Abstract

Scientifically relevant misinformation, defined as false claims concerning a scientific measurement procedure or scientific evidence, regardless of the author’s intent, is illustrated by the fiction that the coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine contained microchips to track citizens. Updating science-relevant misinformation after a correction can be challenging, and little is known about what theoretical factors can influence the correction. Here this meta-analysis examined 205 effect sizes (that is, k, obtained from 74 reports; N = 60,861), which showed that attempts to debunk science-relevant misinformation were, on average, not successful (d = 0.19, P = 0.131, 95% confidence interval −0.06 to 0.43). However, corrections were more successful when the initial science-relevant belief concerned negative topics and domains other than health. Corrections fared better when they were detailed, when recipients were likely familiar with both sides of the issue ahead of the study and when the issue was not politically polarized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/vkygw/.

Code availability

All code for data analyses associated with the current submission is available at https://osf.io/vkygw/. Any updates will also be published in OSF.

References

Ahmed, W., Downing, J., Tuters, M. & Knight, P. Four experts investigate how the 5G coronavirus conspiracy theory began. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/four-experts-investigate-how-the-5g-coronavirus-conspiracy-theory-began-139137 (2020).

Heilweil, R. The conspiracy theory about 5G causing coronavirus, explained. Vox (2020); https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/4/24/21231085/coronavirus-5g-conspiracy-theory-covid-facebook-youtube

Pigliucci, M. & Boudry, M. The dangers of pseudoscience. The New York Times (2013); https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/10/the-dangers-of-pseudoscience/

Gordin, M. D. The problem with pseudoscience: pseudoscience is not the antithesis of professional science but thrives in science’s shadow. EMBO Rep. 18, 1482 (2017).

Townson, S. Why people fall for pseudoscience (and how academics can fight back). The Guardian (2016); https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2016/jan/26/why-people-fall-for-pseudoscience-and-how-academics-can-fight-back

Caulfield, T. Pseudoscience and COVID-19—we’ve had enough already. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01266-z (2020).

Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Lazy, not biased: susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition 188, 39–50 (2019).

Vraga, E. K. & Bode, L. Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Polit. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1716500 (2020).

Lewandowsky, S. et al. The Debunking Handbook 2020. Databrary https://doi.org/10.17910/b7.1182 (2020).

Pennycook, G. et al. Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature 592, 590–595 (2021).

Garrett, R. K., Weeks, B. E. & Neo, R. L. Driving a wedge between evidence and beliefs: how online ideological news exposure promotes political misperceptions. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 21, 331–348 (2016).

Lazer, D. M. J. et al. The science of fake news: addressing fake news requires a multidisciplinary effort. Science 359, 1094–1096 (2018).

Wyer, R. S. & Unverzagt, W. H. Effects of instructions to disregard information on its subsequent recall and use in making judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 533–549 (1985).

Greitemeyer, T. Article retracted, but the message lives on. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 21, 557–561 (2014).

McDiarmid, A. D. et al. Psychologists update their beliefs about effect sizes after replication studies. Nat. Hum. Behav.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01220-7 (2021).

Yousuf, H. et al. A media intervention applying debunking versus non-debunking content to combat vaccine misinformation in elderly in the Netherlands: a digital randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine 35, 100881 (2021).

Kuru, O. et al. The effects of scientific messages and narratives about vaccination. PLoS ONE 16, e0248328 (2021).

Anderson, C. A. Inoculation and counterexplanation: debiasing techniques in the perseverance of social theories. Soc. Cogn. 1, 126–139 (1982).

Jacobson, N. G. What Does Climate Change Look Like to You? The Role of Internal and External Representations in Facilitating Conceptual Change about the Weather and Climate Distinction (Univ. Southern California, 2022).

Pluviano, S., Watt, C. & Sala, S. D. Misinformation lingers in memory: failure of three pro-vaccination strategies. PLoS ONE 12, 15 (2017).

Maertens, R., Anseel, F. & van der Linden, S. Combatting climate change misinformation: evidence for longevity of inoculation and consensus messaging effects. J. Environ. Psychol. 70, 101455 (2020).

Chan, M. S., Jones, C. R., Jamieson, K. H. & Albarracin, D. Debunking: a meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1531–1546 (2017).

Janmohamed, K. et al. Interventions to mitigate vaping misinformation: a meta-analysis. J. Health Commun. 27, 84–92 (2022).

Walter, N. & Tukachinsky, R. A meta-analytic examination of the continued influence of misinformation in the face of correction: how powerful is it, why does it happen, and how to stop it? Commun. Res. 47, 155–177 (2020).

Walter, N., Cohen, J., Holbert, R. L. & Morag, Y. Fact-checking: a meta-analysis of what works and for whom. Polit. Commun. 37, 350–375 (2020).

Walter, N. & Murphy, S. T. How to unring the bell: a meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation. Commun. Monogr. 85, 423–441 (2018).

Walter, N., Brooks, J. J., Saucier, C. J. & Suresh, S. Evaluating the impact of attempts to correct health misinformation on social media: a meta-analysis. Health Commun. 36, 1776–1784 (2021).

Chan, M. S., Jamieson, K. H. & Albarracín, D. Prospective associations of regional social media messages with attitudes and actual vaccination: A big data and survey study of the influenza vaccine in the United States. Vaccine 38, 6236–6247 (2020).

Lawson, V. Z. & Strange, D. News as (hazardous) entertainment: exaggerated reporting leads to more memory distortion for news stories. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 4, 188–198 (2015).

Nature Microbiology. Exaggerated headline shock. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 377–377 (2019).

Pinker, S. The media exaggerates negative news. This distortion has consequences. The Guardian (2018); https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/17/steven-pinker-media-negative-news

CDC. HPV vaccine safety. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccinesafety.html (2021).

Jaber, N. Parent concerns about HPV vaccine safety increasing. National Cancer Institute https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2021/hpv-vaccine-parents-safety-concerns (2021).

Brody, J. E. Why more kids aren’t getting the HPV vaccine. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/13/well/live/hpv-vaccine-children.html (2021).

Walker, K. K., Owens, H. & Zimet, G. ‘We fear the unknown’: emergence, route and transfer of hesitancy and misinformation among HPV vaccine accepting mothers. Prev. Med. Rep. 20, 101240 (2020).

Normile, D. Japan reboots HPV vaccination drive after 9-year gap. Science 376, 14 (2022).

Larson, H. J. Japan’s HPV vaccine crisis: act now to avert cervical cancer cases and deaths. Lancet Public Health 5, e184–e185 (2020).

Soroka, S., Fournier, P. & Nir, L. Cross-national evidence of a negativity bias in psychophysiological reactions to news. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 18888–18892 (2019).

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C. & Vohs, K. D. Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5, 323–370 (2001).

Kunda, Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 108, 480–498 (1990).

Kopko, K. C., Bryner, S. M. K., Budziak, J., Devine, C. J. & Nawara, S. P. In the eye of the beholder? Motivated reasoning in disputed elections. Polit. Behav. 33, 271–290 (2011).

Leeper, T. J. & Mullinix, K. J. Motivated reasoning. Oxford Bibliographies https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199756223-0237 (2018).

Johnson, H. M. & Seifert, C. M. Sources of the continued influence effect: when misinformation in memory affects later inferences. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 20, 1420–1436 (1994).

Wilkes, A. L. & Leatherbarrow, M. Editing episodic memory following the identification of error. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A 40, 361–387 (1988).

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S. & Apai, J. Terrorists brought down the plane!—No, actually it was a technical fault: processing corrections of emotive information. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 64, 283–310 (2011).

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N. & Cook, J. Misinformation and its correction: continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 13, 106–131 (2012).

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine 33, 459–464 (2015).

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Richey, S. & Freed, G. L. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 133, e835–e842 (2014).

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. When corrections fail: the persistence of political misperceptions. Polit. Behav. 32, 303–330 (2010).

Rathje, S., Roozenbeek, J., Traberg, C. S., van Bavel, J. J. & van der Linden, S. Meta-analysis reveals that accuracy nudges have little to no effect for U.S. conservatives: regarding Pennycook et al. (2020). Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.25384/SAGE.12594110.v2 (2021).

Greene, C. M., Nash, R. A. & Murphy, G. Misremembering Brexit: partisan bias and individual predictors of false memories for fake news stories among Brexit voters. Memory 29, 587–604 (2021).

Gawronski, B. Partisan bias in the identification of fake news. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 723–724 (2021).

Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Lack of partisan bias in the identification of fake (versus real) news. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 725–726 (2021).

Borukhson, D., Lorenz-Spreen, P. & Ragni, M. When does an individual accept misinformation? An extended investigation through cognitive modeling. Comput. Brain Behav. 5, 244–260 (2022).

Roozenbeek, J. et al. Susceptibility to misinformation is consistent across question framings and response modes and better explained by myside bias and partisanship than analytical thinking susceptibility to misinformation. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 17, 547–573 (2022).

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N. & Cook, F. L. The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Polit. Behav. 36, 235–262 (2014).

Hameleers, M. & van der Meer, T. G. L. A. Misinformation and polarization in a high-choice media environment: how effective are political fact-checkers? Commun. Res. 47, 227–250 (2020).

Guay, B., Berinsky, A., Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. How to think about whether misinformation interventions work. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/OSF.IO/GV8QX (2022).

Hove, M. J. & Risen, J. L. It’s all in the timing: interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc. Cogn. 27, 949–960 (2009).

Tesch, F. E. Debriefing research participants: though this be method there is madness to it. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 35, 217–224 (1977).

Tanner-Smith, E. E. & Tipton, E. Robust variance estimation with dependent effect sizes: practical considerations including a software tutorial in Stata and SPSS. Res Synth. Methods 5, 13–30 (2014).

Tanner-Smith, E. E., Tipton, E. & Polanin, J. R. Handling complex meta-analytic data structures using robust variance estimates: a tutorial in R. J. Dev. Life Course Criminol. 2, 85–112 (2016).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw., https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03 (2010).

van Aert, R. C. M. CRAN—package puniform. R Project https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/puniform/index.html (2022).

Coburn, K. M. & Vevea, J. L. weightr: estimating weight-function models for publication bias. (2021); https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/weights/index.html

Fisher, Z. & Tipton, E. robumeta: an R-package for robust variance estimation in meta-analysis. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1503.02220 (2015).

Sidik, K. & Jonkman, J. N. Robust variance estimation for random effects meta-analysis. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 50, 3681–3701 (2006).

Hedges, L. V., Tipton, E. & Johnson, M. C. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 39–65 (2010).

JASP Team. JASP (2022); https://jasp-stats.org/

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br. Med. J. 327, 557–560 (2003).

Higgins, J. P. T. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558 (2002).

Tay, L. Q., Hurlstone, M. J., Kurz, T. & Ecker, U. K. H. A comparison of prebunking and debunking interventions for implied versus explicit misinformation. Br. J. Psychol. 113, 591–607 (2022).

Tappin, B. M., Berinsky, A. J. & Rand, D. G. Partisans’ receptivity to persuasive messaging is undiminished by countervailing party leader cues. Nat. Hum. Behav., https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01551-7 (2023).

Traberg, C. S. & van der Linden, S. Birds of a feather are persuaded together: perceived source credibility mediates the effect of political bias on misinformation susceptibility. Pers. Individ. Dif. 185, 111269 (2022).

van Bavel, J. J. & Pereira, A. The partisan brain: an identity-based model of political belief. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 213–224 (2018).

Kahan, D. M. Misconceptions, misinformation, and the logic of identity-protective cognition. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.2973067 (2017).

Levendusky, M. Our Common Bonds: Using What Americans Share to Help Bridge the Partisan Divide (Univ. Chicago Press, 2023).

Voelkel, J. G. et al. Interventions reducing affective polarization do not improve anti-democratic attitudes. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 55–64 (2023); https://doi.org/10.31219/OSF.IO/7EVMP

Ecker, U. K. H., Hogan, J. L. & Lewandowsky, S. Reminders and repetition of misinformation: helping or hindering its retraction? J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 6, 185–192 (2017).

Schwarz, N., Sanna, L. J., Skurnik, I. & Yoon, C. Metacognitive experiences and the intricacies of setting people straight: implications for debiasing and public information campaigns. in. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 39, 127–161 (2007).

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S. & Chadwick, M. Can corrections spread misinformation to new audiences? Testing for the elusive familiarity backfire effect. Cogn. Res Princ. Implic. 5, 41 (2020).

Kappel, K. & Holmen, S. J. Why science communication, and does it work? A taxonomy of science communication aims and a survey of the empirical evidence. Front. Commun. 4, 55 (2019).

Fischhoff, B. The sciences of science communication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14033–14039 (2013).

Winters, M. et al. Debunking highly prevalent health misinformation using audio dramas delivered by WhatsApp: evidence from a randomised controlled trial in Sierra Leone. BMJ Glob. Health 6, 6954 (2021).

Registered replication reports. Association for Psychological Science http://www.psychologicalscience.org/publications/replication (2017).

Vraga, E. K., Kim, S. C. & Cook, J. Testing logic-based and humor-based corrections for science, health, and political misinformation on social media. J. Broadcast Electron. Media 63, 393–414 (2019).

Vijaykumar, S. et al. How shades of truth and age affect responses to COVID-19 (mis)information: randomized survey experiment among WhatsApp users in UK and Brazil. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 1–12 (2021).

Anderson, C. A., Lepper, M. R. & Ross, L. Perseverance of social theories: the role of explanation in the persistence of discredited information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39, 1037–1049 (1980).

Sirlin, N., Epstein, Z., Arechar, A. A. & Rand, D. G. Digital literacy is associated with more discerning accuracy judgments but not sharing intentions. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinformation Rev., https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-83 (2021).

Arechar, A. A. et al. Understanding and reducing online misinformation across 16 countries on six continents. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://psyarxiv.com/a9frz/ (2022).

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Lu, J. G. & Rand, D. G. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 31, 770–780 (2020).

Jahanbakhsh, F. et al. Exploring lightweight interventions at posting time to reduce the sharing of misinformation on social media. in Proc. ACM on Human–Computer Interaction vol. 5, 1–-42 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2021); https://doi.org/10.1145/3449092 (2021).

Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2521–2526 (2019).

Gesser-Edelsburg, A., Diamant, A., Hijazi, R. & Mesch, G. S. Correcting misinformation by health organizations during measles outbreaks: a controlled experiment. PLoS ONE 13, e0209505 (2018).

Mosleh, M., Martel, C., Eckles, D. & Rand, D. Promoting engagement with social fact-checks online. Preprint at OSF https://osf.io/rckfy/ (2022).

Andrews, E. A. Combating COVID-19 Vaccine Conspiracy Theories: Debunking Misinformation about Vaccines, Bill Gates, 5G, and Microchips Using Enhanced Correctives. MSc thesis, State Univ. New York at Buffalo (2021).

Koller, M. Rebutting accusations: when does it work, when does it fail? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 23, 373–389 (1993).

Greitemeyer, T. & Sagioglou, C. Does exonerating an accused researcher restore the researcher’s credibility? PLoS ONE 10, e0126316 (2015).

Hedges, L. V. & Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-analysis (Academic, 1985).

Hedges, L. V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 6, 107 (1981).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J. & Rothstein, H. Introduction to Meta-analysis (Wiley, 2009).

Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 4, 863 (2013).

Morris, S. B. Distribution of the standardized mean change effect size for meta-analysis on repeated measures. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 53, 17–29 (2000).

Hart, W. et al. Feeling validated versus being correct: a meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol. Bull. 135, 555–588 (2009).

Lord, C. G., Ross, L. & Lepper, M. R. Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: the effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2098–2109 (1979).

Seifert, C. M. The continued influence of misinformation in memory: what makes a correction effective? Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 41, 265–292 (2002).

van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S. & Maibach, E. Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Glob. Chall. 1, 1600008 (2017).

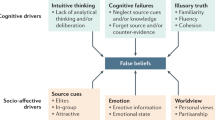

Ecker, U. K. H. et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 13–29 (2022).

Ecker, U., Sharkey, C. X. M. & Swire-Thompson, B. Correcting vaccine misinformation: A failure to replicate familiarity or fear-driven backfire effects. PLoS One, 18, e0281140 (2023).

Gawronski, B., Brannon, S. M. & Ng, N. L. Debunking misinformation about a causal link between vaccines and autism: two preregistered tests of dual-process versus single-process predictions (with conflicting results). Soc. Cogn. 40, 580–599 (2022).

Guenther, C. L. & Alicke, M. D. Self-enhancement and belief perseverance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 44, 706–712 (2008).

Misra, S. Is conventional debriefing adequate? An ethical issue in consumer research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 20, 269–273 (1992).

Green, M. C. & Donahue, J. K. Persistence of belief change in the face of deception: the effect of factual stories revealed to be false. Media Psychol. 14, 312–331 (2011).

Ecker, U. K. H. & Ang, L. C. Political attitudes and the processing of misinformation corrections. Polit. Psychol. 40, 241–260 (2019).

Sherman, D. K. & Kim, H. S. Affective perseverance: the resistance of affect to cognitive invalidation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 224–237 (2002).

Golding, J. M., Fowler, S. B., Long, D. L. & Latta, H. Instructions to disregard potentially useful information: the effects of pragmatics on evaluative judgments and recall. J. Mem. Lang. 29, 212–227 (1990).

Viechtbauer, W. & Cheung, M. W.-L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 112–125 (2010).

Borenstein, M. in Publication Bias in Meta-analysis: Prevention, Assessment, and Adjustments (eds Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J. & Borenstein, M.) 194–220 (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

Duval, S. in Publication Bias in Meta-analysis: Prevention, Assessment, and Adjustments (eds Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J. & Borenstein, M.) 127–144 (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

Peters, J. L., Sutton, A. J., Jones, D. R., Abrams, K. R. & Rushton, L. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 991–996 (2008).

Stanley, T. D. & Doucouliagos, H. Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias. Res. Synth. Methods 5, 60–78 (2014).

van Assen, M. A. L. M., van Aert, R. C. M. & Wicherts, J. M. Meta-analysis using effect size distributions of only statistically significant studies. Psychol. Methods 20, 293–309 (2015).

Pustejovsky, J. E. & Rodgers, M. A. Testing for funnel plot asymmetry of standardized mean differences. Res. Synth. Methods 10, 57–71 (2019).

Maier, M., Bartoš, F. & Wagenmakers, E. J. Robust Bayesian meta-analysis: addressing publication bias with model-averaging. Psychol. Methods, https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000405 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. O’Keefe, who assisted in the inter-rater reliability. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH114847 (D.A.), the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP1 DA048570 (D.A.) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AI147487 (D.A. and M.S.C.) and P30AI045008 (Penn Center for AIDS Research [Penn CFAR] subaward; M.S.C.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported by the Science of Science Communication Endowment from the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A. initiated the project, and M.S.C. supervised the project. Both M.S.C. and D.A. contributed to the theoretical formalism, developed the coding scheme and performed the coding reliability. M.S.C. took the lead in the data curation, preparing the analytical plan and performing the analytic calculations. Both M.S.C. and D.A. discussed the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Jon Roozenbeek, Sander van der Linden and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary analyses and results, Tables 1–5 and Fig. 1.

Supplementary Table

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, Mp.S., Albarracín, D. A meta-analysis of correction effects in science-relevant misinformation. Nat Hum Behav 7, 1514–1525 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01623-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01623-8

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Psychological inoculation strategies to fight climate disinformation across 12 countries

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)