Abstract

Preoperative opioid use has been shown to increase the risk for complications following total joint arthroplasty (TJA); however, these studies have not always accounted for differences in co-morbidities and socio-demographics between patients that use opioids and those that do not. They have also not accounted for the variation in degree of pre-operative use. The objective of this study was to determine if preoperative opioid use is associated with risk for surgical complications after TJA, and if this association varied by degree of use. Population-based retrospective cohort study. Older adult patients undergoing primary TJA of the hip, knee and shoulder for osteoarthritis between 2002 and 2015 in Ontario, Canada were identified. Using accepted definitions, patients were stratified into three groups according to their preoperative opioid use: no use, intermittent use and chronic use. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a composite surgical complication (surgical site infection, dislocation, revision arthroplasty) or death within a year of surgery. Intermittent and chronic users were matched separately to non-users in a 1:1 ratio, matching on TJA type plus a propensity score incorporating patient and provider factors. Overall, 108,067 patients were included in the study; 10% (N = 10,441) used opioids on a chronic basis before surgery and 35% (N = 37,668) used them intermittently. After matching, chronic pre-operative opioid use was associated with an increased risk for complications after TJA (HR 1.44, p = 0.001) relative to non-users. Overall, less than half of patients undergoing TJA used opioids in the year preceding surgery; the majority used them only intermittently. While chronic pre-operative opioid use is associated with an increased risk for complications after TJA, intermitted pre-operative use is not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the population ages, there has been an increase in the number of individuals suffering from arthritis, particularly osteoarthritis (OA)1. Historically, acute and chronic osteoarthritis pain has been managed using a combination of anti-inflammatories, injections, and physical therapy, and failing these, opioids2,3. Ultimately many patients with refractory arthritis pain will progress to total joint arthroplasty (TJA), which is generally successful at reducing pain and improving function, particularly for hip arthritis. However many patients with end-stage arthritis may be unwilling to consider arthroplasty, be unable to have one (eg: medically unwell), or may not have timely access to joint replacement (eg: wait times and insurance status). As a result, there are patients living with symptomatic OA that have failed non-opioid analgesic modalities, and have been prescribed opioids to manage their pain.

In recent years evidence has emerged to suggest that pre-operative opioid use negatively impacts outcomes and increases early complication rates following TJA4,5,6,7,8. Both OARSI and the AAOS, among some other groups, have recommended against the use of opioids for arthritis pain9,10. Although there are obvious benefits to decreasing opioid use among older patients, one clear criticism of the research to date is that it fails to stratify patients by how they use narcotics. Up until this point, pre-operative opioid use has been viewed in a binary way—use or non-use. This approach precludes the possibility that the pattern of opioid use before surgery is a factor in any potential increased risk for complications—therefore also precluding the possibility that a reduction in opioid use (if cessation is not possible) may mitigate these potential risks, akin to the impact of smoking reduction or cessation before surgery11.

Aside from the binary definition of opioid use, previous studies have also been limited by relatively small sample sizes that precluded analysis of late complications, or inadequate risk adjustment that did not fully control for the differences between opioid users and non-users. In the present study, we used a large population database to identify patients undergoing TJA of the hip, knee and shoulder, and used medication records to stratify these patients according to their pattern of opioid use based on accepted definitions: non-users, intermittent users, and chronic users. Our primary objective was to determine if the pattern of preoperative opioid use would influence post-TJA complication rates (early and late). Our hypothesis was that chronic pre-operative use of opioids would increase complication risk following TJA, but intermittent use would not.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a population-based cohort study utilizing administrative data from Ontario, Canada. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Patients in Ontario are insured under a single-payer system, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) that covers all hip, knee and shoulder total joint replacements12. All inpatient hospital stays and same day procedures are reported in the Discharge Abstract Database (inpatient procedures) and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (same day surgery)13,14,15. Both databases identify the procedures performed during the hospital stay, using Canadian Classification of Health Interventions (CCI) codes, and patient comorbidities and complications, using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision (ICD-10) codes. Study protocols were approved by IC/ES. Use of the data in this study was authorized under Section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board.

The Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) funds prescription medication for all patients aged 65 years and older. The ODB database contains a record for each prescription filled including the date, physician, number of days supplied, and drug identification number (DIN).

Baseline and post-discharge covariates for each patient were obtained from the following databases: the Registered Persons Database (RPDB), for basic demographic information on each individual; the ICES Physician Database, for surgeon demographic information and specialty; the Continuing Care Reporting System, for identifying patients treated in complex continuing care facilities; and the National Rehabilitation System database, for identifying stays at inpatient rehabilitation institutions.

Participants

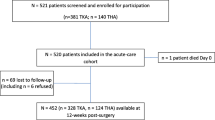

We selected patients receiving elective primary total joint replacements (hip, knee and shoulder) between April 1, 2002 and March 31, 2016 from physician and hospital records. We excluded patients who were younger than 67 years (to allow for a look-back period for pre-operative opioid use), bilateral procedures, and patients from out of province. Only the first elective joint replacement for each patient was retained. Individuals were followed for 12 months after surgery. For additional exclusions, please refer to Fig. 1.

Primary exposure

The exposure of interest was opioid use in the year immediately preceding the surgery. Opioid medications included codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine and fentanyl. Each patient was categorized as a ‘non-user’, an ‘intermittent-user’ or a ‘chronic user’ based on their opioid use during the year before surgery. ‘Non-users’ were individuals who did not fill a prescription for opioids in the year prior to their joint replacement. ‘Chronic use’ was determined using a well-established definition, and these were individuals who had at least 90 days of continuous use of opioids in this period16,17. “Continuous” in this context refers to patients that received one or multiple prescriptions in succession, where the days dispensed added up to 90 days or more. Individuals who had some use but who did not meet the criteria for chronic use were categorized as ‘intermittent-users’.

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome of interest was the occurrence of a composite complication of deep infection requiring surgery, dislocation or revision arthroplasty within one year. These complications were joint-specific—i.e. a shoulder infection did not count as a complication for someone who had a hip replacement. We used a composite outcome, as the rates of these complications at one year are generally quite low (< 0.5%)18,19,20. Additionally, we analyzed each complication individually. We additionally looked at a composite of readmission to the hospital and return to an emergency department within 30 days. These complications were identified using ICD-10 diagnostic, OHIP billing and CCI procedure codes19. Infections were identified by the occurrence of a hospital code for intra-articular infection with a confirmatory procedure code or physician claim for an irrigation and debridement, or a spacer insertion18. Revision procedures were identified using CCI codes accompanied by the supplementary status attribute “R”18.

Covariates of interest

Patient age, sex and neighbourhood income quintile were obtained from the RPDB21. Co-morbidities in the four years before surgery were categorized using the Deyo-Charlson Index22 and the Elixhauser scale23. Frailty was defined using the Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACGs) indicator (The Johns Hopkins ACG System Version 10.0)24,25. Rheumatoid arthritis was identified using a previously validated algorithm26. Income quintile and the Ontario Marginalization Index were used as surrogates for socioeconomic status27,28,29,30. Obesity was determined from surgeon billing records. Surgeon volume was defined as the number of arthroplasty procedures performed by the surgeon in the previous year19. Hospital-volume was similarly defined. Hospitals were also categorized as either ‘academic’ or ‘community’ (www.cahohospitals.com)31.

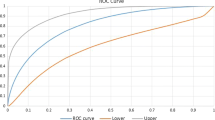

Matching and statistical analysis

Intermittent opioid users were matched to non-users by the joint being replaced (hip/knee/shoulder) and a propensity score incorporating socio-demographics (age, sex, income quintile, Ontario Marginalization Index, rurality), pre-existing health status (Charlson score, Elixhauser score, frailty, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis), provider characteristics (teaching hospital, surgeon volume, hospital volume) and the year of surgery. These patients were matched using calipers of width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score19,32 via the greedy (or “nearest neighbor without replacement”) matching method33. A matching ratio of 1:1 was used33. Patients were specifically matched by the joint replaced, such that knee replacements in intermittent opioid-users were only being compare to knee replacements in non-users, and so on.

This process was then repeated to match chronic-users to non-users. We estimated standardized differences for all covariates before and after matching, with a standardized difference of 10% or more considered indicative of imbalance34. Complications were compared between the two groups using proportional hazards survival analyses adjusted for matching All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9·3 and SAS EG 6·1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The two-tailed type I error probability was set to 0·05 for all analyses.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

Between April 1, 2002 and March 31, 2016, we identified 110,130 eligible arthroplasty recipients (Fig. 1). Most patients (n = 60,951; 55%) did not use opioids in the year prior to their joint replacement (Table 1). Approximately 10% of the cohort (n = 10,787) were chronic users of opioids prior to surgery, and the remainder (n = 38,392; n = 35%) were intermittent-users. Relative to non-users, chronic users had a higher proportion of females (66% versus 58%, p < 0.001), and a higher number of co-morbidities.

Comparing intermittent opioid-users with non-users

We successfully matched 36,250 (94%) intermittent opioid users with non-users (Table 2). After matching, absolute standardized differences were less than 10% for all measured confounders, indicating balanced (or comparable) groups. The matched analysis found no difference in the risk for our primary outcome (composite surgical complication) within one year of surgery. However, intermittent opioid users were at a slightly higher risk for readmission or return to the emergency department within 30 days (HR 1.05, p = 0.024) (Table 3).

Comparing chronic opioid users with non-users

We successfully matched 10,279 (95%) chronic opioid users with non-users (Table 2). After matching, absolute standardized differences were less than 10% for all measured confounders, indicating balanced groups. After matching, chronic opioid users were at a higher risk for our primary outcome of a composite surgical complication within one year (HR 1.44, p = 0.001). The relative increase in risk was largest for dislocation (HR 1.76, p = 0.006) (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, we used one of the largest cohorts of older adults undergoing TJA of the hip, knee and shoulder to date to show that chronic pre-operative opioid use resulted in a significantly higher risk for certain complications as compared to non-users. Equally importantly, we found that intermittent opioid use was not associated with an increased risk. This study is the first to demonstrate that the pattern of pre-operative opioid use significantly influences post-operative complication risk. It is also one of the first to demonstrate that this increased risk also affects patients undergoing hip and shoulder replacements. Above all, the findings of this study suggest that the pattern of opioid use pre-operatively should be an important consideration in perioperative discussions pertaining to complication and revision risk following TJA.

Our results indicate that the short-term use of opioids (e.g.: to deal with an acute pain crisis from arthritis) will not increase the risk for future surgical complications, whereas continued use significantly increases this risk. Furthermore, it also suggests that once a patient requires the use of opioids to manage an acute crisis of arthritic pain that they would benefit from surgical consultation, if only to discuss the option of surgery. Finally, these results also suggest that a harm reduction strategy—i.e. encouraging cessation or perhaps even a reduction of opioid use to ‘intermittent’ levels should be attempted prior to surgery. However, this will require further study.

Viewing opioid use in a binary fashion (use or no use) does not appropriately capture the manner in which patients are actually taking these medications. This is an important consideration, not only for pre-operative counseling around the risks of surgery, but also for patients in acute crisis that may need short-term pain relief prior to surgery—we feel that it would be unfair to restrict the limited short-term use of opioids for these patients. We believe that our findings indicate that when a physician is considering giving a patient a prescription for opioids that it is an appropriate time to discuss the role of surgery and arrange for a surgical consultation. The authors must stress that we believe that a concerted effort to minimize or avoid opioid use for the management of pain secondary to arthritis must continue. Not only do these medications contribute to an increased risk for complications after surgery, but opioids are ineffective and dangerous for the treatment of chronic pain, such as that resulting from osteoarthritis35.

Over the past decade, there has been increased scrutiny of perioperative opioid use among patients undergoing TJA10. Studies have compared outcomes and complication risk following TJA between patients taking opioids preoperatively (‘users’) and those who did not (‘non-users’). Generally, these studies have demonstrated that pre-operative opioid use negatively impacts outcome and increases complication risk following TJA4,5,7,8,36,37. However, some of these studies were limited in sample size and were unable to appropriately adjust for potential confounders, including patient age and co-morbidity. The current study was one of the largest to examine the impact of opioids on complications following joint replacement in older adults, and our matching strategy (by type of joint and by a propensity score encompassing several patient and provider factors) accounted for potential confounders that may have accounted for the increased risk seen in patients that take opioids.

In our cohort only 1 out of every 5 (21.9%) patients with a history of preoperative opioid use were considered chronic users. These patients were at a 44% increased risk for any surgical complication as compared to non-users, but that the risk for individual complications was also significantly higher, with a 76% greater risk for dislocation and 35% greater risk for revision within one year. Evidence to date has suggested a link between pre-operative opioid use and early TJA revision6,36, but similar observations have not been made for dislocation risk. One explanation to account for a correlation between chronic preoperative opioid use and increased post-operative dislocation risk is potential fall risk, since chronic users of opioids may continue their increased opioid use for pain management following TJA that in turn may increase their susceptibility to falls38. Alternatively, patients who chronically use opioids pre-TJA may have more advanced radiographic OA39, making their primary TJA more difficult and inherently increasing the risk for dislocation and early revision; disease severity was outside of the scope of data available to us for evaluation. Interestingly, some research suggest that perioperative opioid use increases risk for infection following TJA5, but in the present study the risk for infection but did not reach statistical significance in a comparison that controlled for several relevant confounders.

Although our evidence would suggest that intermittent opioid use prior to TJA does not significantly increase the risk of a post-TJA complication, we did observe that intermittent users were at an increased risk for an ED visit and readmission following TJA as compared to non-users. While recognizing that this result may be a chance finding due to multiple testing, it may also point to differences in pain tolerance and management or differences in post-operative functional outcomes between intermittent and non-users, and may be an interesting topic for an independent inquiry in a new cohort. A separate report from our group has found that inadequate pain control is a common reason for return to the ED following joint replacement in this jurisdiction40.

This study has several limitations. First, some patient-level data was not available to us, including the severity of OA prior to TJA and surgical details such as the type of implant. Second, this study was based upon filling an opioid prescription, not patient consumption. It remains possible that some patients who filled a prescription did not consume the entire prescription, which would have most impact on our differentiation between intermittent users and non-users. Patients who filled a prescription for opioids but did not use them are still classified as ‘intermittent’ users under our definition. Our classification of ‘chronic’ users though is likely to remain very specific, as these patients typically had multiple prescriptions, which would indicate that they were taking the opioids that they were prescribed. Third, patients may have been using opioids for several reasons, not only because of pain secondary to osteoarthritis of their hips, knees or shoulders. Finally, we did not assess outcomes such as range of motion (ROM) or patient-reported outcome scores (PROMs). It remains possible that even intermittent opioid use will negatively impact these metrics.

Overall, less than half of patients undergoing TJA use opioids in the year preceding surgery, with most of these using opioids intermittently. Although chronic opioid use prior to TJA significantly increases the risk for a post-operative complication, intermittent use does not. Moving forward, it is important that physicians understand the relationship between patterns of preoperative opioid use and complication risk following TJA, and counsel prospective TJA patients accordingly. Physicians should avoid prolonged use of opioids and should consider referring patients that require opioids for urgent surgical consultation. There may also be a benefit to deferring surgery in chronic opioid users, to give them an opportunity to minimize their use before surgery.

References

Prieto-Alhambra, D. et al. Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73(9), 1659–1664 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16(2), 137–162 (2008).

Hochberg, M. C. et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 64(4), 465–474 (2012).

Manalo, J. P. M. et al. Preoperative opioid medication use negatively affect health related quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 25(5), 946–951 (2018).

Bell, K. L. et al. Preoperative opioids increase the risk of periprosthetic joint infection after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 33(10), 3246–3251 (2018).

Bedard, N. A. et al. Preoperative opioid use and its association with early revision of total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 33(11), 3520–3523 (2018).

Hernandez, N. M., Parry, J. A., Mabry, T. M. & Taunton, M. J. Patients at risk: preoperative opioid use affects opioid prescribing, refills, and outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 33(7S), S142–S146 (2018).

Rozell, J. C., Courtney, P. M., Dattilo, J. R., Wu, C. H. & Lee, G. C. Preoperative opiate use independently predicts narcotic consumption and complications after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 32(9), 2658–2662 (2017).

McAlindon, T. E. et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22(3), 363–388 (2014).

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Information Statement: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Abuse in Orthopaedic Practice (2018). https://www.aaos.org/uploadedFiles/PreProduction/About/Opinion_Statements/advistmt/1045%20Opioid%20Use,%20Misuse,%20and%20Abuse%20in%20Practice.pdf (Accessed 2018).

Theadom, A. & Cropley, M. Effects of preoperative smoking cessation on the incidence and risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications in adult smokers: a systematic review. Tob Control. 15(5), 352–358 (2006).

Pincus, D. et al. Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA 318(20), 1994–2003 (2017).

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data Quality Documentation, National Ambulatory Care Reporting System — Current-Year Information, 2014–2015. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/nacrs-dataquality_2014-2015_en.pdf2015.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data Quality Documentation, Discharge Abstract Database — Current-Year Information, 2015–2016. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/dad-data-quality_15-16_en.pdf2016.

Canadian Institute for Health Information CCoSA. Hospitalizations and Emergency Department Visits Due to Opioid Poisoning in Canada (2016). https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Opioid%20Poisoning%20Report%20%20EN.pdf.

Chou, R. et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J. Pain 10(2), 113-130.e122 (2009).

Hansen, C. A., Inacio, M. C. S., Pratt, N. L., Roughead, E. E. & Graves, S. E. Chronic use of opioids before and after total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 32(3), 811–817 (2017).

Ravi, B. et al. Increased risk of complications following total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66(6), 254–263 (2014).

Ravi, B. et al. Relation between surgeon volume and risk of complications after total hip arthroplasty: propensity score matched cohort study. BMJ 348, g3284 (2014).

Ravi, B. et al. Association of overlapping surgery with increased risk for complications following hip surgery: A population-based Matched Cohort Study. JAMA Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6835 (2017).

Health Quality Ontario; Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care: Equity Report - Technical Appendix. http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/system-performance/health-equity-technical-appendix-2016-en.pdf2016.

Deyo, R. A., Cherkin, D. C. & Ciol, M. A. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. JClinEpidemiol. 45(6), 613 (1992).

Moore, B. J., White, S., Washington, R., Coenen, N. & Elixhauser, A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: The AHRQ elixhauser comorbidity index. Med. Care. 55(7), 698–705 (2017).

Weiner JP, Abrams C. The Johns Hopkins ACG® System: Technical Reference Guide Version 10.0. 2011.

McIsaac, D. I., Bryson, G. L. & van Walraven, C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: A population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 151(6), 538–545 (2016).

Widdifield, J. et al. Accuracy of Canadian health administrative databases in identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A validation study using the medical records of rheumatologists. Arthritis Care Res. 65(10), 1582–1591 (2013).

Agabiti, N. et al. The influence of socioeconomic status on utilization and outcomes of elective total hip replacement: a multicity population-based longitudinal study. IntJQualHealth Care. 19(1), 37 (2007).

Santaguida, P. L. et al. Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: A systematic review. Can. J. Surg. 51(6), 428 (2008).

Kralj, B. Measuring, “Rurality” for Purposes of Health Care Planning: An Empirical Measure for Ontario (Ontario Medical Association, 2005).

Matheson, F. 2011 Ontario Marginalization Index: User Guide. Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Toronto, ON: St. Michael’s Hospital; 2017. Joint publication with Public Health Ontario. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/DataAndAnalytics/Documents/User_Guide_2011_ON-Marg.pdf. Accessed 2011.

Council of Academic Hospitals of Ontario. http://caho-hospitals.com/. Accessed.

Austin, P. C. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm. 10(2), 150–161 (2011).

Austin, P. C. Comparing paired vs non-paired statistical methods of analyses when making inferences about absolute risk reductions in propensity-score matched samples. Stat. Med. 30(11), 1292 (2011).

Austin, P. C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat. Med. 28(25), 3083–3107 (2009).

Dowell, D.H.T., Chou. R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No RR-1):1–49 https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwrrr6501e1.

Bedard, N. A. et al. Does preoperative opioid use increase the risk of early revision total hip arthroplasty?. J. Arthroplasty. 33(7S), S154–S156 (2018).

Bedard, N. A. et al. Opioid use after total knee arthroplasty: trends and risk factors for prolonged use. J. Arthroplasty. 32(8), 2390–2394 (2017).

Daoust, R. et al. Recent opioid use and fall-related injury among older patients with trauma. CMAJ 190(16), E500–E506 (2018).

Knoop, J. et al. Analgesic use in patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis referred to an outpatient center: A cross-sectional study within the Amsterdam Osteoarthritis Cohort. Rheumatol. Int. 37(10), 1747–1755 (2017).

Ravi, B. et al. Factors associated with emergency department presentation after total joint arthroplasty: A population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open 8(1), E26–E33 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the ICES, a non-profit research institute funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc for use of their Drug Information Database.

Funding

This research was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research. They provided financial support subsequent to a grant competition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the development, analysis and final manuscript. B.R. is the guarantor of this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ravi, B., Pincus, D., Croxford, R. et al. Patterns of pre-operative opioid use affect the risk for complications after total joint replacement. Sci Rep 11, 22124 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01179-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01179-5

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Placebo effects in osteoarthritis: implications for treatment and drug development

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2023)

-

Two novel phages PSPa and APPa inhibit planktonic, sessile and persister populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and mitigate its virulence in Zebrafish model

Scientific Reports (2023)