Abstract

In this study, we estimated the excess mortality from all-causes of death and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in adults living in the state of São Paulo during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Number of deaths were retrieved from the Mortality Information System before (2017–2019) and during (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic, considering the following underlying causes of death: Neoplasms; Diabetes Mellitus; Circulatory System Diseases, and Respiratory System Diseases. Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) were calculated by dividing the mortality rates in 2020 by average mortality rates in 2017–2019, according to sex, age group, geographic location (state, capital, and Regional Health Departments). In 2020, occurred 341,704 deaths in the state of São Paulo vs 290,679 deaths in 2017–2019, representing an 18% increase in all-cause mortality (SMR 1.18) or 51,025 excess deaths during the first year of COVID-19 pandemic. The excess mortality was higher in men (186,741 deaths in 2020 vs 156,371 deaths in 2017–2019; SMR 1.18; 30,370 excess deaths) compared to women (154,963 deaths in 2020 vs 134,308 deaths in 2017–2019; SMR 1.15; 20,655 excess deaths). Regarding NCDs mortality, we observed a reduction in cancer mortality (SMR 0.98; −1,354 deaths), diseases of the circulatory system (SMR 0.95; −4,277 deaths), and respiratory system (SMR 0.88; −1,945). We found a 26% increase in Diabetes Mellitus mortality (SMR 1.26; 2885 deaths) during the pandemic year. Our findings corroborate the need to create and strengthen policies aimed at the prevention and control of NCDs, in order to mitigate the impact of future infectious disease pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs) constitute the largest burden of morbidity and mortality in the world, accounting for, approximately, 70% of all annual deaths. In Brazil, NCDs account for 74% or 975,400 deaths per year. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading causes of NCDs deaths, followed by cancer, respiratory diseases and diabetes mellitus1,2. In addition to NCDs, the COVID-19 pandemic presented itself as one of the greatest health challenges on a global scale of the twenty-first century3, particularly considering that people living with NCDs had a higher risk of developing severe COVID-19 conditions, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)4. Because of the synergism of these two epidemics to produce morbidity and mortality, some have argued that a syndemic approach is needed to better understand and protect the health of our communities5,6.

Social distancing and social restriction measures were adopted to reduce the spread of the coronavirus, but these preventive measures may have caused adverse consequences, such as changes in people’s lifestyles, as observed in Brazil7,8 and other countries9,10. In addition, it may have caused a reduction and/or temporary suspension of health procedures, actions, and services, as well as an increased demand for hospital care due to COVID-19. The reallocation of health resources to cope with COVID-19 presented an additional challenge in maintaining the necessary health care for people living with NCDs11. In May 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a survey evaluating the provision of services for NCDs during the COVID-19 pandemic, identifying that 75% of participating countries reported interruptions in NCDs services12. In the Americas, the main reasons for the reduction and/or interruption of NCDs services included the cancellation of elective care services, healthcare teams being relocated to respond to COVID-19 and the patients’ non-attendance to in-person appointments13. In the state of São Paulo, the Resolution SS-28 of March 17, 2020 foresee the possibility of canceling and suspending various activities, such as outpatient consultations, diagnostic tests, surgical procedures, and elective surgeries. The document recommended the maintenance of these activities only when the benefits of prompt completion outweigh the risks associated with the COVID-19, especially for at-risk patients (adults over 60 years of age, patients with “comorbidities,” and immunosuppressed)14.

The overlap of COVID-19 and NCDs in space and time constituted an additional challenge within the scope of health services and the Brazilian Unified Health System15. Considering millions of people living with NCDs, deaths related to NCDs complications in patients not infected by the new coronavirus could eventually become more severe and significant than deaths directly affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection16. Epidemiological studies quantifying the potential the impact of COVID-19 on morbidity and mortality may provide important information to guide the planning of actions and public policies17. Excess all-cause and NCDs mortality have been used as a proxy of the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population health from different countries and socioeconomic groups18,19,20.

In this study, we estimated the excess all-cause and NCDs mortality in adults living in the state of São Paulo during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Excess deaths were estimated using all deaths in 2020 by NCDs (cancer, diabetes mellitus, diseases of the circulatory system, and diseases of the respiratory system), sex, age group, geographic location (state, capital, and regional health departments) and month of the year.

Methods

Epidemiological study carried out based on secondary data including all deaths in adults (≥ 18 years) residing in the state of São Paulo from the months of January to December, of the years 2017–2019 and 2020. Data on mortality were retrieved from the Mortality Information System of the state of São Paulo, obtained via the TabNet system of the State Department of Health of São Paulo. We conducted a comparative analysis of all-cause and NCDs deaths in the state of São Paulo before (2017–2019) and during (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic. The underlying causes of death were collected according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) and the goals of the Brazilian Strategic Action Plan to Cope with NCDs in Brazil 2021–203021: all-causes of death, cancer (C00-C97), diabetes mellitus (E10-E14), diseases of the circulatory system (I00-I99), and diseases of the respiratory system (J30-J98). Of note, São Paulo has one of the best quality Mortality Information System in Brazil, with less than 5% of unknow/not classified underlying causes of death21. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (EPM/UNIFESP), approved under the CAAE No. 4,637,943 of April 8, 2021. All research methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. The need for informed consent was waived by the approving Ethical Committee of the Federal University of Sao Paulo (EPM/UNIFESP) due to retrospective nature of the study. .

Data analysis was carried out from the construction of three databases on the deaths of residents for the state of São Paulo, for the capital, and for Regional Health Departments (Departamentos Regionais de Saúde—DRS). The administrative division of the São Paulo State Department of Health (SES/SP) takes place through the DRS22 that divided the state into 17 departments (I. Grande São Paulo, II. Araçatuba, III. Araraquara, IV. Baixada Santista, V. Barretos, VI. Bauru, VII. Campinas, VIII. Franca, IX. Marília, X. Piracicaba, XI. Presidente Prudente, XII. Registro, XIII. Ribeirão Preto, XIV. São João da Boa Vista, XV. São José do Rio Preto, XVI. Sorocaba, and XVII. Taubaté) responsible for coordinating regional activities14. Deaths in the DRS were analyzed annually in the previous period (2017–2019) and during the pandemic (2020), in the seventeen DRS of the state, analyzing all-causes of death and NCDs deaths by sex and age groups (15–19 years, 20–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years, 80 and over). Deaths in the state and capital were analyzed monthly in the pre-pandemic period (2017–2019) and in the pandemic period (2020) for all-causes and NCDs deaths by sex and age groups.

Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) was calculated by dividing the mortality rates in 2020 by the number of deaths expected for that year, the latter being calculated from the average number of deaths and population size in the triennium that preceded the COVID-19 pandemic (2017–2019). Excess deaths were calculated by subtracting the observed number of deaths minus the expected number of deaths in 2020, being the latter calculated as the average mortality rates in 2017–2019 times the population projected for 2020 in the state. Population data by year and by municipality were obtained from population projections available on the DATASUS TabNet (Department of Informatics of SUS). The mortality rate per 100,000 inhabitants was calculated according to the underlying cause of death by ICD-10, considering in the analyses the sociodemographic characteristics of the population of the state of São Paulo.

Data analysis was performed using the Excel 2016 software and Qgis 3.28 Software. The classes of the SMR intervals presented in the maps were defined using the mode of natural breaks, also known as Jenks Criterion, which considered the automatic distribution of the values of each interval seeking to minimize the variance within each class, increasing the variance between the different classes23.

Results

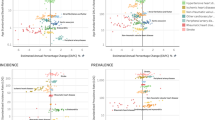

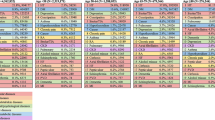

In 2020, occurred 341,704 deaths in the state of São Paulo vs 290,679 deaths in 2017–2019, representing an 18% increased all-cause mortality (SMR 1.18) or 51,025 excess deaths during the first year of COVID-19 pandemic. The excess mortality was higher in men (186,741 deaths in 2020 vs 156,371 in 2017–2019; SMR 1.18; 30,370 excess deaths) compared to women (154,963 deaths in 2020 vs 134,308 in 2017–2019; SMR 1.15; 20,655 excess deaths). Regarding NCDs mortality, we observed a reduction in the number of deaths from cancer (SMR 0.98; −1,354 deaths), diseases of the circulatory system (SMR 0.95%; −4277 deaths), and respiratory system (SMR 0.88; −1945), and an increase in the number of deaths from Diabetes Mellitus (SMR 1.26; 2885 deaths) during the pandemic year. Overall, the number of NCDs deaths in men decreased from 89,914 deaths in 2017–2019 to 87,194 deaths in 2020, whereas in women these figures were 82,308 deaths in 2017–2019 to 80,337deaths in 2020 (Table 1). Figure 1 displays the monthly SMR and excess deaths from all-causes and NCDs deaths in the State of Sao Paulo.

In the city of São Paulo, the average annual deaths in 2017–2019 were 38,354 in men and 36,538 in women. In 2020, 47,398 deaths occurred in men and 42,799 in women, representing an increase of 23.6% in the number of deaths in men and 17.1% in women (Table 1). Regarding the NCDs deaths, we observed a reduction in the number of deaths from cancer (−10.7%), diseases of the circulatory system (−13.3%), and of respiratory system (−29.2%). On the other hand, we observed an increase in the number of deaths from Diabetes Mellitus (5.4%), with an excess of 81 deaths in men and 61 in women (SMR of 1.06 and 1.04, respectively).

Regarding the age groups, Table 2 shows that the lowest SMR occurred in the age group of 15 to 19 years, with 0.92 for men in the state and in the municipality, and 1.01 in the state and 1.12 in the municipality for women. In women, SMR in the age group of ≥ 80 years was the second lowest, both in the state and in the municipality (1.11 and 1.17, respectively), being only higher than the age group of 15 to 19 years. In men, the age group ≥ 80 years presented SMR of 1.19 in the state and 1.22 in the municipality.

Figure 2 represents the SMR and excess deaths for each grouping of NCDs in the Regional Health Departments of the state of São Paulo. Two regions had SMR higher than 1.00 for cancer mortality, São José do Rio Preto (1.01) and Sorocaba (1.04), presenting excess of 28 and 115 deaths, respectively. In regard to mortality due to diabetes mellitus, all regionals had SMR greater than 1.00, with the Regional of Barretos (SMR 1.59) having the highest excess of deaths (67 deaths), followed by the Regional of Piracicaba (SMR 1.39), with an excess of 164 deaths, and the Regional of São João da Boa Vista (SMR 1.32), which had an excess of 111 deaths. Regarding mortality from diseases of the circulatory system, three regions had SMR greater than 1.00: Marília (1.06), Registro (1.04), and Aracatuba (1.03), with excess deaths of 144, 27, and 42, respectively. None of the regions had SMR for diseases of the respiratory system equal to or greater than 1.00; no excess deaths were identified within this group of NCDs in the state.

Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) by noncommunicable diseases and by Regional Health Departments of the state of São Paulo. São Paulo, 2020. The maps were generated in Qgis 3.28 Software—https://www.qgis.org/pt_BR/site/index.html.

Discussion

Our study estimated an increase in overall mortality during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) compared with the previous three-year period (2017–2019) in adults living in the state of São Paulo. In the same period, there was a reduction in mortality from cancer, diseases of the circulatory and respiratory system, and an increase in the number of deaths from diabetes mellitus. Similar results were observed for the city of São Paulo and the 17 DRSs, particularly those placed in the northern region of Sao Paulo. Although we have not explored the predictors of regional differences, future studies may be important to better understand the explanation for this pattern.

Several studies, both at the national and international levels, have estimated excess mortality from all-cause and cause-specific mortality since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. A study with 22 countries worldwide, including Brazil, indicated excess all-cause mortality based on the five years prior to the pandemic. It was identified that Brazil (SMR: 1.13; excess of 120,220 deaths), France (SMR: 1.03; excess of 13,700 deaths), Italy (SMR: 1.03; excess of 11,103 deaths), Spain (SMR: 1.17; excess of 48,643 deaths), the United Kingdom (England [SMR: 1.15; excess of 53,869 deaths], Wales [SMR: 1.15; excess of 53,869 deaths], Northern Ireland [SMR: 1.08; excess of 825 deaths], and Scotland [SMR: 1.10; excess of 3911 deaths]), and the United States (SMR:1.2; excess of 231,327 deaths) had excess mortality from all-cause, while Australia (SMR: 0.97; −2083 deaths), Denmark (SMR: 0.96; −1339 deaths), and Georgia (SMR: 0.97; −839 deaths) showed a decrease in the number of deaths. These findings were correlated with geographic location and seasonality, as well as governments’ swiftness in applying preventive measures to reduce the spread of the COVID-1924. Another modelling study in Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) suggested that 15,000 to 20,000 excess deaths occurred during 2020–202125.

Studies analyzing the excess mortality have gained temporal continuity, with the extension of the analyses of this pandemic effect also for the years 2021 and 2022. A study showed that the US continued with excess mortality from all-causes of death compared to similar countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Austria during the year 2021 and early 2022; a difference that is responsible for 150,000 to 470,000 deaths, which was mitigated in the 10 states with the highest vaccination coverage in the country26. While some national and international studies associate excess all-cause mortality with COVID-19 mortality27,28,29, others call attention to a low percentage of excess deaths confirmed by COVID-19, suggesting that many deaths from the disease may not have been documented, as was the case in Ecuador for the year 2020, in which only 20% of excess deaths were confirmed as being caused by the new coronavirus30.

Regarding the underlying cause of deaths, our study identified a reduction in the number of deaths from cancer (−2.0%, SMR = 0.96 in women and 0.99 in men) and diseases of the circulatory system (−4.8%, SMR = 0.95) in the state of São Paulo. In Brazil, a previous study has also estimated the reduction in the number of NCDs deaths during the pandemic period. Their study showed that the number of cancer deaths in Brazil in 2020 was 10% lower than expected, based on the mortality profile in the same period in 2019 for the country (SMR = 0.90; 95%CI 0.90–0.91). Similar findings were observed for cardiovascular diseases (SMR = 0.91; 95%CI 0.91–0.920). A possible explanation for these findings is the overlap of COVID-19 as a competitive cause of death, which may have resulted in migration of cause of death. In fact, previous studies have reported an increased number of reports of cancer and cardiovascular diseases as “comorbidities” in death certificates31. Therefore, prevalent cases of cancer and diseases of the circulatory system, which would have a higher risk of death from these diseases, may have had their deaths anticipated due to COVID-1931,32.

Modelling studies have estimated the future impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality due to delay in cancer diagnosis. Research in countries such as the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and India points to estimates of additional deaths/excess mortality from different types of cancer in the coming post-pandemic years33,34,35. In France, an excess of 1,000 to 6,000 deaths was estimated in the coming years33, while in the United Kingdom the proportion of additional cancer deaths was estimated in the coming years, being identified between 15.3 and 16.6% of additional deaths due to colorectal cancer, 7.9% to 9.6% due to breast cancer, 5.8% to 6.0% due to esophageal cancer, and 4.8% to 5.3% due to lung cancer35. In Australia, the impact of additional deaths caused by changes in the histological stage of cancer at the beginning of treatment was predicted for breast, lung, colorectal and melanoma cancers, whose evolutionary stages may be more advanced, which will also cause problems related to higher health costs34.

A Brazilian study pointed out a reduction in the number of hospital deaths due to diseases of the circulatory system in 2020, represented by 1,495 fewer deaths than expected. However, this same study pointed out that the Midwest region showed a 15.1% increase in the number of deaths from diseases of the circulatory system, and that ten Federation Units also had a higher number of deaths in 2020, not including the state of São Paulo36, a finding that is in line with our findings. However, it is worth mentioning that one of the impact points of COVID-19 may be related to changes in the place of occurrence of deaths, including the increase in home deaths due to limited access to services from the overload of health services, and isolation and social restriction measures that hindered the early detection of cardiovascular symptoms and immediate treatment18.

Regarding mortality from diabetes mellitus, this study indicated an increase in the number of deaths (25.6%) with an excess of 1,532 deaths in men and 1,353 deaths in women in 2020 (SMR of 1.29 and 1.22, respectively). These findings are in line with an American study that pointed out that an increase in diabetes mortality was observed in most American states, associated with the pandemic in general (relative change in mortality rates 1.19 [95%CI 1.13, 1.25]) and in 24 states, with the highest proportion of relative change in mortality rates in Mississippi (1.46 [95%CI 1.23, 1.72]), followed by New Jersey (1.44 [95%CI 1.08, 1.91]) suggesting indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the comprehensive health care of people living with diabetes mellitus37. Among the possible explanations for the increase in mortality from diabetes mellitus during the COVID-19 pandemic are: hesitation of patients with severe symptoms of the disease to receive hospital medical services during the most severe phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, with the concern of in-hospital infection by the new coronavirus; occurrence of early hospital discharge of patients with diabetes mellitus, since the pandemic overwhelmed health services, especially hospital care37; restrictions on outpatient care for diabetes and possible delays in emergency services38 and a possible reduction in the quality of management for patients with diabetes mellitus in the context of the pandemic, capable of increasing mortality of the disease in the absence of timely treatment37,38,39.

A Brazilian study carried out in 171 municipalities in the state of São Paulo identified that most municipalities (89.6%) defined a set of health services to be maintained during the pandemic, with 95.7% reporting discontinuities in health care for people living with NCDs. Among the services with discontinuity (total interruption and partial interruption) were elective surgeries (54.1% and 38.1%), rehabilitation (10.0% and 62.1%), diagnosis/treatment of NCDs (1.0% and 42.1%), diagnosis/treatment of cancer (partial interruption 15.9%), and palliative care (4.4% and 22.6%)40. Of note, diabetes mellitus requires the use of medications, continuous monitoring, and comprehensive care at different levels to prevent complications that can increase mortality from the disease. Therefore, the need for isolation, the difficulty of using transport and the risk of people living with diabetes mellitus developing the most severe form of COVID-19 may have created the false impression that avoiding COVID-19 was more urgent than controlling the complications resulting from the decompensation of diabetes41.

Regarding the findings on the reduction of mortality from diseases of the respiratory and circulatory system in São Paulo, they corroborate with national research, which observed reductions in deaths from these two groups of diseases in Brazil in 202042. The fact that there were no excess deaths due to diseases of the respiratory system in São Paulo may corroborate the idea that many deaths due to respiratory causes were reported as COVID-19 deaths, which started to compose a new special chapter in the Mortality Information System.

This study has some limitations. During data collection, a small divergence (< 2%) was observed between the number of deaths in the state and the sum of the number of deaths obtained across DRS, due to missing values in the “municipality of residence” in the state of São Paulo. We have considered the average of deaths and population size between 2017–2018 to estimate the expected number of deaths in 2020, had the Covid-19 not occurred. Although similar methods have been applied elsewhere43, we recognize the expected number of deaths could have been different, considering temporal trends in cause-specific NCD mortality. However, our findings may provide a comprehensive and useful information on excess mortality in the state of São Paulo during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of note, São Paulo has one of the highest quality mortality information systems in the country, with less than 5% of unknow/not classified underlying causes of death.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we estimated a 18% increased all-cause mortality (SMR 1.18) or 51,025 excess deaths during the first year of COVID-19 pandemic compared to 2017–2019. In the same period, however, there was a reduction in mortality from cancer, circulatory system disease, respiratory disease, and increased mortality from diabetes mellitus. Our findings reinforce the importance of formulating and implementing public policies that guarantee the prevention and control of NCDs. These measures are imperative to mitigate the detrimental health effect on the health of people living with NCDs, particularly in situations of health emergency, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. Noncommunicable diseases: progress monitor 2022. (2022).

WHO. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. 223 p. (World Health Organization, 2018).

Werneck, G. L. & Carvalho, M. S. Vol. 36 e00068820 (SciELO Public Health, 2020).

Yang, J. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 94, 91–95 (2020).

Horton, R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. The Lancet 396, 874. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6 (2020).

Sheldon, T. A. & Wright, J. Twin epidemics of covid-19 and non-communicable disease. Bmj 369, m2618. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2618 (2020).

Malta, D. C. et al. Doenças crônicas não transmissíveis e mudanças nos estilos de vida durante a pandemia de COVID-19 no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 24 (2021).

Malta, D. C. et al. A pandemia da COVID-19 e as mudanças no estilo de vida dos brasileiros adultos: um estudo transversal, 2020. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 29, e2020407 (2020).

Stanton, R. et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 4065 (2020).

van Zyl-Smit, R. N., Richards, G. & Leone, F. T. Tobacco smoking and COVID-19 infection. The Lancet Respirat. Med. 8, 664–665 (2020).

Chan, E. Y. Y. et al. What happened to people with non-communicable diseases during COVID-19: implications of H-EDRM policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 5588 (2020).

WHO. Rapid assessment of service delivery for NCDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: World Health Organ. (2020).

Organization, P. A. H. (Pan American Health Organization Washington, 2020).

Saúde, S. d. E. d. Secretaria de Estado de Saúde de São Paulo (SES/SP). Coordenadoria de Gestão Orçamentária e Financeira. Diário Oficial. Resolução SS - 28, de 17–3–2020. . Nº 54 24p (2020).

Oliveira, W. K. d., Duarte, E., França, G. V. A. d. & Garcia, L. P. Como o Brasil pode deter a COVID-19. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 29 (2020).

Modesti, P. A. et al. Indirect implications of COVID-19 prevention strategies on non-communicable diseases: an Opinion Paper of the European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Hypertension and Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Subjects Living in or Emigrating from Low Resource Settings. BMC Med. 18, 1–16 (2020).

Machado, C. J. et al. Estimativas de impacto da COVID-19 na mortalidade de idosos institucionalizados no Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 25, 3437–3444 (2020).

Brant, L. C. C. et al. Excess of cardiovascular deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazilian capital cities. Heart 106, 1898–1905 (2020).

Faust, J. S. et al. All-cause excess mortality and COVID-19–related mortality among US adults aged 25–44 years, March-July 2020. Jama 325, 785–787 (2021).

Leon, D. A. et al. COVID-19: a need for real-time monitoring of weekly excess deaths. The Lancet 395, e81 (2020).

Transmissíveis, S. et al. Plano de Ações Estratégicas para o Enfrentamento das Doenças Crônicas e Agravos não Transmissíveis no Brasil 2021–2030. (2021).

Legislativa., G. d. S. P. A. Cria unidade na Coordenadoria de Regiões de Saúde, da Secretaria da Saúde, altera a denominação e dispõe sobre a reorganização das Direções Regionais de Saúde. . (2012).

Carvalho, P. F. B. Classificação de dados geográficos e representação cartográfica: discussões metodológicas. Revista Geografias 26, 91–111 (2018).

Achilleos, S. et al. Excess all-cause mortality and COVID-19-related mortality: a temporal analysis in 22 countries, from January until August 2020. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51, 35–53 (2022).

Kepp, K. P. et al. Estimates of excess mortality for the five Nordic countries during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020–2021. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51, 1722–1732 (2022).

Bilinski, A., Thompson, K. & Emanuel, E. COVID-19 and excess all-cause mortality in the US and 20 comparison countries, June 2021-March 2022. JAMA 329, 92–94 (2023).

Aburto, J. M. et al. Estimating the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality, life expectancy and lifespan inequality in England and Wales: a population-level analysis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 75, 735–740 (2021).

Silva, G. A., Jardim, B. C. & Santos, C. V. B. d. Excesso de mortalidade no Brasil em tempos de COVID-19. Ciencia & saude coletiva 25, 3345–3354 (2020).

Woolf, S. H. et al. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March-July 2020. Jama 324, 1562–1564 (2020).

Cuéllar, L. et al. Excess deaths reveal the true spatial, temporal and demographic impact of COVID-19 on mortality in Ecuador. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51, 54–62 (2022).

Jardim, B. C., Migowski, A. & Corrêa, F. d. M. Covid-19 in Brazil in 2020: impact on deaths from cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Revista de Saúde Pública 56, 22 (2022).

Evaluations., I. f. H. M. a. Estimation of total mortality due to COVID-19. (2021).

Blay, J. et al. Delayed care for patients with newly diagnosed cancer due to COVID-19 and estimated impact on cancer mortality in France. ESMO Open 6, 100134 (2021).

Degeling, K. et al. An inverse stage-shift model to estimate the excess mortality and health economic impact of delayed access to cancer services due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia-Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13505 (2021).

Maringe, C. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. The Lancet Oncol. 21, 1023–1034 (2020).

Armstrong, A. d. C. et al. Excesso de Mortalidade Hospitalar por Doenças Cardiovasculares no Brasil Durante o Primeiro Ano da Pandemia de COVID-19. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 119, 37–45 (2022).

Ran, J. et al. Increase in Diabetes Mortality Associated With COVID-19 Pandemic in the U.S. Diabetes Care 44, e146-e147, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-0213 (2021).

Bonora, B. M., Morieri, M. L., Avogaro, A. & Fadini, G. P. The toll of lockdown against COVID-19 on diabetes outpatient care: analysis from an outbreak area in Northeast Italy. Diabetes Care 44, e18–e21. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1872 (2021).

Caruso, P. et al. Diabetic foot problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary care center: the emergency among the emergencies. Diabetes Care 43, e123–e124. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1347 (2020).

Duarte, L. S., Shirassu, M. M., Atobe, J. H., Moraes, M. A. d. & Bernal, R. T. I. Continuidade da atenção às doenças crônicas no estado de São Paulo durante a pandemia de Covid-19. Saúde em Debate 45, 68–81 (2022).

SIS/Saúde., S. F. I. Diabetes avançou silenciosamente na pandemia. (Dez 2021.).

Santos, A. M. d. et al. Excess deaths from all causes and by COVID-19 in Brazil in 2020. Revista de Saúde Pública 55, 71, https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055004137 (2021).

Fernandes, G. A. et al. Excess mortality by specific causes of deaths in the city of São Paulo, Brazil, during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 16(6), e0252238 (2021).

Funding

The research was carried out with the financial support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES)—Financing Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.R. and L.F.M.R. conceived, designed, and helped to write and revise the manuscript; B.R. and L.F.M.R. were responsible for coordinating the study, contributed to the intellectual content, and revise the manuscript; B.R., G.F., R.M.D. and L.F.M.R. interpreted the data, helped to write and revise the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study design, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Resende, B.d., Dias, R.M., Ferrari, G. et al. Excess mortality in adults from Sao Paulo during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: analyses of all-cause and noncommunicable diseases mortality. Sci Rep 13, 23006 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50388-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50388-7

- Springer Nature Limited