Abstract

When pregnancy occur among teenagers; there is a competition for nutrients between the still-growing adolescent mother and her fetus. Pregnant adolescents’ nutrition issues are not addressed well and changes are too slow in Ethiopia. This study aimed to study, nutrition knowledge, nutritional status and associated factors among pregnant adolescents in West Arsi , central Ethiopia. We conducted a cross-sectional study of 426 pregnant adolescents between January 1 and January 25, 2023. Data were collected using kobo collect and analyzed using SPSS version 25. We performed linear regression to identify independent predictors of nutritional status and multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify nutritional knowledge. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated to show the strength of the association. Magnitude of good nutrition knowledge was 23.7%, 95% CI (21.4–25.3%), and the odds of having good nutrition knowledge was 7.5 times higher among participants whose education level was above college compared with illiterate participants [(AOR = 7.5, 95% CI = (5.27–9.38)],the odds of having good nutrition knowledge was 8 times higher among adolescent who had ANC visits, [(AOR = 8, 95% CI = (3.63–13.85)], and the odds of having good nutrition knowledge was 5 times higher among adolescents who received nutrition education [(AOR = 5, 95% CI = (3.67- 13.53)]. Receiving nutrition education (β = 0.25, P = 0.002) and good nutrition knowledge (β = 0.08, P < 0.001) were positively associated with nutritional status; however, food insecurity (β = − 0.93, P < 0.001) was negatively associated with nutritional status. The nutrition knowledge of pregnant adolescents was suboptimal; educational status, ANC visits and nutrition education were associated with good nutrition knowledge, whereas food insecurity, low nutrition knowledge, and not receiving nutrition education were predictors of poor nutritional status. Nutritional education interventions, increasing utilization of ANC, and interventions for improving food security are strongly recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutrition is key for unlocking the potential of investment in the overall health of women, children and teenagers. It is fundamental to protect females’ health and nutritional status at every stage of life to guarantee the nutrition and wellbeing of their offspring1,2. One of the most important and changeable factors affecting the health of the adolescent mother carrying a fetus, as well as the chronic conditions that affect adults, is thought to be her nutritional status. Teenagers' long-term health trajectory may be altered by dietary behaviors that are positively influenced by good nutritional knowledge3,4. Ensuring a robust biological basis for the present and future health, welfare, and productivity of women is contingent upon receiving adequate nutrition during the critical phase of adolescent growth and development5.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescence as the period between the ages of 10 and 19 years. Adolescents who are pregnant are more likely to experience a number of unfavorable growth and developmental outcomes, which can have an adverse effect on mothers’ risk of early cessation of linear growth6, and her offspring's risk of low birth weight and small for gestational age7. According to research conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), teenage girls may even cease growing as a result of becoming pregnant6,7.

In females, physiological conditions such as pregnancy and lactation increase the likelihood of nutritional risks. Childbearing during adolescence has been found to hinder the postmenarcheal linear and ponderal growth of young girls during the potential window of opportunity for catch-up growth in an undernourished population8,9,10. When the pregnant diet does not supply the required nutrients for her needs or for those of the fetus, the fetal requirements are met by withdrawing these nutrients from the tissues of the pregnant mother. This tissue depletion weakens the mother and increases the probability of serious complications9,11,12,13,14.

Nutritional knowledge is essential for ensuring that pregnant individuals receive proper nutrition and maintain good health15. A lack of knowledge can lead to malnutrition and poor health16. One of the components of adopting a healthier nutritional practice is having knowledge about nutrition and health, which is indicative of dietary habit modification. Pregnant adolescents are therefore expected to possess the knowledge essential to maintain optimum health and nutrition during pregnancy17.

Several studies have been conducted in Ethiopia in relation to pregnant adolescent nutrition. For example, a study conducted in West Arsi revealed a very high magnitude of undernutrition (34%) among pregnant adolescents18, and a study in southern Ethiopia showed a 26.4% magnitude of undernutrition19. Moreover, a study in Arsi on pregnant adults showed that participants have limited knowledge and poor dietary diversity practices20. There are efforts in nutrition intervention programs and strategies in Ethiopia21,22; however, pregnant adolescents’ nutritional issues have not been well addressed, and changes have been made too slow.

A cross sectional study in the Ledzokuku-Krowor Municipality, Ghana showed that, less than half (44.9%) of the pregnant adolescents have high nutritional knowledge and about 19.4% of them have good eating habits23, similar study in Mandera Kenya showed that less than half of the mothers (47.5%) had moderate nutrition knowledge and Only 13.5% had a high knowledge24.

Most related studies have focused on pregnant mothers in general, with little focus on those who are adolescents, and most of these studies have been conducted in developed countries, with only a few in developing countries25,26, where a large percentage of the problem occurs. Insufficient attention has been given to the nutritional knowledge and nutritional status of pregnant adolescents. Nutritional knowledge affects dietary practices and nutritional status. Investigating nutritional knowledge and nutritional status among pregnant adolescents is important when designing appropriate interventions; therefore, this study aimed to evaluate nutritional knowledge, nutritional status and associated factors among pregnant adolescents in the West Arsi Zone, central Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study setting and design

We conducted a community-based cross-sectional study among pregnant adolescents in West Arsi, central Ethiopia. The zone is in the Oromia region, 250 km from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital city. The West Arsi Zone has 16 districts. The total population was estimated to be 2,929,894 in mid-2022. The zone covers an area of 12,556 sq.km, with a climate of 45.5% highland, 39.6% midland, and 14.9% lowland. Agriculture is the dominant means of livelihood in this zone27. According to the Zonal report of 2022, there are 417 public health facilities, 5 of which are hospitals, 324 of which are health posts, 88 of which are health centers, and 203 of which are private medium and higher clinics, including one nongovernmental hospital and two private hospitals providing health services. At least one sexual and reproductive health (SRH) service was utilized in the zone in 2019, for which 58.6% of the population was utilized [102, 103]. This study was conducted between January 1 and January 25, 2023.

Source population and study population

All pregnant adolescents in the West Arsi Zone were the source population, whereas those in the selected kebeles were the study population.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criterion for pregnant adolescents was gestational age prior to 16 weeks of pregnancy, as this information is the baseline of a cluster-randomized controlled community trial that was registered with Pan African Clinical Trials.gov under the identification code PACTR202203696996305 and with the title "Effect of nutritional behavioral change communication intervention on maternal outcomes among pregnant adolescents in the West Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial".

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant adolescents who were diseased or unable to provide data at the time of data collection were excluded.

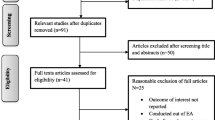

Sample size determination and sampling technique

The sample size was determined using a single-population proportion formula. with the assumption of a 95% confidence level (Z α/2) and a 0.05 expected margin of error (d). proportion (p) of good nutritional knowledge among pregnant women in Ambo Town, Ethiopia (33%)28.

This is part of an RCT study reporting baseline findings; the sample size for other objectives was 459 [PACTR202203696996305]. ], which was greater than 339; therefore, the final sample size was 459.

Pregnant teenagers were identified using a multistage clustered sampling method. In the first stage, four districts were randomly selected from the zone's sixteen districts. In the second phase, 16 kebeles (clusters), the lowest administrative unit, were chosen randomly from the districts that were considered. Subsequently, house-to-house visits were made to each of the selected kebeles to count pregnant adolescents to identify pregnant adolescents who qualified for particular clusters by asking about their most recent menstruation and confirmation via a pregnancy test. This study was conducted on all eligible pregnant adolescents. All pregnant adolescents in the selected kebeles were included in the study, with an average cluster size of 29.

Data collection procedure and measurements

To obtain this information, we employed a pretested structured questionnaire. The questionnaire asked about health service use, frequency of meals, sociodemographic characteristics, household decision-making, the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), and nutritional knowledge. Six clinical nurses and two master of public health (MPH) holders worked as supervisors and data collectors, respectively. The pregnancy tests were conducted by three female laboratory technicians. To complete the questionnaire, the data collectors conducted in-person interviews with participants at their homes. To the greatest extent possible, other family members were not permitted to enter the site of the interviews to preserve the adolescent's privacy.

The MUAC (mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC)) was measured using inelastic insertion-type tape from each adolescent mother’s left arm at the midpoint between the tips of the shoulder (olecranon process) and elbow (acromion process). The MUAC was measured while the adolescent stood up relaxed with her hand hanging down. After checking that the tape was applied with the correct tension (neither too loose nor too tight), the MUAC of the adolescent was read and recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. MUAC measurements were taken with a pair of data collectors following the recommended measurement technique29.

Dietary intake was calculated using the 24-h recall method according to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) III recommendations of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) to assess whether the diets of pregnant teenagers were adequately diverse30. According to the recommendations, there are ten food groups, including grains, meat, nuts and seeds; eggs; plantains; white roots; tubers; pulses (peas, beans, and lentils); dairy, poultry and fish; dark green leafy vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables rich in vitamin A, other vegetables and other fruits. A pregnant adolescent was considered to have consumed a sufficiently diverse diet if she had consumed at least five of the ten food groups in the 24 h prior to data collection31,32. Pregnant adolescents were asked to list every meal they had and drink they had consumed during the preceding 24 h, both inside and outside the home. In addition, the participants were asked to recall any between-meal snacks they may have had. Food groups were scored as "1" for consumption over the reference time and "0" for nonconsumption.

The food security assessment was conducted using the HFIAS Guidelines32. The degree of food security in the household was assessed using 27 questions from the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale. The questions were previously authorized for use in developing countries.33 Households are labeled food-secured if they experienced fewer than the first two food insecurity indicators. Households that experienced between two and ten, 11 and 17, or more than 17 food insecurity indicators were categorized as mildly, moderately, or severely food insecure, respectively.

The wealth index of the household was determined through the application of principal component analysis (PCA), considering factors such as agricultural land, household possession, animals, water supply, and latrine access. Three categories were created from all the responses for the nondummy variables. The code for the highest rating was 1. Nevertheless, codes of 0 were assigned to two lower numbers. Factor scores in PCA were produced with variables having a commonality value higher than 0.5. The score for each family's first primary component was retained to calculate the wealth score. The quartiles of the wealth score were developed to classify households as the poorest, poor, medium, rich, or richest34.

Pregnant teenagers were asked eight questions to gauge their level of autonomy. For every question, code one was provided if the adolescent made the decision on her own or in conjunction with her husband; otherwise, code zero was provided The mean35. was used to classify pregnant adolescents’ decision-making abilities.

Maternal knowledge of food intake during pregnancy was assessed using a set of twelve questions. A code of one was given for a correct response, and a code of zero was given for an incorrect response. Pregnant adolescents who scored ≥ 75% on the knowledge questions were considered to have good knowledge; otherwise, they were considered to have a low knowledge score36.

Operational definition

Pregnant adolescent: Pregnant girls within 10–19 years of age3.

Nutrition knowledge: is pregnant adolescent knowledge regarding optimal nutrition during pregnancy and it is scored as: Pregnant adolescent who score > = 75 and > 50% from 12 knowledge questions were labeled as having high and medium knowledge scores, respectively. Otherwise, they are considered to have low knowledge score 2734.

Data quality control

We used a standard-adapted questionnaire and adhered to the steps needed to produce the desired results, and the highest level of data quality possible was ensured. To maintain consistency, the questionnaires were translated into the local languages Amharic and Afan Oromo and then translated back into English. Pretests were also conducted on 23 pregnant adolescents in the Wondo Genet district. A test–retest method was used for reliability analysis of the pregnant adolescent nutrition knowledge variable, a Cronbach coefficient of 0.83 was obtained after pre-test. Based on the gaps found during the pretest, changes were made to the data-gathering methods to improve their reliability. The principal investigator provided a two-day training session for supervisors and data collectors regarding the objective and methodology of the data collection. Supervisors monitored field practices and reviewed the completed surveys daily to ensure data accuracy.

Data management and statistical analyses

We collected the data using Kobo Collect/Toolbox and exported the data to SPSS version 25 for cleaning and analysis. A bivariate logistic regression model was applied to identify the independent predictors of nutritional knowledge. In the bivariate analysis, variables with p values less than 0.25 were added to the multivariable logistic regression model. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs), crude and adjusted odds ratios (CORs), and AORs were used to calculate the strength of the relationship. According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, variables with a P value of 0.05 or lower were regarded as independent predictors of nutritional knowledge.

Univariate linear regression analyses were also conducted before the multivariable linear regression analysis. To identify the predictors of MUAC (nutritional status), multivariable linear regression analysis with stepwise variable selection was employed, and variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate analyses were entered into the multivariable linear regression.

The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed using adjusted R2 (R2 = 33.8%), and partial regression residual plots showed that all the models had a linear relationship. The normality of the data was assessed using a Q‒Q plot, and there was no need for transformation. Outliers and influential observations were not as influential and were retained in the final model. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF); the maximum VIF was 1.4, and interaction and confounding variables were checked. All tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. We present the results of the linear regression as parameter estimates (β), P values, and 95% confidence intervals. The percentage of missing data was low; therefore, the imputation method for missing data management was used.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Jimma University IRB/Ethics Committee (reference number JUIH/IRB/194/22). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations; the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before providing informed consent, each study participant provided a detailed description of the study's title, objective, protocol, and duration, as well as its risks and benefits. Each adolescent provided verbal, written, and signed informed consent forms before any measurements or interviews. Participants were made aware of the publication of their anonymous comments. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the commencement of the interviews. The researcher was satisfied with the academic and ethical requirements. Finally, the researcher kept the data in a locked file cabinet in a safe place after the completion of the study. Informed consent was obtained from both the adolescents and their husbands or parents.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant adolescents

Of the 459 pregnant adolescents invited to participate in this study, 426 fully participated, for a response rate of 92.8%. The mean (± SD) age of the pregnant adolescents was 18.6 (± 0.74) years. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Nutrition knowledge among pregnant adolescents

Approximately 101 (23.7%) 95% CI (21.4–25.3%) of the study participants had good nutritional knowledge, and 76.3% had poor nutritional knowledge.

Dietary diversity practice and food security of participants

Twenty one percent of the pregnant adolescents had adequate dietary diversity practice and 78% had inadequate dietary diversity practice during the preceding 24 h of the survey (95% CI (74.3%, 82.8%)). The most frequently eaten foods were pulses (79%) and starchy foods (81.3%) and the least consumed foods were, fruits (3.48%) and meats (2.8%). 319 (74.8%) of the participants are food insecure and 107 (25.2%) are food secured.

Factors associated with nutritional knowledge among pregnant adolescents

Educational status, occupation of the pregnant adolescent, ANC visits, and nutritional education were significant factors in the bivariable logistic regression analysis, and educational status, ANC visits, and nutritional education remained significantly associated with good nutritional knowledge at the multivariable logistic regression level.

The odds of having good nutritional knowledge were 7.5 times greater among pregnant adolescents whose highest education attained was college education or above than among participants with no formal education [AOR = 7.5, 95% CI = (5.27–9.38)], P = 0.002; the odds of having good nutritional knowledge were 8 times greater among pregnant adolescents who had ANC visits than among those who had no ANC visit [AOR = 8, 95% CI = (3.63–13.85)], P < 0.001; and the odds of having good nutritional knowledge were 5 times greater among pregnant adolescents who received nutritional education and counseling than among those who did not receive nutritional education [AOR = 5, 95% CI = (3.67–13.53)], P < 0.001]. (Table 2).

Nutritional education (β = 0.25, P = 0.002) and good nutritional knowledge (β = 0.08, P < 0.001) were positively associated with MUAC (nutritional status). However, food insecurity (β = − 0.93, P < 0.001) was negatively associated with the MUAC (nutritional status). (Table 3).

Discussion

This study revealed that the magnitude of good nutritional knowledge was 23.7%, and the educational status of the pregnant adolescents, ANC visits, and nutritional knowledge were significantly associated with good nutritional knowledge. Nutrition education and good nutritional knowledge were positively associated with nutritional status, and food insecurity was negatively associated with nutritional status.

The magnitude of good nutritional knowledge in this study (23%) was lower than that in other studies, such as the studies conducted in Ambo, Ethiopia (33%),37 Guto Gida, East Wellega, Ethiopia (64.4%)38, Accra, Ghana (44.9%),39, and Sialkot, Pakistan (47.5%)40. This might be because of the differences in study settings (community-based vs. facility-based) and differences in sociodemographic and economic factors. Moreover, these studies included pregnant women and pregnant adolescent participants, whereas the current study included pregnant adolescents who were less mature. The large nutritional knowledge gap reported in this study implies that health care providers, including health extension workers, planners, and community health agents, should work to improve the nutritional knowledge of pregnant adolescents. Nutritional knowledge alone cannot guarantee an individual’s good behavior, but it is a predisposing factor that can significantly shape their attitudes, which can be reflected in a person’s actions.

The odds of having good nutritional knowledge were 7.5 times greater among pregnant adolescents whose highest education attained was college education or above than among participants with no formal education; this finding is consistent with several studies, such as the studies conducted in Ambo, Ethiopia37, East Wellega, Ethiopia,38 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,41, and Klang Valley, Malaysia42; This could be because pregnant adolescents with higher education levels can more effectively use textual resources for information, such as books, newspapers, flyers, Internet articles and other educational materials. Less educated mothers deserve more attention, and they should receive intensive nutrition education in simple language and ways they can understand.

The odds of having good nutritional knowledge were eight times greater among pregnant adolescents who had ANC visits; this finding is in agreement with the findings of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia41, the Harari region in Eastern Ethiopia42, and Beirut and Lebanon43. The ANC programme offers resources to support preventative healthcare behaviors, enhance health literacy, and enhance nutrition. During their ANC appointments, pregnant women have plenty of time to talk about eating healthily. There is low pregnancy attendance in ANC services in Ethiopia44, and this need needs to be improved to equip pregnant women with the necessary nutritional education and other health services.

The odds of having good nutritional knowledge were five times greater among pregnant adolescents who received nutrition education and counseling than among participants who did not receive nutrition education, which is consistent with the findings of a study conducted in Ambo, Ethiopia37. Nutritional education is essential for improving food and nutritional literacy in pregnant women. The nutritional knowledge of pregnant individuals can be directly improved by providing nutritional and health information; pregnant adolescents need to be given sufficient nutritional education at both the facility and community levels to improve their dietary practices, which ultimately results in good pregnancy outcomes.

Good nutritional knowledge was positively associated with the nutritional status of pregnant adolescents, which is in agreement with the findings of previous studies in the Silte zone, southern Ethiopia45, and Klang Valley, Malaysia46. People’s literacy about the consumption of food is very significant and determines their food choices and habits. Nutritional knowledge is an important determinant of good dietary practices47,48, and good dietary practices can lead to better nutritional status49,50.

Receiving nutrition education was positively associated with the nutritional status of pregnant adolescents, which is similar to the findings of a study conducted in Dessie Town, northeastern Ethiopia51. Nutrition education can enhance pregnant adolescents’ understanding of optimal nutrition, leading to an improvement in their nutritional status. Their increased understanding will enable them to begin healthy eating habits, which in turn will improve their nutritional condition.

Being food insecure was negatively associated with the nutritional status (measured by MUAC) of pregnant adolescents, which is consistent with the findings of studies conducted in Ambo, Ethiopia37, rural Ethiopia52, and a systematic review conducted globally53. Food insecurity or eating food that does not contain all the essential nutrients for good nutritional status is an immediate cause of undernutrition. There is a commitment to advancing maternal and child nutrition across states through the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals54; preventing and managing food insecurity is very important for achieving this global goal.

In this community-based study, pregnant adolescents were visited at their homes to provide primary data. Recall bias could exist because of the respondents' potential to forget certain facts. However, to reduce recall bias, the data collectors received training on how to elicit information from pregnant adolescents. However, further studies are needed to investigate the magnitude of undernutrition based on validated specific cut-off point for pregnant adolescent.

Conclusion

The nutritional knowledge of pregnant adolescents was suboptimal; educational status, ANC visits, and receiving nutrition education were associated with good nutritional knowledge, whereas food insecurity, low nutritional knowledge, and not receiving nutrition education were predictors of poor nutritional status. Nutritional education and counseling interventions, increasing the utilization of ANC, and interventions for improving food security and randomized control trail using nutrition behavioral change communications are strongly recommended.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

References

Branca, F. et al. artineNutrition and health in women, children, and adolescent girls. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 351, h4173. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4173 (2015).

Keeley, B., C. Little, and E. Zuehlke, The State of the World's Children: Children, Food and Nutrition--Growing Well in a Changing World. UNICEF, 2019 DOI: http://www.unicef.org/education. 2019

Azar, B. Adolescent pregnancy prevention highlights from a citywide effort. Am. J. Public Health 102(10), 1837–1841. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300935 (2012).

Wallace, J. et al. Nutritional modulation of adolescent pregnancy outcome–a review. Placenta 27, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.002 (2006).

WHO. WHO Guidelines on Preventing Early Pregnancy and Poor Reproductive Outcomes Among Adolescents in Developing Countries. Geneve, Switzeland: World Health Organization (2011).

Rah, J. H. et al. Pregnancy and lactation hinder growth and nutritional status of adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. J. Nutr. 138, 1505–1511 (2008).

Casanueva, E., Rosello-Soberon, M. E., De-Regil, L. M., Arguelles Mdel, C. & Cespedes, M. I. Adolescents with adequate birth weight newborns diminish energy expenditure and cease growth. J. Nutr. 136, 2498–2501 (2006).

Mudor, H. & Bunyarit, F. A prospective of nutrition intake for pregnant women in Pattani, Thailand. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 91, 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.08.415 (2013).

USAID. Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy Technical Guidance Brief: Maternal Nutrition for Girls Women 1–104 (USAID, 2014).

Zelalem, T., Erdaw, A. & Tachbele, E. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant women who attend antenatal care at public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery. 10(7), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJNM2017.0289 (2018).

Goli, S., Rammohan, A. & Singh, D. The effect of early marriages and early childbearing on women’s nutritional status in India. Matern. Child Health J. 19(8), 1864–1880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1700-7 (2015).

Goshu, H., Teshome, M. S. & Abate, K. H. Maternal dietary and nutritional characteristics as predictor of newborn birth weight in Jimma Town, Southwest Ethiopia. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 10(5), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPHE2017.0977,2018 (2017).

Rah, J. H. et al. Difference in ponderal growth and body composition among pregnant versus never-pregnant adolescents varies by birth outcomes. Matern. Child Nutr. 6(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00197 (2010).

Rah, J. H. et al. Pregnancy and lactation hinder growth and nutritional status of adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. J. Nutr. 138(8), 1505–1511. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/138.8.1505 (2008).

DiMeglio, G. Nutrition in adolescence. Pediatr. Rev. 21(1), 32–33. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.21-1-32 (2000).

Gong, E. J. & Spear, B. A. Adolescent growth and development: Implications for nutritional needs. J. Nutr. Educat. 20(6), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(88)80003-7 (1988).

Nguyen, P. H. et al. The nutrition and health risks faced by pregnant adolescents: Insights from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. PloS One 12(6), e0178878. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178878 (2017).

Belete, Y., Negga, B. & Firehiwot, M. Under nutrition and associated factors among adolescent pregnant women in shashemenne district, West Arsi Zone, Ethiopia: A community-based study. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 6, 454. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000454 (2016).

Yimer, B. & Wolde, A. Prevalence and predictors of malnutrition during adolescent pregnancy in southern Ethiopia: a community-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1), 1–7 (2022).

Zerfu, T. A. & Biadgilign, S. Pregnant mothers have limited knowledge and poor dietary diversity practices, but favorable attitude toward nutritional recommendations in rural Ethiopia: Evidence from community-based study. BMC Nutr. 4, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-018-0251-x (2018).

Zelalem, M. The seqota declaration: From proof of concept to expansion phase. UN Nutr. 19, 134 (2022).

Bahru, B. A., Jebena, M. G., Birner, R. & Zeller, M. Impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety net program on household food security and child nutrition: A marginal structural modeling approach. SSM-Popul. Health 12, 100660 (2020).

Kennedy, E. et al. Nutrition policy and governance in Ethiopia: What difference does 5 years make?. Food Nutr. Bull. 41(4), 494–502 (2020).

Ayele, S., Zegeye, E. A., Nisbett, N. Multisectoral nutrition policy and programme design, coordination and implementation in Ethiopia., https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/15200 (2020)

Hall, M. V. Nutritional status in pregnant adolescents: A systematic review of biochemical markers. Matern. Child Nutr. 3(2), 74–93 (2007).

Marvin-Dowle, K., Burley, V. J. & Soltani, H. Nutrient intakes and nutritional biomarkers in pregnant adolescents: A systematic review of studies in developed countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 1–24 (2016).

West Arsi zone area description, https://dbpedia.org/page/West_Arsi_Zone , accessed on June 27, 2023

Tariku, Y. & Baye, K. Pregnant mothers diversified dietary intake and associated factors in southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Metabolism 2022, 4613165. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4613165 (2022).

Cogill, B. Anthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide, Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (Academy for Educational Development, 2003).

FAO FHI360, Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women: A Guide for Measurement, FAO, Rome, Italy, 2016.

FAO U. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA). Rome (2016).

Coates, J., Swindale, A. & Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide: Version 3 (2007).

Gebreyesus, S. H., Lunde, T., Mariam, D. H., Woldehanna, T. & Lindtjørn, B. Is the adapted household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) developed internationally to measure food insecurity valid in urban and rural households of Ethiopia?. BMC Nutr. 1, 2 (2015).

Demilew, Y. M., Alene, G. D. & Belachew, T. Dietary practices and associated factors among pregnant women in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20(1), 1–11 (2020).

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa and Rockville: CSA and ICF; 2016

Tenaw, Z., Arega, M. & Tachbele, E. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant women who attend antenatal care at public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery. 10(7), 81–89 (2018).

Gebremichael, M. A. & Lema, T. B. Prevalence and predictors of knowledge and attitude on optimal nutrition and health among pregnant women in their first trimester of pregnancy. Int. J. Women’s Health https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S415615 (2023).

Daba, G., Beyene, F., Fekadu, H. & Garoma, W. Assessment of knowledge of pregnant mothers on maternal nutrition and associated factors in Guto Gida Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 3(6), 1 (2013).

Appiah, P. K., Korklu, A. R. N., Bonchel, D. A., Fenu, G. A. & Yankey, F.W.-M. Nutritional knowledge and dietary intake habits among pregnant adolescents attending antenatal care clinics in urban community in Ghana. J. Nutr. Metabol. 2021, 8835704. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8835704 (2021).

Abbas, S., Anjum, R., Raza, S. & Shabbir, A. Knowledge about maternal under nutrition on obstetric outcomes in young pregnant women in Sialkot-Pakistan. J. Pak. Soc. Intern. Med. 2(3), 218–220 (2021).

Tesfa, S., Aderaw, Z., Tesfaye, A., Abebe, H. & Tsehay, T. Maternal nutritional knowledge, practice and their associated factors during pregnancy in Addis sub city health centers, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Africa Nurs. Sci. 17, 100482 (2022).

Roba, A. A. et al. Antenatal care utilization and nutrition counseling are strongly associated with infant and young child feeding knowledge among rural/semiurban women in Harari region, Eastern Ethiopia. Front. Pediatr. 10, 1013051 (2022).

Abou Haidar, M. Y. & Bou, Y. E. Knowledge, attitude and practices toward nutrition and diet during pregnancy among recently delivered women of Syrian refugees. J. Refugee Global Health 1(2), 6 (2018).

Arefaynie, M. et al. Number of antenatal care utilization and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: zero-inflated Poisson regression of 2019 intermediate Ethiopian Demography Health Survey. Reproduct. Health 19(1), 1 (2022).

Muze, M. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of undernutrition among pregnant women visiting ANC clinics in Silte zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 707. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03404-x (2020).

Manaf, Z. A. et al. Nutritional status and nutritional knowledge of Malay pregnant women in selected private hospitals in Klang Valley. J. Sains Kesihat Malays. 12, 53–62 (2014).

Wang, W. C., Zou, S. M., Ding, Z. & Fang, J. Y. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant females in Shenzhen China: A cross-sectional study. Prev. Med. Rep. 18(32), 102155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102155 (2023).

Gezimu, W., Bekele, F. & Habte, G. Pregnant mothers’ knowledge, attitude, practice and its predictors toward nutrition in public hospitals of Southern Ethiopia: A multicenter cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 10, 20503121221085844. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121221085843,2022 (2022).

Acosta, P. et al. Dietary practices and nutritional status of children served in a social program for surrogate mothers in Colombia. BMC Nutr. 9, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-023-00685-1 (2023).

Nicholaus, C., Martin, H. D., Kassim, N., Matemu, A. O. & Kimiywe, J. Dietary practices, nutrient adequacy, and nutrition status among adolescents in boarding high schools in the kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. J. Nutr. Metabol. 2020, 3592813. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3592813 (2020).

Diddana, T. Z. Factors associated with dietary practice and nutritional status of pregnant women in Dessie town, northeastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 517. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2649-0 (2019).

Roba, K. T. et al. Seasonal variations in household food insecurity and dietary diversity and their association with maternal and child nutritional status in rural Ethiopia. Food Secur. 11, 651–64 (2019).

Demétrio, F., Teles, C. A., Santos, D. B. & Pereira, M. Food insecurity in pregnant women is associated with social determinants and nutritional outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 25, 2663–76 (2020).

Grosso, G., Mateo, A., Rangelov, N., Buzeti, T. & Birt, C. Nutrition in the context of the sustainable development goals. Eur. J. Public Health 30(1), i19-23 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deepest gratitude to all the study participants who participated in the study and all the staff of Jimma University and Dilla University, the data collectors, and the supervisors who sacrificed their precious time for the success of this study.

Funding

Dilla University and Jimma University in collaboration support this study. Funding number for Dilla University is DU035 and funding number for Jimma. University is ju04/2022. The role of the funding organization is only financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T., D.T., and T.B. were involved in the design and selection of the articles, analysis, and manuscript writing. All the authors were involved in the analyses, manuscript preparation, and editing. All the authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript. All the authors gave their final approval for the version that would be published, agreed to the journal to which the article would be submitted, and agreed to be responsible for all aspects of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tesfaye, A., Adissu, Y., Tamiru, D. et al. Nutritional knowledge, nutritional status and associated factors among pregnant adolescents in the West Arsi Zone, central Ethiopia. Sci Rep 14, 6879 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57428-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57428-w

- Springer Nature Limited