Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a prominent global health challenge, characterized by a rising prevalence and substantial morbidity and mortality, especially evident in developing nations. Although DM can be managed with self-care practices despite its complexity and chronic nature, the persistence of poor self-care exacerbates the disease burden. There is a dearth of evidence on the level of poor self-care practices and contributing factors among patients with DM in the study area. Thus, this study assessed the proportion of poor self-care practices and contributing factors among adults with type 2 DM in Adama, Ethiopia. An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 404 patients. Self-care practice was assessed by the summary of diabetes self-care activities questionnaires. Binary logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with poor self-care practices. An adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used to assess the strength of associations. The statistical significance was declared for a p-value < 0.05. The proportion of poor self-care practices was 54% [95% CI 49.1, 58.6]. Being divorced (AOR = 3.5; 95% CI 1.0, 12.2), having a lower level of knowledge (AOR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.0, 2.8), being on insulin (AOR = 6.3; 95% CI 1.9, 20.6), taking oral medication (AOR = 8.6; 95% CI 3.0, 24.5), being unaware of fasting blood sugar (AOR = 2.9; 95% CI 1.6, 5.2), not a member of a diabetic association (AOR = 3.6; 95% CI 1.7, 7.5), a lack of social support (AOR = 2.9; 95% CI 1.7, 4.9), and having a poor perceived benefit of self-care practices (AOR = 1.84; 95% CI 1.0, 3.2) were associated with poor self-care practices. Overall, this finding demonstrated that a significant percentage of participants (54%) had poor self-care practices. Being divorced, having a low level of knowledge about diabetes and fasting blood sugar, lacking social support, relying on oral medication, perceiving limited benefits from self-care practices, and not being a member of diabetic associations were identified as independent factors of poor self-care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder of multiple etiologies characterized by chronic hyperglycemia with disturbance of carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. It results from a defect in insulin secretion, defective insulin action, or both, which leads over time to serious damage to different organs1. According to the International Diabetics Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas 2019, there are an estimated 463 million (9.3%) people with diabetes aged 18–79, and the number of people to rise beyond 700 million in less than 25 years worldwide if not controlled. Of these people, 19.4 million adults live in Africa and Ethiopia is one of the members of IDF with 1.7 million people with diabetes2,3. Diabetes is a complex chronic illness that needs continuous medical care, in which one's self-care practice plays a significant role in the reduction of life-threatening conditions4,5.

Diabetes was known to be a disease in developed countries with rich people. Nevertheless, nowadays it has become a burden globally and specifically in developing countries6,7. Increased mortality and morbidity in developing and developed countries are caused by this incurable disease, and the lion's share is type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The IDF reported that in 2017, 4 million deaths occurred worldwide8,9, in contrast significantly higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) (1.3 million) deaths10. Diabetes is the 11th leading cause of infirmity worldwide; it is the major cause of new cases of blindness in adults; and it is also the leading cause of end-stage renal disease, accounting for about 20–40% of new cases. More than half of lower limb amputations occur among people with diabetes11,12. The economic burden of diabetes is significant across the globe, following the high proportion of deaths < 60 years, which is the workforce at 46.2% worldwide and the highest being Africa with 73.1%6,13,14.

Self-care is gradually acquiring skills and developing an understanding of the ways of living with diabetes15. Since the majority (95%) of self-care is done by the patient and their families, the patient's ability to practice self-care is the main component in keeping the disease under control and altering the outcomes. These practices include self-monitoring of blood glucose, nutrition, physical activity, monitoring of diabetic complications, and medication adherence15,16.

A lack of skills and appropriate knowledge of self-care practices worsens the burden of the disease each year15,17. It is confirmed that in lowering admissions and hospital visits, self-care has marked significance18. Diabetic self-care practices in Ethiopia range from 23.2 to 62.7%19,20. Evidence suggests self-care practice is a preferable approach with cost-effective and restorative results in countries like Ethiopia, where there are scant resources and ever-growing medical costs17,21.

As far as the researchers’ knowledge, the level of poor self-care practices and associated factors among people living with diabetes in Adama are not well understood. The present study involved both hospitals and primary healthcare facilities, but most prior studies were conducted in one of these settings. Moreover, factors associated with self-care practice were not well identified in Adama, Ethiopia. Therefore, the researcher aimed to assess the magnitude and associated factors of poor self-care practices in the study setting. The study will contribute to bridging the information gap and is expected to generate updated information.

Methods and materials

Study design, period, and population

An institutional-based cross-sectional study design was employed from April 01 to May 30, 2022, in Adama town, located 95 km from Addis Ababa. Adama town is one of Ethiopia's major cities, boasting a total population of 448,462, with 222,355 being male and 226,106 females. The town's healthcare infrastructure consists of one governmental hospital and eight health centers dedicated to providing follow-up care for diabetic patients. The hospital, situated within the town, offers preventive and curative services to over five million people. Additionally, the health centers collectively serve a catchment population of 410,64622.

The source population included all patients with T2DM who were receiving follow-up care at public health facilities in Adama town. The study population consisted of randomly selected T2DM patients who were undergoing diabetic follow-up at selected public health facilities in Adama town and had attended care during the study period. All type 2 adult diabetic patients (18 years and above) who had regular follow-ups for at least six months were included in the study. Adults with T2DM who were critically and mentally ill and pregnant women patients diagnosed during the study period were excluded.

Sampling size determination and sampling procedure

An independent sample size was calculated for the two specific objectives sought in the current study and the largest sample was taken to address both of the study’s aims. The largest sample size was the one calculated using the single population proportion formula which is used to estimate the magnitude of poor self-care practice among T2DM patients. The statistical assumptions for the calculation of sample size such as; a 95% desired level of confidence (95% CI) and a 5% margin of error were considered. Furthermore, the proportion of poor self-care practice (P) was considered to be 52% which was obtained from a similar study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia23. Accordingly, the calculated sample size becomes 384. Then, five percent of the calculated sample size was added to compensate for non-response. Consequently, the total sample size of 404 was considered to be incorporated in the current study.

Eight public health facilities in the town were stratified into hospitals and health centers. Using a simple random sampling technique, one hospital and two health centers were selected. The study participants were drawn from 683 patients in the hospital and 559 in the two health centers. Samples were allocated proportionally to each of the selected health facilities based on the expected number of patients attending care during the data collection period. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select study participants independently from each selected facility. The sampling interval at each facility 'ki' was determined by dividing the total number of attendants in one month (Ni) by the required sample size (ni) from each selected health facility i.e. ki = Ni /ni. Patients were selected every three intervals until the total sample size was reached. The random start among the first three attendants was determined using the lottery method.

Data collection tool

Data were collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire. The questionnaire contains information about socio-demographic factors (such as age, sex, educational status, marital status, occupation, income, residence, and religion), personal factors (including knowledge of diabetes, having a glucometer at home, membership in a diabetic association, social support, and diabetic counseling), clinical factors (such as having comorbidity, duration of diabetes, type of treatment, knowledge on of fasting blood sugar levels, and family history), diabetic health belief (covering perceived susceptibility to DM complications, perceived severity of DM, perceived benefits of self-care practices, and perceived barriers to self-care practices), treatment satisfaction (including the level of satisfaction with treatment and care) and Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) measure.

The self-care practice was measured by the SDSCA questionnaire, which was adopted from a validated SDSCA measure revised from seven studies' results24. This tool is commonly employed to evaluate various domains of diabetic self-care practices, including general and specific diet, exercise, medication adherence, self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), and foot care. It consists of 17 items with response choices ranging from 0 to 7, indicating the frequency of self-care activities performed in the last 7 days for each domain. Participants in the study who scored below the mean on the SDSCA were classified as having poor self-care practices, while those who scored at or above the mean were considered to have good self-care practices17,25.

The diabetic knowledge section comprises questions adapted from previously validated tools, specifically the revised brief diabetes knowledge test (DKT2)26. The DKT2 includes 14 general knowledge items suitable for adults with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, along with 9 items related to insulin use appropriate for adults with Type 1 diabetes. For our study, we focused solely on the general knowledge items. For our study, we focused solely on the general knowledge items. Due to their lack of relevance in the Ethiopian context and because they are not recommended for non-US patients, two items were omitted in the present study. Therefore, knowledge was measured using 12 general knowledge items, and each participant's score was calculated by dividing the number of correct answers by the total number of questions. Participants who scored at or above the overall mean value were considered to have adequate knowledge27.

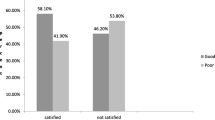

The diabetic treatment satisfaction questionnaire (DTSQ) consisted of six items assessing treatment satisfaction, each was scored on a scale of 1–5, with five representing the greatest satisfaction28. A five-point Likert scale (1) very unsatisfied, (2) unsatisfied, (3) neutral, (4) satisfied, and (5) very satisfied) was used to grade the level of satisfaction of patients. The diabetic health belief was assessed by adapting 16 item questionnaire, as developed by Given29, on perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers, to measure the beliefs of diabetic patients about their diabetes which had proven to be reliable in a similar study in Nigeria30. Agreement with each item on diabetic health belief was indicated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The questionnaire was first translated from English to local languages (Amharic and Afaan Oromoo) and then translated back to English to ensure consistency and accuracy. Data collection was conducted by four trained BSc nurses from different facilities, alongside two supervisors. A pre-test involving 5% of the total sample of patients at non-selected public health institutions was carried out to ensure the quality and compliance of the data abstraction format and questionnaire with the study’s objectives., and a correction was made accordingly. Data collectors and supervisors were given two days of training on data collection procedures and the goal of the study. All collected data were validated for completeness and consistency during data management, storage, and analysis.

Data processing and analysis

Data were coded and entered into a computer using Epi-Info Version 7.2 and exported to SPSS version 25 statistical software for processing and analysis. Before analysis data cleaning, coding, and categorizing were performed. Before choosing the appropriate numerical summary measures for continuous variables, normality was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and explore the characteristics of patients. The level of poor self-care practices was estimated using proportion along with 95% CI.

The associations between independent variables and self-care practices were modeled using binary logistic regression analysis. The statistical assumptions for binary logistic regression (adequacy of sample in each cross-tabulated result, expected count in each cell) were assessed before fitting the regression model. First simple logistic regression analysis was used to select variables that had a crude association with self-care practice. At this level, the candidate independent variables for multiple regression analysis were selected at P-value < 0.25. Multiple logistic regression was applied to identify independent variables significantly associated with self-care practices after adjusting for the effects of possible confounding variables.

The regression model was fitted using a standard model-building approach. The procedure of fitting the model started with subjecting all selected variables to multiple regression, and in the process variables that did not have a significant association with poor self-care practice at a p-value < 0.05 were excluded from the model one by one starting with variables with the worst P-value. The odds of having poor self-care practice were estimated using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% CI. The significance of associations was declared for variables with a p-value less than 0.05. The final fitted model was assessed for multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of 10 and goodness of fit using the Hosmer and Lemeshow test.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Adama Hospital Medical College Institutional Review Board (IRB) with Reference number 0911/k373/14 and permission to conduct the study was secured from respective health facilities. The study was employed following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed consent and confidentiality was maintained by using codes without personal identifiers.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

In this study, a total of 387 diabetic patients on follow-up care were included giving a response rate of 95.8%. The median (± Interquartile range) age of study participants was 58 (48–65) years. Among diabetic patients, 198 (51.2%) were females and 299 (77.3%) were married (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics

Among participants, 120 (31%) had a family history of diabetes, 142 (36.7%) had diabetic-related complications, of which 112 (78.9%) had hypertension. Regarding the type of medications, 272 (70.3%) were taking oral medication. Among participating patients, 240 (62.0%) were aware of their FBS status of which 200 (83.3%) of them had FBS levels of 130 mg/dl and above (Table 2).

Personal factors

The study revealed that 160 (41.3%) patients were diagnosed with DM five years back. Among patients, 203 (52.5%) have been receiving diabetic counseling, and 309 (79.8%) were not a member of the diabetic association. Among the participants, 231 (59.7%) had a lower level of knowledge regarding DM, and 201 (51.9%) had infrequent social support (Table 3).

Diabetic health belief

The result of this study revealed that 222 (57.4%) and 218 (56.3%) patients responded with unfavorable perceived severity and perceived benefit of self-care practices respectively (Table 4).

Diabetic self-care practices

This study indicated that the magnitude of poor self-care practices was 54% [95% CI 49.1, 58.6]. In stratified analysis, the magnitude of poor self-care practices was 218 (56.3%) on diet, 191 (49.4%) on physical activity, 158 (40.8) on SMBG, and 195 (50.4%) on foot care among respondents.

Factors associated with self-care practices

From the simple logistic regression analysis, monthly income, marital status, diabetic counseling, having a family history of diabetes, types of current treatment, having a glucometer, being aware of recent FBS, level of knowledge on diabetes, membership of the diabetic association, having social support, perceived susceptibility of DM complication, the perceived barrier of self-care practice, perceived severity of DM, and perceived benefit of self-care practice were selected as a candidate variables for multiple regression at a p-value of < 0.25. After adjusting for possible confounders, marital status, types of current treatment, being aware of recent FBS, level of knowledge on diabetes, being a member of the diabetic association, having social support, and perceived benefit of self-care practices showed statistically significant association with poor self-care practices.

Accordingly, divorced patients had 3.5 higher odds of poor self-care practices compared to widowed patients (AOR = 3.5; 95% CI 1.05, 12.25). It was also identified that patients who were on insulin injections alone had 6.3 times (AOR = 6.3; 95% CI 1.98, 20.64) and those who were on oral medications had 8.6 times (AOR = 8.6; 95% CI 3.03, 24.5) higher odds of poor self-care practices compared to those who were taking both insulin injection and oral medications. Furthermore, 2.9 times higher odds of poor self-care practices were documented among diabetic patients who were unaware of their recent FBS compared to those who were aware of the current FBS (AOR = 2.9; 95% CI 1.68, 5.2). Diabetic patients who had a lower level of knowledge of DM had 70% (AOR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.01, 2.86) increased odds of poor self-care practices compared to those with a higher level of knowledge.

Moreover, patients who were not members of the diabetic association had 3.6 (AOR = 3.6; 95% CI 1.70, 7.59) higher odds of poor self-care practices compared to those who were members of the association. The odds of having poor self-care practice among patients having infrequent social support were 2.9 times (AOR = 2.9; 95% CI 1.78, 4.94) higher compared to those who have frequent social support. The odds of having poor self-care practices among patients who had an unfavorable perceived benefit of self-care practices were 84% higher compared to those who had a favorable perceived benefit of self-care practices (AOR = 1.84; 95% CI 1.04, 3.24) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the level of poor self-care practices and contributing factors among adults with type 2 diabetes in Adama, Ethiopia. The study revealed an overall level of poor self-care practice of 54% [95% CI 49.1, 58.6]. The finding is consistent with studies conducted in Addis Ababa (52%)23, Gondar (51.86%)31, and Tigray (53.3%)3, but it is higher than the study done in the UAE (15.3%)16, Iran (26.2%)32, and other studies in Ethiopia (Dilla (23.2%)20, West Oromia (36.4%)21, Diredawa (44.1%)27, and Nekemte (45%)14. On the other hand, it is lower than the studies' findings in Bahirdar (71.6%)33 and Mekelle (62.7%)19. The inconsistencies might be due to differences in the cultural and socioeconomic characteristics of the Ethiopian community, as well as the diverse lifestyles within Ethiopia. Additionally, improvements in the healthcare systems over time may have contributed to these inconsistencies. Prior studies assessed self-care practices only over the previous three days, which might have made it difficult to accurately analyze patients' self-care behaviors. In contrast, the current study assessed self-care practices over the last seven days, providing a longer period to capture the frequency of self-care activities. Furthermore, this study measured the number of days individuals practiced self-care, whereas previous studies used simple 'Yes' or 'No' questions to assess self-care practices3,27,31. Furthermore, because of the large number of patients in the facilities, waiting times may deter patients from getting the information they require about self-care techniques.

This study revealed statistically significant positive associations between patients who were divorced and poor self-care practices. This result is consistent with studies conducted in Felegehiwot34 and Gondar35, but contrasts with findings from Addis Ababa36 and West Oromia21, where married patients were associated with poor self-care practices. The possible reason could be that divorced patients may lack emotional support from loved ones, making it more difficult for them to cope with various problems and focus on diabetic self-care practices33.

According to this study, a lower level of knowledge about diabetes and its complications showed increased odds of poor self-care practices. The finding is in line with a study done in western Ethiopia17. This can be explained by the fact that less knowledgeable patients may not be conscious of the benefits of self-care practices and prevention regarding the long-term complications of DM 27,37. One argument is that having the correct knowledge about DM and self-care practices promotes clarity and minimizes confusion regarding the practice and the medical condition27.

In this study, patients who were on oral medication had higher odds of poor diabetes self-care practices as compared to patients who were on insulin and oral medications. Furthermore, patients who were taking only insulin injections had higher odds of poor self-care practices as compared to those who took both insulin and oral medication. The associations between types of medications and diabetic self-care practices are inconsistent. A study in Iran indicated insulin injection was significantly associated with good self-care practice32, while a study done in Bahir Dar town in Ethiopia reported contrasting results33. One reason could be that these individuals may have DM that is not controlled by monotherapy (tablets or insulin alone). Moreover, patients who take a single medication may have had diabetes for a shorter duration than those who are on both insulin and oral therapies. Therefore, they might be more concerned about medication side effects than the long-term complications of DM due to their limited knowledge and experience compared to those with a longer duration of diabetes38,39.

This study showed that DM patients who did not know their fasting glucose level had greater odds of poor self-care practices as compared to their counterparts. This is in line with a study conducted in Tigray, Ethiopia19. Potential explanations include the possibility that individuals unaware of their blood glucose level may not feel motivated to engage in necessary self-care activities, such as eating a healthy diet, exercising, reducing risk, and following recommended self-care guidelines19,40.

In this study, the absence of membership in the diabetic association was another important variable statistically associated with poor self-care practices. The finding is in agreement with a study in Ethiopia, which reported higher odds of poor self-care practices among DM patients who were not members of DM associations34. The lack of regular monthly diabetic education and support provided to patients, such as access to medication for some lower-income members and relatively inexpensive blood glucose testing, could explain this association. Additionally, patients who are not members of the diabetic association may miss out on receiving support and exchanging beneficial experiences41.

The lack of social support was found to be significantly associated with poor self-care practices. Similar findings were observed in studies conducted in Anand Gujarat India4, Addis Ababa23, and West Shoa Oromia42. Social support, whether in the form of emotional, financial, or informational assistance from family or friends, can provide patients with the psychological resilience needed to cope with the complexities of managing diabetes. There is a pressing need for a more supportive environment, as effective social support may facilitate behavioral adjustments leading to improved self-care practices3,27,31,43. Therefore, DM patients who lack adequate social support may struggle to implement essential changes in their physical and dietary habits.

Finally, an unfavorable attitude towards the perceived benefits of self-care practices was significantly associated with poor self-care practices. This finding aligns with studies conducted in Northern Ethiopia19 and Nigeria30. This is sensible because a negative attitude towards self-care weakens beliefs about the expected benefits and healthy behaviors44. Moreover, these findings could be attributed to a lack of formal diabetes education, which can influence attitudes toward diabetic self-care behaviors19,45,46.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study's strength lies in its collection of primary data from multiple care centers, providing a more representative sample. However, it has certain limitations. Firstly, being a cross-sectional study, it cannot demonstrate causal relationships between variables. Secondly, Second, because the study asks about patients' self-care activities during the past seven days and is based on self-reports, the performance of their behaviors was not observed and could not be confirmed. Additionally, since data was collected through interviewer-administered methods by healthcare providers, responses may be influenced by social desirability biases.

Conclusion

The study revealed that a significant proportion of type 2 diabetes patients had poor diabetes self-care practices, although these practices are essential for controlling diabetes and preventing its complications. Being divorced, having a low level of knowledge about diabetes and fasting blood sugar, lacking social support, relying on oral medication, perceiving limited benefits from self-care practices, and not being a member of diabetic associations were identified as independent factors contributing to poor self-care.

Recommendations

Healthcare providers should focus on patients who exhibit the aforementioned characteristics. Plans should also be developed to support diabetic individuals in practicing greater self-care. The Ethiopian Diabetes Association needs to advocate for the benefits of membership as well as advise and empower patients to adhere to the recommended diabetes self-care practices. It is recommended that patients join nearby diabetic associations to be able to receive support, affection, and help. Family members should be informed about their important roles in encouraging patients to adopt recommended self-care practices. Future studies should investigate barriers to self-care practices using a qualitative study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to participant data protection regulations but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- COR:

-

Crudes odds ratio

- DKT:

-

Diabetic knowledge test

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DTSQ:

-

Diabetic Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood sugar

- IDF:

-

International Diabetic Federation

- SDSCA:

-

Summary of self-care activities

- SMBG:

-

Self-monitoring of blood glucose

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social science

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

References

Organization, W. H. Classification of Diabetes Mellitus (World Health Organization, 2019).

Saeedi, P. et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107843 (2019).

Molalign Takele, G. et al. Diabetes self-care practice and associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients in public hospitals of Tigray regional state, Ethiopia: A multicenter study. PLoS One 16(4), e0250462 (2021).

Raithatha, S. J., Shankar, S. U. & Dinesh, K. Self-care practices among diabetic patients in Anand district of Gujarat. Int. Sch. Res. Not. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/743791 (2014).

Dedefo, M. G. et al. Self-care practices regarding diabetes among diabetic patients in West Ethiopia. BMC. Res. Notes 12(1), 1–7 (2019).

Saeedi, P. et al. Mortality attributable to diabetes in 20–79 years old adults, 2019 estimates: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 162, 108086 (2020).

Whiting, D. R. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 94(3), 311–321 (2011).

Cho, N. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 271–281 (2018).

Nanayakkara, N. et al. Impact of age at type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis on mortality and vascular complications: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia 64(2), 275–287 (2021).

Lin, X. et al. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–11 (2020).

Dedefo, M. G. et al. Predictors of poor glycemic control and level of glycemic control among diabetic patients in west Ethiopia. Ann. Med. Surg. 55, 238–243 (2020).

Zheng, Y., Ley, S. H. & Hu, F. B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14(2), 88–98 (2018).

Bommer, C. et al. The global economic burden of diabetes in adults aged 20–79 years: A cost-of-illness study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5(6), 423–430 (2017).

Amente, T. et al. Self care practice and its predictors among adults with diabetes mellitus on follow up at Nekemte hospital diabetic clinic, West Ethiopia. World J. Med. Med. Sci. 2(3), 1–16 (2014).

Shrivastava, S. R., Shrivastava, P. S. & Ramasamy, J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 12(1), 1–5 (2013).

Al-Maskari, F. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of diabetic patients in the United Arab Emirates. PLoS One 8(1), e52857 (2013).

Chali, S. W., Salih, M. H. & Abate, A. T. Self-care practice and associated factors among Diabetes Mellitus patients on follow up in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State Public Hospitals, Western Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC. Res. Notes 11(1), 1–8 (2018).

Jackson, I. L. et al. Knowledge of self-care among type 2 diabetes patients in two states of Nigeria. Pharm. Pract. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1886-36552014000300001 (2014).

Mariye, T. et al. Magnitude of diabetes self-care practice and associated factors among type two adult diabetic patients following at public Hospitals in central zone, Tigray Region, Ethiopia, 2017. BMC. Res. Notes 11(1), 1–6 (2018).

Addisu, Y., Eshete, A. & Hailu, E. Assessment of diabetic patient perception on diabetic disease and self-care practice in Dilla University Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia. J. Metab. Synd. 3(166), 2167–0943 (2014).

Diriba, D. C., Bekuma, T. T. & Bobo, F. T. Predictors of self-management practices among diabetic patients attending hospitals in western Oromia, Ethiopia. PLoS One 15(5), e0232524 (2020).

Mekuria Negussie, Y. & Tilahun Bekele, N. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy among adult type 2 diabetes patients in Adama, Ethiopia: Health facility-based study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 3844 (2024).

Wolderufael, M. & Dereje, N. Self-care practice and associated factors among people living with type 2 diabetes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A facility-based cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 14, 1 (2021).

Toobert, D. J., Hampson, S. E. & Glasgow, R. E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 23(7), 943–950 (2000).

Kassa, R. N. et al. Self-care practice and its predictors among adults with diabetes mellitus on follow up at public hospitals of Arsi zone, southeast Ethiopia. BMC. Res. Notes 14(1), 1–6 (2021).

Fitzgerald, J. T. et al. Validation of the revised brief diabetes knowledge test (DKT2). Diabetes Educ. 42(2), 178–187 (2016).

Getie, A. et al. Self-care practices and associated factors among adult diabetic patients in public hospitals of Dire Dawa administration, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 20(1), 1–8 (2020).

Bradley, C. et al. The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire change version (DTSQc) evaluated in insulin glargine trials shows greater responsiveness to improvements than the original DTSQ. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 5(1), 1–12 (2007).

Given, C. W. et al. Development of scales to measure beliefs of diabetic patients. Res. Nurs. Health 6(3), 127–141 (1983).

Adejoh, S. O. Diabetes knowledge, health belief, and diabetes management among the Igala, Nigeria. Sage Open 4(2), 2158244014539966 (2014).

Aschalew, A. Y. et al. Self-care practice and associated factors among patients with diabetes mellitus on follow up at University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 12(1), 1–6 (2019).

Yekta, Z., et al., Assessment of Self-Care Practice and its Associated Factors Among Diabetic Patients in Urban Area of Urmia, Northwest of Iran (2011).

Abate, T. W., Tareke, M. & Tirfie, M. Self-care practices and associated factors among diabetes patients attending the outpatient department in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 11(1), 1–5 (2018).

Feleke, S. A. et al. Assessment of the level and associated factors with knowledge and practice of diabetes mellitus among diabetic patients attending at FelegeHiwot hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin. Med. Res. 2(6), 110 (2013).

Asmelash, D. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards glycemic control and its associated factors among diabetes mellitus patients. J. Diabetes Res. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2593684 (2019).

Berhe, K. K. et al. Diabetes self care practices and associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients in Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia-a cross sectional study. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 3(11), 4219 (2012).

Tiruneh, S. A. et al. Factors influencing diabetes self-care practice among type 2 diabetes patients attending diabetic care follow up at an Ethiopian General Hospital, 2018. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 18, 199–206 (2019).

Ahmann, A. Combination therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Adding empagliflozin to basal insulin. Drugs Context https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.212288 (2015).

Fried, T. R. et al. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62(12), 2261–2272 (2014).

Association, A. D. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 43, S48–S65 (2020).

Addis, S. G. et al. Self-care practice and associated factors among type 2 adult diabetic patients on follow up clinic of Dessie referral hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. Clin. J. Nurs. Care Pract. 5(1), 031–037 (2021).

Gurmu, Y., Gela, D. & Aga, F. Factors associated with self-care practice among adult diabetes patients in West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18(1), 1–8 (2018).

Abate, T. W., Tareke, M. & Tirfie, M. Self-care practices and associated factors among diabetes patients attending the outpatient department in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 11, 1–5 (2018).

Educators, A.A.O.D., AADE 7™ self-care behaviors: American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) position statement. Available in https://www.diabeteseducator. org/docs/default-source/legacydocs/_resources/pdf/publications/aade7_position_statement_final. pdf, 2014.

Letta, S. et al. Self-care practices and correlates among patients with type 2 diabetes in Eastern Ethiopia: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 10, 20503121221107336 (2022).

Alodhayani, A. et al. Association between self-care management practices and glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saud Arabia: A cross–sectional study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28(4), 2460–2465 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank health facilities for their enormous help in providing important information and facilitating every activity during data collection. We are very grateful to the data collectors and participants who were very cooperative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.T.B. contributed to the study conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and drafting of the first version of the manuscript. N.T.B. and Y.M.N. critically reviewed the drafted manuscript and wrote the final version. H.A.D. and E.M.H. advised on the study design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, and the final version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekele, N.T., Habtewold, E.M., Deybasso, H.A. et al. Poor self-care practices and contributing factors among adults with type 2 diabetes in Adama, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 14, 13660 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63524-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63524-8

- Springer Nature Limited