Abstract

Even when treated comprehensively by surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, soft-tissue sarcoma has an unfavorable outcome. Because soft-tissue sarcoma is rare, it is the subject of fewer clinicopathological studies, which are important for clarifying pathophysiology. Here, we examined tumor-associated macrophages in the intratumoral and marginal areas of sarcomas to increase our knowledge about the pathophysiology. Seventy-five sarcoma specimens (not limited to a single histological type), resected at our institution, were collected, and the number of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages in the intratumoral and marginal areas was counted. We then performed statistical analysis to examine links between macrophage numbers, clinical factors, and outcomes. A high number of macrophages positive for all markers in both areas was associated with worse disease-free survival (DFS). Next, we divided cases according to the FNCLCC classification (Grade 1 and Grades 2/3). In the Grade 1 group, there was no significant association between macrophage number and DFS. However, in the Grade 2/3 group, high numbers of CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area were associated with poor DFS. By contrast, there was no significant difference between the groups with respect to high or low numbers of CD68-, CD163-, or CD204-positive macrophages in the intratumoral area. Multivariate analysis identified the number of CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area as an independent prognostic factor. Macrophage numbers in the marginal area of soft-tissue sarcoma may better reflect clinical behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soft-tissue sarcoma is relatively rare compared with other cancers; therefore, there are problems related to diagnosis and treatment. Generally, although high-grade soft-tissue sarcomas can be managed by comprehensive treatment (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy), they often recur. Thus, our knowledge about tumorigenesis and progression must improve if we are to obtain better treatment outcomes. Soft-tissue sarcomas are differentiated into various tissues with different clinicopathological features and genomic status. This makes clarifying the pathophysiology complicated. Here, we focus on the tumor microenvironment of sarcoma, rather than the sarcoma itself.

The tumor microenvironment comprises various tissues and cell types, including immune cells (e.g., macrophages), endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes. Recently, the role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which contribute to development and progression of cancer, has received much attention. Upon stimulation with various factors, macrophages are induced to differentiate into an M1 or an M2 phenotype, each of which plays a different role. Toll-like receptor ligands, lipopolysaccharide, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF induce M1 macrophages (referred to as classically activated macrophages), which (generally) play a pro-inflammatory/antitumor role1,2,3. By contrast, cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment, along with IL4, IL10, IL13, transforming growth factor beta (TGF), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), induce M2 macrophages or TAMs, which promote tumor progression by secreting growth factors, adhesion factors, and cytokines1,2,3,4,5,6. M1 macrophages and TAMs (M2) can be distinguished by immunophenotyping. Typically, CD68 and Iba1 are pan-macrophage markers, whereas CD163 and CD204 are TAM-specific markers7,8,9. Many studies report that TAMs play a pro-tumorigenic role by forming a cancer-promoting inflammatory microenvironment10,11,12; they do this by exerting immunosuppressive effects12,13,14, and by promoting angiogenesis15,16 and metastasis17,18,19. In fact, many clinicopathological studies of various cancers show that aggressive invasion by macrophages is associated with a poor prognosis20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. By contrast, fewer studies have investigated the clinicopathological significance of macrophages present in sarcomas.

Previously, we examined the role of TAMs and found that they transfer cancer-derived components to stromal cells to establish a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment28. Fibroblasts exposed to cancer-derived components differentiate into cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-like cells in the marginal area, which then form a pro-tumoral microenvironment. We hypothesized that macrophages play a role in the transfer of cancer-derived components to marginal stromal cells, and that this contributes to enlargement of the tumor microenvironment. Accordingly, macrophages in the marginal area may play a role equally important to that of macrophages in the intratumoral area, and this may also be true for sarcomas. In this study, we subjected surgical specimens of 75 soft-tissue sarcomas to immunohistochemical examination and counted the number of the infiltrating CD68-positive macrophages (total macrophages) and CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages (TAMs). We counted each type in the intratumoral area and marginal area (the non-sarcoma area adjacent to the sarcoma) and examined the association between macrophage numbers and various clinical factors.

Materials and methods

Case collection

Seventy-five cases of soft-tissue sarcoma, evaluated according to the FNCLCC grading system, were enrolled. These cases were managed at Akita University Hospital (Akita, Japan) between 2004 and 2017. The general characteristics of the 75 patients are shown in Table 1. No patients received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and all underwent marginal or extended resection. The clinicopathological characteristics were obtained from clinical records; however, some cases were re-diagnosed according to the current WHO pathological classification (5th edition) due to changes in classification, terms, and criteria over the last 20 years. Collected histological subtypes included well-differentiated liposarcoma, myxoid liposarcoma, round cell liposarcoma, dedifferentiated liposarcoma, pleomorphic liposarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, conventional leiomyosarcoma, poorly differentiated leiomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Disease-free survival (DFS) was measured from the date of surgery to the date of recurrence or the date when the patient was last known to be disease-free. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Akita University, Graduate School of Medicine (Reference No. 2652). Informed consent was obtained in the form of opt-out on the website. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissue sections (thickness: 4 μm) were cut and stained by a Ventana Discovery XT autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA). The staining antibodies were: mouse monoclonal anti-human CD68 (Clone PG-M1, 1:100; Dako, Japan), a pan-macrophage marker, anti-mouse/rat /human CD163 (Clone EPR19518, 1:500, abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-human CD204 (Clone SRA-E5, 1:500; Trans Genic Inc., Japan), a TAM marker.

IHC evaluation

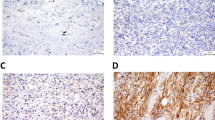

All IHC slides were scanned at an absolute magnification of 20 × using a pathology digital imaging system (Nanozoomer virtual slide system, Hamamatsu Photonics, Shizuoka, Japan). For each slide, five representative fields (0.2 mm2) containing intratumoral and marginal areas were selected, and the number of positive cells was counted manually (Fig. 1a). The selected intratumoral and marginal areas were almost same for the CD68, CD163, and CD204-stained slides. The marginal area is the non-sarcoma area adjacent to the sarcoma. For most sarcomas, the histological findings identified a non-sarcomatous area bordering the sarcomatous area, which was designated as the “marginal area”. In cases where the border between sarcoma and non-sarcoma was unclear, we carefully distinguished atypical cells from preexisting tissue, and designated the non-sarcoma area around the sarcoma margin as the “marginal area”. The total number of CD68-, CD163-, or CD204-positive cells in the five tumor fields was recorded (Fig. 1b,c). There were two cases in which the marginal specimen did not include normal tissue; in these cases, the marginal tumor area was used instead of the marginal normal area. Both cases involved an atypical lipomatous tumor.

Statistical analysis

Shapiro–Wilk test showed the number of macrophages are not normal distribution, therefore, the non-parametric analyses described below were performed. The number, distribution, and type of macrophage was assessed using the Friedmann rank sum test with Bonferroni correction, and the Wilcoxon signed rank test (Table 2). The correlation between the number of intratumoral/marginal macrophages of each phenotype was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis (Fig. 2). Clinical factors and macrophage type were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test, the Kruskal–Wallis test, and the Steel–Dwass test (Table 3, Fig. 3). The log-rank test and a Cox proportional hazards regression model were also used. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University), which is based on R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.1.2), and R commander29. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant. Correlation coefficients between 0.4 and 0.7 were defined as intermediate, whereas those > 0.7 were defined as strong.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Akita University, Faculty of Medicine, Ethics Committee (Reference No. 2652).

Patient consent status

Informed consent was obtained in the form of opt-out on the website.

Results

Distribution of each macrophage phenotype, and the correlation between intratumoral and marginal macrophages of each phenotype in soft-tissue sarcoma

The number of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages in the intratumoral and marginal areas of 75 soft-tissue sarcoma specimens was counted. A comparison of macrophage numbers in the intratumoral and marginal areas revealed that the number expressing each of these markers was significantly higher in the intratumoral area than in the marginal area (CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.00000109, p = 0.000013, and p = 0.00000711, respectively) (Table 2). For each particular marker, there was an intermediate correlation between the numbers in the marginal and intratumoral areas (CD68-positive macrophages: r = 0.575; CD163-positive macrophages: r = 0.644; CD204-positive macrophages: r = 0.618; p < 0.001 for all) (Fig. 2a–c).

By contrast, a comparison of the number of macrophages expressing each type of marker revealed that the number of CD163-positive macrophages in both areas was significantly lower than that of CD68- and CD204-positive macrophages (intratumoral area: p = 0.000233; marginal area: p = 0.00000283) (Table 2). In both areas, there was an intermediate-to-strong correlation between the number of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages in each examined area (intratumoral CD68- and intratumoral CD163-positive macrophages: r = 0.907; intratumoral CD68- and intratumoral CD204-positive macrophages: r = 0.876; intratumoral CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages; r = 0.86; marginal CD68- and CD163-positive macrophages: r = 0.697; marginal CD68- and CD204-macrophages: r = 0.804; marginal CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages; r = 0.72; p < 0.001 for all) (Fig. 2d–i).

Association between the number of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages in each area and clinical factors

The number of each type of marker-positive macrophage in both areas of the tumor, and their association with clinical factors, was analyzed statistically (Table 3). Sex, age, tumor size, or location had no effect on the type of marker-positive macrophage either area. However, there were significant differences among FNCLCC grades (Fig. 3). For almost all combinations of marker and area, post-hoc analysis revealed that the number of macrophages in Grade 1 cases was significantly lower than that in Grade 2 and 3 cases (Grade 1 vs. Grade 2 and Grade 1 vs. Grade 3 for intratumoral CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages; Grade 1 vs. Grade 3 for marginal CD 68-positive macrophages; Grade 1 vs. Grade 2 and Grade 1 vs. Grade 3 for marginal CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages; all p < 0.05. Grade 1 vs. Grade 2 for marginal CD68-positive macrophages; p = 0.09105). However, we found a significant difference between Grade 2 and Grade 3 with respect to the number of CD163-positive macrophages in the marginal area (p < 0.05). Although there was no significant difference in the number of intratumoral CD163-positive macrophages, intratumoral CD204-positive macrophages, and marginal CD204-positive macrophages between Grades 2 and 3, the overall number of macrophages in Grade 3 cases tended to be higher than that in Grade 2 cases (intratumoral CD68-positive macrophages: p = 0.4272; intratumoral CD163-positive macrophages: p = 0.08728, intratumoral CD204-positive macrophages; p = 0.5561, marginal CD68-positive macrophages; p = 0.2422, marginal CD204-positive macrophages; p = 0.1076).

Association between the number of macrophages in the intratumoral and marginal areas and DFS

Next, we performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis of the groups with a high and low number of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages in both tumor areas. All cases with high macrophage counts in both areas, showed significantly worse DFS than those with low counts (intratumoral CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.00595, p = 0.0178, and p = 0.00116, respectively; marginal CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.0108, p = 0.0000735, and p = 0.0000011, respectively) (Fig. 4). Next, we divided the population into two subgroups (FNCLCC Grade 1 and FNCLCC Grades 2/3), and analyzed DFS. In the Grade 1 group, high numbers of CD68- and CD204-positive macrophages in both areas tended to be associated with worse DFS (intratumoral CD68- and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.189 and p = 0.362, respectively; marginal CD68- and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.252 and p = 0.64 respectively) (Fig. 5), although the results did not reach the threshold for significance. In the Grade 2/3 group, there was no significant difference between them with respect to the phenotype of macrophage in the intratumoral area; however, high numbers of CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area were associated with significantly worse DFS (marginal CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.0139 and p = 0.00844, respectively) (Fig. 6). We also assessed metastasis-free survival in patients with Grade 2/3 sarcoma (Fig. 7). High numbers of CD68-, CD163-, or CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area were associated with poorer metastasis-free survival (marginal CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.03, p = 0.0305, and p = 0.0254, respectively); however, the number of macrophages (of any phenotype) in the intratumoral area had no significant effect on metastasis-free survival in either group. Finally, we assessed local recurrence-free survival for those with Grade 2/3 sarcoma. Again, the number and phenotype of macrophages in the intratumoral or marginal areas had no significant effect (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online).

Prognostic value of the number of CD163- or CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area

We performed multivariate analysis to analyze the prognostic value of the number of marginal CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages and other clinical factors (sex, age, location, size, and FNCLCC grade; see Table 4) for all cases. Multivariate analysis of DFS identified the numbers of marginal CD163- and CD204- positive macrophages as independent predictors of a poorer prognosis for Grades 1, 2, and 3 (marginal CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages: p = 0.04739 and p = 0.003541, respectively).

Discussion

Compared with cancer in general, sarcoma is quite rare. Furthermore, soft-tissue sarcoma includes many histological types; therefore, it is difficult to collect cases limited to a specific single histological type for statistical analysis. For these reasons, few studies have performed clinicopathological examination of TAMs in sarcoma. Here, we also reviewed previous studies that investigated the association between TAMs and clinical outcomes of patients with soft-tissue sarcoma (Table 5)7,30,31,32,33,34. Most previous studies report that high macrophage counts are associated with poor outcomes; however, some do not show a significant association between TAMs and clinical outcome. Also, none of these studies evaluated macrophages in the marginal area, as we did here.

We collected cases regardless of histology; however, we excluded cases that had undergone preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In the overall population, the macrophage count (all phenotypes) in both areas showed a significant association with DFS. These results suggest that the number of macrophages in the intratumoral or marginal area is associated with the clinical grade of sarcoma. This is supported by our finding that the number of macrophages, especially CD163- or CD204-positive macrophages, in the intratumoral or marginal area was associated with FNCLCC grade (Fig. 3). In the Grade 1 subgroup, high numbers of CD68- and CD204-positive macrophages tended to be associated with a poorer prognosis, although there was no significant difference between macrophage numbers in the two areas. We think that if the number of cases had been larger, we may have found a significant difference. Interestingly, we found that patients in the Grade 2/3 subgroup with high numbers of CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area showed significantly poorer DFS; this association was not present when we examined the intratumoral area. The finding that high numbers of intratumoral macrophages (CD68-positive, CD163-positive, or CD204-positive) tended to be associated with somewhat poorer DFS is consistent with previous studies. To evaluate DFS, we defined local recurrence and metastasis as a clinical event. We considered that local recurrence depends somewhat upon the surgical method (marginal or extensive resection); thus, we also assessed metastasis-free survival in those with Grade 2/3 sarcoma. We found that those with high numbers of macrophages in the marginal area showed poorer outcomes (as was observed for DFS). Multivariate analysis identified a high number of CD163- or CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area as an independent prognostic factor.

We suggest three explanations for the above results. One involves the types of cases that were enrolled in the study. Unlike previous studies, our cases were of various histological type. The pathological characteristics and clinical behavior of sarcomas differ among histological types, which may be one reason for the differences in the results. Second, the accuracy of the macrophage counts should be considered. In cases of high-grade sarcoma, especially undifferentiated sarcoma, the sarcoma cells themselves are sometimes CD68-positive. Actually, almost all cases diagnosed as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma today may have been previously diagnosed as malignant fibrous histiocytoma. We did not find an sarcoma cells that were CD163- and CD204-positive; however, the possibility that some were CD163- or CD204-positive cannot be ruled out (indeed, a case of CD163-positive sarcoma has been reported35). In addition, high-grade sarcomas often show dense infiltration of the intratumoral area by CD68-/CD163-/CD204-positive cells, as demonstrated in Fig. 1c. These findings make precise counting of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive cells very difficult; thus, the number of macrophages in the intratumoral area may not be precise. In turn, the number of macrophages in the marginal area, which was lower than that in the intratumoral area, was easier to count because the macrophages were easier to distinguish from sarcoma cells. Of course, quantification of the macrophages in the marginal area was also associated with some problems. One such problem occurs in cases involving marginal resection. Some cases, especially low-grade sarcoma (e.g., atypical lipomatous tumors) are treated by marginal resection. In this study, we carefully analyzed small amounts of the non-sarcoma (i.e., normal) area adjacent to the sarcoma and counted the number of macrophages in those areas. However, in cases in which we could not find a marginal normal area, the marginal tumor area was investigated instead. Another problem is that there were cases with an unclear demarcation line. In such cases, we carefully chose the area to analyze, making sure not to count sarcoma cells. Despite these problems, for Grade 2/3 sarcomas, the number of the macrophages in the marginal area show a stronger correlation with prognosis than the number in the intratumoral area. Lastly, marginal macrophages may play an important role in sarcoma progression. As we described earlier, macrophages play an important role in formation of the tumor microenvironment in gastric cancer28. If this is the same for sarcoma, then the number of macrophages in the marginal area may reflect the clinicopathological behavior of the sarcoma.

Biomolecular studies are needed to confirm the hypothesis that macrophages in the marginal area play an important role in progression of sarcoma. Similar to other studies, the results of the present study suggest that there are therapeutic benefits in targeting macrophages as a treatment for sarcoma36.

Conclusion

We investigated the numbers of CD68-, CD163-, and CD204-positive macrophages in the intratumoral and marginal areas of sarcoma cases. In all cases (Grade 1/2/3), we found that patients with high numbers of intratumoral macrophages (CD68 + , CD163 + , and CD204 +) and high numbers of marginal macrophages (CD68 + , CD163 + , and CD204 +) showed poor DFS. In Grade 2/3 cases, those with high numbers of CD163- and CD204-positive macrophages in the marginal area showed a poorer prognosis than those with low numbers, whereas there was no significant difference in prognosis of those with high and low numbers of CD68-, CD163-, or CD204-positive macrophages in the intratumoral area.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article.

References

Malfitano, A. M. et al. Tumor-associated macrophage status in cancer treatment. Cancers (Basel). 12, 1–25 (2020).

Van Dalen, F. J., Van Stevendaal, M. H. M. E., Fennemann, F. L., Verdoes, M. & Ilina, O. Molecular repolarisation of tumour-associated macrophages. Molecules 24, (2019).

Fujiwara, T. et al. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in sarcomas. Cancers (Basel). 13, 1–17 (2021).

Wang, J., Li, D., Cang, H. & Guo, B. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: Role of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Med. 8, 4709–4721 (2019).

Saeedifar, A. M., Mosayebi, G., Ghazavi, A., Bushehri, R. H. & Ganji, A. Macrophage polarization by phytotherapy in the tumor microenvironment. Phyther. Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7058 (2021).

Malekghasemi, S. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: Protumoral macrophages in inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 10, 556–565 (2020).

Komohara, Y. et al. Positive correlation between the density of macrophages and T-cells in undifferentiated sarcoma. Med. Mol. Morphol. 52, 44–51 (2019).

Kovaleva, O. V., Samoilova, D. V., Shitova, M. S. & Gratchev, A. Tumor Associated Macrophages in Kidney Cancer. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2016, (2016).

Yamate, J., Izawa, T. & Kuwamura, M. Histopathological analysis of rat hepatotoxicity based on macrophage functions: In particular, an analysis for thioacetamide-induced hepatic lesions. Food Saf. 4, 61–73 (2016).

Noguchi, M., Hiwatashi, N., Liu, Z. & Toyota, T. Secretion imbalance between tumour necrosis factor and its inhibitor in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 43, 203–209 (1998).

Tselepis, C. et al. Tumour necrosis factor-α in Barrett’s oesophagus: A potential novel mechanism of action. Oncogene 21, 6071–6081 (2002).

Capece, D. et al. The inlammatory microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: A pivotal role for tumor-Associatedmacrophages Daria. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, (2013).

Spear, P., Barber, A., Rynda-Apple, A. & Sentman, C. L. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells shape myeloid cell function within the tumor microenvironment through IFN-γ and GM-CSF. J. Immunol. 188, 6389–6398 (2012).

Werno, C. et al. Knockout of HIF-1α in tumor-associated macrophages enhances M2 polarization and attenuates their pro-angiogenic responses. Carcinogenesis 31, 1863–1872 (2010).

Stockmann, C. et al. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor in myeloid cells accelerates tumorigenesis. Nature 456, 814–818 (2008).

Baer, C., Squadrito, M. L., Iruela-Arispe, M. L., & Palma, M. De. Reciprocal interactions between endothelial cells and macrophages in angiogenic vascular niches. Physiol. Behav. 319, 1626–1634 (2013).

Pignatelli, J. et al. Invasive breast carcinoma cells from patients exhibit MenaINV -and macrophage-dependent transendothelial migration. Sci. Signal. 7, ra112 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3. Cancer Cell 19, 541–555 (2011).

Dan, I. et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein regulates leukocyte- dependent breast cancer metastasis. Cell Rep. 4, 129–136 (2013).

Fujimoto, J., Aoki, I., Khatum, S., Toyoki, H. & Tamaya, T. Clinical implications of expression of interleukin-8 related to myometrial invasion with angiogenesis in uterine endometrial cancers. Ann. Oncol. 13, 430–434 (2002).

Kurahara, H. et al. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Res. 167, e211–e219 (2011).

Hu, W. et al. Alternatively activated macrophages are associated with metastasis and poor prognosis in prostate adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 10, 1390–1396 (2015).

Shibutani, M. et al. The peripheral monocyte count is associated with the density of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer 17, 1–7 (2017).

De la Fuente López, M. et al. The relationship between chemokines CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4 with the tumor microenvironment and tumor-associated macrophage markers in colorectal cancer. Tumor Biol. 40, 1–12 (2018).

Kawachi, A. et al. Tumor-associated CD204+ M2 macrophages are unfavorable prognostic indicators in uterine cervical adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 109, 863–870 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages regulate gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis through TGFβ2/NF-κB/Kindlin-2 axis. Chinese J. Cancer Res. 32, 72–88 (2020).

Xue, T. et al. Prognostic significance of CD163 + tumor- associated macrophages in colorectal cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 19, 186 (2021).

Umakoshi, M. et al. Macrophage-mediated transfer of cancer-derived components to stromal cells contributes to establishment of a pro-tumor microenvironment. Oncogene 38, 2162–2176 (2019).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48, 452–458 (2013).

Lee, C. H. et al. Prognostic significance of macrophage infiltration in leiomyosarcomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1423–1430 (2008).

Ganjoo, K. N. et al. The prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophages in leiomyosarcoma: A single institution study. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 82–86 (2011).

Nabeshima, A. et al. Tumour-associated macrophages correlate with poor prognosis in myxoid liposarcoma and promote cell motility and invasion via the HB-EGF-EGFR-PI3K/Akt pathways. Br. J. Cancer 112, 547–555 (2015).

Oike, N. et al. Prognostic impact of the tumor immune microenvironment in synovial sarcoma. Cancer Sci. 109, 3043–3054 (2018).

Shiraishi, D. et al. CD163 is required for protumoral activation of macrophages in human and murine sarcoma. Cancer Res. 78, 3255–3266 (2018).

Sarode, S. C. et al. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the mandible – A case report and review of published case reports. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 9, 221–225 (2019).

Ozaniak, A. et al. A novel anti-CD47-targeted blockade promotes immune activation in human soft tissue sarcoma but does not potentiate anti-PD-1 blockade. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04292-8 (2022).

Funding

The research was funded by JSPS Kakenhi Grants (Number 21K15380 to MU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived and designed the study. M.U., A.N., and Y.K-A. prepared materials, and collected and analyzed the data; M.U. and A.N. wrote the manuscript; Z.L., M.T., and A.G. conceptualized the study; H.T., H.N., H.N., and N.M. provided patient samples and materials; K.M., Y.I., M.Y., and D.M. carried out the experiments. This study was supervised by K.O., M.T., and A.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Umakoshi, M., Nakamura, A., Tsuchie, H. et al. Macrophage numbers in the marginal area of sarcomas predict clinical prognosis. Sci Rep 13, 1290 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28024-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28024-1

- Springer Nature Limited