Abstract

Persons living with diabetes (PLWD) with newly diagnosed tuberculosis are at greater risk of poor treatment outcomes. Identifying and prioritizing high-risk subgroups of PLWD and tuberculosis for tuberculosis programs to target has been rarely performed. We investigated risk factors for poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes among PLWD and developed a predictive risk score for tuberculosis control prioritization. Among PLWD diagnosed with tuberculosis, demographic, clinical, and tuberculosis treatment outcome data were collected. Poor treatment outcomes included treatment failure, death, default, and transfer. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was used to analyze risk factors of poor treatment outcomes. Risk scores were derived based on regression coefficients to classify participants at low-, intermediate-, and high-risk of poor treatment outcomes. Among 335 PLWD newly diagnosed with tuberculosis, 109 were cured and 172 completed treatment. Multivariable logistic regression found that risk factors of poor treatment outcomes included bacteriologically-positivity, low body mass index, no physical activity, and pulmonary cavitation. Rates of poor treatment outcomes in low- (0–2), intermediate- (3–4), and high-risk (5–8) groups were 4.2%, 10.5%, and 55.4% (Ptrend < 0.0001), respectively. The risk score accurately discriminated poor and successful treatment outcomes (C-statistic, 0.85, 95% CI 0.78–0.91). We derived a simple predictive risk score that accurately distinguished those at high- and low-risk of treatment failure. This score provides a potentially useful tool for tuberculosis control programs in settings with a double burden of both tuberculosis and diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis has been identified as one of the top 10 causes of death globally1. Persons with an impaired immune system, such as those living with diabetes, are at a higher risk of developing tuberculosis and having poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes once diagnosed2,3,4,5. Globally, the burden of diabetes is increasing at alarming rates—in 2019, there were 463 million (9.3%) persons living with diabetes (PLWD) which is predicted to rise to 10.2% (578 million) by 2030 and 10.9% (700 million) by 20456. Currently, 80% of adults with diabetes reside in low- and middle-income countries where tuberculosis is also endemic7,8. An estimated 11% of all global tuberculosis deaths are attributable to diabetes9.

PLWD have an increased risk of poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes including failure and death during treatment and subsequent relapse2,3,4,5,10,11. Characteristics that put PLWD at-risk for treatment failure or death have been heterogeneous and how tuberculosis control programs can effectively and efficiently target PLWD newly diagnosed with tuberculosis for enhanced monitoring and investigation is not well elucidated3. Understanding subgroups of tuberculosis patients with diagnosed diabetes at highest risk of treatment failure is critical for tuberculosis control programs to prioritize enhanced management and resources for these patients.

We aimed to investigate tuberculosis treatment outcomes among a cohort of PLWD newly diagnosed with tuberculosis in Jiangsu province, China. We developed a risk classification model that may be clinically useful to identify and prioritize PLWD newly diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Methods

Study design and participants

The National Basic Public Health Service Project has been conducted since 2009 in China and provides basic public health services to the general public free of charge, focusing on children, pregnant women, elderly, and patients with chronic diseases. This service includes the management of PLWD age 35 and above with physical examinations performed twice a year. Participants of this study were based in four cities in Jiangsu Province: Danyang, Rugao, Jiangyin and Nanjing city, China. All diagnosed diabetes patients in care participated in the diabetes physical examination from January to December 2017. Physical examinations for type 2 diabetes include fasting blood glucose test, height, weight, waist circumference, body temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure. We collected physical examination and anti-tuberculosis treatment outcome data among PLWD tuberculosis patients from the Chinese Tuberculosis Information Management System12,13. To further assess tuberculosis among PLWD, we used unique identification numbers from each patient to crossmatch the screening database of the Diabetes Physical Examination System and the Tuberculosis Management Information System. After linkage by the unique identification numbers, age, first and last name, date of birth, sex, and address were compared for confirmation. We then summarized the information of the matched patients. The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study definitions

All diagnosed PLWD were screened for tuberculosis through a clinical symptom screen, chest X-rays, and bacteriological testing. Tuberculosis diagnosis was made based on definitions provided by the World Health Organization14. New tuberculosis cases were defined as tuberculosis patients whose medical records indicated that the patient had denied having any prior anti-tuberculosis treatment or any history of more than 30 days of anti-tuberculosis treatment. Previously treated tuberculosis cases were defined as persons with documented evidence of prior treatment in the case report or surveillance database. A 3HRZE/6HR treatment regimen was used for diabetes-tuberculosis patients based on recommendations by the World Health Organization and the National Tuberculosis Control Program, China14,15. Treatment outcomes were defined as designated by World Health Organization guidelines16,17. Cured was defined as a pulmonary tuberculosis patient with culture-confirmed tuberculosis at the beginning of treatment who was culture-negative in month 5 or 6 during anti-tuberculosis treatment. Cultures were obtained at two, five, and the end of anti-tuberculosis treatment; ‘treatment failure’ was recorded if cultures or smears were positive at the 5th and 6th month of treatment. Death comprised of any patient who deceased for any reason during the course of tuberculosis treatment. Poor treatment outcomes only included treatment failure, death and treatment interruption due to adverse reaction. Glycemic control among PLWD was defined as poor if a participant’s first fasting plasma glucose test was above either 7.2 (definition 1) or 10 mmol/L (definition 2), based on recommendations from the American Diabetes Association18 and prior studies19,20.

Statistical analysis

Treatment outcome data and risk factors were analyzed and compared in the patient cohort. Descriptive analyses were performed to characterize distributions of available variables in our study population. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze risk factors of tuberculosis treatment outcomes for tuberculosis patients with diabetes. We then derived risk scores through a multi-pronged approach. Briefly, univariable logistic regression was used to determine the relationship of each independent variable for poor treatment outcomes. In multivariable logistic regression model building, we selected variables with clinical significance and all predictors with a P value < 0.1 in the univariable model21. Sex and age were included in the multivariable logistic model regardless of P value. We then identified variables with statistically significant independent predictive value (P < 0.1) in the multivariable logistic regression model using Hosmer–Lemeshow model tests. We checked for linearity in the logit of continuous variables and for significant interaction terms22. We also assessed goodness of fit and stability during model building. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and used to describe the impact of related factors on treatment outcomes of diagnosed diabetes patients with tuberculosis.

We then derived risk scores based on multivariable logistic regression models. We followed previously published recommendations for developing predictive risk scores23,24. Briefly, we computed how far each subcategory of a risk factor was from the base category for each predictor variable in the multivariable analysis and derived a constant for the points system relating to the number of regression units corresponding to 1 point. The risk score model is derived to compute the required ∑βX for a given risk factor profile. The risk estimate was then determined from a reference table which provides risk estimates for each point total. While the function itself can accommodate distinct values for the risk factors (e.g., age, sex, body mass index) on a continuous scale. The points system is organized around categories in order to mirror clinically meaningful risk factor states24.

We assigned a point score based on a transformation of corresponding β regression coefficients. The subsequent score was rounded to the nearest integer for clinical and programmatic practicality. We then calculated a risk score for each individual patient. The study population was grouped into three risk stratifications (low-, intermediate-, and high-risk) based on the probability of poor treatment outcomes in each group. Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses for the risk score was performed to assess the performance of the score. We internally validated the risk score using tenfold cross-validation. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 23.0).

Ethics statement

This project was approved by Institutional Review Board of Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

All co-authors consent to this submission.

Results

Demographic characteristics

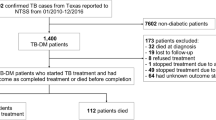

The National Basic Public Health Service Diabetes Patients Physical Examination Project were conducted in four cities (Danyang, Rugao, Jiangyin, and Nanjing). A total of 335 PLWD and tuberculosis were included in this study (Fig. 1). The mean age was 64.9 (Standard Deviation, ± 11.9) years old and 234 (69.9%) were male. Most patients did not drink (79.1%) or smoke (71.6%). Chest radiographs and sputum smear were performed in all patients, 28.5% (96/337) patients had lung cavities, 57.3% (193/335) were smear-negative, and 14.9% (N = 50) were previously treated tuberculosis patients. Among smear-positive patients, the sputum smear conversion rate was 77.1% (N = 111) after intensive treatment (Table 1). Of 335 patients, 109 were cured and 172 completed treatment. In all, 54 tuberculosis cases (16.11%) had poor treatment outcomes. Of these, 14 died (25.9%), 37 (68.5%) failed treatment, and 3 (5.6%) had treatment interruption due to adverse events (Fig. 1).

Risk factors for poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes

In univariable logistic regression analyses, men were more likely to experience poor treatment outcomes (OR, 2.8, 95% CI 1.3–6.3). Poor treatment outcomes were also more likely when patients were bacteriologically-positive (OR, 6.4, 95% CI 3.0–13.6), had pulmonary cavitation (OR, 8.2, 95% CI 4.3–15.6), had a previous tuberculosis episode (OR, 3.1, 95% CI 1.5–6.1), no exercise (OR, 6.7, 95% CI: 2.4–19.1), and patients with a body mass index < 18.5 (OR, 4.4, 95% CI 1.6–12.0 compared to participants with a body mass index between 18.5 and 23.9) (Table 2).

In a multivariable logistic regression analysis, similar characteristics were risk factors for poor treatment outcomes. These included a low body mass index < 18.5 (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR], 6.7, 95% CI 1.8–24.3), no exercise (AOR, 6.0, 95% CI 1.9–18.5), bacteriological positivity (AOR, 3.4, 95% CI 1.4–7.9), and pulmonary cavitation (AOR, 6.1, 95% CI 2.8–13.0) (Table 2).

Development of predictive risk score

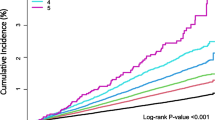

When assigning a point score, patients were assigned 1 point if they had a previous tuberculosis episode or were bacteriologically positive. Patients with lung cavitation, a body mass index < 18.5, or that did not do any physical activity were given a total of 2 points (Supplementary Table 1). The score ranged from 0 to 8 and treatment failure rates increased with higher score (Ptrend < 0.0001). The estimated risk of poor treatment outcomes increased from 0.3% in patients with 0 points to 60.8% among patients with a score of 8 (Supplementary Table 2). After grouping patients into low- (0–2 points), intermediate- (3–4 points), and high-risk (5–8 points) classification groups, most treatment failures (66.7, 36/54) occurred in the high-risk group and 87.0% (48/54) occurred in intermediate- and high-risk groups. Treatment failure rates were 4.2% (95% CI 1.1–7.4), 10.5% (95% CI 4.4–16.1), and 55.4 (95% CI , 43.0–67.8) in low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups, respectively (Ptrend < 0.0001). The absolute difference in probability of treatment failure between high- and low-risk groups was 51.2% in the cohort (Table 3). The risk score discriminated adverse and successful treatment outcomes well (AUC, 0.85, 95% CI 0.78–0.91) (Fig. 2). In an internal tenfold cross-validation, the risk score had strong predictive ability with a C statistic of 0.83 (95% CI 0.74–0.89).

Discussion

PLWD diagnosed with tuberculosis are at high-risk of treatment failure and death2,3,4,25. However, identifying PLWD at highest risk of treatment failure is critical for tuberculosis control programs with a high diabetes prevalence, such as China. Effective and straightforward tools for public health professionals are urgently needed. We found that PLWD and tuberculosis that were bacteriologically positive, with low body mass index (< 18.5), and with low levels of physical activity were more likely to experience poor treatment outcomes. We derived a prognostic score to ranging from 0–8 which predicted well with treatment failure and death and may be useful for programmatic implementation in tuberculosis control programs.

These results suggest that identifying tuberculosis patients at high- and low probability of poor outcome may be feasible using a set of commonly collected patient-level factors. The risk score had a strong degree of accuracy to discriminate between adverse and successful treatment outcomes (C-statistic, 0.85). There may be unmeasured confounding and data quality may be suboptimal. However, our study, which uses routinely collected data by National Basic Public Health Service Diabetes Patients Physical Examination Project and national tuberculosis programs, has an important ‘real-world’ context and may be practically used to PLWD without additional costs. Additional studies with further risk factors may be useful to improve the diagnostic accuracy of this prognostic model.

Patients that did not exercise had an increased risk of poor outcomes in PLWD diagnosed with tuberculosis, suggesting physical activity may significantly reduce risk of adverse outcomes. This may be related to case severity. If hospitalized patients, who are often the most severe, are unable to exercise this may explain this relationship. Low body mass index (< 18.5) also increased the risk of adverse treatment outcomes. This has been shown in previous studies25,26. Persons with a low body mass index or nutritional disequilibrium may alter the host immune response leading to more severe forms of tuberculosis impacting subsequent poor treatment outcomes27.

We found that patients with bacteriologically positive results at baseline were also more likely to experience poor outcomes. In this study, 82% of patients with poor treatment outcomes were bacteriologically positive, of which 39 were sputum smear positive. Our study did not demonstrate an association of alcohol consumption and smoking with poor treatment outcomes. Other determinants of poor treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients include lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption and drug abuse2,28. There are various mechanisms through which smoking may adversely impact tuberculosis treatment outcome, for example through altering immunological host defense mechanisms, impacting lung structure and function, and modifying mechanisms of pathogen clearance28. This lack of association may be attributed to small numbers of self–reported alcohol consumption and smoking, likely an underestimate considering the social, cultural and religious norms that exist in China29. Importantly, we found that glycemic control did not impact tuberculosis treatment outcomes. Prior studies among participants both with and without diabetes found that glycemic control among PLWD was a risk factor for poor treatment outcomes compared to participants without diabetes3,4. However, our study included only PLWD, therefore the reference group is PLWD with poor glycemic control (rather than persons without diabetes), likely explaining a lack of association with poor treatment outcomes in our study.

There are limitations to this study. First, we had substantial missing data on hypoglycemic drugs used by participants limiting our ability to study the effect of diabetes drug use on tuberculosis treatment outcomes. Poor treatment outcomes may be mediated through specific drugs, such as metformin and, due to this, our results may be impacted. However, drug use may be related to glucose control which was measured in our study. Second, although we included a large number of diagnosed diabetes/tuberculosis patients in the province, our sample size was < 400 patients and a larger sample size may have elucidated further risk factors for poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes. The diagnosis of diabetes was not based on blood glucose levels alone; we enrolled subjects who were known to have diabetes to rule out bias associated with transient hyperglycemia attributed to tuberculosis4,30. Lastly, we were not able to externally validate our prognostic model in another setting which is necessary prior to implementation of such a score in a public health program. Because we did not include a validation cohort from outside of China, it is unclear how these results are generalizable to persons with diabetes/tuberculosis in other countries with large dual epidemics.

Conclusions

Our study shows that PLWD with tuberculosis experienced treatment failure more commonly when bacteriologically positive, previous tuberculosis treatment, low body mass index, limited physical activity, or lung cavitation. Integrated models of care with early screening and management for diabetes and tuberculosis should be initiated. The detection of diabetes in tuberculosis patients and linking these persons to care may improve tuberculosis treatment outcomes. Strengthening early diagnosis and identifying tuberculosis patients with diabetes that are at high-risk of poor treatment outcomes is needed in areas with a high burden of both diabetes and tuberculosis.

Data availability

Please contact the first author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- PLWD:

-

Persons living with diabetes

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

References

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. 2020.

Reed, G. W. et al. Impact of diabetes and smoking on mortality in tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 8, e58044 (2013).

Dooley, K. E. & Chaisson, R. E. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: convergence of two epidemics. Lancet. Infect. Dis 9, 737–746 (2009).

Liu, Q. et al. Glycemic trajectories after tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment outcomes of new tuberculosis patients: a prospective study in Eastern China. Am. J. Respirat. Crit. Care Med. 1, 1 (2021).

Lu, P. et al. Predictors of discordant tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube results in Eastern China: a population-based, Cohort Study. . Clin. Infect. Dis. 1, 1 (2020).

Saeedi, P. et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107843 (2019).

Carracher, A. M., Marathe, P. H. & Close, K. L. International diabetes federation 2017. J. Diabet. 1, 1 (2018).

Magee, M. J. & Narayan, K. M. Global confluence of infectious and non-communicable diseases – the case of type 2 diabetes. Prev. Med. 57, 149–151 (2013).

GBD Tuberculosis Collaborators. The global burden of tuberculosis: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. Infect. Dis 18, 261–284 (2018).

Baker, M. A. et al. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med. 9, 81 (2011).

Faurholt-Jepsen, D., Range, N., Praygod, G., Jeremiah, K. & Friis, H. Diabetes is a strong predictor of mortality during tuberculosis treatment: a prospective cohort study among tuberculosis patients from Mwanza, Tanzania. . Trop. Med. Int. Health. 18, 1 (2013).

Liu, Q. et al. Collateral impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on tuberculosis control in Jiangsu Province. China. Clin. Infect. Dis 1, 1 (2020).

Liu, Q. et al. Undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis infection: a population-based, observational study from Eastern China. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 36(3), e3227 (2020).

World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines 2010 4th edn. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2010).

Department of Disease Control and Prevention Moh. Guidelines for the implementation of Chinese tuberculosis control program 2008 ed2009.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Emergency update. WHO/HTM/TB/2008402 Geneva 2008 (WHO, 2008).

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2011 update. WHO/HTM/TB/20116 Geneva: WHO. 2011.

American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019 Jan 1;42(Supplement 1): S61–70.

Lee, P. H. et al. Glycemic control and the risk of tuberculosis: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 13(8), e1002072 (2016).

Martinez, L. et al. Glycemic control and the prevalence of tuberculosis infection: a population-based observational study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65(12), 2060–2068 (2017).

Abdelbary, B. E., Garcia-Viveros, M., Ramirez-Oropesa, H., Rahbar, M. H. & Restrepo, B. I. Predicting treatment failure, death and drug resistance using a computed risk score among newly diagnosed TB patients in Tamaulipas, Mexico. . Epidemiol. Infect. 145, 3020–3034 (2017).

Harrell, F. E., Lee, K. L. & Mark, D. B. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat. Med. 15, 361–387 (1996).

Sullivan, L. M., Massaro, J. M. & D’Agostino, R. B. Sr. Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: the Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat. Med. 23, 1631–1660 (2004).

Sullivan, L. M., Massaro, J. M. Sr. & DAR. ,. Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: the Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat. Med. 23, 1631–1660 (2004).

Mukhtar, F. & Butt, Z. A. Risk of adverse treatment outcomes among new pulmonary TB patients co-infected with diabetes in Pakistan: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 13, e0207148 (2018).

Choi, H. et al. Predictors of pulmonary tuberculosis treatment outcomes in South Korea: a prospective cohort study, 2005–2012. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 360 (2014).

Yen, Y. F. et al. Association of Body Mass Index With Tuberculosis Mortality: A Population-Based Follow-Up Study. Medicine 95, e2300 (2016).

Jee, S. H. et al. Smoking and risk of tuberculosis incidence, mortality, and recurrence in South Korean men and women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 170, 1478–1485 (2009).

Ezard, N. et al. Six rapid assessments of alcohol and other substance use in populations displaced by conflict. Confl. Heal. 5, 1 (2011).

Boillat-Blanco, N. et al. Transient Hyperglycemia in Patients With Tuberculosis in Tanzania: Implications for Diabetes Screening Algorithms. J. Infect. Dis. 213, 1163–1172 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank for all participants and the support from faculties and staffs in The Third People's Hospital of Zhenjiang and Nanjing Public Health Medical Center.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82003516), Medical Scientific Research General Project of Jiangsu Health Commission (M2020020) and Young Science Talents Promotion Project of Jiangsu Science and Technology Association. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L., N.Y., L.M. conceived the study, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; W.L., L.Z., P.L. participated in the study design; H.P., Y.Z., F.L., H.C., T.Z. implemented the field investigation. All authors contributed to the study and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, N., Pan, H., Zeng, Y. et al. A risk score for prediction of poor treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients with diagnosed diabetes mellitus from eastern China. Sci Rep 11, 11219 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90664-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90664-y

- Springer Nature Limited