Abstract

In semi-arid environments, resources necessary for survival may be unevenly distributed across the landscape. Gould’s wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) are spatially restricted to mountainous semi-arid areas of southwestern United States and Mexico, and information on their distribution and habitat use is limited. We described how landcover type and topographical features influenced space use and habitat selection by Gould’s wild turkeys in southeastern Arizona. We used GPS data from 51 Gould’s wild turkeys to describe resource selection during 2016–2017 in southeastern Arizona, USA. We estimated home ranges and calculated resource selection functions using distance from landcover types, slope, aspect, and elevation at used locations and random locations within individual home ranges. Gould’s wild turkeys selected areas closer to pine forest and water. Likewise, Gould’s wild turkeys selected locations with moderate elevations of 1641 ± 235 m (range = 1223–2971 m), and on north and west facing slopes with a 10° ± 8.5 (range = 0.0–67.4°) incline. Our findings suggest that conserving portions of the landscape with appropriate topography and landcover types as described above will promote habitat availability for Gould’s wild turkeys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wildlife species preferentially select habitats that best meet their ecological needs1,2,3. In semi-arid environments, resources necessary for survival may be limited and unevenly distributed across the landscape. Vegetative communities in semi-arid environments are dynamic, fluctuating in quality due to variation in temperature, precipitation, and exploitation4,5,6,7. Thus, identifying critical habitats for various wildlife species across arid landscapes is important to prioritize management activities and direct conservation efforts.

The Gould’s wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo Mexicana) originally occurred from central Mexico into southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico8,9. Native Gould’s wild turkey were predominantly extirpated from most of the southwestern United States by the 1920s because of habitat degradation and unregulated hunting8. Starting in 1983 and continuing through 2018, the Arizona Game and Fish Department led translocation efforts to restore Gould’s wild turkeys throughout southeastern Arizona using birds from Mexico and populations from earlier translocation efforts9,10,11. Additional restoration efforts were conducted in 2014–2017, when Gould’s wild turkeys from Arizona were used to supplement populations in New Mexico (J. Heffelfinger, Arizona Game and Fish Department, personal communication).

Limited suitable habitat is thought to suppress Gould’s wild turkey population growth in the mountains of southeastern Arizona due to limited dispersal opportunities12,13. Previous research indicated that female Gould’s wild turkeys preferred pinyon pines (Pinus spp.), pinyon-ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoids) and riparian habitats14. Riparian habitats may provide important roosting and foraging habitats14,15,16,17,18, but riparian habitats can be limited in mountainous, semi-arid areas that often experience drought and wildfire14,19.

Given the climatic extremes of the southwestern United States, topographical features can influence vegetative growth and suitability for various wildlife species20,21. Elevation gradients create climatic variation over relatively short distances22,23, whereas slope and aspect influence vegetative structure and species composition24,25,26,27,28,29. Within the range of Gould’s wild turkeys, moderate elevations (1,364–2,982 m) and north-facing slopes (10–65°) often support important oak (Quercus spp.), pine (Pinus spp.), juniper (Juniperus spp.), and manzanita (Arctostaphylos pungens) that provide roosting and foraging areas14,15,30,31,32. Conversely, xeric vegetation, at certain elevations, can dominate south-facing slopes which are hot and dry, and may be avoided by Gould’s wild turkeys18,24,33.

Our objectives were to describe how landcover type and topographical features influenced space use and habitat selection by Gould’s wild turkeys in southeastern Arizona. We hypothesized that Gould’s wild turkeys would select to be closer to specific landcover types, and that topographical features would influence selection. Specifically, we predicted that Gould’s wild turkeys would select areas closer to pine forest and water at moderate elevations on north facing slopes, as these areas presumably provide increased roosting18 and foraging14,32 opportunities compared to higher elevations and south facing slopes.

Study area

We conducted our research in the Coronado National Forest in southeastern Arizona, which encompasses the sky islands extension of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Our specific study areas included the Pinaleño, Chiricahua, Huachuca, and Patagonia mountains located Graham, Cochise, and Santa Cruz counties (Fig. 1). All study sites consisted of semidesert grasslands of low to moderate shrub cover comprised of catclaw acacia (Acacia greggii), grama (Bouteloua spp.), needlegrass (Achnatherum spp.), Parry’s agave (Agave parryi), soaptree yucca (Yucca elata), and wheatgrass (Elymus spp.) found at elevations between 1,100 to 1,700 m. Madrean evergreen woodland including alligator juniper (J. deppeana), Arizona white oak (Q. arizonica), and Emory oak (Q. emoryi) were found at 1,200–2,300 m elevation. Petran montane conifer forest containing Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), New Mexico locust (Robinia neomexicana), and Ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa) occurred at 2,000–3,050 m elevation, whereas Petran subalpine conifer consisting of Douglas fir and Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) occurred at 2,450–3,800 m in elevation34. The highest of Arizona’s sky island mountain ranges was the Pinaleño Mountains, with a peak elevation of 3,267 m and base elevation of 974 m, compared to the Chiricauhas with a peak elevation of 2,974 m with a base elevation of 1,345 m. Similarly, the Huachuca Mountains had a peak elevation of 2,885 m with a base elevation of 1,524 m. The lowest sky island mountain range was Patagonia Mountains with a peak elevation of 2,200 m and a base elevation of 1,219 m18. Riparian corridors occurred along steep slopes and ravines, comprised of Arizona sycamore (Platanus wrightii) and Fremont cottonwood (Populus fremontii). Average annual temperatures ranged from 7.2° C to 16.7° C, respectively35 and average precipitation was approximately 579 mm18.

Methods

Capture and handling

We captured Gould’s wild turkeys with walk-in traps baited with cracked corn and peanuts during winter (January-March) 2016 and 201711,34,36. Likewise, between 9–15 May 2017, Gould’s wild turkeys were captured on private property near Patagonia, Arizona in conjunction with an in-state translocation project35. We aged Gould’s wild turkeys based on presence of barring on the 9th and 10th primaries and sex of individuals was established based on the coloration of the breast feathers37. All individuals were equipped with a backpack-style global positioning system-very high frequency (GPS-VHF) transmitter38 (Biotrack, Wareham, Dorset, United Kingdom). We programmed transmitters to record hourly locations between 0500 and 2000, and 1 roosting location (23:58:58) until the battery died or the unit was recovered39. We immediately released non-translocated Gould’s wild turkeys at the capture location following processing. Translocated Gould’s wild turkeys were moved approximately 64 km to an area of similar topography and vegetation within our study area. Cohen35 indicated that after release, Gould's wild turkeys selected pine-juniper woodlands and riparian corridors immediately, and that there were no changes in roosting behavior. We remotely downloaded GPS data either via a fixed-wing aircraft with an ultra high frequency (UHF) handheld receiver (Biotrack) or ground based radio-tracking. All methods including turkey capture, handling, and marking procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations approved by the Louisiana State University Agricultural Animal Care and Use Committee.

Environmental covariates

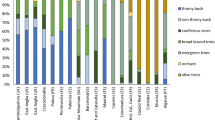

We examined selection of landscape features in relation to a set of environmental covariates relevant to the ecology of Gould’s wild turkey. We quantified topographical features (slope, aspect, elevation) using digital elevation models from the United States Geological Survey National Elevation Dataset (http://lta.cr.us.gs.gov/NED, accessed 10 Oct 2021)34. We converted aspect from a continuous variable to a categorical variable by binning degrees < 45 and ≥ 315 as north, ≥ 45 and < 135 as east, ≥ 135 and < 225 as south, and ≥ 225 and < 315 as west. We obtained year-specific, 30 m resolution spatial data on landcover from the Cropland Data Layer (Cropscape) provided by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (National Agricultural Statistics Service 2015). We recoded and combined landcover in R (v. 4.1.0; R Core Team, 2022) using package CropScapeR40 to create 6 unique landcover types (water, pine forest, hardwood forest, mixed pine-hardwood forest, barren, and shrub). We calculated the nearest distance from each turkey use and available points to each landcover type, using the Euclidean distance tool in ArcMap 10.8 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). We used landcover distance metrics for subsequent analysis instead of a classification or categorical approach41.

Resource selection

We calculated 99% home ranges by fitting dynamic Brownian bridge movement models (dBBMMs) to the time-specific location data39 using package move42 in Program R (R Core Team 2022). We used an error estimate of 20 m, a moving window size of 7 locations, and a margin setting of 3 locations39,43.

We used resource selection functions (RSFs) to examine relationships between 3 topographical features (elevation, slope, aspect) and distance metrics from 6 landcover types (barren, hardwood forest, mixed pine hardwood forest, pine forest, shrub, water) to Gould’s wild turkeys use within individual home ranges (3rd-order selection) following a design III approach suggested by Manly44. We compared used points within individual home ranges to available points systematically sampled (every 3rd pixel, i.e., 90 m) within each home range45. We tested for collinearity between each of our covariates and excluded covariates using Pearson’s correlation with a r > 0.6046. We fit a single global (i.e., including all covariates) generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) to include a random intercept for each individual turkey, with a binomial response distribution (logistic regression) and logit link to the used-available data for Gould’s wild turkeys44,47. We included a random intercept for each individual turkey to account for individual variation in response to available conditions and unbalanced sampling48. We used the lme4 package in program R49 with a binary (0 = available, 1 = used) response variable to model resource selection. We rescaled all variables by subtracting their mean and dividing by their standard deviation prior to modeling50. We did not use model selection techniques to rank candidate models because the relative effect of all covariates were of interest. To assess how well our RSF model explained the data, we used area under the receiver-operating characteristic curves (AUC) calculated with the pROC package in program R51. An AUC value of 0.5 indicated the model provided estimates no better than random predictions, but values greater than 0.7 indicated a better model fit with more accurate predictions.

Ethical approval

Turkey capture, handling, and marking procedures were approved by the Louisiana State University Agricultural Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol number A2015-07).

Results

We captured 45 Gould’s wild turkeys (2016: 19 females, 1 male; 2017: 25 females) during January-March 2016 and 2017, and captured and translocated 17 individuals (6 females, 11 males) in May 2017. We censored 11 individuals (2016: 6 females; 2017: 1 translocated females, 3 translocated males, and 1 non-translocated female) due to transmitter failure or post-release mortality. We created 51 individual Gould’s wild turkeys home ranges (2016: 13 females and 1 male; 2017: 29 females and 8 males) from 156,184 GPS locations. Transmitters collected data for an average of 7 months (SD ± 2, range 1–15), but because of varying deployment dates we had GPS locations spanning all 12 months (Table S1). The average 99% home range size was 2,001 ha (SE ± 239; range 143–7,518).

In our global model, parameter estimates for landscape characteristics and landcover types were statistically different from zero except for east aspect (Table 1). We kept all variables in the global model as none were correlated with other variables. Selection probability was positively associated with north and west facing aspects, and Gould’s wild turkeys avoided south facing aspects (Table 1, Fig. 2). Gould’s wild turkeys avoided hardwood forest, shrub, and barren habitat (Table 1, Fig. 3), but selected for water, pine forest, and mixed hardwood pine forest (Fig. 3). As elevation and slope increased, probability of selection decreased (Fig. 3). Gould’s wild turkeys selected for an average elevation of 1,641 ± 235 m (range = 1,223–2,971 m; Fig. 4), with a mean slope of 10 ± 8.5° (range = 0.0–67.4°; Fig. 4). The AUC estimate was 0.74, indicating suitable accuracy of our model.

Discussion

Our findings support the hypothesis that landcover type and topographical features influence resource selection of Gould’s wild turkeys. We noted a positive relationship between Gould’s wild turkeys use and north facing slopes, but a negative relationship with south facing slopes, which was consistent with the roost site selection analysis by18. In addition, we found evidence consistent with previous studies documenting the importance of pine forests and avoidance of shrub habitat and bare ground32. Conversely, our findings suggest that Gould’s wild turkeys preferred lower elevations than those reported in previous studies11,14,32. The average home range size for our individuals was smaller than home range sizes reported in other studies, although our home range estimates may be biased slightly high as some of the translocated birds may still be conducting searching activities35. We offer that the resultant differences we found were likely due to the use of finer scale spatial data obtained from GPS transmitters compared to earlier studies that relied on VHF transmitters and triangulation38.

Resource availability across a landscape can influence how species select habitats20,52, and Gould’s wild turkeys occur in arid environments where resources are often less abundant53,54. Our results indicated that Gould’s wild turkeys selected for locations at moderate elevations (1,223–2,971 m). Elevations of 1,000–2,300 m were associated with oak and pine-oak forest, juniper, and riparian corridors across our study areas. Juniper and mature pine-oak forests with open canopies provide open-herbaceous understories, which create food sources for Gould’s wild turkeys14. Likewise, large mature pines provide turkeys with suitable roost sites18, demonstrating the importance of pine forests near suitable areas for foraging.

In the southwestern United States, north-facing slopes are cooler relative to south-facing slopes because they receive less sunlight and offer more shade and moisture, which influences the distribution and growth patterns of vegetation55,56. Hence, north-facing slopes support more productive vegetative communities, that are important to Gould’s wild turkeys14. Conversely, south-facing slopes are drier and warmer24,33, and are typically dominated by barren and shrub landcover types that turkeys use less15,32,57. Furthermore, Gould’s wild turkeys may seek shade and cooler areas associated with north facing slopes to maintain appropriate body temperatures58,59. We suggest future research examine how thermal conditions may influence resource selection by Gould’s wild turkeys60,61.

Our findings provide additional support for the conservation and restoration of forest communities on north and west facing slopes across the southern sky islands of southern Arizona, in particular mixed hardwood pine forests that provide important resources for Gould’s wild turkey. Likewise, our findings provide substantive evidence that pine and mixed hardwood pine forests at lower to moderate elevations (1223–2971 m) are important to sustainability of Gould’s wild turkeys. Management activities should prioritize retention of pine forests near riparian corridors because they provide important roosting and foraging habitat in semi-arid landscapes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Johnson, D. H. The comparison of usage and availability measurements for evaluating resource preference. Ecology 61, 65–71 (1980).

Hutto, R. L. Habitat selection nonbreeding, migratory land birds. In Habitat selection in birds (ed. Cody, M. L.) 455–467 (Academic Press, 1985).

Block, W. M. & Brennan, L. A. The habitat concept in ornithology: Theory and applications. In Current Ornithology (ed. Power, D. M.) 35–91 (Springer, 1993).

Copeland, S. M., Bradford, J. B., Duniway, M. C. & Schuster, R. M. Potential impacts of overlapping land-use and climate in a sensitive dryland: A case study of the Colorado Plateau, USA. Ecosphere 8, 1–25 (2017).

Holmgren, M. et al. Extreme climatic events shape arid and semiarid ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 4, 87–95 (2006).

Huan, J. et al. Global semi-arid climate change over last 60 years. Clim. Dyn. 46, 1131–1150 (2016).

Tietjen, B. et al. Climate change-induced vegetation shifts lead to more ecological droughts despite projected rainfall increases in many global temperate drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2743–2754 (2016).

Schemnitz, S. D. & Zeedyk, W. D. Gould’s turkey. In The Wild Turkey: Biology and Management (ed. Dickson, J. G.) 350–360 (Stackpole Books, 1992).

Lerich, S. P. & Wakeling, B. F. Restoration and survival of Gould’s wild Turkeys in Arizona. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 10, 277–281 (2011).

Maddrey, R. C. & Wakeling, B. F. Crossing the border the Arizona Gould’s restoration experience. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 9, 83–87 (2005).

Wakeling, B. F. & Heffelfinger, J. R. Habitat suitability model predicts habitat use by translocated Gould’s wild turkeys in Arizona. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 10, 283–290 (2011).

Wakeling, B. F. Survival of Gould’s turkey transplanted into the Galiuro mountains, Arizona. USDA Forest Service Wildlife Proceedings RMRS-P-5: 227–234 (1998).

Lerich, S. P. & Cardinal, C. J. Historical and potential growth of Gould’s wild turkey populations in New Mexico. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 46, e1277 (2022).

York, D. L. & Schemnitz, S. D. Home range, habitat use, and diet of Gould’s turkeys, Peloncillo Mountains, New Mexico. Southwest. Natl. 48, 231–240 (2003).

Potter, T. D., Schemnitz, S. D. & Zeedyk, W. D. Status and ecology of Gould’s turkey in New Mexico. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 5, 1–24 (1985).

Figert, D. E. Status, Reproduction, and Habitat Use of Gould’s Turkey in the Peloncillo Mountains of New Mexico (New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, USA, 1989).

Schemnitz, S. D., & Zornes, M. L. Management practices to benefit Gould’s turkey in the Peloncillo Mountains, New Mexico. Pages 461–464 in Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean Archipelago: the Sky Islands of southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. L. F. DeBano, P. F. Folliott, A. Ortega-Rubio, G. J. Gottfried, R. H. Hamre, C. B. Edminster, technical coordinators, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service General Technical Report RM-GTR-264, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA (1995).

Bakner, N. W., Fyffe, N., Oleson, B., Smallwood, A., Heffelfinger, J. R., Chamberlain, M. J., & Collier, B. A. Roosting ecology of Gould’s wild turkeys in southeastern Arizona. J. Wildl. Manag. e22277 (2022).

Oetgen, J. et al. Evaluating Rio Grande wild turkey movements post catastrophic wildfire using two selection analysis approaches. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 11, 127–141 (2015).

Chapin, F. S., Matson, P. A., Mooney, H. A. & Vitousek, P. M. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology (Springer-Verlag, 2002).

Ragan, K., Schipper, J., Bateman, H. L. & Hall, S. J. Mammal use of washes in semi-arid Sonora, Mexico. J. Wildl. Manag. 86, e22322 (2022).

Dahlgren, R. A., Boettinger, J. L. & Huntington, G. L. Soil development along an elevational transect. Geoderma 78, 207–236 (1997).

Lomolino, M. V. Elevation gradients of species density: Historical and prospective views. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 10, 3–13 (2001).

Cantlon, J. E. Vegetation and microclimates on north and south slopes of Cushetunk Mountain, New Jersey. Ecol. Monogr. 23, 241–270 (1953).

Holland, P. G. & Steyn, D. G. Vegetational responses to latitudinal variations in slope angle and aspect. J. Biogeogr. 2, 179–183 (1975).

Armesto, J. J. & Martínez, J. A. Relations between vegetation structure and slope aspect in the Mediterranean region of Chile. J. Ecol. 66, 881–889 (1978).

Badano, E. I., Cavieres, L. A., Molina-Montenegro, M. A. & Quiroz, C. L. Slope aspect influences plant association patterns in the Mediterranean matorral of central Chile. J. Arid Enviorn. 62, 93–108 (2005).

Poulos, H. M. & Camp, A. E. Topographic influences on vegetation mosaics and tree diversity in the Chihuahuan Desert Borderlands. Ecology 91, 1140–1151 (2010).

Zapata-Rios, X., Brooks, P. D., Troch, P. A., McIntosh, J. & Guo, Q. Influence of terrain aspect on water partitioning, vegetation structure and vegetation greening in high-elevation catchments in northern New Mexico. Ecohydrology 9, 782–795 (2016).

Lafon, A. & Schemnitz, S. D. Distribution, habitat use, and limiting factors of Gould’s turkey in Chihuahua, Mexico. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 7, 185–191 (1995).

Lafon-Terrazas, A. Distribution, habitat use and ecology of Gould's turkey in Chihuahua, Mexico. Dissertation, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, USA (1997).

Wakeling, B. F., Boe, S. R., Koloszar, M. M. & Rogers, T. D. Gould’s turkey survival and habitat selection modeling in southeastern Arizona. Natl. Wild Turkey Symp. 8, 101–108 (2001).

Pook, E. & Moore, C. The influence of aspect on the composition and structure of dry sclerophyll forest on Black Mountain, Canberra. Austr. J. Bot. 14, 223–242 (1966).

Collier, B. A., Fyffe, N., Smallwood, A., Oleson, B. & Bakner, N. Reproductive ecology of Gould’s wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) in Arizona. Wilson J. Ornithol. 131, 667–679 (2019).

Cohen, B. S. et al. Movement, spatial ecology, and habitat selection of translocated Gould’s wild turkeys. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 46, e1270 (2022).

Fyffe, N., Smallwood, A., Oleson, B., Chamberlain, M. J. & Collier, B. A. Nesting perserverance by a female Gould’s wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) under multiple direct predation threats. Wilson J. Ornithol. 130, 1041–1047 (2018).

Pelham, P. H. & Dickson, J. G. Physical characteristics. In The Wild Turkey: Biology and Management (ed. Dickson, J. G.) 32–45 (Stackpole Books, 1992).

Guthrie, J. D. et al. Evaluation of a global positioning system backpack transmitter for wild turkey research. J. Wildl. Manag. 75, 539–547 (2011).

Cohen, B. S., Prebyl, T. J., Collier, B. A. & Chamberlain, M. J. Home range estimator method and GPS sampling schedule affect habitat selection inferences for wild turkeys. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 42, 150–159 (2018).

Chen, B. CropScapeR: Access Cropland Data Layer Data via the 'CropScape' Web Service (2020). (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=CropScapeR).

Conner, L. M., Smith, M. D. & Burger, L. W. A comparison of distance-based and classification-base analyses of habitat use. Ecology 84, 526–531 (2003).

Kranstauber, B., Kays, R., LaPoint, S. D., Wikelski, M. & Safi, K. A dynamic Brownian bridge movement model to estimate utilization distributions for heterogeneous animal movement: The dynamic Brownian bridge movement model. J. Anim. Ecol. 81, 738–746 (2012).

Byrne, M. E., McCoy, J. C., Hinton, J., Chamberlain, M. J. & Collier, B. A. Using dynamic Brownian bridge movement modeling to measure temporal patterns of habitat selection. J. Anim. Ecol. 83, 1234–1243 (2014).

Manly, B. F. J., McDonald, L. L., Thomas, D. L., McDonald, T. L. & Erickson, W. P. Resource Selection by Animals: Statistical Design and Analysis for Field Studies 2nd edn. (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002).

Benson, J. F. Improving rigour and efficiency of use-availability habitat selection analyses with systematic estimation of availability. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 244–251 (2013).

Dormann, C. F. et al. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 36, 027–046 (2013).

Johnson, C. J., Nielsen, S. E., Merrill, E. H., McDonald, T. L. & Boyce, M. S. Resource selection functions based on use-availability data: Theoretical motivation and evaluation methods. J. Wildl. Manag. 70, 347–357 (2006).

Muff, S., Signer, J. & Fieberg, J. Accounting for individual-specific variation in habitat selection studies: Efficient estimation of mixed-effects models using Bayesian or frequentist computation. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 80–96 (2020).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2014).

Gelman, A. Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Stat. Med. 27, 2865–2873 (2008).

Zipkin, E. F., Grant, E. H. C. & Fagan, W. F. Evaluating the predictive abilities of community occupancy models using AUC while accounting for imperfect detection. Ecol. Appl. 22, 1962–1972 (2012).

Whittaker, R. H. Gradient analysis of vegetation. Biol. Rev. 42, 207–264 (1967).

Hall, G. I. et al. Rio Grande wild turkey habitat selection in the southern great plains. J. Wildl. Manag. 71, 2583–2591 (2007).

Collier, B. A., Guthrie, J. D., Hardin, J. B. & Skow, K. L. Movements and habitat selection of male Rio Grande wild turkeys during drought in south Texas. J. Southeast. Assoc. Fish Wildl. Agencies 4, 94–99 (2017).

Titshall, L. W., O’Connor, T. G. & Morris, C. D. Effect of long-term exclusion of fire and herbivory on the soils and vegetation of sour grassland. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 17, 70–80 (2000).

Morrison, M. L., Marcot, B. & Mannan, W. Wildlife-Habitat Relationships: Concepts and Applications 3rd edn. (Island Press, 2012).

Márquez-Olivas, M. E., García-Moya, C.-R. & Islas, and H. Vaquera-Huerta.,. Roost sites characteristics of wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo mexicana) in Sierra Fria, Aguascalientes, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 78, 163–173 (2007).

Wolf, B. O. Global warming and avian occupancy of hot deserts: A physiological and behavioral perspective. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 73, 395–400 (2000).

Moses, M. R., Frey, K. J. & Roemer, G. W. Elevated surface temperature depresses survival of Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rats: Will climate change cook a desert icon?. Oecologia 168, 257–286 (2011).

Carroll, J. M., Davis, C. A., Elmore, R. D., Fuhlendorf, S. D. & Thacker, E. T. Thermal patterns constrain diurnal behavior of a ground-dwelling bird. Ecosphere 6, 1–15 (2015).

Nelson, S. D. et al. Fine-scale resource selection and behavioral tradeoffs of eastern wild turkey broods. J. Wildl. Manag. 86, e22222 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all the volunteers from the Arizona State Chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation, Arizona Game and Fish Department, University of Arizona Wildlife and Fisheries Society, and others for assistance capturing, monitoring, and collecting field data. Special thanks to A. Munig for help in securing funding. This material was based upon work that was partially supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U. S. Department of Agriculture, McIntire Stennis project under No. 7001494.

Funding

Our research was funded and supported by the Louisiana State University Agricultural Center, the Arizona State Chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, and the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Georgia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.U.: writing-original draft (lead); conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting). P.W.: formal analysis (lead); data curation (supporting); writing-review and editing (supporting). N.B.: formal analysis (supporting); data curation (supporting); writing-review and editing. B.B.: conceptualization (supporting); writing-review and editing (supporting). N.F.: data curation (supporting); writing-review and editing. B.O.: data curation (supporting); project administration (supporting). A.S.: data curation (supporting); project administration (supporting). J.H.: funding acquisition (equal); project administration (supporting); writing-review and editing (supporting) B.C.: conceptualization (equal); writing-review and editing (supporting); funding acquisition (equal); project administration (lead). M.C.: conceptualization (supporting); writing-review and editing (supporting). All authors consent for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ulrey, E.E., Wightman, P.H., Bakner, N.W. et al. Habitat selection of Gould’s wild turkeys in southeastern Arizona. Sci Rep 13, 18639 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45684-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45684-1

- Springer Nature Limited