Abstract

Perceived stress among university students is a prevalent health issue directly correlated with poor academic performance, poor sleep quality, hopelessness, compromised physical and mental health, high risk of substance abuse, and suicidal ideation. Tamarkoz, a Sufi meditation, may reduce the impact of stressors to prevent illness among students. Tamarkoz is the art of self-knowledge through concentration and meditation. It is a method of concentration that can be applied to any task. The method is said to discipline the mind, body, and emotions to avoid unintended distractions. Therefore, it can be used in daily life activities, such as studying, eating, driving, de-stressing or in Sufism, seeking self-knowledge. This study was an 18-week quasi-experimental design with pre-intervention, post-intervention and follow-up assessments in the experimental group, a wait-list control, and a third group that utilized the campus health center’s stress management resources. Participants, university students, had no prior exposure to Tamarkoz, and there were no statistically significant differences among groups on baseline measurements. Using a generalized linear mixed model, significant increases in positive emotions and daily spiritual experiences, and reductions in perceived stress and heart rate were found in the experimental group compared to the other two groups. Tamarkoz seems to show some advantages over the usual stress management resources offered by a student health center.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol Registration Date: (03/04/2018); ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03489148.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perceived stress is a prevalent health concern1 and a neglected global public health issue which has significant negative influence on students’ quality of life2 as it is directly correlated with drop-out3, poor sleep quality4, somatic pain5, hopelessness6, compromised mental and physical health2,7, high risk of substance abuse8, depression9 and suicidal ideation6. Perceived stress is psychological and is induced when a situation or stimulus is assessed as threatening, irrespective of the actual threat value1. Students' stress stems from a variety of pressures including social, financial, personal, and academic challenges10,11. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants such as Adderall, Ritalin, and Vyvanse are common as they attempt to enhance their academic performance12.

Perceived stress is directly correlated with depression- the number of college students diagnosed with depression is increasing and the prevalence of anxiety is high13. Demands for counseling services are increasing14,15, but campuses have limited resources to meet these needs14. It is therefore pragmatic to examine alternative methods for stress management16 and provide students with opportunities to develop skills for reducing the physiological and psychological effects of academic stress13,17.

The physiological response to stressors, allostasis, is the body's attempt to maintain homeostasis by releasing glucocorticoids, epinephrine, and other mediators18. Over time, this allostatic load takes a toll on the body, but things can be done to help mitigate the negative effects of the stress response and to minimize over-reactivity18. Recovery takes place when the stress systems are no longer activated (i.e., relaxation) and this recovery is vital to maintaining physical and mental health, and well-being18,19. A relaxation response can protect against stress-related conditions, and activities such as deep breathing, prayer, and meditation evoke this response at the level of the central nervous system20,21,22.

The central nervous system regulates cardiac and respiratory rhythms, which are functionally related23. Respiration can modulate heart rate which, in turn, influences the sympathetic and parasympathetic response of autonomic nervous24. The phenomenon known as cardiorespiratory synchronization is an interaction between the respiratory system and the human heart25. Research shows that meditation enhances cardiorespiratory synchronization24,26 compared to spontaneous breathing and normal relaxation25,27, and strong synchronization indicates a healthier physiological state25,27.

Cortical activity can also affect cardiorespiratory synchronization. For example, an emotional or cognitive task may arouse sympathetic activity and change breathing rhythm which then increases heart rate28. In contrast, meditation and mind–body interventions with slow breathing can prompt changes in brain activity which work to inhibit sympathetic and limbic responses, and promote the parasympathetic function24. During a prominent parasympathetic activity, there is an increase in alpha waves and functional connectivity in the brain24. The higher levels of cardiovascular synchronization present during meditation lead to hyperpolarization and inhibition of cortical neurons. This results in a homeostatic modulation of the autonomic nervous system and brain activity24. As such, the effects of meditation on homeostasis in the body are more substantial than relaxation alone. Meditation, although relaxing, is a process that inhibits irrelevant thought to selectively focus on a specific target29. The alpha activity measured from EEG during this meditative resting state may be considered thalamocortical and cortical oscillations which have been associated with higher brain functioning and performance29.

There are many different types of meditation such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), Transcendental Meditation (TM), and the Tamarkoz method of meditation. The Tamarkoz method is defined as the art of self-knowledge through concentration and meditation30. It is unique to M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi, the School of Islamic Sufism. The practice of Tamarkoz includes heart-focused meditation, movement balancing meditation, a state of deep relaxation, concentration and visualization, mind relaxation exercises and deep breathing techniques30.

The mind relaxation exercises coupled with deep breathing in the Tamarkoz method are said to control the practitioner’s habitual interfering thought patterns, control emotional reactivity, consciously slow down brain waves, and prepare the practitioner physically and mentally for concentration31. During the state of deep relaxation, the participant releases muscular and nervous tension and dissipates mental and physical fatigue32. As cellular energetic resources are renewed, the participant becomes open to connecting with a deeper dimension of one’s being32. Visualization or imagery in the Tamarkoz method serves to replace negative thought patterns with positive healing images that could be based on the participant’s past experiences33. All five senses are used during this exercise which also provides neurological and sensory training for the participant to develop laser focus on a single point33. The visualization exercises stimulate hope, creativity, motivation and vitality33.

There is substantial evidence in scientific literature that individual techniques similar to those used in Tamarkoz, including deep breathing17, guided visualization34, and slow physical movement35 have physiological effects resulting in improved health outcomes. Benefits such as increase in multiple facets of mindfulness, which have important mental and behavioral health implications associated with improved mood and reductions in perceived stress, appear greater with meditative movements than sitting meditation36. MBSR has been shown to significantly decrease perceived stress37, distractive ruminative thoughts and behaviors2,22, depression and anxiety2, and significantly increase positive moods22, self-compassion, and hope37. TM has been shown to significantly improve distress, anxiety, and depression38. The benefits are not limited to well-being, but also extend to improve cognitive functioning (e.g., knowledge retention in college students) by facilitating mindful control over one’s attention, and directing sustained attention on a chosen thought or object39,40,41. While the positive health effects of some forms of meditation are well-established in scientific research, to our knowledge there has been little published research in scientific peer-reviewed journals on the Tamarkoz method.

The various meditation practices have similar effects on balancing the nervous system and inducing a relaxation response that ultimately promotes health with stress reduction16,17,19,36. However, they differ in the manner of practice, the traditions from which they stem, the ways they are learned, their physiological effects, and the purpose for the practices (see Table 1). For example, MBSR, and TM are secularized, whereas Tamarkoz is a spiritual practice. Research has demonstrated significant positive correlations between spirituality and health outcomes, and studies show spirituality may improve health and reduce stress42.

Spirituality has been incorporated into treatment interventions with mindfulness-based therapies which focus on awareness of an experience and its consequent effects43. Although MBSR is a secularized behavioral medicine program, it has roots in Buddhist meditative spiritual practice44. Participation in a MBSR program has been shown to significantly increase both mindfulness and spirituality scores and also to reduce psychological distress44. Just as a spiritual aspect is sometimes integrated with mindfulness-based interventions, research has also demonstrated that mindfulness-based interventions can enhance spiritualty44. This increase in spirituality is especially pronounced with interventions that have a heavy focus on spirituality, such as with some substance-use recovery programs45.

Practitioners of spiritual meditation have demonstrated better coping, increased pain tolerance, better mental health, more positive moods and less anxiety than secular meditation practitioners46. Spiritual meditation has also been shown to reduce stress reactivity through feelings of spiritual connection, feelings of peacefulness and calmness, and increased self-efficacy46.

Although elements of spirituality (e.g., spiritual well-being, spiritual dimension, spiritual awareness) are found in research literature, it is argued that the essence of spirituality cannot be adequately defined with language47. Nevertheless, some researchers emphasize the importance of detailed definitions for research purposes despite the majority’s conclusion that there is not a unified definition of spirituality42,47. Some define spirituality as intrinsic beliefs and personal values that guide daily living47, others define it as the core of one’s existence and suggest that it gives significance to people's lives, and some consider spirituality and religiosity to be interchangeable42.

Health scientists see spirituality as distinct from religiosity47. Religion may be defined from a health science perspective as a multidimensional construct and an organized system of beliefs, practices and symbols designed to foster closeness to God or the sacred, whereas spirituality has been defined as the connection to that which is sacred48. These definitions overlap, but the distinction between religion as adherence to particular practices and beliefs may sometimes conflict with forms of spirituality49. Research shows that both religiosity and spirituality can help people deal with adversity, illnesses, and other stressful situations48. However, although religiosity has sometimes been shown to be an effective coping mechanism, the type of religious coping is a critical component in psychological outcomes49. Positive religious coping is correlated with positive outcomes while negative religious coping is correlated with negative outcomes42.

A belief in God may be another factor that some use to differentiate between being spiritual and religious. Atheists and agnostics do not believe in a God and may be doubtful of organized religion50 but may be spiritual or experience associated feelings such as connectedness, harmony, love, humility, emotional stability, compassion, and more51. Although there are many different definitions of spirituality52, it is commonly viewed as being developed through prayer and meditation53. Religion may provide guidelines through which spirituality may be developed. For example, it may be viewed as a training system through which individuals can learn to discover divine representations in themselves53.

In the discipline of Islamic Sufism, from which the Tamarkoz method of meditation derives, the goal is to achieve knowledge of one’s unlimited true self called the “I,” which is said to be located in each person’s physical heart53 and which is referred to as the “Source of Life,” in the heart by the great Sufi Master Professor Sadegh Angha54. Thus, meditation and concentration on the heart is important in Sufi teachings and practices, as it is said to be the gateway to the spiritual dimension of a human being53. The spiritual dimension is one’s connection to all existence which is the discovery of the unlimited true self. This is said to occur when you “Gather all your energies and concentrate them on the source of life in your heart for your findings to become imperishable, so that you will live in balance and tranquility and know eternity”54. This form of concentration in the heart enables one’s connection to all existence and the ability to find tranquility and balance. Tamarkoz, taught by instructors who have been approved by Sufi Master Professor Nader Angha, is one approach to facilitating this sense of tranquility and balance utilized by the M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi, School of Islamic Sufism.

Individuals do not have to be followers of the Sufi faith to participate in the practice. Tamarkoz is said to create a state of equilibrium, balance and harmony for an individual53. Harmony is said to be achieved when the entire being is present and not focused on thoughts, emotions, the senses, or any other factors external to oneself53. Thoughts, emotions and senses are not considered to be part of the true self in Sufism, because these are all subject to change and anything that changes is not considered to be truth53. Furthermore, the senses are limited in their perceptions.

For example a typical human eye is sensitive to wavelengths between 380 and 750 nm on the electromagnetic spectrum55. A Tamarkoz practitioner is said to meditate within the heart to become sensitive to electromagnetic waves that do not reach the threshold of action potentials56. Rather, M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi teaches that the heart is capable of receiving these subtle electromagnetic waves which are then transmitted to the brain for processing and amplification so that they can reach threshold for action potentials, provided that the brain dismisses other potentially interfering stimuli56. This is one of the many ways that Tamarkoz is different from mindfulness or other forms of meditation. The result of such a connection between the heart and brain is the discovery of “I,” which is equated with achieving oneness with existence. The components of the practice are used to quiet the mind so one’s concentration and focus is directed on the heart.

Christian literature also refers to the heart. For example, Prayer of the Heart (PH) is the central contemplative practice of the Eastern Christian traditions Apophthegmata and Hesychasm57. Some consider the concept of the heart in this prayer to be metaphorical and symbolic, however phenomenological analysts explain how Prayer of the Heart are actual embodied psychosomatic experiences57,58. The PH experience is described as an egological awareness of the body-self in the chest area associated with sensations, emotions, feelings, and verbal thoughts57, which is different from Tamarkoz meditation. According to Sufi teachings, the human being is not limited to the body and one’s true self or “I” is not a psychological system developed in the mind. In Sufism, the body is considered a vehicle or a tool by which one can develop one’s inner connection to the unlimited within the human heart. The brain is considered part of the body and thus, self-identity is not achieved from the mind or consciousness. Judgments, perceptions and emotions are subject to change and so they are also not considered part of the stable, true self. The practices of Sufism, such as Tamarkoz, are methods of connecting to one’s true self within the human heart which is said to be boundless and not limited to the senses, mind or the physical body. As taught in Sufism, this true self called the “I,” is stable, never subject to change and resilient. No matter any changes or challenges that occur in one’s external environment including the body, one always remains stable, balanced, and resilient because one is deeply rooted within the being and connected to a stable true self53.

Along with meditation in the heart, another component of Tamarkoz is Movazeneh, which is slow movement and balancing meditation. It gathers the practitioner’s attention and focus to a single point that expands to the entire body through concentrated movements, which allows one to experience the present moment59. Table 2 provides a comparison between Movazeneh and other movement meditations.

Movazeneh is said to direct the practitioner’s mind from a scattered to a collective state as the movement and postures stimulate the relevant nerve fibers of a specific body area which generates action potentials to the brain to increase related interferences, and disciplines the practitioner to avoid unintended abortive interferences and thereby induce higher levels of concentration56.

Movazeneh is also said to balance and activate the electromagnetic system in the human body59, whereas the practices of Tai-Chi, Qigong, and yoga focus on encouraging the flow of energy called qi or chi in traditional Chinese medicine, and Prana in Hindu philosophy. Each of these different practices focuses on highly organized energy systems in the human body. Non-Western traditional medicine and Eastern medicine developed healing practices based on observations of the entire body system of the living human being and relationships to specific symptoms60,61, in part because dissection of cadavers was prohibited61. They discovered highly organized energy systems that maintain overall wellbeing, but the energy systems cannot be directly observable by scientific measurements61.

The energy system of Eastern traditional medicine is known to have channels throughout the body through which energy flows. For example, according to traditional Chinese acupuncture theory, meridians are channels in the body through which qi flows62,63. Qi is a vital life energy in traditional Chinese medicine63, Tai-Chi, and Qigong. There are believed to be twelve63 or forteen62 main meridian channels longitudinally distributed on the body and named for major organs presumed to be affected by each meridian (e.g., heart, lung, gall bladder), in addition to smaller channels that branch from the main channels and reach deeper inside the body62. According to traditional Chinese medicine, illness or disease occurs when there is disruption in the flow of qi also known as chi; thus practices such as Tai-Chi, Qigong, and acupressure are devised to restore the flow. Chi functions according to the same concept as Kundalini energy or prana. The ancient practice of classical yoga also serves to improve the flow of prana or Kundalini to promote health and wellbeing. According to Indian philosophy, prana is the universal life force, and Kundalini is a dormant form of this universal energy that is said to be in the base of the spine64. Through yoga movements and breathing, the Kundalini energy becomes “awakened” and moves upwards in the spine through channels called chakras to the crown of the head64,66,67 enabling spiritual awareness64.

According to ancient Indian Ayurvedic medicine, there are seven main chakras in the human body which are considered to be energy vortices that increase in energy level along the spine and head67. Many of these chakras have the same name as the locations of the electromagnetic centers in the human body, but these chakras are located along the spine at the level of the organs, whereas the electromagnetic centers are located in the named organ.

According to the teachings of M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi there are thirteen important electromagnetic centers in the human body with the main center located in the heart53,68, specifically in the Crista Terminalis53. The other important centers are located in the cerebral cortex, crown of the head (anterior fontanel and gray layer), third eye, third ventricle in the brain, brain stem, throat, thymus, three other nodes in the heart, solar plexus and the coccyx66. Based on the teachings, spirituality is experienced with activation and balance of these electromagnetic centers in the human body53.

Although science has not yet clearly defined these electromagnetic centers in the human body, the electrical properties of the heart can be measured with the electrocardiograph, the activities of the brain can be measured with electroencephalogram, and the electromyogram can be used to measure electrical activity in muscles. Additionally, scientists in the field of biomagnetism have made discoveries regarding measurement of the magnetic field of the human body and its specific organs, including the heart and brain65,69,70. Although the electrical and magnetic properties of the body are measurable, the electromagnetic centers have yet to be understood by science53.

As there is a focus on activating, balancing, and harmonizing the electromagnetic energy centers in the body during the Tamarkoz method, deep breathing exercises during the practice are said to fuel these energy centers. The oxygen provided in deep breathing along with concentration and the visualization of a particular anatomy, increases energy production and the desired electromagnetic waves in the area56. Among other benefits, deep breathing techniques control the depth, rhythm and the duration of the breath while also increasing respiratory capacity for maximal oxygenation, and stimulation of the immune system71. Furthermore, it is said the breathing techniques help to cleanse the cells and nerve channels for advanced control of subtle energies71. The explanation of how deep breathing cleanses the immune system and the central nervous system as well as how it enhances receptivity and amplification of electromagnetic waves is written with meticulous detail in the scientific book entitled “Expansion and Contraction within Being (Dahm),” by His Holiness Professor Nader Angha, Sufi Master of M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi, School of Islamic Sufism.

Although there may not yet be a device that measures the level of activation for electromagnetic centers in the body, there are other measurable, physiological benefits to movement meditation and balancing72. Physical movement increases blood circulation which increases oxygen to tissues and enhances lymph flow in lymphatic vessels which improves immune function73. Other benefits of movement meditation include improved balance, flexibility, stability and strength72.

One of the places Tamarkoz is taught is at the University of California, Berkeley through the student-run democratic education program. The course is enrolled to capacity every semester with diverse students from different majors and has a waitlist of well over 100 people. The course provides a rich opportunity for studying this spiritually-based meditation as a potential health-promotion and disease-prevention tool. This was the aim of the present study, with the specific hypotheses that participants in the Tamarkoz class would have (a) reduced perceived stress, (b) increased positive emotions, (c) more frequent daily spiritual experiences, (d) decreased blood pressure, and (e) decreased heart rate compared to two control groups.

Methods

Design

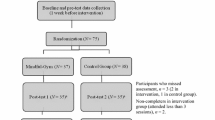

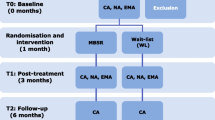

This study was a three-group quasi-experiment. The three groups were: (a) a Tamarkoz group, (b) a stress management (standard practice) control group, and (c) a Tamarkoz waitlist control group. Participants self-selected into the Tamarkoz group or the stress management group. All groups were measured at three points in time: (a) at baseline near the beginning of the fall semester, (b) approximately 12 weeks after baseline, and (c) approximately 18 weeks after baseline.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were that participants be University of California, Berkeley students between the ages of 18–30 years; not work third shifts; and not have diabetes, post-traumatic stress disorder, liver disease, autoimmune diseases, or severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., severe depression that resists treatment or impacts ability to function; schizophrenia). As can be seen in Table 3, the samples for all three groups were diverse in ethnicity, religious beliefs, socioeconomic status, level of education, and field of study. Table 4 shows baseline continuous demographic variables such as age, and the six outcome variables: perceived stress, positive emotions, daily spiritual experiences, heart rate, diastolic and systolic blood pressure.

Recruitment

Recruitment began during the first week of the fall semester. Flyers were posted throughout the Berkley campus, and provided to the campus student health center for posting at their stress management resource center. The intervention group was recruited from the Tamarkoz class for only first-time Tamarkoz students. Participants were not provided extra credit for the study, and the instructor was not informed which of her students had enrolled in the study.

The Waitlist control group was recruited from the waitlist of the Tamarkoz class and other students who wanted to enroll into the class. Participants in the waitlist group did not utilize stress management resources at the campus’ student health center for the duration of the study and received priority registration for Tamarkoz for the following semester. Students were informed that they would not be dropped from the study if they decide at any time to use the stress management resources. Each self-report questionnaire asked students whether they utilized the campus health center’s stress management resources. The participants in the Stress Management Resources (standard practice control) group utilized the campus health center's stress management resources on an as-needed basis. Their resources included access to health coaching, individual counseling and psychological services, group counseling, online educational information about self-care for stress management, pet hugs, and use of a massage chair. Baseline was completed prior to the intervention group's first exposure to Tamarkoz class. Figure 1 provides information on the number of participants and the dates for each data collection wave.

Compensation

Once students contacted the researcher and self-reported meeting the eligibility criteria, they were provided an appointment to meet with the researcher on campus in a designated room where all participants gave their informed consent and had blood pressure and heart rate measurements taken. To the extent possible, participants of each group were met with separate appointments to reduce chances that group members would communicate with each other about the study. Participants were compensated up to $10 in Amazon gift cards for each of the following items if they were complete and provided on time: (a) blood pressure/heart rate measurements, and (b) the online self-report survey.

Measures and covariates

The self-report questionnaires, blood pressure, and heart rate were assessed at baseline, end of course (12 weeks) and 18 weeks. The questionnaires were emailed as an online survey through Qualtrics to participants for their participation at every data collection time point. In order to confidentially track each participant over time, each person was associated with a specific participant code.

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured with the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS, α = 0.88 in our data)74. The scale measures the degree to which one perceives situations in one’s life as stressful, such as “In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life?” The scale includes six negatively worded items that represent stress and four positively stated items that represent confidence and control. Responses range from 0 = never to 4 = very often. Items were summed across the scale providing a range of 0 to 40. Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of perceived stress.

Dispositional positive emotions

Positive emotions were measured with the Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale (DPES)75. This scale is a 38-item (α = 0.94) self-report questionnaire. An example of an item from the scale is, “I see beauty all around me.” The responses range from 1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree with possible scores ranging of 38 to 266. Items were summed across the scale and then reversed so that higher scores indicate more positive emotions.

Daily spiritual experiences

Spirituality levels were measured with the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES)76. This scale consists of 16-items (α = 0.95) that assess an individual’s perception of the transcendent, divine, or holy in their daily life. The constructs of the scale represent common processes in religiousness and spirituality within daily life. An example of an item from the scale is, “I find strength in my religion or spirituality.” Reponses range from 1 = many times a day to 6 = never with scores ranging from 16 to 96. The 16th item on the scale is reversed coded and then the items were summed. The total score was reversed so that higher scores indicate more daily spiritual experiences.

Blood pressure and heart rate

Blood pressure and heart rate measurements were taken with an Omron 10 Plus Series Upper Arm Blood Pressure Monitor, which is a validated instrument approved and recommended by dabl Educational Trust for accuracy. Three measurements were taken with a thirty second pause between, then these three were averaged.

Control variables

Gender, age, ethnicity, religious preference, and self-reported exercise minutes per week at baseline were controlled in this analysis. Because there were fewer than ten people in many of the religious preferences, people were dichotomized into Christians, other religion or atheists/agonistics. The Tamarkoz group had a writing space on their survey where they had the option to share about their experience with Tamarkoz.

Experimental intervention

The Tamarkoz group participants had one lecture and one meditation practice per week. All Tamarkoz study participants were taught by the same instructor. The lecture portion of the class provides context for the Tamarkoz practice and as stated on the course syllabus provides “Understanding of the principles, basic beliefs, and goals of Sufism, and the role Tamarkoz plays in achieving the aim of practical Sufism, which is self-knowledge.” According to the course syllabus, the class is based on the teachings of the Sufi Masters of the Maktab Tarighat Oveyssi (M.T.O.) Shahmaghsoudi, School of Islamic Sufism with particular focus on the teachings of Professor Angha. The goal of Sufism is self-knowledge; thus, the teachings presented in class elaborate on the elements of this goal. The Tamarkoz practice sessions include the following elements: Light stretches to release tension from the physical body. Then mind relaxation, and deep breathing exercises, followed by Movazeneh, and then deep relaxation, visualization, and then heart concentration, which focuses on the heartbeat. For more details, please see http://mtoshahmaghsoudi.org.

Human subjects

Loma Linda University’s Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all aspects of the research study (LLU-2016-5150225). All aspects of the study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including informed consent. All students were eligible to register for the Tamarkoz course until capacity was met and all students were eligible to use the self-care stress-management resources at the campus student health center.

Data analysis

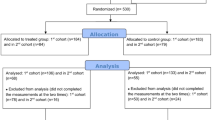

There was only one independent variable: whether the participant was in the Tamarkoz group, the stress management control group, or the Tamarkoz waitlist control group. Six outcome variables were tested: perceived stress, positive emotions, daily spiritual experiences, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate. Participants with missing information on perceived stress, dispositional positive emotions, and daily spiritual experiences were excluded from the analyses resulting in a baseline sample size of 103 participants. Data for blood pressure and heart rate measurements were entered into SPSS using double entry to ensure accuracy. SPSS-23 was used for all statistical analyses. Baseline differences on categorical variables were tested using the χ2 goodness-of-fit test and on continuous variables using one-way ANOVA. For analyses that involved examining participants across time, the generalized linear mixed model was used. Linear mixed models, when used for analysis of repeated measures data, have advantages over the standard linear models approach; in particular, they enable us to deal effectively with both within- and between-person variability. This is because, among other things, they do not require the assumption of independence of observations over time77 and differences between groups can be modeled as random effects. Each of the six dependent variables had three effects tested: (a) wave, which tested whether there were consistent differences in a variable across time regardless of group; (b) group, which tested whether the average value for each group differed regardless of time; and (c) the group by wave interaction which tested whether the pattern of change over time differed from one group to another. For testing these three effects on the six outcome variables we used five variables as statistical controls: gender, age, ethnicity, religious preference, and baseline level of exercise. While none of these variables were significantly different at baseline, we decided that it would make sense to control for basic demographics and one health habit, exercise, that could have significant effects on stress management. The intent was to increase our power by controlling for extraneous variation.

Results

Baseline differences in outcome variables and comparison with scale norms

Table 4 shows that at baseline there were no statistically significant differences in means among groups in perceived stress, dispositional positive emotions, daily spiritual experiences, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate. Cohen's normative group for perceived stress had the following parameters: M = 16.78, SD = 6.86, 95% CI: [15.88, 17.68], n = 223. The results for perceived stress measurements for our groups were the following: Tamarkoz group: (t(250) = 1.38, p = 0.168); Stress Management group: (t(265) = 1.78, p = 0.077); Waitlist group: (t(251) = 1.63, p = 0.105). While our groups have higher means than the normative table, the differences are not statistically significant.

Differences between reported positive emotions in the normative table, whose participants were also students from a large West Coast University, and the groups in this study were statistically significant with the same age group and the following parameters: M = 4.98, SD = 0.71, 95% CI: [4.85, 5.11], n = 119, compared to baseline of the Tamarkoz group: (t(146) = 4.58, p < 0.001); the Stress Management group: (t(161) = 6.25, p < 0.001); and the Waitlist group: (t(146) = 4.66, p < 0.001).

The normative table for daily spiritual experiences was derived from the General Social Survey78, which was based on responses from the 16-item Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale taken in 2004 by people who were between the age group of 18–30 years old. These values were M = 47.87, SD = 18.00, 95% CI [45.73, 50.01], n = 272. At baseline, the normative numbers are different than our groups, and had statistically significantly higher daily spiritual experiences than the Tamarkoz group: (t(299) = 3.53, p = 0.001); the Stress Management group: (t(19.40) = 4.21, p < 0.001); and the Waitlist group: (t(13.00) = 5.76, p < 0.001).

Group differences in outcome variables

Table 5 shows results from the repeated measures analysis for all dependent variables while Table 6 shows the means and 95% confidence intervals for these same variables for each group at each of the three-time points. The means are adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity/race, religious preference, and exercise minutes per week. Figure 2 shows the patterns of these changes over time. There was significant difference in the use of stress management resources between the Stress Management group and the Tamarkoz group, such that the Stress Management group utilized them more.

Perceived stress

As shown in Table 5, the hypothesis that perceived stress would be lower for the Tamarkoz group was supported, with a significant group-by-wave interaction. Figure 2 demonstrates that the Tamarkoz group showed a steady decrease in perceived stress over time, whereas the other two groups increased before dropping back toward baseline. At the second wave the sequential-Sidak, paired-comparison test showed that the Tamarkoz group’s stress was lower than both control groups, but the difference was significant only for the Waitlist group (t(273) = 2.98, p = 0.009). At the third wave, however, (6-week posttest) the Tamarkoz group was significantly different from both the Waitlist group (t(273) = 3.79, p = 0.001) and the Stress Management group (t(273) = 2.50, p = 0.026).

Dispositional positive emotions

This study also supports the hypothesis that Tamarkoz increases positive emotions in university students compared to a group utilizing standard stress management resources and a waitlist control group. Table 5 indicates a significant group-by-wave interaction. Figure 2 and Table 6 show that dispositional positive emotions increase following the intervention in the Tamarkoz group but stay about the same in the two control groups. The sequential-Sidak, paired-comparison tests demonstrate that at the second wave, positive emotions for the Tamarkoz group are significantly higher than the Stress Management group (t(273) = 3.30, p = 0.003) and the Waitlist group (t(273) = 2.89, p = 0.008).

Daily spiritual experiences

This study supports the hypothesis that Tamarkoz increases daily spiritual experiences. Over half of the participants in the Tamarkoz group were atheists, agnostics, or had no religious preference yet increases in daily spiritual experiences were still observed, demonstrating that the technique is not limited to those who self-designate as religious or who declare a religious affiliation. Table 5 demonstrates a significant group-by-wave interaction in daily spiritual experiences. The pattern denoted in Fig. 2 illustrates the increase in daily spiritual experiences for the Tamarkoz group relative to the other two groups in wave 2 and 3. Sequential-Sidak, paired-comparison tests at the second wave demonstrate that the Tamarkoz group has statistically significant higher daily spiritual experiences than the Waitlist group (t(273) = 3.60, p = 0.001), and marginally significant compared with the Stress Management group (t(273) = 2.24, p = 0.051). At the third wave, the Tamarkoz group had higher daily spiritual experiences than the Stress Management group (t(273) = 2.34, p = 0.059) and the Waitlist group (t(273) = 2.26, p = 0.059), but these differences are only marginally significant.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate

Figure 3 illustrates that the Tamarkoz group had lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure at the second wave and the third wave compared to the Stress Management group and the Waitlist group, however the differences were not statistically significant.

Self-report of reduced perceived stress in the Tamarkoz group was supported by significantly reduced heart rate. Sequential-Sidak, paired-comparison tests indicate a significant group-by-wave interaction for heart rate such that the Tamarkoz group had significantly lower heart rate than the Stress Management group (t(231) = 4.09, p < 0.001) and the Waitlist group (t(231) = 2.82, p = 0.011) at the second measurement wave. Figure 3 also shows that the Tamarkoz group had reduced heart rate during the second wave and continued to have lower heart rate than the two other groups during the third wave.

Discussion

University students' stress, depression and anxiety are neglected public health issues which have significantly negative impacts on students’ quality of life, academic performance, and prospective occupational success. Health-related habits formed during the period of university and college life may be difficult to change later on13. Research studies on health and wellness emphasize the need for multidimensional, whole person wellness programs that include physical, emotional, behavioral, and spiritual elements46.

Studies show that college and university students with high levels of distress tend to use more substances such as alcohol and illicit drugs and this creates a real public health challenge for American college campuses8,79. Challenges can be exacerbated and made more difficult for college counselors to address because of the complex ways in which these factors are related to personal characteristics and contemporary culture15. Given the rather consistently stressful college environment, the diversity-related challenges, and the financial costs associated with more traditional medical treatments, it is important to find innovative approaches for addressing the stress-related health issues. There is a good deal of evidence for the benefits of meditation on various aspects of health. This study adds to the literature by demonstrating that during the most stressful time of the semester, compared to two control groups, the participants in the Tamarkoz group experienced significantly more positive emotions, more daily spiritual experiences, reduced perceptions of stress, and reduced heart rate, which suggests the body’s effective regulation of cardiovascular reactivity.

The outcomes of this study are consistent with the idea that positive emotions may effectively counteract negative emotions and thereby improve psychological resiliency and speed recovery from cardiovascular events induced by negative emotions80. The broaden-and-build theory80 of positive emotions posits that they prepare the individual to better deal with stressful events and, hence, lessen perceived stress and enhance emotional well-being.

Additionally, our results showed a significant relationship between positive emotions and daily spiritual experiences. It has been suggested that spiritual people tend to experience more positive emotions, such as feelings of fulfillment, which may provide an inner strength that protects against negative feelings of anxiety or despair81.

Increase in spirituality and practices such as meditation and prayer elicit relaxing physiological effects on the body that improves health outcomes44,52,82 and may thereby decrease stress. Spirituality can positively influence psychological well-being, as it can buffer against adverse stressors of daily life and moderates the effects of stress even without religious affiliation81. A fair number of participants (approximately 57%) in the Tamarkoz group were atheists, or agnostics. The results provide important implications for health promotion and wellness programs in that Tamarkoz increases daily spiritual experiences regardless of religious affiliation.

Tamarkoz techniques provides students with tools to manage stress, regulate their emotions and increase spiritual experiential details in daily life. It can be practiced at any time, and in any location preferred by the participant. It does not require a gym, or a special meditation location, and does not require hours of commitment in a day. This is especially important in that students are taught techniques to use on their own, which may lead fewer students needing to utilize support services.

Limitations of the study included that the sample sizes of the groups were not large, and thus it is possible that there was insufficient power to pick up the association in the posttests for all three groups in some variables. Furthermore, the Stress Management group (as a comparison group), was not required to engage in a specific number of hours of exposure to a stress management resource. However, one purpose of this study was to determine whether the stress management resources available to use independently was sufficient. Additionally, because there were no statistically significant differences on demographics, perceived stress, positive emotions, or daily spiritual experiences at baseline for the three groups, we did not control for previous meditation practice. It may be, however, that those with prior experience with other meditation modalities might be able to transition into a meditative practice more quickly. Therefore, future studies with larger sample sizes might benefit from including this as a control.

Strengths of this study were use of validated scales and objective, physiological measures with clinically validated monitors, and comparison groups, which allowed to control for a variety of variables. The Stress Management group may control for possible placebo effects as those utilizing the stress management program would believe, as would the Tamarkoz group, that they were receiving something to help with stress, yet the Tamarkoz group was more positively affected. The Waitlist Control group was recruited from the waitlist of the Tamarkoz group, which served as an appropriate comparison group as participants had the same interests in Tamarkoz.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the health promotion benefits of incorporating a specific type of meditation class as a curriculum for university students. Based on the study results, it seems that just providing resources for stress management on campus is not enough, but rather providing a course that incorporates spirituality and teaches skills as well as the opportunity to practice and develop these skills, will not only reduce perceived stress, but also increase positive emotions and daily spiritual experiences. In a national survey of United States college students, over 80% indicated interest in spirituality, however inner development of students, such as spirituality, emotional maturity and self-understanding has been neglected at higher education institutions83. Thus, universities may need to offer courses on learning techniques that will counter stress, while fostering spirituality—techniques such as those offered in Tamarkoz training— particularly since it seems to show some advantage over the usual stress management resources offered by a student health center. It is interesting that in the two control groups of this study, the stress went up at the time of finals, which suggests there are in fact problems on college campuses that need to be dealt with in some way. One of these ways may be a course such as Tamarkoz.

A future study could require participants in a stress management group to utilize stress management resources for the same duration as the Tamarkoz group. Another study could explore whether the decrease stress in university students who participate in Tamarkoz would potentially decrease symptoms of anxiety or depression. A suggestion for the next study is to incorporate random assignment to conditions.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the American Educational Research Association Data Repository, https://doi.org/10.3886/E137281V1.

References

Largo-Wight, E., Peterson, P. M. & Chen, W. W. Perceived problem solving, stress, and health among college students. Am. J. Health Behav. 29, 360–370. https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.29.4.8 (2005).

Mahmoud, J. S. R., Staten, R. T., Hall, L. A. & Lennie, T. A. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 33, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.632708 (2012).

Devos, C. et al. Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: A matter of sense, progress and distress. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 32, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-016-0290-0 (2016).

Lund, H. G., Reider, B. D., Whiting, A. B. & Prichard, J. R. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J. Adolesc. Health 46, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016 (2010).

Kennedy, C., Kassab, O., Gilkey, D., Linnel, S. & Morris, D. Psychosocial factors and low back pain among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 57, 191–196 (2008).

Dixon, W. A., Rumford, K. G., Heppner, P. P. & Lips, B. J. Use of different sources of stress to predict hopelessness and suicide ideation in a college population. J. Couns. Psychol. 39, 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.39.3.342 (1992).

O’Leary, A. Stress, emotion, and human immune function. Psychol. Bull. 108, 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.363 (1990).

Broman, C. L. Stress, race and substance use in college. Coll. Stud. J. 39, 340–352 (2005).

Sawatzky, R. G. et al. Stress and depression in students: The mediating role of stress management self-efficacy. Nurs. Res. 61, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e31823b1440 (2012).

Adams, D. R., Meyers, S. A. & Beidas, R. S. The relationship between financial strain, perceived stress, psychological symptoms, and academic and social integration in undergraduate students. J. Am. Coll. Health 64, 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2016.1154559 (2016).

Oman, D., Hedberg, J. & Thoresen, C. E. Passage meditation reduces perceived stress in health professionals: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74, 714–719. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.714 (2006).

Herman, L. et al. The use of prescription stimulants to enhance academic performance among college students in health care programs. J. Phys. Assist. Educ. 22, 15–22 (2011).

Stewart-Brown, S. et al. The health of students in institutes of higher education: An important and neglected public health problem?. J. Public Health Med. 22, 492 (2000).

Aselton, P. Sources of stress and coping in american college students who have been diagnosed with depression. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 25, 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2012.00341.x (2012).

Kitzrow, M. A. The mental health needs of today’s college students: Challenges and recommendations. J. Stud. Affairs Res. Pract. 41, 165–179 (2003).

Burns, J. L., Lee, R. M. & Brown, L. J. The effect of meditation on self-reported measures of stress, anxiety, depression, and perfectionism in a college population. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 25, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2011.556947 (2011).

Paul, G., Elam, B. & Verhulst, S. J. A longitudinal study of students’ perceptions of using deep breathing meditation to reduce testing stresses. Teach. Learn. Med. 19, 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330701366754 (2007).

McEwen, B. S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 840, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x (1998).

van Hooff, M. L. M. & Baas, M. Recovering by means of meditation: The role of recovery experiences and intrinsic motivation. Appl. Psychol. 62, 185–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00481.x (2013).

Benson, H. The Relaxation Response (Morrow, 1975).

Gregg, J. The physiology of mind–body interactions: The stress response and the relaxation response. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 7, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/107555301753393841 (2001).

Jain, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Ann. Behav. Med. 33, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2 (2007).

Jacobs, G. The physiology of mind–body interactions: The stress response and the relaxation response. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 7, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/107555301753393841 (2001).

Jerath, R., Barnes, V. & Braun, M. Mind-body response and neurophysiological changes during stress and meditation: Central role of homeostasis. J. Bio Reg. Homeos AG 28, 545–554 (2014).

Wu, S.-D. & Lo, P.-C. Cardiorespiratory phase synchronization during normal rest and inward-attention meditation. Int. J. Cardiol. 141, 325–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.137 (2010).

Chang, C.-H. & Lo, P.-C. Effects of long-term Dharma-Chan meditation on cardiorespiratory synchronization and heart rate variability behavior. Rejuvenation Res. 16, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2012.1363 (2013).

Cysarz, D. & Bussing, A. Cardiorespiratory synchronization during Zen meditation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-005-1379-3 (2005).

Zhang, J., Yu, X. & Xie, D. Effects of mental tasks on the cardiorespiratory synchronization. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 170, 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2009.11.003 (2010).

Kim, D., Kang, S. W., Lee, K.-M., Kim, J. & Whang, M.-C. Dynamic correlations between heart and brain rhythm during Autogenic meditation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00414 (2013).

M.T.O.®. How Does Tamarkoz® Work? http://tamarkoz.org/tamarkoz/how-does-tamarkoz-work/ (2016).

Shahmaghsoudi, M. Tamarkoz Technique: Mind Relaxation. http://tamarkoz.org/tamarkoz/mind-relaxation-2/ (2020).

Shahmaghsoudi, M. Tamarkoz Technique: Deep Relaxation, http://tamarkoz.org/deep-relaxation/ (2020).

Shahmaghsoudi, M. Tamarkoz Technique: Imagery. http://tamarkoz.org/tamarkoz/visualization/ (2020).

Margolin, I., Pierce, J. & Wiley, A. Wellness through a creative lens: Mediation and visualization. J. Relig. Spiritual. Soc. Work 30, 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2011.587385 (2011).

Yeh, G. Y. et al. Effects of tai chi mind–body movement therapy on functional status and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Med. 117, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.016 (2004).

Caldwell, K., Harrison, M., Adams, M., Quin, R. H. & Greeson, J. Developing mindfulness in college students through movement-based courses: Effects on self-regulatory self-efficacy, mood, stress, and sleep quality. J. Am. Coll. Health 58, 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480903540481 (2010).

Shapiro, S. L., Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R. & Cordova, M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 12, 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.2.164 (2005).

Nidich, S. I. et al. A randomized controlled trial on effects of the Transcendental Meditation program on blood pressure, psychological distress, and coping in young adults. Am. J. Hypertens. 22, 1326–1331. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2009.184 (2009).

Ramsburg, J. & Youmans, R. Meditation in the higher-education classroom: Meditation training improves student knowledge retention during lectures. Mindfulness 5, 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0199-5 (2014).

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D. & Davidson, R. J. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005 (2008).

Travis, F. & Shear, J. Focused attention, open monitoring and automatic self-transcending: Categories to organize meditations from Vedic, Buddhist and Chinese traditions. Conscious. Cogn. 19, 1110–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.01.007 (2010).

Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E. & Larson, D. B. Handbook of Religion and Health: Harold G. Koenig, Michael E. McCullough, David B. Larson (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Kick, K. A. Trauma, spirituality, and mindfulness: Finding hope. Soc. Work. Christ. 43, 97–108 (2016).

Carmody, J., Reed, G., Kristeller, J. & Merriam, P. Mindfulness, spirituality, and health-related symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 64, 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.015 (2008).

Shorey, R. C., Gawrysiak, M. J., Anderson, S. & Stuart, G. L. Dispositional mindfulness, spirituality, and substance use in predicting depressive symptoms in a treatment-seeking sample. J. Clin. Psychol. 71, 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22139 (2015).

Wachholtz, A. B. & Pargament, K. I. Is spirituality a critical ingredient of meditation? Comparing the effects of spiritual meditation, secular meditation, and relaxation on spiritual, psychological, cardiac, and pain outcomes. J. Behav. Med. 28, 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9008-5 (2005).

Nelms, L. W., Hutchins, E., Hutchins, D. & Pursley, R. J. Spirituality and the health of college students. J. Relig. Health 46, 249–265. https://doi.org/10.2307/27513007 (2007).

Koenig, H. G. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 33. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730 (2012).

Seybold, K. S. & Hill, P. C. The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 10, 21–24 (2001).

Hwang, K., Hammer, J. & Cragun, R. Extending religion-health research to secular minorities: Issues and concerns. J. Relig. Health 50, 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-009-9296-0 (2011).

Caldwell-Harris, C. L., Wilson, A. L., Lotempio, E. & Beit-Hallahmi, B. Exploring the atheist personality: Well-being, awe, and magical thinking in atheists, Buddhists, and Christians. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 14, 659–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.509847 (2011).

Miller, W. R. & Thoresen, C. E. Spirituality, religion, and health. An emerging research field. Am. Psychol. 58, 24–35 (2003).

Angha, N. Theory “I”: The Unlimited Vision…of Leadership (M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi Printing & Publication Center, 2002).

Angha, P. S. Message from the Soul 35th edn. (MTO Shahmaghsoudi Publications, 1986).

Evers, C., Starr, C. & Starr, L. Biology Today and Tomorrow with Physiology 2nd edn. (Thomson Brooks/Cole, 2007).

Angha, S. A. N. Expansion and Contraction Within Being (Dahm) (Shahmaghsoudi Printing and Publication Center, 2000).

Louchakova-Schwartz, O. Theophanis the Monk and Monoimus the Arab in a phenomenological-cognitive perspective. Open Theol. 1, 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2016-0005 (2016).

Louchakova-Schwartz, O. Qualia of God: Phenomenological materiality in introspection, with a reference to Advaita Vedanta. Open Theol. 3, 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2017-0021 (2017).

M.T.O.®. Definition of Movazeneh®. http://tamarkoz.org/tamarkoz/movazaneh/ (2016).

Chin, R. The Energy Within: The Science Behind Eastern Healing Techniques (Da Capo Lifelong Books, 1995).

Collins, C. Yoga: Intuition, preventive medicine, and treatment. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 27, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02623.x (1998).

Langevin, H. M. & Yandow, J. A. Relationship of acupuncture points and meridians to connective tissue planes. Anat. Rec. 269, 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.10185 (2002).

Zhang, W.-B., Wang, G.-J. & Fuxe, K. Classic and modern meridian studies: A review of low hydraulic resistance channels along meridians and their relevance for therapeutic effects in traditional Chinese medicine. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/410979 (2015).

Woollacott, M. H., Kason, Y. & Park, R. D. Investigation of the phenomenology, physiology and impact of spiritually transformative experiences kundalini awakening. Explore 2020, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2020.07.005 (2020).

Cohen, D. Magnetic fields around the torso: production by electrical activity of the heart. Science 157, 652–654 (1967).

Angha, M. S. M. S. The Hidden Angles of Life Vol. 60 (M.T.O. Publications, 2012).

Maxwell, R. W. The physiological foundation of yoga chakra expression. J. Sci. Study Relig. 44, 807–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2009.01035.x (2009).

Angha, P. S. Hamase Hayat. The Epic of Life Vol. 160 (M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi® Printing Center, 1981).

Cohen, D. in Biomagnetism; An Interdisciplinary Approach (eds Williamson S. J., Romani, G. L. & Modena I. Kaufman, L.) 327–339 (Springer, 1983).

Williamson, S. J. & Kaufman, L. Biomagnetism. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 22, 129–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-8853(81)90078-0 (1981).

Shahmaghsoudi, M. Tamarkoz Technique: Breathing Exercises. http://tamarkoz.org/tamarkoz/breathing/ (2020).

Zheng, G. et al. Effectiveness of Tai Chi on physical and psychological health of college students: Results of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 10, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132605 (2015).

Benschop, R. et al. Relationships between cardiovascular and immunological changes in an experimental stress model. Psychol. Med. 25, 323–327 (1995).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 (1983).

Shiota, M., Dacher, K. & Oliver, J. Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. J. Posit. Psychol. 1, 61–71 (2006).

Underwood, L. G. The daily spiritual experience scale: Overview and results. Religions 2, 29–50 (2011).

Shek, D. T. L. & Ma, C. M. S. Longitudinal data analyses using linear mixed models in SPSS: Concepts, procedures and illustrations. Sci. World J. 11, 42–76. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2011.2 (2011).

Smith, T. W., Hout, M. & Marsden, P. V. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor] (2013).

Hagga, D. et al. Effects of the transcendental meditation program on substance use among university students. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2011, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/537101 (2011).

Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 300–319 (2001).

Kim, Y. & Seidlitz, L. Spirituality moderates the effect of stress on emotional and physical adjustment. Pers. Individ. Differ. 32, 1377 (2002).

Chang, B.-H., Casey, A., Dusek, J. A. & Benson, H. Relaxation response and spirituality: Pathways to improve psychological outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation. J. Psychosom. Res. 69, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.007 (2010).

Higher Education Research Institute. The Spiritual Life of College Students: A National Study of College Students’ Search for Meaning and Purpose (Higher Education Research Institute, 2007).

Louchakova-Schwartz, O. in The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Well-Being 29 (2020).

Bai, Z. et al. The effects of qigong for adults with chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Chin. 43, 1525–1539. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0192415X15500871 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B., J.W.L., and L.R.M. conceptualized the study; N.B. collected the data; N.B. and J.W.L. conducted analyses; N.B. drafted the manuscript; N.B., J.W.L. and L.R.M. revised the manuscript; all authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahadorani, N., Lee, J.W. & Martin, L.R. Implications of Tamarkoz on stress, emotion, spirituality and heart rate. Sci Rep 11, 14142 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93470-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93470-8

- Springer Nature Limited