Abstract

Early and prompt treatment-seeking for malaria is necessary to reduce the progression of the disease to its severe forms and the associated mortality. Various studies have indicated that treatments sought for malaria were not always within the recommended timeframe. Therefore, this study aims to assess factors influencing delay in malaria treatment seeking at public health facilities in South Gonder, Ethiopia. An unmatched case–control study was conducted among 322 individuals, comprising 161 cases and 161 controls, who were randomly selected malaria patients visiting public health facilities in South Gonder District, Ethiopia, from May 20/2022 to June 25/2022. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data, which were subsequently cleaned and entered into Epi data. Descriptive statistics were performed, and variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.25 from the bivariate analysis were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Significant variables with a p-value of < 0.05 were retained in the multivariable model. Patients who were unable to read and write [AOR = 3.47 (1.01–11.9)], fear of side effects of malaria treatment drugs [AOR = 1.89 (1.04–3.42)], lack of access to health education malaria disease and its treatment [AOR = 1.93 (1.02–3.65)], lack of transportation access [AOR = 4.70 (1.73–12.7)], not membership of community-based health insurance [AOR = 2.5 (1.3–4.82)] and lack of confidence on malaria care health facility providing [AOR = 2.14 (1.06–4.29)], were found to be determinants of treatment-seeking delay among malaria patients. In Summary, this study revealed significant associations between delays in seeking malaria treatment and factors such as educational status (those who were unable to read and write), malaria drug side effects, health education on malaria, transportation access, CBHI membership, and confidence in health malaria care. it is recommended that targeted interventions and awareness campaigns be implemented to address these determinants, promoting prompt and effective malaria treatment-seeking behavior in the studied population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria, a communicable disease caused by the Plasmodium parasite and transmitted through Anopheles mosquitoes, is a significant global health concern1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes key pillars for effective malaria prevention and control, with a crucial focus on ensuring universal access to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment3,4. The impact of malaria is particularly pronounced in sub-Saharan Africa, where 90% of all malaria-related deaths occur, making it a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide3,5. Early and appropriate treatment plays a pivotal role in preventing the progression of malaria to severe stages, ultimately reducing morbidity and mortality while limiting further transmission6. An additional objective of early diagnosis and treatment is to diminish the reservoir of individuals carrying the malaria parasite, thereby lowering the risk of transmission within the community. Recognizing these critical aspects, it is recommended that individuals gain access to early diagnosis and receive prompt, effective treatment within 24 h of experiencing malaria symptoms7,8.

Different studies have revealed that delay in treatment-seeking is a problem, and its burden is higher in regions with a higher malaria prevalence. The East Asian region is one such area with a high malaria burden, where the delay in treatment-seeking is surprisingly 100%. The lowest percentage of delay experienced in this region was 79.4%. In the African continent delay in treatment-seeking for malaria ranges from 36.6 to 87.8%8. In Ethiopia in particular, delay in treatment-seeking for malaria ranges from 28.7 to 52.4%, which is still far from the country's target of zero percent delay8,9,10,11.

The National Malaria Control Programme(NMCP) 2017–2020 which Ethiopia is implementing specifies that 100% of suspected malaria cases should be diagnosed within 24 h of the onset of symptoms12,13. However, contrary to this ambitious goal, studies conducted in some parts of the country revealed that the percentage of patients seeking treatment within the recommended 24 h of onset of symptoms is very low9,14,15. Even among the findings of studies in Ethiopia, the maximum percentage of malaria patients who sought treatment within 24 h of the onset of symptoms is 52.4%, which is only half of Ethiopia's national target16,17.

Socio-demographic characteristics, physical accessibility & environmental factors, experience & behavioral factors, and knowledge about malaria were reported as factors affecting treatment-seeking in different studies15,17. Several behavioral aspects contribute to this delay, including a lack of knowledge about malaria symptoms, belief in traditional remedies, fear of negative side effects of medication, financial constraints, and distance to health facilities. Patients may also be deterred by stigma associated with seeking medical care, perception of mild illness, and perceived low quality of care in public facilities18,19.

In Ethiopia, most of the studies about factors associated with delay in treatment-seeking were confined to under-five children9,20. Even though children of age less than 5 years are in the high-risk group for malaria, it is also important to consider the older population because, according to Ethiopia’s 2019 malaria report, during the last 6 years numbers have shown that 80% of malaria victims were adults and children at least 5 years of age21.

Additionally, the South Gonder District is an area where malaria is prevalent. Understanding the factors that contribute to delays in seeking treatment among malaria patients in this district can provide valuable insights for health program planners, NGOs, researchers, and other organizations dedicated to reducing the impact of malaria on mortality and morbidity. While previous studies have explored various aspects of malaria prevention and control, there is a noticeable lack of comprehensive investigations into the specific factors that contribute to delays in seeking treatment at public health facilities in the South Gonder region. The study addresses crucial gaps in understanding factors contributing to delays in malaria treatment seeking, offering valuable insights for policymakers, partners, and implementers in malaria prevention, control, and elimination efforts, Therefore, this study aimed to assess factors influencing delay in malaria treatment seeking at public health facilities in South Gonder, Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study design and period

A facility-based, unmatched case–control study was carried out, involving 322 randomly selected malaria patients (161 cases and 161 controls) in public health facilities in South Gonder District, Ethiopia from May 20/2022 to June 25/2022. South Gonder District is situated in the Amhara region, in the north-central part of Ethiopia, positioned between 11°8' N and 39°38' E latitude and 11.133° N 20' and 39.633° E longitude. The district spans an elevation range from 2470 to 16,840 m above sea level, covering a surface area of approximately 16,840 km2. In terms of geographical proximity, South Gonder District is located 666 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 97 km from Bahir Dar, the capital city of the Amhara Region.

Population

All confirmed malaria patients who seek treatment in public health facilities of South Gonder District were taken as the source population. All confirmed malaria patients who sought treatment in public health facilities of South Gonder District during the data collection period were considered as the study population.

Cases: Identified as a malaria patient who seeks treatment after 24 h of the onset of the first symptoms of malaria22.

Controls: Identified as a malaria patient who seeks treatment within 24 h of onset of the first symptom of malaria23.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All confirmed malaria patients for Plasmodium species by blood film (Bf) or rapid diagnostic test (RDT) enrolled in the study were included in the study. While those who were critically ill were excluded from the study.

Sampling method and sample size determination

The sample size was determined by using the double population proportion formula for the case–control study in Epi-info 7.0 stat calc. The calculation was computed by taking three variables; the presence of side effects, knowledge of malaria, and distance of the health facility which are significantly associated with treatment-seeking delay in most studies. The final sample size was calculated by using the assumption of "presence of side effect" with the odds ratio of 4.96, the percent of controls exposed at 2.6%, the percent of cases exposed at 11.7% with a 95% confidence interval, power being 80%, case to control the ratio of 1:1 and by adding 10% nonresponse rate20. The total number of malaria patients was 17,622 from public health facilities. The study's ultimate sample comprised 322 participants, evenly divided into 161 cases and 161 controls at a one-to-one ratio. Both cases and controls were chosen separately through a systematic random sampling method. Cases were initially selected using a lottery, and subsequently, every fourth interval was chosen, as illustrated below. (Table 1).

Ninety-six public health facilities exist in South Gonder District, and for participant selection, nine were chosen randomly through a lottery method. This approach ensured an equal opportunity for all facilities, maintaining a fair and unbiased selection process. Cases were included by using a systematic random sampling technique by calculating the sampling interval for cases based on the average monthly cash flow of each health facility while controls were selected as cases were enrolled.

The Kth (K = 4) value was determined for both cases and controls; it was done separately by dividing the patient flow by sample size (the total malaria patient flow of South Gonder District of month June 2013 E.C was 1288 from the data that was collected from each facility. The study subject was selected by using systematic random sampling techniques after a laboratory request was done and when patients those positive for any species of Plasmodium, they were eligible and were moved to a private room for an interview until the total required sample size was obtained.

Operational definitions

Knowledge about malaria

Assessed by ten knowledge assessment questions and those who scored 70% and more were considered as having adequate knowledge and those who scored less than 70% on knowledge assessment questions were considered as having inadequate knowledge24.

Timely treatment-seeking

This is a treatment sought for symptoms of malaria within 24 h of the onset of symptoms23,25.

Delayed treatment-seeking

This is a treatment sought after the recommended time of 24 h onset of malaria symptoms23,25.

Waiting time

The time a patient had to wait at registration, consultation, laboratory, and other diagnostic units and at the pharmacy to receive service. If the patient's waiting time is greater or equal to 120 min considered a long waiting time and if the waiting time is less than 120 min it is considered a short waiting time22.

Client satisfaction

A subjective measure of whether a patient’s expectations about a health encounter were met22.

Confidence in healthcare

Confidence in the healthcare system implies an expectation that sufficient and appropriate treatments will be provided if needed23.

Data collection procedure and quality assurance

The questionnaire was initially developed in English by reviewing available literature. The training was given to data collectors and a supervisor. Data were collected by a structured pre-tested questionnaire which was developed by reviewing different peer-reviewed literature26,27. The tool consists of sociodemographic characteristics, physical accessibility and environmental factors, behavioral factors, and questions on treatment-seeking delay. Additionally, knowledge assessment questions on signs/symptoms, transmission, and prevention of malaria were partially adapted from a previously conducted study which contains 12 closed-ended and multiple choice questions where each choice has a score of 1 point27,28.

Data processing and analysis

After ensuring completeness and consistency, the data underwent coding and entry into EPI-data v 4.6.0.2, followed by exportation to SPSS 23 statistical software for processing and analysis. Frequency tables and descriptive summaries were employed to depict study variables. Logistic regression analysis assessed the significance of associations between dependent and independent variables. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between treatment-seeking delay among malaria patients and selected independent variables. In bivariate logistic regression, variables with a p-value of 0.25 or less were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis29, then p value less than 0.05 was considered a predictor for the delay in treatment-seeking among malaria, and an adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI was considered to see the strength and significance of the association. The adequacy of the final model was checked using the Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of fit test. With p- a value was 0.0830.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Science with the reference number of Ref no: CMHS/85/13/2022. Following the approval, an Official letter of cooperation was written to concerned bodies by the School of Public Health of Wollo University. Permission was also obtained from the South Gonder District health department and respective health facilities in which the data collection was conducted. Respondents were informed about the objective and purpose of the study and verbal informed consent was obtained from each respondent while permission from parents or guardians was obtained for participants of age less than 18 years also permission was taken from the participants for ages greater and equal to 18 years. Clear information was given to inform respondents about the purpose and procedure of the study, the importance of their participation, and the right to withdraw at any time if they want. Additionally, the respondents were informed about the privacy and confidentiality of the information they provided throughout the study, by maintaining anonymity and interviewing them in a separate room during the interview. All methods were carried out under relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

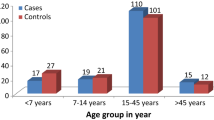

A total of 322 study participants (161 cases and 161 controls) were successfully involved in the study. Among the cases (N = 161), 58.4% were male, with 90.1% residing in rural areas. The majority belonged to the Amhara ethnicity (87%) and were married (57.8%). Regarding education, 37.9% were unable to read and write. In terms of occupation, 23.6% were students, and 21.1% were farmers. Monthly income revealed that 72% fell into the lower-income category. Family size varied, with 79.5% having five or more members. Controls (N = 161) exhibited similar trends, with 64.6% being male, 83.2% residing in rural areas, and 81.4% belonging to the Amhara ethnicity. The majority were married (59.6%), and 34.2% had a college education or above (Table 2).

Duration of treatment-seeking and Reasons for delay in treatment-seeking for malaria among cases

Out of the 161 cases, a significant majority, comprising 132 individuals (81.9%), sought medical attention at a health facility within 24 to 48 h of experiencing the initial signs and symptoms. A notable proportion (56.5%) attributed their delayed treatment seeking for malaria to challenges such as limited access to transportation and the elevated cost of medical care associated with seeking treatment at a health facility.

Knowledge about malaria

In this study, 97 (60.2%) of the controls and 71 (44%) of the cases had adequate knowledge about malaria. The majority of the cases (95%) and controls (92.5%) had heard about malaria. Most of the controls 118 (80.3%) and cases 115 (75.2%) had known mosquito bite causes malaria. The majority of the controls (66.4%) and almost half of the cases (54.2%) perceived malaria as a serious and killer disease. Almost all of the controls (95.8%) had listed two or more malaria symptoms. Most of the controls (85.8%) and half of the cases (56.7%) had known how to prevent malaria (Table 3).

Behavioural factors affecting treatment seeking for malaria

The study on behavioral factors influencing malaria treatment-seeking behavior in South Gonder District, Ethiopia (N = 322), reveals distinctive patterns among cases (N = 161) and controls (N = 161). Perception of medication side effects varied, with 60.9% of cases and 39.8% of controls expressing concerns. Health facilities were the primary choice for seeking treatment, particularly for cases (70.8%). Traditional medicines were utilized by 27.3% of cases and 25.5% of controls upon malaria symptoms onset. Moreover, self-medication was practiced by 28.6% of cases and 23.6% of controls. The decision-maker for seeking treatment predominantly was the patient, representing 62.1% of cases and 69.6% of controls(Table 4).

Physical and environmental factors affecting treatment-seeking for malaria

The study revealed that a significant proportion of controls (78.3%, 126 individuals) and a minority of cases (42.2%, 68 individuals) had easy access to transportation. Most cases (39.1%, 63 individuals) relied on walking for transportation to health facilities. Of the controls, 57.1% (92 individuals) and 36% of cases (58 individuals) reached health facilities within 30 min (Fig. 1). The majority of controls (70.2%, 113 individuals) and a few cases (46%, 74 individuals) were covered by community-based health insurance (CBHI).

Healthcare system-related factors affecting treatment seeking for malaria

The majority of controls (79.5%) and a minority of cases (39.8%) reported a very short waiting period for health services. About one-fourth of controls (24.8%) and nearly half of cases (47.2%) perceived the cost of malaria healthcare as expensive. Most controls (77%) and cases (83.2%) did not encounter shortages in drugs or laboratory services. Three-fourths of controls (78.9%) and a few cases (41.6%) expressed confidence in the health facility services they received (Table 5).

Determinant factors for delay in treatment seeking for malaria

No Multicollinearity exists among independent variables, as indicated by a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of 2.1, well below the threshold of 10.

All variables were entered into the bivariable logistic regression model. Sociodemographic variables, such as sex (p = 0.253), age group (p = 0.087), ethnicity (p = 0.171), marital status (p = 0.818), and religion (p = 0.231) were not crudely associated with delay for treatment-seeking. Other variables such as family death (p = 0.577), and taking traditional medicine (p = 0.705) were not crudely associated with delay in treatment-seeking. The bivariable logistic regression knowledge category was crudely associated with delay for treatment-seeking (COR = 1.92(1.23–2.99). All variables with p-value < 0.2 were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model.

In multivariable logistic regression, educational status, malaria drug side effects, provided health education, transportation accessibility, community-based health insurance, and confidence in malaria care were significantly associated with delays in seeking treatment for malaria.

In this study, Educational status played a crucial role, particularly for those unable to read and write, demonstrating a significantly higher delay compared to other educational categories (AOR = 3.47, p = 0.048). Students also exhibited a distinct trend towards delayed treatment (AOR = 3.34, p = 0.08). Transportation challenges significantly impacted cases, with those facing difficulties almost five times more likely to experience delays (AOR = 4.70, p = 0.02). Lack of community-based health insurance emerged as a significant factor contributing to delay among cases (AOR = 2.50, p = 0.006). Furthermore, cases lacking confidence in malaria treatment had significantly higher odds of delay compared to controls (AOR = 2.14, p = 0.032).

This study revealed that study participants who had no confidence in malaria treatment were 2.14 times more likely to delay seeking treatment for malaria [AOR = 2.14, 95% CI (1.06, 4.29)] with p-value = 0.032 (Table 6).

Discussion

The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates swift access to suitable anti-malarial treatment, preferably within the initial 24 h of fever onset, to prevent progression from uncomplicated to severe malaria7. Key findings indicate that unable to read and write, fear of malaria drug side effects, lack of health education, limited transportation, absence of community-based health insurance, and lack of confidence in health facility care contribute to treatment-seeking delays among malaria patients. This study revealed that delay in treatment-seeking among malaria patients had a significant association with educational status, malaria drug side effects, getting health education on malaria, transportation access, CBHI membership, and confidence in health malaria care. The current findings were similar to other studies conducted in North West Ethiopia that showed community-based health insurance, previous history of malaria infection, and distance were determinants of delay in seeking treatment for malaria9.

The current study showed that the educational status of the patient was found to be an important determinant factor for treatment-seeking delay among malaria patients. In this study patients who were unable to read and write were more likely to delay seeking treatment for malaria. This finding was comparable with the study conducted in Myanmar that showed patients who were unable to read and write were more likely to delay seeking treatment for malaria26, and a similar finding was reported in a study conducted in the Tigray region17. The relationship between educational level and early health-seeking might be because literate people are better able to understand health education messages delivered by different mass media and health professionals. Develop materials that can be understood if the existing health education materials are not comprehended by people with no/poor literacy—then need.

A side-effect of anti-malarial drugs was also found to be a significant factor for delays in treatment-seeking among malaria patients in health facilities. Study participants who experienced side effects of anti-malarial drugs were more likely to delay seeking treatment when they needed malaria treatment. This association might be due to the reason that most of the patients did not visit healthcare early due to fear of its side effects. A consistent finding was reported in other studies conducted in Southern Ethiopia 2.91 times and Southwest Ethiopia 4.96 times more likely to be late for the treatment of malaria care15,20. These findings contradict a study conducted in the Northwestern Zone of the Tigray region that showed side effects of anti-malarial drugs had no significant association with delay in treatment-seeking17. They may prioritize avoiding potential discomfort from medication over seeking immediate treatment for their illness.

In this study, study participants who had not received any health education regarding malaria were more likely to delay treatment-seeking for malaria. This could be due to those who did not receive health education on malaria disease as a very simple disease and also understood there was no treatment at health facilities due to a lack of knowledge on the treatment. On the other hand, individuals who had received adequate health education on malaria were found to be highly motivated to visit health facilities as early as possible due to sufficient information regarding all of the side effects and their severity. This finding was also concomitant with other study findings from North-western Ethiopia27.

The current study showed that study participants, who had no transportation access were more likely to be late in seeking treatment for malaria. This finding was comparable with other studies conducted in Uganda that showed that long distance from the place of residence to public health facilities as a result of transportation access was a notable risk factor for both delayed care seeking and severe malaria28 and a study from North West Ethiopia was also revealed study participants who traveled for more than 30 min to get to a health facility due to lack of transportation access were more likely to be late in seeking treatment for malaria9. The possible explanation for the finding is that study participants who had no transportation access may have faced difficulties in reaching healthcare facilities promptly. This could be due to limited public transportation options, lack of personal vehicles, or living in remote areas with poor road infrastructure. In addition, community-based diagnosis and treatment be considered using community malaria volunteers or community volunteer health volunteers.

This study revealed that members of the CBHI were an important determinant of delayed treatment seeking. Study participants responded that no member of CBHI was likely to delay seeking treatment for malaria. The possible explanation for this could be the shortage of money for a fee for malaria treatment. This finding was in line with a study conducted in Ghana has concluded that those who were members of health insurance schemes were less likely to delay anti-malarial treatment seeking by seeking traditional/herbal medicine and self-medication31. Furthermore, a study conducted in Ethiopia has revealed that patients who were not members of community-based health insurance (CBHI) were more likely to delay in seeking treatment when compared to those who were members of CBHI9. Confidence in the malaria care provided by health facilities was also another determinant factor of delay in treatment-seeking among malaria patients. This study revealed that study participants who had no confidence in malaria care were more likely to be late to seek treatment. The study's limitations include potential recall bias in participant responses, generalizability constraints to other settings, and reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce subjectivity.

Conclusion

In Summary, this study revealed significant associations between delays in seeking malaria treatment and factors such as educational status (those who were unable to read and write), malaria drug side effects, health education on malaria, transportation access, CBHI membership, and confidence in health malaria care. It is recommended that targeted interventions and awareness campaigns be implemented to address these determinants, promoting prompt and effective malaria treatment-seeking behavior in the studied population (Supplementary Information).

Data availability

All the necessary data are included in the manuscript. An English version data collection tool and detailed operational definitions of the outcome variable are accessible at a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency virus

- BF:

-

Blood film

- CBHI:

-

Community based health insurance

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ETB:

-

Ethiopian birr

- FMOH:

-

Federal Ministry of Health

- HIV:

-

Human immune virus

- MDG:

-

Millennium development goal

- NMCP:

-

National Malaria Control Programme

- PMI:

-

United States, President's malaria initiative

- RBM:

-

Roll back malaria

- RDT:

-

Rapid diagnostic test

- USD:

-

United States dollar

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

References

Adeyemo, A. O. et al. Malaria vaccine: The lasting solution to malaria burden in Africa. Ann. Med. Surg. 79, 104031 (2022).

Galactionova, K., Smith, T. A. & Penny, M. A. Insights from modelling malaria vaccines for policy decisions: the focus on RTS, S. Malar. J. 20(1), 1–8 (2021).

World Health Organization. Guideline Daily Iron Supplementation in Infants and Children. (World Health Organization, 2016).

Iwuafor, A. A. et al. Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of rapid diagnostic test for malaria diagnosis among febrile children in Calabar, Nigeria. Nigerian Med. J. (Journal of the Nigeria Medical Association) 59(6), 64 (2018).

World Health Organization. World malaria report. Geneva: World Health Organization. Int. J. Biostat. 6(2) (2010).

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2022. (World Health Organization, 2022).

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. (World Health Organization, 2015).

Than, M. M., Min, M. & Aung, P. L. The determinants of delayed diagnosis and treatment among malaria patients in Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. Open Public Health J. 12(1), 13 (2019).

Tiruneh, M., Gebregergs, G. B. & Birhanu, D. Determinants of delay in seeking treatment among malaria patients in Dera district, NorthWest Ethiopia: A case control study. Afr. Health Sci. 18(3), 552–559 (2018).

Chinkhumba, J. & Chibwana, A. Responses of caregivers to children under the age of five with fever and living in areas where malaria is endemic: A systematic review of qualitative studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 8(13), 520–588 (2010).

Panika, R.K. & Maohore, R.K. Assessment of Treatment Seeking Behavior of Malaria Suspected Fever Patients Attending Urban Health and Training Centre Chameli Chouk, Sagar (2019).

Solomon, A., Kahase, D. & Alemayehu, M. Trend of malaria prevalence in Wolkite health center: An implication towards the elimination of malaria in Ethiopia by 2030. Malar. J. 19(1), 1–8 (2020).

Aschale, Y. et al. Prevalence of malaria and associated risk factors among asymptomatic migrant laborers in West Armachiho District, Northwest Ethiopia. In Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine. 95–101 (2018).

Dida, N., Darega, B. & Abebe, A. Treatment-seeking behavior and associated factors among malaria suspected patients in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia: Institution-based cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. 2(1), 5 (2015).

Workineh, B. & Mekonnen, F. A. Early treatment-seeking behaviour for malaria in febrile patients in northwest Ethiopia. Malar. J. 17, 1–8 (2018).

Liyew, B. et al. Individual and community-level factors of treatment-seeking behaviour among caregivers with febrile children in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. Plos one 17(3), e0264707 (2022).

Tesfahunegn, A., Zenebe, D. & Addisu, A. Determinants of malaria treatment delay in northwestern zone of Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia, 2018. Malar. J. 18, 1–8 (2019).

Romay-Barja, M. et al. Determinants of delay in malaria care-seeking behaviour for children 15 years and under in Bata district, Equatorial Guinea. Malar. J. 15(1), 1–8 (2016).

Anyasodor, A. E. et al. Delays in seeking treatment for fever in children under five years of age in Nigeria: Evidence from the National Demographic Health Survey. Plos one 18(12), e0295772 (2023).

Getahun, A., Deribe, K. & Deribew, A. Determinants of delay in malaria treatment-seeking behaviour for under-five children in south-west Ethiopia: A case control study. Malar. J. 9(1), 1–6 (2010).

Asale, A. et al. Community based integrated vector management for malaria control: Lessons from three years’ experience (2016–2018) in Botor-Tolay district, southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 19, 1–14 (2019).

Biya, M. et al. Waiting time and its associated factors in patients presenting to outpatient departments at Public Hospitals of Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22(1), 107 (2022).

W.H. Organization. Universal Access to Malaria Diagnostic Testing: An Operational Manual (2011).

Adum, P. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of malaria preventive measures among mothers with children under five years in a rural setting of Ghana. Malar. J. 22(1), 268 (2023).

W.H. Organization. Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030. (World Health Organization, 2015).

Naing, P. A. et al. Awareness of malaria and treatment-seeking behaviour among persons with acute undifferentiated fever in the endemic regions of Myanmar. Trop. Med. Health 45, 1–10 (2017).

Paulander, J. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice about malaria in rural Tigray, Ethiopia. Glob. Health Action 2(1), 1839 (2009).

Mpimbaza, A. et al. Demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic factors leading to severe malaria and delayed care seeking in Ugandan children: A case–control study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97(5), 1513 (2017).

Hosmer Jr, D.W., Lemeshow, S. & Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression. Vol. 398. (Wiley, 2013).

Long, J.S. & Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. Vol. 7. (Stata Press, 2006).

Awuah, R. B. et al. Factors associated with treatment-seeking for malaria in urban poor communities in Accra, Ghana. Malar. J. 17(1), 1–8 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to thank Wollo University, the College of Medicine, and the Health Sciences ethical review committee. Also, we want to gratify the South Gonder District health department, study participants, and data collectors.

Funding

This investigation received no specific grant from a funding agency in the public commercial or for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AA, YW, T A, AE, NK. Investigation: AA. Methodology: AA, YW, TA, AE. Formal Analysis and software: AA, YW, T A, AE, SFF, NK. Writing-review and Editing: YW, T A, AE, SFF, NK. Writing-original draft: YW, T A, AE, SFF, NK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alga, A., Wasihun, Y., Ayele, T. et al. Factors influencing delay in malaria treatment seeking at selected public health facilities in South Gonder, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 14, 6648 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56413-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56413-7

- Springer Nature Limited