Abstract

Antiretroviral therapy lowers viral load only when people living with HIV maintain their treatment retention. Lost to follow-up is the persistent major challenge to the success of ART program in low-resource settings including Ethiopia. The purpose of this study is to estimate time to lost to follow-up and its predictors in antiretroviral therapies amongst adult patients. Among registered HIV patients, 542 samples were included. Data cleaning and analysis were done using Stata/SE version 14 software. In multivariable Cox regression, a p-value < 0.05 at 95% confidence interval with corresponding adjusted hazards ratio (AHR) were statistically significant predictors. In this study, the median time to lost to follow-up is 77 months. The incidence density of lost to follow-up was 13.45 (95% CI: 11.78, 15.34) per 100 person-years. Antiretroviral therapy drug adherence [AHR: 3.04 (95% CI: 2.18, 4.24)], last functional status [AHR: 2.74 (95% CI: 2.04, 3.67)], and INH prophylaxis [AHR: 1.65 (95% CI: 1.07, 2.56) were significant predictors for time to lost to follow-up. The median time to lost was 77 months and incidence of lost to follow-up was high. Health care providers should be focused on HIV counseling and proper case management focused on identified risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) which potentially leads to Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is a global health problem1,2,3,4. Globally, an estimated 37.7 million (30.2 million–45.1 million) people were living with HIV and around 4,000 new infections every day, 20205,6. Africa, Asia, and Latin America were the major affected continents by HIV infection5,7,8. In 2020, more than 680, 000 deaths and destroyed 21.5 US dollars for ADIS response in low and middle-income countries6. Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) lowers viral load only when people living with HIV (PLHIV) fully adhere to the treatment regimen continuously for life3,9,10,11. However, the viral suppression rate was 66% globally, 59% in western and central Africa, and 72% in Ethiopia in 20205,6. Optimal HIV care retention is very crucial to address HIV global 2030 goals5,12.

Lost to follow-up is defined as a patient who has not received ART medication for more than 30 days of their last missed drug collection appointment8,13,14,15. Lost to follow-up is the persistent major challenge to the success of the ART programs in low-resource settings including Ethiopia2,8,10,16,17. This may increase treatment failure (i.e. clinical, immunological, and Virological), morbidity, mortality, and drug resistance7,8,10. The patient retention status is an important measurement of ART program effectiveness7,10. In the previous finding in Asia, the trend of lost to follow-up among HIV- positive patients’ received ART was 9%18. In sub-Saharan Africa, public sector HIV treatment clinics five years retrospective follow-up revealed that 24.6% were lost to follow-up10. The proportion of lost to follow-up was found to range in different settings from 16.4%19 in South Africa, 28% in Nigeria, 12.4%20 in Malawi, and 3% in seven teaching hospitals, 11% in Wukro Hospital in Tigray Region, Ethiopia, and 21.3% in Oromia Region, Ethiopia2,9,15,21,22,23. In resource-limited settings of West Africa, males had a 14% higher rate of lost than females. The incidence rate of lost to follow-up was 9.2/100 person-years (PYs)23 in a large-scale ecological study in Sub-Saharan Africa. Other studies found rates of 12.8%/100 PYs15 in South Africa, 11.6/100PYs24 in Pawi General Hospital in Ethiopia, 8.2/100 PYs in Aksum Hospital13, and 12.26/100 PYs25 in Gondar Specialized Comprehensive Hospital in Ethiopia. The median time to lost to follow-up was three months, and 14% of them had lost in the first day of antiretroviral therapy26.

The findings in Nigeria showed the incidence rate of treatment interruption was highest in the first six months of ART at 18.2/100 PYs but decreased after two years to 8.8/100 PYs. Lost to follow-up from treatment increased by 1.30 times for each calendar year in a study in South Africa15. Previous existing evidence revealed, patients who had hemoglobin (Hgb) markers, nutritional deficiencies, opportunistic infections, cancers, illiterate, unmarried, rural dweller, alcohol drank, tobacco smoking, CD4 level, WHO clinical stage, short HIV infection history, age, drug side effect, viral load, employment status, regimen change, TB infection, male gender, weight, mental illness, receiving INH therapy, functional status, and advanced HIV disease affecting the hematopoietic system were predictors of lost to follow-up7,8,11,13,24,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34.

Previously shared evidence, in Ethiopia, addresses adherence to ART and only a few studies were conducted to assess predictors of lost to follow-up. However, the data regarding time to lost to follow-up after ART initiation, incidence lost follow-up, and predictors were unsaturated. Therefore, this study aims to estimate the time to lost to follow-up and its predictors among adult patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Amhara, Northwest Ethiopia.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

A total of 542 participants were included in the study. More than half (60.5%) of participants were females. The mean age of participants was 34.34 ± 10.49 years standard deviation. Two hundred sixty-six (49%) patients were married and 66 (12.2%) of the partners were known to be HIV-positive. In this study, two-third (66.8%) of study participants had disclosed their HIV-positive status. Almost one-fourth (27.5%) of study subjects had used family planning during the study period, with 37 (6.8%) of them using natural family planning methods and only 29 (8.8%) study participants had become pregnant in this follow-up period (Table 1).

Medical history, clinical, and drug adherence characteristics

In this study, 66 (12%) and 105 (19.4%) of participants had a history of diarrhea and fever respectively. Two hundred (36.9%) study participants had a history of opportunistic infection and 83 (15.3%) of participants had taken INH preventive therapy. Only (53%) of study participants had Hgb tested during their enrolment. The median CD4 level of study participants was 208cells/mm3 with IQR (106–328.25) (Tables 2 and 3).

Lost follow-up status and treatment outcome

Of the 542 study participants, 221 (40.8%) (95% CI: 36.69, 44.98) were lost to follow-up, nearly one-third (32.5%) were on active treatment, 20.1% were transferred out, and 6.6% died in this retrospective follow-up cohort.

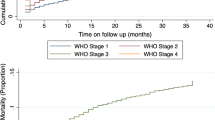

The incidence density of lost to follow-up was 13.45 (95% CI: 11.78, 15.34) per 100 PYs. In this finding, half of the patients had lost to follow-up at 77 months follow-up (95% CI: 51, 107) period (Fig. 1).

The incidence rate of lost to follow-up is quite different based on duration point in treatment as 3.32/100 person-months at first month, 5.20/100 person-months at second month, 3.11/100 person-months at 3 months, and 2.20/100 person-months at 6 months after ART treatment initiation. Even though the incidence density in the first-year follow-up is high, it shows a general pattern of declines over the first-six years follow-up as 27.41/100PYs at 1st year, 13.87/100PYs at 2nd year, 9.82/100PYs at 3rd year, 8.45PYs at 4th year, 6.04PYs at 5th year, and 4.18PYs at 6th year. Controversially, the incidence of lost to follow-up was high, 7.3/100PYs at the end of the 9th year follow-up.

Predictors of time to lost to follow-up among adult HIV patients

In multivariable Cox regression analysis, statistically significant variables were selected. Patients who had poor ART drug adherence were three times more at risk of lost to follow-up compared to the cohort with good ART drug adherence [AHR: 3.04 (95% CI: 2.18, 4.24)]. Similarly, those who had ambulatory or less last functional status were 2.74 times more at risk to lost to follow-up compared to working last functional status [AHR: 2.74 (95% CI: 2.04, 3.67)]. Moreover, patients not receiving INH prophylaxis therapy were 1.65 times more at risk to lost to follow-up compared to counterparts taking INH therapy [AHR: 1.65 (95% CI: 1.07, 2.56)] (Table 4 and Figs. 2, 3 and S2).

Discussion

This study was designed to estimate time to lost to follow-up among adult HIV/AIDS patients. ART declines HIV/AIDS-related death, hence high retention in ART care is required to optimize treatment outcomes2,23,34,35. In this study, the overall incidence density of lost to follow-up was 13.45 (95% CI: 11.78, 15.34) per 100 PYs. The study finding is similar to previous evidence with 12.26/100PYs25 in Gondar Specialized Hospital in Ethiopia and 12.8/100PYs15 in South Africa. The current finding is greater than the 10.9/100 PYs in Gondar Specialized Hospital Ethiopia34, 11.6/100 PYs in Pawi Hospital (Northwest Ethiopia)24, and 9.2/100 PYs in a large scale ecological study in sub-Saharan Africa23. The possible reason for this variation might reflect differences in the study period, settings, sample size, adherence problem, drug-related side effects, and counseling barriers. As evidence revealed, the quality of clinical service care was different between different levels of health facilities this may have a role on lost to follow-up36. This study was conducted in a single health center that has poor health care service (such as lack of medical equipment, inadequate laboratory investigations, poor case management, lack of senior clinicians, and high turnover rate of health professionals), poor health-seeking behaviors, lengthy travel distances to get health service, and low literacy levels this might be increase likely hood of lost to follow-up. Even though limited evidence existed in Ethiopia that was conducted at the hospital level, this study setting difference between hospital and health center might introduce variation service quality and level of care. There is also outcome measurement variation, one month and more missed in this study may increase the incidence. Unlikely, this evidence was lower than findings 21.4/100PYs in Asia–Pacific regions28. This difference may be due to variation of outcome measurement lost to follow-up as used patient not seen in the clinic more than 12 months.

The incidence rate of lost to follow-up is different across time with 3.32/100 person-months at the first month, 5.20/100 person-months at the second month, 3.11/100 person-months at 3 months, and 2.20/100 person-months at 6 months follow-up after ART treatment initiation. Although the incidence rate in the first-year follow-up (27.41/100 PYs) is high, it shows a slight decline over the first-six years follow-up with 13.87/100 PYs at 2nd year, 9.82/100 PYs at 3rd year, 8.45 PYs at 4th year, 6.04 PYs at 5th year, and 4.18 PYs 6th year. Despite this, the incidence was increased to 7.3/100 PY at the end of 9th-year follow-up. This finding is consistent with previous findings from Tigray, Southern, and Oromia regions in Ethiopia, and Nigeria21,36,37,38. However, this finding lies in disagreement with a South African study15. The patients who stayed long periods on ART have had improved adherence, relief from drug-related side effects, less likelihood of opportunistic infections, progressively improved ART service quality in the facility, and establishing lost to follow-up tracing modalities by adherence supporters and volunteer networks in the community. This might have a direct effect on patient retention on antiretroviral therapy.

The proportion of lost to follow-up is 40.8% in this study which is higher than previous reports which ranged from 2.87 to 25.3% in various regions of Ethiopia2,22,24,27,34,39,40,41,42, 12.4% in Malawi20, 16.4% in South Africa19, 28% in Nigeria21, 24.6% in Sub-Saharan Africa10, and 243.9% in South-Eastern Nigeria Hospitals30. The possible explanation for this disparity may be settings (in this study, i.e. laboratory service, counseling, and clinical case management), the difference in health center compared to most of the previous findings in hospitals, and poor health-seeking behavior, used measurement difference lost to follow-up, socioeconomic, and socio-demographic differences across facilities and countries impacting on lost to follow-up.

ART drug adherence was a statistically significant predictor of lost to follow-up; patients who had poor ART drug adherence were 3 times more at risk of lost to follow-up compared to good ART drug adherence. This is consistent with the study conducted in Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Oromia region, Jima Specialized Hospital Ethiopia, sub-Saharan African, low and middle-income countries meta and systematic analysis, and Nigeria2,4,21,23,25,32. The possible reasons may be due to HIV patients’ hopelessness on treatment, conflicts with religious concerns, demanding traditional healers, lack of social support, fear of stigma and discrimination, drug side effects, and other socio-economic reasons that cause them to miss their medication.

Similarly, last functional status is statistically significant to lost to follow-up: Patients who had ambulatory and lower last functional status were 2.74 times more at risk to lost to follow-up compared to those with working as last functional status. This study finding is consistent with the studies conducted in Kimbata and Hadiya zone, Oromia region, Jinka hospital Ethiopia, and (sub-Saharan Africa, low and middle-income countries) meta and systematic analysis,2,8,10,22,25,32,43. The possible reason for this finding might be ambulatory and less functional status patients were more likely to experience lost to follow-up due to inability to work or decrease productivity in all aspects of social, economic, and financial influences. They also need help and close supervision to ensure adherence to ART, which might have been a high probability to the drug side effects; hence, collectively these experiences may affect retention on ART care.

Moreover, those who did not take INH prophylaxis therapy were found to be 1.65 times more at risk to lost to follow-up compared to counterparts who did take INH therapy. This finding supported previous findings in Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Pawi General Hospital, Wukro Hospital, public hospitals Binishangul Gumuz, and in southern Ethiopia24,25,34,37,40,41. INH prophylaxis therapy recommended by the national treatment guideline may direct effect on decrease lost to follow-up by strengthening retention of HIV patients on ART service since INH prophylaxis therapy controls one of the most common life-threatening co-morbidity and mortality threats (i.e., tuberculosis co-infection) among HIV infected people3. This existing intervention to improve the health of the patient may encourage patients’ retention on ART care.

In conclusion, the time to lost half of the patients was 77 months, and the incidence of lost to follow-up was high. Poor drug adherence, ambulatory & less last functional status, and not taken INH prophylaxis were predictors for lost to follow-up among adult HIV/AIDS patients. The government gives special attention to the quality of HIV care at the health center level. There is an imperative to design new initiatives to reduce lost follow-up at the national level including improving ART accessibility modalities, early reminder strategies through tell-medicine, and expansion of laboratory services at preferred sites.

Methods

Study design and setting

An institution-based retrospective follow-up study was conducted from January 1, 2008 to December 30, 2017. Data were collected from February 28–March 16, 2018. The study was conducted at the Bichena Health center. It is found 355 km (km) from Bahir Dar city of Amhara National Regional State and 265 km from Addis Ababa capital of Ethiopia. The health center started ART services in 2008, serving a 51,653 catchment population. It was the first high load ART site health center in the East Gojjam Zone, having 2,770 patients registered for ART service, among those 2,655 (95.8%) were adult ART users, which constituted the source population in this study.

Participants

The study population was all HIV-infected adults (> 15 years) who enrolled at Bichena Health Center ART clinic from January 1, 2008–December 30, 2017. Adult HIV-infected patients who had at least-one ART follow-up visit were eligible to include. Those patients who had unknown ART initiation date, absence of baseline data record or follow-up form in the patient chart and transfer in with incomplete baseline data were excluded in this study (Fig. 4).

Definition of variables

-

Lost to follow-up: A patient who has not received ART medication for more than 1 month of their last missed drug collection appointment8,13,14,15.

-

Disclosure: If anyone knows the status of the patient/child at the workplace, school, family, and other community members44.

-

Adherence: The level of adherence was assessed at every time the patient comes to clinical visit as good (> 95%) missed ≤ 2 doses in 30 doses or ≤ 3 doses of 60 doses, fair (85–94%) missed 3–5 doses in 30 doses or 4–8 doses of 60 doses, and poor (< 85%) missed ≥ 6 doses in 30 doses or ≥ 9 doses of 60 doses44.

-

Risk behavior: If the patient has one or more of the following risks (i.e. having multiple sexual partners, practicing unsafe sex, use of tobacco, and alcohol drink) were considered as a risk behavior44.

-

Functional status: The functional status was assessed continuously to every clinical visit as (working = able to perform usual work in or out of the house, harvest, go to school, ambulatory = ambulatory but not able to work or able to perform activities of daily living, and bedridden = not able to perform activities of daily living)44.

-

Regimen change: As an event, through the follow-up period was ascertained retrospectively when the patients are recorded as changed their regimen and started other ART drugs45.

-

TB screening: The screening is done at the time of ART initiation and every clinical visit what every the screening is through using x-ray or clinically but not on any anti-TB medication44.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated by a double population formula using Epi Info™ version 7 software considering the following assumptions: level of precision 5%, confidence interval 95%, power 80%, the proportion of unexposed (female gender) 22.87%15, the proportion of exposed (male gender) 28.60%15, hazard ratio 1.51, and nonresponse rate 10%. Hence, a sample size of 559 was computed with the inclusion of a 10% non-response rate. The study participants were selected by computer-generated simple random sampling technique using their medical record numbers.

Data collection procedure and quality assurance

A retrospective record review technique was used to collect the required data. All eligible medical recorded data were taken from the ART intake forms and follow-up charts. The data was collected by two diploma nurses and one public health officer as supervisor. The checklist was adapted from the standard Ministry of Health ART intake forms and follow-up charts. Socio-demographic data, past medical history, drug adherence, and clinical & laboratory results were the components of the checklist. Data quality was maintained starting during designing the checklist, training for data collectors’ ad supervisor, and close supervision held during the entire data collection period.

Data processing and statistical analysis

EpiData version 4.2 Entry client was used for data entry and Stata/SE version 14.0 was used for data cleaning and analysis. Data were checked for completeness and inconsistencies before the analysis. Survival Kaplan Meier estimator was used to show the survival and failure estimate curve. Cox regression analysis was fitted to identify the association between dependent and independent variables. Model fitness was checked by Cox proportion hazard model, log–log plot graphically, and test proportional hazard assumptions by Scheonfeld residual. The goodness of fit was checked by running Cox-Snell residual analysis (Fig. S1). Descriptive analysis; frequency tables, mean, median, range, and graphs were done to describe important variables. All predictors that had a significant association with lost to follow-up in the bivariable Cox regression model with p-value < 0.25 were included in multivariable analysis. Finally, significant predictors at p-value < 0.05 in multivariable Cox regression at 95% CI were declared statistically significant for lost follow-up.

Ethics statement and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Debre Markos University, College of Health Science ethical review committee (#HSC/R/C/S/P/Co/696//11/10). The need of informed consent was waived by the Ethics committee of Debre Markos University. The information given was maintained strictly confidential and used for this study purpose only. All procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Limitations

In this study, about 17 patient charts for those who had not or incomplete baseline data were not included. Since we are used secondary data important predictors like viral load, hemoglobin test, and other clinical factors were not included as they were not properly recorded. Also, the lost follow-up might be affected by length–time bias. Thus, this finding should be considered with these limitations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tigist Bacha BTaAW. Predictors of treatment failure and time to detection and switching in HIV-infected Ethiopian children receiving first-line antiretroviral therapy. BMC Infect. Dis. 12(197), 1–8 (2012).

Megerso, A., Garoma, S., Eticha, T., Workineh, T. & DabaSh, T. M. Predictors of loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment for adult patients in the Oromia region, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS-Res. Palliat. Care 8, 83–92 (2016).

Federal Ministry of Health E. National guidelines for comprehensive HIV prevention, care, and treatment. in Edited by Control HPa. 5th edn. (2017).

DinberuSeyoum, J.-M.D. et al. Risk factors for mortality among adult HIV/AIDS patients following antiretroviral therapy in southwestern Ethiopia: an assessment through survival models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14(296), 1–12 (2017).

UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS data. Vol. 1211. 468. (WHO, 2021).

UNAIDS. Global HIV Statistics, Fact Sheet; World AIDS Day and Epidemiological Estimates. (UNADIS, 2021).

Gesesew, H. A. et al. Discontinuation from antiretroviral therapy: A continuing challenge among adults in HIV care in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12(1), e0169651 (2017).

Kebede, H. K., Mwanri, L., Ward, P. & Gesesew, H. A. Predictors of lost to follow up from antiretroviral therapy among adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 10(1), 1–18 (2021).

Olivier Koole, J. A. D. et al. Reasons for missing antiretroviral therapy: Results from a multi-country study in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. PLoS/ONE Cross Mark. 11(1), 1–15 (2016).

Asiimwe, S. B., Kanyesigye, M., Bwana, B., Okello, S. & Muyindike, W. Predictors of dropout from care among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy at a public sector HIV treatment clinic in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 16(1), 1–10 (2015).

Mberi, M. N. et al. Determinants of loss to follow-up in patients on antiretroviral treatment, South Africa, 2004–2012: A cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15(1), 1–11 (2015).

USAIDS. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS Global-AIDS-Update-2016_. 1–16. (2016).

Tadesse, K. & Fisiha, H. Predictors of loss to follow up of patients enrolled on antiretroviral therapy: A retrospective cohort study. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 5(393), 2 (2014).

UNADIS. Global AIDS monitoring 2021. in Edited by Control HPa. (WHO, 2021).

Kranzer, K. et al. Treatment interruption in a primary care antiretroviral therapy program in South Africa: Cohort analysis of trends and risk factors. Eur. PMC Funders Group 55(3), 1–15 (2011).

Tesfaye Asefa, M. T., Dejene, T. & Dube, L. Determinants of Defaulting from Antiretroviral Therapy Treatment in Nekemte Hospital, Eastern Wollega Zone (Public Health Research, 2013).

Moges, N. A., Olubukola, A., Micheal, O. & Berhane, Y. HIV patients retention and attrition in care and their determinants in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 20(1), 1–24 (2020).

Nicole, L. et al. Loss to follow-up trends in HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral treatment in Asia from 2003 to 2013. J. Acq. Immune Defic. Syndromes 74(5), 555 (2017).

Dalal, R. P. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult patients lost to follow-up at an antiretroviral treatment clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J. Acq. Immune Defic. Syndrome 47(1), 101–107 (2008).

Fetzer, B. C. et al. Predictors for mortality and loss to follow-up among children receiving antiretroviral therapy in Lilongwe, Malawi. Tropical Med. Int. Health 14(8), 862–869 (2009).

Seema Thakore Meloni, C. C. et al. Time-dependent predictors of loss to follow-up in a large HIV treatment cohort in Nigeria. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 10(1033), 3–11 (2014).

Wondimu Ayele, A. M., Desta, A. & Rabito, A. Treatment outcomes and their determinants in HIV patients on anti-retroviral treatment program in selected health facilities of Kembata and Hadiya zones, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 15(826), 1–13 (2015).

Lamb, M. R., Geng, E. & Nash, D. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among ART patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 7(6), 1–12 (2012).

Assemie, M. A., Muchie, K. F. & Ayele, T. A. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow up among HIV-infected adults at Pawi General Hospital, northwest Ethiopia: Competing risk regression model. BMC. Res. Notes 11(1), 1–6 (2018).

Mekonnen, N., Abdulkadir, M., Shumetie, E., Baraki, A. G. & Yenit, M. K. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV infected adults after initiation of first-line antiretroviral therapy at University of Gondar comprehensive specialized Hospital Northwest Ethiopia, 2018: Retrospective follow up study. BMC. Res. Notes 12(1), 1–7 (2019).

Addis Akalu, M. Reasons for defaulting from public ART sites in Addis Ababa. in Requirement for Master's Degree in Addis Ababa Univesity. (Addis Ababa University, 2009).

Fekade, D. et al. Predictors of survival among adult Ethiopian patients in the national ART program at Seven University Teaching Hospitals: A prospective cohort study. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 27(1), 63–71 (2017).

Zhou, J. et al. Loss to follow-up in HIV-infected patients from Asia-Pacific region: results from TAHOD. AIDS Res. Treat. (2012).

Ahonkhai, A. A. et al. Not all are lost: Interrupted laboratory monitoring, early death, and loss to follow-up (LTFU) in a large South African treatment program. PLoS ONE 7(3), e32993 (2012).

Eguzo, K., Lawal, A., Umezurike, C. & Eseigbe, C. Predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV-infected patients in a rural South-Eastern Nigeria Hospital: A 5-year retrospective cohort study. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 5(6), 373–378 (2015).

Berheto, T. M., Haile, D. B. & Mohammed, S. Predictors of loss to follow-up in patients living with HIV/AIDS after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 6(9), 453 (2014).

Frijters, E. M. et al. Risk factors for loss to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy programs in low-income and middle-income countries. AIDIS 34(9), 1261–1288 (2020).

Megerso, A. et al. Predictors of loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment for adult patients in the Oromia region, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) 8, 83 (2016).

Teshale, A. B., Tsegaye, A. T. & Wolde, H. F. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow up among adult HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy in University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital: A competing risk regression modeling. PLoS ONE 15(1), e0227473 (2020).

UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Data. Vol. 27. 6–30. (WHO, 2017).

Bucciardini, R. et al. Predictors of attrition from care at 2 years in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected adults in Tigray, Ethiopia. BMJ Glob. Health 2(3), e000325 (2017).

Dessu, S., Mesele, M., Habte, A. & Dawit, Z. Time until loss to follow-up, incidence, and predictors among adults taking ART at public hospitals in Southern Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) 13, 205 (2021).

Abebe Megerso, S. G. Comparison of survival in adult antiretroviral treatment naïve patients treated in primary health care centers versus those treated in hospitals: Retrospective cohort study; Oromia region, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16(581), 1–7 (2016).

Teklu, A. M., Abraha, M., Belayhun, B. & Gudina, E. K. Exploratory Analysis of Time from HIV Diagnosis to ART Start, Factors and effect on survival: A longitudinal follow up study at seven teaching hospitals in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 27(1), 116 (2017).

Dessalegn, M., Tsadik, M. & Lemma, H. Predictors of lost to follow up to antiretroviral therapy in the primary public hospital of Wukro, Tigray, Ethiopia: A case-control study. J. AIDS HIV Res. 7(1), 1–9 (2015).

Degavi, G. Influence of lost to follow up from antiretroviral therapy among retroviral infected patients at tuberculosis centers in public hospitals of Benishangul-Gumuz, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) 13, 315 (2021).

StenWilhelmson, A. R., Balcha, T. T., Jarso, G. & Bjorkman, P. Retention in care among HIV-positive patients initiating second-line antiretroviral therapy: A retrospective study from an Ethiopian public hospital clinic. Glob. Health Action 9(29943), 1–8 (2016).

Tachbele, E. & Ameni, G. Survival and predictors of mortality among human immunodeficiency virus patients on anti-retroviral treatment at Jinka Hospital, South Omo, Ethiopia: a six years retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol. Health 38, 1 (2016).

World Health Organization. Patient monitoring guidelines for HIV care and antiretroviral therapy (ART). in Edited by Control Hpa. (WHO, 2006).

Anlay, D. Z., Alemayehu, Z. A. & Dachew, B. A. Rate of initial highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen change and its predictors among adult HIV patients at University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A retrospective follow up study. AIDS Res. Ther. 13(1), 1–8 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Debre Markos University College of health science for providing ethical clearance, data collectors, supervisors, and Bichena health center staff for their support to retrieve the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T.T. contributed idea conception. A.T.T., M.T., W.W., H.T., N.M.A., P.P., and Y.T. developed a design of methodology. A.T.T., M.T., W.W., D.H., and N.M.A. contributed to data entry analysis and data interpretation. M.T., W.W., H.T., D.H., and Y.T. conducted data supervision and validation. A.T.T., M.T., W.W., H.T., and P.P. review and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Telayneh, A.T., Tesfa, M., Woyraw, W. et al. Time to lost to follow-up and its predictors among adult patients receiving antiretroviral therapy retrospective follow-up study Amhara Northwest Ethiopia. Sci Rep 12, 2916 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07049-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07049-y

- Springer Nature Limited