Abstract

Social media (SM) exerts important effects on health-related behaviors such as eating behaviors (EB). The present study was designed to determine the direct and indirect association of SM addiction with EB in adolescents and young adults through body image (BI). In this cross-sectional study, 12–22 years old adolescents and young adults, with no history of mental disorders or psychiatric medications usage were studied through an online questionnaire shared via SM platforms. Data were gathered about SM addiction, BI, and EB in its sub-scales. A single approach and multi-group path analyses were performed to find possible direct and indirect associations of SM addiction with EB through BI concerns. Overall, 970 subjects, 55.8% boys, were included in the analysis. Both multi-group (β = 0.484, SE = 0.025, P < 0.001) and fully-adjusted (β = 0.460, SE = 0.026, P < 0.001) path analyses showed higher SM addiction is related to disordered BI. Furthermore, the multi-group analysis showed one unit increment in SM addiction score was associated with 0.170 units higher scores for emotional eating (SE = 0.032, P < 0.001), 0.237 for external stimuli (SE = 0.032, P < 0.001), and 0.122 for restrained eating (SE = 0.031, P < 0.001). The present study revealed that SM addiction is associated with EB both directly and also indirectly through deteriorating BI in adolescents and young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, communication through the internet has become an integral part of daily life1. In 2019, it has been reported that almost 72% of the world's population used online social networks, and this number is increasing every year2. In Iran, it was reported that in 2018, more than 47 million Iranians used online social networks3. Among internet-based social media users, adolescents are a large group that spends a prolonged time on these media. It has been reported that more than 88% of 13–18 years old adolescents in the United States have access to the internet. In 2018, 45% of American teenagers reported being almost constantly online, while this rate was 24% in 20154. In Iran, it has been reported that in 2021, adolescents use smart devices for an average of 7.5 h a day5. Social media overuse was shown to be associated with several physical6 and mental health issues7. This excessive social media engagement can reach the point where it can be considered a form of addiction8,9.

The Internet and social media encourage users to create profiles with assigned profile pictures and it has been suggested that people's attractiveness in online profiles affects their popularity10. Hence, the online environment is full of images of peers and celebrities that create opportunities for social comparisons. Negative comparisons may occur when social media users compare their online images with others11. Body dissatisfaction which arises from these comparisons is known to be a major risk factor for body image concern and decreased self-esteem12,13,14. Pieces of evidences support the sociocultural theory which suggests social agents including the media, peers, and parents as determinants of internalized body shape ideals, and the most of time, these ideals are unrealistic ideals of body shape, thus leading to body image dissatisfaction15,16. Body image dissatisfaction can cause eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder17 and lowering physical activity18. Therefore social media engagement or addiction might affect eating behaviors by increasing body image concerns.

Moreover, social media addiction was seen to affect behaviors toward health19,20 and eating21. Social media users are often exposed to dietary and health advices, which may have no scientific basis. Frequent sharing of food-related posts and advertisements on social media platforms may also lead to changes in eating behavior and an increase in the desire to eat unhealthy foods1.

In the case of adolescents, since a large part of the social and emotional development of this generation occurs on the internet and mobile phones, the impact of online social networks on them is much greater22. Most adolescents are at risk when using social media due to their limited ability for self-management and vulnerability to peer pressure22. While both genders are at risk, girls were shown to be more susceptible to social media risks23.

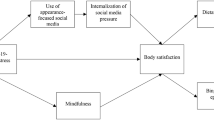

Increasing the use of social media, especially among adolescents, has shown the need for various researches. Although several research projects were conducted on social media use and its effects on health-related behaviors in both western and non-western countries4,6,20,24,25,26,27, there are still information gaps in this area. Considering the important linkage between social media and health-related behaviors including eating habits both directly and indirectly through deteriorated body image, the present study was designed to determine the direct and indirect association of social media addiction with eating behavior in adolescents and young adults. We hypothesized that social media addiction can affect eating behaviors through body image deterioration. Figure 1 depicts a schematic pathways of direct, indirect, and total associations of multi-group path analysis between social media addiction, body image, and eating behavior.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted from September 5, 2021, to October 2, 2021. The study was conducted among Iranian adolescents and young adults drawn from all regions in Iran. An online questionnaire was designed on the basis of the Porsline website (www.porsline.ir) to collect data. The link to the online questionnaire was sent through social media platforms (WhatsApp and Instagram) and the recipients were free to respond if they wished.

The survey questionnaire included a front-page describing the objectives, the target population, the details of the questions, and a statement that implied filling out the questionnaire is quite optional, and your voluntarily answering and finally submitting the questionnaire is considered as your consent to participate in the study. For teenagers, although they were allowed to have access to social media from their parents, there was also a statement to consult with their parents or legal guardians for participation. For this purpose, after the initial explanations on the front page, in the first question, we asked participants to state their consent (or in the case of teenagers for their legal guardian consent) by ticking the informed consent question as a requirement to enter the questionnaire. Thus, web-based informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation. After initiating the answering to the questionnaire, participants were free to leave the survey at any stage before final submission, and the incomplete questionnaires were not saved. The protocol of the study was following the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.SUMS.SCHEANUT.REC.1400.049). To prevent repeated responses, the domain restricted access using repeated IP addresses.

Study population

Adolescents and young adults aged 12–22 years were eligible to participate in the study if they had access to devices that could connect to the internet and were literally skilled to be able to answer the questions on the form. Individuals with any history of diagnosed mental disorders or consuming any psychiatric medications were excluded from the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were mentioned on the front page of the online survey and were confirmed by the answers given to the related questions: “Have you ever had a history of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, etc.?” and “If you have a history of mental disorders, have you ever received any medications?”.

Since the main goal of the present study was to conduct structural equation modeling and considering the fact that for this modeling, sample size estimation is not determined using closed-form formulas, rules of thumb were used for sample size determination. It is proposed to recruit 50–500 participants for this method28. To increase the study power and to ensure proper power for the multi-group analysis, we considered a larger sample size.

Data gathering

The online survey comprised three main sections including the front page, the questionnaire, and the final closing page. After the front page with general information about the study, the online platform of the questionnaire showed each question on a single page. The questionnaire consisted of 4 main sections.

First, the demographic characteristics of participants such as age, gender (boy or girl), educational status (school student, college student, graduated, or leave), the highest educational level (high school, BS, MS, or general physician), following any diet (no special diet, weight gain, weight reduction, special medical diets, or sports diet), having network job (any online activity which demands spending time in social media to earn money), being the administrator of any social media pages (with the educational, entertainment, financial purposes, or not at all), and physical activity level (PAL) (sedentary, casual, moderate, or intense exercise)29 were recorded. The anthropometric records were self-reported for height and weight. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the reported data with the standard formula ([weight (kg)]/[height (m)]2). Socioeconomic status (SES) was recorded using the possession of 9 specific items by the household. Based on the number of items possessed by the household, participants were categorized into 3 groups deprived (possessed 3 items or less), semi-affluent (for possession of 4 to 6 items), and affluent (household possessed more than 6 items)30.

Three questions were used to identify ineligible participants. The first question was asked about age, thus records out of the predefined age range (12–22 years) were excluded. The second and third questions asked about any diagnosed mental disorders or consuming psychiatric medications. In case of positive answers to any of these questions, the respondent was removed from the final analysis.

In the second part, the dependence of individuals on social media was assessed using the Social Media Addiction Scale Student Form (SMAS-SF)31. This questionnaire was designed for students aged 12–22 years and its validity and reliability have been previously published31. This questionnaire consisted of 29 questions and 4 sub-dimensions with 5-point Likert-type responses including “1 = strongly disagree”, “2 = disagree”, “3 = neither agree nor disagree”, “4 = agree”, and “5 = strongly agree”. Sub-dimensions assessed respondents’ virtual tolerance, virtual communication, virtual problem, and virtual information. The scores ranged from 29 to 145. Higher scores indicate that the person considers him/herself more "social media addicted"31.

To validate the Persian version of the SMAS-SF based on the method of Lawshe32, first, the questionnaire was translated into Persian, and then back translation was done to confirm the concepts in Persian. The content validity was assessed by an expert panel composed of 10 specialists. The content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity index (CVI) were evaluated. To test the reliability, a test–retest was done. The questionnaire was completed by 40 participants in the age range of 12–25 years old twice with a 3 weeks intervals.

In the third part, the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) was used to evaluate respondents’ eating behavior33. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire were previously confirmed by Kargar et al.34. The questionnaire contained 33 questions in 3 sub-domains. The first sub-domain includes questions related to emotional eating (EB-EE) indicating overeating in response to emotions, which includes 13 questions. The second sub-domain consists of 10 questions and measures eating in response to external stimuli (EB-ES) (food-related stimuli, regardless of states of hunger and satiety). The third sub-domain contains 10 questions and evaluates restrained eating (EB-RE) which assesses trying to avoid eating. The questions are ranked on a 5-point Likert scale scored as “0 = never”, “1 = seldom”, “2 = sometimes”, “3 = often”, and “4 = frequently”. In the sub-domains of DEBQ, the increments in the score from 0 to the maximum score means as form not eating in response to emotions to overeating due to an emotional state such as nervousness, happiness, or excitement for EB-EE, not paying any attention to these stimuli and only eat when they are really hungry to eating in response to stimuli such as color, smell and taste of food for EB-ES, and not avoid eating to avoid eating in EB-RE34. To determine the participant’s score for each sub-domain, the mean score for the sub-domain was calculated using the sum of scores earned for questions divided by the number of questions in the sub-domain.

In the last section of the online form, the information related to body image concerns was evaluated by the Body Image Concern Inventory (BICI)35. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire were previously confirmed by Pooravari et al.36. This questionnaire is a 5-point Likert type that contains 19 questions with the answers and scores of “never = 1”, “seldom = 2”, “sometimes = 3”, “often = 4”, and “frequently = 5”. The total score of the questionnaire varies from 19 to 95. A score of 19–37 indicates none or very low concern about body image, a score of 38–52 indicates low concern about body image, a score of 53–69 indicates moderate concern about body image, and a score of 70 and above indicates a high concern of body image36. The BICI also assesses body image in two sub-domain dissatisfaction and embarrassment of one's appearance, checking and hiding perceived defects (BI—dissatisfaction), and the degree to which anxiety about appearance interferes with a person's social performance (BI—social performance).

Statistical analyses

The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative data with normal distribution were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) and were compared using an independent sample t-test between genders. For the independent sample t-test, t (df) and effect size (Cohen’s d) were reported. Cohen’s d value is interpreted as small, medium, and large effect size considering 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 thresholds37,38. Qualitative variables were reported as frequency and percentage and were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test in the case of cells with expected counts less than 539. For the chi-square test, χ2 (df), and for Fisher’s exact test, Fisher’s value were reported. For 2 × 2 categorical variable analysis, φ statistics, and for analyzing variables with more than two categories, Cramer’s V were reported39.

Internal consistency of each scale and sub-domains of each questionnaire were assessed in the study population using Cronbach’s α test. Cronbach’s α > 0.7 is considered an acceptable internal consistency40. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20. Mplus software (version 6) was used to run a path analysis which is a subset of structural equation modeling. A single approach path analysis with a bootstrap approach was run in order to assess the direct and indirect associations of social media addiction with eating behavior through body image concern in the total population. We conducted a multi-group path analysis investigating direct and indirect associations between social media addiction, EB-EE, EB-ES, and EB-RE through BI. To evaluate gender differences we repeated multi-group path analysis with an assumption of equality in coefficient in both genders. The model was properly fitted to data based on the model fit criteria proving that our assumption of equality was valid. Gender, age, network job, being the admin of any social media pages, PAL, BMI, and SES were entered in the multivariate model as potential confounders. To indicate any linkages between variables of interest, path coefficients were reported which are standardized versions of linear regression weights in the structural equation modeling approach. The root means square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were calculated to check the model fit. The values for CFI and TLI > 0.95 and RMSEA < 0.06 are considered to be acceptable41. According to the well-defined clinical correlation between study variables including AD, BI, and EB subclasses, the path analysis was conducted as a full model and all pairwise correlations were considered. Therefore, reporting model fit criteria were not necessary for fully fitted models42. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

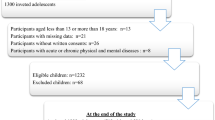

During the time that the link of the online questionnaire was active, 1492 unique IPs viewed the questionnaire description (the front page), and of these, 1214 individuals completed the questionnaire which corresponds to an 81.37% response rate. Based on the answer to the question on the use of psychiatric medications, 244 respondents were excluded, 78 individuals did not answer the question and 166 stated using these medications. Finally, 970 subjects (44.2% girls and 55.8% boys) were included in the analysis. The mean age of the included participants was 17.99 ± 2.53 years (18.34 ± 2.42 and 17.55 ± 2.60 years for boys and girls, respectively, t (887.75) = 4.80, Cohen’s d = 0.31 [medium effect], P < 0.001). BMI of the participants were 22.61 ± 5.05 kg/m2 (22.95 ± 5.24 and 22.18 ± 4.74 kg/m2 for boys and girls respectively, t (968) = 2.36, Cohen’s d = 0.15 [small effect], P = 0.017). Students were the most popular (46.3% for high school and 42.7 for college student) respondents in the study. Regarding diet, 79.2% of the participants reported no special diet, and others reported weight reduction (9.9%), weight gain (3.1%), medical diets (0.2%), and sports diets (7.6%). Boys and girls were unequally distributed in diets (Fisher’s value = 11.90, Cramer’s V = 0.10, P = 0.012). A sedentary lifestyle was declared by 54.0% of the participants, while casual, moderate, and intense exercise was respectively reported by 24.6%, 13.4%, and 7.9%. The distribution of boys and girls in PAL was also significantly different (χ2 (3) = 40.54, Cramer’s V = 0.20, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The CVR for all questions in the Persian version of the SMAS-SF was above 80%. The CVI for relevancy was > 80%, CVI for clarity was > 70% and the CVI for simplicity was > 80% for all questions. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.87 (P value < 0.001) between the results of 3 weeks of test–retest. Cronbach's α was yielded to be 0.92 for the overall SMAS-SF. The sub-domains Cronbach’s α resulted in acceptable internal consistency (virtual tolerance: 0.80, virtual communication: 0.83, virtual problem: 0.86, and virtual information: 0.76).

The analysis showed desirable internal consistency of the BICI questionnaire (Cronbach's α for total = 0.94, BI-dissatisfaction = 0.90, and BI-social performance = 0.88). In the sub-domains of DEBQ Cronbach’s α was 0.88, 0.91, and 0.79, for EB-EE, EB-ES, and EB-RE, respectively.

Table 2 summarizes the social media addiction, body image, and eating behavior status of the total population as well as scores among genders. Total scores for social media addiction was 82.83 ± 19.99 and it was significantly higher in girls compared to boys (t (968) = − 3.43, Cohen’s d = 0.22 [medium effect], P = 0.001). Besides girls had significantly higher scores in subclasses of social media addiction such as virtual tolerance (t (877.96) = − 4.06, Cohen’s d = 0.26 [medium effect], P < 0.001), virtual communication (t (968) = − 3.96, Cohen’s d = 0.25 [medium effect], P < 0.001) and virtual problem (t (968) = − 2.67, Cohen’s d = 0.17 [small effect], P = 0.008). The body image concern score was 86.56 ± 17.92. Compared to boys, girls had higher scores in the subscale of BI-dissatisfaction (t (881.35) = − 2.10, Cohen’s d = 0.13 [small effect], P = 0.035). Also, 37.1% of the participants reported none or very low body image concern and 12.5% of the participants reported a high level of body image concern. The mean scores of emotional eating, external eating, and restrained eating were 2.44 ± 0.90, 3.24 ± 0.74, and 2.30 ± 0.94, respectively, and there were no significant differences between the two sexes.

Based on the results of path analysis, each unit increment in social media addiction score was associated with 0.484 units (SE = 0.025, P < 0.001) higher score of body image concern.

Table 3 shows the multi-group direct and indirect associations of social media addiction and the body image score with eating behavior. The crude multi-group analysis indicates that social media addiction was significantly related to deteriorated eating behavior both directly and indirectly, except direct link with restrained eating which was not statistically significant (β = − 0.014, SE = 0.035, P = 0.687). Besides, the body image concern showed a statistically significant association with eating behavior. The direct, indirect, and total associations of multi-group paths analysis between social media addiction, body image, and eating behavior is depict in Fig. 2.

Multi-group path analysis of direct, indirect and total associations between social media addiction, body image, and eating behavior. *β = 0.069, P < 0.001; **β = 0.065, P < 0.001; ***β = 0.136, P < 0.001; #β = 0.102, P = 0.004; ##β = 0.172, P < 0.001; ###β = − 0.014, P = 0.687; †β = 0.170, P < 0.001; ††β = 0.237, P < 0.001; †††β = 0.122, P < 0.001.

Table 4 shows the multi-group direct and indirect associations of social media addiction and the body image score with eating behaviors’ based on gender. Considering the equality in coefficients for genders, the model was properly fitted to data (RMSEA = 0.030, CFI = 0.995, and TLI = 0.968). Based on the results of path analysis, each unit increment in social media addiction score was associated with a higher score of body image concern (β = 0.433, SE = 0.025, P < 0.001). In both genders, social media addiction was associated with worsened eating behavior both directly and indirectly through body image. The result was not significant for the direct association of social media addiction on EB-RE (β = − 0.001, SE = 0.002, P = 0.691, for both genders).

Table 5 indicates the direct associations of variables with body image and eating behavior. Social media addiction (β = 0.460, SE = 0.026, P < 0.001) and BMI (β = 0.216, SE = 0.028, P < 0.001) were associated with body image scores. EB-EE was related to social media addiction (β = 0.123, SE = 0.036, P = 0.001), body image (β = 0.132, SE = 0.036, P < 0.001), having network job (βyes/no = 0.075, SE = 0.032, P = 0.019), and BMI (β = 0.067, SE = 0.033, P = 0.040). Social media addiction (β = 0.167, SE = 0.036, P < 0.001), body image (β = 0.153, SE = 0.036, P < 0.001), BMI (β = − 0.073, SE = 0.033, P = 0.025) and being semi-affluence compared to deprived (β = 0.115, SE = 0.039, P = 0.003) were recognized as associated variables with EB-ES. Body image (β = 0.241, SE = 0.033, P < 0.001), age (β = − 0.080, SE = 0.030, P = 0.008), BMI (β = 0.275, SE = 0.030, P < 0.001), and physical activity (β = 0.125, SE = 0.030, P < 0.001) and being semi-affluence compared to deprived (β = − 0.098, SE = 0.036, P = 0.007) associated with EB-RE. One unit increment in social media addiction score was associated with a 0.184 unit higher score for emotional eating (SE = 0.032, P < 0.001) [β = 0.123, SE = 0.036, P = 0.001 for direct and β = 0.061, SE = 0.017, P < 0.001 for indirect effects], 0.237 units for external eating (SE = 0.031, P < 0.001) [β = 0.167, SE = 0.036, P < 0.001 for direct and β = 0.070, SE = 0.017, P < 0.001 for indirect effects], and 0.140 units for restrained eating (SE = 0.031, P < 0.001) [β = 0.029, SE = 0.034, P = 0.390 for direct and β = 0.111, SE = 0.017, P < 0.001 for indirect effects].

Discussion

Social networking platforms have become the main routes of communication in most countries. This means of communication has several advantages but also has potential threats13. The present cross-sectional study determined the direct and indirect associations of social media addiction with eating behavior in adolescents and young adults. Based on the study results, both in the crude and adjusted models, social media addiction was significantly associated with higher levels of body image concern, and body image concern was significantly associated with a deteriorated eating behavior in all three subscales of emotional eating, external stimuli, and restrained eating. Moreover, social media addiction was associated with higher scores of emotional eating and external stimuli both directly and indirectly. Multi-group analysis considering genders showed similar results for boys and girls. After adjustment for potential confounders, a similar result was seen. On the other hand, social media addiction did not have significant direct associations with restrained eating, both in the crude and adjusted models. But it was significantly associated with increased scores of restrained eating indirectly through body image concerns.

Adolescence is the most common period for body image concerns15. Body image dissatisfaction especially arises when a teenager compares his or her appearance to a goal that is unattainable and observes a discrepancy with others13. It was previously shown that regular use of highly-visual social media (HVSM) for more than 2 h a day was associated with increased body image concerns in adolescents, in comparison to those with no involvement in HVSM16. In the present study, it was revealed that social media addiction was significantly associated with increased body image concerns in adolescents and young adults. Also, a study by Ho et al.43 revealed that social media comparison with friends and celebrities is associated with adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction and drives them to be thin and muscular in both genders43. When the assessment of individuals’ body image differs from other pictures on social media, individuals are more likely to feel dissatisfied and concerned about their appearance16. A sense of body dissatisfaction prompts individuals to adjust their attitudes and behaviors such as eating behaviors in order to reduce the reality gap44.

The determinants of eating habits are highly complex, especially in adolescents45, including parental care and behavior46,47, peer pressure46, food exposure46, food commercials on media46, food cost48, food availability48, negative self-evaluation45,47, body dissatisfaction45,49, internalization of the thin beauty ideal49, and social media engagement50. From these factors, body dissatisfaction was suggested as an independent predictor of eating disorders51. In the present study, it was shown that body image concern was significantly associated with deteriorated eating behavior in all three subscales of emotional eating, external stimuli, and restrained eating.

Body image dissatisfaction is believed to deteriorate eating behaviors by means of factors including negative emotional status, female gender, peer influence, and early puberty among girls, social and familial factors. These factors lead person to believe being overweight or obese. Thus, despite having a normal weight, person tries to obey weight-reduction diet, and in some cases extreme diets, that consequently initiate eating disorders52. The contents of social media are often a source of comparison for both boys and girls16.

The pooled results of a meta-analysis of 22 studies examining the associations between social media with body image concern and eating habits by Zhang et al.2 revealed a weak but significant positive association between the usage of social network engagement and body image concern as well as disordered eating behavior2. Besides Aparicio-Martinez et al.53 showed that addiction to social network sites is associated with unhealthy eating habits, a thinner body image, and a desire to change part of the body. Acar et al. in 202054, investigated the role of physical appearance comparison in daily life and on social media on eating behaviors in 1384 adolescents. According to their results, more immersion in social media can lead to more physical appearance comparison and disordered eating behaviors in daily life54. In a similar way, Rodgers et al. in 202014 showed the effects of social media engagement on appearance comparison, body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, lower self-esteem, and higher depression among adolescents14. According to their study, appearance comparisons, internalization of the social media ideal, and the muscular ideal appeared as the strongest factor associated with body image concern and restrained eating14. To summarize, as was shown in the present study, social media addiction can be associated with eating habits indirectly through deteriorating body image.

Besides deteriorating eating behavior secondary to increased body image concerns, social media might lead to unhealthy eating habits through different behavioral changes. For example, omitting breakfast in social media users is popular probably through the displacement of other activities. Overspending time on social network sites can result in a lack of time for eating breakfast and an alteration of circadian rhythmicity towards a later midpoint of sleep and subsequent breakfast skipping24. Engagement in social media can disturb the duration and quality of sleep55. Sleep deprivation is associated with insulin resistance, increased hunger, and decreased satiety resulting in unhealthy dietary patterns56. Moreover, social media can affect eating behavior through food advertisements. Social media provide an attractive environment for food marketers to publicize their products, and food advertising plays a significant role in food choices and preferences among young adults24. Results of the present study revealed that social media addiction was associated with increased scores of emotional eating and external stimuli both directly and indirectly. After adjustment for potential confounders, a similar result was seen. It should be noted that in both models, direct relations were more pronounced compared to the indirect association.

The present study had several limitations and strong points. Our cross-sectional design was not able to establish causality. The study was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns. It was seen that lockdowns might lead to mental health issues and consequently change the eating habits of the affected individuals57. Moreover, findings for the effect of psychiatric medication on eating behavior are contradicted58. Thus, to avoid bias in our results and generalizability, we excluded individuals with any history of diagnosed mental disorders or consuming any psychiatric medications, which can limit our findings. In addition, as a limitation of the present study, online data collection may have led to enhanced results in social media addiction scores, since the questionnaire was distributed through social media and the possibility of answering the questionnaire was higher in those who were more dependent on social media. Besides, data on weight and height were self-reported and it might be prone to under/over-reporting biases. Due to the limitations related to the online survey, we had to reduce the number of questions as much as possible, therefore we assessed physical activity level only through one question. Although the online survey led to some limitations, it helped us to include nationwide participants. Moreover, it might have led to more precise answers to social media addiction and body image concern questions. Social media engagement might be in part related to educational or career-related purposes, but the questionnaire used in the present study did not consider those activities. To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to assess the direct and indirect associations of social media addiction on eating behavior through body image concerns.

It is suggested in future studies, the specific content that individuals are exposed in social media be assessed to see how this affects eating behavior. The time spent on social media may be worth assessment. Also, it is suggested that the concurrent effects of nutritional knowledge and food-related social media contents be assessed on eating behavior.

Conclusion

The present study mainly revealed that social media addiction might be associated with eating behavior both directly and also indirectly through deteriorating body image in adolescents and young adults. It is suggested future studies are needed to assess these associations considering the types of social media and the contents participants are faced with through social media.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SE:

-

Standard error

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- BS:

-

Bachelor of Science

- MS:

-

Master of Science

- PAL:

-

Physical activity level

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- SMAS-SF:

-

Social Media Addiction Scale-Student Form

- CVR:

-

Content validity ratio

- CVI:

-

Content validity index

- DEBQ:

-

Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire

- EB-EE:

-

Eating behavior-emotional eating

- EB-ES:

-

Eating behavior-external stimuli

- EB-RE:

-

Eating behavior-restrained eating

- BICI:

-

Body image concern inventory

- BI:

-

Body image

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

- HVSM:

-

Highly-visual social media

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Keser, A., Bayındır-Gümüş, A., Kutlu, H. & Öztürk, E. J. Development of the scale of effects of social media on eating behaviour: A study of validity and reliability. Public Health Nutr. 23(10), 1677–1683 (2020).

Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Li, Q. & Wu, C. J. The Relationship between SNS usage and disordered eating behaviors: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 1, 2 (2021).

Azizi, S. M., Soroush, A. & Khatony, A. J. The relationship between social networking addiction and academic performance in Iranian students of medical sciences: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 7(1), 1–8 (2019).

Nesi, J. J. The impact of social media on youth mental health: Challenges and opportunities. N. C. Med. J. 81(2), 116–121 (2020).

Pirdehghan, A., Khezmeh, E. & Panahi, S. Social media use and sleep disturbance among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Iran. J. Psychiatry 16(2), 137–145 (2021).

Rahman, S. A., et al. Effects of social media use on health and academic performance among students at the university of Sharjah. In 2020 IEEE 44th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); 2020: IEEE.

Ulvi, O. et al. Social media use and mental health: A global analysis. Epidemiologia 3(1), 11–25 (2022).

Sözbilir F, Dursun MK. Does social media usage threaten future human resources by causing smartphone addiction? A study on students aged 9–12. 2018.

Wiederhold, B. K. Tech Addiction? Take a Break Addressing a Truly Global Phenomenon 623–624 (Mary Ann Liebert Inc, 2022).

Rodgers, R. F. & Melioli, T. J. The relationship between body image concerns, eating disorders and internet use, part I: A review of empirical support. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 1(2), 95–119 (2016).

Santarossa, S. & Woodruff, S. J. J. # SocialMedia: Exploring the relationship of social networking sites on body image, self-esteem, and eating disorders. Soc. Media Soc. 3(2), 2056305117704407 (2017).

Carlson Jones, D. J. Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 40(5), 823 (2004).

Latzer, Y., Spivak-Lavi, Z. & Katz, R. J. Disordered eating and media exposure among adolescent girls: The role of parental involvement and sense of empowerment. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 20(3), 375–391 (2015).

Rodgers, R. F. et al. A biopsychosocial model of social media use and body image concerns, disordered eating, and muscle-building behaviors among adolescent girls and boys. J. Youth Adolesc. 49(2), 399–409 (2020).

Rodgers, R. F. The relationship between body image concerns, eating disorders and internet use, Part II: An integrated theoretical model. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 1(2), 121–137 (2016).

Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A. & Settanni, M. Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 82, 63–69 (2018).

Grilo, C. M., Ivezaj, V., Lydecker, J. A. & White, M. A. Toward an understanding of the distinctiveness of body-image constructs in persons categorized with overweight/obesity, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. J. Psychosom. Res. 126, 109757 (2019).

Sabiston, C., Pila, E., Vani, M. & Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Body image, physical activity, and sport: A scoping review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 42, 48–57 (2019).

Sharif, N. et al. The positive impact of social media on health behavior towards the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A web-based cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 15(5), 102206 (2021).

Aldin, K. THE impact of social media on consumers’health behavior towards choosing herbal cosmetics. J. Crit. Rev. 7, 9 (2020).

Yurtdaş-Depboylu, G., Kaner, G. & Özçakal, S. The association between social media addiction and orthorexia nervosa, eating attitudes, and body image among adolescents. Eating Weight Disord. Stud. Anorexia Bulimia Obes. 12, 1–11 (2022).

Ocansey, S. K., Ametepe, W. & Oduro, C. F. The impact of social media on the youth: The Ghanaian perspective. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 3(2), 90–100 (2016).

Nagata, J. M. New findings from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey: Social media, social determinants, and mental health. J. Adolesc. Health 66(6), S1–S2 (2020).

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Chaput, J.-P. & Hamilton, H. A. Associations between the use of social networking sites and unhealthy eating behaviours and excess body weight in adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 114(11), 1941–1947 (2015).

Kamalikhah, T., Bajalan, M., Sabzmakan, L. & Mehri, A. The impacts of excessive use of social media on Iranian Adolescents’ Health: A qualitative study. Middle East J. Rehabil. Health Stud. 8, 4 (2021).

Althunayan, A., Alsalhi, R. & Elmoazen, R. Role of social media in dental health promotion and behavior change in Qassim province, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Health Res. 4(2), 98–103 (2018).

Cato, S. et al. The bright and dark sides of social media usage during the COVID-19 pandemic: Survey evidence from Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduction 54, 102034 (2021).

Nevitt, J. & Hancock, G. R. Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 8(3), 353–377 (2001).

Wendel-Vos, W., Droomers, M., Kremers, S., Brug, J. & Van Lenthe, F. Potential environmental determinants of physical activity in adults: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 8(5), 425–440 (2007).

Safarpour, M. et al. Prevalence and outcomes of food insecurity and its relationship with some socioeconomic factors. Knowl. Health 8(4), 193–198 (2014).

Sahin, C. Social media addiction scale-student form: The reliability and validity study. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 17(1), 169–182 (2018).

Lawshe, C. H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 28(4), 563–575 (1975).

Halvarsson, K. & Sjödén, P. O. J. Psychometric properties of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ) among 9–10-year-old Swedish girls. Eur. Eating Disord. Rev. 6(2), 115–125 (1998).

Kargar, M., Sabet Sarvestani, R., Tabatabaee, H. R. & Niknami, S. The assessment of eating behaviors of obese, over weight and normal weight adolescents in Shiraz, Southern Iran. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 1(1), 35–42 (2013).

Littleton, H. L., Axsom, D. & Pury, C. L. Development of the body image concern inventory. Behav. Res. Ther. 43(2), 229–241 (2005).

Pooravari, M., Habibi, M., Parija, H. A. & Tabar, S. H. Psychometric properties of body image concern inventory in adolescent. Pajoohandeh J. 19(4), 189–199 (2014).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Routledge, 2013).

Sullivan, G. M. & Feinn, R. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 4(3), 279–282 (2012).

Armitage, P., Berry, G. & Matthews, J. N. S. Statistical Methods in Medical Research (Wiley, 2008).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 314(7080), 572 (1997).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 9(2), 233–255 (2002).

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 8(2), 23–74 (2003).

Ho, S. S., Lee, E. W. & Liao, Y. Social network sites, friends, and celebrities: The roles of social comparison and celebrity involvement in adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction. Soc. Media Soc. 2(3), 2056305116664216 (2016).

Hamel, A. E., Zaitsoff, S. L., Taylor, A., Menna, R. & Grange, D. L. Body-related social comparison and disordered eating among adolescent females with an eating disorder, depressive disorder, and healthy controls. Nutrients 4(9), 1260–1272 (2012).

Reijonen, J. H., Pratt, H. D., Patel, D. R. & Greydanus, D. E. Eating disorders in the adolescent population: An overview. J. Adolesc. Res. 18(3), 209–222 (2003).

Ray, J. W. & Klesges, R. C. Influences on the eating behavior of children. 699(1), 57–69 (1993).

Fairburn, C. G. et al. Risk factors for binge eating disorder: A community-based case–control study. Arch. Gener. Psychiatry 55(5), 425–432 (1998).

Kabir, A., Miah, S. & Islam, A. Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. PLoS One 13(6), e0198801 (2018).

Stice, E., Marti, C. N. & Durant, S. Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther. 49(10), 622–627 (2011).

Jordan, A. B., Kramer-Golinkoff, E. K. & Strasburger, V. C. Does adolescent media use cause obesity and eating disorders. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 19(3), 431–449 (2008).

Levine, M. P. & Piran, N. The role of body image in the prevention of eating disorders. Body Image 1(1), 57–70 (2004).

Littleton, H. L. & Ollendick, T. Negative body image and disordered eating behavior in children and adolescents: What places youth at risk and how can these problems be prevented?. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 6(1), 51–66 (2003).

Aparicio-Martinez, P. et al. Social media, thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes: An exploratory analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(21), 4177 (2019).

Acar, M. et al. Eating attitudes and physical appearance comparison with others in daily life versus on social media in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 66(2), S59–S60 (2020).

Domoff, S. E., Sutherland, E. Q., Yokum, S. & Gearhardt, A. N. Adolescents’ addictive phone use: Associations with eating behaviors and adiposity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(8), 2861 (2020).

Bhurosy T, Thiagarajah K. Are eating habits associated with adequate sleep among high school students? 2020;90(2):81–7.

Robinson, E. et al. Obesity, eating behavior and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: A study of UK adults. Appetite 156, 104853 (2021).

MacNeil, B. A. & Thib, S. Psychiatric medication use by Canadian adults prior to entering an outpatient eating disorders program: Types and combinations of medications, predictors of being on a medication, and clinical considerations. Psychiatry Res. 317, 114930 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank all adolescents and young adults who participated in the study. The authors thank the vice-chancellor of Research of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for the financial support of the study. We would like to send our warmest appreciation to Dr. Zahra Bagheri (Associate professor in Biostatistics, Department of Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran) for her kind and dedicated help in the statistical improvement of the study.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 24537).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. and M.A. conceptualized the study. M.K., R.B., M.M. and M.A. prepared online questionnaires and conducted data gathering. M.M. and M.A. performed statistical analyses. M.M., M.K., R.B., G.F. and M.A. prepared the manuscript draft. All authors read and confirmed the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohsenpour, M., Karamizadeh, M., Barati-Boldaji, R. et al. Structural equation modeling of direct and indirect associations of social media addiction with eating behavior in adolescents and young adults. Sci Rep 13, 3044 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29961-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29961-7

- Springer Nature Limited