Abstract

Awake surgery for low-grade gliomas is currently considered the best procedure to improve the extent of resection and guarantee a "worth living life" for patients, meaning avoiding not only motor but also cognitive deficits. However, tumors located in the right hemisphere, especially in the right frontal lobe, are still rarely operated on in awake condition; one of the reasons possibly being that there is little information in the literature describing the rates and nature of long-lasting neuropsychological deficits following resection of right frontal glioma. To investigate long-term cognitive deficits after awake surgery in right frontal IDH-mutated glioma. We retrospectively analyzed a consecutive series of awake surgical resections between 2012 and 2020 for right frontal IDH-mutated glioma. We studied the patients' subjective complaints and objective neuropsychological evaluations, both before and after surgery. Our results were then put in perspective with the literature. Twenty surgical cases (including 5 cases of redo surgery) in eighteen patients (medium age: 42.5 [range 26–58]) were included in the study. The median preoperative volume was 37 cc; WHO grading was II, III and IV in 70%, 20%, and 10% of cases, respectively. Preoperatively, few patients had related subjective cognitive or behavioral impairment, while evaluations revealed mild deficits in 45% of cases, most often concerning executive functions, attention, working memory and speed processing. Immediate postoperative evaluations showed severe deficits of executive functions in 75% of cases but also attentional deficits (65%), spatial neglect (60%) and behavioral disturbances (apathy, aprosodia/amimia, emotional sensitivity, anosognosia). Four months after surgery, although psychometric z-scores were unchanged at the group level, individual evaluations showed a slight decrease of performance in 9/20 cases for at least one of the following domains: executive functions, speed processing, attention, semantic cognition, social cognition. Our results are generally consistent with those of the literature, confirming that the right frontal lobe is a highly eloquent area and suggesting the importance of operating these patients in awake conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, numerous studies have provided cumulative evidence that the extent of resection is a strong predictor of prolonged survival in (IDH-mutated) diffuse low-grade glioma (DLGG) patients1,2,3,4. Importantly, the effect of surgery has been observed regardless of the IDH-mutated subtypes—1p19q-codeleted oligodendroglioma or 1p19q noncodeleted astrocytoma5,6,7. Accordingly, surgical resection of DLGG is now considered as the first option in the guidelines. However, most patients seek not only for a longer life but also for a life that is worth living (according to their own definition). This problem has been conceptualized as the oncofunctional balance8,9,10,11, and subspecialized neurosurgeons must face the challenge of optimizing this oncofunctional balance. Whereas noninvasive preoperative functional imaging tools (functional and structural MRI, magnetoencephalography, transcranial magnetic stimulation) are helpful in the first approach of individualized functional mapping (especially in regard to determining language lateralization12), the best methodology for functional preservation is to awake the patient and perform continuous intraoperative mapping of cognitive tasks through the use of direct electrical stimulation (DES)13. The efficiency of this method has been demonstrated for motor and speech functions14. Despite the awareness that functions hosted by the right hemisphere are as important as those hosted by the left hemisphere15,16,17, there are only a few teams opting for awake surgery in right-sided tumors, especially for tumors located in the frontal lobes. One possible explanation would be that there is no study in the literature providing a comprehensive overview of the long-lasting neuropsychological deficits that can be observed after resection of glioma located in the right frontal lobe. Indeed, previous reports in this field were often focused on a single task/function and were somehow neuroscience-oriented18,19,20. As proposed recently, the introduction of a new intraoperative task in awake surgery should be grounded on studies demonstrating that patients operated on without this monitoring do indeed experience debilitating long-lasting neuropsychological deficits21. The goal of the present paper is thus to contribute to our knowledge about the frequency and nature of the neuropsychological risks when operating IDH-mutated glioma in the right frontal lobe.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

We retrospectively reviewed our consecutive database of cases operated on in awake condition since 2011. We selected all cases with an IDH-mutated glioma located in the right frontal lobe. Clinical and radiological data were retrieved through electronic medical files and the Picture and Archiving Communication System (PACS), respectively.

Operative techniques

Monitored anesthesia care, which consists of sedation while preserving spontaneous ventilation without any airway instrumentation, was used during the nonawake periods22. Sedation was achieved by a mixture of propofol and remifentanil, with additional use of dexmedetomidine in the last cases. Patients were prepared through a systematic protocol that includes hypnotic techniques23,24.

All cases were operated on by the senior author, with the naked eye (cases 1–8) or surgical loops (cases 10–20). Surgical microscope was used for case 9. Electrical stimulation was used as previously reported25,26,27. Monitoring was performed by a speech therapist (MB, IP, SL, CPT) and, on surgeon’s request, assessed motor functions (continuous repetitive movement of left superior limb), counting, picture object naming, nonverbal semantic association, and the test “read the mind in the eyes”. Resection was stopped when a functional boundary was encountered.

Imaging

All patients underwent the same imaging protocol, as previously described25,27,28. In this study, the extent of resection was estimated on FLAIR sequences and computed as 100 × (1 − residual volume/initial volume). Surgical cavities were segmented with MI-Brain 2020.04.09 software29 (Sherbrooke, Canada, https://github.com/imeka/mi-brain) on 3D-T1 images and resized to a resolution of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3. Images were then registered to the MNI template using the Antsregistration algorithm and displayed with MRIcro-GL 1.2.20201102 software30 (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl/). In cases 8, 11, 13–20, language fMRI was performed to confirm the left lateralization of language networks, following the same methodology as previously reported12.

Neuropsychological testing

Patients were thoroughly evaluated neuropsychologically by a speech therapist (MB, IP, SL, CPT) just before, immediately after, and four months after the surgery. After a short non-structured interview with the patient, aiming to record spontaneous complaints, the evaluation assessed language, memory, executive and visuospatial functions, and social cognition. The most common tests were administered to all patients, whereas some tests were added in a patient-specific approach, as expected for evaluations performed in a clinical rather than research context.

Language and semantic cognition testing included:

-

DO 80 picture naming31,

-

Complex language functions including word definitions, word evocation on definition, concatenation of sentences, synonym evocation, antonym evocation and odd word out selection from the TLE32 and some parts of the BDAE33,

-

Writing and reading from the ECLA34,

-

Understanding of implicit metaphors from the MEC35,

-

Categorical and literal fluencies (2 min)36,

-

Nonverbal semantic association (pyramid and palm tree test—PPTT—37, or BEC-S in the very last patients38.

Tasks tapping attention and executive functions comprised:

-

Forward and backward digit span (testing working memory)39,

-

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) (testing working memory and sustained attention)40,

-

Trail-making test, part A & B (testing mental flexibility)36,

-

Stroop test (testing inhibition)41,

-

d2-attention test (testing sustained attention)42,

-

Copy of the Rey figure (testing visuospatial praxies)43.

Visuospatial cognition was assessed by line bisection, Bells’ and Clock’s tests and writing44. Memory was evaluated through delayed copy of the Rey figure and RI-RL 16 task45 (or RI 48 in the very first patients46). Finally, social cognition was evaluated with the Read the Mind in the Eyes test47, facial emotion recognition48,49, and faux pas recognition49,50.

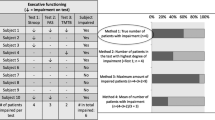

For each patient, speech therapists wrote a synthetic conclusion summarizing the patient’s performance in terms of nosological entities (deficits of executive functions, attention disorder, short-term memory impairment, etc.). In the results section, we listed for each patient and for each evaluation the key words retrieved from these conclusions. We claim that this approach allows us to obtain a picture of patients’ functions that is easier to grasp and interpret than the full set of raw psychometric scores. The main scores and their corresponding z-scores are nonetheless also given at the group level. Moreover, z-scores were used to categorize each patient as having a long-term impairment in one domain when at least one test z-score of that domain decreased by 1.5 units or more.

Statistical methods

Differences between pre and postop scores were assessed using paired test. Normality of these differences was checked using Shapiro test. For normal data, we used a paired Student’s t-test. For non-normal data, we used a paired Wilcoxon test. Significance was set at a p value of 0.05. All analysis were performed with R51 under R studio software52.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee of Lariboisière Hospital and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. The study was approved by the local ethics committee Pôle Neurosciences of Lariboisière hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Patients characteristics

Twenty surgical cases in eighteen patients (two patients operated on twice) were included in the study. There were 6 females and 12 males. Among the 20 cases, 5 were redo surgeries. Symptoms motivating the first MRI were generalized seizures in 13 out of 18 patients and persisting headaches in one patient. Radiological discovery was incidental in 4 patients. Median age at surgery was 42.5 years (range 26–58). All patients were right-handed, except one patient (case 5) who was ambidextrous. Left lateralization of language networks was confirmed in the 10 patients in whom fMRI was performed. Patients were working at the time of their surgery in seventeen out of twenty cases. Four patients received an adjuvant treatment (two chemotherapy and two concomitant chemo-radiotherapy) within the four months interval between surgery and neuropsychological evaluation. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Tumor characteristics

The median preoperative volume was 37 cc (mean 51 cc, range 1.7–175 cc). Preferential locations were the posterior part of the superior frontal gyrus (SFG), followed by the anterior frontal lobe, the middle frontal gyrus (MFG), and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG). Contrast enhancement was present in 4 cases. Histopathological examination revealed a grade II in 70% of cases (1/3 of 1p-19q co-deleted oligodendroglioma, 2/3 of astrocytoma), a grade III in 20% of cases (all 1p-19q co-deleted oligodendroglioma) and a glioblastoma in 10% of cases. Tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Surgical results

The mean extent of resection was 93% (range 37.5–100%), and the mean residual volume was 4.9 cc (range 0–40 cc). Resections were complete in 55% of surgeries. Figure 1 shows the surgical cavities after registration to the MNI template.

None of the patients presented long-lasting postoperative motor deficits. Two patients presented incomplete akinesia, which resolved within a couple of days. This akinesia affected both the upper and lower extremities (case 2) or only the upper extremity (case 10). One patient (case 1) had an epidural hematoma requiring evacuation at postoperative day 3. One patient (case 15) had a wound infection requiring bone flap removal 3 months after the surgery and a cranioplasty 6 months later.

Mapping results

All mapping results are given in Table 2 and Fig. 2. For all 19 patients in whom the precentral gyrus was exposed, stimulation generated positive motor responses. Sites generating motor arrest (of speech and/or of upper limb movement) were seen in 12 cases. No reproducible cortical sites were found when monitoring nonverbal semantic association (PPTT) or emotion recognition (RME). When stimulating the white matter, positive motor responses were seen in 5 cases (upper limb on 1 site, lower limb in 5 sites). White matter sites of upper extremity motor arrest were observed in 12 cases. Eye movements with loss of contact were noted in 3 cases. No reproducible sites were found when testing the PPTT or RME. Finally, stimulation of white matter generated in two patients (cases 17 and 19) made it impossible to perform the 1-back naming task combined with continuous repetitive movement of the upper extremity. In both cases, patients spontaneously reported an attentional disorder: one patient said ‘I do not know, I did not pay attention’, and the other said ‘I do not know, I did not see the last image’.

Group-level analysis of neuropsychological quantitative evaluations

Table 3 gives the quantitative means of the raw scores and z-scores for picture naming, Rey figure copy, digit span forward and backward, verbal fluencies, Trail Making Test (B-A), Stroop (conflict), and Bells’ test. Preoperatively, all z-score means were in the normal range (> − 1.0), in accordance with almost normal cognitive functioning in IDH-mutated glioma patients. In the immediate postoperative period, a statistically significant (p < 0.05) deterioration was observed for DO80, Rey figure, verbal fluencies, TMT B-A, Stroop test and Bells’ test. At the late postoperative evaluation, only categorical fluency significantly differed from its preoperative value (mean 33.1 postop vs 36.3 preop).

Individual-level analysis of preoperative neuropsychological evaluation

Preoperatively, patients rarely reported spontaneous cognitive or behavioral disorders. (see Table 4). The most common complaints were distractibility (30% of cases), followed by fatigability (20%) and irritability (15%). Neuropsychological evaluations demonstrated mild deficits (see Table 5). These deficits impacted executive functions in 45% of cases, attention in 45% of cases, and verbal short-term memory in 45% of cases. Speed processing was also slightly below the average in 50% of cases. Of note, difficulties with high-level semantic cognition (conceptualizing or grasping implicit) were observed in 20% of cases.

Individual-level analysis of immediate postoperative evaluation

At the immediate (within one week postsurgery) postoperative evaluation, 75% of cases had marked deficits in executive functions (see Table 5). Attention capabilities were also strongly impacted in 65% of cases. Left unilateral spatial neglect (USN) was detected in 60% of cases. Behavioral disturbances included apathy (30% of cases), aprosodia/amimia (45% of cases), and emotional sensitivity (10% of cases). Of note, anosognosia was observed in 25% of cases.

Individual-level analysis of postoperative neuropsychological evaluation

All but 4 patient cases underwent intensive cognitive rehabilitation for a period of four months. Patients performed this cognitive training in the outpatient speech therapy clinics nearest to their home.

At 4 months postsurgery, the complaints most commonly reported by patients were fatigability (65% of cases), distractibility (45% of cases) and difficulties coping with multitasking (30% of cases) (see Table 4). Uncommon complaints included reduced speed processing, lack of motivation, difficulties with time (either for time perception or for schedule management), urinary urgency, irritability, mood disorder, loss of bimanual coordination, language disorder and sleep disorder. Objective neuropsychological evaluations confirmed these self-reported lamentations (see Table 5). Executive abilities and attention were the main affected functions, together with verbal short-term memory. Interestingly, signs of USN almost completely resolved (two patient cases with very mild persisting signs of left USN). Importantly, a small proportion of patients had persistent disorders of high-level semantic cognition (grasping implicit or metaphors) and/or an impairment of social cognition. Overall, when comparing the pre- and postoperative evaluations, 9 out of 20 cases demonstrated decreased performance in at least one domain among executive functions, speed processing, attention, spatial cognition, semantic cognition, and social cognition.

Clinical follow-up

Out of the seventeen patients working at the time of surgery, twelve (70%) resumed their professional activity within 6 months after the surgery. All patients but one were alive at the time of last follow-up: one patient (case 10) died after 3 years of glioma evolution. Median follow-up was 42 months (range 12–102 months).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to provide a comprehensive overview of the cognitive dysfunctions that might remain four months after awake resection of IDH-mutated glioma located to the right frontal lobe. Such knowledge can help neurosurgeons better inform their patients about the (mild) cognitive risks that come with resection of a right frontal IDH-mutated glioma. We would like to put our results in perspective with the previous literature.

Motor control

In the present series, only two patients experienced transient akinesia, which is typical of SMA syndrome. For both of them, akinesia occurred intraoperatively before sites of motor arrest could be properly identified. In all other patients, such sites were detected and preserved, thus avoiding transient postoperative akinesia, as previously reported53. It should be emphasized that it is now recognized that the recovery of SMA syndrome is incomplete and that disorders of fine motor movements might persist, in particular regarding bimanual coordination, a subjective complaint reported by one patient (case 2). Of note, two patients also reported urge incontinence, as previously observed54. These symptoms hampered their quality of life but improved under 5 mg solifenacine succinate twice daily.

Neuropsychological outcomes: group-level analysis

Our group-level analysis could not capture the mild long-term deficits encountered in this selected group of patients (except for a slight decrease in categorical fluency). Although we cannot rule out that this is due to the small size of the series, such a result is in good accordance with the high level of recovery observed in this patient population (thanks to the efficient implementation of plasticity mechanisms)55. It can be hypothesized that such favorable cognitive outcomes—in spite of a large extent of resection—were achieved thanks to intraoperative mapping relying on tasks tapping cognitive control abilities. As an alternative hypothesis, averaging at the group level might have balanced improved and deteriorated patients’ scores. Hence, we next investigated evaluations at the individual level by analyzing patients’ self-reported complaints, quantitative changes in psychometric z-scores, and objective qualitative conclusions found in the written reports of the speech therapists.

Neuropsychological outcomes: individual-level analysis

Very few studies have preoperatively explored the cognitive functioning of patients with right frontal glioma, and even fewer have reported subjective complaints, as explained by the patients themselves. Eight out of the fifteen patients with an incidental glioma studied by Cochereau et al.56 had a tumor located in the right frontal lobe. Five out of the eight had subjective complaints, including tiredness, altered attention, and irritability. Our results are perfectly in line with this study, as fatigability, distractibility and irritability were reported by 20, 30 and 15% of patients in our series, respectively (see Table 4). Objective evaluations demonstrated deficits in working memory and/or executive functions in four out of the eight patients reported by Cochereau et al. Similarly, we found that executive functions, short-term working memory, and attention were the most commonly impacted domains, with almost half of the patients being affected (see Table 5). It is worth emphasizing that these deficits were very mild, in accordance with the high rate of patients with professional activity just before the surgery (17 out of 20 patient cases). Interestingly, impairments of high-level semantic cognition (grasping metaphors or implicit) were diagnosed in 20% of cases. Such troubles have been previously reported after resection of right hemispheric glioma57 and deserve further specific investigations. Of note, we found a low rate of preoperative disturbance in social cognition, which is also in line with a recent report20.

While almost every patient presented cognitive deterioration at the immediate postoperative evaluations, slight impairment in at least one domain (among executive functions, attention, speed processing, spatial cognition, semantic cognition, or social cognition) was detected at the four-month evaluation in only 9 cases out of 20. Nonetheless, the decline was slight enough that a remarkably high proportion (70%) of patients working preoperatively could resume their work within six months after the surgery. Again, this good outcome suggests that awake cognitive mapping could have contributed to preserving the patients’ socioprofessional life.

Our results are in line with a previous study58 reporting a decline in executive functions and/or speed processing and/or attention in 32% of cases (both left and right hemispheres). Resection map symptom mapping highlighted the right frontal lobe as being the location most at risk58. Such results were further confirmed by studies in 77 low-grade glioma patients, including 27 cases of right frontal location59: preoperative impairments in verbal memory, finger tapping, symbol digit coding, cognitive flexibility, verbal fluency and sustained attention were observed, with further deterioration at three months for sustained attention. Two other recent studies also emphasized the risk regarding inhibition capabilities (as measured by Stroop’s task) when operating in the right frontal lobe19,60. Regarding visuospatial cognition, long-lasting left USN was found in one-third of patients in whom resection of right hemispheric tumors encompassed the SFG and MFG18. In our series, whereas USN was found in 60% of cases in the immediate postoperative period, mild signs of USN were found in only 10% of cases four months later (in particular, none of the patients deviated at the line bisection task). To explain the difference between the two series, it is tempting to put forward the following hypothesis, already mentioned in18: persistent deficits would be caused by the cumulative effect of resecting both the first and second branches of the superior longitudinal fasciculus, a situation that might have been less frequent in the present series.

Performances in social cognition declined in two patients, in accordance with a previous report61. It should be noted that we failed to identify reproducible stimulation sites disturbing the RME task, contrary to previous reports20,62. The lack of experience of the team regarding this kind of mapping likely explains this difference. An alternative explanation could be that the stimulated area is too small compared to the cortical area supporting the function. This latter hypothesis could be tested by simultaneously stimulating two sites, as recently suggested63. Similarly, we found no reproducible sites when testing the nonverbal semantic association task (PPTT), contrary to previous reports64,65. It can be hypothesized that the identification of such sites would have contributed to preventing the postoperative semantic cognition disorders (implicit and/or metaphors understanding) found in three cases.

Finally, objective evaluations and subjective complaints overlapped only partially. Some dysfunctions reported by patients were indeed not captured by the battery of tasks we used. Such functions include fatigability, irritability, or multitasking. Specific tasks should be designed to objectify and quantify these kinds of impairments.

Limitations

Finally, our study has several limitations, including all those that come with a retrospective design and a small sample size, making it difficult to generalize definitive conclusions. However, the fact that cases were consecutively reported and that the management was the same for all patients partly compensated for these limitations. Mixing histological grade might have blurred the results, as grade might interfere with neuroplasticity capabilities. However, as we selected only IDH-mutated glioma, this variability was strongly reduced. Indeed, in our subgroup of patients—and even in case of grade IV-, the tumor remained under control for several months after surgery and postoperative adjuvant treatment, hence providing a large time window for plasticity implementation. The cognitive evaluations were performed by four different speech therapists, and this might have introduced heterogeneity in the qualitative reports, but this is compensated by the extensive quantitative data of our test battery. Furthermore, patients were evaluated only at 4 months, so we cannot rule out that a different pattern of deficits would have been seen one year later. However, there are some data in the literature demonstrating that, in general, the cognitive recovery curve reaches a plateau after 4 months (see, for example66, for spatial attention and awareness). Hence, although this is not proven, we made the reasonable assumption that the 4-month measure is a good proxy of the 1-year measure. Last but not least, the small size of our series did not allow us to perform a multivariate analysis that would have included all regressors known to influence cognitive recovery, including age, preoperative cognitive status, somatic gene polymorphisms67, location and extent of resection, and growth rate of residual tumor. We thus emphasize the need to share data between centers to address such important questions.

Conclusion

Overall, the present study supports the idea that the right frontal lobe should be considered a highly eloquent area, given the high rate of persistent mild neuropsychological impairments found 4 months after surgery. There is still much to do to better understand the neuronal networks sustaining these high-level functions and, most importantly, to better understand how resection will impact those networks, in particular for differentiating damages that will be restorable through plasticity-mediated reorganization from those that will overwhelm the potentialities of plasticity and cause definitive deficits. This is a real challenge, considering the high degree of individual variability of topographical organization and plasticity of cognitive networks and meta-networks68,69,70,71. Finally, the encouraging high rate of work resumption gives support to the assumption that awake surgery could have a positive impact on the patients’ socioprofessional life: intraoperative monitoring of executive functions, semantic cognition and social cognition in an awake patient might be currently the best method to preserve these functions, thus giving to each individual patient the best chances to return to a normal socioprofessional life. Such an assumption deserves confirmation from future studies with larger samples.

References

Capelle, L. et al. Spontaneous and therapeutic prognostic factors in adult hemispheric World Health Organization Grade II gliomas: A series of 1097 cases—Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 118(6), 1157–1168 (2013).

Chang, E. F. et al. Preoperative prognostic classification system for hemispheric low-grade gliomas in adults. J. Neurosurg. 109(5), 817–824 (2008).

Jakola, A. S. et al. Comparison of a strategy favoring early surgical resection vs a strategy favoring watchful waiting in low-grade gliomas. JAMA 308(18), 1881–1888 (2012).

Roelz, R. et al. Residual tumor volume as best outcome predictor in low grade glioma: A nine-years near-randomized survey of surgery vs. biopsy. Sci. Rep. 6, 32286 (2016).

Garton, A. L. A. et al. Extent of resection, molecular signature, and survival in 1p19q-codeleted gliomas. J. Neurosurg. 134, 1357–1367 (2020).

Jakola, A. S. et al. Surgical resection versus watchful waiting in low-grade gliomas. Ann. Oncol. 28(8), 1942–1948 (2017).

Wijnenga, M. M. J. et al. The impact of surgery in molecularly defined low-grade glioma: An integrated clinical, radiological, and molecular analysis. Neuro-oncology 20(1), 103–112 (2018).

Duffau, H. Preserving quality of life is not incompatible with increasing overall survival in diffuse low-grade glioma patients. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 157(2), 165–167 (2015).

Duffau, H. & Mandonnet, E. The “onco-functional balance” in surgery for diffuse low-grade glioma: Integrating the extent of resection with quality of life. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 155(6), 951–957 (2013).

Mandonnet, E. & Duffau, H. An attempt to conceptualize the individual onco-functional balance: Why a standardized treatment is an illusion for diffuse low-grade glioma patients. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 122, 83–91 (2018).

Mandonnet, E., Duffau, H. & Bauchet, L. A new tool for grade II glioma studies: Plotting cumulative time with quality of life versus time to malignant transformation. J. Neurooncol. 106(1), 213–215 (2012).

Mandonnet, E. et al. When right is on the left (and vice versa): A case series of glioma patients with reversed lateralization of cognitive functions. J. Neurol. Surg. A Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 81(2), 138–146 (2020).

Foster, C. H., Morone, P. J. & Cohen-Gadol, A. Awake craniotomy in glioma surgery: Is it necessary?. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 63(2), 162–178 (2019).

De Witt Hamer, P. C., Robles, S. G., Zwinderman, A. H., Duffau, H. & Berger, M. S. Impact of intraoperative stimulation brain mapping on glioma surgery outcome: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 30(20), 2559–2565 (2012).

Bernard, F., Lemée, J.-M., Ter Minassian, A. & Menei, P. Right hemisphere cognitive functions: From clinical and anatomic bases to brain mapping during awake craniotomy. Part I: Clinical and functional anatomy. World Neurosurg. 118, 348–359 (2018).

Lemée, J.-M., Bernard, F., Ter Minassian, A. & Menei, P. Right hemisphere cognitive functions: From clinical and anatomical bases to brain mapping during awake craniotomy. Part II: Neuropsychological tasks and brain mapping. World Neurosurg. 118, 360–367 (2018).

Vilasboas, T., Herbet, G. & Duffau, H. Challenging the myth of right nondominant hemisphere: Lessons from corticosubcortical stimulation mapping in awake surgery and surgical implications. World Neurosurg. 103, 449–456 (2017).

Nakajima, R. et al. Damage of the right dorsal superior longitudinal fascicle by awake surgery for glioma causes persistent visuospatial dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 17158 (2017).

Puglisi, G. et al. Frontal pathways in cognitive control: Direct evidence from intraoperative stimulation and diffusion tractography. Brain 142(8), 2451–2465 (2019).

Yordanova, Y. N., Duffau, H. & Herbet, G. Neural pathways subserving face-based mentalizing. Brain Struct. Funct. 222(7), 3087–3105 (2017).

Mandonnet, E., Herbet, G. & Duffau, H. Letter: Introducing new tasks for intraoperative mapping in awake glioma surgery—Clearing the line between patient care and scientific research. Neurosurgery 86(2), E256–E257 (2020).

Arzoine, J. et al. Anesthesia management for low-grade glioma awake surgery: A European Low-Grade Glioma Network survey. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 162(7), 1701–1707 (2020).

Aubrun, S. et al. The challenge of overcoming the language barrier for brain tumor awake surgery in migrants: A feasibility study in five patient cases. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 162(2), 389–395 (2020).

Madadaki, C. et al. Reply to: Letter to the editor regarding anesthesia management for low-grade glioma awake surgery—A European Low-Grade Glioma Network survey. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 162(7), 1723–1724 (2020).

Corrivetti, F. et al. Dissociating motor-speech from lexico-semantic systems in the left frontal lobe: Insight from a series of 17 awake intraoperative mappings in glioma patients. Brain Struct. Funct. 224(3), 1151–1165 (2019).

Mandonnet, E. et al. Initial experience using awake surgery for glioma: Oncological, functional, and employment outcomes in a consecutive series of 25 cases. Neurosurgery 76(4), 382–389 (2015).

Mandonnet, E. et al. “I do not feel my hand where I see it”: Causal mapping of visuo-proprioceptive integration network in a surgical glioma patient. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 162(8), 1949–1955 (2020).

Mandonnet, E. et al. A network-level approach of cognitive flexibility impairment after surgery of a right temporo-parietal glioma. Neurochirurgie 63(4), 308–313 (2017).

Rheault, F., Houde, J., Goyette, N., Morency, F. & Descoteaux, M. MI-Brain, a software to handle tractograms and perform interactive virtual dissection (2016).

Rorden, C. & Brett, M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behav. Neurol. 12(4), 191–200 (2000).

Metz-Lutz, M. et al. Standardisation d’un test de dénomination orale: Contrôle des effets de l’âge, du sexe et du niveau de scolarité chez les sujets adultes normaux. Rev. Neuropsychol. 1, 73–95 (1991).

Rousseaux, M. & Dei Cas, P. Test de Langage Elaboré pour Adultes (Ortho Editions, 2012).

Goodglass, H., Kaplan, E. & Barresi, B. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination 3rd edn. (PRO-ED, 2000).

CogniSciences | Outils | ÉCLA-16+ (accessed 2 February 2021); http://www.cognisciences.com/accueil/outils/article/ecla-16.

Ferré, P., Lamelin, F., Côté, H., Ska, B. & Joanette, Y. Protocole Montréal d’Evaluation de la Communication (Protocole MEC) (Ortho Edition, 2011).

Godefroy, O. et al. Dysexecutive syndrome: Diagnostic criteria and validation study. Ann. Neurol. 68(6), 855–864 (2010).

Howard, H. & Patterson, K. The Pyramidal and Palm Tree Test (Themes Valley Test Company, 1992).

Merck, C. et al. La batterie d’évaluation des connaissances sémantiques du GRECO (BECS-GRECO): validation et données normatives. Rev. Neuropsychol. 3(4), 235–255 (2011).

GrÉGoire, J. & Linden, M. V. D. Effect of age on forward and backward digit spans. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 4(2), 140–149 (1997).

Gronwall, D. M. Paced auditory serial-addition task: A measure of recovery from concussion. Percept. Mot. Skills 44(2), 367–373 (1977).

Stroop, J. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 6, 643–662 (1935).

Brickenkamp, R. Test d2: Aufmerksamkeits-Belastungs-Test (Test d2: Concentration-Endurance Test: Manual) (Verlag fur Psychologie, 1981).

Rey, A. L’examen psychologique dans les cas d’encéphalopathie traumatique. Arch. Psychol. 28, 328–336 (1941).

Batterie d’évaluation de la négligence unilatérale: BEN (Ortho Edition, 2002).

Grober, E., Buschke, H., Crystal, H., Bang, S. & Dresner, R. Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology 38(6), 900–903 (1988).

Adam, S., Van der Linden, J. & Poitrenaud, J. L’épreuve de rappel indicé à 48 items (RI-48). L’évaluation des troubles de la mémoire. Neuropsychologie (Solal, 2004).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The “reading the mind in the eyes” test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 42(2), 241–251 (2001).

Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. Pictures of Facial Affect (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976).

Funkiewiez, A., Bertoux, M., de Souza, L., Lévy, R. & Dubois, B. The SEA (Social cognition and Emotional Assessment): A clinical neuropsychological tool for early diagnosis of frontal variant of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neuropsychology 26(1), 81–90 (2011).

Stone, V. E., Baron-Cohen, S. & Knight, R. T. Frontal lobe contributions to theory of mind. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 10(5), 640–656 (1998).

R Core T. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Core Team, 2021).

RStudio T. RStudio: Integrated Development for R (RStudio, 2020).

Rech, F. et al. Intraoperative identification of the negative motor network during awake surgery to prevent deficit following brain resection in premotor regions. Neurochirurgie 63(3), 235–242 (2017).

Duffau, H. & Capelle, L. Incontinence after brain glioma surgery: new insights into the cortical control of micturition and continence. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 102(1), 148–151 (2005).

Krishna, S., Kakaizada, S., Almeida, N., Brang, D. & Hervey-Jumper, S. Central nervous system plasticity influences language and cognitive recovery in adult glioma. Neurosurgery 89, 539–548 (2021).

Cochereau, J., Herbet, G. & Duffau, H. Patients with incidental WHO grade II glioma frequently suffer from neuropsychological disturbances. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 158(2), 305–312 (2016).

Skrap, M., Marin, D., Ius, T., Fabbro, F. & Tomasino, B. Brain mapping: A novel intraoperative neuropsychological approach. J. Neurosurg. 125, 877–887 (2016).

Hendriks, E. J. et al. Linking late cognitive outcome with glioma surgery location using resection cavity maps. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39(5), 2064–2074 (2018).

Rijnen, S. J. M. et al. Cognitive functioning in patients with low-grade glioma: Effects of hemispheric tumor location and surgical procedure. J. Neurosurg. 133, 1671–1682 (2019).

Niki, C. et al. Primary Cognitive Factors Impaired after Glioma Surgery and Associated Brain Regions. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 7941689 (2020).

Herbet, G., Lafargue, G., Bonnetblanc, F., Moritz-Gasser, S. & Duffau, H. Is the right frontal cortex really crucial in the mentalizing network? A longitudinal study in patients with a slow-growing lesion. Cortex 49(10), 2711–2727 (2013).

Herbet, G., Lafargue, G., Moritz-Gasser, S., Bonnetblanc, F. & Duffau, H. Interfering with the neural activity of mirror-related frontal areas impairs mentalistic inferences. Brain Struct. Funct. 220(4), 2159–2169 (2015).

Gonen, T. et al. Intra-operative multi-site stimulation: Expanding methodology for cortical brain mapping of language functions. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180740 (2017).

Herbet, G., Moritz-Gasser, S. & Duffau, H. Direct evidence for the contributive role of the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus in non-verbal semantic cognition. Brain Struct. Funct. 222(4), 1597–1610 (2017).

Herbet, G., Moritz-Gasser, S. & Duffau, H. Electrical stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex impairs semantic cognition. Neurology 90(12), e1077–e1084 (2018).

Ramsey, L. E. et al. Normalization of network connectivity in hemispatial neglect recovery. Ann. Neurol. 80(1), 127–141 (2016).

Altshuler, D. B. et al. BDNF, COMT, and DRD2 polymorphisms and ability to return to work in adult patients with low- and high-grade glioma. Neurooncol. Pract. 6(5), 375–385 (2019).

Duffau, H. A two-level model of interindividual anatomo-functional variability of the brain and its implications for neurosurgery. Cortex 86, 303–313 (2017).

Herbet, G. Should complex cognitive functions be mapped with direct electrostimulation in wide-awake surgery? A network perspective. Front. Neurol. 12, 635439 (2021).

Herbet, G. & Duffau, H. Revisiting the functional anatomy of the human brain: Toward a meta-networking theory of cerebral functions. Physiol. Rev. 100(3), 1181–1228 (2020).

Mandonnet, E. Should complex cognitive functions be mapped with direct electrostimulation in wide-awake surgery? A commentary. Front. Neurol. 12, 721038 (2021).

Acknowledgements

EM was supported by INSERM, contrat interface 2018.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., I.P., V.F., S.L., C.P.T. contributed to data collection. E.M. analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barberis, M., Poisson, I., Facque, V. et al. Group-level stability but individual variability of neurocognitive status after awake resections of right frontal IDH-mutated glioma. Sci Rep 12, 6126 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08702-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08702-2

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Verbal fluency predicts work resumption after awake surgery in low-grade glioma patients

Acta Neurochirurgica (2024)

-

An update on tests used for intraoperative monitoring of cognition during awake craniotomy

Acta Neurochirurgica (2024)

-

Performance of intraoperative neurocognitive tests during awake surgery for patients with diffuse low-grade glioma

Neurosurgical Review (2024)

-

Oncological and functional outcomes support early resection of incidental IDH-mutated glioma

Acta Neurochirurgica (2023)