Abstract

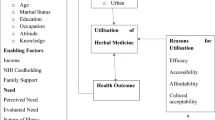

Traditional medicine utilisation during antenatal care has been on the increase in several countries. Therefore, addressing and reinforcing the Sustainable Development Goal of maternal mortality reduction, there is a need to take traditional medicine utilisation during pregnancy into consideration. This paper explores traditional medicine utilisation during antenatal care among women in Bulilima District of Plumtree in Zimbabwe. A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 177 randomly selected women using a semi-structured questionnaire. Fisher's Exact Test, Odds Ratios, and Multiple Logistic Regression were utilised to determine any associations between different demographic characteristics and traditional medicine utilisation patterns using STATA SE Version 13. The prevalence of Traditional Medicine utilisation among pregnant women was estimated to be 28%. Most traditional remedies were used in the third trimester to quicken delivery. The majority of women used holy water and unknown Traditional Medicine during pregnancy. There was a strong association between age and Traditional Medicine utilisation as older women are 13 times more likely to use Traditional Medicine than younger ones. Women use traditional medicine for different purposes during pregnancy, and older women's likelihood to use Traditional Medicine is higher than their counterparts. The traditional system plays an essential role in antenatal care; therefore, there is a need to conduct further studies on the efficacy and safety of utilising Traditional Medicines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal health is generally of global concern, and to ensure safe pregnancies and delivery, several countries have been challenged to provide adequate maternal and child health services as enshrined on the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of reduction in maternal mortality of 7.5% per year between 2016 and 20301,2,3. However, different countries utilise different health systems to achieve these global targets4,5. In Africa (particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa), access to modern health facilities is a challenge due to exorbitant costs associated with it and the health care recipients' economic status6.

Traditional medicine (TM) utilisation has been on the upsurge in several African countries as it plays a vital role during antenatal care7. It could contribute positively or negatively towards the attainment of SDG 3, emphasising reducing the Global Maternity mortality rate to 70 per 100,0003,7,8. The use of traditional medicines in pregnancy management induces and shortens labour is a well-established practice among African countries9,10. Reported reasons for TM utilisation during pregnancy include; promotion of foetal growth, spiritual cleansing, protection against evil influence, to have a male child and assisting childbirth just to mention a few11,12. The route of TM exposure during antenatal care varies; some are ingested, inhaled, or applied as an ointment for different purposes13,14. Determinates such as women's belief, lower cost, and accessibility of TM triggers them to have trust in their effectiveness compared to western medicines15.

In the Zimbabwean context, preference to deliver at home and utilisation of TMs has been influenced by the cost of health care, distance, educational level, and religion16,17,18. Traditional medicines have been utilised since the pre-colonial era, with over 80% of the population still relying on traditional remedies and the Indigenous Knowledge (IK) being passed down to generations19,20. Women prefer birth attendants that understand their spiritual background, and they feel at peace when they perform their cultural activities that are believed to be beyond human capabilities17. In addition, the Zimbabwe Maternal and Perinatal Mortality Study conducted by the Ministry of Health and Child Care in 2007 found that women prefer to go into labour at traditional birth attendants and faith healers' homes21. In Zimbabwe's rural areas, lack of access to western medicines has been an influencing factor for women to use TM. In addition, better modern health facilities with required expertise and equipment are largely centralised in urban setups, making it difficult for rural women to access these services22.

There have been several strategies that have been implemented in rural Zimbabwe including the establishment of Maternal Waiting Homes (MWH) to try and reduce barriers such as cost of transport, distance and prevent maternal complications (just to name a few) to improve access of women to modern maternal health services3,23. However, most women still prefer to utilise TM despite campaigns that discourage women from utilising TM as some have unforeseen adverse reactions24. The majority of users; therefore utilise TM secretly and rarely disclose to the health service providers. In Plumtree, particularly in Bulilima District, the average distance walked by women to the nearest health facility is estimated at between 5 and 10 km, influencing them to consult the traditional system which is readily available in their communities25. Generally, it is suggested that there should be a health facility within a 5 km radius in different communities and women should not walk more than the 5kms in search of maternal services18. Therefore, this study explores traditional medicine utilisation trends during antenatal care among women in Bulilima District of Plumtree in Zimbabwe. This study presents a window of opportunity to determine the TM utilisation patterns that would inform policy makers in coming up with strategies that would strengthen the current existing health systems.

Methods

Study area

Bulilima is one of the seven districts with 22 wards located in Matabeleland South province and is in Region 5, prone to severe drought26. The district has one main referral hospital with sixteen clinics that usually refer pregnant women with complications to a district hospital and has an average household size of 527. Generally, it is estimated that this district is home to 57,68128. The average distance that women walk to the nearest clinic is estimated to be 5–10 km. The study area is illustrated in Fig. 1 which was developed using Quantum Geographic Information System (Credit: QGIS 3.12.2 by the QGIS development team). Although a similar study was conducted in Harare, Zimbabwe which is an urban set up with a different population composition predominantly the Shona tribe, our study was entirely rural-based and in a different region of the country with predominantly Kalanga and Ndebele speaking people relying on different TM as compared to some other regions as the belief systems differ27,29.

Study design

A cross-sectional survey that explored traditional medicine utilisation during antenatal care among women in Bulilima District was conducted. This study design was appropriate as it enabled the exploration of traditional medicine utilisation trends in a single point in time, ensuring cost-effectiveness as this study was not funded30.

Target population

This study targeted all women who delivered from January-December 2019 (to minimise recall bias) in Bulilima District as captured in the health facilities' birth registers. The women who met the inclusion criteria were 586, and there was no age limit.

Sampling

A sample size calculator on EPI INFO Version 7.2.2.6 was used to estimate the minimum sample size required for this study. A confidence level of 95%, Width of Confidence of 5%, and the expected value of attribute applied to the study population of 586 gave an estimated sample size of 185. Random numbers were then generated, and the 185 selected and followed up.

Data collection tools

Pre-testing of a semi-structured questionnaire and data collection was done by the researchers who are all Trained Public Health Specialists between January 2020-February 2020 from women delivered at the clinic or home in Bulilima district but registered at the clinic. The questionnaire was categorised into two sections, that is: the first section delved on socio-demographic characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, parity). The second section comprised questions on the source, different types, reasons, and frequency of TM used. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated to the local language that is "isiNdebele," which is mainly spoken and taught within the district.

Data analysis

Collected data was coded and entered into EpiData 3.1 then further exported to Microsoft Excel 2013. The analysis was done with the aid of STATA version 13; for instance, descriptive statistics were used for women's demographic characteristics. Fisher's Exact, Odds Ratios (OR), and Multiple Logistic Regression (MLR) were used to determine the presence and strength of associations between demographics and TM utilisation.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Permission to carry out the study was sought from relevant authorities that are Provincial Medical Director for Matabeleland South, District Medical Officer for Bulilima and National University of Science and Technology, particularly the Department of Environmental Science and Health. Moreover, the research abides by the Nuremberg code and principles stated in the Helsinki Declaration for the safety of participants involved in the study46. Written consent was obtained from all the respondents who participated in the study. Permission was sought from parents of adolescents who were less than 18 years of age, and there were also required to assent to the study.

Results

Response rate and demographics characteristics of women

Out of the targeted 185 women, 177 responded to a pre-tested questionnaire presenting a response rate of 96%. Some of the women had left their places of residence and could not be obtained. However, a response rate of 96% was considered sufficient by the researchers to make meaningful inferences. The majority of women were having a partner 132 (74.6%), and 139 (78.5%) are Christians, while 110 (62.2%) are unemployed. Also, the results show that only one woman was within the age of 50–54, as indicated in Table 1:

Traditional medicine used during antenatal

The majority of individuals used holy water and an unknown type of traditional medicine, while ten women used only one type of traditional medicine. Fig. 2 and Table 2 show different types of TMs used by women.

Prevalence and safety perception of traditional medicine use

The prevalence of TM use was 50 (28.3%) during pregnancy, and also a more significant number of women use traditional medicines during their third trimester. Table 3 clearly shows prevalence, safety, and other variables of traditional medicines utilisation pattern.

Demographic characteristics and TM use

There was a strong significant association between age and TM utilisation as older women are 13 times more likely to use TM than younger ones. Religion and parity were associated with TM use. On the other hand, marital status, Tribe, Level of education, employment status, and place of delivery was not associated with TM utilisation as shown in Table 1. Age is the only variable significantly associated with the frequency of TM use during pregnancy, as indicated in Table 4.

Discussion

The study found out that most women had a partner, were Christians, and was unemployed. Most researchers that conducted studies in Zimbabwe supports our findings as they revealed that most women attending antenatal care in public institutions are unemployed and are in a relationship31,32. Results indicated that older women's likelihood of using traditional medicine during pregnancy is higher than their younger counterparts. These findings are supported by a study conducted in Taiwan, which indicates that older women are likely to use traditional, complementary medicines than their younger counterparts33. Findings denote that marital status, Tribe, Level of education, employment status, and place of delivery were not significantly associated with traditional medicine utilisation. Studies conducted in Zimbabwe concur with our findings that religion is not related to the use of TMs during pregnancy34.

Our findings indicated that the prevalence of TM use was 28.25%. Most scholars who conducted their studies on maternal health and traditional medicine use in Sub-Saharan countries (Zimbabwe 52%, Nigeria 68%, Mali 80%, South Africa 55–93.6%, Mali 80%, Tanzania 55%) contradicts with our findings as they note that the prevalence ranges from 52 to 80%29,35,36,37,38,39. Even though other scholars contradict our findings, multinational studies conducted in Europe, Australia, South, and North America are aligned with our results as they revealed a prevalence of 28.9% use herbal medicine during pregnancy7.

Women revealed in our study that they use several TMs to induce and shorten labour, these include isikhukhukhu (Snuggle-lea: Pouzolzia hypoleuca Wedd), and inkunzane (Boot protectors/devil thorn; Dicerocaryum species). Other scholars who conducted their studies in Zimbabwe concur with our results as they indicate that Snuggle-lea (Pouzolzia hypoleuca Wedd) was used to induce labour9,11. It is highlighted in this study that the majority of individuals were using holy water and an unknown type of traditional medicine. These results are in line with a study conducted by Mureyi29, that indicated holy water as a common TM used. In addition, scholars have noted that several herbs and their compounds are used during pregnancy are unknown40,41,42.

In Zimbabwe the Traditional health system is recognised and plays an important role in ensuring services are available to those that need them43. In pursuance of SDG (3), there is a need to ensure that utilization of traditional medicines leads to outcomes that do not jeopardise progress towards attaining this specific goal on maternal health44,45.

Limitations

This study cannot be generalised to the entire country since the study population was rural-based and can be affected by recall bias even though women recruited gave birth during January-December 2019. Above all, the research was not funded, and as such, there could have been a need for a substantial cohort to make meaningful inferences. Authors are also involved in a project that intends to explore maternal complications and TM use and find the active ingredient of TM used by women during antenatal care.

Conclusion

Women indeed used traditional medicine for different purposes during pregnancy, and the likelihood of older women to use traditional medicines was higher than in young women. Most dominant traditional remedies were used in the last trimester to quicken delivery by women. TM utilisation plays a significant role in pregnancy; therefore, there is a need that particular attention is paid to it and possibly more research to be conducted to assess its efficacy, safety as it gives a cheaper alternative to women who might not afford to access conventional modern health services.

References

World Health Organization & UNICEF. (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015).

Lawn, J. E., Blencowe, H., Kinney, M. V., Bianchi, F. & Graham, W. J. Evidence to inform the future for maternal and newborn health. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 36, 169–183 (2016).

Koblinsky, M. A. Reducing Maternal Mortality: Learning from Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica and Zimbabwe (The World Bank, Geneva, 2003).

Dunlop, D. W. Alternatives to “modern” health delivery systems in Africa: Public policy issues of traditional health systems. Soc. Sci. Med. 1967(9), 581–586 (1975).

Nunu, W. N., Makhado, L., Mabunda, J. T. & Lebese, R. T. Strategies to facilitate safe sexual practices in adolescents through integrated health systems in selected districts of Zimbabwe: A mixed method study protocol. Reprod. Health 17, 20 (2020).

Doctor, H. V., Nkhana-Salimu, S. & Abdulsalam-Anibilowo, M. Health facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: Successes, challenges, and implications for the 2030 development agenda. BMC Public Health 18, 765 (2018).

Kennedy, D. A., Lupattelli, A., Koren, G. & Nordeng, H. Herbal medicine use in pregnancy: Results of a multinational study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 13, 355 (2013).

Schunder-Tatzber, S. European Information Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (EICCAM) gestartet. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsmedizin/Swiss J. Integr. Med. 22, 90–90 (2010).

Panganai, T. & Shumba, P. The African Pitocin-a midwife’s dilemma: The perception of women on the use of herbs in pregnancy and labour in Zimbabwe, Gweru. Pan Afr. Med. J. 25 (2016).

Dika, H. I., Dismas, M., Iddi, S. & Rumanyika, R. Prevalent use of herbs for reduction of labour duration in Mwanza, Tanzania: Are obstetricians aware? Tanzania J. Health Res. 19 (2017).

Chamisa, J. A. Zimbabwean Ndebele Perspectives on Alternative Modes of Child Birth (University of South Africa, Pretoria, 2013).

Varga, C. A. & Veale, D. Isihlambezo: Utilization patterns and potential health effects of pregnancy-related traditional herbal medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 44, 911–924 (1997).

Rahman, A. A., Sulaiman, S. A., Ahmad, Z., Daud, W. N. W. & Hamid, A. M. Prevalence and pattern of use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in Tumpat district, Kelantan. Malays. J. Med. Sci. MJMS 15, 40 (2008).

Nyeko, R., Tumwesigye, N. M. & Halage, A. A. Prevalence and factors associated with use of herbal medicines during pregnancy among women attending postnatal clinics in Gulu district, Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 296 (2016).

Choguya, N. Z. Traditional birth attendants and policy ambivalence in Zimbabwe. J. Anthropol. 2014 (2014).

Muchabaiwa, L., Mazambani, D., Chigusiwa, L., Bindu, S. & Mudavanhu, V. Determinants of maternal healthcare utilization in Zimbabwe. Int J Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. 5, 145–162 (2012).

Ensor, T. & Cooper, S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 19, 69–79 (2004).

Nunu, W. N., Ndlovu, V., Maviza, A., Moyo, M. & Dube, O. Factors associated with home births in a selected ward in Mberengwa District, Zimbabwe. Midwifery 68, 15–22 (2019).

Mposhi, A., Manyeruke, C. & Hamauswa, S. The importance of patenting traditional medicines in Africa: the case of Zimbabwe. Int. J. Human. Soc. Sci. 3, 236–246 (2013).

Kazembe, T. Traditional medicine in Zimbabwe. Rose + Croix J. 4, 55–72 (2007).

Munjanja, S. P., Nystrom, L., Nyandoro, M. & Magwali, T. Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. Zimba. Matern. Perinat. Mortal. Study 2009 (2007).

Magadi, M. A., Agwanda, A. O. & Obare, F. O. A comparative analysis of the use of maternal health services between teenagers and older mothers in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Soc. Sci. Med. 64, 1311–1325 (2007).

Chandramohan, D., Cutts, F. & Millard, P. The effect of stay in a maternity waiting home on perinatal mortality in rural Zimbabwe. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98, 261 (1995).

Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 4, 177 (2014).

Mudyarabikwa, O. & Mbengwa, A. Distribution of public sector health workers in Zimbabwe: a challenge for equity in health. (EQUINET Discussion paper 34. Harare: EQUINET, 2006).

Dube, E. Environmental challenges posed by veld fires in fragile regions: The case of the Bulilima and Mangwe districts in southern Zimbabwe. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 7 (2015).

David, R. & Dube, A. An assessment of health information management infrastructures for communication in the Matabeleland South region border-line health institutions in Zimbabwe. J. Health Inform. Africa 1 (2013).

Agency, Z. N. S. Zimbabwe Population Census, 2012 (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare, 2012).

Mureyi, D. D., Monera, T. G. & Maponga, C. C. Prevalence and patterns of prenatal use of traditional medicine among women at selected harare clinics: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 164 (2012).

Sedgwick, P. Cross sectional studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ 348 (2014).

Muti, M., Tshimanga, M., Notion, G. T., Bangure, D. & Chonzi, P. Prevalence of pregnancy induced hypertension and pregnancy outcomes among women seeking maternity services in Harare, Zimbabwe. BMC Cardiovasc. Disorders 15, 111 (2015).

Moyo, W. & Mbizvo, M. T. Desire for a future pregnancy among women in Zimbabwe in relation to their self-perceived risk of HIV infection, child mortality, and spontaneous abortion. AIDS Behav. 8, 9–15 (2004).

Yeh, H. Y. et al. Use of traditional Chinese medicine among pregnant women in Taiwan. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 107, 147–150 (2009).

Dimene, L. et al. A cross-sectional study to determine the use of alternative medicines during pregnancy in the district hospitals in Manicaland, Zimbabwe. Afr. Health Sci. 20, 64–72 (2020).

Godlove, M. J. Prevalence of herbal medicine use and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Mbeya Refferal Hospital in 2010, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (2011).

Ngomane, S. & Mulaudzi, F. M. Indigenous beliefs and practices that influence the delayed attendance of antenatal clinics by women in the Bohlabelo district in Limpopo, South Africa. Midwifery 28, 30–38 (2012).

Tamuno, I. Omole-Ohonsi, A., and Fadare J.(2010). Use of herbal medicine among pregnant women attending a tertiary hospital in northern Nigeria. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 15.

Fakeye, T. O., Adisa, R. & Musa, I. E. Attitude and use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in Nigeria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 9, 53 (2009).

Nergard, C. S. et al. Attitudes and use of medicinal plants during pregnancy among women at health care centers in three regions of Mali, West-Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11, 73 (2015).

John, L. J. & Shantakumari, N. Herbal medicines use during pregnancy: A review from the Middle East. Oman Med. J. 30, 229 (2015).

Pinn, G. & Pallett, L. Herbal medicine in pregnancy. Complement. Ther. Nurs. Midwifery 8, 77–80 (2002).

Van der Kooi, R. & Theobald, S. Traditional medicine in late pregnancy and labour: Perceptions of Kgaba remedies amongst the Tswana in South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 3, 11–22 (2006).

Mafuva, C. & Marima-Matarira, H. T. Towards professionalization of traditional medicine in Zimbabwe: A comparative analysis to the South African policy on traditional medicine and the Indian Ayurvedic system. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2, 154–161 (2014).

Savelyeva, T. et al. SDG3–Good Health and Wellbeing: Re-Calibrating the SDG Agenda: Concise Guides to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2019).

Budhathoki, S. S. et al. The potential of health literacy to address the health related UN sustainable development goal 3 (SDG3) in Nepal: A rapid review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 237 (2017).

Zion, D., Gillam, L. & Loff, B. The Declaration of Helsinki, CIOMS and the ethics of research on vulnerable populations. Nat. Med. 6, 615 (2000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M., together with W.N.N. conceptualised the research idea. N.M. crafted objectives, developed the methodology and data collection tools. N.M. further went on to collect data together. W.N.N. coordinated the research process and helped in drafting the manuscript with N.M. N.M. translated the data collection tools into Local Language (Isi Ndebele) and captured the data into EPI DATA and cleaned it in preparation for analysis. N.S. coded the data and performed data analysis on STATA. N.K. produced study area map. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mudonhi, N., Nunu, W.N., Sibanda, N. et al. Exploring traditional medicine utilisation during antenatal care among women in Bulilima District of Plumtree in Zimbabwe. Sci Rep 11, 6822 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86282-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86282-3

- Springer Nature Limited