Abstract

Although patients suffering from atrial fibrillation have increased worldwide, detailed information about factors associated with bleeding during direct oral anticoagulant therapy remains insufficient. We studied 1086 patients for whom direct oral anticoagulants were initiated for non-valvular atrial fibrillation between April 2011 and June 2017. Endpoints were clinically relevant bleeding or major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events until the end of December 2018. Incidences of bleeding and thrombosis were 4.5 per 100 person-years and 4.7 per 100 person-years, respectively. Most bleeding events represented gastrointestinal bleeding. Multivariate analysis revealed initiation of anticoagulants at ≥ 85 years old as significantly associated with bleeding, particularly gastrointestinal bleeding, but not major cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Other significant factors included chronic kidney disease, low-dose aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For gastrointestinal bleeding alone, histories of gastrointestinal bleeding and malignancy also showed positive correlations, in addition to the above-mentioned factors. Clinicians should pay greater attention to the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when considering prescription of anticoagulants to patients ≥ 85 years old with atrial fibrillation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bleeding is the most common adverse event in patients taking antithrombotic agents. Since this complication sometimes becomes severe and can worsen the prognosis of the original diseases, adequate management of the risk is clinically essential1. Recently, the number of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) has increased worldwide2. As this arrhythmia greatly increases the risk of serious thrombotic events such as cerebral infarction, prophylactic administration of anticoagulants is highly recommended for patients with AF3. Hemorrhagic adverse events are also frequent during anticoagulant therapy, so a balance between the risks of thrombosis and bleeding is important4,5. Novel direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) show significant prophylactic effects against thrombosis in AF patients comparable to or better than those of conventional warfarin, while the incidence of hemorrhagic complications seems lower than that with warfarin6,7,8,9. This feature is one reason why use of DOACs has been increasing over time10.

Some risk factors for bleeding in AF patients taking vitamin K antagonists have been identified. Components of the HAS-BLED score include hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, history of stroke, history of bleeding, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, and drug/alcohol abuse11,12,13,14,15. However, the impact of clinical factors on bleeding during DOAC therapy has yet to be fully elucidated, particularly in real-world settings. For example, age is one of the factors significantly affecting the incidence of bleeding in some research, with patients ≥ 75 years old showing a higher risk of bleeding. Meanwhile, very elderly patients (≥ 85 years old) are increasingly encountered in clinical settings, particularly in developed nations where the ratio of this population has increased. As the incidence of thrombosis in AF patients without anticoagulants rises rapidly with age, some researchers have claimed that anticoagulants should be administered even for the very elderly. However, clinicians might want to know which type of bleeding would increase, the severity and frequency, and related background factors. Unfortunately, we do not yet have answers to these questions, and information about the safety of DOACs for very elderly AF patients remains limited16,17,18,19.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to clarify the safety and efficacy of DOACs among patients with AF, with a focus on very elderly patients ≥ 85 years old.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study subjects. Median age was 73 years old, and 112 patients (10.3%) were ≥ 85 years old. Two-thirds of subjects were male. Median CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were 2 and 4, respectively. Types of DOAC were as follows: dabigatran, 221 (20.3%); rivaroxaban, 477 (43.9%); apixaban, 322 (29.7%); and edoxaban, 68 (6.3%). In the present study, 752 patients (69.2%) were prescribed at the recommended dose indicated in the guideline20. Conversely, 334 patients (30.8%) were treated with dosages inconsistent with recommendations, mostly with underdosing. Only for patients ≥ 85 years old, the proportion receiving the recommended dose was 62.6%, and 35.7% were underdosed. Regarding comorbidities, prevalence was 80% for hypertension, 58% for chronic heart failure (CHF), 4% for severe chronic kidney disease (CKD), and 9% for advanced malignancy. In terms of concomitant medications, low-dose aspirin (LDA) was prescribed in 20.2%, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in 3.1%, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in 54.6%.

Observation of clinical event

Table 2 demonstrates the observational data. Total observation period for the primary endpoint reached 2467.3 patient-years, and that for the secondary endpoint was 2348.8 patient-years. Relevant bleeding from any site developed in 112 patients, with an incidence of 4.5 per 100 person-years. The breakdown was gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) in 66 patients (2.7 per 100 person-years), intracranial bleeding in 9 patients (0.4 per 100 person-years), and bleeding from another site in 37 patients (1.5 per 100 person-years). Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) developed in 110 patients, with an incidence of 4.7 per 100 person-years. Of all subjects, 15 patients dropped out of follow-up (1.4% of all subjects).

Uni- and multivariate analyses

Table 3 shows the results of uni- and multivariate analyses regarding associations between bleeding and clinical factors at baseline. Development of all bleeding events correlated positively with very elderly status, CKD, LDA and NSAIDs. Regarding GIB, development of bleeding was significantly associated with the same factors, including very elderly status, along with advanced malignancies and history of GIB (Table 4).

Table 5 presents analytical results concerning MACCE. Positive factors included CHF, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and NSAIDs.

Characteristics of very elderly patients

Table 6 summarizes differences of outcomes between very elderly patients ≥ 85 years old and younger patients. The incidence of MACCE in very elderly patients was similar to that in younger patients. On the other hand, the incidence of bleeding among very elderly patients was much higher than that among younger patients. In particular, the incidence of GIB in very elderly patients was 5.9 per 100 person-years, compared to 2.4 per 100 person-years in younger patients. Intracranial bleeding developed at a higher rate in very elderly patients than in younger patients, although the number of patients investigated was small (Table 6).

Discussion

The present study indicated that initiation of DOAC for very elderly AF patients ≥ 85 years old represented a significant risk factor for hemorrhage during treatment. The incidence of all bleeding (4.5% per 100 person-years) seems comparable to that from a randomized controlled trial where the incidence of major bleeding in patients ≥ 75 years old ranged from 3.3 per 100 person-years to 5.1 per 100 person-years6,7,8,9. When limited to very elderly patients ≥ 85 years old, however, the incidence per year reached 10%, while that of younger patients remained at 4.1% (Table 6). Conversely, occurrence of MACCE showed little difference between patient groups. In comparison with previous data that showed an age-related increase in cerebral thrombosis in patients with AF when anticoagulants were not administered, the present results imply that DOACs successfully suppressed the development of thrombosis among the very elderly16,17,18,19,21,22,23. According to a prospective cohort study that enrolled 464 patients on DOACs initiated at ≥ 85 years old, the incidences of GIB and thrombotic events were 2.00 per 100 person-years and 1.84 per 100 person-years, respectively24. The main reason for the higher incidence of GIB in the present study (5.9 per 100 person-years) was presumably the higher prevalence of the use of antiplatelet agents. LDA and adenosine 2 phosphate receptor P2Y12 antagonists were prescribed at rates of 20.2% and 13.1%, respectively, in our study. On the other hand, the prevalence of antiplatelet drugs was only 6.5% in the aforementioned study24. Regarding the incidence of thrombotic events, direct comparison of our results with that study is difficult, because the endpoints of each study differed. We adopted MACCE, while Poli et al. chose systemic thrombosis. The higher prevalence of heart failure in our study might be attributable to this discrepancy. In any case, systemic embolism is often serious and accompanied by sequelae, and we basically agree with the opinion that appropriate administration of DOACs should be considered even in the very elderly, regardless of the increased risk of bleeding. However, physicians should pay greater attention to hemorrhagic complications, particularly GIB, when initiation of DOACs is planned for patients ≥ 85 years old.

The gastrointestinal tract was the most common site of bleeding, with an incidence of 2.7 per 100 person-years; this seems comparable with results from randomized trials, where the incidence of major GIB ranged from 1 to 3 per 100 person-years6,7,8,9,25,26. Risk factors for GIB resembled those for all bleeding in the present study. On multivariate analysis, very elderly patients showed a significantly higher risk of GIB, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.256. Other factors included LDA, NSAIDs, CKD, malignancy, and history of GIB. HAS-BLED score, which shows risk factors for bleeding during warfarin treatment, indicates a past history of bleeding as an obvious risk factor for future bleeding. What is known about the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with DOAC therapy is that past GIB was a significant risk. Sengupta et al. reported that at 90 days after discharge from hospitalization for initial GIB, 3.6% of patients who resumed DOACs were readmitted with recurrent GIB27. The incidence of GIB was much higher than reported in randomized trials, suggesting that a past history of GIB is strongly associated with GIB even among patients receiving DOACs. To reduce troublesome GIB, meaning a reduction of all bleeding events, avoidance of other risks is desirable; for example, the necessity for LDA or NSAIDs should be carefully reassessed, particularly in patients with CKD, history of GIB, or advanced malignancies. A previous report indicated PPIs as significant suppressors of GIB during DOAC therapy28, but this was not a significant factor underlying GIB in this study. That might be because the main site of GIB was the lower GI tract, rather than the upper GI tract in the present study. In our previous study, development of upper GIB was suppressed by PPI, whereas lower GIB was unaffected by PPI29.

Other factors significantly associated with bleeding included CKD, LDA, and NSAIDs. Concomitant administration of LDA or NSAIDs was related to not only bleeding but also MACCE. Those risks of bleeding, particularly GIB, are well known, with the mechanism of mucosal injury being the suppression of prostaglandin30,31. However, the association with MACCE remains unclear. CKD was also a factor related to bleeding. Although data about DOACs remain limited, CKD is regarded as a risk factor for both thrombosis and bleeding in patients with AF, which seems similar to our result32,33,34,35.

Clinical factors associated with MACCE differed from those associated with bleeding. Known risk factors for thrombosis in AF patients included CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, CHF, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke or ischemic attack, and vascular disease. These have been used and validated as optimal in AF patients without anticoagulants, although their applicability remains uncertain in patients on DOACs12. In the present study, CHF and PAD showed significant associations with MACCE, both of which are components of CHA2DS2-VASc score.

Limitations to this study included the single facility, the retrospective study design, and the small sample size. In particular, since only 112 patients were ≥ 85 years old, the present results should be interpreted with care. In retrospective studies, the number of dropouts might often be a problem, but remained at 1.4% in this study, and was thus considered unlikely to have exerted any substantial effect on the results. Research in multiple facilities is desirable in the future.

In conclusion, the present study showed that bleeding was common along with thrombotic events among patients taking DOACs. The most common bleeding event was GIB. Some clinical factors including very elderly status, CKD, and concomitant use of LDA and NSAIDs were significantly associated with bleeding during DOAC administration. Regarding GIB, additional coexistence of malignancy and history of GIB showed positive correlations. When initiation of DOACs is considered among very elderly patients, risk of bleeding, and GIB, in particular, should be fully assessed.

Methods

Study subjects

Participants in this study were selected from patients at a single institution in Tokyo, Japan. All 2005 patients who had been prescribed a DOAC (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban) between April 2011 and June 2017 were identified from prescription lists. Patients given DOACs for diseases other than non-valvular AF, prescribed DOACs only in hospital, or given DOACs for < 1 month were excluded. As a result, 1086 patients in total were enrolled as study subjects (Fig. 1). Primary endpoints were clinically relevant bleeding (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2–5), or discontinuation of prescription20. BARC proposes 5 bleeding types. Type 0 is no bleeding. Type 1 is bleeding that is not actionable and does not cause the patient to seek medical attention. Type 2 bleeding includes any clinically overt sign of hemorrhage that is actionable and requires diagnostic studies, hospitalization, or treatment by a healthcare professional. Type 3 bleeding is divided into 3 categories. Type 3a bleeding includes any transfusion with overt bleeding plus a hemoglobin drop of 3 to < 5 g/dL (provided the hemoglobin drop is related to bleeding). Type 3b bleeding includes overt bleeding plus a hemoglobin drop of ≥ 5 g/dL (provided the hemoglobin drop is related to bleeding), cardiac tamponade, bleeding requiring surgical intervention for control (excluding dental/nasal/skin/hemorrhoid), and bleeding requiring intravenous vasoactive agents. Type 3c bleeding includes intracranial hemorrhage and intraocular bleeding compromising vision. Type 4 bleeding is associated with procedures of coronary artery bypass grafting, such as perioperative intracranial bleeding within 48 h and reoperation after closure of sternotomy for the purpose of controlling bleeding. Type 5 bleeding is fatal. Secondary endpoints were development of MACCE including cardiac death, myocardial infarction, exacerbation of heart failure, and systemic thrombosis.

Data collection

All data were collected from the medical records of subjects. The clinical course was reviewed every month until the end of December 2018, and observations ceased when the patient reached an endpoint or stopped visiting our institution for > 6 consecutive months without documented reason (regarded as “dropout” cases). The site of bleeding was identified where possible. Baseline characteristics of subjects at the time of DOAC initiation were also investigated, including biographic data (age, sex, height, and weight), type of DOAC and initial dose, comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, CHF, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, PAD, CKD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver cirrhosis, and advanced malignant diseases), history of GIB, and concomitant medications (steroids, NSAIDs, LDA, adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12 antagonist, or PPI). Uni- and multivariate analyses were used to clarify significant relationships between development of relevant bleeding or MACCE and clinical factors. We also focused on very elderly patients ≥ 85 years old, to estimate impacts on events compared with the younger patient group.

Statistics

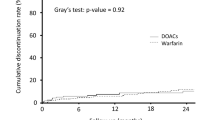

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 24 software (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Differences in ratios or values between groups were evaluated using the chi-square test or Student’s t-test. Cox proportional hazard analysis with the stepwise forward likelihood method was used in uni- and multivariate analyses, to clarify significant clinical factors related to the development of bleeding or thrombotic events. The criterion for selecting covariates for multivariate analyses was pre-specified as a value of p < 0.1 in univariate analysis. Kaplan–Meier curves were adapted to show differences in the incidence of events between groups, where significance was evaluated using log-rank testing. Values of p < 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Ethics

This protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Teikyo University prior to the study (TU19-140). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The need to obtain informed consent was waived by the ethics committee that approved the study, given the retrospective design of the study.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, K.A.; abe@med.teikyo-u.ac.jp at Teikyo University School of Medicine. These data are not publicly available, as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

Nikolsky, E., Stone, G. W. & Kirtane, A. J. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes: incidence, predictors, and clinical implications: analysis from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trial. J. Am. Col. Cardiol. 54, 1293–1302 (2009).

Colilla, S. et al. Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am. J. Cardiol. 112, 1142–1147 (2013).

Freedman, B., Potpara, T. S. & Lip, G. Y. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Lancet 388, 806–817 (2016).

Hagerty, T. & Rich, M. W. Fall risk and anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the elderly: a delicate balance. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 84, 35–40 (2017).

Foody, J. M. Reducing the risk of stroke in elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a practical guide for clinicians. Clin. Interv. Aging 23, 175–187 (2017).

Connolly, S. J. et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1139–1151 (2009).

Patel, M. R. et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 883–891 (2011).

Granger, C. B. et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 981–992 (2011).

Giugliano, R. P. et al. Once-daily edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2093–2104 (2013).

Ashburner, J. M., Singer, D. E., Lubitz, S. A., Borowsky, L. H. & Atlas, S. J. Changes in use of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation within a primary care network associated with the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants. Am. J. Cardiol. 120, 786–791 (2017).

Lip, G. Y. H., Skjøth, F., Nielsen, P. B., Kjældgaard, J. N. & Larsen, T. B. The HAS-BLED, ATRIA, and ORBIT bleeding scores in atrial fibrillation patients using non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Am. J. Med. 131(574), e13-574.e27 (2018).

Sakurai, I. et al. Clinical risk factors of stroke and major bleeding in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation under rivaroxaban: the EXPAND study sub-analysis. Heart Vessels 34, 1839–1851 (2019).

Pisters, R. et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 138, 1093–1100 (2010).

Okumura, K. et al. Validation of CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores in Japanese patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the J-RHYTHM Registry. Circ. J. 78, 1593–1599 (2014).

Kirchhof, P. et al. ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2893–2962 (2016).

Yamashita, Y. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in extreme elderly (Age >=85 years Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: the Fushimi AF registry. Chest 149, 401–412 (2016).

Patti, G. et al. Thromboembolic risk, bleeding outcomes and effect of different antithrombotic strategies in very elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: a sub-analysis from PREFER in AF. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e005657 (2017).

Kim, Y. G. et al. Impact of age on thromboembolic events in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Clin. Cardiol. 43, 78–85 (2020).

van Walraven, C. et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: the atrial fibrillation investigators. Stroke 40, 1410–1416 (2009).

Craig, T. J. et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 104–132 (2019).

Hernandez, I., Baik, S. H., Piñera, A. & Zhang, Y. Risk of bleeding with dabigatran in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 18–24 (2015).

Alnsasra, H. et al. Net clinical benefit of anticoagulant treatments in elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: experience from the real world. Heart Rhythm 16, 31–37 (2019).

Lobraico-Fernandez, J., Baksh, S. & Nemec, E. Elderly bleeding risk of direct oral anticoagulants in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Drugs R. D. 19, 235–245 (2019).

Poli, D. et al. Oral anticoagulation in very elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: results from the prospective multicenter START2-REGISTER study. PLoS ONE 14, e0216831 (2019).

Miller, C. S., Dorreen, A., Martel, M., Huynh, T. & Barkun, A. N. Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 1674-1683.e3 (2017).

Abraham, N. S., Noseworthy, P. A., Yao, X., Sangaralingham, L. R. & Shah, N. D. Gastrointestinal safety of direct oral anticoagulants: a large population-based study. Gastroenterology 152, 1014-1022.e1 (2017).

Sengupta, N., Marshall, A. L., Jones, B. A., Ham, S. & Tapper, E. B. Rebleeding vs thromboembolism after hospitalization for gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on direct oral anticoagulants. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 1893-1900.e2 (2018).

Chan, E. W. et al. Prevention of dabigatran-related gastrointestinal bleeding with gastroprotective agents: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 149, 586-595.e3 (2015).

Maruyama, K. et al. Difference between the upper and the lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking nonvitamin K oral anticoagulants. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 7123607 (2018).

García Rodríguez, L. A., Martín-Pérez, M., Hennekens, C. H., Rothwell, P. M. & Lanas, A. Bleeding risk with long-term low-dose Aspirin: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS ONE 11, e0160046 (2016).

Lip, G. Y. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 13, 963–965 (2015).

Feldberg, J. et al. A systematic review of direct oral anticoagulant use in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 34, 265–277 (2019).

Kimachi, M. et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, CD011373 (2017).

Weber, J., Olyaei, A. & Shatzel, J. The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with chronic renal insufficiency: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Haematol. 102, 312–318 (2019).

Bhatia, H. S., Bailey, J., Unlu, O., Hoffman, K. & Kim, R. J. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 42, 1463–1470 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y. collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; K.A. analyzed and interpreted the data and revised the draft; S.O. collected and analyzed the data; D.Y. collected and analyzed the data; S.K. collected and analyzed the data; Y.A. collected and analyzed the data; Kumiko K. collected and analyzed the data; Ken K. revised the draft and provided general supervision of the study; T.Y. planned the study, collected and analyzed the data; and A.T. revised the draft and provided general supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamato, H., Abe, K., Osumi, S. et al. Clinical factors associated with safety and efficacy in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants for non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Sci Rep 10, 20144 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77174-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77174-z

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: prespecified All Nippon Atrial Fibrillation in the Elderly (ANAFIE) Registry subgroup analysis

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Cardiogastroenterology: Management of Elderly Cardiac Patients at Risk of GIB

Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology (2021)