Abstract

Pain, a widespread challenge affecting daily life, is closely linked with psychological and social factors. While pain clearly influences daily function in those affected, the complete extent of its impact is not fully understood. Given the close connection between pain and psychosocial factors, a deeper exploration of these aspects is needed. In this study, we aim to examine the associations between psychosocial factors, pain intensity, and pain-related disability among patients with chronic pain. We used data on 4285 patients from the Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry, and investigated pain-related disability, pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, psychological distress, perceived injustice, insomnia, fatigue, and self-efficacy. We found significant associations between all psychosocial variables and pain-related disability, even after adjusting for demographic factors. In the multiple regression model, sleep problems and pain intensity were identified as primary contributors, alongside psychological distress, and fatigue. Combined, these factors accounted for 26.5% of the variability in pain-related disability, with insomnia and pain intensity exhibiting the strongest associations. While the direction of causation remains unclear, our findings emphasize the potential of interventions aimed at targeting psychosocial factors. Considering the strong link between psychosocial factors and pain-related disability, interventions targeting these factors—particularly insomnia—could reduce disability and enhance quality of life in those who suffer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain is a common complaint that affects a substantial portion of the population1. In Norway chronic pain touches the lives of approximately one in three adults2. Unlike short-lived acute pain, which tends to fade as the underlying cause resolves, chronic pain is characterized by its persistence, often transitioning into a long term condition after the first year3. In addition to pain duration and other temporal aspects, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) suggest location, pain quality and pain intensity as the major “axes of pain”4. Chronic pain can be further classified into two categories in the recent ICD-11 taxonomy: primary pain, which lacks clear underlying causes, and secondary pain, which emerges as a symptom of an underlying disease5. Both forms of chronic pain play a significant role in prolonged sick leave and work-related disability6.

Pain, defined as an “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage”7, is influenced not only by physical sensations but also by psychological and social factors8. Since purely biomedical treatments are limited in their effectiveness for chronic pain, the understanding of psychological and social dimensions becomes increasingly important. People living with chronic pain not only contend with the burden of physical symptoms but also face its impact on daily functioning, commonly referred to as pain-related disability9. To refine treatments and prevent pain-related disability in individuals with chronic pain, we need to comprehensively explore psychosocial aspects10 in addition to the pain axes.

The association between pain intensity and the impact on functional abilities, referred to as pain-related disability, remains uncertain due to the inconsistent findings in existing research11. This uncertainty suggests that factors beyond pain intensity, such as widespread pain and psychosocial co-morbidity, significantly contribute to pain-related disability12,13. Studies have indicated that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can reduce disability by diminishing maladaptive responses like pain-related fear and catastrophizing, while strengthening self-efficacy. However, the effectiveness of CBT in reducing pain intensity does not appear to outperform that of control treatments14. Consequently, further research is essential to gain a better understanding of the factors influencing pain-related disability.

Various models have been developed to understand the interplay between pain experience and behaviour, with the fear-avoidance model being one of the most established15. According to this model, individuals in pain may develop excessive fear and avoidance behaviors due to their perceptions and beliefs about pain. This fear and avoidance contribute to the exacerbation and perpetuation of pain-related disability16. While fear can serve as an adaptive response to acute pain, excessive focus on pain and catastrophic thinking can result in maladaptive cognitive and behavioural responses17. Pain catastrophizing, characterized by negative rumination, plays a crucial role in predicting chronic pain18. It triggers unconscious fear and fosters pain-avoidant behaviours19. The model underscores the importance of addressing and breaking this destructive cycle of fear and avoidance for improving pain-related outcomes. Avoidance of pain-triggering situations predicts pain-related disability and is often accompanied by negative expectations and emotions20. Individuals who engage in extensive pain catastrophizing tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity in the short term but are also at a greater risk of developing chronic pain and pain-related disability in the long term18,21.

Psychological distress is recognized as a risk factor for the development of chronic pain22, and persistent psychological distress and lifetime stressors are particularly implicated in the progression of chronic pain23,24. Additionally, pain-related injustice, characterized by negative appraisals of pain-related losses and unfairness, has consequences for prognoses and treatment outcomes25. It fosters hypervigilance toward pain and exacerbates the pain experience26. The impact of various forms of psychological distress can vary and influence the extent and duration of disability27,28.

Psychological distress can also initiate and perpetuate physiological stress activation. The Cognitive Activation Theory of Stress (CATS) theory offers insights into how stress impacts health29. According to CATS, individuals´ perceptions and interpretations of perceived stressors are crucial. When individuals feel helpless or hopeless, the stress responses will persist, potentially leading to illness or disease. Furthermore, a bidirectional relationship exists between chronic stress and sleep disturbances, particularly insomnia, which is prevalent in chronic pain patients30 and often results in fatigue31, a common complaint among individuals with chronic pain32. Recent studies have also revealed the predictive value of sleep disturbances and fatigue33,34, warranting further investigation in diverse pain populations.

On the other hand, self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to perform tasks or achieve goals35, appears to serve as a buffer against heightened stress levels. This belief enhances motivation and shapes the pain experience by fostering confidence in one’s ability to influence their suffering35. Improved pain-related self-efficacy is associated with enhanced coping abilities36. Furthermore, resilience plays a vital role in buffering against stressors that could impact the pain experience.

Studies have consistently linked the mentioned factors to adverse outcomes for people with pain, except for self-efficacy, which tends to have the opposite effect and be beneficial19,25,28,37. A recent meta-analysis found for instance support for the various components of the fear-avoidance model in patients with chronic pain, where fear of pain, pain catastrophizing, and pain vigilance, were all strongly associated with negative affect, anxiety, pain intensity, and disability38. Similar findings were reported in a systematic review focused on studies of musculoskeletal pain, which identified an association between increased pain-related fear and anxiety and higher levels of pain intensity and disability39. Alamam et al.40 extended this research to show that across cultures and regions, beliefs about pain, including self-efficacy, pain catastrophizing, and pain-related fear, were associated with disability due to low back pain40. Other studies have focused more specifically on the association between pain and disability. Here, self-efficacy, psychological distress, and fear were identified as mediators in the relationship between pain and disability, although catastrophizing did not show a mediating effect in this meta-analysis41.

Despite these insights, it is important to note that most current studies have focused on musculoskeletal pain, particularly back pain. There is as such a need to investigate how these associations hold in more general pain populations to better understand the broader implications of psychosocial factors on pain-related disability.

Building on previous studies, we hypothesize that various psychosocial factors—such as pain catastrophizing, psychological distress, perceived injustice, insomnia, fatigue, and self-efficacy—are linked to pain-related disability in patients with chronic pain. In our study, we seek to enhance the existing literature by confirming the already established significant relationship in a large, real world Norwegian patient cohort of patients with diverse chronic pain conditions referred to a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Additionally, as an exploratory analysis, we aim to assess how indicators of chronicity, such as work status and duration of pain, moderate these relationships42. To investigate these relationships, we have formulated three research questions:

-

1.

How do various psychosocial factors correlate with pain-related disability in chronic pain patients?

-

2.

Do these relationships differ depending on work disability status (temporary vs permanent financial disability benefits) or pain duration (< 1 vs ≥ 1 year)?

-

3.

What proportion of the variance in pain-related disability can be explained by these psychosocial factors collectively?

Methods

Sample

We utilized questionnaire data from the Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry, which includes information from all patients dealing with chronic pain and attending the Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry, totaling 4285 patients. This data was collected between October 2015 and March 202043. The patients were referred to the registry from general practitioners or specialist health care services and received treatment within the South-Eastern Health region of Norway, encompassing Oslo, the country’s largest city. The data collection occurred in a naturalistic clinical audit setting. Some patients were given the option to choose between a comprehensive questionnaire package and a shorter version, which included only a few selected scales to reduce the potential survey burden.

This patient population was notably diverse, representing a range of chronic pain conditions, including those related to cancer, heart disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and various subacute pain conditions. These conditions encompassed cases with and without a known explicit cause. It’s worth noting that non-malignant cases were overrepresented44. Another study conducted on the same cohort (n = 2799) reveals that patients with primary pain constitute more than half of the patient population45. The overview is as follows: Chronic primary pain 52.5% (n = 1469), Chronic cancer-related pain 0.3% (n = 8), Chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain 6.4% (n = 178), Chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain 12% (n = 335), Chronic secondary visceral pain 1.4% (n = 38), Chronic neuropathic pain 16.3% (n = 456), Chronic secondary headache or orofacial pain 0.3% (n = 8) and Unspecified chronic pain 11% (n = 307).

Measures

The patients supplied demographic information, including their age (in years), gender (male/female), level of education (primary, secondary, short tertiary, and long tertiary), employment status (working vs non-working), length of time spent out of work (in years), degree of partial or full financial benefits (Group 1: “Sick pay” up to 1 year and “Work assessment allowance/AAP” up to 4 years or Group 2: “Permanent benefit”). Additionally, they reported the duration of their pain. Since research suggest that neural networks undergo significant changes within the initial year of experiencing pain, and thereafter stabilizing3, pain duration was recoded into less than a year versus one year or more43.

Independent variables

Pain intensity and bothersomeness: Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

The NRS questionnaire consists of two items assessing pain intensity and pain bothersomeness. For instance, it evaluates the pain experienced last week in terms of its highest, average, and lowest intensity, as well as the current pain level46,47. Pain intensity and pain bothersomeness are significantly correlated (r = 0.698, n = 3836, p ≤ 0.001), yet they measure different aspects of pain, representing two separate dimensions of the pain experience and therefore both are included. Each question offers 11 response options, spanning from 0 (“No pain at all”) to 10 (“Worst pain possible”)46. Mild pain intensity typically ranges from 1 to 3, moderate pain intensity ranges from 4 to 6, while scores of 7 and above are considered severe pain intensity48. There are no established cutoff scores for bothersomeness. The NRS has been established as a reliable and valid measure49. The two pain intensity and bothersomeness measures are based on the well-validated Brief Pain Inventory50, which has also been validated in Norwegian51.

Catastrophizing: Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)

The PCS is a 13-item scale that measures pain catastrophizing, meaning “an exaggerated negative mental set brought to bear during actual or anticipated painful experience”52. Each question offers five response options, ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “All the time” (4), with a higher score indicating more intense pain catastrophizing. The scores range from 0 to 52, with individuals scoring 24 points or more being considered catastrophizers and those scoring below 15 points being considered non-catastrophizer52. The PCS has demonstrated reliability and validity, including a Norwegian validation53. In this cohort, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Psychological distress: Hopkins Symptom Check List-25 (HSCL-25)

The HSCL-25 is a 25-item questionnaire that evaluates psychological distress encompassing anxiety, depression and somatization54. Each question provides four different response options, ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Extremely”), with higher total scores indicating greater psychological distress. An HSCL-25 mean score of 1.75 or above suggests the need for treatment55. The HSCL-25 is established as a reliable and valid tool and has been validated in Norwegian55. In this cohort, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

Perceived injustice: Injustice Experience Questionnaire (IEQ)

The IEQ is a 12-item questionnaire that measures the degree to which patients with chronic pain perceive injustice about their pain condition. It presents respondents with statements reflecting notions of blame or unfairness, as well as the severity and perceived irreparability of the associated losses56. Each question has five response options ranging from “Never” (0) to “All the time” (4)56. The scores range from 0 to 48, with scores above 19 (medium IEQ) predicting both increased pain severity and more work-related disability, and a cutoff score of 30 (high IEQ) being considered clinically relevant25. The IEQ has exhibited reliability and validity in previous studies57 and has been validated in Norwegian58. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92 in this cohort.

Insomnia: Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

The ISI is a 7-item questionnaire that assesses insomnia symptoms over the past couple of weeks59. This comprehensively examines the nature, severity, and impact of insomnia symptoms, providing insights into the individual’s sleep disturbances and their consequences. Each question has five response options, spanning from 0 (“None”/“Very happy”) to 4 (“Very/Very unhappy”), with higher scores indicating more severe insomnia symptoms. The scores range from 0 to 28, with scores at or above 15 being considered moderate (15–21) to severe (22–28) insomnia59. The ISI is known to have high reliability and validity59 and has been validated in Norwegian60. In this cohort, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Fatigue: Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ)

The CFQ is an 11-item questionnaire that measures fatigue, encompassing both physical and mental aspects61. Each question offers four response options, ranging from “Less than usual” (0) to “Much more than usual” (3). Following Chalder’s procedure, each item was dichotomized so that respondents answering 2 or 3 were considered “cases” for that particular question, and those answering 0 or 1 were considered non-cases. The total score ranges from 0 to 11, with scores of 4 or above indicating severe fatigue62. The CFQ has been established as a reliable and valid measure61 and has been validated in Norwegian63. In this cohort, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Self-efficacy: General Self-Efficacy scale (GSE)

The GSE is a 10-item questionnaire that measures perceived self-efficacy, regardless of morbidity and disability64. Each question has four response options, ranging from 1 (“Not at all true”) to 4 (“Exactly true”), with higher scores indicating greater perceived self-efficacy64. The scores range from 0 to 4, and is usually found to average 2.9 across various samples65. The GSE has been validated as reliable and valid and has been validated in Norwegian66. In this cohort, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Dependent variable: pain-related disability, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)

The ODI is a 10-item questionnaire that measures pain-related disability across ten dimensions of daily functioning: pain intensity, personal care, lifting, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, sexual activity, social engagement, and travel9. The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry employs a modified version of the questionnaire by omitting the word “back” from the question in the introduction43. Each question offers six different response options, ranging from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more disability. The score is rescaled to range from 0 to 100%. Scores between 0 and 20% indicate minimal disability, scores between 21 and 40% indicate moderate disability, scores between 41 and 60% indicate severe disability, scores between 61 and 80% indicate being crippled, and finally, scores between 81 and 100% indicate either being bedbound or exaggerating symptoms9. The ODI is established as a reliable and valid tool9 and has been validated in the original version in Norwegian67. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86 in this questionnaire.

Missing data

For each scale, we calculated the mean score for each participant. Participants who responded to less than 50% of the questions were considered as non-respondents. Afterwards, we rescaled all the scales to their original range. For each regression model, we used listwise deletion.

Ethical considerations

The present study employs a dataset from a comprehensive patient registry, and the specific data provided to us were fully anonymized. Research protocols involving anonymized data in Norway are exempt from the requirement of formal review and approval by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). Complying with these regulations, our project did not necessitate a formal ethics review by the Regional Ethical Committee. Despite this exemption, we have nevertheless conducted our research with a deep commitment to ethical practices. We have implemented rigorous internal ethical reviews to ensure the highest standards of integrity throughout our research. This included verifying that all data used were collected from participants who had given explicit consent for their utilization in research, thereby upholding their rights and autonomy. Moreover, we have taken extensive measures to maintain the security and confidential handling of the research data. Throughout this process, and into the dissemination of our findings, we are dedicated to the ethical principle of honesty and clarity, ensuring that our research is communicated accurately and transparently.

Statistical analysis

We conducted the analysis using SPSS version 27 and reported descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and standard deviations (Tables 1, 2). Figures was made in R using the ggplot function.

To explore the relationship between psychosocial indicators and pain-related disability, we calculated both bivariate and adjusted regression coefficients, with pain-related disability as the dependent variable. Standardized regression coefficients are presented in the figures, while unstandardized coefficients can be found in Table 3 (for unadjusted coefficients, please see Table 3—Supplementary Table S1 provides additional details). Our adjustments included controlling for age, gender, education level (treated as a continuous), and work status (for adjusted coefficients, consult Table 3—see also Supplementary Table S2).

To investigate whether the associations between psychosocial variables and pain-related disability were influenced by financial disability benefit status or pain duration, we used hierarchical regression analyses with interaction terms in separate models, while maintaining control for age, gender, education level, and work. In step 1, we standardized all variables, both independent and dependent, except for the moderators “financial benefit” and “pain duration”, as they are categorical variables. In step 2, we created interaction terms/product terms. In step 3, we conducted a linear regression. We carried out this process as two models. The first model included the control variables. The second model included one interaction term at a time. First, we examined financial disability benefit status, categorizing it into two groups: temporary financial disability benefits and permanent financial disability benefits (see Supplementary Table S3). Individuals who did not receive either temporary or permanent benefits were excluded from this model. Second, we assessed pain duration, categorizing it into two groups: short-term pain-duration (< 1 year) and long-term pain duration (≥ 1 year) (see Supplementary Table S4).

Finally, we evaluated the unique contributions of the included psychosocial measures in explaining the variance in pain-related disability scores. We accomplished this by including all variables in a single regression model, along with the covariates (Table 4), while also checking for multicollinearity.

AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to enhance language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The sample consisted of 4285 participants, with women accounting for the majority at 58.1% (n = 2490). The average age of the participants was 49.5 years (SD = 15.59, n = 4285). Approximately 39% (n = 1673) had completed college or university education. A substantial portion, 60.5% (n = 2592), were currently unemployed, while 46.3% (n = 1985) having been out of work for more than two years. Among those not employed, the average duration of unemployment was 10.8 years (SD = 9.72, n = 1847). For the employed participants, the average Full-Time Equivalent percentage was 78.5% (n = 1251).

Around one-third of the participants (36.3%, n = 1553) received temporary financial disability benefits, and another one-third (27.8%, n = 1190) received permanent financial disability benefit. A large majority had experienced pain for one year or more (88.1%, n = 3776). A summary of these sample characteristics is available in Table 1.

In terms of pain-related measures, mean pain intensity (M 7.17, SD 1.80, n = 3840) and pain bothersomeness (M 7.70, SD 1.74, n = 3836) exceeded clinically relevant thresholds. Pain-related disability, on average, was severe (42.7%, SD 17.47, n = 4249). Most participants reported levels of pain catastrophizing (M 23.86, SD 12.68, n = 3733), psychological distress (M 2.15, SD 0.59, n = 3879), and perceived injustice (M 23.68, SD 11.36, n = 3742) that indicated a need for treatment. Average insomnia levels were moderate (M 15.44, SD 6.74, n = 3770), with 51.4% reporting clinically relevant insomnia (i.e., score > 15). Similarly, the average level of fatigue was 6.81 (SD 3.26, n = 3776). On the other hand, self-efficacy was within the normal range compared to samples from the general population (M 2.86, SD 0.56, n = 3769). Descriptive statistics for these psychosocial factors are visualized in Fig. 1. Further details are provided in Table 2.

Analyses

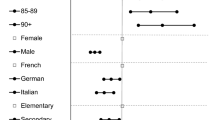

We identified strong associations in the bivariate regressions between all psychosocial variables and pain-related disability, with associations ranging from 0.31 to 0.46 (shown in orange in Fig. 2). These associations remained significant and robust even after adjusting for demographic variables in the bivariate regressions (displayed in yellow in Fig. 2). For detailed results see Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Table S1 and S2.

The results from the moderation analyses, conducted using hierarchical regression analyses with interaction terms, revealed only a few significant differences, none of which were large (see Fig. 3). Pain duration played a moderating role for pain bothersomeness (< 0.001) and pain catastrophizing (p = 0.013) on pain-related disability, with slightly stronger associations among individuals who had experienced pain for less than one year than for a year or more. Financial benefits did not moderate any of the associations. For full results, please see Supplementary Table S3 and S4.

When we included all psychosocial variables (including pain intensity) in the multiple regression model, while also being adjusted for gender, age, education, and employment we found that they collectively explained 40.9% (r2 = 0.409) (covariates 14.4%, (r2 = 0.144) and psychosocial variables 26.5%) of the total variance in pain-related disability (F (12,3308) = 191.089, p < 0.000). Most associations were unsurprisingly substantially reduced (shown in blue in Fig. 2). Following an examination for multicollinearity, it was observed that all Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) remained below 3, representing a conservative threshold. This analysis indicates the absence of significant multicollinearity concerns among the predictor variables in the regression model, thereby negating the necessity for variable removal. Notably, insomnia and pain intensity were the most strongly associated with pain-related disability when adjusting for all the psychosocial factors. For more information, see Table 4.

Discussion

As hypothesized, we found significant correlations between all the included psychosocial variables we investigated and pain-related disability. These associations remained robust even after adjusting for common demographic factors such as age, gender, education level, and work status. These findings align with previous research, suggesting that psychosocial variables have a central role in pain-related disability.

The correlation between pain intensity and pain-related disability was smaller than anticipated. One might intuitively assume a stronger relationship between pain intensity and disability when a questionnaire specifically addresses pain-related limitations. Typically, as pain intensity increases, the level of disability would also increase. However, the smaller-than-expected correlation implies that additional factors play a significant role in influencing pain-related disability. This underscores the importance of investigating different factors as potential contributors to the complex relationship between pain and disability.

We also found that pain-related disability was about equally correlated with psychological distress as with pain intensity. This relationship may be reciprocal, but the finding aligns with previous research showing that individuals with higher distress levels report elevated pain intensity and pain-related disability19. Furthermore, we found a significant correlation between perceived injustice and pain-related disability, which was also at a similar level as pain intensity and pain-related disability. This suggests that this relatively underexplored factor may exert a relevant influence, with the caveat that the causality of this relationship remains uncertain. Perceived injustice encompasses worry or concern, feelings of helplessness, and negative outlooks for the future. This factor is known to correlate with catastrophic thinking about pain25. These thought patterns can lead to the monitoring of pain signals, thereby exacerbating the pain experience and contributing to the vicious circle elucidated by the fear-avoidance model. Importantly, our observations regarding the relationship between perceived injustice and pain-related disability are consistent with findings from previous studies25. Notably, a recent systematic review reported significant associations between perceived injustice and pain intensity and disability68.

Fear, worry and helplessness can trigger physiological responses trough the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, the body’s “fight or flight” response29. Chronic stress activation, characterized by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness as opposed to coping, can have profound implications for health, such as cardiovascular issues, immune system dysfunction, and even sleep disturbances, such as insomnia or disrupted sleep patterns, similar to pain-mechanisms in social rejection contexts27. Insomnia is often an early sign of persistent stress, but the relationship may be bidirectional. Prolonged stress can lead to poor sleep, while inadequate sleep can trigger stress. In our study, we observed a strong association between sleep problems and pain-related disability, about as strong as for pain-intensity. The association is consistent with previous research showing that individuals with chronic pain often experience sleep disturbances30. Furthermore, it’s worth noting that research suggest a potential link between poor sleep and increased pain sensitivity69.

The Cognitive Activation Theory of Stress (CATS) also serves as a foundational framework for understanding the relationship between physical activation and fatigue70. This state of persistent activation can result in poor sleep patterns, but also trigger automatic and adaptive “alarms”, leading to behavioral changes, such as the emergence of symptoms like pain or fatigue. Chronic stress activation can also lead to psychological effects like worry and rumination, contributing to persistent activation and ultimately fatigue. Notably, since fatigue is common among individuals with chronic pain, with 60–70% reporting co-occurring persistent fatigue34,71, the association between fatigue and pain-related disability in our study was expected. Additionally, psychological distress and pain are closely related to fatigue; the longer and more intense pain the more pronounced the fatigue72. While fatigue was indeed associated with pain-related disability, the relationship between catastrophizing, psychological distress, perceived injustice, sleep problems and pain-related disability was even stronger. These results are in line with earlier literature but challenge previous perceptions that pain intensity is the primary driver of pain-related disability.

Self-efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s ability to cope with challenges, can positively impact various psychosocial factors and pain-related disability73. General self-efficacy, as measured in this study, encompasses aspects of optimism and coping with life in general, rather than specifically focusing on pain-related self-efficacy. It is important to discuss the implications and limitations of using general self-efficacy in a chronic pain population. Few studies have examined general self-efficacy in the context of chronic pain to determine whether it represents domain-specific coping or general coping skills and how it correlates with functional outcomes. Our study identified a negative correlation between self-efficacy and pain-related disability, indicating that low self-efficacy is associated with increased pain-related disability. This observation is in line with previous research suggesting that self-efficacy mediates the impact of pain intensity on pain-related disability73.

The observed interaction between pain duration, pain bothersomeness, and pain-related disability is a noteworthy finding. It suggests that as pain persists over time, the perceived bothersomeness of the pain may gradually diminish in its impact on daily functioning. One might speculate that individuals experiencing chronic pain may develop adaptive mechanisms or coping strategies over time, which allow them to better manage and adapt to the presence of persistent pain. These adaptations might reduce the perceived interference of pain with their daily lives. Additionally, it highlights the dynamic nature of pain experiences and the need to consider how pain perceptions and their impact may evolve with longer pain durations.

When evaluating the combined contribution of psychosocial factors to the variation in pain-related disability, we found that these factors accounted for a quarter of the variance. Sleep problems and pain intensity emerged as primary contributors, complemented by psychological distress and fatigue. Notably, the contribution of pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice and self-efficacy were non-significant in the combined regression model, which contrasts with the typical significance of pain catastrophizing in overall regression models. One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be the inclusion of sleep and/or fatigue variables, which may not be as commonly examined. This does not necessarily diminish their importance but may suggest that they may be overshadowed when combined in a multiple regression model. Another possibility is that pain catastrophizing indeed plays a smaller role than other psychosocial variables when it comes to pain-related disability. Supporting this perspective, a systematic review by Lee et al.41 revealed that pain catastrophizing did not mediate the link between pain intensity and disability, which contradicts its mediating role in experimental treatment studies74. Lee et al. speculate that while catastrophizing may mediate treatment effects, it may be less important for disability development. This intriguing disparity warrants further exploration.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that the findings from our multiple regression model, while significant, provide just a piece of the full puzzle. Pain-related disability is a multifaced outcome influenced by a range of factors, and our study concentrated on the psychosocial aspects. Many other variables are likely to influence pain-related disability. These include underlying medical conditions, lifestyle factors, cultural influences, and social determinants. The relative scarcity of social variables in our analysis is a particular issue that should be followed up in future studies. Understanding the multifaceted relationship between pain intensity, psychosocial variables, and pain-related disability is still crucial for developing more comprehensive and effective interventions in the field of pain management and rehabilitation.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

Our study offers several notable strengths. It benefits from a substantial sample size, drawn from a real-world environment at Norway’s largest multidisciplinary pain clinic. The research is underpinned by the application of validated questionnaires and is firmly grounded within a robust theoretical framework. Nevertheless, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the cross-sectional nature of our study design precludes the ability to infer causality between the variables assessed. Additionally, the predominance of psychological over social variables in our analysis represents a limitation. Future investigations should aim to incorporate a broader selection of social variables to more fully elucidate the psychosocial dimensions at play. Regarding treatment implications, there are several opportunities to explore promising interventions. Treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia and Pain Reprocessing Therapy have demonstrated great potential75,76 that merits further exploration in pain clinic populations. Furthermore, we advocate for a broader approach to interventions. Comprehensive strategies should not only tackle psychosocial factors but should also encompass a holistic perspective on pain management and disability prevention. Recognizing the significant role of psychosocial factors as modifiable prognostic elements77, future research should delve into multifaceted approaches that take into account the interconnected nature of pain intensity, psychological distress, and insomnia.

Conclusion

In summary, our cross-sectional bi-variate analyses revealed significant associations between pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, psychological distress, perceived injustice, sleep, fatigue, and self-efficacy with pain-related disability, aligning with previous research. In the multiple regression model, sleep problems and pain intensity were identified as primary contributors, alongside psychological distress, and fatigue. Interestingly, pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and self-efficacy did not show significant contributions in the combined regression model, which contrasts most previous findings. While the direction of causation remains unclear, these findings emphasize the potential for interventions targeting these psychosocial factors to be more effective in improving the lives of individuals with chronic pain compared to solely focusing on pain management.

Data availability

The data utilized in this study are sourced from the Oslo Pain Registry (OPR). Access to the dataset is granted through the OPR board. Requests to access the data should be directed to chrekh@ous-hf.no.

Code availability

SPSS version 27.

References

Breivik, H., Collett, B., Ventafridda, V., Cohen, R. & Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain 10, 287–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 (2006).

Landmark, T. et al. Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study). Scand. J. Pain 4, 182–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.07.022 (2013).

Hashmi, J. A. et al. Shape shifting pain: Chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain 136, 2751–2768. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt211 (2013).

Merskey, H. & Bogduk, N. Classification of Chronic Pain (IASP Press, 1994).

World Health Organization. International Classiffication of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). https://icd.who.int/en (2022).

Valentin, G. H. et al. Prognostic factors for disability and sick leave in patients with subacute non-malignant pain: A systematic review of cohort studies. BMJ Open 6, e007616. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007616 (2016).

International Association for the Study of Pain. Terminology. https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (2020).

Hadjistavropoulos, T. & Craig, K. D. In Pain: Psychological Perspectives (eds Hadjistavropoulos, T. & Craig, K. D.) 1–12 (Psychology Press, 2004).

Fairbank, J., Couper, J., Davies, J. B. & O’Brien, J. P. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 66, 271–273 (1980).

Martikainen, P., Bartley, M. & Lahelma, E. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 31, 1091–1093 (2002).

Shaw, W. S., Pransky, G. & Winters, T. The back disability risk questionnaire for work-related, acute back pain: Prediction of unresolved problems at 3-month follow-up. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 51, 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e318192bcf8 (2009).

Landrø, N. I. et al. The extent of neurocognitive dysfunction in a multidisciplinary pain centre population. Is there a relation between reported and tested neuropsychological functioning? Pain 154, 972–977 (2013).

Vera Cruz, G. et al. Machine learning reveals the most important psychological and social variables predicting the differential diagnosis of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Rheumatol. Int. 42, 1053–1062 (2022).

Murillo, C. et al. How do psychologically based interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain work? A systematic review and meta-analysis of specific moderators and mediators of treatment. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 94, 102160 (2022).

Vlaeyen, J. W. & Linton, S. J. Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain 153, 1144–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.009 (2012).

Zale, E. L. & Ditre, J. W. Pain-related fear, disability, and the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 5, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.014 (2015).

Quartana, P. J., Campbell, C. M. & Edwards, R. R. Pain catastrophizing: A critical review. Expert Rev. Neurotherap. 9, 745–758. https://doi.org/10.1586/ERN.09.34 (2009).

Martinez-Calderon, J., Jensen, M. P., Morales-Asencio, J. M. & Luque-Suarez, A. Pain catastrophizing and function in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. J. Pain 35, 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000676 (2019).

Feinstein, A. B. et al. The effect of pain catastrophizing on outcomes: A developmental perspective across children, adolescents, and young adults with chronic pain. J. Pain 18, 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.009 (2017).

Van Damme, S., Crombez, G. & Eccleston, C. Coping with pain: A motivational perspective. Pain 139, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.022 (2008).

Arnow, B. A. et al. Catastrophizing, depression and pain-related disability. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 33, 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.12.008 (2011).

Pincus, T., Burton, A. K., Vogel, S. & Field, A. P. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Orthop. Proc. 84, 142–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200203010-00017 (2002).

Shaw, W. S., Hartvigsen, J., Woiszwillo, M. J., Linton, S. J. & Reme, S. E. Psychological distress in acute low back pain: A review of measurement scales and levels of distress reported in the first 2 months after pain onset. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 97, 1573–1587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.02.004 (2016).

Kaleycheva, N. et al. The role of lifetime stressors in adult fibromyalgia: Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Psychol. Med. 51, 177–193 (2021).

Reme, S. E. et al. Perceived injustice in patients with chronic pain: Prevalence, relevance, and associations with long-term recovery and deterioration. J. Pain. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2022.01.007 (2022).

Vlaeyen, J. W. & Linton, S. J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain 85, 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0 (2000).

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D. & Williams, K. D. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science 302, 290–292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089134 (2003).

Severeijns, R., Vlaeyen, J. W., van den Hout, M. A. & Weber, W. E. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability, and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Clin. J. Pain 17, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200106000-00009 (2001).

Ursin, H. & Eriksen, H. R. The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00091-X (2004).

Sivertsen, B., Krokstad, S., Øverland, S. & Mykletun, A. The epidemiology of insomnia: Associations with physical and mental health: The HUNT-2 study. J. Psychosom. Res. 67, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.001 (2009).

Sivertsen, B., Hysing, M., Harvey, A. G. & Petrie, K. J. The epidemiology of insomnia and sleep duration across mental and physical health: The SHoT study. Front. Psychol. 12, 2309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662572 (2021).

Hiestand, S., Forthun, I., Waage, S., Pallesen, S. & Bjorvatn, B. Associations between excessive fatigue and pain, sleep, mental-health and work factors in Norwegian nurses. PLoS ONE 18, e0282734. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282734 (2023).

Miettinen, T. et al. Sleep problems in pain patients entering tertiary pain care: The role of pain-related anxiety, medication use, self-reported diseases, and sleep disorders. Pain 163, e812–e820. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002497 (2022).

Van Damme, S., Becker, S. & Van der Linden, D. Tired of pain? Toward a better understanding of fatigue in chronic pain. Pain 159, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001054 (2018).

Bandura, A., O’leary, A., Taylor, C. B., Gauthier, J. & Gossard, D. Perceived self-efficacy and pain control: Opioid and nonopioid mechanisms. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 53, 563. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.563 (1987).

Matos, M., Bernardes, S. F., Goubert, L. & Beyers, W. Buffer or amplifier? Longitudinal effects of social support for functional autonomy/dependence on older adults’ chronic pain experiences. Health Psychol. 36, 1195. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000512 (2017).

Martinez-Calderon, J., Jensen, M. P., Morales-Asencio, J. M. & Luque-Suarez, A. Pain catastrophizing and function in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin. J. Pain 35, 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000676 (2019).

Rogers, A. H. & Farris, S. G. A meta-analysis of the associations of elements of the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain with negative affect, depression, anxiety, pain-related disability and pain intensity. Eur. J. Pain 26, 1611–1635 (2022).

Martinez-Calderon, J., Flores-Cortes, M., Morales-Asencio, J. M. & Luque-Suarez, A. Pain-related fear, pain intensity and function in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain 20, 1394–1415 (2019).

Alamam, D. M. et al. Low back pain-related disability is associated with pain-related beliefs across divergent non-English-speaking populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med. 22, 2974–2989 (2021).

Lee, H. et al. How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain 156, 988–997 (2015).

Jacobsen, H. B. et al. Describing patients with a duration of sick leave over and under one year in Norway. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 22, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2014.957241 (2015).

Granan, L.-P., Reme, S. E., Jacobsen, H. B., Stubhaug, A. & Ljoså, T. M. The Oslo University Hospital Pain Registry: Development of a digital chronic pain registry and baseline data from 1712 patients. Scand. J. Pain 19, 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2017-0160 (2019).

Oslo University Hospital. Elektronisk kartlegging—OUS Smerteregister. https://oslo-universitetssykehus.no/fag-og-forskning/nasjonale-og-regionale-tjenester/regional-kompetansetjeneste-for-smerte-reks/elektronisk-kartlegging-ous-smerteregister (2020).

Munk, A., Jacobsen, H. B. & Reme, S. E. Coping expectancies and disability across the new ICD-11 chronic pain categories: A large-scale registry study. Eur. J. Pain 26, 1510–1522. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1979 (2022).

Williamson, A. & Hoggart, B. Pain: A review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 14, 798–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x (2005).

Jacobsen, B. K., Eggen, A. E., Mathiesen, E. B., Wilsgaard, T. & Njølstad, I. Cohort profile: The Tromsø study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 961–967 (2012).

Breivik, H. et al. Assessment of pain. Br. J. Anaesth. 101, 17–24 (2008).

Jensen, M. P., Karoly, P. & Braver, S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: A comparison of six methods. Pain 27, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9 (1986).

Keller, S. et al. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin. J. Pain 20, 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005 (2004).

Klepstad, P. et al. The Norwegian brief pain inventory questionnaire: Translation and validation in cancer pain patients. J. Pain Sympt. Manag. 24, 517–525 (2002).

Sullivan, M. J., Bishop, S. R. & Pivik, J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 7, 524. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524 (1995).

Fernandes, L., Storheim, K., Lochting, I. & Grotle, M. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Norwegian pain catastrophizing scale in patients with low back pain. BMC Musculoskel. Disord. 13, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-13-111 (2012).

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H. & Covi, L. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav. Sci. 19, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830190102 (1974).

Sandanger, I. et al. The meaning and significance of caseness: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 and the composite international diagnostic interview II. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 34, 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050112 (1999).

Sullivan, M. J. et al. The role of perceived injustice in the experience of chronic pain and disability: Scale development and validation. J. Occup. Rehabil. 18, 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9140-5 (2008).

Rodero, B. et al. Perceived injustice in fibromyalgia: Psychometric characteristics of the injustice experience questionnaire and relationship with pain catastrophising and pain acceptance. J. Psychosom. Res. 73, 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.05.011 (2012).

Ljosaa, T. M., Berg, H. S., Jacobsen, H. B., Granan, L.-P. & Reme, S. Translation and validation of the Norwegian version of the injustice experience questionnaire. Scand. J. Pain 22, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2021-0177 (2022).

Morin, C. M., Belleville, G., Bélanger, L. & Ivers, H. The insomnia severity index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 34, 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.5.601 (2011).

Pallesen, S. et al. A new scale for measuring insomnia: The Bergen insomnia scale. Percept. Motor Skills 107, 691–706. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.107.3.691-706 (2008).

Chalder, T. et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 37, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p (1993).

Jackson, C. The Chalder fatigue scale (CFQ 11). Occup. Med. 65, 86–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu168 (2015).

Loge, J. H., Ekeberg, Ø. & Kaasa, S. Fatigue in the general norwegian population. J. Psychosom. Res. 45, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00291-2 (1998).

Schwarzer, R. & Jerusalem, M. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs Vol. 35 (eds Wright, S. et al.) 37 (Springer, 1995).

Schwarzer, R. Everything You Wanted to Know About the General Self-Efficacy Scale but were Afraid to Ask. https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/faq_gse.pdf (2014).

Røysamb, E., Schwarzer, R. & Jerusalem, M. Norwegian Version of the General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale. https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/norway.htm (1998).

Grotle, M., Brox, J. & Vollestad, N. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Norwegian versions of the Roland–Morris disability questionnaire and the oswestry disability index. J. Rehabil. Med. 35, 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/16501970306094 (2003).

Carriere, J. S., Donayre Pimentel, S., Yakobov, E. & Edwards, R. R. A systematic review of the association between perceived injustice and pain-related outcomes in individuals with musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 21, 1449–1463. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa088 (2020).

Sivertsen, B. et al. Sleep and pain sensitivity in adults. Pain 156, 1433–1439. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000131 (2015).

Wyller, V. B., Eriksen, H. R. & Malterud, K. Can sustained arousal explain the chronic fatigue syndrome? Behav. Brain Funct. 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-5-10 (2009).

Creavin, S. T., Dunn, K. M., Mallen, C. D., Nijrolder, I. & van der Windt, D. A. Co-occurrence and associations of pain and fatigue in a community sample of Dutch adults. Eur. J. Pain 14, 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.05.010 (2010).

Løke, D. et al. The role of pain and psychological distress in fatigue: A co-twin and within-person analysis of confounding and causal relations. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 10, 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2022.2033121 (2022).

Martinez-Calderon, J., Zamora-Campos, C., Navarro-Ledesma, S. & Luque-Suarez, A. The role of self-efficacy on the prognosis of chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. J. Pain 19, 10–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.08.008 (2018).

Mansell, G., Kamper, S. J. & Kent, P. Why and how back pain interventions work: What can we do to find out? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 27, 685–697 (2013).

Vedaa, Ø. et al. Effects of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia on insomnia severity: A large-scale randomised controlled trial. Lancet Dig. Health 2, e397–e406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30135-7 (2020).

Ashar, Y. K. et al. Effect of pain reprocessing therapy vs placebo and usual care for patients with chronic back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 13–23 (2022).

Tseli, E. et al. Prognostic factors for physical functioning after multidisciplinary rehabilitation in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. J. Pain 35, 148. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000669 (2019).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The study did not receive any financial support or funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: SER and LL. Statistical analyses: LL and HFS. HFS prepared figures. Draft manuscript preparation: LL. All authors reviewed and contributed to the interpretation of the results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

LL receives honorarium for lectures about stress and coping. SER receives honorariums for lectures and workshops about stress and pain. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest relating to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Landmark, L., Sunde, H.F., Fors, E.A. et al. Associations between pain intensity, psychosocial factors, and pain-related disability in 4285 patients with chronic pain. Sci Rep 14, 13477 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64059-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64059-8

- Springer Nature Limited