Abstract

The kakapo is a critically endangered, herbivorous parrot endemic to New Zealand. The kakapo hindgut hosts a dense microbial community of low taxonomic diversity, typically dominated by Escherichia fergusonii, and has proven to be a remarkably stable ecosystem, displaying little variation in core membership over years of study. To elucidate mechanisms underlying this robustness, we performed 16S rRNA gene-based co-occurrence network analysis to identify potential interactions between E. fergusonii and the wider bacterial community. Genomic and metagenomic sequencing were employed to facilitate interpretation of potential interactions observed in the network. E. fergusonii maintained very few correlations with other members of the microbiota, and isolates possessed genes for the generation of energy from a wide range of carbohydrate sources, including plant fibres such as cellulose. We surmise that this dominant microorganism is abundant not due to ecological interaction with other members of the microbiota, but its ability to metabolise a wide range of nutrients in the gut. This research represents the first concerted effort to understand the functional roles of the kakapo microbiota, and leverages metagenomic data to contextualise co-occurrence patterns. By combining these two techniques we provide a means for studying the diversity-stability hypothesis in the context of bacterial ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) is an endemic New Zealand parrot, known for its unusual diet, nocturnal behaviour and lack of flight. The kakapo is classified as ‘critically endangered’ with a current population of approximately 150 individuals confined to predator-free islands off the coast of New Zealand. The diet of the kakapo is something of a peculiarity – although kakapo are nominally herbivorous they do not ingest large volumes of plant material, instead preferring to crush plant fibres in their beaks, extracting the juices and discarding the remainder1,2. The diet of the kakapo generally revolves around shoots and leaves, with the exception of the infrequent breeding seasons during which kakapo feed extensively on the fruit of the native rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum). Breeding in kakapo is entrained to the mast fruiting of this tree, possibly owing to its high concentration of calcium and vitamin D3, but even during this period of low-fibre feeding cellulose is the most abundant carbohydrate in the kakapo crop4.

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract-associated bacteria have been of interest for over half a century5 and have been linked to improved energy harvest from food sources6,7,8, vitamin and nutrient synthesis9,10,11, and gut development12,13. Diet is a powerful factor in shaping the gut microbiota14,15,16 as it governs the nutrients available to that community. Even when the host feeds on a single food source a diverse range of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins are introduced to the gut. The resident microbiota feed on these nutrients with individual species, or interacting webs of species, utilising different nutrients from the ingesta17. In vertebrates with and without anatomical adaptation to herbivory (e.g. ruminants and panda, respectively) the resident microbiota plays a critical role in the depolymerisation of cellulose and hemicellulose into sugars that are accessible to the host8,18,19.

Microbial degradation of cellulose is likely to occur in the kakapo as well, but the functional role of kakapo-associated microbes currently remains unexplored. With the exception of two studies of specific pathogens20,21, the kakapo microbiota has only recently been investigated, with analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences revealing low-diversity, but distinct, bacterial communities in the crop (foregut) and hindgut22. Unlike most vertebrate gut communities, the kakapo microbiota is dominated by Gammaproteobacteria and Firmicutes, with Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes observed sporadically, and at low abundances in most individuals23,24,25. Interestingly, the gut microbiota is typically dominated by a single bacterial species, identified through cultivation as Escherichia fergusonii26. Monitoring over a number of years has revealed that the kakapo microbiota is surprisingly robust23,25, although the mechanism(s) underlying such stability and how members of the microbiota interact within the gut remain unexamined.

Metagenomic analysis of microbial data sets has allowed for unparalleled insights into the functional ability of the gut microbiota and represents a powerful tool for discovering the role of the microbiota within an animal’s gut. Metagenomic data are frequently interpreted as though all bacteria are capable of interacting; however, factors such as spatial separation, physicochemical characteristics and even community turnover create barriers and local niches that can limit the ability of one bacterium to interact with another. Confirming suspected interactions requires intense, often highly selective, study that negates the benefits offered by high-throughput techniques. Co-occurrence networks of microbial communities represent a means to bridge such limitations, allowing researchers to identify population subsets within a microbiota that may be interacting in either a beneficial or antagonistic manner. In this approach, individual species (or operational taxonomic units – OTUs) are represented by nodes in a web, connected by predicted interactions with other species27,28,29. This allows the development of more specific research questions as well as an objective basis for partitioning large data sets into biologically relevant subsets, and provides a means to identify keystone species30. Network analysis also provides other metrics to analyse the community through measures such as the degree of community fragmentation31.

The relationship between community diversity and stability is a long-studied issue within ecology32,33. At its core, the hypothesis states that a more diverse community of co-occurring organisms is more likely able to compensate for environmental fluctuations, and maintain its functional capacity over long periods32. While diversity may therefore be considered a proxy for stability, it is not necessarily the causal agent and may instead result as a consequence of the ecological forces which underpin stability34,35,36. The kakapo gut microbiota often appears to be a near monoculture of Escherichia, yet this community is undoubtedly resilient to both variation through time and anthropogenic interference23,25. While Escherichia-like sequences are frequently observed in the microbiota of other birds, including parrots37,38,39,40,41,42,43, the uneven distribution of microbes in the kakapo hindgut appears unique. In order to elucidate mechanisms underlying this observation, we performed co-occurrence network analysis on 16S rRNA gene amplicon data in an attempt to characterise potential ecological interactions of Escherichia within the gut microbiota. We further employed genomic sequencing of cultured representatives of dominant members of the microbiota and shotgun metagenome sequencing of the uncultivated microbiome to identify a functional basis for the findings of the network analysis.

Materials and Methods

Amplicon sequencing and analysis

Fresh faecal samples were obtained from three adult and three juvenile kakapo and DNA was extracted using a previously reported bead-beating technique22. PCR was performed using the 533 F (5′-GTG CCA GCA GCY GCG GTM A-3′) and 907 R (5′-CCG TCA ATT MMY TTG AGT TT-3′) Bacteria-targeting primers, to amplify an approximately 350 bp region of the 16S rRNA gene sequence. Cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturing step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 20 touchdown cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s with a 0.5 °C decrease in annealing temperature per cycle. Touchdown was followed by 10 additional cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s followed by a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min23. PCR products were purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP kit (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Brea CA, United States) and amplicon size examined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. DNA concentration was quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA) according to manufacturer instructions. DNA was pooled at equimolar concentrations and pyrosequencing was performed by Macrogen Inc (Seoul, South Korea) using the GS-FLX Titanium platform.

A subset of 16S rRNA gene amplicon data from three time points of a previous study of the gut microbiota of 10 juvenile and 10 adult kakapo were utilized in this study23 (Table S1). Samples from the captivity cohort of the original study were removed from the data set to remove the confounding effect of antibiotic treatment on community dynamics. This selection criterion resulted in a total of 36 amplicon samples from previous data and six additional amplicon samples amplified from the samples used for metagenome sequencing. Raw data were processed using mothur (version 1.36.1)44 following the standard operating procedure for pyrosequencing data. Flowgrams were trimmed to equal length and denoised, then the resulting sequences were trimmed of barcodes and primer sequences. Trimmed sequences were then aligned to the SILVA reference alignment (version 119) and short sequences, together with those containing ambiguous base calls or homopolymer runs greater than 8 nucleotides, removed. The aligned sequences were then end-trimmed and chimeric sequences identified using UCHIME45 were removed from the data set. The remaining high-quality sequences were classified against an alignment-trimmed SILVA small subunit database (version 119)46,47 using the naïve Bayesian method48. Sequences identified as archaeal, eukaryotic, chloroplast, or mitochondria were removed, as were sequences that could not be classified to at least phylum level. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered at 99% sequence identity from the remaining sequences and the taxonomic affiliation of each OTU taken as the consensus taxonomy of the individual sequences contributing to that cluster. OTUs present in fewer than five samples were removed from the OTU table, which was then randomly subsampled to a depth of 2,000 sequences per sample. The community structure of the OTU data set was visualised using non-metric multidimensional scaling of a Bray-Curtis distance matrix calculated from the OTU table using the vegan package in R49,50.

Amplicon network analysis

Correlation scores between pairs of OTUs were calculated in SparCC using 20 refining iterations, after which statistical significance was assigned to each correlation using a pseudo-p value approximation with 1,000 permutations51 then analysed in the R software environment using the igraph package49,52. OTU correlations were encoded as a graph whereby OTUs (nodes) were joined via unweighted edges if their correlation coefficient was greater than or equal to 0.3 and statistically significant following a Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing (FDR ≤ 0.05). Although some analyses have constructed a unified graph of all interactions53,54,55, we opted to restrict our data to positive correlations only. This approach was chosen as the ecological interpretation and consequence of positive/negative correlations differ, and the commonly utilised network statistics do not account for polarity of an interaction. The network statistic transitivity (also known as clustering coefficient) was calculated for the complete network and interpreted in the context of a clustering ratio, comparing the clustering density of the kakapo graph to randomly constructed graphs with the same number of nodes and edges. As the topology of graphs, and their network statistics, can vary greatly with random permutation (Fig. S1), 1,000 random graphs were constructed to create a null distribution of transitivity scores, and the median value used to calculate the clustering ratio of the kakapo network. Node-specific statistics degree and betweenness were calculated for each OTU using the methods and definitions described by Williams et al.53. The resulting network was visualised using Cytoscape56 and figures prepared for publication using Inkscape.

Extraction and sequencing of genomic and metagenomic DNA

Eight bacterial isolates, previously obtained from kakapo faeces (Table S2)26, were grown to stationary phase and genomic DNA extracted using a standard enzymatic digest protocol with minor modifications57. Cells were suspended in TE buffer and 740 µL of suspension transferred to a fresh 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Forty microlitres of lysozyme (100 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO, USA), 40 µL 10% SDS and 16 µL proteinase K (10 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO, USA) were added, and tubes were incubated overnight at 37 °C with gentle mixing. Following cell lysis, 100 µL NaCl (5 M) and 100 µL CTAB/NaCl mixture (described in original protocol) were added and samples further incubated at 65 °C for 10 min. Five hundred microlitres of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added to each sample and tubes were mixed by inversion then centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm. One millilitre of supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and the process repeated with 500 µL phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). Supernatant (~1 mL) was transferred to a fresh 2 mL microcentrifuge tube to which 0.6 vol isopropanol and 0.1 vol sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2) were added. Samples were mixed by inversion and incubated at room temperature for 1 h then centrifuged at 16,000 g at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was removed and the resulting pellet washed twice with ice-cold 70% ethanol. Samples were air dried then resuspended in 20 µL TE buffer with RNase A (Qiagen, Germantown, MS, USA), incubated for 20 min at 37 °C, then finally stored at −20 °C. DNA concentration was calculated using a QuBit Quant-iT DNA high-sensitivity assay and DNA was electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel to assess shearing.

For metagenomic analysis, faeces were fractionated by suspending one gram of faecal material in 5 mL PBS and vortexing for 2 min then centrifuging at 800 g for 2 min58. The upper fraction was collected and centrifuged at 7,500 g for 7 min, then supernatant removed and pelleted biomass washed twice with 1 mL PBS. DNA extraction was performed as above with a single modification: following addition of CTAB/NaCl, samples were incubated at 94 °C for 30 min, then briefly cooled on ice. For both genomic and metagenomic samples, library preparation and sequencing were performed by New Zealand Genomics Ltd. Raw DNA was prepared using the Nextera XT kit and samples pooled for sequencing. All 14 samples were sequenced together in three separate sequencing runs, to allow for adjustment of template ratios between runs to correct over-/under-represented samples. Sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq with 2 × 250 bp paired-end reads.

Genomic and metagenomic analysis

Raw genomic reads were filtered and assembled using the PAGIT toolkit59. Briefly, reads were quality trimmed using sickle60 in paired-end mode, with a quality threshold of 20 and minimum read length of 50 bp. Genomes were then assembled de novo using velvet61, with kmer sizes determined manually for each genome. Gap closing was then performed using IMAGE62, and error correction with ICORN63 with default settings. Metagenomic sequences from all samples were processed using the same workflow, but pooled for assembly in MetaVelvet64. Gene prediction for both genomes and the metagenome was performed using Prodigal65 and predicted protein sequences annotated using BLAST against the NCBI non-redundant protein database requiring a minimum sequence identity ≥50%, and an e-value of ≤ 1e-5. For genomic comparison, we downloaded the genomes of 177 Enterobacteriaceae type species, including Escherichia coli, E. fergusonii, and E. albertii, from the NCBI genome database and annotated these using the same approach. Functional pathway analysis was performed using MEGAN66. Isolate genomes were further annotated against the CAZy database using the dbCAN web server67,68. For phylogenetic inference of the beta-1,4-endoglucan hydrolase orthologues, protein sequences were aligned using MAFFT with the high-sensitivity (L-INS-i) algorithm69,70. The alignment was then trimmed with TrimAl71 and phylogenetic inference performed with RAxML72 under the Le and Gascuel model of amino acid substitution73 and 100 bootstrap resamplings to assess node support.

Per-sample gene abundances were calculated by mapping the quality filtered, unassembled sequences from each sample to the assembled contigs using bowtie274. Reads mapped to each contig were then normalised by length to account for longer contigs receiving a larger proportion of reads mapping. Annotated genes within the metagenome were separated based on the taxonomic origin of sequences, using the least-common ancestor method in MEGAN to identify and extract bins of metagenomic sequence data. All novel sequence data were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA381379.

Results and Discussion

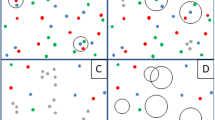

To ensure that samples selected for metagenome sequencing were representative of the kakapo microbiome, we compared 16S rRNA gene amplicon data from each candidate metagenome sample to previously sequenced kakapo amplicon data. No strong influence of environmental or age-related factors was observed in the amplicon data at either the taxonomic or OTU level (Fig. 1, Fig. S2), and samples intended for metagenome sequencing represented the Proteobacteria-rich, Firmicutes-rich, and intermediate community states (Fig. 1). With no clear environmental or age-related factors separating the microbiota of kakapo samples, and hence biasing findings, we examined the data set for evidence of interactions between bacteria in the microbiota. Rarefaction analysis was performed to verify that subsampling the OTU table to 2,000 sequences per sample provided sufficiently saturated counts (Fig. S3). OTUs observed in fewer than five samples were removed from the data set, resulting in a median Jaccard similarity of 0.27 between samples, consistent with the recommendations of Berry and Widder30. Correlations between pairs of OTUs were calculated using SparCC, and a network graph constructed from OTUs (nodes) if their correlations (edges) were ≥0.3 and statistically significant (FDR ≤ 0.05). The degree of clustering in the resulting network was compared to a null distribution of randomly constructed networks of equal numbers of nodes and edges. The cluster ratio of the kakapo network was 4.6, indicating approximately four-fold greater clustering than could be expected by chance in an equally dense network. This finding is biologically relevant as it indicates that bacterial OTUs within the microbiota are forming small, highly interacting sub-populations rather than existing in a more generalised system (for example, Fig. S1). Overall, this suggests that rather than a single metacommunity, the kakapo microbiota acts as a set of smaller components that are nominally independent of each other.

Phylum-level distribution of sequences in the amplicon data. Taxonomic abundance data were summarised at the phylum level and clustered using furthest-neighbour hierarchical clustering. Clustering was performed using the full phylum-level profile, with the following phyla aggregated to ‘Other’ for ease of viewing: Acidobacteria, Armatimonadetes, Chloroflexi, Fusobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Planctomycetes, Saccharibacteria, Spirochaetes, Verrucomicrobia, WPS-1, WPS-2, and unclassified. Time points refer to sampling strategy in Table S1. Samples selected for metagenome sequencing and amplified with amplicon sequence are marked in red. ‘Metagenome’ column refers to the taxonomic overview of the assembled and annotated metagenome.

Previous research into the kakapo microbiota has identified two bacterial species, Escherichia fergusonii and Streptococcus gallolyticus, as present in all kakapo samples22,23,26, although more recent analysis indicates that the core kakapo microbiome consists of only E. fergusonii25. Regardless of the exact membership of the core microbiota, we were interested in identifying microbes that may be involved in mutualistic interactions with these two organisms. Defining OTUs at 99% sequence identity yielded three OTUs belonging to the gammaproteobacterial genus Escherichia (Escherichia-OTUs). The most abundant of these OTUs (29.4% of reads across all samples) was not associated with any other OTUs in the network (Fig. 2). Two additional Escherichia-OTUs (totalling 10.0% of reads) were correlated with each other and OTUs belonging to the Gammaproteobacteria which could not be classified below family level (Enterobacteriaceae-OTUs). Consistent with previous research a single Streptococcus-OTU (20.3% of reads) was detected and correlated with an OTU belonging to the genus Clostridium (Fig. 2).

Interaction networks of the kakapo microbiota. 16S rRNA gene-based correlation network of the kakapo microbiota, displaying statistically significant interactions with a correlation coefficient of ≥0.3. Node size is scaled based on the overall abundance of each OTU in the microbiota. ‘Enterobacteriaceae’ nodes represent OTUs that could not be classified beyond the family level, and does not include sequences classified as Escherichia. OTU labels of Escherichia nodes refer to OTU identifiers in Table 1.

Network analysis provides several metrics which can be used to indicate the importance of particular species to the wider community30,75 and owing to their frequent occurrence in the kakapo microbiota we aimed to ascertain the ecological importance of the Escherichia- and Streptococcus-OTUs in the microbiota. We scored all OTUs using the degree (number of connecting edges, normalised to graph size) and betweenness (number of shortest connecting paths that travel through an OTU) statistics then ranked each OTU by score. Consistent with their low incidence of co-occurrence in the visualised graph, Escherichia-OTUs generally did not score highly under either metric (Table 1). The apparent lack of correlations between these core OTUs may suggest that Escherichia-OTUs thrive in the gut due to their metabolic capacity that affords them the luxury of non-reliance on syntrophic interactions with other gut bacteria.

The kakapo gut microbiota is stable through time and resilient to changes in diet and anthropogenic perturbations, yet is one of the lowest diversity avian microbiotas known76. Bacteria of the genus Escherichia are often detected in the guts of avians37,38,39,40,41,42,43 but they have not been reported at the abundances found in the kakapo. A long-standing hypothesis to explain the ubiquity of Escherichia in the gut of kakapo was that it was a consequence of supplemental feeding and human intervention. However, a recent analysis of kakapo which have never received supplemental feeding does not support this hypothesis25. While it is important to recognise that the lack of observed correlation does not exclude the possibility of ecological interactions between Escherichia-OTUs and other microbes in the kakapo gut, this finding does provide evidence that such an interaction would not be a strong effect. In order to contextualise these observations we sequenced the genomes of six E. fergusonii and two S. gallolyticus isolates cultivated from the kakapo gut. We further supplemented these data with shotgun metagenomic sequencing to obtain functional data for bacteria which have previously evaded culture.

Quality filtering of genomic and metagenomic sequences resulted in between 1.3 and 2.9 million reads per bacterial isolate, and approximately 17.9 million paired reads from metagenome samples (Table S3). Assembly of isolate genomes yielded draft genomes with sizes and predicted gene counts appropriate for their respective organisms (Table S3). Gene prediction and annotation of the kakapo metagenome yielded a total of 257,679 predicted genes, of which 90.3% (233,154) were bacterial. Only 14 genes of archaeal origin were detected, consistent with our previous finding that archaea are extremely rare or absent from the kakapo gut22. The remaining genes were of eukaryotic (avian and fungal, 0.9%) or viral (0.03%) origin, or were unable to be annotated (8.6%). The taxonomic profile of the bacterial metagenome was consistent with the results of amplicon sequencing (Fig. 1), dominated by genomic material belonging to Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, with a smaller number of Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes genes detected. The majority of sequences were identified as belonging to the KEGG pathways associated with carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid turnover (Table 2).

The kakapo diet is low in starch2,4,77 and the most abundant carbohydrate sources in the diet of kakapo are cellulose and other fibrous material. Depolymerisation of plant fibres such as cellulose, hemicellulose and xylan is a difficult biological process and is frequently outsourced to the gut microbiota19,78,79. Cellulose degradation typically occurs in a two-step method whereby cellulose polymers are fragmented into shorter cellobiose oligomers, which are in turn hydrolysed to glucose by cellobiases. The initial step of depolymerising cellulose to cellobiose in the kakapo microbiome was attributed exclusively to members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (including Escherichia) and was observed in all E. fergusonii genomes. Amongst the isolate genomes, however, the abundance of glucoside hydrolases was not sufficiently high (0.96–1.16% of genome) to consider these isolates cellulolytic specialists80. Genes responsible for the subsequent liberation of glucose from cellobiose were present in many other bacterial lineages including the genera Streptococcus and Clostridium (Table 3). It appears that while these lineages are capable of metabolising cellulose by-products, they are incapable of digesting long-chain cellulose. In a similar vein, we observed genes coding for the utilisation of xylose within the Escherichia genomes and metagenome, but no apparent ability to perform the initial depolymerisation of xylan. Genes responsible for the depolymerisation of xylan were present in the metagenome, belonging exclusively to non-Escherichia members of the Enterobacteriaceae (Table 3), providing a potential mechanism explaining the correlation between Escherichia- and Enterobacteriaceae-OTUs (Fig. 2). Genes related to the utilisation of other plant polysaccharides such as sucrose and maltose were observed in the E. fergusonii genomes and the Enterobacteriaceae-, Streptococcus-, and Clostridium-attributed proteins of the metagenome. Amylases were observed in the E. fergusonii and S. gallolyticus genomes, as well as all four groups of interest in the metagenome.

E. fergusonii, or OTUs suspected to represent this species, are frequently the most abundant lineage found in the kakapo gut and the species has retained this status over six years of molecular surveying22,25. The kakapo microbiota is remarkably stable and even after antibiotic stress is able to recover to the ‘normal’ state within weeks23. Our data represent the first metagenomic insights into the kakapo microbiome and provide a hypothesis to explain the mechanism by which E. fergusonii is maintained despite its apparent weak interaction with the remainder of the microbiota. Amongst the microbial lineages investigated, E. fergusonii alone has the genomic potential to utilise all forms of carbohydrate encountered by the kakapo, independent of mutualistic interactions with other members of the microbiota. For example, when the kakapo is not receiving supplemental feeding E. fergusonii appears able to metabolise cellulose but if the kakapo gains access to supplemental feed, E. fergusonii possesses the genomic capacity to utilize the starch that this food source provides. By contrast, other members of the microbiota are only capable of using a subset of the available resources and will presumably go through periods of starvation during which they will be unable to reproduce. Analysis of the genomic content of isolate genomes did not reveal significant difference between kakapo isolates and the previously cultivated Enterobacteriaceae type material (Fig. S4). The low abundance of glucoside hydrolase enzymes in the genomes, and the standard vertical inheritance of beta-1,4-endoglucan hydrolase (Fig. S5), further indicate that the E. fergusonii genomes have not evolved novel celluloytic functionality to colonize the kakapo gut. Some Escherichia-OTUs were predicted to interact with Enterobacteriaceae-OTUs, which we hypothesise possess the ability to depolymerise xylan based on metagenomic data. If correct, this interaction provides an additional avenue for the metabolism of E. fergusonii via xylose by-products.

Based on its predicted ability to metabolise a wide range of plant sugars, E. fergusonii appears to be extremely well suited to the kakapo gut as a metabolic generalist, able to utilise both natural and supplemental energy sources. In contrast, the other microbes such as S. gallolyticus appear able to make use of only a fraction of the available carbohydrate sources. Members of the Firmicutes such as Clostridium and Streptococcus may be able to make use of partially digested plant fibre produced by E. fergusonii or other Enterobacteriaceae, although our data suggest that this would not be a consistent occurrence. Even when discounting the numerical abundance of OTUs and presence/absence measures are considered, the kakapo microbiota is stable through time despite its low phylogenetic diversity24,25. We attribute this apparent stability to the considerable diversity of carbohydrate metabolism pathways within the kakapo microbiota, primarily attributed to E. fergusonii and the limited diet of the kakapo. These data demonstrate that taxonomic diversity alone does not accurately reflect the ‘true’ functional diversity within an ecosystem, and that the diversity-stability interaction should not be thought of solely in terms of taxonomic diversity.

It is possible that the ubiquity of E. fergusonii in the kakapo microbiota is the result of an opportunistic colonization event, where it has supplanted the original kakapo microbiota, or that this bacterium has only risen to prominence in response to the supplemental feeding practice. Such an event would be consistent with the lack of differentiation in isolate genomes that would suggest adaptation to the kakapo hindgut. We do not consider this scenario likely, however, as the microbiota from kakapo that have never received supplemental feeding are also rich in E. fergusonii-like OTUs25. Furthermore, such a hypothesis would stand in strict opposition to the observation that microbiomes tend to evolve through time with their host lineage.

We have performed an in-depth examination of the kakapo gut microbiota with the aim of understanding the ecological interactions among key gut microbes. Insights into potential mutualisms occurring within this habitat were gained using correlation network analysis, then further explored through genome and metagenome sequencing. Our findings suggest that E. fergusonii strains have the metabolic capacity to persist and grow in the kakapo gut. Futhermore, the lack of a robust and reproducible correlations with other members of the gut microbiome suggests that this growth occurs without reliance upon syntrophic partners. We attribute this observation to functional flexibility within the Escherichia genome. These data are important not only for their relevance to understanding the kakapo microbiota, but they provide evidence that taxonomic diversity is not the only means through which ecological stability can be achieved. This finding is an important consideration for understanding microbial environments which are known for, and often discussed in terms of, their phylogenetic diversity. More specifically, our data provide a basis for beginning to understand the forces which govern the kakapo microbiome and will provide a framework for future investigation.

References

Oliver, W. R. B. New Zealand Birds. New Zealand Birds (A. H. & A. W. Reed: Wellington, New Zealand, 1955).

Horrocks, M. et al. Plant microfossil analysis of coprolites of the critically endangered kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) parrot from New Zealand. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 149, 229–245 (2008).

von Hurst, P. R., Moorhouse, R. J. & Raubenheimer, D. Preferred natural food of breeding Kakapo is a high value source of calcium and vitamin D. J. Ster. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 164, 177–179 (2016).

Cottam, Y., Merton, D. V. & Hendriks, W. Nutrient composition of the diet of parent-raised kakapo nestlings. Notornis 53, 90–99 (2006).

Dubos, R. & Schaedle, R. W. The digestive tract as an ecosystem. Am. J. Med. Sci. 248, 267–272 (1964).

Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444, 1027–1031 (2006).

Stanley, D. et al. Intestinal microbiota associated with differential feed conversion efficiency in chickens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 96, 1361–1369 (2012).

Shabat, S. K. B et al. Specific microbiome-dependent mechanisms underlie the energy harvest efficiency of ruminants. ISME J. 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.62 (2016).

Uphill, P. F., Jacob, F. & Lall, P. Vitamin B12 production by the gastro-intestinal microflora of baboons fed either a Vitamin B12 deficient diet or a diet supplemented with vitamin B12. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 43, 333–344 (1977).

Hill, M. J. Intestinal flora and endogenous vitamin synthesis. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 6, S43–S45 (1997).

LeBlanc, J. G. et al. Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: A gut microbiota perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24, 160–168 (2013).

Stappenbeck, T. S., Hooper, L. V. & Gordon, J. I. Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15451–15455 (2002).

Björkholm, B. et al. Intestinal microbiota regulate xenobiotic metabolism in the liver. PLoS One 4, e6958 (2009).

Muegge, B. D. et al. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science 332, 970–974 (2011).

Ley, R. E. et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320, 1647–1651 (2008).

David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014).

Pereira, F. C. & Berry, D. Microbial nutrient niches in the gut. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 1366–1378 (2017).

Yoon, S. S., Kim, E. K. & Lee, W. J. Functional genomic and metagenomic approaches to understanding gut microbiota-animal mutualism. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 24, 38–46 (2015).

Zhu, L., Wu, Q., Dai, J., Zhang, S. & Wei, F. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17714–17719 (2011).

Brangenberg, N. et al. Absence of Salmonella and Campylobacter species in fecal and cloacal swab samples from kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) on Codfish Island, New Zealand. J. Avian Med. Surg. 17, 203–205 (2003).

Gartrell, B. D. et al. Erysipelas in the critically endangered kakapo (Strigops habroptilus). Avian Pathol. 34, 383–387 (2005).

Waite, D. W., Deines, P. & Taylor, M. W. Gut microbiome of the critically endangered New Zealand parrot, the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus). PLoS One 7, e35803 (2012).

Waite, D. W., Eason, D. K. & Taylor, M. W. Influence of hand rearing and bird age on the fecal microbiota of the critically endangered kakapo. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 4650–4658 (2014).

Waite, D. W. & Taylor, M. W. Characterizing the avian gut microbiota: Membership, driving influences, and potential function. Front. Microbiol. 5 (2014).

Perry, E. K., Digby, A. & Taylor, M. The low-diversity fecal microbiota of the critically endangered kākāpō is robust to anthropogenic dietary and geographic influences. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2033 (2017).

Waite, D. W., Deines, P. & Taylor, M. W. Quantifying the impact of storage procedures for faecal bacteriotherapy in the critically endangered New Zealand parrot, the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus). Zoo Biol. 32, 620–625 (2013).

Bascompte, J. Disentangling the web of life. Science 325, 416–419 (2009).

Thébault, E. & Fontaine, C. Stability of ecological communities and the architecture of mutualistic and trophic networks. Science 329, 853–856 (2010).

Ulanowicz, R. E. Quantitative methods for ecological network analysis. Comput. Biol. Chem. 28, 321–339 (2004).

Berry, D. & Widder, S. Deciphering microbial interactions and detecting keystone species with co-occurrence networks. Front. Microbiol. 5, 219 (2014).

Widder, S. et al. Fluvial network organization imprints on microbial co-occurrence networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 12799–12804 (2014).

McNaughton, S. J. Diversity and stability of ecological communities: A comment on the role of empiricism in ecology. Am. Nat. 111, 515–525 (1977).

Tilman, D. The ecological consequences of changes in biodiversity: A search for general principles. in. Ecology 80, 1455–1474 (1999).

McCann, K. S. The diversity-stability debate. Nature 405, 228–233 (2000).

Ives, A. R. & Carpenter, S. R. Stability and diversity of ecosystems. Science. 317, 58–62 (2007).

Shade, A. Diversity is the question, not the answer. ISME J. 11, 1–6 (2017).

Pacheco, M. A., García-Amado, M. A., Bosque, C. & Domínguez-Bello, M. G. Bacteria in the crop of the seed-eating Green-rumped parrotlet. Condor 105, 139–143 (2003).

Xenoulis, P. G. et al. Molecular characterization of the cloacal microbiota of wild and captive parrots. Vet. Microbiol. 146, 320–325 (2010).

Dewar, M. L. et al. Influence of fasting during moult on the faecal microbiota of penguins. PLoS One 9, e99996 (2014).

Lewis, W. B., Moore, F. R. & Wang, S. Characterization of the gut microbiota of migratory passerines during stopover along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. J. Avian Biol. 47, 659–668 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. Distinctive gut microbial community structure in both the wild and farmed Swan goose (Anser cygnoides). J. Basic Microbiol. 56, 1299–1307 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Simon, S. E., Johnson, J. A. & Allen, M. S. Spatial microbial composition along the gastrointestinal tract of captive Attwater’s prairie chicken. Microb. Ecol. 73, 9966–9771 (2016).

Zhao, G., Zhou, L., Dong, Y., Cheng, Y. & Song, Y. The gut microbiome of hooded cranes (Grus monacha) wintering at Shengjin Lake, China. Microbiologyopen 6, e00447 (2017).

Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: Open - Source, Platform - Independent, Community - Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 (2009).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011).

Werner, J. J. et al. Impact of training sets on classification of high-throughput bacterial 16 s rRNA gene surveys. ISME J. 6, 94–103 (2012).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna Austria (2016).

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F., Kindt, R., Legendre, P. & O’Hara, R. Vegan: community ecology package. R package 2.3-3 Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packa, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412971874.n145 (2016).

Friedman, J. & Alm, E. J. Inferring correlation networks from genomic survey data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002687 (2012).

Csárdi, G. & Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal Complex Syst. 1695, 1695 (2006).

Williams, R. J., Howe, A. & Hofmockel, K. S. Demonstrating microbial co-occurrence pattern analyses within and between ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 5, 358 (2014).

Roggenbuck, M. et al. The microbiome of New World vultures. Nat. Commun. 5, 5498 (2014).

Marino, S., Baxter, N. T., Huffnagle, G. B., Petrosino, J. F. & Schloss, P. D. Mathematical modeling of primary succession of murine intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 439–444 (2014).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software Environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Feil, W. S., Feil, H. & Copeland, A. Bacterial genomic DNA isolation using CTAB. 2013 (2012).

Peris-Bondia, F., Latorre, A., Artacho, A., Moya, A. & D’Auria, G. The active human gut microbiota differs from the total microbiota. PLoS One 6, e22448 (2011).

Swain, M. T. et al. A post-assembly genome-improvement toolkit (PAGIT) to obtain annotated genomes from contigs. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1260–1284 (2012).

Joshi, N. & Fass, J. Sickle: A sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files (Version 1.33) [Software]. Available at https://github.com/najoshi/sickle (2011).

Zerbino, D. R. & Birney, E. Velvet: Algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829 (2008).

Tsai, I. J., Otto, T. D. & Berriman, M. Improving draft assemblies by iterative mapping and assembly of short reads to eliminate gaps. Genome Biol. 11 (2010).

Otto, T. D., Sanders, M., Berriman, M. & Newbold, C. Iterative correction of reference Nucleotides (iCORN) using second generation sequencing technology. Bioinformatics 26, 1704–1707 (2010).

Namiki, T., Hachiya, T., Tanaka, H. & Sakakibara, T. MetaVelvet: An extension of Velvet assembler to de novo metagenome assembly from short sequence reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e155 (2012).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: Prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 119 (2010).

Huson, D. H., Auch, A. F., Qi, J. & Schuster, S. C. MEGAN: Analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 17, 377–386 (2007).

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (2014).

Yin, Y. et al. DbCAN: A web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (2012).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Le, S. Q. & Gascuel, O. An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1307–1320 (2008).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Faust, K. & Raes, J. Microbial interactions: From networks to models. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 538–550 (2012).

Waite, D. W. & Taylor, M. W. Exploring the avian gut microbiota: Current trends and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 6, 673 (2015).

Butler, D. J. The habitat, food and feeding ecology of kakapo in Fiordland: A synopsis from the unpublished MSc thesis of Richard Gray. Notornis 53, 55–79 (2006).

Morrison, M., Pope, P. B., Denman, S. E. & McSweeney, C. S. Plant biomass degradation by gut microbiomes: More of the same or something new? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 358–363 (2009).

Hess, M. et al. Metagenomic Discovery of Biomass-Degrading Genes and Genomes from Cow Rumen. Science 331, 463–467 (2011).

Rahman, N. A. et al. A phylogenomic analysis of the bacterial phylum Fibrobacteres. Front. Microbiol. 6 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Department of Conservation (DOC) as well as a University of Auckland Faculty Research Development Fund grant (9841 3626187) to MWT, and a University of Auckland Doctoral Scholarship to DWW. We also gratefully acknowledge DOC staff for providing the kakapo samples used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W.W. and M.W.T. designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. D.W.W., Y.S. and P.H. analysed the metagenome, and D.W.W. and M.D. analysed the network data. All authors read and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waite, D.W., Dsouza, M., Sekiguchi, Y. et al. Network-guided genomic and metagenomic analysis of the faecal microbiota of the critically endangered kakapo. Sci Rep 8, 8128 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26484-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26484-4

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Bacterial communities along parrot digestive and respiratory tracts: the effects of sample type, species and time

International Microbiology (2023)

-

Gut microbiota of the threatened takahē: biogeographic patterns and conservation implications

Animal Microbiome (2022)

-

Influence of management practice on the microbiota of a critically endangered species: a longitudinal study of kākāpō chick faeces and associated nest litter

Animal Microbiome (2022)

-

Impact of coccidiostat and phytase supplementation on gut microbiota composition and phytate degradation in broiler chickens

Animal Microbiome (2019)