Borrelia, Rickettsia, and Ehrlichia species in bat ticks, France, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 1966–1975 (2012).

Wright, C. L. et al. Rickettsia parkeri in gulf coast ticks, southeastern Virginia, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 896–898 (2011).

Ninove, L. et al. RNA and DNA bacteriophages as molecular diagnosis controls in clinical virology: A comprehensive study of more than 45,000 routine PCR tests. PLoS One 6, e16142 (2011).

Thirion, L. et al. Lyophilized matrix containing ready-to-use primers and probe solution for standardization of real-time PCR and RT-qPCR diagnostics in virology. Viruses 12, 159 (2020).

Naing, L., Nordin, R. B., Abdul Rahman, H. & Naing, Y. T. Sample size calculation for prevalence studies using Scalex and ScalaR calculators. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 22, 209 (2022).

Li, P. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 12, e0175592 (2017).

Huang, X. Y. et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of transmission mode. Epidemiol. Infect. 148, e239 (2020).

Kimura, T. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) virus antibodies in humans and animals in Ehime prefecture, Japan, an endemic region of SFTS. J. Infect. Chemother. 24, 802–806 (2018).

Gokuden, M. et al. Low seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus antibodies in individuals living in an endemic area in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 71, 225–228 (2018).

Kirino, Y. et al. Retrospective study on the possibility of an SFTS outbreak associated with undiagnosed febrile illness in veterinary professionals and a family with sick dogs in 2003. J. Infect. Chemother. 28, 753–756 (2022).

Ando, T. et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in cats and its prevalence among veterinarian staff members in Nagasaki, Japan. Viruses 13, 1142 (2021).

Matsumoto, C. et al. Investigation of antibody to severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) in blood samples donated in a SFTS-endemic area in Japan. Vox Sang. 113, 297–299 (2018).

Han, M. A. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus antibodies in rural areas, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 872–874 (2018).

Kim, C.-M. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome using specimens from the Korea National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011097 (2023).

Kim-Jeon, M. D. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Mui Island, Rural Area, Incheon, South Korea. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 52, 64–71 (2022).

Yoo, J. R. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in the agricultural population of Jeju Island, Korea, 2015–2017. Infect. Chemother. 51, 337–344 (2019).

Kim, K.-H., Ko, M. K., Kim, N., Kim, H. H. & Yi, J. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Southeastern Korea, 2015. J. Korean Med. Sci. 32, 29–32 (2017).

Shen, S. et al. A novel tick-borne phlebovirus, closely related to severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and Heartland virus, is a potential pathogen. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7, 95 (2018).

Colella, V. et al. Zoonotic vectorborne pathogens and ectoparasites of dogs and cats in Eastern and Southeast Asia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. CDC https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2606.191832 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Rapid spread of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus by parthenogenetic Asian longhorned ticks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. CDC https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2802.211532 (2022).

Do, T. et al. Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens in stray dogs and Rhipicephalussanguineus sensu lato ticks from Bangkok, Thailand. Pathogens 10, 561 (2021).

Galay, R. L. et al. Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens in canine population and Rhipicephalus sanguineus (sensu lato) ticks from southern Metro Manila and Laguna, Philippines. Parasit Vectors 11, 643 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pierre Combe and Grégory Mollé from the Unité des Virus Émergents, Marseille, France, and Kristy Ke from DAAN GENE for their collaboration with the diagnostic methods. We also would like to thank Miss Apiwan Pipatwanichkul from The Thai Red Cross Society and Mr. Chansak Wichit for their assistance with sample collection.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (OPS MHESI), Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) (Grant No. RGNS 64-172) and international postdoctoral fellowship 2022 provided by Mahidol University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.M.S.V., T.C., D.M, S.W., designed and supervised the study. T.C., S.L., T.P. collected the samples. P.M.S.V., E.N., C.B., L.T., developed the diagnostic methods. P.M.S.V, E.N., T.S., D.S. carried out the experiments. P.M.S.V. wrote the manuscript. T.C., E.F. X.D.L, T.C., S.W., D.M. edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saba Villarroel, P.M., Chaiphongpachara, T., Nurtop, E. et al. Seroprevalence study in humans and molecular detection in Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Thailand. Sci Rep 14, 13397 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64242-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64242-x

- Springer Nature Limited