Abstract

Superconductors with a van der Waals (vdW) structure have attracted a considerable interest because of the possibility for truly two-dimensional (2D) superconducting systems. We recently reported NaSn2As2 as a novel vdW-type superconductor with transition temperature (Tc) of 1.3 K. Herein, we present the crystal structure and superconductivity of new material Na1−xSn2P2 with Tc = 2.0 K. Its crystal structure consists of two layers of a buckled honeycomb network of SnP, bound by the vdW forces and separated by Na ions, as similar to that of NaSn2As2. Amount of Na deficiency (x) was estimated to be 0.074(18) using synchrotron X-ray diffraction. Bulk nature of superconductivity was confirmed by the measurements of electrical resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and specific heat. First-principles calculation using density functional theory shows that Na1−xSn2P2 and NaSn2As2 have comparable electronic structure, suggesting higher Tc of Na1−xSn2P2 resulted from increased density of states at the Fermi level due to Na deficiency. Because there are various structural analogues with tin-pnictide (SnPn) conducting layers, our results indicate that SnPn-based layered compounds can be categorized into a novel family of vdW-type superconductors, providing a new platform for studies on physics and chemistry of low-dimensional superconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superconducting behavior with exotic characteristics is often observed in materials with a layered two-dimensional crystal structure. Low dimensionality affects the electronic structure of these materials, potentially leading to high transition temperatures (Tc) and/or unconventional pairing mechanisms1,2. Among the layered superconductors, much attention has been paid to the van der Waals (vdW) materials because of the possibility for truly two-dimensional (2D) superconducting systems3,4,5,6. Owing to the recent development on the mechanical exfoliation techniques, various vdW materials are found to be suitable to make a 2D system by reducing their thickness down to the level of individual atomic layers7. As an example, atomically-thin NbSe2 crystals turn out to host unusual superconducting states, including Ising superconductivity with a strong in-plane upper critical field4 and a field-induced Bose-metal phase under the out-of-plane magnetic field5. In order to clarify the underlying mechanisms of such exotic states and to investigate whether or not they are generic, further studies, particularly on different types of vdW superconductors, are highly desirable.

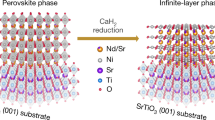

We recently reported the discovery of NaSn2As2 superconductor with Tc = 1.3 K8. NaSn2As2 crystallizes in a trigonal R\(\bar{3}\,\)m unit cell, consisting of two layers of a buckled honeycomb network of SnAs, bound by the vdW forces and separated by Na ions9, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a,c. Because of the vdW gap between the SnAs layers, it can be readily exfoliated through both mechanical and liquid-phase methods9,10. Besides, the sister compound SrSn2As2, having a crystal structure analogous to NaSn2As2, has been theoretically suggested to be very close to the topological critical point, hosting three-dimensional Dirac state at the Fermi level11, which was experimentally investigated by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy12. There are various structural analogues with conducting tin-pnictide (SnPn) layers, including Sn4Pn313,14 and ASnPn15,16,17,18,19, as well as ASn2Pn29,10,12,20,21,22, where A denotes alkali or alkaline earth metal (see Fig. 1). Indeed, Sn4Pn3 was reported to be a superconductor with Tc = 1.2–1.3 K23,24, although detailed superconducting characteristics have not been reported. In addition to these superconductors, ASnPn is attractive for thermoelectric application because of its relatively low lattice thermal conductivity lower than 2 Wm−1 K−1 at 300 K, most likely due to lone-pair effects16,25. These results strongly suggest that SnPn-based layered compounds can be regarded as a novel family of vdW-type compounds exhibiting various functionality.

Schematic representations of crystal structure of SnPn-based layered compounds. (a) Honeycomb network of SnPn conducting layer. (b) Crystal structure of ASnPn (hexagonal P63mc space group). (c) Crystal structure of ASn2Pn2 (trigonal R\(\bar{3}\)m space group). (d) Crystal structure of Sn4Pn3 (trigonal R3m space group). Here, A denotes the alkali metal or alkaline earth metal, and Pn denotes pnictogen. Black line represents the unit cell. For Sn4Pn3, there are two types of tin atom coordination in crystal structure. The Sn(1) and Sn(2) atoms are octahedrally coordinated by arsenic atoms only. The Sn(3) and Sn(4) atoms have a [3 + 3] coordination composed by three arsenic atoms from one side and three tin atoms beyond van der Waals (vdW) gap. To emphasize the similarity of SnPn layer with vdW gap, Sn(1) and Sn(2) atoms in Sn4Pn3 were drawn using different color from Sn(3) and Sn(4) atoms.

Herein, we report Na1−xSn2P2 as a new member of SnPn-based vdW-type superconductors with Tc = 2.0 K. Crystal structure analysis was performed using synchrotron powder X-ray diffraction (SPXRD). Superconducting properties were examined by the measurements of the electrical resistivity (ρ), magnetic susceptibility (χ) and the specific heat (C). Electronic structure was calculated on the basis of density functional theory (DFT).

Results and Discussion

Crystal structure analysis

Figure 2 shows the SPXRD pattern and the Rietveld fitting results for Na1−xSn2P2. Almost all the diffraction peaks can be assigned to those of the trigonal R\(\bar{3}\)m (No. 166) space group, indicating that Na1−xSn2P2 is isostructural to NaSn2As2. Although diffraction peaks attributable to elemental Na (10.1 wt%) was also observed, Na does not show superconductivity at least under ambient pressure. The results of the Rietveld analysis including the refined structural parameters were listed in Table 1. The lattice parameters were a = 3.8847(2) Å and c = 27.1766(13) Å. These are smaller than those of NaSn2As2 (a = 4.00409(10) Å and c = 27.5944(5) Å), mainly because of smaller ionic radius of P ions than As ions. The site occupancy of Na site was evaluated to be 0.926(18), suggesting that the sample in the present study contains Na deficiency. Note that energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy is not suitable to evaluate the chemical composition of the present sample because elemental Na is also observed as impurity phase.

Synchrotron powder X-ray diffraction (SPXRD) pattern (λ = 0.496916(1) Å) and the results of Rietveld refinement for Na1−xSn2P2. The circles and solid curve represent the observed and calculated patterns, respectively, and the difference between the two is shown at the bottom. The vertical marks indicate the calculated Bragg diffraction positions for Na1−xSn2P2 (upper) and Na (lower).

Superconducting properties

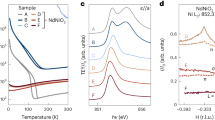

Figure 3a,b show the ρ − T plots for polycrystalline Na1−xSn2P2. Metallic behavior of the electrical resistivity was observed at temperatures above 10 K. A sharp drop in ρ was observed at 2.0 K, accompanied by zero resistivity at temperatures under 1.9 K, which indicates a transition to superconducting states. The transition temperature shifted toward lower temperatures with increasing applied magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 3c. It is noteworthy that the superconducting transition was distinctly broadened under magnetic field, probably because of the anisotropic upper critical field due to the two-dimensional layered crystal structure. The transition temperatures, Tc90% and Tczero, obtained from the temperature dependences of electrical resistivity under magnetic fields are shown in Fig. 3d. Here, Tc90% is defined as the temperature at which ρ is at 90% of the value at 3 K (normal state resistivity just above Tc), as indicated by a dashed line in Fig. 3c. The dependence of the upper critical field (Hc2) on temperature is still almost linear at T ≈ 0.5 K. Namely, the curve deviates from the Werthamer–Helfand–Hohemberg (WHH) model26. Here, the Pauli paramagnetic effect should be negligible because the Pauli limiting field is estimated as 1.84 × Tc = 3.7 T. We estimate μ0Hc2(0) as 1.5–1.6 T using linear extrapolation of Hc2 − Tc90% plot. The coherence length ξ was estimated to be ∼15 nm using the equation of ξ2 = Φ0/2πμ0Hc2, where Φ0 is magnetic flux quantum.

(a) Temperature (T) dependence of electrical resistivity (ρ) of Na1−xSn2P2. (b) ρ − T data below 6 K. (c) ρ − T data under magnetic fields up to 1.5 T with an increment of 0.1 T. Dashed line represents 90% of ρ at 3 K. (d) Magnetic field–temperature phase diagram of NaSn2P2. Dashed lines represent the least-squares fits of data plots.

Figure 4 shows T dependence of magnetization (M) for Na1−xSn2P2. Diamagnetic signals corresponding to superconducting transition was observed below 1.9 K, consistent with zero resistivity in ρ − T data. It should be noted that weak diamagnetic signal is also seen at around 3.7 K, probably due to trace Sn, although resistivity and specific heat (see below) do not show any anomaly at this temperature.

Figure 5a shows C/T as a function of T 2. A steep jump in C/T is observed at around 1.7 K, which is in reasonable agreement with the superconducting transition observed in the resistivity and magnetization. Because observed lattice specific heat for Na1−xSn2P2 in the normal state deviates from simple Debye model, the experimental data were fitted with a function including Einstein model:

where γ is the Sommerfeld coefficient, β is a phonon specific heat parameter, ΘE is a characteristic temperature of the low-energy Einstein mode, NA is the Avogadro constant, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and A is fitting parameter. The fit yields γ = 5.31 mJmol−1 K−2, β = 0.73 mJmol−1 K−4, A = 0.0095, and ΘE = 34 K. Considering the number of Einstein mode is 3ANA, the number of the acoustical mode is 3(n − A)NA, where n is the number of atoms per formula unit. Accordingly, the Debye temperature (ΘD) is represented as (12π4(n − A)NAkB/5β)1/3. We evaluated ΘD of Na1−xSn2P2 to be 237 K. As shown in Fig. 5b, the electronic specific heat jump at Tc (ΔCel) is 9.15 mJmol−1 K−2. From the obtained parameters, ΔCel/γTc is calculated as 1.0, which is slightly lower but in reasonable agreement with the value expected from the weak-coupling BCS approximation (ΔCel/γ Tc = 1.43). The electron–phonon coupling constant (λ) can be determined by Macmillan’s theory27, which gives

where μ* is defined as the Coulomb pseudopotential. Taking μ* = 0.13 gives λ = 0.40, which is consistent with weakly-coupled BCS superconductivity. Because the electron–phonon coupling constant of Na1−xSn2P2 is comparable to that of NaSn2As2 (λ = 0.44), higher Tc of Na1−xSn2P2 with respect to NaSn2As2 is likely due to increased density of states at the Fermi energy and/or the Debye temperature. Indeed, the γ and ΘD of NaSn2As2 were evaluated to be 3.97 mJ mol−1 K−2 and 205 K, respectively7. It should be noted that A = 0.0095 of Na1−xSn2P2 is distinctly lower than that of the compounds containing rattling atoms, such as β-pyrochlore AeOs2O6 (Ae = Rb, Cs), where A = 0.34–0.4728. The deviation of lattice specific heat from simple Debye model in Na1−xSn2P2 suggests the existence of low-energy phonon excitations with the flat dispersion in a limited region of the reciprocal space, rather than rattling motion of atoms. Indeed, calculated phonon dispersion of isostructural compound NaSn2As2 shows nonlinear characteristics resulting from overlapping between acoustic and optical modes, most likely due to the existence of lone-pair electrons16.

(a) Measured specific heat of Na1−xSn2P2 (red circles). Black line shows a fit to the experimental data above 2 K including electronic and phonon components (see text). Contributions from electrons and Debye phonon heat capacity (γT + βT 3) and low-energy Einstein mode (CEinstein) are denoted by green dotted line and blue dashed line, respectively. (b) Electronic specific heat of Na1−xSn2P2. Black solid line is used to estimate the specific heat jump (ΔCel) at Tc.

Figure 6 shows the calculated partial density of states of stoichiometric NaSn2Pn2 (Pn = P, As). Generally speaking, electronic structure of NaSn2P2 and NaSn2As2 is almost comparable. The energy bands from −12 eV to −10 eV and from −8 eV to −4 eV are mainly Pn s-orbitals and Sn s-orbitals in character, respectively. The bands that span from −4 eV to the Fermi energy are mainly Pn p-orbitals and Sn s/p-orbitals in character, confirming the electrical conduction is dominated by a SnPn covalent bonding network. The larger DOS of Pn p-orbitals than that of Sn p-orbitals in this energy region are consistent with the greater electronegativity of Pn. The energy bands mainly consisting of Sn s-orbitals are broadened, which is most likely due to the interlayer bonding. Na s-orbitals mainly locates from 1 eV to 3 eV, indicating the electron transfer from cationic Na layer to anionic SnPn layer. From the calculated electronic structure, it is evident that density of states at the Fermi energy is increased by Na deficiency, which reduces the Fermi energy. This is in agreement with higher Tc of Na1−xSn2P2 with respect to NaSn2As2.

Very recently, studies on temperature-dependent magnetic penetration depth29 and thermal conductivity30 show that superconductivity of NaSn2As2 is fully gapped s-wave state in the dirty limit, which should be consistent with above mentioned scenario. Detailed investigation on effect of off-stoichiometry in these compounds is currently under investigation.

Conclusion

In summary, we present the crystal structure, electronic structure, and superconductivity of novel material Na1−xSn2P2. Structural refinement using SPXRD shows that crystal structure of Na1−xSn2P2 belongs to the trigonal R\(\bar{3}\,\)m space group. Amount of x was estimated to be 0.074(18) from the Rietveld refinement. DFT calculations of the electronic structure confirm that the electrical conduction is dominated by a SnP covalent bonding network. Measurements of electrical resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and specific heat confirm the bulk nature of superconductivity with Tc = 2.0 K. On the basis of the structural and superconductivity characteristics of Na1−xSn2P2, which are similar to those of the structural analogue NaSn2As2, we consider that the SnPn layer can be a basic structure of layered superconductors. Because there are various structural analogues with SnPn-based conducting layers, our results indicate that SnPn-based layered compounds can be categorized into a novel family of vdW-type superconductors, providing a new platform for studies on physics and chemistry of low-dimensional superconductors.

Methods

Polycrystalline Na1−xSn2P2 was prepared by the solid-state reactions using Na3P, Sn (Kojundo Chemical, 99.99%), and P (Kojundo Chemical, 99.9999%) as starting materials. To obtain Na3P, Na (Sigma-Aldrichi, 99.9%) and P in a ratio of 3:1 were heated at 300 °C for 10 h in an evacuated quartz tube. A surface oxide layer of Na was mechanically cleaved before experiments. A stoichiometric mixture of Na3P:Sn:P = 1:3:2 was pressed into a pellet and heated at 400 °C for 20 h in an evacuated quartz tube. The obtained product was ground, mixed, pelletized, and heated again at 400 °C for 40 h in an evacuated quartz tube. The sample preparation procedures were conducted in an Ar-filled glovebox with a gas-purifier system or under vacuum. The obtained sample was stored in an Ar-filled glovebox because it is reactive in air and moist atmosphere.

The phase purity and the crystal structure of the samples were examined using synchrotron powder X-ray diffraction (SPXRD) performed at the BL02B2 beamline of the SPring-8 (proposal number of 2017B1283). The diffraction data was collected using a high-resolution one-dimensional semiconductor detector, multiple MYTHEN system31. The wavelength of the radiation beam was determined to be 0.496916(1) Å using a CeO2 standard. The crystal structure parameters were refined using the Rietveld method using the RIETAN-FP software32. The crystal structure was visualized using the VESTA software33.

Temperature (T) dependence of electrical resistivity (ρ) was measured using the four-terminal method with a physical property measurement system (PPMS; Quantum Design) equipped with a 3He-probe system. Magnetic susceptibility as a function of T was measured using a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer (Quantum Design MPMS-3) with an applied field of 10 Oe after both zero-field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC). The specific heat (C) as a function of T was measured using the relaxation method with PPMS.

Electronic structure calculations based on density functional theory were performed using the VASP code34,35. The exchange-correlation potential was treated within the generalized gradient approximation using the Perdew–Becke–Ernzerhof method36. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 9 × 9 × 3 Monkhorst–Pack grid37, and a cutoff of 350 eV was chosen for the plane-wave basis set. Spin-orbit coupling was included for the DFT calculation. Experimentally obtained structural parameters were employed for the calculation.

References

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba-La-Cu-O system. Z. Phys. B 64, 189 (1986).

Kamihara, Y. et al. Iron-based layered supercon- ductor La[O1−xFx]FeAs (x = 0.05–0.12) with T c = 26 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296 (2008).

Xi, X. et al. Strongly enhanced charge-density-wave order in monolayer NbSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 765–769 (2015).

Xi, X. et al. Ising pairing in superconducting NbSe2 atomic layers. Nat. Phys. 12, 139 (2016).

Tsen, A. W. et al. Nature of the quantum metal in a two-dimensional crystalline superconductor. Nat. Phys. 12, 208 (2016).

Y. Saito, T. Nojima, Y. Iwasa, Highly crystalline 2D superconductors. Nature Reviews Materials 2(1) (2017).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183 (2007).

Goto, Y. et al. SnAs-based layered superconductor NaSn2As2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86, 123701 (2017).

Arguilla, M. Q. et al. NaSn2As2: an exfoliatable layered van der Waals Zintl phase. ACS Nano 10, 9500 (2016).

Arguilla, M. Q. et al. EuSn2As2: an exfoliatable magnetic layered Zintl–Klemm phase. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2, 378 (2017).

Gibson, Q. D. et al. Three-dimensional Dirac semimetals: design principles and predictions of new materials. Phys. Rev. B 91, 205128 (2015).

Rong, L. et al. Electronic structure of SrSn2As2 near the topological critical point. Sci. Rep. 7, 6133–613 (2017).

Kovnir, K. et al. Sn4As3 revisited: solvothermal synthesis and crystal and electronic structure. J. Solid State Chem. 182, 630 (2009).

Olofsson, O. X-Ray investigations of the tin-phosphorus system. Acta Chem. Scand. 24, 1153 (1970).

Eisenmann, B. & Klein, J. Zintl-phasen mit schichtanionen: darstellung und kristallstrukturen der isotypen verbindungen SrSn2As2 und sowie eine einkristallstrukturbestimmung von KSnSb. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 598/599, 93 (1991).

Lin, Z. et al. Thermal conductivities in NaSnAs, NaSnP, and NaSn2As2: effect of double lone-pair electrons. Phys. Rev. B 95, 165201 (2017).

Arguilla, M. Q. et al. Optical properties and Raman-active phonon modes of two-dimensional honeycomb Zintl phases. J. Mater. Chem. C 5, 11259 (2017).

Eisenmann, B. & Rößler, U. Crystal structure of sodium phosphidostaimate (II), NaSnP. Zeitschrift für Krist. 213, 28 (1998).

Lii, K. H. & Haushalter, R. C. Puckered hexagonal nets in 2 ∞[Sn33As− 33] and 2 ∞[Sn33Sb− 33]. J. Solid State Chem. 67, 374 (1987).

Asbrand, M. & Eisenmann, B. Arsenidostannate mit arsen-analogen [SnAsI-schichten: darstellung und struktur von Na[Sn2As2], Na0.3Ca0.7[Sn2As2], Na0.4Sr0.6[Sn2As2], Na0.6Ba0.4[Sn2As2] und K0.3Sr0.7Sn2As2. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 621, 576 (1995).

Schmidt, P. C. et al. Electronic structure of the layered compounds K[SnSb], K[SnAs] and Sr [Sn2As2]. J. Solid State Chem. 97, 93 (1992).

Asbrand, M. et al. Bonding in some Zintl phases: a study by tin-119 Mossbauer spectroscopy. J. Solid State Chem. 118, 397 (1995).

Geller, S. & Hull, G. W. Superconductivity of intermetallic compounds with NaCl-type and related structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 127 (1964).

Maareen, M. H. On the superconductivity, carrier concentration and the ionic model of Sn4P3 and Sn4As3. Phys. Lett. 29A, 293 (1969).

Huang, S. et al. First-Principles Study of the Thermoelectric Properties of the Zintl Compound KSnSb. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 122(8), 4217–4223 (2018).

Werthamer, N. R., Helfand, E. & Hohenberg, P. C. Temperature and purity dependence of the Superconducting critical field, Hc2. III. electron spin and spin-orbit effects. Phys. Rev. 147, 295 (1966).

McMillan, W. L. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors. Phys. Rev. 167, 331 (1968).

Nagao, Y. et al. Rattling-induced superconductivity in the β-pyrochlore oxides AOs2O6. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 064702 (2009).

Ishihara, K et al. Evidence for s-wave pairing with atomic scale disorder in the van der Waals superconductor NaSn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 98, 020503 (2018).

Cheng, E. J. et al. Nodeless superconductivity in the SnAs-based van der Waals type superconductor NaSn2As2. arXiv:1806.1141 (2018).

Kawaguchi, S. et al. High-throughput powder diffraction measurement system consisting of multiple MYTHEN detectors at beamline BL02B2 of SPring-8. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 85111 (2017).

Izumi, F. & Momma, K. Three-dimensional visualization in powder diffraction. Solid State Phenom. 130, 15 (2007).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 653 (2008).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Higashinaka and O. Miura for their experimental support. We thank K. Kuroki, H. Usui, T. Shibauchi, Y. Mizukami, and K. Ishihara for their fruitful discussion. This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos 15H05886, 15H05884, 16H04493, 17K19058, 16K17944, and 15H03693) and Iketani Science and Technology Foundation (No. 0301042-A), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. performed sample preparation and characterization. Y.M. supervised the experimental work. Y.G., A.M., C.M., Y.K. and Y.M. conducted SXRD measurements. Y.G., T.D.M., Y.A. performed physical properties measurements. Y.G. performed DFT calculation. Y.G. and Y.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goto, Y., Miura, A., Moriyoshi, C. et al. Na1−xSn2P2 as a new member of van der Waals-type layered tin pnictide superconductors. Sci Rep 8, 12852 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31295-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31295-8

- Springer Nature Limited