Abstract

Staphylococcus capitis, which causes bloodstream infections in neonatal intensive care units, is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections. Thus, a standardized high-resolution typing method to document the transmission and dissemination of multidrug-resistant S. capitis isolates is required. We aimed to establish a core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) scheme to surveil S. capitis. The cgMLST scheme was defined based on primary and validation genome sets and tested with outbreaks of linezolid-resistant isolates and a validation set. Phylogenetic analysis was performed to investigate the population structure and compare it with the result of cgMLST analysis. The S. capitis population consists of 1 dominant, NRCS-A, and 4 less common clones. In this work, a multidrug-resistant clone (L clone) with linezolid resistance is identified. With the features of type III SCCmec and multiple copies of mutations of G2576T and C2104T in the 23S rRNA, the L clone has been spreading silently across China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Staphylococcus capitis, a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS), is one of the most widely distributed opportunistic pathogens. This organism causes a wide variety of diseases, including endocarditis, catheter-related bacteremia, prosthetic joint infections (PJIs), and skin infection1,2. In particular, it is known to cause nosocomial late-onset sepsis (LOS) in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs)3,4, which leads to increased rates of morbidity and mortality5,6. In some areas, S. capitis is the most frequently detected pathogen in NICUs infants, outranking even S. epidermidis4.

To date, only a few studies have investigated the population structure of S. capitis, except for the NRCS-A clone7, which has emerged as a major pathogen among newborns in NICUs and has been isolated in more than 17 countries throughout the world8. The NRCS-A clone was first reported by Rasigade et al. in 20124, who collected 40 S. capitis isolates from several French NICUs. SmaI pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) typing indicated that most isolates are clonally related and belong to the same clone, NRCS-A. Further studies have indicated that multidrug resistance, especially non-susceptibility to vancomycin, is an important advantage for epidemical success7 In addition to neonates in NICUs, this clone also causes healthcare-associated infections in adults such as PJIs9.

Phylogenetic analysis based on whole-genome sequencing and PFGE are the most frequently used methods to investigate the molecular epidemiology of S. capitis. However, PFGE is labor-intensive, whereas phylogenetic analysis requires expert phylogenetic knowledge and specialist hardware. The lack of reliable and easily applicable typing methods has resulted in an underestimation of the significance of S. capitis in the clinical spread of multidrug-resistant isolates.

With the development of whole-genome sequencing technology, the use of core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) to subtype and monitor outbreaks of bacteria is becoming more common. The typing ability of cgMLST has proven to be reliable for the typing of several pathogenic bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus10, Staphylococcus epidermidis11, Streptococcus mutans12, and Klebsiella pneumoniae13. The typing technology uses genome-wide gene-by-gene alleles from hundreds or thousands of genes conserved in all or most members of the species, and this confers the technology with a considerably higher resolution than that of PFGE14,15. Standardization is another important benefit of cgMLST. The standardized method, which can be easily performed using commercial software, makes it possible to compare the results among international laboratories. More importantly, cgMLST is a high-resolution, accessible, and replicable typing method to detect outbreaks and analyze the relationship between bacterial isolates. Stenmark et al. successfully applied cgMLST analysis in a surveillance project of clinical S. capitis isolates detecting the dissemination of NRCS-A clone from a Swedish NICU16, but this scheme is not publicly available and 1063 loci limited the discriminatory power.

The need for a standardized typing method is urgent, considering the emergence of multidrug-resistant clones, especially clones resistant to linezolid17,18,19. Linezolid-resistant S. capitis (LRSC) poses a serious threat to clinical practice. Linezolid resistance is associated with two major mechanisms: (1) mutation of the 23S rRNA or ribosomal proteins L3 and L420; and (2) acquisition of resistance genes such as the chloramphenicol-florfenicol resistance (cfr) gene21. The expression of Cfr methyltransferase confers resistance to linezolid and other ribosome-targeting antibiotics, which is known as the PhLOPSA resistance phenotype (resistance to oxazolidinones, phenicols, lincosamides, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A)22.

Here, we aimed to establish a cgMLST scheme for S. capitis. We developed a process to document the transmission and dissemination of multidrug-resistant S. capitis isolates, which involved three major steps. First, we detected the initial core genes with the primary genome set. Second, we improved the core genome using a validation genome set. Third, we evaluated the cgMLST scheme using a test genome set. With the aid of the newly established cgMLST scheme, we identified a unique multidrug-resistant clone, the L clone, which is widely distributed in China.

Results

Establishment of the S. capitis cgMLST scheme

All available genome assemblies of S. capitis in public genome database were collected and served as primary genome set. The core genome analysis of the primary genome set identified 2077 genes as comprising the core genome. After applying seven exclusion criteria, 1826 genes were obtained as the basis for the primary cgMLST scheme. Subsequently, the validation set was typed with this scheme, and 334 genes having an error rate of greater than 5% were excluded. Most of the error reports were for alleles containing a frame shift. After discarding the erroneous genes from the primary cgMLST scheme, we obtained the final cgMLST scheme, consisting of 1492 genes with a total length of approximately 1.39 megabases. The genes in the final cgMLST scheme had an average length of 931.5 bp (standard deviation, 580.8 bp; range, 90–7170 bp), with mean ± standard deviation GC content equal to 33.6 ± 3.0%. Overall, 1491 genes were detected in the reference genome CR01 chromosome, excluding gene “group_1475”, covering 55.1% of the full genome. The core genes were evenly distributed across the genome (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Evaluation and comparison of the S. capitis population structure using the cgMLST scheme

To evaluate the novel cgMLST scheme, the validation set containing 250 S. capitis genomes was used to create a minimum spanning tree with the default settings in Ridom (Ridom GmbH, Würzburg, Germany) (Fig. 1a). The cgMLST typing results showed that at least 95% of the target genes were present in all genomes (100%), with a median (interquartile range) of 99.87% (99.73–99.93%) of the 1492 target genes detected per genome. The number of non-typeable genes averaged to 3.2 ± 4.0 genes per genome (range, 0–24), which occurred mostly due to the absence of genes or early stop codons in those genes. The average number of alleles reported for each cgMLST target gene was 8.1 ± 3.7 (range, 1–30) alleles.

a Minimum spanning tree of the validation set and LRSC isolates using the core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) scheme. Groups were painted with different colors in the background. Nodes were painted with the same color according to the phylogenetic tree. b, c Enlarged image of the L clone, the region surrounded by a dotted frame in the minimum spanning tree. b is labeled with the year of isolation in different colors, whereas c is labeled with the city of isolation. d Map of China, showing the source of isolates labeled with a red node. The distances between cities are marked alongside the lines. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A total of 217 distinct cgMLST allelic profiles were identified for the 250 genomes (missing data disregarded in the pairwise comparisons), and only 21 profiles contained multiple genomes. Most genomes of the validation set (179 isolates) were separated into 35 related isolated groups. The largest four groups consisted of 29, 20, 15, and 10 genomes, respectively, and all belonged to clone NRCS-A.

To compare the typing results of cgMLST with other sequence-based methods, an SNP-based phylogenetic analysis of the validation set was performed (Fig. 2). In total, 90,821 variable sites were identified in the alignment concatemer of the core genome. The number of distinct genotypes defined by SNPs was 242, which was nearly equivalent to the distinct profiles identified with cgMLST (n = 217), indicating that cgMLST and core genome SNP provided comparable resolution in the validation set.

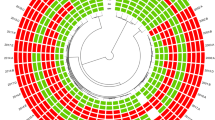

The bootstraps are represented by the darkness of the line, and almost all of them were >95%. The clusters are labeled with uppercase letters in each clade and painted with different colors. The tree is surrounded with color strips, indicating the SCCmec type, percentage of G2576T and C2104T, distribution of plasmids, and distribution of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, respectively. The shade of red in the 23s rRNA mutation represents the percentage of mutated copies, the lighter color indicates less mutation. The gene cfr and cfr-carrying plasmid are highlighted in red. The image with full information can be viewed in SVG format through this web link (https://itol.embl.de/export/122225230186443251631589900). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The SNP phylogenetic tree provided greater discrimination than the minimum spanning tree. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, the population can be generally divided into four clusters based on monophyletic groups. The largest cluster A, representing the NRCS-A clone, was divided into four sub-clusters: A1, A2, A3, and A4. Compared to the result of a previous phylogenetic analysis7, subgroups A1 and A2 corresponded to proto-outbreaks 1 and 2, whereas A3 and A4 were subdivisions of cluster outbreak. Other isolates, known as basal clones, could be divided into three major groups, namely, clusters B, C, and D. Although clusters B, C, and D were clearly separated by the cgMLST analysis, the subgroups of the NRCS-A clone were mixed together in the minimum spanning tree.

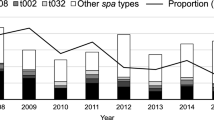

Application of cgMLST in LRSC isolates

We applied the cgMLST scheme to 31 LRSC isolates obtained from two independent outbreaks and sporadic cases. All 31 genomes were typeable and the median (interquartile range) of typeable genes was 99.93% (99.90–99.97%) (range, 99.3–100%). The 31 genomes were typed into 29 distinct cgMLST allele profiles, of which 30 genomes were closely related and formed two related groups. Excluding isolate LZD7, the largest allelic difference among the isolates was 25. The close genetic relationship among these LRSC isolates was also supported by the SNP-based phylogenetic analysis. These results were consistent with the results of the original publication of the outbreak analysis and indicated that a single S. capitis clone had spread around China. This was unexpected considering the tremendous geographical expanse of up to 1810 km and the wide time span, 10 years from 2008 to 2018 (Fig. 1b–d). Overall, we identified the clone having the feature of linezolid resistance and named it the L clone.

Genetic and clinical characteristics of the L clone

Antimicrobial resistance gene were unevenly distributed among the clusters. In the validation set, 89.2% (223/250) of the isolates carried SCCmec, and clade A1 was type IV, A2 was type II, and most of A3 and A4 were type V. All isolates of L clone, carried SCCmec and considered as methicillin-resistant S. capitis (MRSC). Furthermore, the L clone gained more resistance genes than the other clusters, including genes cfr, erm(A), aph(2’)-Ih, ant(4’)-Ia, ant(9)-Ia, bleO, and dfrC, which confer resistance to anti-ribosomal drugs, aminoglycoside, bleomycin, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMZ). Notably, all L clone isolates carried the qacA gene, which mediates resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds (Fig. 2). Except cfr, no other linezolid-resistance relevant genes, such as optrA and poxtA, were detected.

The outbreak of LRSC in Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital revealed the clinical characteristics of the L clone. All nine strains were isolated from patients with bacteremia (Table 1). All patients had associations with the intensive care unit (ICU) and had received antibiotics before the bacteremia episode, except for patients infected by LZD3, LZD6, and LZD7 (Fig. 3). During this period in our hospital, the AUD (antibiotics use density) every month ranged from 0.30 to 1.11 DDDs (defined daily dose per 100 patient-days) (Fig. 3). Susceptibility tests showed high levels of linezolid resistance (256 mg L−1), except in LZD6 and LZD7 (32 mg L−1) (Table 1). Besides resistance to linezolid, all isolates were methicillin resistant, with the cefoxitin MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) of 128 mg L−1 as listed in Table 1.

Nine clinical isolates were recovered from Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital. The blue rectangle represents the hospitalization progress, the dark blue rectangle indicates an intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and the light blue indicates a non-ICU stay. The red arrow indicates the isolation event. The light red line indicates the AUD of linezolid used in our hospital every month. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The whole genome sequence indicated that the cfr-carrying plasmid had clonal specificity. The hybrid assembly of LZD8 showed that this isolate contained three plasmids: pLZD8_1, pLZD8_2, and pLZD8_3. The cfr gene was carried by plasmid pLZD8_2. The result of the BLAST search on the NCBI GenBank showed that this cfr-carrying plasmid was highly homologous to plasmids pSR01(S. aureus), pXWZ_1(S. capitis), pH29-46(S. aureus), pLRSA47(S. aureus), and pSX01(S. xylosus). A comparison of the plasmids is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The three plasmids were detected among the examined genomes, and the results indicated that, unlike pLZD8_1, the plasmids pLZD8_2 and pLZD8_3 had strict clonal specificity, as they were detected only in clone L (Fig. 2).

The cfr-carrying plasmids from LZD1 and LZD8 were successfully conjugated to S. aureus 719 (ST5, cfr negative) but failed to conjugate to S. aureus ATCC29213-rifR. The transconjugants were named LZD1-719 and LZD8-719, both were identified as S. aureus and cfr positive. The transconjugant showed resistance to linezolid, and the resistance of chloramphenicol, gentamicin and clindamycin were also raised in these isolates, which can be explained by the gain of cfr gene (Supplementary Fig. 4). Revealed by linezolid E-test, the MIC of isolate 719 increased from 0.25 to 6 mg L−1 (LZD1-719) and 8 mg L−1 (LZD8-719).

Besides the presence of cfr, mutations in the 23S rRNA gene also contributed to linezolid resistance. The mutation of two linezolid resistance-related sites of 23S rRNA domain V, G2576T and C2104T, were detected in almost all the isolates with varied mutation percentages. All these L clone isolates harbored both mutations and the percentages of mutated copies ranged 66.7–100% and 50–100%, respectively. On the contrary, isolates from the other clones had relatively less percentages of mutated copies, with 0 to 29.4% mutated copies for C2104T and only one strain had G2576T mutation.

Discussion

As an opportunistic pathogen, S. capitis causes severe bacteremia and device-related infections in adult ICUs and NICUs. Due to the lack of appropriate typing methods for S. capitis, little is known about its population structure. This impedes the advancement of research on this bacterium. Thus, the introduced typing method helps to determine the characteristics of multidrug-resistant S. capitis clones.

Generally, the core genome refers to genes shared among a certain collection of isolates of the same species. However, the cgMLST scheme contains a fixed set of genes conserved across the genome. Therefore, the simple detection of the core genome did not fit the cgMLST scheme requirements. Therefore, we used a validation set to modify the primary core genome. In addition, no standard workflow for establishing the cgMLST scheme has been generally accepted to date.

Previously, in the process of establishing a novel cgMLST scheme, owing to the algorithm of the core genome detecting software, the core genome was detected based on a reference genome11,16. Subsequently, the genes contained in the reference genome are filtered against those in numerous other genomes; if a gene is present in all other isolates, then it was included as a core gene. However, using this method, one may miss many genes that should have been included as core genes if they are absent in the reference genome. Conversely, the higher the number of core genes, the better the resolution of the scheme.

To detect as many core genes as possible, we applied the pangenome analysis software “Panaroo”, which is a graph-based pangenome clustering tool that accounts for many of the sources of error introduced during the annotation of prokaryotic genome assemblies. Due to the extra error correction and gene refinding steps, Panaroo detects more core genes than other software, such as PanX, Roary, and COGsoft23. Panaroo does not require a reference genome, avoiding the introduction of reference-bias in the downstream analysis.

Another important aspect of establishing a new cgMLST scheme is to include a validation step with an additional genome set. In the traditional method, only two sets are used. One is used to detect the core genome, and the other is used to test the scheme. This strategy overlooks the population structure and validation step. Here, we engaged three different sets: the primary set, validation set, and LRSC isolates. We chose assembly files from NCBI and EMBL-ENA as the primary set to take advantage of the wide span of time and geographical expanse. The structure of the primary set was more balanced than that of the validation set (Supplementary Fig. 5), considering that the NRCS-A clone comprised most of the validation set. Therefore, in our opinion, the primary set was suitable for detecting the primary core genome, and the validation set was suitable to modify the core genome. With the aid of sufficient genomes and Panaroo, the novel cgMLST scheme contained 1492 loci, which is considerably more than that of the cgMLST scheme created by Stenmark and colleagues16, even filtered with strict criteria. As a result, the novel cgMLST scheme provides more discriminatory power almost close to SNP-based phylogenetic analysis.

In the present study, using cgMLST analysis and phylogenetic analysis, we identified a unique clone, the L clone. Isolates recovered from various cities, across a span of many years, may not have a close genetic relationship; thus, the results indicate the spreading of the clone across hospitals in China. Similar to other pathogens, Staphylococcus aureus24, Enterococcus faecium25, and coxsackievirus26, LRSC may spread across cities, for example, Shanghai and Hangzhou.

The hybrid assembly of LZD8 showed that linezolid resistance was conferred by the cfr-carrying plasmid pLZD8_2. This plasmid was found to be clonal specific, only being carried by the L clone. The structure of this plasmid and the mobile element carrying cfr have been well described in another study27. This plasmid was first reported as pLRSA47 identified from six linezolid-resistant methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates that belonged to ST5-II-t311 in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University in 201528. However, early in 2013, an ST5 MRSA strain, named H29, isolated from the milk of hospitalized cattle in the United States29 contained the plasmid pH29-46, which was 99% identical to pLRSA47 and pLZD8_2. Another plasmid, pSX01 (KP890694), was detected in a Staphylococcus xylosus strain recovered from a pig in Henan, China in 2015. The other two plasmids, pSR0130 and pXWZ_131 (KP890694), were detected in MRSA and S. capitis strains, respectively, as reported by our group. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, the comparison of these plasmids suggested that pLZD8_2 was distributed around the world from livestock farms to hospitals and caused linezolid resistance to spread among staphylococci. This was confirmed by the filter mating experiment from S. capitis to S. aureus in this study. However, the failure of filter mating experiment using ATCC29213-rifR strain indicated that this cfr-carrying plasmid could be host-specific.

Besides the presence of cfr, 23S rRNA mutations also contribute to linezolid resistance. Among the L clones, a few isolates did not carry the plasmid pLZD8_2 or cfr gene, but showed linezolid resistance (Supplementary Table 1). Using breseq, we mapped the genome reads to the 23S rRNA reference sequence and calculated the mutation proportion of each base. The mutation detection result indicated that the L clone is characterized by multiple copies of C2576G and C2104T mutations, in accordance with the findings of a previous study17. Based on this evidence, we inferred that the L clone might have been previously exposed to anti-ribosomal drugs such as linezolid or florfenicol, which are often used in the ICU. However, we do not have sufficient evidence to trace its origin.

The L clone contained more drug-resistant genes than other clones; thus, focus on this clone is required. Multiple antibiotic resistance of bacteria has led to increased morbidity and mortality, as well as increased adverse outcomes32. Resistance to antibiotics causes the L clone to successfully spread and persist in different ICUs. In addition, the extra resistance genes and plasmids result in a higher fitness cost33 than that of the NRCS-A clone, which is probably the reason that the L clone is not predominant.

According to previous epidemiological investigations34, the linezolid resistance rates of staphylococci were low, indicating that sporadic linezolid resistant staphylococci infection might not be a real threat in clinical settings. However, our results showed that the spread of the L clone was probably underestimated. With the help of the S. capitis cgMLST scheme, we are able to determine the actual role of the L clone in spreading multiple drug resistance. International surveillance projects are needed to detect the intercontinental spread of LRSC.

In conclusion, we have established a reliable cgMLST scheme for S. capitis, with a high resolution close to that of an SNP-based phylogenetic analysis. Using this scheme, we detected a widespread multidrug-resistant clone, and labeled it the L clone. Further epidemiological investigation is needed, and it is worth investigating the L clone to stop the further spread of drug resistance.

Methods

Ethics issues

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital (No. 20210319-33). Informed consent was waived, as the study used only anonymized clinical data unlinked to patient identifiers, and data produced in this study was not used for the treatment or management of patients.

Establishment and modification of the S. capitis cgMLST scheme

The workflow of scheme development is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. First, we collected all available genome assemblies of S. capitis in the NCBI GenBank database and the European Nucleotide Archive of European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL-ENA) as of June 11, 2021 using SRA Toolkit (https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools). A total of 142 genome assemblies, submitted from February 3, 2009 to May 19, 2021, were collected. After performing average nucleotide identity analysis (ANI) with pyANI35 (version 0.2.10), assembly quality control with panaroo-qc23, 136 genome assemblies were obtained, and they are listed in Supplementary Data 1; these assemblies served as the primary genome set.

After annotated using Prokka36, core genome analysis was performed using this primary genome set to obtain the primary cgMLST scheme. Core genes were detected with Panaroo23 (version 1.2.8) and filtered based on the following criteria: (1) discarding all genes that did not contain a start codon at the beginning of the gene; (2) discarding all genes that contained more than one stop codon or those that did not have a stop codon at the end of the gene; (3) discarding the genes that were shorter than 50 bp; (4) discarding the potential paralogs by comparing each locus against all alleles using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)37 (version 2.9.0+), with an identity of 0.9; (5) discarding the shorter gene if two genes were affected by an overlap of >3 bp on the reference chromosome CR01 (accession number LN866849); (6) collecting plasmids of S. capitis with Ridom SeqSphere+ software version 7.2.338 (Ridom GmbH, Muenster, Germany) (search date: June 18, 2021) and discarding genes homologous to those genes contained within plasmids; and (7) filtering genes that were homologous with the transposon_db in the TransposonPSI database39 (version 1.0.0).

Next, we modified the remaining core genes using a validation genome set. The validation genome set was collected from an international study of S. capitis7, consisting of 250 isolates from 22 countries worldwide, collected between 1994 and 2015. The raw reads (Fastq files) of the collection were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), with BioProject accession number PRJNA493527. We reassembled the genomes using Shovill (version 2.0.3, T. Seeman, unpublished, https://github.com/tseemann/shovill), and typed with the primary cgMLST scheme to acquire allelic profiles. The genes with error rates greater than 5% were removed from the primary cgMLST target genes40, resulting in the final version of the cgMLST scheme.

Evaluation of the cgMLST scheme

To validate the ability of the cgMLST scheme to cluster related isolates, we imported the genomes of the validation set to create a minimum spanning tree with the Ridom default setting, disregarding the missing data in the pairwise comparisons. Isolates with less than 24 allelic differences were considered to be the related isolated groups41.

Phylogenetic analysis of the validation genome set was performed to assess the population structure. Based on the core genome aligned sequences, IQ-TREE42 (version 2.0.3) was used to construct a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree was visualized and labeled using the iTOL43 Web service.

Application of cgMLST to LRSC typing

To evaluate the applicability of the S. capitis cgMLST scheme for outbreak analysis, we reanalyzed the published genomic data of S. capitis isolates from an outbreak in Shanghai17 and another independent outbreak in Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital in Hangzhou as well as two sporadic cases, one in Harbin and one in Hangzhou. All genomes included are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Nine LRSC isolates recovered from Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital from May 2016 to April 2017 were included in this study. Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) of common drugs were performed using agar or broth dilution methods according the recommendations of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)44. The genomes of those isolates were sequenced using a HiSeq X Ten platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads. The isolate LZD8 was randomly selected and sequenced using nanopore sequencing. The complete genome of LZD8 was constructed using hybrid assembly of short and long read sequences using Unicycler45 (version 0.4.8). The quality of the fastq files was examined using FastQC46 (version 0.11.9) and MultiQC47 (version 1.10.1). Assembly and annotation were performed using Shovill and Prokka36 (version 1.14.6). The clinical information of these nine isolates was collected. To evaluate the antibiotic pressure, the consumption of linezolid in our hospital was assessed using AUD (defined daily dose per 100 patient-days).

Genomic typing and resistance analysis

SCCmec typing was performed on all S. capitis genomes using SCCmecFinder on the CGE website (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SCCmecFinder/). Resistance genes were detected using ABRicate (version 1.0.0, https://github.com/tseemann/abricate). The existence of plasmids was detected in assembly files using BLAST. The mutation of 23S rRNA domain V in the isolates having an acquirable fastq sequence file was detected using breseq48 (version 2.0.3). All detected features were labeled using a heatmap or with color stripes around the phylogenetic tree.

Filter mating experiments

Filter mating experiments were performed to investigate whether the cfr carrying plasmid is conjugative. Using a clinical isolate S. aureus 719 (ST5, cfr negative) and ATCC29213-rifR as recipients and S. capitis LZD1 and LZD8 as donors with selection on nutrient agar plates containing 4 mg L−1 linezolid and 12.5 mg L−1 tetracycline or plates containing 4 mg L−1 linezolid and 50 mg L−1 rifampin according to the reference with adjustment in antibiotic concentrations49,50. The transconjugants were identified using MALDI-TOF and PCR of cfr gene with primers (cfr-fw: TGAAGTATAAAGCAGGTTGGGAGTCA; cfr-rv: ACCATATAATTGACCACAAGCAGC)51. Thereafter, antibiotic susceptibility test (K-B test and E-test) was performed to assess the change in drug resistance.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The genomes that included in the primary genome set were collected from public databases and those accession numbers were listed in Supplementary Data 1. The validation set was retrieved with BioProject accession number PRJNA4935277. As for the linezolid-resistant strains isolated in Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, the assembly files can be downloaded using the BioProject number PRJNA748212, and the complete genome of LZD8 can be downloaded with the GenBank accession number SAMN23101375. The genome of isolate XWZ can be downloaded with the accession number SAMN23101376. All data obtained or analyzed in this study underlying the figures in this manuscript are available in Supplementary Data 1 or in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Computer code is available from GitHub under https://github.com/gooday92/cgMLST_s_capitis.

References

Cui, B., Smooker, P. M., Rouch, D. A., Daley, A. J. & Deighton, M. A. Differences between two clinical Staphylococcus capitis subspecies as revealed by biofilm, antibiotic resistance, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiling. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 9–14 (2013).

Tevell, S., Hellmark, B., Nilsdotter-Augustinsson, Å. & Söderquist, B. Staphylococcus capitis isolated from prosthetic joint infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 115–122 (2017).

Van Der Zwet, W. C. et al. Nosocomial spread of a Staphylococcus capitis strain with heteroresistance to vancomycin in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 2520–2525 (2002).

Rasigade, J.-P. et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus capitis with reduced vancomycin susceptibility causes late-onset sepsis in intensive care neonates. PLoS One 7, e31548 (2012).

Brodie, S. B. et al. Occurrence of nosocomial bloodstream infections in six neonatal intensive care units. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19, 56–65 (2000).

Stoll, B. J. et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: The experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 110, 285–291 (2002).

Wirth, T. et al. Niche specialization and spread of Staphylococcus capitis involved in neonatal sepsis. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 735–745 (2020).

Laurent, F. & Butin, M. Staphylococcus capitis and NRCS-A clone: The story of an unrecognized pathogen in neonatal intensive care units. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 25, 1081–1085 (2019).

Tevell, S. et al. Presence of the neonatal Staphylococcus capitis outbreak clone (NRCS-A) in prosthetic joint infections. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–8 (2020).

Leopold, S. R., Goering, R. V., Witten, A., Harmsen, D. & Mellmann, A. Bacterial whole-genome sequencing revisited: Portable, scalable, and standardized analysis for typing and detection of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 2365–2370 (2014).

Jamet, A. et al. High-resolution typing of Staphylococcus epidermidis based on core genome multilocus sequence typing to investigate the hospital spread of multidrug-resistant clones. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59, e02454–02420 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. A core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus mutans. Msphere 5, e00348–00320 (2020).

Zhou, H., Liu, W., Qin, T., Liu, C. & Ren, H. Defining and evaluating a core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 8, 371 (2017).

Moura, A. et al. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 1–10 (2016).

Ruppitsch, W. et al. Defining and evaluating a core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 2869–2876 (2015).

Stenmark, B., Hellmark, B. & Söderquist, B. Genomic analysis of Staphylococcus capitis isolated from blood cultures in neonates at a neonatal intensive care unit in Sweden. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38, 2069–2075 (2019).

Ding, L., Li, P., Yang, Y., Lin, D. & Xu, X. The epidemiology and molecular characteristics of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus capitis in Huashan Hospital, Shanghai. J. Med. Microbiol. 69, 1079–1088 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Whole genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus capitis subsp. urealyticus strain LNZR-1. Gut Pathog. 6, 1–8 (2014).

Butin, M. et al. Emergence and dissemination of a linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus capitis clone in Europe. J. Antimicrobial Chemother. 72, 1014–1020 (2017).

Gu, B., Kelesidis, T., Tsiodras, S., Hindler, J. & Humphries, R. M. The emerging problem of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus. J. Antimicrobial Chemother. 68, 4–11 (2013).

Meka, V. G. et al. Linezolid resistance in sequential Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with a T2500A mutation in the 23S rRNA gene and loss of a single copy of rRNA. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 311–317 (2004).

Long, K. S., Poehlsgaard, J., Kehrenberg, C., Schwarz, S. & Vester, B. The Cfr rRNA methyltransferase confers resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A antibiotics. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 50, 2500–2505 (2006).

Tonkin-Hill, G. et al. Producing polished prokaryotic pangenomes with the Panaroo pipeline. Genome Biol. 21, 1–21 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Molecular evidence for spread of two major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones with a unique geographic distribution in Chinese hospitals. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 53, 512–518 (2009).

Sun, L. et al. Characterization of vanM carrying clinical Enterococcus isolates and diversity of the suppressed vanM gene cluster. Infect., Genet. Evolution 68, 145–152 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Large outbreak of herpangina in children caused by enterovirus in summer of 2015 in Hangzhou, China. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–5 (2016).

Schwarz, S. et al. Lincosamides, streptogramins, phenicols, and pleuromutilins: Mode of action and mechanisms of resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a027037 (2016).

Cai, J. C., Hu, Y. Y., Zhou, H. W., Chen, G.-X. & Zhang, R. Dissemination of the same cfr-carrying plasmid among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococcal isolates in China. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 59, 3669–3671 (2015).

Matyi, S. et al. Isolation and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains from a Paso del Norte dairy. J. Dairy Sci. 96, 3535–3542 (2013).

Wu, D. et al. Characterization of an ST5-SCCmec II-t311 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain with a widespread cfr-positive plasmid. J. Infect. Chemother. 26, 699–705 (2020).

Yang, X.-J. et al. Emergence of cfr-harbouring coagulase-negative staphylococci among patients receiving linezolid therapy in two hospitals in China. J. Med. Microbiol. 62, 845–850 (2013).

Friedman, N. D., Temkin, E. & Carmeli, Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 416–422 (2016).

San Millan, A. & Maclean, R. C. Fitness costs of plasmids: A limit to plasmid transmission. Microbiol. Spectrum 5, 5.5. 02 (2017).

Shariati, A. et al. The global prevalence of Daptomycin, Tigecycline, Quinupristin/Dalfopristin, and Linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase–negative staphylococci strains: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrobial Resistance Infect. Control 9, 1–20 (2020).

Pritchard, L., Glover, R. H., Humphris, S., Elphinstone, J. G. & Toth, I. K. Genomics and taxonomy in diagnostics for food security: Soft-rotting enterobacterial plant pathogens. Anal. Methods 8, 12–24 (2016).

Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Johnson, M. et al. NCBI BLAST: A better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W5–W9 (2008).

Jünemann, S. et al. Updating benchtop sequencing performance comparison. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 294–296 (2013).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (1997).

Neumann, B. et al. A core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for Enterococcus faecalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57, e01686–01618 (2019).

Earls, M. R. et al. Intra-hospital, inter-hospital, and intercontinental spread of ST78 MRSA from two neonatal intensive care unit outbreaks established using whole-genome sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1485 (2018).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259 (2019).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M100: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing 30th edn, 1–320 (CLSI, 2020).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005595 (2017).

Andrews, S. FastQC https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2012).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Deatherage, D. E. & Barrick, J. E. Engineering and Analyzing Multicellular Systems (Springer, 2014).

Cafini, F. et al. Methodology for the study of horizontal gene transfer in Staphylococcus aureus. JoVE (J. Vis. Exp.) 121, e55087 (2017).

Ruiz‐Ripa, L. et al. Linezolid‐resistant MRSA‐CC398 carrying the cfr gene, and MRSA‐CC9 isolates from pigs with signs of infection in Spain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 131, 615–622 (2021).

Kehrenberg, C. & Schwarz, S. Distribution of florfenicol resistance genes fexA and cfr among chloramphenicol-resistant Staphylococcus isolates. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 50, 1156–1163 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Xiaoliang Ba and Dr. Sebastian Bruchmann from University of Cambridge for initial comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W., C.G., Y.C., and Y.Y. designed this study; Z.W., F.Z., L.D., H.Z., S.J., H.W., Fei.Z., Yi.C., M.C., and X.L. performed experiments and literature investigation; Z.W., L.S., Y.F., J.Z., and Fei.Z. performed bioinformatics analysis; Y.Y and Y.C. supervised and directed this project; Z.W., C.G., and L.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jean-Philippe Rasigade, David Coleman, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Gu, C., Sun, L. et al. Development of a novel core genome MLST scheme for tracing multidrug resistant Staphylococcus capitis. Nat Commun 13, 4254 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31908-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31908-x

- Springer Nature Limited