Abstract

Cancer patients experience psychological symptoms such as depression during the cancer treatment period, which increases the burden of symptoms. Depression severity can be assessed using the beck depression inventory (BDI II). The purpose of the study was to use BDI-II scores to measure depression symptoms in cancer patients at a large tertiary hospital in Palestine. A convenience sample of 271 cancer patients was used for a cross-sectional survey. There are descriptions of demographic, clinical, and lifestyle aspects. In addition, the BDI-II is a tool for determining the severity of depression. Two hundred seventy-one patients participated in the survey, for a 95% response rate. Patients ranged in age from 18 to 84 years, with an average age of 47 years. The male-to-female ratio was approximately 1:1, and 59.4% of the patients were outpatients, 153 (56.5%) of whom had hematologic malignancies. Most cancer patients (n = 104, 38.4%) had minimal depression, while 22.5%, 22.1%, and 17.0% had mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. Education level, economic status, smoking status, and age were significantly associated with depression. The BDI-II is a useful instrument for monitoring depressive symptoms. The findings support the practice of routinely testing cancer patients for depressive symptoms as part of standard care and referring patients who are at a higher risk of developing psychological morbidity to specialists for treatment as needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality both worldwide and in Palestine, accounting for 14% of all deaths, after heart disease (30%)1,2. Additionally, the anticipated rise in cancer diagnoses among Palestinians is likely to place added strain on the already stretched financial and infrastructural resources of the healthcare system, particularly given the prevailing financial and political uncertainties2,3,4,5. As advancements in cancer treatments progress, more patients are experiencing either complete cures or extended life expectancies. As a result, there is increased focus on the emotional challenges that come with being diagnosed with and treated for cancer. Research indicates that approximately 30% of patients experience mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders6, although the exact prevalence varies depending on the specific condition7. Treating depression can lead to better emotional and psychological health, even amidst the physical toll of cancer symptoms. Mood plays a significant role in how patients perceive their quality of life (QoL) and the extent of their suffering. It can begin at the time of diagnosis and continue beyond the completion of cancer treatment8.

Depression is associated with decreased functional status, decreased adherence to treatment, longer hospitalizations, and the desire to die sooner9. Almost 25% of cancer patients experience severe depressive symptoms, whereas 77% of those with advanced disease experience severe depressive symptoms10. Depression is common in cancer patients and is strongly associated with oropharyngeal (22–57%), pancreatic (33 to 50%), breast (1.5–46%), and lung (11 to 44%) cancer. Patients with other malignancies, such as colon (13–25%), gynecological (12–23%), and lymphoma (8–19%), had a lower frequency of depression7.

Depressive symptoms are often identical to those of physical illness or its treatments, making it difficult to diagnose depression in physically ill people. This is especially true when a cancer patient is diagnosed with depression. Many of the symptoms needed to diagnose depression are often caused by cancer treatments (e.g. chemotherapy, biological therapy), such as fatigue, weight loss, anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure in typically enjoyable activities) and psychomotor retardation.

Depression, also known as clinical depression or severe depressive disorder, is a prevalent yet serious mood disorder. It manifests as severe symptoms that impact a person's emotions, thoughts, and ability to cope with daily activities such as sleeping, eating, and working. These symptoms must persist for at least two weeks to be diagnosed7.

Various techniques have been created to evaluate how well symptoms are managed, aiding in the recognition of linked symptoms. For instance, the beck depression inventory (BDI II)-21 is capable of evaluating prevalent psychological symptoms among cancer patients. The BDI-II remains instrumental in exploring the characteristics and evaluation of depression. Its effectiveness as a screening tool in patients with medical conditions and cancer has been examined in multiple research studies, establishing it as a reliable self-reported assessment tool11.

Cancer patients suffer many symptoms during cancer progression that negatively affect their QoL. Importantly, there is no comforting care assessment tool, such as the BDI, available for cancer patients in Palestine. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate cancer patients’ reported depression symptoms using the beck depression scale (BDS) at a large tertiary care hospital. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study assessing depression using the BDI-II in occupied Palestinian territories in the context of mental health.

Methods

Study design

The research objectives were pursued through a quantitative cross-sectional investigation.

Study setting

An-Najah National University Hospital (NNUH) was established in 2013 through a partnership with the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. NNUH stands as Palestine's sole facility, offering sophisticated electrophysiology, intricate open-heart surgeries, autologous bone marrow transplants, and specialized care for both adult and pediatric leukemia patients. NNUH encompasses various medical units, an emergency ward, dialysis facilities, radiology services, and ultrasound and tomography departments and has a capacity of 120 beds12.

Study population

Cancer patients receive comprehensive care through outpatient oncology clinics and inpatient services at NNUH. These services cover various procedures, including diagnosis, chemotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation (autoBMT), and the management of treatment side effects or complications. In certain oncological scenarios, such as neutropenic fever, patients may require immediate attention, leading to visits to the emergency room followed by hospital admission. This integrated approach ensures that patients receive comprehensive and timely care for their cancer treatment needs at NNUH.

Sample size

During the research period spanning from April 2021 to August 2021, the NNUH received an average of 600 cancer patients each month. This number served as the basis for determining the necessary sample size for analysis. Using the Raosoft sample size calculator with a response distribution of 0.50, an error margin of 5%, and a confidence interval of 95%, a preliminary sample size of 235 was calculated. However, to accommodate potential dropout rates, this figure was adjusted, indicating a requirement of 259 patients. To bolster the study's robustness and mitigate the risk of erroneous results, an additional 10% of the sample (24 patients) was included, bringing the final targeted sample size to 285. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were evaluated through content validity, construct validity, and reliability testing methods. Hence, we only used triangulation, involving two hemato-oncology physicians, three oncology nurses, and one statistician, to verify the validity of the data. We also assessed the consistency of 11 patients (22 questionnaires) between their two visits. Moreover, after creating the questionnaire, we piloted it on 11 patients, making adjustments as necessary based on their feedback.

Sampling procedure

The researchers utilized convenience sampling, involving 271 cancer patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Ensuring that patients agree to participate is vital for ethical research.

-

The ability to read and write at age 18 ensures that patients can understand the study information and provide feedback.

-

Specifying cancer and hematologic malignancies keeps the study focused on the relevant patient population. Both inpatients and outpatients are included to capture a broader range of experiences.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients in the ICU may be too critically ill to participate effectively.

-

Patients in a coma were unable to consent or participate in the study.

-

Patients with preexisting cognitive issues may not be able to understand or participate in the study reliably.

-

Isolated patients may have difficulty communicating or require special protocols that the study may not be equipped for.

Data collection instrument

Patients completed the questionnaires themselves, and nurses explained the questions if patients requested further clarification. All surveys were performed on paper and then analyzed using an electronic database. This study involved a secondary analysis of previously published data using various approaches in another study on factors related to palliative care symptoms in cancer patients in Palestine13. The data included patient demographics and clinical characteristics collected at various points during cancer treatment, such as diagnosis, chemotherapy, clinic visits, AutoBMT, advanced cancer stages, outpatient and inpatient oncology visits, and related factors. The data were collected over 5 months, from April to August 2021. Patients were provided with the Arabic version of the BDI-II14 by either the researcher or a designated nurse and were encouraged to fill it out themselves, with assistance available if needed.

The surveys were kept in a designated location within particular departments designed for adult patients with cancer. These departments included outpatient oncology clinics, medical oncology units, vascular units, surgical units, bone marrow transplant and leukemia units, and surgical cardiac care units. Furthermore, the researcher gathered additional medical data from the patients' records. Approximately 15 patients chose not to participate, and 10 surveys were unfinished. Assessment tools for psychological symptoms, such as the BDI-II, provide a baseline assessment and evaluation for depression in cancer patients.

Beck depression inventory (BDI) II

Many factors contribute to the variation in depression incidence, including patient age and sex, medical status, cancer diagnosis, and cancer stage15. Hence, these inquiries also aid in evaluating depression among individuals with cancer. Moreover, questions regarding the diagnostic approach (such as inclusion or substitution methods), the type of assessment utilized (including diagnostic interviews or self-reported measures), and the criteria for inclusion (whether clinical or subclinical) are crucial for assessing depression within this demographic group.

The BDI, short for Beck Depression Inventory, is a tool consisting of 21-point self-assessment ratings designed to gauge attitudes and symptoms of depression. Completing the BDI typically takes approximately 10 min, yet individuals are required to possess a reading level equivalent to fifth or sixth grade to comprehend the questionnaire adequately. Clinicians employ this inventory to ascertain the severity of depression in individuals and tailor appropriate therapeutic interventions. The BDI was developed by Aaron T. Beck, a prominent psychiatrist recognized as the pioneer of cognitive behavior therapy16.

Depression is a medical condition characterized by a prolonged feeling of sadness. This leads to a lack of interest in previously enjoyable activities and can greatly disrupt daily life. While experiencing sadness is normal in response to events such as the loss of a loved one, financial strain, relationship issues, or job loss, clinical depression occurs when these feelings persist for an extended period without an obvious cause16.

Questions on the BDI-II

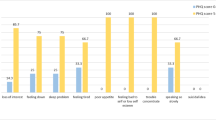

The BDI-II comprises 21 inquiries aligned with the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-V, which professionals use to assess mental health conditions. Each question offers multiple-choice responses with scores ranging from 0 to 3. These questions address various aspects, such as feelings of sadness, pessimism, past failures, loss of pleasure, guilt, self-criticism, suicidal thoughts, agitation, changes in sleeping and eating patterns, concentration difficulties, fatigue, and diminished interest in activities once enjoyed.

Scores on the BDI-II

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) utilizes a straightforward scoring method in which each of the four multiple-choice options is given a score ranging from 0 to 3. After all 21 questions are answered, the total points are tallied. Based on the total score, the severity of depression was categorized as follows: no depression (0–13 points), mild depression (14–19 points), moderate depression (20–28 points), or severe depression (29–63 points)16.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Social Sciences Statistical Package (SPSS) version 21. Basic demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. When comparing continuous variables provided as the median and interquartile range, Mann‒Whitney U/Kruskal‒Wallis tests were used. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of An-Najah National University and the NNUH administrator approved this study. All methods used in the study were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Helsinki Declaration. Participants signed an informed consent form guaranteeing data privacy, and all the data were kept confidential and used exclusively for research purposes.

Results

Demographic data

The study included 271 participants, for a response rate of 95%. Table 1 shows the distribution of cancer types among our sample. Among them, 52% were younger than 50 years, and the majority (67.9%, n = 184) were married. The average age was 47.17 years, ranging from 18 to 84 years. The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 51.3% men and 48.7% women. In terms of education, the majority (67.5%, n = 183) had completed high school, while 32.5% (n = 88) had completed university or college. Regarding socioeconomic status, 53.9% had a low income (< 2000 NIS), 38.4% had a middle income (2000–5000 NIS), and only 7.7% had a high income (> 5000 NIS).

Among all participants, 22.1% were smokers, 4.8% had deformities such as Tal Hashomer syndrome, 36.5% were employed, 47.6% lived in villages, and 41.0% resided in cities. Furthermore, 59.4% were outpatients, and 56.5% were diagnosed with hematologic malignancies. Notably, the majority of cancer patients (88.9%, n = 241) were receiving treatment, with 75.6% actively receiving chemotherapy. Family psychological support was the most common form of support (59.8%), followed by support from healthcare teams (44.3%), religious support (38.0%), and social support (34.3%) (see Table 2).

The severity among cancer patients according to the BDI-II

The majority of cancer patients (38.4%) had minimal depression, while 22.5%, 22.1%, and 17.0% had mild, moderate, or severe depression, respectively (see Table 3). However, the median BDI score [Q1-Q3] was 17.0 [10.0–24.0], and the mean ± SD was 18.2 ± 11.0.

The associations between patient characteristics and depression are shown in Table 2. The results showed that cancer patients over 50 years of age had significantly more depression than those younger than 50 years of age did (p = 0.024), and the median BDI score was 18.5 [11.0–25.0] for the > 50 years age group and 15.0 [9.0–24.0] for the > 50 years age group. A significant difference was also found in the categories of educational level (p < 0.001), where cancer patients with low educational levels had higher depression scores than those with higher educational levels (university or college). Furthermore, poor socioeconomic status was significantly associated with increased depression intensity. The current study showed that smokers had moderate depression, as indicated by a BDI-II score of 20.0 [13.0–29.0], while nonsmokers had mild depression, with a BDI-II score of 16.0 [10.0–24.0]. This difference was significant (p = 0.004). Other factors, such as sex, social status, type of cancer, hospitalization status, and psychological support, were not significantly associated with the BDI-II score.

Discussion

Cancer patients receiving treatment at NNUH visit outpatient oncology clinics or are admitted as inpatients for various purposes, including diagnosis, chemotherapy sessions, autologous bone marrow transplants, and managing side effects or complications of treatment. These services cater to patients with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies such as leukemia, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma. Some oncological conditions, such as neutropenic fever, require referral to the emergency room followed by admission to the hospital.

In our research group, we observed an equal distribution between males and females, approximately 1:1, mirroring the broader pattern of cancer cases in Palestine. According to data from the Palestinian Ministry of Health in 202017, nearly half of all cancer patients were male (49.3%), with slightly more females (50.7%). Conversely, a study conducted in Italy demonstrated a greater proportion of female participants, accounting for 58% of the sample18.

In our research, the average age of the individuals involved was 47 years, whereas in previous studies, the average ages ranged from 49.12 years19 to 61.9 years18. In our study, 88.9% of the individuals diagnosed with cancer received treatment, while the remainder were in the diagnostic phase. This proportion closely resembles that found in an earlier study, which also focused on patients undergoing chemotherapy, where 82% were in the treatment stage18.

In Palestine, depression represents approximately 15.3% of mental disorders20. In this study, 38.4% of cancer patients had minimal depression, 22.5% had mild depression, 22.1% had moderate depression, and 17.0% had severe depression based on the BDI-II scale. On the other hand, a study conducted in Gaza Strip, Palestine, used the same scale (BDI) and reported that 7.7% of cancer patients were minimally depressed, 15% were mildly depressed, 53.4% were moderately depressed, and 24.2% were severely depressed. Another study used a different scale (the center for epidemiological studies depression scale, CES-D) and reported that 44% of Palestinian cancer patients had severe depression21. In another population group in Palestine, 33.9% of hemodialysis patients were moderately depressed, and 29% had severe depression22.

The elevated rate of depression in Palestine could be linked to major stress factors such as the enduring siege and occupation23, heightened anxiety levels24, and challenges in obtaining healthcare services25.

In comparison to research conducted in other regions, various studies have examined the prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients. In Jordan, 52.7% of respondents experienced minimal depression, 26.0% displayed mild symptoms, 19.5% exhibited moderate symptoms, and 1.8% had severe symptoms19. Similarly, in Turkey, 52.0% of breast cancer patients scored 17 or higher on the BDI scale26. Another study employed the hospital anxiety depression scale (HADS) to assess depression among cancer patients, revealing prevalence rates of 23.1% for mild depression, 11.1% for moderate depression, and 2.3% for severe depression27. A cross-sectional investigation in Milan, Italy, utilizing the HADS reported that 4.1% of cancer patients experienced severe depression18. Moreover, a study in Greece using the Greek translation of the BDI-21 revealed that 69.5% of respondents scored above 10 (indicating mild depression), 39% scored above 16 (indicating moderate to severe depression), and 11.4% scored above 30 (indicating severe depression). Notably, women were more prone to depression than men, with a significant portion experiencing mild to severe depression28. Unfortunately, there is a lack of specialized centers in Palestine that are crucial for mitigating depression symptoms in cancer patients29.

In the current study, we found that depression was more prevalent in cancer patients aged > 50 years. As previously demonstrated in a study using the HADS for breast cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy in Palestine, age older than 51 years was associated with a greater risk of depression30. A cross-sectional study conducted in two Jordanian hospitals concluded that age was not significantly associated with BDI-II scores19.

Regarding educational level, we found that cancer patients with low educational levels had more depression, which is similar to the findings of other studies31,32. However, other publications did not show a significant difference between the two variables of education level and depression19,33. Depression was also associated with socioeconomic status since patients with poor socioeconomic status had more depression. However, compared to other studies, depression was not significantly associated with socioeconomic status19,32.

Our findings revealed that smoking cancer patients had greater depression scores than nonsmokers. Smoking habits may develop through stressful life events. For example, in Palestine, many people complain of psychological problems resulting from traumatic events from the Israeli occupation20,24,34 and anxiety24,25. Smokers account for more than one-fifth of people aged 18 and over; according to the Palestinian Household Survey conducted by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) in 2010, 22.5% of Palestinians aged 18 and over in the Palestinian territory are smokers (26.7% in the West Bank compared to 14.6% in the Gaza Strip). The Jenin Governorate had the highest percentage of smokers (32.2%), while the North Gaza Governorate had the lowest percentage (11.3%)35. Smoking is also common in cancer patients36. Additionally, other studies have corroborated reports of diminished well-being among smokers37,38. The findings of the current study revealed that psychosocial assistance was not associated with lower depression scores; however, these findings contradict previous research that suggested that cancer patients should take advantage of accessible psychological support services to reduce their depression and that cancer patients should take advantage of available psychological support services to reduce their depression39,40.

Additionally, the analysis of depression levels revealed a significant link between socioeconomic status and smoking habits, consistent with prior research41,42,43,44. Furthermore, there was a correlation between anxiety levels and educational attainment among cancer patients. Those with lower education levels reported higher anxiety scores, while those with higher education levels showed lower scores, indicating a potential protective effect of higher education on long-term anxiety and sadness45. Our study also revealed that anxiety levels were greater in cancer patients at the diagnosis stage than in those undergoing treatment, in line with previous research that identified chronic inflammatory conditions as risk factors for anxiety and depression in cancer patients, particularly during the diagnostic phase46.

The 4.8% prevalence of deformities reported in our study encompasses various types of deformities, including tal Hashomer syndrome. However, due to the rarity of Tal Hashomer syndrome, its specific prevalence within our study population is also very low. The literature has noted infrequent instances of Tel Hashomer syndrome and Guillain‒Barré syndrome among lymphoma patients47.

The scales utilized in our research possess several advantages. First, by assessing ten symptoms, they allow for the identification of symptom patterns and enable swift evaluation. Moreover, these scales are widely adopted by clinical and research institutions globally, underscoring their broad acceptance. Their validity has been confirmed through psychometric testing, and they are accessible in more than 20 languages, making them usable across diverse populations. Furthermore, they exhibit minimal clinically significant differences and demonstrate high sensitivity to changes over time. Finally, these scales are freely accessible, facilitating their utilization in both clinical and research contexts48.

The strengths of the BDI-II are that it is user-friendly, applicable across international age groups (13 years and older), has a low reading level (average Flesch‒Kincaid grade level 3.6), and provides a substantial foundation for further research49.

Strengths and limitations

This study involved cancer patients from across Palestine, encompassing both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, representing diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. This is an inaugural Palestinian investigation shedding light on the occurrence of depression symptoms among cancer patients. Nonetheless, this study has several limitations. Among these limitations is its cross-sectional design, which inhibits the examination of how depression in cancer patients progresses with varying treatment modalities. Further limitations include the use of convenience sampling solely from a single tertiary hospital, a restricted sample size, and a predominantly hematologic malignancy-focused sample, potentially skewing the representation of broader cancer demographics. Consequently, the findings may lack generalizability.

Conclusions

This study highlights the high prevalence of depression symptoms among cancer patients. The beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II) score was associated with factors such as age, educational level, socioeconomic status, and smoking, underlining the complexity of addressing depression in this population. Our findings underscore the utility of the BDI-II as a tool for assessing and managing depression symptoms in cancer patients, complementing the broader spectrum of care that includes psycho-oncological and psychiatric support. This integrated approach is crucial for enhancing the quality of life of cancer patients throughout their disease trajectory.

Recommendations

-

Depression symptoms were reported and referred to a social worker or available psychosocial personnel.

-

Involve a psychiatric/mental health nurse or social worker in the session to break the bad news about the cancer diagnosis.

-

More research is recommended considering different hospitals in Palestine and sample randomization.

Data availability

The data from our surveillance are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. However, individuals interested in using the data for scientific purposes can request permission from the corresponding authors. Those with granted access will receive anonymized data to maintain patient privacy and data integrity. This manuscript is part of the Master of Community Mental Health Nursing graduation project submitted to An-Najah National University. It has been published as part of self-archiving in institutional repositories, accessible through the university repository (https://repository.najah.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/de047bba-0136-4a7b-9e9d-a484ad5126d1/content).

Abbreviations

- BDS:

-

Beck depression scale

- BDI II:

-

Beck depression inventory

- NNUH:

-

An-Najah National University Hospital

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- AutoBMT:

-

Autologous bone marrow transplant

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- USA:

-

United States of America

- PCBS:

-

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

- CES-D:

-

Center for epidemiological studies depression scale

- HADS:

-

Hospital anxiety depression scale

References

Ministry of Health. Health Annual Report, Palestine 2020. https://site.moh.ps/Content/Books/mv2fIO4XVF1TbERz9cwytaKoWKAsRfslLobNuOmj7OPSAJOw2FvOCI_DQYaIXdf2i8gCmPHbCsav29dIHqW26gZu9qJDiW2QsifZt6FrdS4H2.pdf (Accessed 2 January 2022) (2021).

Salem, H. S. Cancer status in the Occupied Palestinian Territories: Types; incidence; mortality; sex, age, and geography distribution; and possible causes. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 5139–5163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04430-2 (2023).

Halahleh, K. & Gale, R. P. Cancer care in the Palestinian territories. Lancet Oncol. 19, e359–e364. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30323-1 (2018).

Halahleh, K., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M. E. & Abusrour, M. M. Cancer in the Arab World 195–213 (Springer Singapore, 2022).

AlWaheidi, S. Promoting cancer prevention and early diagnosis in the occupied Palestinian territory. J. Cancer Policy 35, 100373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpo.2022.100373 (2023).

Derogatis, L. R. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 249, 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1983.03330300035030 (1983).

Massie, M. J. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 57–71, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014 (2004).

Cheng, B. T. et al. Palliative care initiation in pediatric oncology patients: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 8, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1907 (2019).

Boonyathee, S., Nagaviroj, K. & Anothaisintawee, T. The accuracy of the Edmonton symptom assessment system for the assessment of depression in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 35, 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117745292 (2018).

Bukberg, J., Penman, D. & Holland, J. C. Depression in hospitalized cancer patients. Psychosom. Med. 46, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198405000-00002 (1984).

Berard, R. M., Boermeester, F. & Viljoen, G. Depressive disorders in an out-patient oncology setting: Prevalence, assessment, and management. Psychooncology 7, 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199803/04)7:2%3c112::AID-PON300%3e3.0.CO;2-W (1998).

Odeh, J. B. & Qassidu, S. A. An-Najah National University Hospital (An-Najah National University, 2015).

Battat, M. et al. Factors associated with palliative care symptoms in cancer patients in Palestine. Sci. Rep. 13, 16190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43469-0 (2023).

Naja, S. et al. Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of EPDS and BDI-II as a screening tool for antenatal depression: Evidence from Qatar. BMJ Open 9, e030365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030365 (2019).

Aapro, M. & Cull, A. Depression in breast cancer patients: The need for treatment. Ann. Oncol. 10, 627–636. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008328005050 (1999).

BetterHelp. What Is The Beck Depression Inventory? https://www.betterhelp.com/advice/depression/what-is-the-beck-depression-inventory/ (Accessed 2 December 2020) (2020).

Ministry of Health. Distribution of Reported Cancer Cases by Sex & Governorate, West Bank, Palestine 2020. https://info.wafa.ps/ar_page.aspx?id=14977 (Accessed 12 July 2023) (2020).

Ripamonti, C. I. et al. The Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS) as a screening tool for depression and anxiety in non-advanced patients with solid or haematological malignancies on cure or follow-up. Support Care Cancer 22, 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2034-x (2014).

Alquraan, L. et al. Prevalence of depression and the quality-of-life of breast cancer patients in Jordan. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 13, 1455–1462. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S277243 (2020).

Marie, M., Hannigan, B. & Jones, A. Mental health needs and services in the West Bank, Palestine. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 10, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0056-8 (2016).

Dreidi, M. M., Asmar, I. T. & Rjoub, B. A. An original research about: The associations of depression and fatigue with quality of life among palestinian patients with cancer. Health Sci. J. https://doi.org/10.21767/1791-809x.1000474 (2017).

Al-Jabi, S. W. et al. Depression among end-stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis: A cross-sectional study from Palestine. Ren Replace Ther. 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-021-00331-1 (2021).

Awni Bseiso, R. & Thabet, A. M. The relationship between siege stressors, anxiety, and depression among patients with cancer in Gaza Strip. Health Sci. J. 11, 499. https://doi.org/10.21767/1791-809x.1000499 (2017).

Marie, M., SaadAdeen, S. & Battat, M. Anxiety disorders and PTSD in Palestine: A literature review. BMC Psychiatry 20, 509. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02911-7 (2020).

Marie, M. & Bataat, M. Health care access difficulties of palestinian patients in the context of mental health: A literature review study. J. Psychiatry Ment. Disord. 7, 1062 (2022).

Nazlican, E., Akbaba, M. & Okyay, R. A. Evaluation of depression in newly diagnosed breast cancer cases in Hatay province of Turkey in 2011. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 13, 2557–2561. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2557 (2012).

Vignaroli, E. et al. The Edmonton symptom assessment system as a screening tool for depression and anxiety. J. Palliat. Med. 9, 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.296 (2006).

Mystakidou, K. et al. Beck depression inventory: Exploring its psychometric properties in a palliative care population of advanced cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 16, 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00728.x (2007).

Shawawra, M. & Khleif, A. D. Palliative care situation in Palestinian Authority. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 33(Suppl 1), S64-67. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e31821223a3 (2011).

Almasri, H. & Rimawi, O. Assessment of depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy in Palestine. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2, 2787–2791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00635-z (2020).

Goldzweig, G. et al. Depression, hope and social support among older people with cancer: A comparison of Muslim Palestinian and Jewish Israeli cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 30, 1511–1519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06554-6 (2022).

Cvetkovic, J. & Nenadovic, M. Depression in breast cancer patients. Psychiatry Res. 240, 343–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.048 (2016).

Arslan, S., Celebioglu, A. & Tezel, A. Depression and hopelessness in Turkish patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 6, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7924.2009.00127.x (2009).

Abdeen, Z., Qasrawi, R., Nabil, S. & Shaheen, M. Psychological reactions to Israeli occupation: Findings from the national study of school-based screening in Palestine. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 32, 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408092220 (2008).

Tucktuck, M., Ghandour, R. & Abu-Rmeileh, N. M. E. Waterpipe and cigarette tobacco smoking among Palestinian university students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 18, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4524-0 (2017).

Jalambo, M., Alfaleet, F. & Aljazzar, S. Nutritional status, psychological stress, and lifestyle habits among cancer patients in Gaza Strip, Palestine. Int. J. Clin. Case Stud. Clin. Res. 4, 1–9 (2020).

Hirpara, D. H. et al. Severe symptoms persist for up to one year after diagnosis of stage I-III lung cancer: An analysis of province-wide patient reported outcomes. Lung Cancer 142, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.02.014 (2020).

Bazargan, M., Cobb, S., Castro Sandoval, J. & Assari, S. Smoking status and well-being of underserved African American Older adults. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 10, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10040078 (2020).

Aldaz, B. E., Treharne, G. J., Knight, R. G., Conner, T. S. & Perez, D. Oncology healthcare professionals’ perspectives on the psychosocial support needs of cancer patients during oncology treatment. J. Health Psychol. 22, 1332–1344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315626999 (2017).

Biracyaza, E., Habimana, S. & Rusengamihigo, D. Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory (BDI-II) in cancer patients: Cancer patients from Butaro Ambulatory Cancer Center, Rwanda. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 14, 665–674. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S306530 (2021).

Chaaya, M., Sibai, A. M., Fayad, R. & El-Roueiheb, Z. Religiosity and depression in older people: Evidence from underprivileged refugee and non-refugee communities in Lebanon. Aging Ment. Health 11, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860600735812 (2007).

Alduraidi, H. & Waters, C. M. Depression, perceived health, and right-of-return hopefulness of palestinian refugees. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 50, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12363 (2018).

Covey, L. S., Glassman, A. H. & Stetner, F. Depression and depressive symptoms in smoking cessation. Compr. Psychiatry 31, 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440x(90)90042-q (1990).

Glassman, A. H. et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA 264, 1546–1549 (1990).

Bjelland, I. et al. Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Soc. Sci. Med. 66, 1334–1345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.019 (2008).

Bronner, M. B., Nguyen, M. H., Smets, E. M. A., van de Ven, A. W. H. & van Weert, J. C. M. Anxiety during cancer diagnosis: Examining the influence of monitoring coping style and treatment plan. Psychooncology 27, 661–667. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4560 (2018).

Kivity, S., Shalmon, B. & Sidi, Y. Guillain-Barre syndrome: An unusual presentation of intravascular lymphoma. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 8, 137–138 (2006).

Hui, D. & Bruera, E. The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. J. Pain Symp. Manag. 53, 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370 (2017).

Halfaker, D. A., Akeson, S. T., Hathcock, D. R., Mattson, C. & Wunderlich, T. L. Pain Procedures in Clinical Practice 13–22 (Hanley & Belfus, 2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the researchers for their collaboration organized by the research center at NNUH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB proposed the project, collected the data, evaluated the findings, and authored the report. NO and MAW conducted the literature reviews and assisted with data collection. AA contributed to the study proposal and evaluated the manuscript. AAK performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, reviewed the work for intellectual content improvement, revised the manuscript, and addressed reviewer comments.. MB, RA, and HTS were responsible for data integrity, critically examined the paper for intellectual content improvement, and helped write the final version and addressed reviewer comments. SHZ conceived and designed the study, supervised the project, and participated in writing the original draft and reviewing and editing subsequent drafts. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Battat, M., Omair, N., WildAli, M.A. et al. Assessment of depression symptoms among cancer patients: a cross-sectional study from a developing country. Sci Rep 14, 11934 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62935-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62935-x

- Springer Nature Limited