Abstract

To analyse mortality associated to emergency admissions on weekends, differentiating whether the patients were admitted to the Internal Medicine department or to the hospital as a whole. Retrospective follow-up study of patients discharged between 2015 and 2019 in: (a) the Internal Medicine department (n = 7656) and (b) the hospital as a whole (n = 83,146). Logistic regression models were fitted to analyse the risk of death, adjusting for age, sex, severity, Charlson index, sepsis, pneumonia, heart failure and day of admission. Cox models were also adjusted for the time from admission until normal inpatient care. There was a significant increase in mortality for patients admitted in weekends with short stays in Internal Medicine (48, 72 and 96 h: OR = 2.50, 1.89 and 1.62, respectively), and hospital-wide (OR = 2.02, 1.41 and 1.13, respectively). The highest risk in weekends occurred on Fridays (stays ≤ 48 h: OR = 3.92 [95% CI 2.06–7.48]), being no significative on Sundays. The risk increased with the time elapsed from admission until the inpatient department took over care (OR = 5.51 [95% CI 1.42–21.40] when this time reached 4 days). In Cox models patients reached HR = 2.74 (1.00–7.54) when the delay was 4 days. Whether it was Internal Medicine or hospital-wide patients, the risk of death associated with emergency admission in WE increased with the time between admission and transfer of care to the inpatient department; consequently, Friday was the day with the highest risk while Sunday lacked a weekend effect. Healthcare systems should correct this serious problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the late 1980s, suspicions of increased mortality associated with non-working days have been raised and have given rise to the disturbing concept of "weekend effect"1. Numerous studies have subsequently shown that differences in patient care during the weekend may have consequences for their health status.

Thus, it has been shown that this difference in care not only affects the weekend, but patients admitted during holiday periods also have increased mortality2. There is some research on this problem in Spain3,4,5,6, although most of the publications on this issue have taken place in the Europe7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and North America14,15,16,17,18, and more recently Asia19. Furthermore, most of the studies on the "weekend effect" focus on specific diseases or health problems11,19,20,21,22 and there are almost no publications on regular patients in Internal Medicine services, in which most of patients suffer from multi-pathological problems and with heterogeneous causes of admission4.

Some studies have found that mortality differences observed in patients admitted on weekends are greater in the short term, and as length of stay increases, this "weekend effect" fades3,4,23,24,25. Decreased staffing levels26,27,28, increased severity of illness or delayed procedures29,30,31 have been associated with this increased mortality.

Although most authors agree on the negative impact of this phenomenon, the debate continues, as not all researchers agree that these differences are relevant6,32,33,34. There is little evidence in the field of Internal Medicine, whose patients are highly complex, with pluri-pathological and comorbid problems. Often, emergency physicians do not have the time to comprehensively address the Internal Medicine patient. For this reason we want to discover if admission on the weekend and holidays implies greater mortality according to whether the patients are admitted to the Internal Medicine department or to the hospital as a whole, analysing the length of stay, the severity of illness, and the time from admission to normal inpatient care.

Methods

Design and setting

Retrospective follow-up study of patients over 14 years of age admitted to the emergency department of the Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de La Candelaria (HUNSC) until their discharge or death, between 2015 and 2019 (n = 83,146); they were not patients scheduled for admission but unplanned emergency admissions. This is a tertiary care hospital with 960 beds, located in Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. It serves a population of about 500,000 inhabitants, from which patients are referred to lower-level hospitals, which were excluded as it was not known for sure when death occurred.

Staffing

The usual medical care of patients admitted to the HUNSC was provided in the morning on working days, with the on-call medical team overseeing emergency care during the evening and night hours, as well as on non-working days. The admission of a patient was decided by a specialist from the department, who must carry out the complete diagnostic and therapeutic procedure even if his or her working hours had ended. When the specialist anticipated that the procedure will require a long time, the evaluation and admission of the patient could be transferred to the on-call team. The medical team on duty in the medical area was in charge of attending to the incidents of patients admitted to the Internal Medicine, Geriatrics, Digestive, Endocrinology, Rheumatology, and Medical Oncology services, as well as admitting patients from these specialities; in the event of multi-pathological medical complications occurring in patients admitted to other specialities, assistance was also provided. The on-call team consisted of 2 specialist physicians and 3 physicians in training throughout the year, except for occasional times of high pressure of care when the number of professionals was exceptionally increased. One of the doctors in training of this on-call team addressed questions/emergencies from the patients already admitted, so the rest of the team was not distracted from the formal emergency room (ER). Nursing staff assigned to the ER during on-call did not undergo changes in WD or WE. Patients admitted to the medical specialties were immediately transferred from the ER to the beds in each department; only patients admitted in MI had to routinely wait, occupying ER beds, until the MI department had beds to which they could be transferred. A longer explanation of how our hospital operates is included as text in the supplemental file.

Data extraction

Hospital data were obtained from the minimum basic data set (MBDS) of the Spanish Government for hospital discharges in Spain35, for the period 2015–2019. Approval of the study was given by the Bioethics Committee of the Nª Sra. de Candelaria University Hospital, with the code CHUNSC_2018_47 and the need for informed consent was waived by the ethical committee of this hospital. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations." The database for this study was produced by the Ministry of Health with aggregated fully anonymized data, so individual written consent by patients is not required in Spain for the use of the BMDS (under the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 on the protection of personal data and digital rights, which transcribe the European Union General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679).

The data recorded in this registry were obtained excluding patients transferred from other services and hospitals. In addition, for patients admitted to the Internal Medicine department (n = 7656), comorbidity information was extracted on the existence of sepsis, congestive heart failure or pneumonia at the time of admission, and the Charlson index was calculated36. For the analysis of the group of patients admitted to Internal Medicine, we excluded those who were moved to the palliative care unit, and also the patients admitted to critical services. For patients admitted in the hospital as a whole, only data from the MBDS (age, sex, year of admission, and working day or holiday) were available; to approximate this group comorbidities, we used the “All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups” (APR-DRG) severity subclasses, which is a validated classification of patients into four levels according to their reason of admission37.

Definitions

Working days (WD) were considered Monday (from 8:00 h), to Friday (up to 15:00 h); patients admitted from Monday to Thursday from 15:00 were transferred daily at 8:00 the next day. Weekends (WE) were defined as Fridays (from 15:01 h), Saturdays, and Sundays (until Monday 7:59), in addition to public holidays, and also the eve of public holidays from 15:01 h. Mortality was calculated and analysed according to: (a) whether the admission occurred on WD or WE; (b) whether it occurred on Friday, Saturday or Sunday; and (c) the time it took for the patients to be attended by the physicians of the department where they were admitted. This time was estimated as the number of days elapsed between the time of admission by the physicians on duty and the transfer of responsibility for care, at the end of the WE, to the physicians of the department where the patient was admitted. The follow-up time for each patient was from admission until hospital discharge or death, since the primary outcome of the study was hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were summarised with absolute and relative frequencies (%), and continuous variables with the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Bivariate analysis between qualitative variables was performed using Pearson's Chi-square test and between quantitative variables using Student's t-test. The non parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used when the variables did not approximate the normal distribution.

For the analysis of mortality, logistic regression models (summarised with the OR and its 95% CI) were fitted taking as dependent variable the outcome of death or not, and as independent variables all those mentioned above (age, sex, Charlson index, diagnosis at admission of pneumonia, congestive heart failure, sepsis, year of admission, severity on admission, and WE or WD); Since the length of stay was identified as a confounding variable, associated to the studied exposure and effect (Supplementary Table 1), it was stratified and a model was fitted for each level of this variable (≤ 48, ≤ 72, ≤ 96 and > 96 h). Also Cox proportional risk models, summarised with HR (95% CI), were adjusted including the same independent variables plus the time elapsed (days) until the patient was assessed by the physicians of the department where he/she was admitted, and with death as the dependent variable. Analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical package (version 26, in Spanish) always using bilateral hypotheses.

Results

A total of 7656 admissions to Internal Medicine were analysed, of which 4296 were admitted on weekdays WD and 3360 on WE. Mean age was similar in both groups (70 years in WD and WE; P > 0.05). There were also no differences in sex distribution (WD 53% male vs WE 54%; P > 0.05), number of comorbidities (WD 2.64 vs. WE 2.53; P > 0.05), or in diagnoses of heart failure, respiratory infection or sepsis, nor in mortality; short stays were significantly more frequent among patients admitted on WD, and there were differences in the distribution of admissions in the different years studied (Table 1). For patients in the hospital as a whole, 83,146 admissions were analysed, of which 48,271 were admitted on WD and 34,875 on WE; also in these patients short stays were significantly more frequent on WD and there were also differences in the distribution of admissions in the different years studied (Table 1). Friday was the day with the highest number of admissions for Internal Medicine while for the hospital as a whole it was Wednesday, with Saturdays and Sundays being the days with the fewest admissions in both groups of patients (Supplementary Table 2). The 10 most common diagnoses for WD and WE emergency admissions are shown in the supplementary Table 3, with no important frequency differences; among them, the highest mortality rate was for pneumonitis due to food inhalation and vomiting, above 20% in WD and WE.

Stratification of the bivariate analyses according to length of stay (Supplementary Table 4) corroborated the absence of significant differences between WD and WE for Internal Medicine patients except for mortality, which was significantly higher in WE when stays were up to 48 h (p < 0.001), 72 h (p < 0.01) and 96 h (p < 0.05). For the hospital-wide patient group, these differences in mortality were only significantly higher (p < 0.01) when their stays did not exceed 48 h.

Multivariate analysis (Table 2) corroborated the significant association of mortality with admissions in WE, both in Internal Medicine patients and in the hospital as a whole. This association was stronger the shorter the length of stay, from an OR = 2.50 (95% CI 1.60–3.90) in Internal Medicine for stays of up to 48 h to an OR = 1.62 (95% CI 1.18–2.21) for stays of up to 96 h and losing significance for longer stays. This pattern was repeated for the hospital-wide group (Table 2) with an OR = 2.02 (95% CI 1.66–2.47) for stays up to 48 h and OR = 1.41 (95% CI 1.20–1.65) for stays up to 72 h.

When the risk of death associated with admission on each day of the weekend was analysed separately (Table 3), we found that Internal Medicine patients admitted on Fridays and with stays of up to 48 h had an OR = 3.92 (95% CI 2.06–7.48) which decreased on Saturdays to OR = 2.38 (95% CI 1.14–4.99) and was not significant on Sundays (OR = 1.98; 95% CI 0.96–4.09). The same was true for patients in the whole hospital, where the risk of death was diluted from Friday to Sunday; also, the risk associated with admission on each day decreased with increasing length of stay (Table 4).

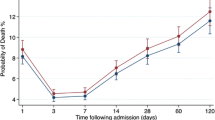

Table 4 presents the logistic analyses in which the day of admission was not included but instead the time it took for patients to be seen by the physicians in the department to which they were admitted. It shows that Internal Medicine patients with stays of up to 48 h suffered significant increases in the risk of death when the delay reached 2 days (OR = 2.40; 1.24–4.65) and reached risks of 5.51 (1.42–21.40) when the delay was 4 days; again, the risk associated with each day of delay decreased with increasing length of stay. The same pattern held for hospital-wide patients, who reached risks of 2.94 (1.58–5.48) for 4-day delays and 96-h stays. Supplementary Table 5 shows that there was no relevant change when the logistic adjustment for all hospital patients was repeated after excluding admissions for delivery and caesarean section (n = 14,208); this analysis was also repeated by adjusting Cox proportional risk models (supplementary Table 6) to corroborate the increase of the risk of death in a dose–response manner, reaching HR = 2.03 (1.16–3.55) when the delay was 2 days in IM patients with stays of up to 48 h, and HR = 2.74 (1.00–7.54) when the delay was 4 days.

Figure 1 represents the evolution of the risk of death after admission on a WE compared to admission on a WD, both in Internal Medicine patients and in the hospital as a whole, according to the time elapsed from admission until the patient was assessed by the physicians of his or her department.

Discussion

This study corroborates that patients admitted to hospital for urgent problems during WE suffer a higher risk of death than those admitted on WD. The study also shows that the factor with the greatest effect on this increased risk of death is the time that elapses from admission by the physicians on duty until the patient's care is taken over by the physicians of the department to which the patient was admitted; as a result, Friday is the day with the highest risk of death after admission and, in contrast, Sunday has no weekend effect.

Although this problem has been extensively studied, there is a lack of evidence on what happens to Internal Medicine patients, usually with multiple serious conditions. Among the few articles analysing Internal Medicine patients is that of Marco et al.4, a multicentre study conducted with a large sample size that found that mortality at 48 h of admission increased by up to 60% on weekends in all hospitals in the country. In our case, we also analysed other longer lengths of stay, and found that the WE effect was no longer significant after the fifth day of admission. The importance of the first days of admission has been widely described in patients with various diagnoses admitted to different hospital services3,4,23,38, and it has been described that the risk of death after admission decreases by 1% for each additional day of stay23. We have found that the main factor behind this effect is the time elapsed from emergency admission to the start of normal hospital care, corroborated by differentiating between weekend days and finding that patients admitted on Sunday do not suffer this effect as they receive normal care the following day. It is logical to think that doctors who admit a patient at 3 in the morning do not have such a clear mind and can make mistakes, however, in WD the admitted patient will be evaluated after a few hours by a doctor with a clear head who can fix diagnostic errors or omissions of treatment as a result of the fatigue of the doctor on duty; by contrast, when admitted on the WE these possible errors will take time to be detected since the inpatient will not be evaluated again until Monday. The same results were reproduced when we analysed the base that included all the patients in the hospital, with somewhat attenuated risks with respect to the Internal Medicine patients, perhaps because the heterogeneity of diagnoses was much greater in these patients; and the same occurred again after excluding patients admitted for childbirth and caesarean section, which we did because they are a very important group (17% of the total) with a specific profile of sex, young age, low mortality and short stay.

There are studies whose patients had an increased risk of death after admission over a WE and this effect was reduced by opening a medical admissions unit39, while other studies found a reduction of mortality after providing enhanced WE staffing for acute medical inpatient services40. It has been pointed out that the excess mortality patterns of the WE vary widely for different diagnostic groups, and recognising these patterns should help to minimise the excess mortality41. However the adoption of seven day clinical standards in the delivery of emergency hospital services did not reduce the WE effect42, and the authors of other investigations conclude that further work is required to examine non evaluated potential explanations for the WE such as staffing levels and other organisational factors7. Some important outputs suggest that the relationship between consultant presence and mortality is tenuous at best, and that causal pathways for the WE effect may extend into the prehospital setting, in the community that precede hospital admission43,44. Our study proposes to work on the time elapsed from emergency admission to the start of normal hospital care.

The importance for patient prognosis of prompt attention is evident, as is the availability of the hospital's full diagnostic and therapeutic capacity, which is not fully available during the WE periods. The problem we have studied is not diagnosis or treatment in the emergency services, whose analysis would require a different design. What we have studied is the hospital mortality of patients once admitted, that is, mortality related to the care received during their stay in the beds of the different specialties. This is compounded by another factor that suggests that the problem may worsen over the years: given the progress of medicine, the increasing prevalence of multiple simultaneous chronic diseases and demographic ageing, Internal Medicine services in Spain have gone from 460,000 discharges in 2005 to almost 750,000 in 201945.

The patients in our study were those admitted through the emergency department. In our environment (Canary Islands), palliative care only exists as hospital units and it has the same accessibility on WD and WE; unfortunately, patients end up dying in the hospital regardless of the day of the week. The results of the group of patients admitted to Internal Medicine, excluding those who were moved to the palliative care unit, were similar to the results in the hospital-wide patients.

Respiratory infections, heart failure and sepsis are the most frequent discharge diagnoses in Internal Medicine28,46. For this reason, these are the diseases that we have adjusted for in our analysis. It is noteworthy that the diagnosis of sepsis had a high mortality, with a threefold increase in the risk of death in the first days of stay in our centre. However, in 2020, the so-called "sepsis code" was introduced in our hospital, an alarm code for early assessment and follow-up in the ICU, so these figures may have improved with respect to the results prior to that year.

The main limitations of our study are related to the retrospective design and the use of an administrative database. We could not analyse many factors: interindividual differences among on-call doctors, proportion of misdiagnoses in the ER, mortality variability during periods of high care pressure, or differentiate whether the death of a patient admitted to IM occurred in an ER bed or in a department bed; in addition, in an administrative database there is always a risk of coding errors as severity and comorbidities were not registered for the purpose of the study. However, the quality of the MBDS is proven and many rigorous studies with its data have been validated, and our findings are consistent with the well-known ‘weekend-effect’ and the ‘dose–response relationship’ (the longer it takes before the regular teams sees the patient, the higher the chance of dying) is an extra proof of validity of our results. Another limitation of our study can be related to not analysing data relating to the medical personnel present every day in the hospital; although we describe in the Methods section the composition of the on-call medical team, it is not available the composition of the staff of each medical specialty along the studied period. One more limitation of the study is that it is a single-centre study and limited to 5 years, although the patient samples we studied for both Internal Medicine and the hospital-wide group are very large and give consistency to the data; on the other hand, as Tenerife is an island it represents a closed eco-system of care, which is useful in the context of resource utilisation on WD vs WE.

Conclusion

Whether it was IM patients or hospital-wide patients, hospital admission on WE increases mortality in patients with short stays, and the main factor associated with this is the time that elapses from admission until the patient's care is taken over by the department to which he/she was admitted. Therefore, there is a ‘dose–response relationship’ where Friday is the day with the highest risk of death after admission and, in contrast, Sunday has no weekend effect. Hospitals must implement measures that guarantee that patients admitted during the weekend are treated within a similar time frame as those admitted during weekdays.

Data availability

The data, the Bioethics Committee approval and the analysis plan that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Macfarlane, A. Variations in number of births and perinatal mortality by day of week in England and Wales. Br. Med. J. 2, 1670–1673. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.6153.1670 (1978).

Phillips, D. P. et al. Cardiac mortality is higher around Christmas and New Year’s than at any other time: The holidays as a risk factor for death. Circulation 110, 3781–3788. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000151424.02045.F7 (2004).

Barba, R. et al. Mortality among adult patients admitted to the hospital on weekends. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 17, 322–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2006.01.003 (2006).

Marco, J. et al. Analysis of the mortality of patients admitted to internal medicine wards over the weekend. Am. J. Med. Qual. 25, 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860610366031 (2010).

González-Gancedo, J. et al. Mortality and critical conditions in COVID-19 patients at private hospitals: weekend effect?. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. 25, 3377–3385. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202104_25750 (2021).

Quirós-González, V. et al. What about the weekend effect? Impact of the day of admission on in-hospital mortality, length of stay and cost of hospitalization. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 37, 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhqr.2022.04.002 (2022).

Honeyford, K. et al. The weekend effect: Does hospital mortality differ by day of the week? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18, 870. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3688-3 (2018).

Aldridge, C. et al. Weekend specialist intensity and admission mortality in acute hospital trusts in England: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 388, 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30442-1 (2016).

Zhou, Y. et al. Off-hour admission and mortality risk for 28 specific diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 251 cohorts. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5, e003102. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.003102 (2015).

Aylin, P. et al. Weekend mortality for emergency admissions. A large, multicentre study. Qual. Saf. Heal. Care 19, 213–17. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2008.028639 (2010).

Mohammed, M. A. et al. Weekend admission to hospital has a higher risk of death in the elective setting than in the emergency setting: A retrospective database study of national health service hospitals in England. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-87 (2012).

Freemantle, N. et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: An analysis of inpatient data. J. R. Soc. Med. 105, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2012.120009 (2012).

Walker, A. S. et al. Mortality risks associated with emergency admissions during weekends and public holidays: An analysis of electronic health records. Lancet 390, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30782-1 (2017).

Bell, C. M. & Redelmeier, D. A. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 663–668. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa003376 (2001).

Bendavid, E. et al. Complication rates on weekends and weekdays in US hospitals. Am. J. Med. 120, 422–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.067 (2007).

Ricciardi, R. et al. Do patient safety indicators explain increased weekend mortality?. J. Surg. Res. 200, 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.07.030 (2015).

Sharp, A. L., Choi, H. & Hayward, R. A. Don’t get sick on the weekend: An evaluation of the weekend effect on mortality for patients visiting US ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 31, 835–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.006 (2013).

Zambrana-García, J. L. & Rivas-Ruiz, F. Quality of hospital discharge reports in terms of current legislation and expert recommendations. Gac. Sanit. 27, 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.08.007 (2013).

Liu, S. F. et al. Mortality among acute myocardial infarction patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 13, 2320. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25415-8 (2023).

Kwok, C. S. et al. Weekend effect in acute coronary syndrome: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 8, 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872618762634 (2019).

Sorita, A. et al. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 25, 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2014.03.012 (2014).

Barnett, M. J., Kaboli, P. J. & Sirio, C. A. Rosenthal GE Day of the week of intensive care admission and patient outcomes: A multisite regional evaluation. Med. Care 40, 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200206000-00010 (2002).

Amigo, F., Dalmau-Bueno, A. & García-Altés, A. Do hospitals have a higher mortality rate on weekend admissions? An observational study to analyse weekend effect on urgent admissions to hospitals in Catalonia. BMJ Open 11, e047836. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047836 (2021).

Campbell, C., Woessner, H. & Freeman, W. D. Association between weekend hospital presentation and stroke fatality. Neurology 77, 700–701. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e9f07 (2011).

Ogbu, U. C. et al. A multifaceted look at time of admission and its impact on case-fatality among a cohort of ischaemic stroke patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.202176 (2009).

Haut, E. R. et al. Injured patients have lower mortality when treated by “full-time” trauma surgeons vs. surgeons who cover “part-time” trauma. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 61, 272–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000222939.51147.1c (2006).

Pronovost, P. J. et al. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically Ill patients a systematic review. JAMA 288, 2151–2162. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.17.2151 (2002).

Institute for the Improvement of Health Care Foundation (IMAS Foundation). RECALMIN Register. Patient care in the Internal Medicine units of the National Health System. (2021). https://www.fesemi.org/sites/default/files/documentos/publicaciones/recalmin-2021.pdf.

Pauls, L. et al. The weekend effect in hospitalized patients: A meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Med. 12, 760–766. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2815 (2017).

Becker, D. J. Do hospitals provide lower quality care on weekends?. Health Serv. Res. 42, 1589–1612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00663.x (2007).

Weeda, E. R. et al. Association between weekend admission and mortality for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: An observational study and meta-analysis. Intern. Emerg. Med 12, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1522-7 (2017).

Dobkin C. Hospital Staffing and Inpatient Mortality. 2003. https://people.ucsc.edu/~cdobkin/Papers/Old%20Files/Staffing_and_Mortality.pdf

Myers, R. P., Kaplan, G. G. & Shaheen, A. A. M. The effect of weekend versus weekday admission on outcomes of esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 23, 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/713789 (2009).

Clarke, M. S. et al. Exploratory study of the “weekend effect” for acute medical admissions to public hospitals in Queensland. Aust. Intern Med J 40, 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02067.x (2010).

Registro de altas de hospitalización: CMBD del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Portal estadístico del SNS. [Internet]. Accessed May 12, 2023, https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/SolicitudCMBD.htm.

Charlson, M. et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40, 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/001-9681(87)90171-8 (1987).

McCormick, P. J., Lin, H. M., Deiner, S. G. & Levin, M. A. Validation of the all patient refined diagnosis related group (APR-DRG) risk of mortality and severity of illness modifiers as a measure of perioperative risk. J. Med. Syst. 42, 81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-0936-3 (2018).

Ruiz, M., Bottle, A. & Aylin, P. P. The global comparators project: International comparison of 30-day in-hospital mortality by day of the week. BMJ Qual. Saf. 24, 492–04. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003467 (2015).

Brims, F. J. H. et al. Weekend admission and mortality from acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in winter. Clin. Med. J. R. Coll. Phys. Lond. 11, 334–339. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.11-4-334 (2011).

Leong, K. S. et al. A retrospective study of seven-day consultant working: Reductions in mortality and length of stay. J. R. Coll. Phys. Edinb. 45, 261–267. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2015.402 (2015).

Concha, O. P. et al. Do variations in hospital mortality patterns after weekend admission reflect reduced quality of care or different patient cohorts? A population-based study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 23, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002218 (2014).

Meacock, R. & Sutton, M. Elevated mortality among weekend hospital admissions is not associated with adoption of seven day clinical standards. Emerg. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2017-206740 (2017).

Bion, J. et al. Changes in weekend and weekday care quality of emergency medical admissions to 20 hospitals in England during implementation of the 7-day services national health policy. BMJ Qual. Saf. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011165 (2020).

Bion, J. et al. Increasing specialist intensity at weekends to improve outcomes for patients undergoing emergency hospital admission: The HiSLAC two-phase mixed-methods study. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr09130 (2021).

Institute for the Improvement of Health Care Foundation (IMAS Foundation). RECALMIN Register. Patient care in the Internal Medicine units of the National Health System. (2019). https://www.fesemi.org/sites/default/files/documentos/publicaciones/informe-recalmin2019.pdf

Canora, J. et al. Admittances characteristics by sepsis in the Spanish Internal Medicine services between 2005 and 2015: Mortality pattern. Postgrad. Med. 132, 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2020.1718388 (2020).

Acknowledgements

To the HUSNC for their willingness to provide data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C.P. and J.A.M.G. proposed the study and collected data. ACdL analysed the database. S.C.P. and A.C.d.L. a wrote the manuscript first draft. J.A.M.G. review the draft and translated the paper. All the author reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castaño-Pérez, S., Medina García, J.A. & Cabrera de León, A. The dose–response effect of time between emergency admission and inpatient care on mortality. Sci Rep 13, 22244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49090-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49090-5

- Springer Nature Limited