Abstract

The electrical outputs of single-layer antiferromagnetic memory devices relying on the anisotropic magnetoresistance effect are typically rather small at room temperature. Here we report a new type of antiferromagnetic memory based on the spin phase change in a Mn-Ir binary intermetallic thin film at a composition within the phase boundary between its collinear and noncollinear phases. Via a small piezoelectric strain, the spin structure of this composition-boundary metal is reversibly interconverted, leading to a large nonvolatile room-temperature resistance modulation that is two orders of magnitude greater than the anisotropic magnetoresistance effect for a metal, mimicking the well-established phase change memory from a quantum spin degree of freedom. In addition, this antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory exhibits remarkable time and temperature stabilities, and is robust in a magnetic field high up to 60 T.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For more than 70 years since its discovery by M. Louis Néel1 in 1948, antiferromagnets have remained underutilized as key functional materials in spintronic devices. Instead, they have been primarily employed as pinning layers in devices such as spin valves because of their inherent net zero magnetic moments and ability to induce exchange bias with ferromagnetic materials. However, spintronic devices with antiferromagnets as key active elements have recently been developed and have attracted considerable attention owing to the absence of stray fields, ultrafast spin dynamics, and insensitivity to external magnetic fields2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, such as low-temperature spin-valve-like antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions10, room-temperature antiferromagnetic memory resistors switched by thermal heating assisted magnetic field11 or electrical-current-induced Néel spin-orbit torque12, and piezoelectric-strain-controlled antiferromagnetic memory devices13,14,15. In particular, piezoelectric strain excited by electric fields as an information writing method could be an ultralow-power mechanism due to the inhibition of Joule heating16,17,18.

However, a longstanding bottleneck issue in single-layer antiferromagnetic memory devices is that their electrical outputs based on the traditional relativistic anisotropic magnetoresistance are exceedingly small, approximately 0.1% at room temperature11,12,19. The amplification of the output signals of an antiferromagnetic memory has caused many challenges. To overcome this issue, inspired by the well-established phase change memory, where the resistance change of several orders of magnitude is achieved by the interconversion of amorphous and crystalline phases upon electrical excitations, we propose an idea of an antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory, for example, when the spin structure of an antiferromagnet changes from collinear to noncollinear, the resistance of this material could be remarkably altered.

We applied our hypothesis of this spin phase change memory to the Mn-Ir binary intermetallic system; this system exhibits a high-temperature (TN ~ 1145 K) collinear antiferromagnetic L10 MnIr phase when the Ir ratio is between 40% and 55%20,21,22,23,24,25 and a high-temperature (TN ~ 960 K) coplanar but noncollinear antiferromagnetic L12 Mn3Ir phase when the Ir ratio is between 15% and 35%20,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, as schematized in Fig. 1a. For bulk materials, intermetallic Mn-Ir with an Ir ratio between 35% and 40% is not stable20. However, for thin-film materials deposited by non-equilibrium techniques, such as sputtering and pulsed laser deposition onto oxide substrates, metastable Mn-Ir intermetallic films with Ir ratios between 35% and 40% could be successfully achieved. Once this composition boundary is obtained, the antiferromagnetic spin structure in such metastable films could be easily interconverted between the collinear and noncollinear configurations upon exposure to external stimuli, considering possible small free energy difference among the different spin structures close to the metastable composition boundary.

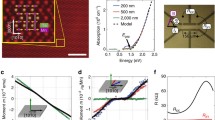

a Illustration of the different intermetallic phases for the antiferromagnetic (AFM) Mn-Ir binary system versus the Ir atomic concentration. b Rutherford backscattering and fitting curves of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure c Sketch of the electric-filed (EG)-gating measurement geometry for the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure. d EG-dependent resistance curves of the Mn-Ir thin film on the PMN-PT substrate at room temperature. e EG-dependent gate current (IG) of the PMN–PT substrate at room temperature. f Room-temperature out-of-plane magnetization curves of the Mn-Ir thin film after electric field pulse excitations of EG = − 4 and +1.5 kV·cm−1, respectively.

In order to realize the above hypothesis, we fabricated Mn-Ir thin films with a phase boundary composition of Mn62.5Ir37.5 utilizing magnetron sputtering onto ferroelectric 0.7PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3-0.3PbTiO3 (PMN-PT) substrates that could provide a piezoelectric strain stimulus. Accordingly, upon application of an external electric field perpendicularly to the ferroelectric PMN-PT substrate, a large nonvolatile resistance modulation of ~33% in the Mn-Ir thin film is obtained at 300 K. Systematic electrical, magnetic, and magnetotransport studies indicate that the resistance change is closely related to the spin phase change between the collinear and noncollinear structures in the Mn-Ir films. As a result, a room-temperature antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory is achieved. In addition, the resistance states of this novel memory device are highly stable over a wide temperature range, under a strong magnetic field, and for a long period. Overall, our experimental studies support our initial hypothesis of the antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory and provide a unique approach for enhancing the electrical signal outputs of antiferromagnetic spintronic devices.

Results

Structure and composition

The polycrystalline feature of the as-grown Mn-Ir thin film and the sharp interface between the film and the substrate can be observed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The composition of the Mn-Ir thin film was examined by Rutherford backscattering (RBS) technology, which is not particularly accessible, but it is accurate and widely used to determine the composition of thin films33,34,35,36. The experimental and fitted spectra shown in Fig. 1b revealed that the atomic concentration of Ir was approximately 37.5%. Moreover, since the PMN-PT substrate has multiple elements that could affect the RBS fitting, a Mn-Ir thin film was deposited on the Si substrate under the same conditions. This simpler RBS spectrum fitting further confirmed that the atomic concentration ratio of the Mn-Ir thin film was Mn62.5Ir37.5 (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results verified that composition-boundary Mn-Ir thin films were successfully fabricated20.

Electrical modulation

We then applied a perpendicular gate electric field EG to a Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure and examined the effect of EG on the resistance of the Mn-Ir thin film at room temperature. The measurement geometry is illustrated in Fig. 1c. It was found that the resistance of the Mn-Ir thin film is highly sensitive to EG. The linear four-probe resistance as a function of EG shown in Fig. 1d exhibits a hysteretic loop and a maximum resistance variation of ~41.5%. In this measurement, we used the unipolar switching approach13 (Fig. 1e) by applying a negative EG = −4 kV·cm−1 and a positive EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1 because ferroelectric oxides tend to crack during repeated bipolar electric field cycles37, and the unipolar switching could be effective in preventing cracking38. Two different states with an ~5.9 Ω resistance difference at EG = 0 kV·cm−1 are observed. The nonvolatile room-temperature resistance modulation is remarkably large and is ~33%.

In Fig. 1e, the gate current presents two peaks, which confirm polarization switching. On the other hand, the EG-dependent resistance curve is similar to the EG-dependent strain curve of PMN-PT39,40,41, which indicates that the resistance modulation induced by the electric field is predominantly due to piezoelectric strain instead of electrostatic carrier injection. Specifically, if an electrostatic modulation effect exists, a positive EG will induce an enhancement of the resistance of the Mn-Ir thin film since the major carriers in the Mn-Ir thin films are determined to be holes (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition, the high carrier density of the Mn-Ir thin film (Supplementary Fig. 3b) corresponds to a short Thomas-Fermi electrostatic screening length of several angstroms42; this length is much smaller than the thickness of our Mn-Ir thin film.

To investigate the effect of the piezoelectric strain on the magnetic properties of the Mn-Ir thin film, the magnetic moments of the Mn-Ir film were measured upon different electric field pulse excitations. For example, when an EG pulse of +1.5 kV·cm−1 is applied, the film shows negligible moment, which corresponds to a low-resistance state. In contrast, when an EG pulse of -4 kV·cm−1 is exerted, the Mn-Ir film exhibits a small hysteresis loop with a tiny net moment of ~10 mμB/Mn (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, we deposited a Co90Fe10 (CoFe) film and a Pt capping layer on top of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure. Then, the exchange bias of the Pt/CoFe/Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure after applying an EG pulse excitation of -4 and +1.5 kV·cm−1 was measured. As shown in Fig. 2, the coercivity field and the exchange bias field are ~7.1 mT and ~10 mT after the EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1 excitation, respectively, and then they change to 10.3 mT and 20 mT after applying an EG of −4 kV·cm−1 pulse. The switching of the coercivity field and the exchange bias field can be repeated for several cycles. Notably, the switching of the exchange bias is less likely to be induced by the change of the CoFe layer because the magnetic properties of a Pt/CoFe/PMN-PT heterostructure without a Mn-Ir layer are insensitive to the external electric field excitations (Supplementary Fig. 4). All these results indicate that the magnetic properties of the Mn-Ir thin film can be reversibly manipulated by the piezoelectric strain.

a Schematics of the Pt/CoFe/Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure, the exchange bias measurement geometry and the gate electric field switching geometry. b Room-temperature exchange bias of the heterostructure shown in (a) under the high-resistance state (HRS)/low-resistance state (LRS) excited by sequential positive/negative electric field pulses.

Subsequently, we measured the Hall resistance of the Mn-Ir thin film up to 18 T at room temperature for the two nonvolatile resistance states achieved by different electric field excitations. Intriguingly, a hysteretic loop of the Hall resistance was observed and indicates the existence of the anomalous Hall effect, for the high resistance state obtained by applying an EG pulse of −4 kV·cm−1. However, the Hall resistance curve versus magnetic field becomes a straight line for the low-resistance state upon applying an EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1 pulse (Fig. 3a). The anomalous Hall resistance of the high-resistance state exhibits a large coercivity field and an unsaturated loop, which is similar to the previous studies of the anomalous Hall effect in L12-type noncollinear antiferromagnetic Mn3Ir31,32 with nonvanishing Berry curvature43,44,45. For noncollinear antiferromagnets exhibiting the anomalous Hall effect, a small net moment is typically measurable due to the spin canting31,32,43,44,45. While for simple collinear antiferromagnets, the anomalous Hall effect is usually absent due to the lack of spin splitting, and accordingly, the net moment is close to zero for low magnetic fields. Therefore, the magnetic data in Fig. 1f and the Hall data in Fig. 3a consistently indicate that the spin structure of the Mn-Ir thin film is reversibly interconverted by different piezoelectric strain excitations between the L10-type collinear antiferromagnetic order and the L12-type noncollinear antiferromagnetic order, as schematized in Fig. 3b, c; this is closely accompanied by a large room-temperature resistance manipulation, as shown in Fig. 1d.

a Room-temperature Hall effect of the Mn-Ir thin film under the HRS/LRS attained by pulses of EG = −4 and +1.5 kV·cm−1, respectively. b Diagrammatic sketch of the collinear antiferromagnetic spin structure of the L10-type phase in the Mn-Ir thin film under the LRS triggered by an electric pulse of EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1. c Diagrammatic sketch of the noncollinear antiferromagnetic spin structure of the L12-type phase in the Mn-Ir thin film under the HRS triggered by an electric pulse of EG = −4 kV·cm−1.

Spin phase change

To further prove the above hypothesis, X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) spectroscopy were performed on the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure under different resistance states. Before each measurement, an in-plane magnetic field of 14 T was applied to the sample to align the possible magnetic moments. The results are shown in Fig. 4. When the Mn-Ir thin film is under the low-resistance state generated by an electric pulse of EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1, the XAS signals from left-polarized light and right-polarized light nearly overlap (Fig. 4a); thus, negligible signal is observed in the XMCD spectra (Fig. 4b), which indicates that no net magnetic moment could be detected within the detection limit. Notably, when the Mn-Ir thin film is under the high-resistance state achieved by an electric pulse of EG = −4 kV·cm−1, the XAS spectra exhibit evident differences between the two curves of left-polarized light and right-polarized light around the Mn L2,3 edges (Fig. 4c), and both positive and negative peak signals are observed in the XMCD spectra (Fig. 4d), which indicates net magnetic moments carried by the Mn atoms. These experimental results of XAS and XMCD suggest that the collinear/noncollinear antiferromagnetic orders correspond to the high-/low-resistance states, respectively, which coincide with our magnetic and Hall characterizations in the Mn-Ir thin film and provide more evidence for the spin phase change mechanism by electric fields.

a, b XAS (a) and XMCD (b) of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure under the LRS excited by an electric pulse of EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1. c, d XAS (c) and XMCD (d) of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure under the HRS realized by an electric pulse of EG = −4 kV·cm−1. The data were collected around manganese L2,3 edges at room temperature (300 K).

Additionally, the TEM images of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure under both the high- and low-resistance states indicate that the lattice of the Mn-Ir thin film under the high-resistance state is closer to the cubic L12 noncollinear antiferromagnetic phase of the Mn-Ir system. In contrast, the lattice of the Mn-Ir thin film under the low-resistance state is closer to the tetragonal L10 collinear antiferromagnetic phase (Fig. 5). Moreover, the variations in the lattice parameters of the Mn-Ir thin film under the high- and low-resistance states are in agreement with the compressive and tensile strains induced by the PMN-PT substrate after applying gate electric fields of EG = −4 kV·cm−1 and +1.5 kV·cm−1, respectively.

a, b Cross-sectional TEM image (a) and magnified image (b) of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure under the HRS generated via an electric pulse of EG = −4 kV·cm−1. c, d Cross-sectional TEM image (c) and magnified (d) of the Mn-Ir/PMN-PT heterostructure under the LRS excited by an electric pulse of EG = +1.5 kV·cm−1.

Furthermore, L12 noncollinear antiferromagnetic Mn3Ir (atomic ratio: Mn/Ir ~ 75/25) thin films and L10 collinear antiferromagnetic MnIr (atomic ratio: Mn/Ir ~ 50/50) thin films were fabricated as reference thin films. The noncollinear L12 Mn3Ir thin film exhibits an anomalous Hall effect and an uncompensated net magnetization, which is similar to that of the Mn-Ir thin film under the high-resistance state. Moreover, no anomalous Hall effect and no net magnetization are detected in the collinear L10 MnIr thin film, which is identical to that of the Mn-Ir thin film in the low-resistance state. The resistance values of the Mn3Ir and MnIr thin films detected at room temperature with similar electrical measurement geometries are close to the high- and low-resistance states of the Mn-Ir thin film, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results support that the Mn-Ir thin film clearly changes between its tetragonal and cubic phases due to the piezoelectric strain of the PMN-PT substrate generated via the gate electric field.

To obtain a reasonable physical picture of the spin phase change in the Mn-Ir thin film induced by piezoelectric strain, theoretical simulations on the free energies of the different spin configurations were performed. As elaborated in Supplementary Note 1, we theoretically identified a reasonable atomic configuration (Supplementary Fig. 6a) corresponding to the complex microstructure of the composition-boundary Mn-Ir thin film. For this crystal structure, the difference in the free energies of the collinear (Supplementary Fig. 6b) and noncollinear spin (Supplementary Fig. 6c) configurations is rather small, at only ~42 meV/unit cell. Thus, for a Mn-Ir film with an atomic composition between the stable collinear L10 and noncollinear L12 phases, subtle external energetic stimuli could easily lead to the interconversion between the collinear and noncollinear antiferromagnetic spin phases. These theoretical studies validate the physical principle of the new antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory.

On the other hand, the band structures and density of states (DOSs) for both collinear and noncollinear phases were also calculated (Supplementary Fig. 7). The results demonstrate that around the Fermi level, the electronic DOSs in the noncollinear phase are significantly lower than those in the collinear phase. This indicates that more conducting channels can be observed in the collinear phase. These findings are consistent with the experimental results, qualitatively illustrating the low-resistance characteristics of the collinear phase and the high-resistance characteristics of the noncollinear phase.

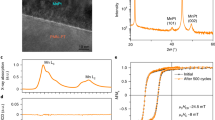

Memory Stability

To examine the stability of this spin phase change memory device, we measured the changes in the resistance states relative to temperature, magnetic field, and time. As shown in Fig. 6a, both the high- and low-resistance states subtly vary over a large temperature range of ~500 K. This excellent temperature stability of the resistive states originates from the transport feature that is likely impacted by multiple mechanisms in the Mn-Ir system, which exhibits a rather weak temperature dependence of the resistivity, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3c. More importantly, the difference between the high- and low-resistance states can be differentiated over the entire temperature range, which indicates that this memory device is capable of working over a large temperature range even above 200 °C. Figure 6b shows plots of the high- and low-resistance states versus the strong pulsed magnetic field. Remarkably, the two resistance states are rather robust over the perturbations of the pulsed magnetic field up to 60 T. This superior feature is a consequence of the combination of the rather high antiferromagnetic ordering temperature of Mn-Ir and the low carrier mobility (Supplementary Fig. 3d) that suppresses orbital scattering due to the Lorentz force. These results demonstrate that the Mn-Ir-based memory device can resist a high magnetic field up to 60 T. In addition, even throughout six months, no remarkable changes were observed for the high- and low-resistance states, which confirms the excellent time stability of the device (Fig. 6c). Overall, this antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory exhibits ultrahigh reliability upon temperature, magnetic field, and time variations.

Discussion

In summary, we have successfully fabricated composition-boundary Mn-Ir thin films onto functional ferroelectric PMN-PT substrates. At the composition boundary, the spin structure of the Mn-Ir films was highly sensitive to external stimuli. Upon piezoelectric excitations triggered by different electric fields, the antiferromagnetic spin structure is reversibly changed between a noncollinear and a collinear antiferromagnetic phase, leading to a large nonvolatile resistance variation of ~33%. Moreover, the resistance states were superiorly stable over a large temperature range of ~500 K, an ultrahigh magnetic field of 60 T or a long half-year time. Overall, our study has achieved a novel antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory with large electrical outputs and excellent reliabilities, mimicking the conventional phase change memory from the quantum spin degree of freedom.

In addition, the write cycle endurance in conventional phase change memories is typically limited by atomic migration characteristics46. However, according to the theoretical simulations, no atomic rearrangement occurs during the phase change in the Mn-Ir spin phase change memory, which indicates an unlimited write cycle endurance compared to that of conventional phase change memories. Moreover, the Mn-Ir system controlled by piezoelectric strain has potential applications in all-antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions as electrodes, which could introduce additional memory states and realize multiple-state storage47,48,49, thus providing a novel method for high-density storage and artificial synapses.

Methods

Growth

Mn-Ir thin films were grown onto (001)-oriented 0.7PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3−0.3PbTiO3 (PMN-PT) substrates using a d.c. sputtering technique with a Mn68Ir32 polycrystalline target. The base pressure of the sputtering system was 7.5 × 10−9 Torr. The deposition procedure was implemented at 500 °C with a sputtering power of 60 W and an Ar gas pressure of 3 mTorr. For the Pt/Co90Fe10/Mn-Ir/PMN-PT and Pt/Co90Fe10/PMN-PT heterostructures, both the Co90Fe10 films and the Pt films were deposited at room temperature in a d.c. the sputtering system using a Co90Fe10 polycrystalline target and a Pt target, respectively, with an Ar pressure of 3 mTorr. The growth rate of the Co90Fe10 thin film was 0.29 Å·s−1 with a sputtering power of 90 W, and the growth rate of the Pt thin film was 0.28 Å·s−1 with a sputtering power of 30 W.

Rutherford backscattering

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry of the Mn-Ir thin films on the PMN-PT substrate and the Si substrate was performed at the Centre for Ion Beam Applications at the National University of Singapore. The energy of He+ is 1.5 MeV, and the two detectors are positioned at 30 degrees and 90 degrees.

Transmission electron microscopy

The cross-section samples of the thin-film heterostructures were prepared by the focused ion beam technique. The transmission electron microscopy images were collected by an ARM 200CF (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 200 kV. HAADF images were acquired at an acceptance angle of 90–370 mrad.

Electrical measurements

A standard four-probe measurement geometry was used for the longitudinal resistance measurements, and the contacts were made by a wire bonding with Al wires. The electrical measurements were carried out in a Quantum Design VersaLab system utilizing the Delta measurement model supported by a Keithley 6221 current source and a Keithley 2182 A nanovoltmeter. Perpendicular gate electric fields were applied through another Keithley 2400 source meter. The standard Hall measurement geometry was used for the Hall measurements.

Magnetic measurements

Magnetic measurements were carried out in a Quantum Design superconducting quantum interference device.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

X-ray absorption and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy of the Mn-Ir thin film under different resistance states were collected at beamline 07U of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. The grazing incidence angle was 45°, and an in-plane magnetic field of 0.5 T was applied. The characteristic manganese L2,3 edge peaks were specifically measured.

High magnetic field transport measurements

Linear four-probe electrical contacts were made by silver paint and Au wires. The measurements were conducted at the Wuhan National High Magnetic Field Center. A 3 mA a.c. current with a frequency of 89 kHz was injected by a National Instruments PXI-5402 waveform generator for resistance measurements. The resulting voltage was measured by a National Instruments PXIe-5105 oscilloscope at a frequency of 4 MHz. To increase the accuracy of the high-frequency electrical resistance measurements, the middle two-probe voltage was amplified 100 times using a Stanford Research SR560 preamplifier.

Data availability

All the data that support the plots within this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

All the simulation codes in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Néel, M. L. Propriétées magnétiques des ferrites; Férrimagnétisme et antiferromagnétisme. Ann. Phys. -Paris 12, 137–198 (1948).

MacDonald, H. & Tosi, M. Antiferromagnetic metal spintronics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 369, 3098–3114 (2011).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Núñez, A. S., Duine, R. A., Haney, P. & MacDonald, A. H. Theory of spin torques and giant magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. B 73, 214426 (2006).

Gomonay, H. V. & Loktev, V. M. Spin transfer and current-induced switching in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 81, 144427 (2010).

Shick, A. B., Khmelevskyi, S., Mryasov, O. N., Wunderlich, J. & Jungwirth, T. Spin-orbit coupling induced anisotropy effects in bimetallic antiferromagnets: A route towards antiferromagnetic spintronics. Phys. Rev. B 81, 212409 (2010).

Plekhanov, E., Stroppa, A. & Picozzi, S. Magneto-electric coupling in antiferromagnet/ferroelectric Mn2Au/BaTiO3 interface. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 074104 (2016).

Manchon, A. et al. Current-induced spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035004 (2019).

Park, B. G. et al. A spin-valve-like magnetoresistance of an antiferromagnet-based tunnel junction. Nat. Mater. 10, 347–351 (2011).

Marti, X. et al. Room-temperature antiferromagnetic memory resistor. Nat. Mater. 13, 367–374 (2014).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587–590 (2016).

Yan, H. et al. A piezoelectric, strain-controlled antiferromagnetic memory insensitive to magnetic fields. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 131–136 (2019).

Qin, P. et al. Anomalous Hall effect, robust negative magnetoresistance, and memory devices based on a noncollinear antiferromagnetic metal. ACS Nano 14, 6242–6248 (2020).

Guo, H. et al. Giant piezospintronic effect in a noncollinear antiferromagnetic metal. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002300 (2020).

Matsukure, F., Tokure, Y. & Ohno, H. Control of magnetism by electric fields. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 209–220 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Antiferromagnetic piezospintronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1900176 (2019).

Yan, H. et al. Electric-field-controlled antiferromagnetic spintronic devices. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905603 (2020).

Bodnar, S. Y. et al. Magnetoresistance effects in the metallic antiferromagnet Mn2Au. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 014004 (2020).

Okamoto, H. The Ir-Mn (Iridium-Manganese) system. J. Phase Equilib. 17, 60–62 (1996).

Umetsu, R. Y. et al. Very high antiferromagnetic stability of L10-type MnIr alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 272-276, 790–791 (2004).

Umetsu, R. Y., Miyakawa, M. & Fukamichi, K. Pseudogap in the density of states and the highest Néel temperature of the L10-type MnIr alloy system. Phys. Rev. B 69, 104411 (2004).

Freitas, P. P., Ferreira, R., Cardoso, S. & Cardoso, F. Magnetoresistive sensors. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 19, 165221 (2007).

Ventura, J., Araujo, J. P. & Sousa, J. B. Training effect in specular spin valves. Phys. Rev. B 77, 184404 (2008).

Timopheev, A. A. et al. NiFe/CoFe/Cu/CoFe/MnIr spin valves studied by ferromagnetic resonance. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 17D713 (2013).

Yamaoka, T. Antiferroamgnetic in γ-phase Mn-Ir alloys. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 36, 445–450 (1974).

Tomeno, I., Fuke, H. N., Iwasaki, H., Sahashi, M. & Tsunoda, Y. Magnetic neutron scattering study of ordered Mn3Ir. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 3853 (1999).

Kohn, A. et al. The antiferromagnetic structures of IrMn3 and their influence on exchange-bias. Sci. Rep. 3, 2412 (2013).

Chen, H., Niu, Q. & MacDonald, A. H. Anomalous Hall effect arising from noncollinear Antiferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 017205 (2014).

Taylor, J. M. et al. Epitaxial growth, structural characterization, and exchange bias of noncollinear antiferromagnetic Mn3Ir thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 074409 (2019).

Taylor, J. M. et al. Magnetic and electrical transport signatures of uncompensated moments in epitaxial thin films of the noncollinear antiferromagnet Mn3Ir. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 062403 (2019).

Iwaki, H. et al. Large anomalous Hall effect in L12-ordered antiferromagnetic Mn3Ir thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 022408 (2020).

van der Veen, J. F. Ion beam crystallography of surfaces and interfaces. Surf. Sci. Rep. 5, 199–288 (1985).

Niu, C., Lu, Y. Z. & Lieber, C. M. Experimental realization of the covalent solid carbon nitride. Science 261, 334–337 (1993).

Jeynes, C. et al. Elemental thin film depth profiles by ion beam analysis using simulated annealing - a new tool. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 36, R97 (2003).

Chen, Z. et al. Electron accumulation and emergent magnetism in LaMnO3/SrTiO3 heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 156801 (2017).

Liu, Z. Q. et al. Electrically reversible cracks in an intermetallic film controlled by an electric field. Nat. Commun. 9, 41 (2018).

Lee, Y. et al. Large resistivity modulation in mixed-phase metallic systems. Nat. Commun. 6, 5959 (2015).

Zhang, S. et al. Electric-field control of nonvolatile magnetization in Co40Fe40B20/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)0.7Ti0.3O3 structure at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 137203 (2012).

Wu, S. Z. et al. Strain-mediated electric-field control of exchange bias in a Co90Fe10/BiFeO3/SrRuO3/PMN-PT heterostructure. Sci. Rep. 5, 8905 (2015).

Hou, W. et al. Strain-based room-temperature non-volatile MoTe2 ferroelectric phase change transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 668–673 (2019).

Liu, Z. Q. et al. Full electroresistance modulation in a mixed-phase metallic alloy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097203 (2016).

Nakatsuji, S., Kiyohara, N. & Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 527, 212–215 (2015).

Kiyohara, N. et al. Giant anomalous Hall effect in the chiral antiferromagnet Mn3Ge. Phys. Rev. Appl. 5, 064009 (2016).

Liu, Z. Q. et al. Electrical switching of the topological anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet above room temperature. Nat. Electron. 1, 172–177 (2018).

Kim, S., Burr, G. W., Kim, W. & Nam, S.-W. Phase-change memory cycling endurance. MRS Bull. 44, 710–714 (2019).

Qin, P. et al. Room-temperature magnetoresistance in an all-antiferromagnetic tunnel junction. Nature 613, 485–489 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Octupole-driven magnetoresistance in an antiferromagnetic tunnel junction. Nature 613, 490–495 (2023).

Shao, D.-F. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions for spintronics. npj Spintronics 2, 13 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Z.L. acknowledges the financial support of the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1602700). Z.L. acknowledges the financial support of the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFB3506000). Z.L. & C.J. acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52121001). Z.L. acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52271235). Z.L. acknowledges financial support by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. JQ23005). P.T. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12234011 and No. 12374053). Q.Z. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 52322212 and No. 52072400). P.Q. acknowledges the financial support of the China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (Grant No. BX20230451).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y. and H.M. contributed equally to this work. H.Y. performed sample growth and electrical and magnetic measurements, with assistance from P.Q., X.Z., X.W., H.C., Z.M., L.L., G.Z., and Z.D. J.W. and Z.Zhu performed the High magnetic field transport measurements. H.L. and A.A.B performed the RBS measurements. B.F. and Z.Zeng performed the patterned device fabrication. Q.Z. performed the TEM measurements. H.M. and P.T. performed the theoretical calculations. H.Y. wrote the manuscript, along with P.Q., X.Z., X.W., H.C., Z.M., L.L., and Z.L. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Z.L.,C.J. and P.Q. conceived and led the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ding-Fu Shao, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, H., Mao, H., Qin, P. et al. An antiferromagnetic spin phase change memory. Nat Commun 15, 4978 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49451-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49451-2

- Springer Nature Limited