Abstract

Seroma or lymphocele remains the most common complication after mastectomy and lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Many different techniques are available to prevent this complication: wound drainage, reduction of the dead space by flap fixation, use of various types of energy, external compression dressings, shoulder immobilization or physical activity, as well as numerous drugs and glues. We searched MEDLINE, clinicaltrials.gov, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases for publications addressing the issue of prevention of lymphocele or seroma after mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy. Quality was assessed using Hawker’s quality assessment tool. Incidence of seroma or lymphocele were collected. Fifteen randomized controlled trials including a total of 1766 patients undergoing radical mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy for breast cancer were retrieved. The incidence of lymphocele or seroma in the study population was 24.2% (411/1698): 25.2% (232/920) in the test groups and 23.0% (179/778) in the control groups. Neither modification of surgical technique (RR 0.86; 95% CI [0.72, 1.03]) nor application of a medical treatment (RR 0.96; 95% CI [0.72, 1.29]) was effective in preventing lymphocele. On the contrary, decreasing the drainage time increased the risk of lymphocele (RR 1.88; 95% CI [1.43, 2.48). There was no publication bias but the studies were of medium to low quality. To conclude, despite the heterogeneity of study designs, drainage appears to be the most effective technique, although the overall quality of the data is low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) and mastectomy are performed as part of the surgical management of breast cancer and are associated with significant morbidity, as 70% of patients experience complications1,2.

Seromas or lymphoceles are the most common complication of these procedures and can delay local healing and initiation of adjuvant therapy. They are also a source of discomfort for patients. Many techniques have been developed to decrease the risk of seroma formation: wound drainage3, reduction of the dead space by flap fixation4, use of various types of energy5, external compression dressings 6, shoulder immobilization or physical activity7, as well as numerous drugs and glues8,9,10,11.

Two previous Cochrane meta-analyses have evaluated fibrin glues and wound drainage and concluded on the inefficacy of fibrin glues and moderate efficiency of drainage supported by low quality studies3,8. To our knowledge, no meta-analysis has compared all proposed techniques for seroma prevention after mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy.

Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and the Cochrane Collaboration recommendations12. The “Prevention of seroma after breast cancer surgery” trial was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RFVG6.

Literature search

We searched MEDLINE, clinicaltrials.gov, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases for publications of randomized controlled trials (RCT) and clinical trials addressing the issue of prevention of lymphocele or seroma after mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy. Various combinations of the following terms were searched: “lymphocele”, “lymphorrhea”, “seroma”, “breast cancer”, “breast surgery”.

Eligibility criteria

Three authors independently conducted the initial research to evaluate eligibility criteria (AC, MLB, KM). We selected randomized controlled trials and clinical trials published after January 2000 in English, including more than 50 participants, reporting the incidence of lymphocele or seroma after mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. The latest search was performed in March 2021.

The following publications were excluded: retrospective studies, case reports, letters to the editor, publications concerning plastic surgery, brachytherapy or radiation therapy.

Data collection process and outcome measures

Three authors independently performed data collection using a standardized data extraction table (AC, MLB, KM). The following data were extracted: author, year and country of publication, study characteristics, prevention technique, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of patients, data necessary to build 2 × 2 contingency tables.

Statistical analysis

Publication bias

A funnel plot was used to visualize publication bias. The estimate of the difference between groups was pooled, depending upon the effect weights of the variance estimate determined in each trial. Egger’s test was used to assed asymmetry of the funnel plot13.

Outcomes

For dichotomous outcomes, the Mantel–Haenszel method was used for calculation of relative risk (RR) under the fixed-effect and random-effects models13. The Forest plot was used for graphic display of the results of the meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of studies was calculated using the I2 index. The I2 value was interpreted by balancing the direction and magnitude of I2 with its statistical significance, using the values in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as a guide14: 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: represents considerable heterogeneity. Meta‐analyses with insignificant heterogeneity were calculated using the fixed‐effects model15. For meta-analyses with low or moderate heterogeneity, the random‐effects model was used16. The square around the estimate represents the accuracy of the estimation (sample size) and the horizontal line represents the 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Data were entered in an Excel file and all statistical analyses were performed using Rstudio software (RStudio, PBC, Boston, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Quality assessment of the studies included

We used a quality assessment tool elaborated by Hawker et al.17 in 2002 for systematic review of qualitative evidence. The scale contains nine items assessing abstract/title, introduction/aims, method/data, sampling, data analysis, ethics/bias, results, transferability and implications. Each item is rated as “good”, “fair”, “poor” and “very poor”. Lorenc et al.18 added a graduation to this scale by assigning answers from 1 point (very poor) to 4 points (good), to provide a final score for each study (9 to 36 points). The overall quality grades were defined by the following description: grade A (high quality) 30–36 points; grade B (medium quality), 24–29 points and grade C (low quality), 9–24 points. Each of the three readers assessed the studies independently. When differences were observed, a majority agreement was reached.

Results

Study selection

The PRISMA flow diagram explaining the literature search strategy and trial selection is presented in Fig. 1. Fifteen randomized controlled trials including a total of 1766 patients undergoing mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy for breast cancer were retrieved from the electronic databases. Analysis was based on 920 patients in the test groups and 878 patients in control groups. The characteristics of the trials included in this meta-analysis are provided in Table 1. The technique used in each article is described in Table 1. The incidence of lymphocele or seroma in the study population was 24.9% (411/1648): 29.5% (271/920) in the test groups and 23.9% (210/878) in the control groups.

As the study by Dalberg et al.22 compared two different techniques in two separate groups of patients, we decided to divide this study into one group treated by drainage and the other group treated by the fascia preservation surgical technique.

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are described in Table 1. Two of the 15 studies concerned lymphoceles20,31, while all of the other studies concerned seromas. Six studies did not specify their definition of seroma, 9 studies reported a clinical definition of seroma or lymphocele (palpation, clinical examination, needle aspiration) and one study used an ultrasound definition. Five studies reported statistically significant results19,20,22,25,32,23,.

Publication bias

The funnel plot did not show any asymmetry (Supplemental Fig. 1). Egger’s test did not reveal any publication bias (p = 0.36).

Prevention of seroma regardless of the technique

Significant heterogeneity was observed between the 15 studies (I2 = 73%, p < 0.01). Therefore, in the random effects model, none of the techniques allowed statistically significant prevention of lymphocele or seroma formation (RR 1.23; 95% CI [0.92, 1.65]; Fig. 2).

Prevention of seroma according to the various techniques

Medical treatment

Significant heterogeneity was observed between the 6 studies (I2 = 68%, p < 0.01)19,26,30,31,32. Therefore, in the random effects model, medical treatments did not allow statistically significant prevention of lymphocele or seroma (RR 0.96; 95% CI [0.72, 1.29]; Fig. 3).

Surgical techniques

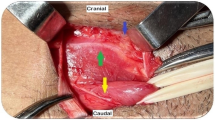

Four studies evaluated surgical techniques for the prevention of lymphocele or seroma. Dalberg et al.22 with pectoral fascia preservation, Gong et al.25 with lymphatic vessel ligation and padding, Ribeiro27 and Khan S et al.28 with the use of a harmonic scalpel. Significant heterogeneity was observed between the 4 studies (I2 = 77%, p < 0.01)22,25,27,28. Therefore, in the random effects model, no specific surgical technique allowed statistically significant prevention of lymphocele or seroma (RR 0.86; 95% CI [0.72, 1.03]; Fig. 4).

Modification of the drainage process

No heterogeneity was observed between the 4 studies (I2 = 0%, p = 0.83)20,22,23,24. Therefore, in the fixed effects model, the risk of lymphocele or seroma was significantly increased by modification of the drainage technique (RR 1.88; 95% CI [1.43, 2.48]; Fig. 5).

Other techniques

One study that investigated prevention of lymphocele or seroma using fibrin glue21 found this technique to be statistically ineffective (RR 1.36; 95% CI [0.77; 2.38]).

One study that investigated prevention of lymphocele or seroma using physical activity and manual lymphatic drainage29 found these technique to be statistically ineffective (RR 1.67; 95% CI [0.44; 6.29]).

Study quality

The results of the quality assessment are described in Supplemental Table 1. One study was considered to present high quality (Grade A), 8 studies were considered to present medium quality (Grade B), and 6 studies were considered to present low quality (Grade C).

Discussion

This work represents the first meta-analysis of all techniques proposed for the prevention of lymphocele formation after mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy in prospective randomized controlled trials and clinical trials. Global analysis of all of the various techniques showed that they were not effective to prevent lymphocele formation (RR 1.23; 95% CI [0.92, 1.65]). Analysis of studies based on modification of the drainage technique showed a negative effect on seroma prevention (RR 1.88; 95% CI [1.43, 2.48]). Glues and drugs were not effective (RR 1.36; 95% CI [0.77; 2.38], RR 0.96; 95% CI [0.72, 1.29]). The overall quality of these items was moderate with 8 items presenting average quality, 6 items presenting low quality, and only one item presenting high quality.

In this study, we chose to restrict our analysis to the population at high risk of lymphocele or seroma34. In our meta-analysis, regardless of the definitions and techniques used to prevent seroma or lymphocele, the overall incidence of these complications was 24.2% (411/1698): 25.2% (232/920) in the test groups and 23.0% (179/778) in the control groups. The reported seroma or lymphocele incidence is dependent on the author’s definition of seroma or lymphocele and the method of detection used. Risk factors for seroma formation include age, body mass index (BMI), tumor size, use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, type of surgery (MRM versus breast-conserving surgery)34, axillary lymph node status, axillary lymph nodes sampled or removed, and subsequently the extent of surgical dead space produced35. In our meta-analysis, only one article21 considered neoadjuvant chemotherapy to be an exclusion criterion, while most of other studies did not mention neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Other risk factors, except for the type of surgery, were not well documented. This lack of information on risk factors may result in an incidence bias.

The various techniques tested to reduce seroma or lymphocele after breast surgery are based on the different physiological theories. Six studies tested a drug for prevention of seromas. These drugs inhibit the inflammatory or immunopathological response, which is considered to play a role in seroma formation35. Four studies evaluated a specific surgical procedure. A French multicenter, superiority, randomized controlled trial, compared seroma formation using quilting suture versus conventional closure with drainage in 320 patients undergoing mastectomy36, results have not yet been published. A meta-analysis by Sajid et al. studied application of fibrin glue under skin flaps to prevent seroma-related morbidity following breast and axillary surgery8, but this technique failed to reduce the incidence of postoperative seroma (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.90–1.16, p value = 0.73).

Four studies included in our meta-analysis evaluated modification of the drainage technique. Since 1947 and the first description of drainage after axillary dissection for breast cancer by Murphey37, drainage is the technique most commonly used to prevent lymphocele or seroma after radical mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy. In 2013, a Cochrane meta-analysis by Thomson et al.3 compared wound drainage versus no wound drainage after axillary lymphadenectomy for breast carcinoma. Seven RCTs including 960 participants were identified. The quality of trials was generally low, with several studies at risk of selection bias, and no studies used blinding during treatment or outcome assessment. There was a high level of statistical variation between studies, which therefore reduces the reliability of the evidence. The R for seroma formation was 0.46 ([95% CI 0.23–0.91], p = 0.03) in favor of a reduced incidence of seroma in participants with drains inserted.

Finally, wound drainage appears to be the most effective way to prevent seroma, although no consensus has been reached concerning the optimal duration of drainage. However, persistence of foreign devices under the skin could predispose to surgical site infection. Surgical site infection is one of the possible complications after breast cancer surgery, causing significant morbidity, additional costs and which can delay initiation of adjuvant therapy. In Reiffel’s review38 of the potential association between closed-suction drains and surgical site infection, few studies suggested an increased risk of surgical site infection associated with drain placement and no studies attributed a decreased incidence of surgical site infection (including organ/space surgical site infection) with drain placement.

Conclusions

The lack of consensus concerning the definition of lymphocele or seroma is probably responsible for the heterogeneity of seroma incidence reported in the literature and the inefficacy of the techniques proposed for seroma prevention after breast cancer surgery. However, drainage is the most effective technique currently available. Yet, most studies included in the meta-analysis were evaluated to be of medium or low quality.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALND:

-

Axillary lymph node dissection

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MRM:

-

Modified radical mastectomy

- OSF:

-

Open science framework

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

- RR:

-

Relative risk

References

Roses, D. F., Brooks, A. D., Harris, M. N., Shapiro, R. L. & Mitnick, J. Complications of level I and II axillary dissection in the treatment of carcinoma of the breast. Ann. Surg. 230(2), 194 (1999).

Lucci, A. et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J. Clin. Oncol. 25(24), 3657–3663 (2007).

Thomson, D. R., Sadideen, H. & Furniss, D. Wound drainage after axillary dissection for carcinoma of the breast. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, 006823 (2013).

Granzier, R. W. Y. et al. Reducing seroma formation and its sequelae after mastectomy by closure of the dead space: The interim analysis of a multi-center, double-blind randomized controlled trial (SAM trial). Breast 46, 81–86 (2019).

Lumachi, F., Basso, S. M. M., Santeufemia, D. A., Bonamini, M. & Chiara, G. B. Ultrasonic dissection system technology in breast cancer: A case-control study in a large cohort of patients requiring axillary dissection. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 142(2), 399–404 (2013).

O’Hea, B. J., Ho, M. N. & Petrek, J. A. External compression dressing versus standard dressing after axillary lymphadenectomy. Am. J. Surg. 177(6), 450–453 (1999).

Chen, S. C. & Chen, M. F. Timing of shoulder exercise after modified radical mastectomy: A prospective study. Chang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 22(1), 37–43 (1999).

Sajid, M. S., Hutson, K. H., Rapisarda, I. F. & Bonomi, R. Fibrin glue instillation under skin flaps to prevent seroma-related morbidity following breast and axillary surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5, 009557 (2013).

Suarez-Kelly, L. P. et al. Effect of topical microporous polysaccharide hemospheres on the duration and amount of fluid drainage following mastectomy: A prospective randomized clinical trial. BMC Cancer 19(1), 99 (2019).

Gauthier, T. et al. Lanreotide Autogel 90 mg and lymphorrhea prevention after axillary node dissection in breast cancer: A phase III double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 38(10), 902–909 (2012).

Benevento, R. et al. The effects of low-thrombin fibrin sealant on wound serous drainage, seroma formation and length of postoperative stay in patients undergoing axillary node dissection for breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Surg. 12(11), 1210–1215 (2014).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7), e1000097 (2009).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315(7109), 629–634 (1997).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343, d5928 (2011).

Demets, D. L. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Stat. Med. 6(3), 341–350 (1987).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 7(3), 177–188 (1986).

Hawker, S., Payne, S., Kerr, C., Hardey, M. & Powell, J. Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual. Health Res. 12(9), 1284–1299 (2002).

Lorenc, T. et al. Crime, fear of crime and mental health: Synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Public Health Res. 2(2), 1–398 (2014).

Rice, D. C. et al. Intraoperative topical tetracycline sclerotherapy following mastectomy: A prospective, randomized trial. J. Surg. Oncol. 73(4), 224–227 (2000).

Gupta, R., Pate, K., Varshney, S., Goddard, J. & Royle, G. T. A comparison of 5-day and 8-day drainage following mastectomy and axillary clearance. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 27(1), 26–30 (2001).

Ulusoy, A. N., Polat, C., Alvur, M., Kandemir, B. & Bulut, F. Effect of fibrin glue on lymphatic drainage and on drain removal time after modified radical mastectomy: A prospective randomized study. Breast J. 9(5), 393–396 (2003).

Dalberg, K. et al. A randomised study of axillary drainage and pectoral fascia preservation after mastectomy for breast cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 30(6), 602–609 (2004).

Chintamani, A., Singhal, V., Singh, J., Bansal, A. & Saxena, S. Half versus full vacuum suction drainage after modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer: A prospective randomized clinical trial [ISRCTN24484328]. BMC Cancer 5, 11 (2005).

Clegg-Lamptey, J. N. A., Dakubo, J. C. B. & Hodasi, W. M. Comparison of four-day and ten-day post-mastectomy passive drainage in Accra, Ghana. East Afr. Med. J. 84(12), 561–565 (2007).

Gong, Y. et al. Prevention of seroma formation after mastectomy and axillary dissection by lymph vessel ligation and dead space closure: A randomized trial. Am. J. Surg. 200(3), 352–356 (2010).

Cabaluna, N. D. et al. A randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial of the routine use of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in modified radical mastectomy. World J. Surg. 37(1), 59–66 (2013).

Ribeiro, G. H. F. P. et al. Modified radical mastectomy: A pilot clinical trial comparing the use of conventional electric scalpel and harmonic scalpel. Int. J. Surg. 11(6), 496–500 (2013).

Khan, S., Khan, S., Chawla, T. & Murtaza, G. Harmonic scalpel versus electrocautery dissection in modified radical mastectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 21(3), 808–814 (2014).

de Oliveira, M. M. F. et al. Manual lymphatic drainage versus exercise in the early postoperative period for breast cancer. Physiother. Theory Pract. 30(6), 384–389 (2014).

Garza-Gangemi, A. M. et al. Randomized phase II study of talc versus iodopovidone for the prevention of seroma formation following modified radical mastectomy. Rev. Investig. Clin. Organo Hosp. Enfermedades Nutr. 67(6), 357–365 (2015).

Chéreau, E. et al. Evaluation of the effects of pasireotide LAR administration on lymphocele prevention after axillary node dissection for breast cancer: Results of a randomized non-comparative phase 2 study. PLoS ONE 11(6), e0156096 (2016).

Kong, D. et al. OK-432 (sapylin) reduces seroma formation after axillary lymphadenectomy in breast cancer. J. Investig. Surg. 30(1), 1–5 (2017).

Khan, M. A. Effect of preoperative intravenous steroids on seroma formation after modified radical mastectomy. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 29(2), 207–210 (2017).

Kuroi, K. et al. Evidence-based risk factors for seroma formation in breast surgery. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 36(4), 197–206 (2006).

McCaul, J. A. et al. Aetiology of seroma formation in patients undergoing surgery for breast cancer. Breast 9(3), 144–148 (2000).

Ouldamer, L. et al. Dead space closure with quilting suture versus conventional closure with drainage for the prevention of seroma after mastectomy for breast cancer (QUISERMAS): Protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 6(4), e009903 (2016).

Murphey, D. R. The use of atmospheric pressure in obliterating axillary dead space following radical mastectomy. South Surg. 13(6), 372–375 (1947).

Reiffel, A. J., Barie, P. S. & Spector, J. A. A multi-disciplinary review of the potential association between closed-suction drains and surgical site infection. Surg. Infect. 14(3), 244–269 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A.: Design of the work. C.A., M.K., B.M.-L.: drafting. M.K.: analysis. C.A.: data acquisition. R.A., B.C.: reviewing process. R.R.: project supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adrien, C., Katia, M., Marie-Lucile, B. et al. Prevention of lymphocele or seroma after mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy for breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 12, 10016 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13831-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13831-9

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Comparison of the effect of ultrasounic-harmonic scalpel and electrocautery in the treatment of axillary lymph nodes during radical surgery for breast cancer

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2024)

-

Efficacy and safety of surgical energy devices for axillary node dissection: a systematic review and network meta-analysis

Breast Cancer (2023)