Abstract

Understanding population discrepancy in maternity continuum of care (CoC) completion, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa is significant for interventional plan to achieve optimal pregnancy outcome and child survival. This study thus investigated the magnitudes, distribution, and drivers of maternity CoC completion in Nigeria. A secondary analysis of 19,474 reproductive age (15–49 years) women with at least a birth (level 1) in 1400 communities (level 2) across 37 states covered in the 2018 cross-sectional survey. Stepwise regression initially identified important variables at 10% cutoff point. Multilevel analysis was performed to determine the likelihood and significance of individual and community factors. Intra-cluster correlation assessed the degree of clustering and deviance statistics identified the optimal model. Only 6.5% of the women completed the CoC. Completion rate is significantly different between communities “4.3% in urban and 2.2% in rural” (χ2 = 392.42, p < 0.001) and was higher in southern subnational than the north. Education (AOR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.20–2.16), wealth (AOR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.35–2.46), media exposure (AOR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.06–1.40), women deciding own health (AOR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.13–1.66), taking iron drug (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.43–2.35) and at least 2 dose of tetanus-toxoid vaccine during pregnancy (AOR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.02–1.78) are associated individual factors. Rural residency (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.43–2.35), region (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.43–2.35) and rural population proportion (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.43–2.35) are community predictors of the CoC completion. About 63.2% of the total variation in CoC completion was explained by the community predictors. Magnitude of maternity CoC completion is generally low and below the recommended level in Nigeria. Completion rate in urban is twice rural and more likely in the southern than northern subnational. Women residence and region are harmful and beneficial community drivers respectively. Strengthening women health autonomy, sensitization, and education programs particularly in the rural north are essential to curtail the community disparity and optimize maternity CoC practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal continuum of care (CoC) is an integrated model continuation of care initiated from pre-pregnancy till the period of postpartum with the dimension of time and place, towards strengthening maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH)1,2. Maternity CoC thus centered around antenatal care (ANC), intrapartum and postnatal care (PNC) services received by women during pregnancy, delivery of fetal and after childbirth respectively3. Completing the three essential maternity care are critical to; reduce pregnancy related morbidities and mortalities3,4.

Maternal morbidity and mortality hitherto remained a public health problem, particularly in the lower-middle-income countries (LMIC) with high-risk fertility behavior5,6,7. Approximately, 800 women dies from preventable pregnancy and childbirth related complications daily, whereas most of all maternal deaths occur in developing countries, with sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounting for two-third8,9. However, these maternal and neonatal morbidities and mortalities (especially in LMIC) could have been prevented if women adhere to the WHO recommendation on 4 optimum ANC contacts and the recently recommended 8 ANC contacts following the review10,11,12.

Worldwide, the top four countries “South-Sudan, Chad, Sierra-Leone and Nigeria” with highest maternal mortality ratio (MMR) “1150, 1140, 1140 and 917 per 100,000 livebirths” in 2019 are respectively in SSA13,14. Although, the most recent national survey in Nigeria reported a lower MMR of 512 (95% CI 447–578) per 100,000 livebirths, with neonatal (NMR), infant (IFR) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) of 39, 67 and 132 per 1000 livebirths in 2018 respectively, while Pregnancy related mortality ratio (PRMR) is 556 per 100,000 livebirths in the last decade15,16.

According to the Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), 67% (6% increase from 2013) of women aged 15–49 years received ANC and about 57% had at least four contacts in 2018, deliveries in a healthcare facility and deliveries assisted by SBA increased from 36 and 39% in 2013 to about 40% and 43% respectively in 2018, while PNC increased by 12% in the last decade (from 30% in 2008 to 42% in 2018) for women and is currently 38% for newborns15,16,17. However, the national aggregate obscures the regional and community level estimates. For instance, 17% of newborns in northwest received PNC compared to 72% in southwest. Also, 61% of women in urban received PNC compared to 30% in the rural.

Despite the recent increase, ANC, SBA and PNC coverage in Nigeria still fell short of the recommended 90% and thus slow progress in achieving reduced maternal and newborn mortality12,14,18,19. This is because many women in Nigeria and sub-Saharan African countries at large fail to either utilize any of these services or complete the vital maternity CoC but, rather drop out of the care continuum20,21,22. Meanwhile, maternity CoC completion has been identified as a core principle and framework to underpin strategies to save lives of newborns and mothers23. After all, independent increase in ANC, SBA and PNC has not resulted to a steep decrease in maternal and neonatal mortality, which will halt the sustainable development goal (SDG-3) targeted towards reducing MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 and NMR to 12 per 1000 livebirths by 203024. Hence the need for MNCH program that incorporated completion of maternity CoC model as evidently devised in Egypt in the 90’s to achieve reduced MMR and NMR25,26.

Studies has reported that education, wealth, place of residence, media access among other factors are associated with ANC utilization and underutilization in Nigeria27,28,29,30. Findings also emphasized on the fact that optimal ANC contacts predicts SBA use and the combination of both as well as maternal age, child size, level of education, household wealth and employment status are determinant of PNC use and non-use in Nigeria19,2131,32,33. There is dearth of literatures on factors associated with maternity CoC completion in Nigeria. However, maternal and husband’s educational level, locality, wealth and parity has been identified as determinant18, 22,34. Similar factors in addition to; women autonomy and accessible distance increase the chance of completing CoC in Ethiopia2,35,36. Whereas, listening to radio, birth order and signs of pregnancy complication are additional factors associated with maternity CoC completion in The Gambia37.

Although there is depth of studies on independent utilization of ANC, SBA and PNC in Nigeria12,14,19,21,27,29,31,32,33,38. Nevertheless, very few has combined the key maternity care to measure CoC coverage gaps and its determinants along the pathway of pregnancy to post-delivery period20,22. While Akinyemi et al. only assessed drop out, Oyedele et al. investigated CoC completion but without considering the disparities in community clusters20,22. Also, the subnational distribution of maternity CoC completion in Nigeria is unknown.

Thus, this study uniquely investigated the community differentials in magnitude of maternity gamut of care completion based on WHO recommendations, applied multilevel analysis to account for clustering effect and evaluate demographics and health-seeking predictors of maternity CoC completion. This study answered the following research questions; Any disparity in community prevalence of maternity CoC in Nigeria? What are the individual and community-level predictors of maternity CoC completion? What is the impact of subnational distribution on maternity CoC completion. The study outcome will provide evidence-based statistics/fact to assist in developing community-specific strategy to improve MNCH policy program.

Methodology

Study design, data and area

This is a secondary analysis of cross-sectional population-based survey from the nationally representative data of the 2018 Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS). The 2018 NDHS is a national representative survey that has been routinely collected in Nigeria since 1990 and often captured respondent across different locations in Nigeria. Administratively, Nigeria is divided into 6 geopolitical zones and each zone or region is subdivided into states and federal capital territory (FCT)16. As at 1990, Nigeria comprised of 21 states, 30 states in 1991 and up till now, comprises of 36 states and FCT since the creation of 6 more states in 1996 (Fig. 1)22.

Sampling technique and participants

The 2018 NDHS adopted a two-stage stratified sampling technique using the sampling frame of the Nigeria Population and Housing Census (NPHC) conducted in 2006 by the National Population Commission (NPC). The 36 states and FCT were subdivided into local government Areas (LGA) where urban and rural localities were selected at the first stage sampling (yielding 74 strata). The administrative units were further subdivided into Enumeration Areas (EA) that resulted to the selected 1400 clusters (580 in urban and 820 in rural) called the primary sampling unit (PSU) in the second stage. Thirty households were then selected per cluster (by equal-probability systematic sampling) to make a total of 42,000 households selected and postpartum women of age (15–49 years) were interviewed regarding ANC, SBA and PNC that makes up maternity continuum of care. Information on respondents’ demographic, economic and health indicators were also collected. Comprehensive information on the 2018 NDHS sampling methodology where 41,821 women participants (99% response rate) were recruited has been documented16.

Operational definition

Completion of maternity continuum of care is the outcome variable and, is simply an act of a woman finalizing the main maternal health services provided during pregnancy (Optimal ANC uptake), institutional delivery assisted by skilled births attendants (SBA use) and postnatal care immediately after childbirth till the sixth week of delivery (PNC visit)22,39.

Measure of outcome

CoC is define in this study as a dichotomous response to whether a post-partum woman received ANC in a healthcare facility at least 4 times during pregnancy, childbirths aided by SBA (doctor, nurses or midwifes) and PNC check for the mothers took place after childbirth. Thus, ANC, SBA and PNC are the three key component measures of the outcome variable.

The outcome was measured according to the WHO recommendations of at least 4 ANC visits and the use of SBA at birth10,11. The recently recommended 8 ANC contacts by WHO was not applied to avoid bias from setting stringent rule, since the DHS operationalization was based on birth in the last 5 years using the minimum of 4 ANC contacts, which is yet to even achieve required coverage and also the updated WHO guidelines for 8 ANC contacts were recently implemented after the births of most women respondents in the DHS in Nigeria16,40. The measure of PNC for mothers after birth was however due to the fact that most of maternal morbidity (e.g. Postpartum-hemorrhage, Puerperal-sepsis, etc.) and mortality occur in this period and therefore make it a crucial indicator in measuring maternity completion of care and even towards assessing the possible attainment of the SDG-38,41.

Explanatory variables

Explanatory variables in the study were classified based on individual demographic and autonomy, community, socio-economic, childbirth and mother interaction with healthcare system, similar to classification from previous studies and as a model framework for maternity continuum of care predictors2,4,35,36,37,41. The independent variable categories are also consistent with the variable classification on the DHS and previous literatures on maternity care service42,43,44,45,46. Also, the behavioral ecological framework was adopted to classify the independent factor as follows14,47.

Individual and household-level characteristics

Maternal age (15–24, 25–34, 35–49), level of education (none, primary, secondary, higher), marital status (unmarried, married), partner’s level of education (no education, primary, secondary, higher), religion (catholic/christian, islam, tradintional/other), ethnicity (hausa/fulani, igbo, yoruba, other), getting medical help; permission (not a big problem, big problem), women healthcare decision (partner alone, woman alone, joint decision). Wanted pregnancy (then, later no more), birth order (1, 2, 3, 4 +), provider of ANC (doctor, nurse/midwifery, auxiliary nurse/midwifery, CHEW/CHO, TBA, no one), tetanus toxoid vaccine taken (none, 1, 2+), institutional delivery (no, yes) delivery by CS (no, yes), child sex at birth (male, female), child size at birth (very large, larger than average, average, smaller than average, very small), Wealth status (poor, middle, rich), mass media exposure (no, yes), covered by health insurance (no, yes), medical help-money (not a big problem, big problem).

Community-level factors

Place of residence (urban, rural), region (northeast, northwest, northcentral, southeast south-south, southwest), medical help-distance (not a big problem, big problem) Community unemployment (low, average, high), community socio-economic (low, average, high), community rural proportion (low, high).

Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive analysis was performed and reported in frequency (percentage) for all categorical responses. The frequency and proportion reported was based on women characteristics by the CoC completion status (Yes or No) and thus the supporting bivariate Chi-square statistics was reported. The Pearson Chi-square was reported throughout as none of the expected cell count was < 5. Also, the Phi and Crammer’s V statistics that assessed the relationship between the women CoC completion and the binary/multinomial independent factors were reported respectively.

Further bivariate associations were evaluated using the forward stepwise regression approach such that the empty model (without independent factor) was first fitted, and the individual and community factors are then added in turn. Thus, the factors that significantly increase the − 2LogL at p < 0.10 were retained and added to the model and otherwise excluded. This validated the associated factors in the bivariate chi-square analysis as the factors measuring both child-sex and community illiteracy insignificantly add to the − 2logL. Also, identified the variables for inclusion in the multivariable analysis. Hence, the regression coefficients and Wald statistics were reported.

The multilevel (mixed-effect) binary logistic regression assessed the fixed individual-level effect and the random community-level effect. The respective adjusted effect (AOR) was reported for each individual and community factor. Estimate of the intra-class correlation (ICC) was determined from the null model and compared to the fitted full model to obtain the proportion of explained variation in the model which is referred to as the proportional change in variance (PCV). The median odds ratio (MOR) was assessed to evaluate the cluster-level risk of completing the CoC. The likelihood deviance, Akaike and Bayesian statistics compared the null, random, fixed, and full multilevel model fitness. Data management and analysis were conducted using Stata version 17.0 and all statistical tests and analysis were carried out at a 5% level of significance (95% confidence interval). Maps reported in this study were generated from Microsoft 360 (@Microsoft OpenStreetMap). Sampling weights indices included in the NDHS data (Women’s individual weight) were applied and the svyset command was used to adjust for disproportionate sample due to the complexity of the survey design. Multicollinearity was investigated through variance inflation factor (VIF) and controlled by excluding and substituting type of union (VIF > 5.0) with marital status (with weaker correlation coefficients) in the multivariable analysis.

The multilevel analysis

Multilevel model was fitted at each model stage (model-I, model-II model-III and model-IV) to evaluate enumeration area cluster dependencies in prediction of maternity continuum of care. Model-I is the empty model i.e., intercept only terms, model-II is the individual only term, model-III comprises of the community term while model-IV combined all the terms as a full model48,49. The individuals (postpartum women) within households are nested in communities’ enumeration area cluster. Therefore, resulted in a two-level mixed-effect logistic regression with fixed effect at the respondent’s household level and random effect at the community level. The two-level mixed effect model can be expressed as (Level 1, Level 2):

In general, the full multilevel model is produced when Eq. (2) is substituted into (1). Therefore, lead to Eq. (3) below.

where \(\ln \left( {\frac{{P_{ij} }}{{1 - P_{ij} }}} \right)\) is the odds of postpartum women completing the maternity continuum of care, \({\alpha }_{00}\) is the fixed intercept (grand mean), \({\tau }_{0j}\) is the community j random intercept term, \({\beta }_{(p)}\) are the regression coefficients of the independent variables or covariates, \({X}_{ij}\) are the set of individual i and community j predictors, \({e}_{ij}\) is the noise or error term, \({e}_{ij}\) and \({\tau }_{0j}\) are normally, identically and independently distributed with mean 0 and constant variance \({\sigma }^{2}\).

Thus, the ICC measured the degree of clustering based on heterogeneity between clusters i.e., the proportion of total variation in maternity CoC attributable to the community level random-effect component which can be expressed as:

where \({\sigma }_{u}^{2}\) is the between cluster variance (community random-component) and \(\left( {\frac{{\pi^{2} }}{3} = 3.291} \right)\) is the within community cluster variance from assumed normally distributed population49,50.

The explained variance is computed from the proportional change in variance (PCV) which estimates the difference in variance between the null and the model with at least a factor term (i.e., including covariates) as a ratio of the null model variance.

where \({\sigma }_{0}\) is the variance of the null model, \({\sigma }_{i}\) is the variance of observed factor for i is the number of factor or covariates terms in the models i.e., model II, III and IV21,49,50.

The median odds ratio (MOR) measures the odds of CoC completion at high-risk cluster relative to the low-risk cluster if two reproductive age women are randomly selected from the two clusters.

The fit statistics was assessed based on the likelihood deviance (− 2LL). Akaike (AIC) and Bayes (BIC) Information Criterion were computed from the respective model log likelihood. The model with the least deviance was however adjudged to best predict the CoC completion49,50,51.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was a secondary analysis and thus relies on the ethical clearance of the DHS which was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Inner City Fund (ICF) International Macro at Fairfax, Virginia, United States, and the country IRB (National Health Research Ethics Committee) in Nigeria. The author was granted access to the DHS data. Written informed consent was obtained from all survey participants prior to data collection. This study adheres to appropriate reporting guidelines and did not involve any conduct of experiment or clinical trial.

Results

Women characteristics and association with maternity CoC completion

Table 1 presented the women sample distribution and the bivariate association with maternity CoC completion. Most (48.4%) women are 25–34 years, married (97.1%) and without formal education (46.8%). About 45% (8752) are poor (only 0.8% completed CoC) while 35.1% (with 30.8% incomplete CoC) are rich. Over 51% have had four births (only 2.5% completed CoC) while only 15.5% had one birth. Only 39.5% are exposed to mass media (Table 1). Only 5.1% and 6.1% of women that receive TT (52.5%) and iron drug (69.4%) completed the CoC. About 97% (6% CoC completion rate) had vaginal birth, health insurance only covered 2.3% of the women and only 39.8% had health facility delivery with distance being a problem in 28.3% (5519) (Table 1). About 61.5% reside in rural areas with high rural proportion and poverty rate of 75.3% and 42.9% respectively. All the women factors were associated with CoC completion (ANC4 + SBA + PNC) at p < 0.10 except child sex (p-value = 0.821) and community illiteracy (p-value = 0.931) (Table 1).

Coverage of maternity continuum of care completion

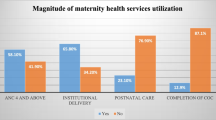

The coverage of maternity CoC completion is shown in Fig. 2. Overall, 6.5% (1269) of the women completed the maternity CoC while as high as 93.5% (59.3% in rural and 34.2% in urban) did not complete the maternity gamut of care (Fig. 2).

Community prevalence of maternity continuum of care

Figure 3 shows prevalence of maternity CoC by urban and rural communities. Prevalence of optimal ANC is different by 1.4% between urban and rural (Fig. 3). Less than half (13.6%) of the women who had optimal ANC in the rural (28.0%) continue to SBA (Fig. 3). The proportion of continuation to PNC reduces by about 6 folds from 23.4 to 4.3% in urban and from 13.6% to 2.2% in rural. CoC completion rate in urban (4.3%) is almost twice the rural (2.2%) (Fig. 3).

Stepwise forward regression analysis of CoC completion predictors

The stepwise logit model predictors of CoC completion are shown in Table 2. Woman’s age (p-value = 0.434), ethnicity (p-value = 0.617), pregnancy desire (p-value = 0.312), birth order (p-value = 0.437), health insurance (p-value = 0.265), medical permission (p-value = 0.512), child sex (p-value = 0.846) and child size(p-value = 0.860) and community illiteracy (p-value = 0.955) were not associated with maternity CoC completion at p < 0.10 and were therefore removed in the model (Table 2). Overall, 18 identified women factors that significantly increase in the log likelihood (Wald statistics ≥ 3) when added in turn at p < 0.10 were retained in the model (Table 2).

Multilevel predictors of maternity CoC completion among women (15–49 years)

The predictors of maternity CoC completion are shown in Table 3 (model I–IV). Model I is the null model with the constant term only. All the predictors group in the individual level model II are significant except for subgroup that receive 1 TT in pregnancy (p > 0.05), traditional religion (p > 0.05) and auxiliary ANC provider (p > 0.05) (Table 3). The community predictors in model III are only insignificant for the predictor group of the community poverty (p > 0.05). The full model IV that combined model I-III shows that odds of CoC completion increase with education and wealth (Table 3). Odds of CoC completion is 35% higher among married than unmarried and among women that received 2 doses of TT than those that receive 0 (AOR = 1.35; 95% CI 1.02–1.80). media exposure increases the likelihood by 22% (AOR = 1.22; 95 % CI 1.06–1.40). Women who received ANC from CHEW/CHW (AOR = 0.15; 95% CI 0.09–0.25) and TBA (AOR = 0.05; 95% CI 0.02–0.10) are less likely than those that received from doctors to complete the CoC respectively (Table 3). Women who took Iron drug (AOR = 1.84; 95% CI 1.43–2.35) and have CS delivery(AOR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.37–2.11) are almost twice as likely to complete the CoC. Place of residence, geopolitical zone and community rural proportion are significant (p < 0.05) community predictors (Table 3). The community level cluster variances and the ICC is large for the null model I and decreases as the factors are added in model II-IV. Thus, 28.5% of the CoC completion effect is attributable to the community predictors with 63.2% of the variation explained in the full CoC model compared to the null model. The median odds ratio shows that CoC completion is twice as likely in high-risk community compared to the low-risk community (Table 3).

Assessment of the maternity CoC model adequacy

The fit statistics of the maternity CoC model is presented in Table 3. The deviance statistics (− 2LL) computed for each of the specified model I–IV are 8480.38, 7478.96, 8128.04 and 7416.90 respectively. The full model-IV (mixed-effect) has the least deviance (7416.90) (Table 3). Similarly, the values of the Akaike and Bayes information criteria (AIC = 7488.89; BIC = 7772.14) for the full model-IV is the least of all the models and therefore perform best (Table 3).

Subnational distribution of maternity continuum of care completion

Figure 4 shows the distribution of maternity continuum of care completion by states. Completion rate is higher in Southern region “Enugu (29.9%), Oyo (24.5%), Imo (24.0%), Ekiti (22.8%)” than in Northern region “Kebbi (0.4%), Zamfara (0.7%)” among others states where there are more dropouts (Fig. 4). Also, very high proportion of Women dropout from the CoC completion in Sokoto (98.9%), Yobe (98.8%), Taraba (98.4%), Katsina (98.3%), Jigawa (98.1%) (Fig. 4).

Subnational analysis of maternity continuum of care completion

Table 4 present the state proportion and effect on maternity CoC completion relative to the largest (1620, 8.32%) women population in Kano state. Of the 6.52% (1269/19,474) maternity CoC completion prevalence in Nigeria, CoC completion was highest in Oyo (0.80%) followed by Kaduna (0.54%), Rivers (0.45%), Imo (0.43%), Lagos (0.42%) and Enugu (0.42%), while 0% maternity CoC completion was seen in Bayelsa (Table 4). CoC completion was near 0% in Kebbi (0.02%), Sokoto (0.03%) and Zamfara (0.03%) (Table 4). Compared to Women in Kano, Enugu women are about 13.5 times more likely to complete the maternity CoC (OR = 13.48, 9.32–19.49) (Table 4). Women in Ekiti (OR = 10.84, 7.21–16.28), Imo (OR = 10.64, 7.37–15.37) and Oyo ((OR = 10.47, 7.46–14.67) are more than 10 times more likely to Complete the maternity CoC than those in Kano (Table 4). Whereas the odds of completing maternity CoC reduces by 80%, 69% and 67% in Kebbi (OR = 0.20, 0.06–0.57), Zamfara (OR = 0.31, 0.13–0.83) and Sokoto (OR = 0.33, 0.13–0.70) respectively (Table 4). Odds of maternity CoC completion was also high by more than 5 folds in Ondo, Rivers and Kwara states when compared to Kano (Table 4).

Discussion

This study applied the multilevel analysis techniques to investigates the individual and community prevalence and predictors as well as the subnational distribution of the maternity CoC completion ‘from pregnancy to childbirth and post-delivery i.e., ANC, SBA and PNC’ based on the WHO recommendations for optimal health and survival of mother and newborn. This is to achieve an evidence-based policy strategy specific to supporting and improving MNCH programming at the community and subnational level and, towards achieving the 2030 SDG-3 goal.

It was observed that more than two-third of the pregnant women in Nigeria attended ANC, but less than three-fifths (57.4%) completed the minimum recommended four visits. This is similar to national survey report and studies on ANC compliance with WHO recommendation in Nigeria12,16. Prevalence of SBA continuation after optimal ANC uptake is 37% and completion rate of the three essential maternity CoC (i.e., ANC SBA and PNC) is only 6.5%. However, nearly two-third of the prevalence of maternity CoC completion in Nigeria was observed in the urban compared to the one-third in the rural. Which can be ascribed to the easier access to maternal healthcare in urban compared to rural and hence the higher likelihood of maternity CoC completion in urban than the rural as reported in the recent multi-country study in SSA52.

Overall, prevalence of continuation of care diminishes as women progress from pregnancy to delivery and post-delivery with significant dropout observed at the PNC stage. This is because those that utilized SBA tends to be absent from PNC as they are less likely to have post-delivery complications compared to those that do not utilize SBA at delivery and thus, high dropout rate was observed at PNC as found in study investigating dropout pattern in Nigeria and other SSA countries20,22,53. Also, completion rate is cumulatively higher in southern states than northern states owing to contribution of Oyo with highest prevalence of maternity CoC completion.

Education, residence, wealth, decider of healthcare, tetanus toxoid taken in pregnancy, place of residence, distance to medical facility, geopolitical zone, among other individual and community-level factors were significantly related to maternity continuum of care. Child sex and community illiteracy level were however not associated with women completion of CoC. Comparable factors were reported in studies in SSA to be associated with maternity CoC completion2,4,22,37,52,54.

It was discovered that odds of gamut of maternity care uptake, continuation and completion increase with progression in education and wealth. Maternal education effect is understandably due to exposure and ability to listen, read and write as women with higher education are more likely to be able to comprehend and follow medical instructions and prescriptions than those with secondary education39, and those with secondary education perform better in maternal service utilization than those with primary education only and so on. Agreeing with recent findings from studies on the effect of female education and moderating role of partner education on maternal healthcare in SSA55,56. The effect of wealth is attributed to being able to bear expenses of maternity range of cares as commitment can be motivated by financial strength and it is not surprising that women who had the big problem of getting money for medical help are less likely to complete the maternity gamut of care. This is in congruent with study outcome on positive effect of wealth and health insurance coverage on maternal healthcare in SSA57,58.

Women exposure to media and healthcare decision making positively influence maternity CoC completion by 22% and 37% respectively. This explains the role of media (listening to radio, watching television, and reading newspapers) as well as the women autonomous health decision making on their own health compared to partner decision as only pregnant women knows her health better. Similar findings were reported from studies on factors associated with maternity healthcare service utilization and CoC completion in African settings18,34,36,37,39,52,54.

Furthermore, the chance of completing maternity CoC is higher in women who had a minimum of two required number of tetanus injection than those that had none. Since the WHO recommended 2 or more TT immunization required for women to develop antibodies to protect their newborn against tetanus and will encourage more ANC visits to facilitate optimal reception of ANC and subsequently drives SBA and PNC as previously enunciated to have a big impact on infant59. Also, Iron drug taken in pregnancy almost twice increase the likelihood of a woman completing the CoC compared to those that do not take iron supplement in pregnancy. This was corroborated by the findings from previous study on maternity predictors of CoC coverage22.

However, having nurses, TBA and CHEW/CHW as ANC provider, big problem of getting money for medical help and health facility delivery are the individual-level predictors with negative influence on the maternity CoC completion. Hence women whose ANC was provided by CHEW and TBA are about 7 and 20 times less likely to complete the maternity CoC respectively. Having hospital birth almost twice reduces the likelihood of CoC completion as those who had hospital births after ANC are more likely to have vaginal birth and dropout of PNC. This is in consonance with findings on dropouts of CoC, predictors of maternity CoC in Nigeria and the determinants of maternity CoC in Cambodia20,22,46,60. Also, Caesarian section delivery positively drive CoC completion after ANC utilization as a result of the necessity to seek for medical help after delivery as women who had CS birth are more likely to attend PNC for follow-up care on surgical site due to poor postnatal quality of life which adversely impacted the optimality of newborn breastfeeding compared to women who had vaginal birth61,62.

It was observed that place of residence, geopolitical zone and community rural percentage are the Community-level factors associated with maternity CoC completion in Nigeria. Thus, women who resides in the rural and within community of high rural population proportion have 23% and 28% excess risk of not completing the maternity CoC. Which can be ascribed to the prevailing problem of limited access to health facility majorly worsened by distance, health finances and socio-cultural factors in the rural communities as substantiated by recent studies in SSA22,46,52. Nevertheless, women in the southern (south–south, southeast, and southwest) region are (30%, 59% and 91%) more likely to complete the maternity CoC than their counterpart in the north.

The significance of Community-level variance indicated the suitability of the multilevel analysis to evaluate dependency in maternity CoC completion. The ICC implies that 28.5% of the variation in maternity CoC completion are attributable to the community heterogeneity. Thus, 63.2% of the variation in maternity CoC completion were explained by the community-level effect relative to the null model. Corresponding findings were observed in studies applying multilevel method to evaluate predictors of maternity CoC dropout and completion20,48,63. The model assessment based on deviance statistics further stressed the robustness of the multilevel method and identified the full model with random and fixed effect (mixed effect) component as the optimal model across the four specified model “Model I–IV”. Studies on multilevel analysis also reported findings analogous to comparison among null, random, fixed and the mixed effect models50,51.

When the subnational impact on maternity CoC completion was compared with the state with largest women population (Kano), Women in Enugu state reported highest effect and are about 13 times more likely to complete the maternity CoC. Also, Ekiti, Imo and Oyo women are more than 10 times as likely to achieve maternity CoC completion. The chance of maternity CoC completion is about 7 times more in Ondo and Rivers than Kano. Also, the subnational effect was positive in Kwara, FCT, Osun, Abia, Lagos, Edo, Akwa-Ibom, Kaduna, Bauchi, Delta, Ogun, Benue, and Anambra. However, the effect was negative in Kebbi, Zamfara, Sokoto, Yobe and Katsina as pregnant women in these states are 2–5 times less likely to complete the maternity range of cares.

Strengths and limitations

The study was not free from recall bias majorly associated with cross-sectional studies as it relies on respondent’s events in the last 5 years preceding the survey. Inference from the study should be interpreted based on association not causal factor as it does not control for temporality and other condition to ascertain causality. Analysis was also subjected to the operationalized variables measured in the DHS based on the survey questionnaire as information such as type of healthcare facility (primary, secondary, and tertiary) were not collected. However, the use of nationally representative large dataset improves the target population generalizability. Also, the application of sampling weight further enhanced the accuracy and reliability of the study findings therein. The multilevel analysis technique that accounted for clustering effect by assessing variations between clusters was suitable for the cluster survey design and can also be regarded as strength.

Conclusions

In conclusion, only one in fifteen pregnant women completed the maternity continuum of care. Completion rate is however significantly different between communities, with the two-thirds of the prevalence in urban and only one-third in the rural. Women CoC completion is twice more likely in the urban clusters than the rural and thus highlight place of residence, community rural proportion and geopolitical zone as the community drivers of the maternity gamut of care completion. Chance of CoC completion increase by education and wealth but decrease by cadre of ANC provider. Women autonomy to her own healthcare decision, media exposure, tetanus toxoid and iron drug taken in pregnancy positively influence CoC completion while health facility delivery and medical finances negatively influence CoC completion. About One-third of the variation in maternity CoC completion is attributable to the significant community-level factors. Hence the mixed-effect model was optimal. Women CoC Completion rate is higher in southern than northern sub-nationals, with Enugu, Ekiti, Imo and Oyo the four topmost states with highest likelihood of maternity CoC completion.

Recommendations

The generally low coverage of maternity CoC completion is an indication for the need to strengthen maternity healthcare practice through sensitization programs, capacity buildings and increase access to quality maternal healthcare service particularly in the rural. ANC packages should be reviewed to encourage optimal visits and discourage dropouts. Northern sub-nationals should emulate what works and learn from what doesn’t work in the Southern region. Contextual research on dropout of maternity CoC completion is required particularly in the rural to understand the militating socio-cultural factors towards devising interventional programming strategy.

Data availability

The de-identified data is available in the public domain . Analyzed dataset used in this current study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author and can be access at the open repository of the DHS program www.dhsprogram.com.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CoC:

-

Continuum of care

- ICC:

-

Intra-cluster correlation

- IMR:

-

Infant mortality rate

- LMIC:

-

Lower–middle-income country

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality ratio

- MNCH:

-

Maternal newborn and child health

- NDHS:

-

Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey

- NMR:

-

Neonatal mortality rate

- PNC:

-

Postnatal care

- PRMR:

-

Pregnancy related mortality ratio

- SBA:

-

Skilled birth attendants

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SSA:

-

Sub Saharan Africa

- U5MR:

-

Under 5 mortality rate

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- PCV:

-

Proportional change in variance

- CS:

-

Caesarian section

- CHEW:

-

Community health extension worker

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- TBA:

-

Traditional birth attendants

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

References

De Graft-Johnson, J., Kerber, K., Tinker, A., Otchere, S., Narayanan, I. & Shoo, R. The continuum of care – reaching mothers and babies at the crucial time and place. Oppor. Africa’s Newborns 23–36 (2006).

Asratie, M. H., Muche, A. A. & Geremew, A. B. Completion of maternity continuum of care among women in the post-partum period: Magnitude and associated factors in the northwest, Ethiopia. . PloS One 15(8), e0237980. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237980 (2020).

Banke-Thomas, O. E., Banke-Thomas, A. O. & Ameh, C. A. Factors influencing utilisation of maternal health services by adolescent mothers in Low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1246-3 (2017).

Haile, D. et al. Level of completion along continuum of care for maternal and newborn health services and factors associated with it among women in Arba Minch Zuria woreda, Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia: A community based crosssectional study. PLoS One 15(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221670 (2020).

USAID. Ending preventable maternal mortality: USAID maternal health vision for action. USAID Matern. Health Vis. Action 1–56 (2015).

Bauserman, M. et al. Maternal mortality in six low and lower-middle income countries from 2010 to 2018: Risk factors and trends. Reprod. Health 17(Suppl 3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00990-z (2020).

Salawu, M. M. et al. Preventable multiple high-risk birth behaviour and infant survival in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03792-8 (2021).

Maternal Mortality Fact sheet, Maternal Health. Who 1–5 [Online]. Available: /entity/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/index.html. (2015).

Merdad, L. & Ali, M. M. Timing of maternal death: Levels, trends, and ecological correlates using sibling data from 34 sub-Saharan African countries. PloS one 13(1), e0189416. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189416 (2018).

World Health Organization. WHO Antenatal Care Randomized Trial: Manual for the Implementation of the New Model (2002).

WHO, WHO Recommendation on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. (2016).

Fagbamigbe, A. F., Olaseinde, O. & Setlhare, V. Sub-national analysis and determinants of numbers of antenatal care contacts in Nigeria: Assessing the compliance with the WHO recommended standard guidelines. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03837-y (2021).

WHO. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA (World Bank Group and United Nations Population Division, 2019).

Fagbamigbe, A. F. & Oyedele, O. K. Multivariate decomposition of trends, inequalities and predictors of skilled birth attendants utilisation in Nigeria (1990–2018): A cross-sectional analysis of change drivers. BMJ Open 12(4), e051791. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051791 (2022).

National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demograhic Health Survey, 2013. (Abuja, 2014).

National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. in Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. (Abuja, Nigeria, And Rockville, 2019).

National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] & ICF International. in Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, 2008. (DHS Measure Macro, New York and Nigeria Population Commission, 2009).

Dahiru, T. & Oche, O. M. Determinants of antenatal care, institutional delivery and postnatal care services utilization in Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 21, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.21.321.6527 (2015).

Fagbamigbe, A. F., Hurricane-Ike, E. O., Yusuf, O. B. & Idemudia, E. S. Trends and drivers of skilled birth attendant use in Nigeria (1990–2013): Policy implications for child and maternal health. Int. J. Womens. Health 9, 843–853. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S137848 (2017).

Akinyemi, J. O., Afolabi, R. F. & Awolude, O. A. Patterns and determinants of dropout from maternity care continuum in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1083-9 (2016).

Chukwuma, A., Wosu, A. C., Mbachu, C. & Weze, K. Quality of antenatal care predicts retention in skilled birth attendance: A multilevel analysis of 28 African countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1337-1 (2017).

Oyedele, O. K., Fagbamigbe, A. F., Akinyemi, O. J. & Adebowale, A. S. Coverage-level and predictors of maternity continuum of care in Nigeria: Implications for maternal, newborn and child health programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05372-4 (2023).

Kerber, K. J., de Graft-Johnson, J. E., Qar Bhutta, Z. A., Okong, P., Starrs, A. & Lawn, J. E. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: From slogan to service delivery. [Online]. Available: www.thelancet.com. (2007).

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). (2015).

Graham, W. J. & Hussein, J. Universal reporting of maternal mortality: An achievable goal?. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 94(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.04.004 (2006).

Hamed, A., Mohamed, E. & Sabry, M. Egyptian status of continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: Sohag Governorate as an example. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 7(6), 1. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijmsph.2018.0102607032018 (2018).

Adewuyi, E. O. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Nigeria: A comparative study of rural and urban residences based on the 2013 Nigeria demographic and health survey. PLoS One 13(5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197324 (2018).

El-Khatib, Z., Odusina, E. K., Ghose, B. & Yaya, S. Patterns and predictors of insufficient antenatal care utilization in Nigeria over a decade: A pooled data analysis using demographic and health surveys. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(21), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218261 (2020).

Oluwamotemi, C. A., Edoni, E. E. & Ukoha, C. E. Factors associated with utilization of antenatal care services among women of child bearing in Osogbo, Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Rep. Gynaecol. 3(1), 32–42 (2020).

Fagbamigbe, A. F., Olaseinde, O. & Setlhare, V. Sub-national analysis and determinants of numbers of antenatal care contacts in Nigeria: Assessing the compliance with the WHO recommended standard guidelines. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03837-y (2021).

Agho, K. E. et al. Population attributable risk estimates for factors associated with non-use of postnatal care services among women in Nigeria. BMJ Open 6(7), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010493 (2016).

Igboanusi, C. J. C., Sabitu, K., Gobir, A. A., Nmadu, A. G. & Joshua, I. A. Factors affecting the utilization of postnatal care services in primary health care facilities in urban and rural settlements in Kaduna State, north-western Nigeria. Am. J. Public Health Res. 7(3), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajphr-7-3-4 (2019).

Olajubu, A. O., Olowokere, A. E., Ogundipe, M. J. & Olajubu, T. O. Predictors of postnatal care services utilization among Women in Nigeria: A facility-based study. J. Nurs. Scholarship 51(4), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12473 (2019).

Ayo Stephen, A. & Odunayo Joshua, A. Adebowale & Akinyemi Maternal health assessment. Afr. J. Reprod. Health (2016).

Shitie, A., Assefa, N., Dhressa, M. & Dilnessa, T. Completion and factors associated with maternity continuum of care among mothers who gave birth in the last 1 year in Enemay District, Northwest Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7019676 (2020).

Tizazu, M. A. et al. Completing the continuum of maternity care and associated factors in debre Berhan town, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 14, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S293323 (2021).

Oh, J., Moon, J., Choi, J. W. & Kim, K. Factors associated with the continuum of care for maternal, newborn and child health in the Gambia: A cross-sectional study using Demographic and Health Survey 2013. BMJ Open 10(11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036516 (2020).

Fagbamigbe, A. F. & Idemudia, E. S. Barriers to antenatal care use in Nigeria: Evidences from non-users and implications for maternal health programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0527-y (2015).

Tsega, D. et al. Maternity continuum care completion and its associated factors in Northwest Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1309881 (2022).

N. Federal Ministry of Health, Antenatal Care: An Orientation Package for Healthcare Providers. (2017).

Wang, W. & Hong, R. Levels and determinants of continuum of care for maternal and newborn health in Cambodia-evidence from a population-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0497-0 (2015).

Gabrysch, S. & Campbell, O. M. R. Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-34 (2009).

Kyei, N. N. A., Campbell, O. M. R. & Gabrysch, S. The influence of distance and level of service provision on antenatal care use in Rural Zambia. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046475 (2012).

Adedokun, S. T. & Uthman, O. A. Women who have not utilized health Service for Delivery in Nigeria: Who are they and where do they live?. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2242-6 (2019).

Ameyaw, E. K. & Dickson, K. S. Skilled birth attendance in Sierra Leone, Niger, and Mali: Analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8258-z (2020).

Oyedele, O. K. Disparities and barriers of health facility delivery following optimal and suboptimal pregnancy care in Nigeria: Evidence of home births from cross-sectional surveys. BMC Women’s Health 23(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02364-6 (2023).

Ryvicker, M. A conceptual framework for examining healthcare access and navigation: A behavioral-ecological perspective. Soc. Theory Health 16(3), 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0053-2 (2018).

Chaka, E. E. Multilevel analysis of continuation of maternal healthcare services utilization and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2(5), e0000517. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000517 (2022).

Abebe, G. F., Belachew, D. Z., Girma, D., Aydiko, A. & Negesse, Y. Multilevel analysis of the predictors of completion of the continuum of maternity care in Ethiopia; Using the recent 2019 Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05016-z (2022).

Fagbamigbe, A. F., Morhason-Bello, I. O., Kareem, Y. O. & Idemudia, E. S. Hierarchical modelling of factors associated with the practice and perpetuation of female genital mutilation in the next generation of women in Africa. Plos One 16(4), e0250411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250411 (2021).

Tesema, G. A., Seretew, W. S., Worku, M. G. & Angaw, D. A. Trends of infant mortality and its determinants in Ethiopia: Mixed-effect binary logistic regression and multivariate decomposition analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03835-0 (2021).

Alem, A. Z., Shitu, K. & Alamneh, T. S. Coverage and factors associated with completion of continuum of care for maternal health in sub-Saharan Africa: A multicountry analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04757-1 (2022).

Muluneh, A. G., Kassa, G. M., Alemayehu, G. A. & Merid, M. W. High dropout rate from maternity continuum of care after antenatal care booking and its associated factors among reproductive age women in Ethiopia, Evidence from Demographic and Health Survey 2016. PLoS One 15(6), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234741 (2020).

Shitie, A., Assefa, N., Dhressa, M. & Dilnessa, T. Completion and factors associated with maternity continuum of care among mothers who gave birth in the last 1 year in Enemay District, Northwest Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy 20, 20. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7019676 (2020).

Amwonya, D., Kigosa, N. & Kizza, J. Female education and maternal health care utilization: Evidence from Uganda. Reprod. Health 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01432-8 (2022).

Apanga, P. A., Kumbeni, M. T., Sakeah, J. K., Olagoke, A. A. & Ajumobi, O. The moderating role of partners’ education on early antenatal care in northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04709-9 (2022).

Sanogo, N. A. & Yaya, S. Wealth status, health insurance, and maternal health care utilization in Africa: Evidence from Gabon. Biomed. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4036830 (2020).

Comfort, A. B., Peterson, L. A. & Hatt, L. E. Effect of health insurance on the use and provision of maternal health services and maternal and neonatal health outcomes: A systematic review. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 31(4 SUPPL), 2 (2013).

Perrett, K. P. & Nolan, T. M. Immunization during pregnancy: Impact on the Infant. Pediatr. Drugs 19(4), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-017-0231-7 (2017).

Chham, S., Radovich, E., Buffel, V., Ir, P. & Wouters, E. Determinants of the continuum of maternal health care in Cambodia: An analysis of the Cambodia demographic health survey 2014. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21(1), 410. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03890-7 (2021).

Torkan, B., Parsay, S., Lamyian, M., Kazemnejad, A. & Montazeri, A. Postnatal quality of life in women after normal vaginal delivery and caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-4 (2009).

Oyedele, O. K. Effect of caesarian section delivery on breastfeeding initiation in Nigeria: Logit-based decomposition and subnational analysis of cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 13(10), e072849. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072849 (2023).

Emiru, A. A., Alene, G. D. & Debelew, G. T. Women’s retention on the continuum of maternal care pathway in west Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: Multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02953-5 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the ICF Macro, owners of the DHS data for granting access to the dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K.O. Conceptualized and designed the study, wrote the methodology and performed and interpreted the formal analysis. O.K.O. wrote, edited, and reviewed the original article. The author read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oyedele, O.K. Multilevel and subnational analysis of the predictors of maternity continuum of care completion in Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 13, 20863 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48240-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48240-z

- Springer Nature Limited