Abstract

Although obesity has been associated with an increased cancer risk in the general population, the association in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) remains controversial. We conducted a dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies of body mass index (BMI) and the risk of total and site-specific cancers in patients with T2D. A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Medline until September 2020 for cohort studies on the association between BMI and cancer risk in patients with T2D. Summary relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using random effects models. Ten prospective and three retrospective cohort studies (3,345,031 participants and 37,412 cases) were included in the meta-analysis. Each 5-unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) was associated with a 6% higher risk of total cancer (RR: 1.06, 95% CI 1.01, 1.10; I2 = 55.4%, n = 6), and with a 12% increased risk in the analysis of breast cancer (RR: 1.12, 95% CI 1.05, 1.20; I2 = 0%, n = 3). The pooled RRs showed no association with prostate cancer (RR: 1.02, 95% CI 0.92, 1.13; I2 = 64.6%, n = 4), pancreatic cancer (RR: 0.97, 95% CI 0.84, 1.11; I2 = 71%, n = 3), and colorectal cancer (RR: 1.05, 95% CI 0.98, 1.13; I2 = 65.9%, n = 2). There was no indication of nonlinearity for total cancer (Pnon-linearity = 0.99), however, there was evidence of a nonlinear association between BMI and breast cancer (Pnon-linearity = 0.004) with steeper increases in risk from a BMI around 35 and above respectively. Higher BMI was associated with a higher risk of total, and breast cancer but not with risk of other cancers, in patients with T2D, however, further studies are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of high body mass index (BMI, weight in kg/height in m2) and diabetes has increased substantially over the past decades worldwide1,2. Both adiposity and diabetes are major risk factors for cancer and a range of other complications and are associated with a substantial public health burden globally3,4,5,6,7. According to the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) and evidence from some meta-analyses adiposity is an established risk factor for 12 different types of cancer including cancers of the oesophagus (adenocarcinoma), stomach (cardia), colorectal, gallbladder, pancreas, kidney, liver, endometrial, breast (postmenopausal), ovaries, and thyroid8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest increased risk of leukaemia, Hodgkin's disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma16.

Type 2 diabetes is strongly related to excess body weight17, and has been associated with increased risk of cancers of the colorectum, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, breast and endometrium, independent of BMI18. Hyperinsulinemia19, increased circulating levels of insulin growth factor-I (IGF-I)20, and alterations in sex hormones and sex hormone-binding proteins21 are some of the proposed mechanisms through which obesity and type 2 diabetes increase the risk of cancers. Moreover, higher circulating levels of adipo-cytokines22,23 and inflammatory markers24 are the two common abnormalities in obesity and diabetes, both of which are associated with cancer development23,24. It has been estimated that 5.6% of all incident cancer cases were attributable to the synergistic effects of high BMI and type 2 diabetes in 201225.

Although the associations between BMI and the risk of total and site-specific cancers in the general population have been widely investigated3,9,10,11,12,15,26, such associations in patients with existing type 2 diabetes have been less investigated and results are less clear than in general population-based studies27,28,29,30,31,32. Some studies have found a positive association with risk of total cancer31,32,33, however, not all studies have been consistent29,30,34,35, and results have been less convincing for hormone-related27,28,29,30,32,36,37,38 and colorectal cancer29,30,32.

To our knowledge, no systematic review and meta-analysis has assessed the association of BMI with the risk of total and site-specific cancers in patients with T2D. Thus, we aimed to clarify the strength and shape of the associations between BMI and the risk of overall and site-specific cancers in patients with T2D by systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Results

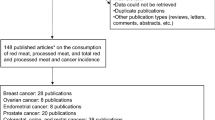

The initial database search yeilded 11,070 articles, of these, 55 were selected for full-text checking after removal of duplicate articles and the abstract/title screening. The Cohen’s κ coefficient was 0.75 at the abstract screening stage and 1.0 at the reviewing of the full-text.

The study selection process and the reasons for excluding studies are given as a flowchart in Fig. 1. Exclusion reasons are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Thirteen articles28,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, including 3,345,031 patients with T2D with age ranging from 18 to 90 year fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Detailed characteristics of the studies included in the present meta-analysis are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Ten studies were prospective cohorts28,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41 and three were retrospective cohort studies29,30,38 and in all of the them, measurement of BMI was performed at baseline of the study and prior to diagnosis of cancer. Six studies had an average follow-up duration of ≥ 10 years28,33,34,37,39,40. Four studies were conducted in North America28,33,37,40, four studies in Europe32,34,36,38, and five in Asia29,30,35,39,41. Two studies included only females33,37, three studies included only males28,36,39, and the remaining studies included both males and females29,30,32,34,35,38,40,41.The included studies were published between 2001 and 2019 and included over 37,412 cancer cases (7553 total cancer cases, 666 pancreatic cancer cases, 3387 prostate cancer cases, 839 breast cancer cases, and 24,827 colorectal cancer cases). In 10 studies, BMI was based on measured height and weight28,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, another three studies used self-reported anthropometry29,40,41. Cancer cases were recognized through national cancer registries in all studies28,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Overall, eight primary studies were of high quality28,32,33,34,36,37,38,39, with a Newcastle Ottawa study quality score ranging from 7 to 9, and another four studies had moderate quality scores, with a score of five or six (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 2 show the results of summary risk estimates for total and specific cancers per 5 -unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) in patients with T2D.

Total cancer

Four prospective and two retrospective cohort studies29,30,32,33,34,35 with 89,261 participants and 7553 cases were included in the analysis of the association between BMI and the risk total cancer in patients with T2D. The analysis indicated that each 5-unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) was associated with a 6% higher risk of total cancer incidence (RR: 1.06, 95% CI 1.01, 1.10), with high heterogeneity, I2 = 55.4%, Pheterogeneity < 0.001 (Fig. 3A). In stratified analyses, the association was positive in most subgroups although not always statistically significant, however, there was no evidence of between subgroup heterogeneity (Table 1). The analysis of cohort studies suggested a positive monotonic association between BMI with total cancer development (Pnon-linearity = 0.99) (Fig. 3B). The non-linear RRs and corresponding 95% CIs for the association between BMI and total cancer are provided in Supplementary Table S4. A significant increasing trend persisted when each study was sequentially removed from the meta-analysis (RR range: 1.04–1.08) (Supplementary Figure S1).

(A) Risk of total cancer associated with each 5-unit increase in body mass index in patients with T2D. The study-specific relative risk and 95% CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively; the area of the black square is proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The center of the open diamond presents the pooled RR and its width represents the pooled 95% CI. Weights are from the random-effects analysis. (B) Dose–response association of body mass index and total cancer risk in patients with T2D (Pnon-linearity = 0.99). (C) Risk of breast cancer associated with each 5-unit increase in body mass index in patients with T2D. The study-specific relative risk and 95% CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively; the area of the black square is proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The center of the open diamond presents the pooled RR and its width represents the pooled 95% CI. Weights are from the random-effects analysis. (D) Dose–response association of body mass index and breast cancer risk in patients with T2D (Pnon-linearity = 0.004).

Pancreatic cancer

Two prospective cohort studies38,40 with 611,083 participants and 666 cases were included in the analysis of the association between BMI and the risk pancreatic cancer in patients with T2D. There was no association between a 5-unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) and the risk pancreatic cancer (RR: 0.97, 95% CI 0.84, 1.11) with high heterogenity, I2 = 71%, Pheterogeneity = 0.06 (Supplementary Figure S2).

Colorectal cancer

Two prospective cohort studies32,41 with 2,616,417 participants and 24,827 cases were included in the analysis of the association between BMI and the risk colorectal cancer in patients with T2D. There was no association between a 5-unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) and the risk colorectal cancer (RR: 1.05, 95% CI 0.98, 1.13) with high heterogenity, I2 = 65.9%, Pheterogeneity = 0.09 (Supplementary Figure S3).

Prostate cancer

Four prospective cohort studies28,32,36,39 with 62,477 participants and 3,387 cases were included in the analysis of the association between BMI and the risk of prostate cancer in patients with T2D. There was no association between a 5-unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) and the risk prostate cancer (RR: 1.02, 95% CI 0.92, 1.13) with high heterogenity, I2 = 64.4%, Pheterogeneity = 0.04 (Supplementary Figure S4). The null association persisted across all subgroups (Table 2).

In the sensitivity analysis, sequential exclusion of each study did not materially change the summary estimate (RR range: 0.98–1.05) (Supplementary Figure S5).

Breast cancer

Two prospective and one retrospective cohort study29,32,37 with 43,352 participants and 839 cases were included in the analysis of the association between BMI and the risk breast cancer in patients with T2D. The analysis indicated that each 5-unit increase in BMI (kg/m2) was associated with an 12% increased risk of breast cancer incidence (RR: 1.12, 95% CI 1.05, 1.20), with no evidence of heterogeneity, I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.78 (Fig. 3C). The analysis suggested a positive association between BMI with breast cancer development with steeper increases in risk from a BMI around 35 (Pnon-linearity = 0.004) (Fig. 3D). The RRs (95% CIs) from the non-linear dose–response analysis of BMI and breast cancer are provided in Supplementary Table S4.

Ancilary analysis

In order to assess the potential impacts of confounding bias, the linear dose–response analyis was conducted based on crude/unadjusted risk estimates (Supplementary Figure S6).

Discussion

In this dose–response meta-analysis of 13 cohort studies on BMI and cancer risk in patients with T2D there was a significant 6% increase in total cancer risk and a significant 12% increase in breast cancer risk per 5 units increase in BMI. We also found a potential nonlinear association between BMI and breast cancer risk with steeper increases in risk from a BMI around 35, while the association with total cancer appeared to be linear. These findings are similar to those of previous meta-analyses that reported a higher risk of total cancer26 and breast cancer with increasing BMI42. However, previous meta-analyses have focused on the risk of cancer in general population and this is to our knowledge the first study to evaluate the linear and potential non-linear relationship between BMI and site-specific cancer risk in patients with T2D.

Obesity is a well-known risk factor for both diabetes and different types of cancers (17, 54). Findings from epidemiological studies also suggest that patients with T2D have increased risk of developing several cancers including colorectal (15), pancreatic (55), liver (56), gallbladder (57), breast (14), and endometrial (58) cancer. Metabolic, hormonal and physiological imbalances associated with diabetes and obesity could explain the positive association between higher BMI and cancer risk in patients with T2D. Adiposity is accompanied by insulin resistance, which is implicated in the development of cancer and tumor cells proliferation (20). Obesity-induced oxidative stress and low-grade systemic inflammation may also contribute to the increased risk of cancer in patients with T2D and excess weight (59). In addition, obesity-induced hypoxia and migrating adipose stromal cells are the emerging mechanisms linking obesity to carcinogenesis in patients with T2D (60). Moreover, estrogens and estradiol which are mainly produced by fat tissue, can activate cell proliferation and increase DNA damage in the breast and endometrial cells; resulting in tumor progression and cancer development (61).

Some limitations may have affected the results of the current analysis. As meta-analyses of observational studies are prone to the biases that are inherent in the included studies, it is possible that confounding or reverse causation could have impacted the results, and heterogeneity between studies was also observed in several analyses. Obesity and diabetes is usually associated with other unhealthy behaviors such as sedentary lifestyle, alcohol intake, smoking, dietary habits etc., which are also related to cancer incidence. Although we cannot completely rule out the possibility that confounding could have affected the results, the associations were similar in most subgroup analyses stratified by the most important confounders (age, smoking, alcohol, and physical activity) and there was no heterogeneity between these subgroups, however, there were few studies that adjusted for dietary factors or took into account use of antidiabetic medications or diabetes duration. One exception was the positive association between BMI and total cancer, which was restricted to studies with adjustment for smoking, and not observed among studies without adjustment for smoking (although the test for heterogeneity between subgroups was not significant). Smoking is a strong risk factor for a large range of cancers (62–65) and lack of adjustment or stratification for smoking could potentially confound the association with cancer toward the null as smokers tend to have a lower BMI than non-smokers43. It is possible that use of certain anti-diabetic medications could have attenuated the association between BMI and some cancers in the current analysis as some studies have suggested metformin could reduce risk of some cancers44.

We also conducted subgroup analyses stratified by study duration, study design, geographic location, but found little indication of differences across these subgroups. Reverse causation could have affected the results because several cancers are accompanied by weight loss, however, no studies excluded early follow-up to take this into account. However, since the results were similar when studies were stratified by duration of follow-up it is less likely that this may have had a substantial impact on the results as reverse causation would have affected studies with short follow-up to a larger degree than studies with long follow-up.

For pancreatic cancer our null finding was inconsistent with a previous meta-analysis which found a positive association between higher BMI and increased risk of this cancer in general population studies45. The association between BMI and colorectal cancer risk was also not significant in the current analysis, however, this was based on only two studies and the the summary estimate is overlapping with the summary estimate from a meta-analysis of studies in the general population (1.05, 0.98–1.13 vs. 1.06, 1.03–1.07)46, and suggest further studies are needed in patients with T2D. Our null finding for BMI and overall prostate cancer risk is consistent with the results from the WCRF report, however, we were not able to look at fatal and advanced cancers, for which there is evidence of increased risk8. There was a limited number of studies across specific cancers and further studies are therefore needed across most cancer sites.

Although, indices of central obesity and body fat distribution may be more appropriate predictors for cancer risk than BMI29,31,32,35,38, we were unable to examine the association of central fatness with risk of cancer in diabetes. Another point also to be noted is that there are gender differences in the incidence of some cancers47,48, and we had limited possibility to conduct gender-specific analyses because most studies did not report stratified analyses. Although menopausal status is an effect modified of the association between BMI and breast cancer risk, only one study reported results stratified by menopausal status. Finally, because almost all studies included in the present study only performed a single baseline BMI assessment, we were not able to take into account potential changes in BMI that may have occurred after baseline.

The present meta-analysis has several strengths. We included only prospective and retrospective cohort studies in the current meta-analysis and this reduced the possibility that recall bias and selection bias, which to a larger degree can affect case–control studies, could explain our findings. By combining data from several studies we had better statistical power than any of the individual studies to detect an association, but there may still have been insufficient statistical power for several of the cancers investigated because of the low number of studies. We investigated the associations for total and site-specific cancers to provide a comprehensive overview of the available data. Lastly, a relatively comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify all the relevant published literature. We also conducted dose–response analyses to clarify the shape of the associations in the analyses of total cancer and breast cancer.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies found a significant positive association between higher BMI and increased risk of total cancer and breast cancer in patients with T2D. Although, these results are limited by the low number of studies published to date, they are largely consistent with results from studies in the general population. Given the increasing global prevalence of diabetes, further high-quality prospective cohort studies are needed to evaluate the association between BMI across a larger number of cancers in patients with T2D to obtain a more complete picture of these associations.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement49 and Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guideline50 were followed as guidance for reporting this meta-analysis (Supplementary Table S5). The study protocol was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews database (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, registration No: CRD 42019132981).

Data sources and searches

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Medline databases to September 08, 2020 without any language restrictions for cohort studies in adult humans on the relationship between BMI and incidence of overall and site-specific cancers. The search query was as follows: (obesity OR body mass index) AND (cancer OR neoplasm OR carcinoma) AND (cohort OR follow-up OR prospective) AND (diabetes). The detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table S6. The bibliographies of relevant articles were also searched for potential further publications.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of the Malmo Diet and Cancer Study (MDCS)34 and Iowa Women's Health Study (IWH)33 to obtain the risk estimates of cancer in patients with T2D and data about category-specific numbers of participants/cases across categories of BMI.

Study selection

The following inclusion criteria were used to find the potential eligible articles: the studies had to be (1) based on prospective/retrospective cohort, or nested case–control study design, (2) conducted in adults with existing type 2 diabetes, (3) use self-reported or measured BMI as exposure and incidence of overall or site-specific cancers as the outcome, and (4) reporting adjusted risk estimates (odds ratios, risk ratios, or hazard ratios) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and the numbers of cases and person-years or participants/non-cases across three or more quantitative categories of BMI, or reporting sufficient data to calculate these values. Studies that presented results on a continuous scale per standard deviation (SD) or unit increment in BMI were also included. Studies were excluded if they had retrospective case–control or cross-sectional design. In case of studies that did not provide sufficient information to calculate effect sizes, corresponding authors were contacted, and of those, two studies provided additional data from their studies33,34. Two authors (SS and Sh A) independently screened the title and abstract of all articles retrieved. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus with the third author (AJ). The Cohen’s κ coefficient was calculated to indicate the interrater agreement at the abstract and full-text screening stages.

Data extraction and quality assessment

One author (SS), by using a pre-defined data-collection form, extracted the following data from included studied, which was double checked by another author (AJ): the first author’s name, publication year, study location, study design (prospective/ retrospective cohort), follow-up duration, gender and age of participants, number of participants and cases, the criteria used for type 2 diabetes diagnosis, type of cancer (overall or specific site), the method of exposure assessment (self-reported or measured), corresponding risk estimates with 95% CIs in fully adjusted models, and the confounding variables that were adjusted for. The crude crude/unadjusted risk estimates were calculated for each cancer in a sensitivity analysis to assess the potential impacts of confounding bias. The study quality was evaluated with the use of a 9-star Newcastle– Ottawa Scale51. This scale is based on the following items: representativeness of the study populations, exposure assessment, adjustment for potential confounding factors, assessment of outcome, and length and adequacy of follow-up.

Data synthesis and analysis

Estimates of the relative risk (RR) and its 95% CIs such as hazard ratios and odds ratios were considered as equal to RRs given the rarity of cancer cases in patients with T2D. Summary RRs and 95% CIs of total and site-specific cancer were estimated for each 5-unit increase in BMI with the use of a random-effects model52. The method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker53 was used for the linear dose–response analysis. The distribution of cases and participants/non-cases or person-years and adjusted risk estimates with their 95% CI for different categories of BMI were requisite input for using this method. The median point of BMI in each category was used when it was provided in the articles. For studies that reported the BMI categories in ranges we estimated the upper and lower cut-off value for open-ended categories (the first and the last categories) by using the width of the adjacent category. For studies in which the risk estimates were reported for a 1-SD or a 3- or 4-unit increment in BMI, the reported risk estimates were recalculated for a 5-unit increment in BMI. For those studies in which the lowest BMI category was not the reference category, the effect sizes were recalculated assuming the lowest category as reference, by the method described by Hamling54. If the study reported risk estimates in different age or gender subgroups, these risk estimates were pooled by a fixed-effects model to generate an overall estimate before inclusion in the main analysis. The Cochrane’s Q test and I2 statistics were used to evaluate the heterogeneity among the included studies. The following cut-off points were concidered to interperet the I2 statistic: < 25% (low heterogeneity), 25–50% (moderate heterogeneity), > 50–75% (high heterogeneity) and > 75% (severe heterogeneity)55. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were performed by the study design (prospective vs/retrospective cohort), study location (USA, Europe, and Asia), study duration (cut-off point: 10 years), and confounders adjusted (age, smoking, alcohol, physical activity) to detect the potential sources of heterogeneity. When there was at least four studies included in the analysis we also conducted sensitivity analyses excluding one study at a time to examine the impact of each study on the summary estimate. Publication bias was not evaluated owing to the small number of studies (less than 10 studies)56. Nonlinear analyses were conducted using fractional polynomial models and we determined the best fitting second order polynomial regression model, defined as the one with the lowest deviance57. A likelihood ratio test was used to assess the difference between the nonlinear and linear models to test for nonlinearity57. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhou, B. et al. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: A pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4· 4 million participants. Lancet 387, 1513–1530 (2016).

Abarca-Gómez, L. et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128· 9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 390, 2627–2642 (2017).

Renehan, A. G., Tyson, M., Egger, M., Heller, R. F. & Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371, 569–578 (2008).

Aune, D. et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ 353 (2016).

Collaborators, G. O. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27 (2017).

Collaboration, E. R. F. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 829–841 (2011).

Campbell, P. T., Newton, C. C., Patel, A. V., Jacobs, E. J. & Gapstur, S. M. Diabetes and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort of one million US adults. Diabetes Care 35, 1835–1844 (2012).

Research, W. C. R. F. A. I. f. C. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. Continuous update project expert report (2018).

Aune, D. et al. Anthropometric factors and endometrial cancer risk: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann. Oncol. 26, 1635–1648 (2015).

Aune, D. et al. Anthropometric factors and ovarian cancer risk: A systematic review and nonlinear dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cancer 136, 1888–1898 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Body mass index and risk of gastric cancer: A meta-analysis of a population with more than ten million from 24 prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 22, 1395–1408. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-13-0042 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Body mass index had different effects on premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer risks: A dose-response meta-analysis with 3,318,796 subjects from 31 cohort studies. BMC Public Health 17, 936. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4953-9 (2017).

Larsson, S. C., Mantzoros, C. S. & Wolk, A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 121, 856–862 (2007).

Larsson, S. C., Orsini, N. & Wolk, A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 97, 1679–1687 (2005).

Xie, B., Zhang, G., Wang, X. & Xu, X. Body mass index and incidence of nonaggressive and aggressive prostate cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Oncotarget 8, 97584–97592. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.20930 (2017).

Abar, L. et al. Body size and obesity during adulthood, and risk of lympho-haematopoietic cancers: an update of the WCRF-AICR systematic review of published prospective studies. Ann. Oncol. 30, 528–541 (2019).

Fruh, S. M. Obesity: Risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 29, S3-s14. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12510 (2017).

Tsilidis, K. K., Kasimis, J. C., Lopez, D. S., Ntzani, E. E. & Ioannidis, J. P. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: Umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ 350, g7607. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7607 (2015).

Vigneri, R., Goldfine, I. D. & Frittitta, L. Insulin, insulin receptors, and cancer. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 39, 1365–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-016-0508-7 (2016).

Frasca, F. et al. The role of insulin receptors and IGF-I receptors in cancer and other diseases. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 114, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813450801969715 (2008).

Hormones, E. & Group, B. C. C. Steroid hormone measurements from different types of assays in relation to body mass index and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: Reanalysis of eighteen prospective studies. Steroids 99, 49–55 (2015).

Sanchez-Jimenez, F., Perez-Perez, A., de la Cruz-Merino, L. & Sanchez-Margalet, V. Obesity and breast cancer: Role of leptin. Front. Oncol. 9, 596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00596 (2019).

Khan, S., Shukla, S., Sinha, S. & Meeran, S. M. Role of adipokines and cytokines in obesity-associated breast cancer: Therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 24, 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.10.001 (2013).

Deng, T., Lyon, C. J., Bergin, S., Caligiuri, M. A. & Hsueh, W. A. Obesity, inflammation, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 11, 421–449. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044359 (2016).

Pearson-Stuttard, J. et al. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to diabetes and high body-mass index: A comparative risk assessment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, e6–e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(18)30150-5 (2018).

Fang, X. et al. Quantitative association between body mass index and the risk of cancer: A global Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 143, 1595–1603. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31553 (2018).

Bronsveld, H. K. et al. Trends in breast cancer incidence among women with type-2 diabetes in British general practice. Primary Care Diabetes 11, 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2017.02.001 (2017).

Onitilo, A. A. et al. Prostate cancer risk in pre-diabetic men: A matched cohort study. Clin. Med. Res. 11, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2013.1160 (2013).

Xu, H. L. et al. Body mass index and cancer risk among Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Cancer 18, 795. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4675-0 (2018).

Yamamoto-Honda, R. et al. Body mass index and the risk of cancer incidence in patients with type 2 diabetes in Japan: Results from the National Center Diabetes Database. J. Diabetes Investig. 7, 908–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12522 (2016).

Duan, D. et al. Does body mass index and adult height influence cancer incidence among Chinese living with incident type 2 diabetes?. Cancer Epidemiol. 53, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2018.02.006 (2018).

Miao Jonasson, J., Cederholm, J. & Gudbjornsdottir, S. Excess body weight and cancer risk in patients with type 2 diabetes who were registered in Swedish National Diabetes Register-Register-based cohort study in Sweden. PloS One 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105868 (2014).

Anderson, K. E. et al. Diabetes and endometrial cancer in the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 10, 611–616 (2001).

Drake, I. et al. Type 2 diabetes, adiposity and cancer morbidity and mortality risk taking into account competing risk of noncancer deaths in a prospective cohort setting. Int. J. Cancer 141, 1170–1180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30824 (2017).

Yang, X. et al. Predicting values of lipids and white blood cell count for all-site cancer in type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 15, 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1677/erc-07-0266 (2008).

Hendriks, S. H. et al. Association between body mass index and obesity-related cancer risk in men and women with type 2 diabetes in primary care in the Netherlands: A cohort study (ZODIAC-56). BMJ Open 8, e018859 (2018).

Onitilo, A. et al. Breast cancer incidence before and after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women: Increased risk in the prediabetes phase. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 23, 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32836162aa (2014).

Boursi, B. et al. A clinical prediction model to assess risk for pancreatic cancer among patients with new-onset diabetes. Gastroenterology 152, 840-850.e843. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.046 (2017).

Choi, J. B. et al. The impact of diabetes on the risk of prostate cancer development according to body mass index: A 10-year nationwide cohort study. J. Cancer 7, 2061–2066. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.16110 (2016).

Stolzenberg-Solomon, R., Schairer, C., Moore, S., Hollenbeck, A. & Silverman, D. Lifetime adiposity and risk of pancreatic cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort1-3. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1057–1065. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.058123 (2013).

Lee, J. M., Lee, K. M., Kim, D. B., Ko, S. H. & Park, Y. G. Colorectal cancer risks according to sex differences in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A Korean nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 10, e00090. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000090 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Association between body mass index and breast cancer risk: Evidence based on a dose-response meta-analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 10, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s144619 (2018).

Bhaskaran, K. et al. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: A population-based cohort study of 5· 24 million UK adults. Lancet 384, 755–765 (2014).

Yu, J. H. et al. The influence of diabetes and antidiabetic medications on the risk of pancreatic cancer: A nationwide population-based study in Korea. Sci. Rep. 8, 9719 (2018).

Aune, D. et al. Body mass index, abdominal fatness and pancreatic cancer risk: A systematic review and non-linear dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann. Oncol. 23, 843–852 (2011).

Abar, L. et al. Height and body fatness and colorectal cancer risk: an update of the WCRF–AICR systematic review of published prospective studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 57, 1701–1720 (2018).

Arnold, M. et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 66, 683–691 (2017).

Kim, H.-I., Lim, H. & Moon, A. Sex differences in cancer: Epidemiology, genetics and therapy. Biomol. Ther. 26, 335 (2018).

Moher, D., Liberati, A. & Tetzlaff, J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. 2009. Manuscript submitted for publication (2018).

Stroup, D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283, 2008–2012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 (2000).

Wells, G. et al. (oxford. asp, 2017).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp. Clin. Trials 45, 139–145 (2015).

Greenland, S. & Longnecker, M. P. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 135, 1301–1309 (1992).

Hamling, J., Lee, P., Weitkunat, R. & Ambühl, M. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat. Med. 27, 954–970 (2008).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Sterne, J.A.C., Moher, D. Chapter 10: addressing reporting biases. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of intervention. Version 5.1.0 (Updated march 2011) edition. Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011, The Cochrane Collaboration.

Royston, P. A strategy for modelling the effect of a continuous covariate in medicine and epidemiology. Stat. Med. 19, 1831–1847. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0258(20000730)19:14%3c1831::aid-sim502%3e3.0.co;2-1 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Darren C. Greenwood (Clinical and Population Science Department, School of Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom) for providing the Stata code for the nonlinear dose-response analysis.

Funding

The author did not receive any funding for undertakng this systematic review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J. contributed to the conception and design of the systematic review and meta-analysis. S.S., S.A., A.J. were involved in the acquisition and analysis of the data. A.J., S.S., D.A. interpreted the results. S.S., S.A., A.J., D.A. drafted this manuscript. A.J., D.A. provided critical revisions of the systematic review. All authors reviewed and approved the submission of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soltani, S., Abdollahi, S., Aune, D. et al. Body mass index and cancer risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: a dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Sci Rep 11, 2479 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81671-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81671-0

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Potential preventive properties of GLP-1 receptor agonists against prostate cancer: a nationwide cohort study

Diabetologia (2023)

-

Body mass index and cancer risk among adults with and without cardiometabolic diseases: evidence from the EPIC and UK Biobank prospective cohort studies

BMC Medicine (2023)