Abstract

Heightened threats for nuclear terrorism using improvised nuclear devices (IND) necessitate the development of biodosimetry assays that could rapidly assess thousands of individuals. However, the radiation exposures from an IND may be complex due to mixed fields of neutrons and photons (γ-rays), shielding from buildings, and proximity to the epicenter among others. In this study we utilized lipidomics to analyze serum samples from mice exposed to various percentages of neutrons and X-rays to a total dose of 3 Gy. Triacylglycerides, phosphatidylserines, lysophosphatidylethanolamines, lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), sphingolipids, and cholesteryl esters all showed delayed increases at day 7 compared to day 1 after irradiation, while diacylglycerides decreased in mixed field exposures and phosphatidylcholines (PCs) remained largely unchanged. Individual lipid molecules with a high degree of unsaturation exhibited the highest fold changes in mixed fields compared to photons alone. More importantly, the increased ratio of LPCs to PCs of each irradiation group compared to control could be used as a radiation biomarker and highlights the existence of a pro-inflammatory phenotype. The results showed that even a small percentage of neutrons in a mixed field can lead to high biological responses with implications for accurate biodosimetry, triage and medical managements of exposed populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear proliferation and the increased threat of nuclear terrorism with improvised nuclear devices (INDs) have accelerated the need for rapid and accurate radiation biodosimetry. Methods such as metabolomics1,2, lipidomics2,3, proteomics4,5, and transcriptomics or gene expression6,7 have been employed to develop panels of biomarkers in easily accessible biofluids to rapidly test thousands of individuals in case of an emergency in order to provide triage and appropriate medical treatment in a timely manner.

Radiation exposures encountered in an IND situation will be far more complex than single fields, i.e. γ-rays, as may be encountered in an accidental exposure or by a radiological dispersal device (RDD). It is estimated that even at 1.5 km from an IND an individual will be exposed to a mixed field of photons and neutrons. As neutrons have a high relative biological effectiveness (RBE), a low dose can lead to a significant biological effect. It has been calculated that the RBE in a mixed field may only be primarily dependent on the neutron dose and may be higher with decreasing neutron dose8. Therefore, a large population that is shielded in buildings or is situated at a distance from the epicenter where the neutrons may be less can still have a significant physiological response. It is therefore important to distinguish with the use of biological parameters the percentage of neutrons in an exposure to not only accurately estimate the absorbed dose but to further allow medical personnel to make informed decisions on a treatment course and to evaluate long term effects of radiation exposure. This is particularly important as evidence is emerging that radiation countermeasures are not universal for all types of exposures and their efficacy will depend on radiation quality9. In addition, the contribution of the more damaging radiation quality may lead to effects that can persist over years and can develop into systemic and organ specific issues, e.g. cardiovascular disease (CVD) or cancer10,11. The doses received by the atomic bomb survivors have previously been presented by Katayama et al. based on the ABD200D organ dose dosimetry system, reaching ≥4 Sv12, while Cullings et al. described in detail the evolution of the dosimetry system and the differences between Hiroshima and Nagasaki, including the neutron contribution13. Furthermore, astronauts in space and those that will take part in long term deep space missions encounter exposures to radiation particles such as neutrons, albeit different than the ones to be encountered in an IND, which can also be produced from secondary interactions of heavy ions with shielding material. As such, the neutron contribution may be significantly high and lead to biological effects such as central nervous system defects and development of CVD, to name a few. Therefore, understanding the effects of such exposures can help evaluate the risk of space radiation to missions.

We previously reported on comprehensive metabolomic and lipidomic analyses of rodent biofluids to distinguish between different radiation qualities, pure X-rays and neutron exposures14. Both metabolomics and lipidomics can provide a snapshot of the physiology at a given time point by assessing and quantifying, with relative or absolute parameters, nearly all metabolites and lipids under 1 kDa. Our previous results supported the higher damaging nature of neutrons compared to X-rays and the dyslipidemia resulting from such exposures14.

However, as mentioned earlier, real-life radiation exposure scenarios will be characterized by complexity, due to shielding and distance for example, and limitations on physical dosimetry will render accurate and rapid dosimetry difficult15. As such, it is estimated that neutrons may contribute 3% to 27% of the physical dose from an IND. Limited studies have analyzed such complicated scenarios to determine the effect of various neutron percentages in biological responses such as chromosomal aberrations16. A recent study on gene expression analysis of mouse blood determined that even small neutron contributions can have a profound effect6. Given the complexity of neutrons due to varying energies or travel patterns for example, biological responses may differ substantially depending on the energy used or percent contribution to a total dose. Additionally, the types of damage produced by the different types of irradiation are different in nature. Damage by neutrons leads to more clustered or complex lesions in DNA, as compared to electromagnetic radiation such as γ-rays and X-rays. Either of those types can be severely damaging and a mixed exposure may lead to higher levels of damage. We have therefore aimed to determine changes in the circulating lipidome following exposure to various neutron contributions to a total dose of 3 Gy and a comparable neutron total dose of 0.75 Gy with a 0.15 Gy γ-ray contribution, based on an assumed RBE of ~414,17. This RBE is based on initial micronuclei studies by Xu et al.17, and has been implemented across our studies for our initial studies of neutron exposures on the metabolome and lipidome, although RBE calculations and especially for mixed fields can be far more complex. As previously presented, we utilized an accelerator neutron irradiation facility (Columbia University, Radiological Research Accelerator Facility RARAF)14,17,18, simulating neutrons similar to the Hiroshima atomic bomb spectrum, with an approximate 17–20% γ-ray component and energies between 0.2 and 9 MeV14,17,18. Lipidomics, defined as the collective assessment of all lipids in a sample with the use of modern liquid chromatography (LC) mass spectrometry (MS) techniques, showed delayed circulating increases in species from various lipid classes, with specific classes and individual lipids allowing for the distinction of the percentage of neutrons in the total dose. This is the first study to analyze mixed neutron/X-ray fields with lipidomics and can serve as the basis for dissecting complex biological interactions resulting from such irradiations. Potential long-term monitoring of such responses could also be correlated to biological effects and their severity.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All solvents were of the highest purity Optima LC-MS (Fisher Scientific). Internal standards used for lipid class retention time determination and normalization were included in the single mixture SPLASH® Lipidomix® mass spec standard (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc).

Experimental design and sample collection

Male C57BL/6J mice, 8–10 week old, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and acclimated at Columbia University for one week prior to irradiation. All groups consisted of 5 mice per group. Mice were housed under standard housing conditions, with food and water ad libitum and 12:12 h light:dark cycle conditions. All experiments were approved by the Columbia University IACUC (#AC-AAAQ2410). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Blood was collected at euthanasia at day 1 and 7 after irradiation via terminal cardiac puncture and serum was collected with serum separators (BD Microtainer® tubes, Becton Dickinson and Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Blood was allowed to clot for 30 minutes at room temperature, centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min at 12,000 × g, transferred to Eppendorf tubes and immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C until shipment to Georgetown University.

Irradiation and dosimetry

Irradiation and dosimetry have been previously described14,18 with use of custom holders in a Ferris wheel system to average the spatial inhomogeneity in the neutron beam. Mice were acclimated two times in their holders prior to irradiations for 15 min each. For mixed irradiations, mice were first irradiated with neutrons with an inherent γ-ray contribution of ~17%, followed immediately by X-irradiation for a total dose of 3 Gy. All mice that did not receive neutron irradiations were also subjected to the same treatment conditions, minus neutron exposure. Dose rates were as follows: neutrons 0.96 Gy/h, γ-rays 0.17 Gy/h, X-rays 1.23 Gy/min. The irradiation scheme per group is described in Table 1. No apparent radiotoxicity was observed in any of the mice over this 7-day study.

Sample preparation and analysis

Twenty five μl of serum were diluted with cold chloroform:methanol (2:1) in a 1:4 v/v ratio in a siliconized tube. Samples were vortexed and allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 min. Samples were vortexed again and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 × g at room temperature. The bottom organic phase was carefully transferred to a separate siliconized tube and vacuumed dried with no heat. The lipids were dissolved in 150 μl of 50:25:25% isopropanol:acetonitrile:water and 10 μl of SPLASH® Lipidomix® mass spec standard mixture (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, Alabama) were added to each sample.

Two μl were injected into an Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system by Waters Corporation for chromatographic separation. A CSH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) was used for chromatography at 60 °C. Mobile phase A included 50:50 water:acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid +10 mM HCOONH4 and mobile phase B included 90:10 isopropanol:acetonitrile +0.1% formic acid +10 mM HCOONH4. The chromatographic gradient was set as follows: 0–8 min 60% A and 40% B, 8–9 min 100% B, 9–13 min 60% A and 40% B, with a flow rate of 0.45 mL/min. The UPLC was coupled to a Xevo G2® QTOF-MS (Waters, Milford MA), operated in both positive and negative ionization mode (ESI+ and ESI−) in MSE function. Accurate mass was obtained by intermittent injections of leucine enkephalin used as Lockspray®. Quality controls from pooled samples were injected every 10 samples in order to monitor for retention time drift and chromatographic integrity. Chromatographic data were deconvoluted with the software Progenesis QI (NonLinear Dynamics, Newcastle UK) and peak alignment was conducted based on the best quality control sample chosen by the software. Putative identities for lipid class assignment were assigned through the database LIPID MAPS19. Only ions that had a putative identity were further scrutinized. The list of potential metabolites was further reduced by including only ions whose retention time was close to their class’ internal standard. Furthermore, only ions that had theoretical fragmentation matching to a lipid identity through Progenesis QI or an identified characteristic neutral loss, i.e. 184 m/z for PCs and LPCs.

Upon reduction of the list of putative metabolites, LPCs were normalized to 18:1(d7) LPC [M + H]+ = 529.3992 at 1.31 min, sphingomyelins (SMs) were normalized to 18:1(d9) SM [M + H]+ = 738.6483 at 4.67 min, phosphatidylcholines (PCs) to 15:0–18:1(d7) PC [M + H]+ = 753.6483 at 4.96 min, triacylglycerides (TGs) to 15:0–18:1(d7)-15:0 TG [M + NH4]+ = 829.7988 at 7.66 min, lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPEs) to 18:1(d7) LPE [M-H]− = 485.4465 at 1.3 min, and phosphatidylserines (PSs) to 15:0–18:1(d7) PS [M + Na-2H]− = 797.6041 at 4.9 min. The chromatographic separation of the internal standards is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. All other lipid classes that did not have a specified internal standard were normalized with the function “normalize to all compounds” through the software Progenesis QI.

Normalized data from both ESI+ and ESI− were combined to form a single spreadsheet. The data were analyzed with the statistical software MetaboAnalyst 4.020. Features with >75% of missing values were removed and variables with missing data were excluded. Data was Pareto scaled and statistically significant ions across all groups [false discovery rate (FDR) p-value < 0.05] were identified with the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test. Heatmaps with the Euclidean distance measure and the clustering algorithm Ward were constructed with group averages. Data were also analyzed with the statistical software package MetaboLyzer21. Briefly, complete-presence ions with at least 70% presence in both control and experimental groups, were analyzed with Welch’s t-test, while partial-presence ions (70% presence in only one group) were analyzed categorically with the Barnard’s test. Outliers were removed via 1.5 interquartile range (IQR) based. Values with zero abundance were excluded from the analysis. P-values were corrected with the Benjamini-Hochberg step-up FDR procedure (FDR < 0.1). Volcano plots were constructed from the complete presence ions, graphed as –log10 FDR corrected p-value versus log2 fold change.

Graphical representation was conducted with Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Outliers were identified with the ROUT method with Q set to 1%. P-values within each cluster of groups were calculated with the Kruskal Wallis test and multiple comparisons test through Dunn’s test, with a p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Error bars are shown as standard error of the mean (SEM). Fold changes were calculated by dividing one experimental condition with another. Only fold changes of at least 1.5 (increased or decreased) were marked in supplementary tables.

Results

Mixed neutron irradiation fields were achieved by first irradiating with varying doses of neutrons, as previously described14,17,18, followed shortly by X-ray irradiations to a total dose of 3 Gy. Groups were therefore designated as sham (controls), 0% (no neutrons) and an equitoxic dose of the neutron source (0.75 Gy) designated as 83%; the mixed field samples were designated 5% (0.15 Gy out of 3 Gy total), 15% (0.45 Gy out of 3 Gy total), and 25% (0.75 Gy out of 3 Gy total) (Table 1). For the neutron beam only (83%) relative toxicity has been previously assessed using a micronucleus approach17. Percent coefficient variance (%CV) and average values of the internal standards are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Initial analysis determined whether the neutron contribution can be detectable when compared to a pure X-ray dose. Volcano plots (Supplementary Fig. 2A) at day 1 after IR showed limited responses based on the neutron contribution, however at day 7 responses were augmented, with high levels of statistically significant ions at 15% neutrons and higher. Similar results were obtained when compared to sham irradiated (controls), as seen in Supplementary Fig. 2B; however, even a small percentage of neutrons (5%) was able to mount a more severe response indicating higher damage responses compared to pure photons.

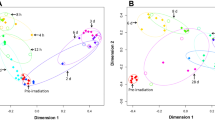

Figure 1A shows the collective number of statistically significant features when comparing each exposure to controls (left panel) or to pure photons (right panel). A percentage dependent increase of lipidomic changes was evident compared to controls, although the 83% group showed a decrease in the total number of lipids, potentially signifying a higher degree of systemic damage that is associated with neutrons and has been cleared. The 5–25% groups therefore indicate the possibility of an additive response with the different radiation qualities compared to controls. Investigating the contribution of the neutrons to the overall signature compared to pure photons (Fig. 1A, right panel), 5% neutrons contributed minimally to lipidomic changes, while the 83% group showed a moderate response. The intermediate groups however (15 and 25%), highlighted the potential existence of a threshold for lipidomic responses and a synergistic effect of a mixed neutron/photon field to elicit a robust lipidomic response. A heatmap of day 7 data depicting the patterns of the top 100 lipids determined through a Kruskal Wallis test is shown in Fig. 1B, with the 25% group showing the highest changes compared to the other groups.

Statistically significant lipids were identified through the software MetaboAnalyst20 with a Kruskal Wallis test with FDR correction. All identities were based on searches through the database LIPID MAPS19, retention time proximity to the internal standard for each class, and existence of theoretical fragmentation pattern matching in Progenesis QI. Lipid classes that were identified in ESI+ include TGs, CEs, sphingolipids, DGs, LPCs, and PCs. Lipid classes that were perturbed in ESI− include LPEs and PSs. In particular, 153 TGs were identified, 5 CEs, 6 sphingolipids, 7 DGs, 5 LPCs, 59 PCs, 4 LPEs, and 21 PSs (Supplementary Tables 2–13). Fold-change calculation was conducted by dividing mixed or pure neutrons (5–83%) to photons (0%) (Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11) or irradiated groups to controls (Supplementary Tables 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13). Fold changes were considered important if the ratio was ≥1.5 or ≤0.67 (representing a 1.5 fold decrease) for decreased levels and labeled with the symbol • in each Supplementary Table. The greatest fold changes were observed at day 7 [e.g. TG(63:10) reached >9 fold change compared to photons (Supplementary Table 3)]. The fold changes and increases were more pronounced in TGs with the higher carbon content and polyunsaturation levels, indicating the existence of processes such as cell damage and oxidative stress. Similar patterns were observed for PCs, while LPEs and PSs showed comparable changes at both days.

Representative lipids from six different classes are shown in Fig. 2. TG(60:9), PS(41:5), and LPC(20:1) all showed mixed field increases when compared to controls or photons (0%) at day 7. LPE(20:2) showed early responses at day 1 that persisted in irradiated groups compared to control at day 7, while SM(d18:1/22:1) showed decreased changes in the mixed field groups. Finally, CE(18:2) showed a statistically significant increase in the 83% group at day 7, with no changes observed in the other groups.

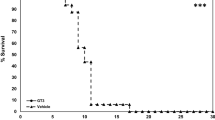

To determine whether lipid classes exhibited differential levels based on the different experimental conditions, the normalized abundance levels of the identified lipids (Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11) were summed within each sample. This allowed for the collective assessment of each lipid class in each sample and group. Results for TGs, DGs, LPCs, and PSs are shown in Fig. 3. At day 1, only PSs and DGs showed statistically significant changes (p = 0.0129 for DGs and p = 0.0103 for PSs). However, at day 7 all four lipid classes showed significant changes with a p < 0.05, with TGs, LPCs, and PSs levels increasing with increasing neutron percentage. DGs on the other hand showed a pattern in the opposite direction, that mirrors the increases in TGs in each group. CEs, PEs, and sphingolipids total responses were less pronounced (data not shown). Since the ratio of LPCs to PCs is generally indicative of a pro-inflammatory response and phospholipase A activity, we calculated the ratio of LPC/PC between each irradiation condition compared to control (Fig. 4A). Results showed that mixed field irradiation had a dramatic contribution to this increased ratio, while pure photons only showed such a response at the later time point. The neutron beam only (83%) on the other had a very mild response compared to controls. Taken all together to identify patterns of changes in overall lipid classes, Fig. 4B shows a simplified version of the pathways of lipid biosynthesis in the first week after irradiation, as explored in this study and the interpathway connectivity.

Total lipid abundance at day 1 and day 7 post irradiation. PSs, LPCs, and TGs all showed patterns of significant increases in the mixed neutron fields, which DGs mirrored the pattern of TGs and showed decreased overall levels with time. P-values were calculated with a Kruskal Wallis test with multiple comparison correction. Lines represent mean ± standard error of the mean (n per group is 5).

Panel (A) Ratio of total LPC to PC, normalized to mean control levels depicting the increased inflammatory nature of mixed field irradiations (n per group is 5). Panel (B) Lipid biosynthesis and altered patterns of neutron/X-ray exposures relative to control in the first week post irradiation. Lipid class abbreviations: CE, cholesteryl ester; DG, diacylglycerol; FA, fatty acid; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; TG, triacylglyceride.

Discussion

This study focused on the effects of mixed neutron/photon irradiations on the mouse lipidome and whether such alterations can be used to estimate the percent of neutrons in the total absorbed dose for biodosimetry purposes. We previously reported on the radiation quality differences with equidose or equitoxic doses14, where we showed that neutrons exhibited a persistently higher degree of circulating lipids molecules compared to pure photons. Such collective changes were validated in this study (Fig. 1A, left panel). Lipid perturbations following whole body exposures have been well documented in multiple species and particularly in atomic bomb survivors2,22,23,24,25,26. However, specific lipids from different classes that could be used as biomarkers have been less characterized. Due to increased oxidative stress associated with ionizing radiation, lipid peroxidation and pro-inflammatory lipid intermediates can have immediate effects on physiology and even lead to longer term effects, such as development of CVD, lung injury, and even cancer27,28. Additionally, apoptosis from the direct action of radiation injury or even initiation of such processes from activation of lipid intermediates, as in activation of sphingomyelinase to generate ceramide from hydrolysis of sphingomyelin29, can lead to pathogenesis of normal tissue. Products of processes like these however can be mined as biomarkers to be used for assessment of exposures. Efforts such as this have been undertaken with gene expression studies with identical exposures as the ones we described here6. Pathways identified and related to metabolism included amino acids and fatty acid metabolism, as previously determined in metabolomic studies in urine and serum14, with significant downregulation of genes encoding for ribosomal proteins6. A future metabolomics specific analysis will address any perturbations in these pathways with a mixed field. These investigators also determined that the number of differentially expressed genes increased with the percentage of neutrons in the mixed field, except for the 25% group possibly reflecting increased damage6.

Our results showed that when compared to controls, there is a percentage mixed field dependent increase in statistically significant ions. Interestingly, the 83% group (0.75 Gy of neutrons) had a lower level of statistically significant ions compared to the 25% group (0.75 Gy of neutrons), although the collective number at the 25% vs. C suggests a synergistic rather than an additive interaction between the two types of radiation exposure. Possible explanations for this could include not only higher apoptotic products but also mechanisms resulting from increased oxidative stress that amplify the signal from a mixed field irradiation. When investigating the contribution of the neutron exposure to the total dose, as seen in Fig. 1A right panel, the 15 and 25% contributions appeared to have a similar effect when compared to photons alone (Fig. 1A). Compared to the 5% group, this suggests the existence of a possible threshold effect regarding lipidomic responses. Compared to pure photons (0%) and to “pure” neutrons (83%), the effect appears to be synergistic for both 15 and 25%, as when compared to controls.

The majority of the lipid responses showed the most pronounced changes at the later time point (day 7). Total TGs were severely increased at D7 compared to both control and pure photons (0%). Interestingly, TGs with high carbon and double bond content showed the highest fold changes at day 7. Such increases of species of TGs have previously been identified in non-human primates and attributed to increased oxidative stress30. Although the primary TG source is from dietary intake, the mirrored decrease in circulating DGs, coupled with no differences in body weight between the groups (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggests the possibility that such TG formation is of endogenous origin. Accumulation of TGs has been linked to increased macrophage apoptosis through mitochondrial dysfunction31 and increased risk of CVD, including atherosclerosis. Epidemiological studies of A-bomb survivors have shown increased risk of CVD and hypertension10,32,33,34. Increased levels of PSs also highlight the increased levels of apoptosis associated with radiation exposure, as PSs are used by cells as a clearance signal35, although the total levels are non-radiation quality specific. However, individual lipid molecules, such as PS(41:5) highlighted in Fig. 2 can be used as biomarkers associated with specific radiation qualities at later time points.

Along with increased TGs, high levels of circulating LPCs have also been linked to increased atherosclerosis36,37. LPCs are pro-inflammatory in nature and can be formed from oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL)36,37. LPCs are also generated from hydrolysis of PCs through the enzymatic process of phospholipase A2. The ratio of LPC levels to PC levels has found utility as a good biomarker of increased inflammation38. In our study mixed field neutron exposures showed significantly higher levels compared to unirradiated controls, particularly at the later time point (Fig. 4A), highlighting the underlying inflammatory nature associated with mixed field irradiations, which is much higher than photons alone. As previously determined in our studies14, pure neutron irradiations are associated with a severe downregulation of metabolic processes and even pro-inflammatory lipid intermediates such as linoleic acid and arachidonic acid. A low ratio of LPC to PC has been associated with increased mortality in septic patients39, therefore it will be interesting to conduct long term studies and link the levels of these lipid classes to mortality associated with mixed field exposures.

Compared to our previously published study14, this study validated the patterns that were identified. Previous analysis of equidoses (1 Gy neutrons compared to 1 Gy X-rays) showed increased TGs, LPEs, and LPCs one week after irradiation, similar to what was observed in this more detailed analysis. Validation therefore of the results with an independent study highlights that neutron exposures can lead to higher responses that may potentially contribute to downstream effects. It remains to be seen what long-term effects will arise from mixed field irradiations and whether biomarkers for each % neutron contribution will persist overtime, as with the LPC/PC ratio. Nonetheless, early effects from mixed field irradiations can be identified through lipidomics and specific lipid species or classes utilized for determining the type of irradiation and potential health effects that can arise from such exposures. Furthermore, as this was an animal study with controlled experimental conditions, e.g. diet and genotype to name a few, it still remains to be seen whether similar results would be obtained in a real life scenario. Additionally, future research with lipidomics should also address the differences in populations such as underlying infections and increased stress, however our previous study on pure neutrons showed a significant downregulation of free fatty acids14, opposite of what is expected during an infection40. Nonetheless, this study provides valuable insight in the action of mixed beams on the lipidome.

References

Menon, S. S. et al. Radiation Metabolomics: Current Status and Future Directions. Front Oncol 6, 20 (2016).

Pannkuk, E. L., Fornace, A. J. & Laiakis, E. C. Metabolomic applications in radiation biodosimetry: exploring radiation effects through small molecules. Int J Radiat Biol 93, 1151–1176 (2017).

Jelonek, K., Pietrowska, M. & Widlak, P. Systemic effects of ionizing radiation at the proteome and metabolome levels in the blood of cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: the influence of inflammation and radiation toxicity. Int J Radiat Biol 93, 683–696 (2017).

Nongrum, S. et al. Identification and Preliminary Validation of Radiation Response Protein(s) in Human Blood for a High-throughput Molecular Biodosimetry Technology for the Future. Genome Integr 8, 5 (2017).

Sharma, M. & Moulder, J. E. The urine proteome as a radiation biodosimeter. Adv Exp Med Biol 990, 87–100 (2013).

Broustas, C. G., Harken, A. D., Garty, G. & Amundson, S. A. Identification of differentially expressed genes and pathways in mice exposed to mixed field neutron/photon radiation. BMC Genomics 19, 504 (2018).

Lacombe, J., Sima, C., Amundson, S. A. & Zenhausern, F. Candidate gene biodosimetry markers of exposure to external ionizing radiation in human blood: A systematic review. PLoS One 13, e0198851 (2018).

Sasaki, M. S., Endo, S., Hoshi, M. & Nomura, T. Neutron relative biological effectiveness in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors: a critical review. J Radiat Res 57, 583–595 (2016).

Cary, L. H., Ngudiankama, B. F., Salber, R. E., Ledney, G. D. & Whitnall, M. H. Efficacy of radiation countermeasures depends on radiation quality. Radiat Res 177, 663–675 (2012).

Douple, E. B. et al. Long-term radiation-related health effects in a unique human population: lessons learned from the atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 5(Suppl 1), S122–33 (2011).

Sera, N., Hida, A., Imaizumi, M., Nakashima, E. & Akahoshi, M. The association between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease risk factors in atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res 179, 46–52 (2013).

Katayama, H. et al. Reassessment of the cancer mortality risk among Hiroshima atomic-bomb survivors using a new dosimetry system, ABS2000D, compared with ABS93D. J Radiat Res 43, 53–64 (2002).

Cullings, H. M. et al. Dose estimation for atomic bomb survivor studies: its evolution and present status. Radiat Res 166, 219–254 (2006).

Laiakis, E. C. et al. Metabolic Dysregulation after Neutron Exposures Expected from an Improvised Nuclear Device. Radiat Res 188, 21–34 (2017).

Kramer, K., Li, A., Madrigal, J., Sanchez, B. & Millage, K. Monte-Carlo Modeling of the Prompt Radiation Emitted by a Nuclear Device in the National Capital Region, Revision 1 (2016).

Ballarini, F. et al. Estimating mixed field effects: an application supporting the lack of a non-linear component for chromosome aberration induction by neutrons. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 103, 19–28 (2003).

Xu, Y. et al. Accelerator-Based Biological Irradiation Facility Simulating Neutron Exposure from an Improvised Nuclear Device. Radiat Res 184, 404–410 (2015).

Xu, Y. et al. Broad Energy Range Neutron Spectroscopy using a Liquid Scintillator and a Proportional Counter: Application to a Neutron Spectrum Similar to that from an Improvised Nuclear Device. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 794, 234–239 (2015).

Sud, M. et al. LMSD: LIPID MAPS structure database. Nucleic Acids Res 35, D527–32 (2007).

Chong, J. et al. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res (2018).

Mak, T. D., Laiakis, E. C., Goudarzi, M. & Fornace, A. J. MetaboLyzer: a novel statistical workflow for analyzing Postprocessed LC-MS metabolomics data. Anal Chem 86, 506–513 (2014).

Kagan, V. E. et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 13, 81–90 (2017).

Laiakis, E. C. et al. Metabolic phenotyping reveals a lipid mediator response to ionizing radiation. J Proteome Res 13, 4143–4154 (2014).

Laiakis, E. C. et al. A Serum Small Molecule Biosignature of Radiation Exposure from Total Body Irradiated Patients. J Proteome Res 16, 3805–3815 (2017).

Mu, H. et al. Ionizing radiation exposure: hazards, prevention, and biomarker screening. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 25, 15294–15306 (2018).

Wong, F. L., Yamada, M., Sasaki, H., Kodama, K. & Hosoda, Y. Effects of radiation on the longitudinal trends of total serum cholesterol levels in the atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res 151, 736–746 (1999).

Yahyapour, R. et al. Reduction-oxidation (redox) system in radiation-induced normal tissue injury: molecular mechanisms and implications in radiation therapeutics. Clin Transl Oncol 20, 975–988 (2018).

Zhao, W. & Robbins, M. E. Inflammation and chronic oxidative stress in radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: therapeutic implications. Curr Med Chem 16, 130–143 (2009).

Kolesnick, R. & Fuks, Z. Radiation and ceramide-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 22, 5897–5906 (2003).

Pannkuk, E. L. et al. A Lipidomic and Metabolomic Serum Signature from Nonhuman Primates Exposed to Ionizing Radiation. Metabolomics 12 (2016).

Aflaki, E. et al. Triacylglycerol accumulation activates the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway in macrophages. J Biol Chem 286, 7418–7428 (2011).

Little, M. P. Cancer and non-cancer effects in Japanese atomic bomb survivors. J Radiol Prot 29, A43–59 (2009).

Ozasa, K., Takahashi, I. & Grant, E. J. Radiation-related risks of non-cancer outcomes in the atomic bomb survivors. Ann ICRP 45, 253–261 (2016).

Takahashi, I. et al. A report from the 2013 international workshop: radiation and cardiovascular disease, Hiroshima, Japan. J Radiol Prot 33, 869–880 (2013).

Segawa, K. & Nagata, S. An Apoptotic ‘Eat Me’ Signal: Phosphatidylserine Exposure. Trends Cell Biol 25, 639–650 (2015).

Matsumoto, T., Kobayashi, T. & Kamata, K. Role of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) in atherosclerosis. Curr Med Chem 14, 3209–3220 (2007).

Takahashi, M. et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine induces apoptosis in human endothelial cells through a p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism. Atherosclerosis 161, 387–394 (2002).

Zhang, W. et al. Lysophosphatidylcholines to phosphatidylcholines ratio predicts advanced knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 55, 1566–1574 (2016).

Mecatti, G. C. et al. Lipidomic Profiling of Plasma and Erythrocytes From Septic Patients Reveals Potential Biomarker Candidates. Biomark Insights 13, 1177271918765137 (2018).

Dennis, E. A. & Norris, P. C. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 15, 511–523 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) grant U19 AI067773 (P.I. David J. Brenner, performed as part of Columbia University Center for Medical Countermeasures against Radiation). The project described above was also supported by Award Number P30 CA051008 (P.I. Louis Weiner) from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P.C. and L.S. performed the animal experiments and sample collections. A.D.H. and G.Y.G. performed the dosimetry. A.D.H. and V.G. performed the irradiations. E.C.L. performed the sample preparation, analysis, and interpretation of the results. G.A. also contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to discussions on conducting the experiments and scientific interpretation of the results and provided input and approval of the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laiakis, E.C., Canadell, M.P., Grilj, V. et al. Serum lipidomic analysis from mixed neutron/X-ray radiation fields reveals a hyperlipidemic and pro-inflammatory phenotype. Sci Rep 9, 4539 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41083-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41083-7

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Metabolomics and transcriptomics based multi-omics integration reveals radiation-induced altered pathway networking and underlying mechanism

npj Systems Biology and Applications (2023)

-

Development of Polymer Composites in Radiation Shielding Applications: A Review

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2023)

-

An optimized method for the isolation of urinary extracellular vesicles for molecular phenotyping: detection of biomarkers for radiation exposure

Journal of Translational Medicine (2022)

-

A High Throughput Approach to Reconstruct Partial-Body and Neutron Radiation Exposures on an Individual Basis

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Systemic modulation of stress and immune parameters in patients treated for prostate adenocarcinoma by intensity-modulated radiation therapy or stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy

Strahlentherapie und Onkologie (2020)