Abstract

In recent decades, variability in the incidence and mortality of kidney cancer (KC) has been reported. This study aimed to compare trends in incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) of KC between the European Union (EU) 15 + countries and 6 World Health Organization (WHO) regions. The data of KC Age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs), age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs), and age-standardized DALYs were extracted from the Global Burden of Disease database. Joinpoint regression was employed to examine trends. From 1990 to 2019, the ASIR increased in most countries except for Luxembourg (males), the USA (females) and Austria and Sweden (both sexes). ASIR increased across all 6 WHO regions for both sexes except for females in Americas. The ASMR increased in 10/19 countries for males and 9/19 for females as well across most WHO regions. The mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) decreased in all countries and WHO regions. Trends in DALYs were variable across countries and WHO regions. While the incidence and mortality from KC rose in most EU15 + countries and WHO regions from 1990 to 2019, the universal drop in MIR suggests an overall improvement in KC outcomes. This is likely multifactorial, including earlier detection of KC and improved treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kidney Cancer (KC) is ranked among the most common cancers diagnosed worldwide and is increasing in incidence1. In 2020, around 400,000 new diagnoses of KC were estimated worldwide, with 180,000 estimated deaths2. The main histologic type of KC is renal cell carcinoma (RCC), accounting for 90% of the incident cases and most of the KC morbidity and deaths3. Subtypes of RCC include clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe histology in 70%, 15%, and 5% of the cases, respectively4. The strongest risk factors related to KC are age, gender, obesity, smoking, hypertension, and chronic kidney diseases4,5,6,7,8,9.

In recent decades, significant variability in incidence and mortality of KC was noted worldwide5, with an average age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of 4.6 per 100,000 noted in 2020 and an average age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) of 1.8 per 100,00010. The incidence was reported twice higher in males than females and is more common in developed countries than in developing countries10,11. For instance, Northern America had the highest ASIR of 12.2 per 100,000, followed by Northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand (10.3), and Central and Eastern Europe (3.4 per 100,000) had the highest ASMR, followed by Western Europe (2.8), Northern Europe (2.7), and Australia and New Zealand (2.4)10.

While the incidence of KC has been increasing in the past decades, mortality is decreasing in Western Europe and most Northern European countries and the United States of America (USA) and Australia11. One possible reason behind the stability of mortality rates would be earlier detection, improved surgical and ablative techniques, and improved systemic treatment options for patients with locally advanced or metastatic RCC12. Furthermore, the ever-increasing use of imaging, including computed tomography (CT) scan, has led to the identification of incidental asymptomatic renal masses. This has resulted in stage migration with detection of earlier stage disease and reductions in mortality rates in American and European regions13,14.

This study aims to compare the trends in KC among countries of the European Union (EU) 15 + cohort and between 6 WHO regions during the period ranging from 1990 to 2019. The following 19 countries are unitedly included in the EU15 + grouping: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom (UK), and the USA. The WHO regions include the African Region (AFR), Region of the Americas (AMR), South-East Asian Region (SEAR), European region (EUR), Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), and Western Pacific Region (WPR). The EU15 + has been previously utilized in comparative analyses of trends in other diseases15,16, as it forms a comparable group of countries. Data were extracted from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study to evaluate the trends in KC mortality, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, in WHO regions, and in the EU15 + countries from 1990 to 2019. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to describe incidence, mortality, and DALYs changes and the analysis of significant trends present in the studied period.

Methods

Characteristics of the data source

This observational analysis of KC among EU15 + countries was performed using data from the GBD database. Previous publications describe the exact GBD methodology in greater detail17,18, and we have used this database to describe trends in peripheral arterial disease16, abdominal aortic aneurysm19, and lower extremity amputation20. Data sets used by the GBD collaborators include insurance, admission, and outpatient encounter data, and published systematic reviews, among others. For KC, the GBD maps all mortality and incidence data related to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (codes C64-C65 and D41.0, D41.1 from ICD-10, and codes 189.1, 189.1 from ICD9). These data are then combined by Bayesian meta-regression with the DisMod-MR 2.19 tool21 that analyses, adjust for bias, and produces disease estimates with uncertainty intervals. GBD has different mappings of ICD codes based on incidence and mortality.

Mortality data is collected from vital registration sources, verbal autopsy reports, and surveillance data and entered the GBD cause-of-death database. The quality of mortality data from each country is rated by the GBD methodology in a 5-star system by location-year to assist in the reader’s comprehension of the reliability of the cause of death data. The EU15 + countries have been previously analyzed this way, with 10 of 19 countries scoring five stars (85–100% completeness of mortality data), and the remaining nine countries scored four stars (65–84% completeness of mortality data).

Handling of the GBD data

We extracted age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs), age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs), and age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for KC from EU15 + countries between 1990 and 2019 using the dedicated GBD Study results tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). Age-standardized rates are used to account for the age structures of each country and are expressed per 100,000 person-years. The method used by the GBD involves calculating a standard population by GBD.

We calculated absolute and relative changes in ASIRs, ASMRs, and DALYs between 1990 and 2019 for each sex in each country and each region. The mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) were calculated by dividing ASMR by ASIR for each year (1990 and 2019) in all EU15 + countries and 6 WHO regions. MIRs compare disease burden by normalizing mortality to incidence, and disability-adjusted life-years incorporate morbidity and mortality figures to calculate the number of years lived with and lost from a disability. The WHO also uses this metric to indicate the overall burden of disease on a health-system11. These measures facilitate our understanding of KC’s varying temporal impact. Global and different WHO region mean trends are also reported for comparison.

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the GBD repository, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Statistical analysis

Joinpoint Command Line Version 4.5.0.1 was used to apply a Joinpoint regression analysis to the incidence, mortality, and DALYs data (provided for free by the United States National Cancer Institute Surveillance Research Program)22. The software observes trends in the data over the time studied and connects these trends with the simplest model possible on a logarithmic scale. It produces periods where significant trend points have been identified. It will identify specific inflection points in the overall trends and provide a robust estimate of each country's changing trends. The simplest model has no Joinpoints and represents a straight line. As more Joinpoints are added, each is tested for significance using a Monte Carlo permutation method. The Joinpoint software also computed an estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) (with 95% confidence intervals) for each Joinpoint line segment and tested for significance. The result of the analyses is a series of statistically significant Joinpoints for each country, with each trend (either positive or negative) represented by a potentially significant EAPC. This allows a thorough assessment of temporal trends and allows for inter-country comparability.

Results

Trends in KC among EU15 + countries were analyzed from 1990 to 2019. Age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates, mortality-incidence ratios, and age-standardized DALYs were compared in this study.

Trends in KC ASIR, 1990–2019

Across the study period, there was a rise in ASIR globally for both males (+ 38.4%) and females (+ 13.5%). There was a similar trend across all six regions, with the Western Pacific region seeing the greatest increase in males (+ 142.8%), while the Eastern Mediterranean region saw the greatest increase in females (+ 98.4%). The Americas had the smallest increase in ASIR for males (+ 16.4%) and was the only region to observe a fall in ASIR for females (− 6.9%).

Amongst EU 15 + countries, Denmark had the greatest increase in ASIR for both males and females, + 89.3 and 82.8%, respectively. Austria was among the only three countries witnessing a fall in ASIR for males and saw the greatest fall (− 18.0%). Sweden saw the greatest fall in ASIR for females (− 24.0%).

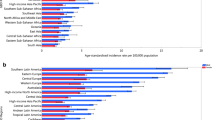

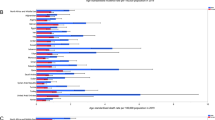

Tables 1 and 2 and, Figs. 1, 2 depict gender-specific trends in KC ASIR across EU 15 + countries and 6 WHO regions.

Age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR) for females (a) and males (b), age-standardized mortality rates for females (ASMR) (c) and males (d), mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIR) for females (e) and males (f), and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for females (g) and males (h) for kidney cancer (KC) for EU 15 + countries in 2019. All indices are per 100,000 population.

Age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR) for males (a) and females (b), age-standardized mortality rates for males (ASMR) (c) and females (d), mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIR) for males (e) and females (f) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for males (g) and females (h) for kidney cancer (KC) for WHO regions in 2019. All indices are per 100,000 population. The figure is created by Dr. Chinmay Jani with mapchart.net (URL: https://www.mapchart.net/) and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Joinpoint analyses for ASIR in males and females are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3

Global ASIR for males increased between 1990 and 1994 (EAPC 2.6 [2.1–3.2]), but from 1994 to 1997, the change was not statistically significant (EAPC: 0.8 [− 1.0 to 2.5]). Between 1997 and 2009, the ASIR increased again (EAPC; 1.6 [1.4–1.7]), and since 2009, the trajectory in ASIR has been mostly flat (EAPC 0.1 [− 0.1 to 0.2]). Amongst EU15 + countries, recent trends have been mostly flat or negative. Most recently, the greatest increase has been observed in the UK between 2006 and 2019 (EAPC: 0.6 [0.5–0.7]). The greatest decrease has been observed in Norway between 2011 and 2019 (EAPC: − 2.1 [− 2.6 to − 1.5]).

The rate of increase in ASIR has been variable amongst the WHO regions. Between 2011 and 2019, the Eastern Mediterranean region observed the greatest increase in ASIR (EAPC: 3.1 [2.9–3.3]). Conversely, the Americas have seen the slowest rate of increase between 2002 and 2019 (EAPC: 0.1 [0.1–0.2]).

Global ASIR for females increased between 1990 and 1993 (EAPC; 1.5 [0.8–2.3)], the rate of growth slowed between 1993 and 2009 (EAPC; 0.7 [0.6–0.7]). Between 2009 and 2014, ASIR decreased (EAPC; − 0.7 [− 1.1 to − 0.2]), while the curve has been flat between 2014 and 2019 (EAPC; 0.0 [− 0.3 to 0.4]). As with males, recent ASIR trends in females have mostly been flat or negative. The observed increase in Australia between 2017 and 2019 (EAPC: 1.1 [− 2.6 to 4.9]) was statistically non-significant. The greatest decrease has been observed in Austria between 1990 and 2019 (EAPC: − 0.9 [− 1 to − 0.9]).

Recent ASIR trends in WHO regions for females have mostly been positive. The Eastern Mediterranean region has seen the greatest increase between 1999 and 2019 (EAPC: 2.6 [2.5–2.6]). The Americas are the only region to see a fall recently, between 2003 and 2019 (EAPC: − 0.5 [− 0.5 to − 0.4]).

Trends in KC ASMR, 1990–2019

Across the entire study period, there was a rise in ASMR globally for males (+ 19.4%) and a fall for females (− 2.3%). ASMR mainly increased across most WHO regions. The Eastern Mediterranean region had the greatest increase across the study period for males and females, + 87.8% and + 43.0%, respectively. The Americas had the smallest increase for males (+ 8.3%) and was the only region to see a decrease in females (− 16.4%). Recently, the Eastern Mediterranean region observed the greatest increase between 2011 and 2019 (EAPC: 2.3 [2.1–2.4]). The Western Pacific is the only region to observe a decrease recently, between 2011 and 2019 (EAPC: − 0.4 [− 0.7 to − 0.2]).

Among EU 15 + countries, Denmark had the greatest increase in ASMR across the study period for males and females, + 41.7% and 37.7%, respectively. Conversely, Austria had the greatest decrease for males and females, − 33.8% and − 35.8% respectively.

Tables 1 and 2 and, Figs. 1, 2 depict gender-specific trends in KC ASMR across EU 15 + countries and 6 WHO regions.

The Joinpoint analyses for ASMR in males and females are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 4

Global ASMR for males increased between 1990 and 1993 (EAPC: 1.9 [1–2.8]). Between 1993 and 2009, the rate of increase slowed (EAPC: 0.9 [0.8–0.9]). Between 2009 and 2019, there has been a non-significant decrease in ASMR (EAPC: − 0.2 [− 0.3 to 0]).

Amongst EU 15 + countries, recent trends have mostly been negative, except in the USA, in which there has been a recent growth in ASMR between 2014 and 2019 (EAPC 0.7 [0.2–1.1]). Recently, Norway has observed the greatest decrease between 2012 and 2019 (EAPC: − 2.2 [− 2.6 to − 1.8]). WHO regions have mostly seen an increase in ASMR recently.

Global, ASMR for females increased between 1990 and 1994 (EAPC: 0.9 [0.5–1.2]). The trend reversed but was statistically non-significant between 1994 and 1997 (EAPC: − 0.4 [− 1.5 to 0.6]). Again, there was an increase in ASMR between 1997 and 2006 (EAPC: 0.3 [0.1–0.4]). The trend between 2006 and 2019 showed an improvement in mortality (EAPC: − 0.6 [− 0.6 to − 0.5]). The South-East Asian region has seen the largest increase between 2012 and 2019 (EAPC: 1.5 [1.2–1.8]). Europe was the only region with negative growth recently, between 2005 and 2019 (EAPC: − 0.2 [− 0.3 to − 0.2]).

Amongst EU 15 + countries, recent trends have been mixed. The greatest increase but statistically non-significant was observed in the USA between 2017 and 2019 (EAPC: 1 [0–2]). The greatest decrease was observed in Denmark between 1998 and 2019 (EAPC: − 1.6 [− 1.7 to − 1.5]). WHO regions have mostly seen an increase in ASMR recently.

Trends in KC disability-adjusted life-years, 1990–2019

Across the 29-year study period, there was a rise in DALYs globally for males (+ 13.1%) and a fall for females (− 9.4%). Similar trends were seen across all six regions as well. The Eastern Mediterranean region saw the greatest increase for males (+ 76.6%), whereas the Americas saw the smallest rise (+ 2.1%). Apart from the Americas (− 23.5%), all regions saw a rise in DALYs for females, led by the Eastern Mediterranean region (+ 36.3%).

In the EU15 + countries, Denmark saw the greatest rise in DALYs for both males and females, + 38.6% and + 30.2 respectively. Austria saw the greatest decrease in DALYs across the study period for males and females, − 39.5% and − 41.2%, respectively. Figures 1 and 2 depict gender-specific trends in KC DALYs across EU 15 + countries and 6 WHO regions.

Tables 1 and 2 and, Figs. 1 and 2 depict gender-specific trends in KC DALY across EU 15 + countries and 6 WHO regions.

The Joinpoint analyses for DALYs in males and females are shown in Table 5 and Fig. 5

Globally, DALYs for males were increasing from 1990 to 1994 (EAPC: 1.8 [1.3–2.2]), followed by a slight decrease from 1994 to 1998 (EAPC: − 0.1 [− 0.9 to 1.4]) and an increase between 1998 to 2005 (EAPC: 1.2 [0.9–1.4]). Since 2005, DALYs have plateaued (EAPC: − 0.2 [− 0.2 to 0.1]).

Amongst EU15 + countries, recent trends have mainly shown reductions, with the greatest decrease amongst males in Ireland from 2009 to 2019 (EAPC: − 1.5 [− 1.8 to 1.1)]. The greatest rise recently was seen in the USA from 2013 to 2019 (EAPC: 0.5 [0.1–0.8]).

Trends have been mixed amongst WHO regions recently. The Eastern Mediterranean region has had the greatest increase recently, between 2000 and 2019 (EAPC; 1.9 [1.9–2.0]). Meanwhile, the Western Pacific region had the greatest decrease recently, between 2011 and 2019 (EAPC; − 0.5 [− 0.8 to − 0.1]). Also, trends across WHO regions have mainly been non-significantly positive recently. The greatest recent rise was seen in South-East Asia between 2012 and 2019 (EAPC: 1.4 [1.1–1.7]). The Americas were the only region with a decrease, albeit not significant (EAPC; − 0.1 [− 0.3 to − 0.1]).

Similar DALYs trends were seen globally for females. Between 1990 and 1994, there was a moderate increase (EAPC: 0.4 [− 0.1 to 0.9)]. Since 1994, there has been a non-significant decrease till 2005. Since 2005, there has been a significant decrease (EAPC: − 0.7 [− 0.7 to − 0.6]). Amongst EU15 + countries, recent trends have been mostly negative for males. The most recent significant increase was observed in Australia between 2016 and 2019 (EAPC: 0.9 [0.3–1.6]). The greatest decrease was observed in Belgium between 1999 and 2019 (EAPC: − 1.3 [− 1.5 to − 1.1]).

Trends in KC MIR, 1990–2019

Across the study period, there was a decrease in MIR globally for both males (− 13.7%) and females (− 13.9%). All EU 15 + countries saw a decrease in MIR across the study period. Portugal saw the greatest decrease in males with a − 29.0% fall, while Ireland saw the greatest decrease in females with a − 26.6% fall. Sweden saw the smallest decrease in males and females with only a − 11.7% and − 8.5% fall, respectively. These trends were reflected across WHO regions, where all regions saw decreases in MIR across the study period. The Western Pacific region saw the greatest decrease in MIR in males with a − 27.3% reduction, while the Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean region were equivalent for females with − 27.9% reductions. The Americas saw the smallest decrease in MIR for both males and females over the study period, − 6.9% and − 10.2%, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to analyze the trends of incidence, mortality, mortality to incidence ratio, and DALYs associated with KC among EU15 + countries and 6 WHO regions, using the GBD study data and Joinpoint regression analysis. During a 29-year interval, while incidence and mortality from KC increased in most of the included countries, a drop in MIR was noted in all countries. Trends in DALYs were variable between countries. High-income countries had the highest values of ASIR, ASMR, and DALYs, concurring with previous studies11,23. This could be partly attributed to a better performing cancer registry system and a higher prevalence of KC-related risk factors23.

We found that the incidence of KC has been increasing in most EU15 + countries, which is congruent with previous reports11,23. The rise in incidence is likely in part due to greater detection of early-stage KC on cross-sectional imaging and partly due to the increasing prevalence of smoking, obesity, and hypertension which are among the strongest risk factors of KC5,6,7,11,24. In terms of smoking, an addition of more than 200 million daily smokers was noted between 1980 and 2012, probably contributing to the development of KC worldwide25,26. However, recent declines in smoking rates have occurred in developed countries due to anti-smoking campaigns. This trend may be reflected by the decline in EAPC seen in the last decade in the high-income and upper-middle-income countries as per World Bank classification23. Similarly, worldwide obesity prevalence had doubled during the past decades, with increasing trends seen especially in developed countries27,28. This increase in obesity prevalence parallels our results showing that developed countries had a notable increase in incidence with the highest elevations noted in the World Bank upper-middle-income category for males. Occupational exposures to toxic compounds such as cadmium have also been found to elevate the risk of KC among males, however, to a lesser extent29. Even though the contribution ratio of occupational exposure to trichloroethylene to kidney cancer incidence and mortality was relatively weak in the GBD database, protection is mandatory in the organic/chlorinated solvent industry23. Recent analysis of risk factor contribution to global cancer burden in 2019 showed that for both sex combined, 33.8% of deaths could be attributed to risk factors analyzed with 19% attributed to High body-mass index, with 33% absolute increase since 2010, 18.1% attributed to smoking, with 19.1% absolute increase since 2010, < 1% attributed to occupational exposure to trichloroethylene, with 40.5% absolute increase since 201030.

Another potential cause of the rising incidence is the higher utilization of imaging and discovery of incidental small renal masses, which account for nearly half of the new cases of renal cell carcinoma31. Detection of lower stage disease is associated with a better prognosis, and therefore the earlier detection of KC, as per the stage migration phenomenon, may be responsible for some of the improvements in patient outcomes32. Asymptomatic masses are more frequently diagnosed given the increased clinical use of modern imaging such as abdominal CT scans for evaluating urological and non-urological symptoms11,33. Indeed, a study in Canada showed an annual increase of CT imaging rates by 11.6% between 2000 and 2006, which decreased to 3.7% from 2013 to 201634. This is comparable to our results where Canada had an EAPC of ASIR of 4.4 for females in the years 1998–2009 and 5.9 for males in the years 2001–2004, compared to a lesser value of -1.6 in the years 2006–2016 for females and -0.1 for the years 2008–2019 in males. Similarly, CT use continuously increased for assessing abdominal pain in the emergency departments of the United States from 1997 to 2016, concurring with an increased ASIR for males in the USA35. The increased frequency of radiological diagnosis would not be the sole reason behind the rise in ASIR in low-income countries since it has been demonstrated that these countries do not have equal access to imaging modalities compared to high-income countries36. An improvement in healthcare access is noted in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region in the past few decades with a rise in life expectancy at birth from 65 years in 1990 to 71 years in 2012, which could reflect on the increased diagnosis of KC37. However, significant disparities among and within countries still exist, especially with the unregulated intervention of the private sector to fill the gaps of the governments’ insufficient coverage, raising concern for equity37. Thus, a multifactorial model would be the ultimate explanation for the increased KC incidence in different countries.

Lower MIRs worldwide may be partly due to the stage migration with the detection of lower stage disease on cross-sectional imaging. These tumors are associated with a lower likelihood of cancer mortality, and 30% were indolent on post-operative pathology38,39. However, a recent article highlighted a paucity of imaging modalities in low to middle-income countries. Thus, over-diagnosis is not the only explanation for the universal drop in MIR36. We showed that mortality is also decreasing in most of the included countries. One plausible explanation for the mortality drop would be the approval of 10 novel drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of metastatic RCC between 2005 and 2016, with the first approved targeted therapy being Sorafenib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)40,41. The inclusion of targeted therapies in the therapeutic arsenal of KC was proven by several studies to positively impact patients’ survival42,43,44. Our results mirror these findings as we noticed a drop in EAPCs of ASMRs from 2005 onwards, during the era of targeted therapies, in the high-income and upper-middle-income classes in the World Bank classification. On the other hand, EAPCs of ASMRs were still increasing after 2005 in middle-low to low-income countries, possibly due to a lack of access to comprehensive multidisciplinary team care, clinical trials, and advanced treatment modalities such as stereotactic radiotherapy medicine45. Additionally, now a subset of patients with metastatic RCC can be cured with immune-oncology (IO-IO) combinations but these recently entered into practice in 201846. Therefore, future analysis will give information about its effects on survival and mortality. Poor access to treatment and imaging modalities plays a role in increased mortality rates in such regions since tumors are diagnosed at a later stage and are treated in a suboptimal manner45. Indeed, we highlighted that middle and low-income countries had higher increases in ASMRs and smaller drops in MIR than high-income countries. Similarly, a previous article had comparable conclusions to ours, having found a positive correlation between the availability of imaging examinations/effective systemic therapies in high-income countries and a favorable prognosis; the authors also concluded that MIRs were negatively correlated with the human development index and the current health expenditure per capita47. In this setting, Fay et al. emphasized the importance of clinical trial enrollment as a solution to health disparities by concluding to a similar overall survival among patients with metastatic RCC recruited in clinical trials across different geographic regions, despite different baseline characteristics48. We observed that the DALYs were decreasing in most of included Western European countries, especially in females. However, the DALYs remained stable in the European region. This is probably attributed to an increase in DALYs in Eastern Europe as opposed to a decrease in Western Europe49.

Finally, as we demonstrated an increase in incidence and mortality from KC in most included countries and regions, future focus is needed to implement strategies for the detection of early-stage KC. Extra efforts need to be put into decreasing the prevalence of smoking, obesity, and hypertension, which are among the strongest risk factors of KC, through campaigns and medical attention50,51. Although MIRs are decreasing, thus indicating an improvement in outcomes, equal access to treatment would ameliorate even more the situation worldwide, especially by using novel targeted and IO therapies51.

Limitations

Limitations following the use of the GBD database were noted previously by our group and the GBD Study collaborators15,16,52. Regarding this study, the first limitation is the presence of alterations in data coding systems and country-specific practice during the study period, markedly a shift from the use of ICD 9 to ICD 10. However, the GBD authors map mortalities to causes of death lists, adjusting by such to the different coding systems. Secondly, variability in the reliability of death certification exists both within and across countries, with worldwide errors in death certification ranging from 39 to 61%53,54,55. Also, only 39% of deaths globally were registered in 2012. Considering that Europe, the Americas, and Australasia were ranked among the best continents with civil registration and vital statistics56, we demonstrated valid data of the EU15 + countries and 6 WHO regions assessed. To balance the under-registration, the GBD uses garbage-code distribution algorithms and corrections17,18, which relate to deaths resulting from poorly defined diagnoses or those that cannot be the single underlying cause of death. Thirdly, we could not extract the subcategorized data by individual KC histological subtypes from the GBD Study results tool, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Indeed, histopathological subtypes and stages of KC amend to different clinical significance and urgent management. Finally, since our study is an observational analysis of the trends in the burden of KC across 29 years in EU15 + countries and 6 WHO regions, causal inferences cannot be concluded. Moreover, as seen in observational analyses, some potential confounders were not accounted for by using sex-specific, age-standardized incidence and mortality rates.

Conclusions

While the incidence and mortality from KC rose in most EU15 + countries and WHO regions from 1990 to 2019, the universal drop in MIR suggests an overall improvement in KC outcomes. This is likely multifactorial, including earlier detection of KC and improved treatments. These results are also of interest from a public health perspective as they highlight the importance of adjustable risk factor modification. A further study among lower-income countries would help identify the burden of disease across these regions and subsequently enable appropriate strategies to be developed to bridge disparities across countries and optimize patient care.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the GBD repository, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Abbreviations

- ASIR:

-

Age-standardized incidence rate

- ASMR:

-

Age-standardized mortality rate

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- EAPC:

-

Estimated annual percentage change

- EU:

-

European Union

- GBD:

-

Global burden of disease

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- IO:

-

Immuno-oncology

- KC:

-

Kidney cancer

- RCC:

-

Renal cell carcinoma

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Cai, Q. et al. Temporal trends of kidney cancer incidence and mortality from 1990 to 2016 and projections to 2030. Transl. Androl. Urol. 9(2), 166–181 (2020).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–249 (2021).

Rini, B. I., Campbell, S. C. & Escudier, B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 373(9669), 1119–1132 (2009).

Moch, H., Cubilla, A. L., Humphrey, P. A., Reuter, V. E. & Ulbright, T. M. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part A: Renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur. Urol. 70(1), 93–105 (2016).

Capitanio, U. et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 75(1), 74–84 (2019).

Gild, P., Ehdaie, B. & Kluth, L. A. Effect of obesity on bladder cancer and renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival. Curr. Opin. Urol. 27(5), 409–414 (2017).

Lotan, Y. et al. Renal-cell carcinoma risk estimates based on participants in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial and national lung screening trial. Urol. Oncol. 34(4), 167e9-216 (2016).

Hidayat, K., Du, X., Zou, S. Y. & Shi, B. M. Blood pressure and kidney cancer risk: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Hypertens. 35(7), 1333–1344 (2017).

Lowrance, W. T., Ordonez, J., Udaltsova, N., Russo, P. & Go, A. S. CKD and the risk of incident cancer. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25(10), 2327–2334 (2014).

Kidney cancer fact sheet. International Agency for Cancer Research. WHO. http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed Dec. 2020. (https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/29-Kidney-fact-sheet.pdf). (Accessed on April 26 2022).

Znaor, A., Lortet-Tieulent, J., Laversanne, M., Jemal, A. & Bray, F. International variations and trends in renal cell carcinoma incidence and mortality. Eur. Urol. 67(3), 519–530 (2015).

Ljungberg, B. et al. European association of urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: The 2019 Update. Eur. Urol. 75(5), 799–810 (2019).

Chow, W. H. & Devesa, S. S. Contemporary epidemiology of renal cell cancer. Cancer J. 14(5), 288–301 (2008).

Levi, F. et al. The changing pattern of kidney cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. BJU Int. 101(8), 949–958 (2008).

Salciccioli, J. D. et al. Respiratory disease mortality in the United Kingdom compared with EU15+ countries in 1985–2015: Observational study. BMJ 363, k4680 (2018).

Goodall R, Salciccioli JD, Davies AH, Marshall D, Shalhoub J. Trends in peripheral arterial disease incidence and mortality in EU15+ countries 1990–2017. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020:2047487319899626.

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–88.

Al-Balah, A., Goodall, R., Salciccioli, J. D., Marshall, D. C. & Shalhoub, J. Mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm: Trends in European Union 15+ countries from 1990 to 2017. Br. J. Surg. 107(11), 1459–1467 (2020).

Hughes, W. et al. Editor’s choice—trends in lower extremity amputation incidence in European Union 15+ countries 1990–2017. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 60(4), 602–612 (2020).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136(5), E359–E386 (2015).

Kim, H. J., Fay, M. P., Feuer, E. J. & Midthune, D. N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 19(3), 335–351 (2000).

Bai, X., Yi, M., Dong, B., Zheng, X. & Wu, K. The global, regional, and national burden of kidney cancer and attributable risk factor analysis from 1990 to 2017. Exp Hematol Oncol. 9, 27 (2020).

Zucchetto, A. et al. History of treated hypertension and diabetes mellitus and risk of renal cell cancer. Ann. Oncol. 18(3), 596–600 (2007).

Hu, J., Mao, Y. & White, K. Renal cell carcinoma and occupational exposure to chemicals in Canada. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 52(3), 157–164 (2002).

Ng, M. et al. Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980–2012. JAMA 311(2), 183–192 (2014).

Finucane, M. M. et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 377(9765), 557–567 (2011).

Malik, V. S., Willet, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Nearly a decade on—trends, risk factors and policy implications in global obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16(11), 615–616 (2020).

Hu, J., Mao, Y., White, K., Group TCCRER. Renal cell carcinoma and occupational exposure to chemicals in Canada. Occup. Med. 52(3), 157–164 (2002).

GBDCRF Collaborators. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010–19: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 400(10352), 563–591 (2022).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66(1), 7–30 (2016).

Kane, C. J., Mallin, K., Ritchey, J., Cooperberg, M. R. & Carroll, P. R. Renal cell cancer stage migration: Analysis of the national cancer data base. Cancer 113(1), 78–83 (2008).

Sun, M. et al. Age-adjusted incidence, mortality, and survival rates of stage-specific renal cell carcinoma in North America: A trend analysis. Eur. Urol. 59(1), 135–141 (2011).

Smith-Bindman, R. et al. Trends in use of medical imaging in US health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000–2016. JAMA 322(9), 843–856 (2019).

Wang, R. C. et al. Trends in use of diagnostic imaging for abdominal pain in U.S. emergency departments. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 216(1), 200–208 (2021).

Hricak, H. et al. Medical imaging and nuclear medicine: A lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol. 22(4), e136–e172 (2021).

Mate, K., Bryan, C., Deen, N. & McCall, J. Review of health systems of the Middle East and North Africa Region. In International Encyclopedia of Public Health (eds Mate, K. et al.) 347–56 (Elsevier, 2017).

Vaishampayan, U. et al. The effect of targeted therapy on overall survival in advanced renal cancer: A study of the national surveillance epidemiology and end results registry database. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 12(2), 124–129 (2014).

Rao, A., Wiggins, C. & Lauer, R. C. Survival outcomes for advanced kidney cancer patients in the era of targeted therapies. Ann. Transl. Med. 6(9), 165 (2018).

Vachhani, P. & George, S. VEGF inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 14(12), 1016–1028 (2016).

Mihaly, Z., Sztupinszki, Z., Surowiak, P. & Gyorffy, B. A comprehensive overview of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 12(7), 857–872 (2012).

Shek, D. et al. Epidemiologic trends in renal cell carcinoma in the cytokine and post-cytokine eras: A registry analysis of 28,252 patients. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 10(2), 93–98 (2012).

Kim, J. H. et al. Association of prevalence of benign pathologic findings after partial nephrectomy with preoperative imaging patterns in the United States from 2007 to 2014. JAMA Surg. 154(3), 225–231 (2019).

Shannon, B. A., Cohen, R. J., de Bruto, H. & Davies, R. J. The value of preoperative needle core biopsy for diagnosing benign lesions among small, incidentally detected renal masses. J. Urol. 180(4), 1257–1261 (2008).

Lopes Gde L, Jr., de Souza JA, Barrios C. Access to cancer medications in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(6):314-22.

Elaidi, R. et al. Comparative efficacy of first-line immune-based combination therapies in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 12(6), 1673 (2020).

Sung, W. W., Ko, P. Y., Chen, W. J., Wang, S. C. & Chen, S. L. Trends in the kidney cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios according to health care expenditures of 56 countries. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1479 (2021).

Fay, A. P., McKay, R. R., Lin, X., Simantov, R. & Choueiri, T. K. Impact of geographic regions on overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from an international clinical trials database. J. Glob. Oncol. 4, 1–14 (2018).

Safiri, S. et al. The burden of kidney cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 13862 (2020).

Tahbaz, R., Schmid, M. & Merseburger, A. S. Prevention of kidney cancer incidence and recurrence: Lifestyle, medication and nutrition. Curr. Opin. Urol. 28(1), 62–79 (2018).

Sims, J. N. et al. Racial disparities and preventive measures to renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15(6), 1089 (2018).

GBD datasets. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/about-ghdx/ghdx-records-explained. (Accessed on April 26 2022).

Burger, E. H., van der Merwe, L. & Volmink, J. Errors in the completion of the death notification form. S. Afr. Med. J. 97(11), 1077–1081 (2007).

Katsakiori, P. F., Panagiotopoulou, E. C., Sakellaropoulos, G. C., Papazafiropoulou, A. & Kardara, M. Errors in death certificates in a rural area of Greece. Rural Remote Health 7(4), 822 (2007).

Lu, T. H. et al. Factors associated with errors in death certificate completion. A national study in Taiwan. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 54(3), 232–238 (2001).

Mikkelsen, L. et al. A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: Monitoring data quality and progress. Lancet 386(10001), 1395–1406 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each of the authors significantly contributed to this manuscript. Drs. C.J., N.A., C.M., R.R.M. and D.C.M. made significant contributions to the concept and design of this study. Drs. J.S., C.J. and D.C.M. were significantly involved in the statistical analysis. Drs. C.J., N.A., C.M., P.B., G.H., H.S., J.S., R.R.M. and D.C.M., Miss R.J. and, Mr R.S. were greatly involved in drafting manuscript. Drs. C.J., N.A., R.R.M. and D.C.M. were involved in critical revision of the manuscript and contributed vital intellectual content. All authors have reviewed the manuscript. Dr. C.J. (corresponding author, guarantor) takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jani, C., Abdallah, N., Mouchati, C. et al. Trends of kidney cancer burden from 1990 to 2019 in European Union 15 + countries and World Health Organization regions. Sci Rep 12, 22368 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25485-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25485-8

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Kidney cancer in the Middle East and North Africa region: a 30-year analysis (1990–2019)

Scientific Reports (2024)