Abstract

The recently discovered layered kagome metals AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs) exhibit diverse correlated phenomena, which are intertwined with a topological electronic structure with multiple van Hove singularities (VHSs) in the vicinity of the Fermi level. As the VHSs with their large density of states enhance correlation effects, it is of crucial importance to determine their nature and properties. Here, we combine polarization-dependent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy with density functional theory to directly reveal the sublattice properties of 3d-orbital VHSs in CsV3Sb5. Four VHSs are identified around the M point and three of them are close to the Fermi level, with two having sublattice-pure and one sublattice-mixed nature. Remarkably, the VHS just below the Fermi level displays an extremely flat dispersion along MK, establishing the experimental discovery of higher-order VHS. The characteristic intensity modulation of Dirac cones around K further demonstrates the sublattice interference embedded in the kagome Fermiology. The crucial insights into the electronic structure, revealed by our work, provide a solid starting point for the understanding of the intriguing correlation phenomena in the kagome metals AV3Sb5.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition-metal based kagome materials, hosting corner-sharing triangles, offer an exciting platform to explore intriguing correlated1,2,3 and topological phenomena4,5,6, including quantum spin liquid7,8,9,10,11, unconventional superconductivity12,13,14,15, Dirac/Weyl semimetals16,17,18, and charge density wave (CDW) order1,2,3,4,5,13,14,15,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Their emergence originates from the inherent features of the kagome lattice: substantial geometric spin frustration, flat bands, Dirac cones, and van Hove singularities (VHSs) at different electron fillings. Recently, a new family of kagome metal AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs)26 with V kagome nets, was found to feature a ℤ2 topological band structure27,28 and superconductivity was realized with a maximum Tc of 2.5 K at ambient pressure27. Moreover, they exhibit CDW order below TCDW ≈ 78–103 K29,30,31. Aside from the translational symmetry breaking in this CDW phase, the breaking of additional symmetries, i.e., rotation and time-reversal, was observed upon cooling down towards Tc29,32,33. Despite evidences supporting a nodeless gap from magnetic penetration depth measurements34, double superconducting domes under pressure35,36,37, a large residual in the thermal conductivity38 and an edge supercurrent in Nb/K1−xV3Sb5 suggest electronically driven and unconventional superconductivity39. It is widely believed that these exotic correlated phenomena are intimately connected with the multiple VHSs in the vicinity of the Fermi level40,41,42.

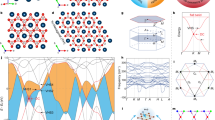

The characteristics of VHS bands are crucial in determining the Fermi surface instabilities13,14,15,19,20,21,22,23. From the perspective of band dispersion around the saddle point, VHSs can be classified into two types: conventional and higher-order43,44, as shown in Fig. 1e (i) and (ii). The higher-order VHS displays a flat dispersion along one direction with less pronounced Fermi surface nesting, generating a power-law divergent density of states (DOS) in two dimensions (2D) instead of a logarithmic divergent one43,44. Moreover, VHSs in kagome lattices possess distinct sublattice features: sublattice pure (p-type) and sublattice mixing (m-type), as shown in Fig. 1c. They induce an effective reduction of the local Coulomb interaction, thereby enhancing the role of non-local Coulomb terms13,14,40. Therefore, the nature of VHSs is pivotal to understand correlated phenomena, but still remains elusive in the kagome metals AV3Sb5 so far.

a The Lattice structure of kagome metals CsV3Sb5. b Real space structure of the kagome vanadium planes. The red, blue, and green coloring indicate the three kagome sublattices. c Two distinct types of sublattice decorated van Hove singularities (VHSs) in CsV3Sb5, labeled as p-type (sublattice pure, left panel) and m-type (sublattice mixing, right panel). d Density functional theory calculated electronic structure of CsV3Sb5. The red arrows mark the VHSs. e Schematics of the conventional VHS (i) and higher-order VHS (ii) in two-dimensional electron systems. The gray curves in (e) indicate the constant energy contours that show markedly flat features along the ky direction in higher-order VHS, as highlighted by the black arrow.

In this work, we perform a comprehensive study on the electronic structure of CsV3Sb5 by combining polarization-dependent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) measurements with density functional theory (DFT). The diverse nature of the four VHSs in the vicinity of the Fermi level (EF) is directly revealed. We observe three VHSs around the M point below the EF, formed by Vanadium 3d orbitals. Two of them are of conventional p-type, while the other one is of higher-order p-type. In addition, we find a conventional m-type VHS slightly above EF from our theoretical calculations. Furthermore, we show that the sublattice features are also embedded in the Dirac cone around the K point, exhibiting characteristic intensity modulations under various polarization conditions. Our study provides crucial insights into the electronic structure, thereby laying down the basis for a substantiated understanding of the correlation phenomena in the kagome metals AV3Sb5.

Results

Diverse nature of VHSs from theoretical calculations

CsV3Sb5 crystalizes in a layered hexagonal lattice consisting of alternately stacked V-Sb sheets and Cs layers. Each V-Sb sheet contains a 2D vanadium kagome net interweaved by a hexagonal lattice of Sb atoms (Fig. 1a). The vanadium kagome lattice, shown in Fig. 1b, hosts three distinct sublattices located at 3f Wyckoff positions. The toy band of the kagome lattice displays two different types of VHSs: p-type and m-type. For the p-type VHS, the states near the three M points are contributed by mutually different sublattices, while the eigenstates of the m-type VHS are equally distributed over mutually different sets of two sublattices for each M point, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. The band structure of CsV3Sb5 from DFT calculations is displayed in Fig. 1d, where four VHS points occur at M in the vicinity of EF (indicated by the red arrows and labeled as VHS1–4). Interestingly, VHS1 exhibits a much flatter dispersion along MK compared with the orthogonal direction MΓ. Further analysis shows that the quadratic contribution along MK is substantially reduced, indicating that VHS1 realizes a higher-order VHS (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for details). This is in contrast to the other three VHSs near EF which are all of conventional type with dominant quadratic dispersions in both directions. Motived by these observations, we perform ARPES measurements to investigate the electronic structure and focus on the nature of the VHSs in CsV3Sb5 which we infer from the polarization analysis.

Multiple VHSs identified by ARPES

The overall band dispersion and constant energy contours of CsV3Sb5 obtained via ARPES experiment are summarized in Fig. 2. The evolution of the electronic bands with different binding energy in Fig. 2a display sophisticated structures, including Sb contributed electron pockets near the zone center and kagome-derived Dirac cones at the K points with binding energy ~0.27 eV (Fig. 2a and b). Photon energy-dependent measurement reveals a weak kz dispersion of the Vanadium d-orbitals (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details), and we use the projected 2D BZ (\(\bar{\varGamma }\), \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\), \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)) hereafter. Moreover, our temperature dependent measurement shows that the CDW order has some effect on the band dispersion around \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point (see Supplementary Fig. 2). To reveal the VHS around \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point, we display the band structure along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{\varGamma }\) direction at 200 K in Fig. 2c, which are in good agreement with our DFT calculations (Fig. 2d). From the dispersion around \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point, we clearly identify three saddle points, denoted by VHS1, VHS2 and VHS3. Particularly, VHS1 and VHS2 are just slightly below EF with strong intensity (See Supplementary Fig. 3 for details). Photon energy-dependent measurement suggests weak kz dispersion of the VHS2 band but moderate kz dispersion of the VHS1 band (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Remarkably, VHS1 exhibits a pronounced flat dispersion that extends over more than half of the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) path. Indeed, by fitting the experimental spectra we find that the quadratic term is substantially smaller than the quartic one, revealing the higher-order nature of VHS1 (Fig. 2e, see Supplementary Fig. 4 for details). Notably, the measured dispersion around VHS1 is much flatter than the theoretical one, indicating that renormalizations due to the electronic correlations enhance the higher-order nature of VHS1 (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Stacking plots of constant energy contours at different binding energies (EB) showing sophisticated band structure evolution as a function of energy. b Fermi surface (i), constant energy contours (CEC) at EB of the Dirac point (DP) (ii), and CEC at the VHS3 (iii). c Experimental band dispersion along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{\varGamma }\) direction. The momentum direction is indicted by the red arrows in [b(i)]. The orange dashed lines indicate the energy position of the Fermi level, Dirac cone and VHS3. d Calculated bands along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{\varGamma }\) direction. e Fittings of the measured dispersion along the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) by \(E=M-{{b}_{2}k}_{y}^{4}\) form (the black line). The red dots represent the experimental data shown in (c) (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for the details). The red arrows in (c, d) mark the multiple VHSs. All measurements were probed with circularly polarized light, at 200 K, and the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) direction of the sample was aligned with the analyzer slit.

Orbital and sublattice characters of the VHSs

After directly identifying the VHSs in CsV3Sb5 from the band dispersion, we now turn to determining the sublattice nature of VHSs from the orbital symmetries by employing polarization-dependent ARPES measurements (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for experimental details). According to the selection rules in photoemission, bands can be selectively detected depending on their symmetry with respect to given mirror planes of the geometry45. Specifically, even- (resp. odd-) parity orbitals with respect to a mirror plane will be detected by the polarization whose electric field vector is in (resp. out of) the mirror plane. Our ARPES geometry is sketched in Fig. 3a. Polarization-dependent measurements were performed on the band structures along two orthogonal paths, \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) and \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{\varGamma }\) directions (Fig. 3b). We first employ circular polarization that can detect both even- and odd-parity orbitals to map out the full dispersions, as shown in Fig. 3c, d. To determine the orbital character of the bands, we further adopt linear horizontal (LH) polarization (Fig. 3e, f) and linear vertical (LV) (Fig. 3g, h) polarization. The electric field vector of LH and LV polarized light is in and out the mirror plane, respectively. Thus, when aligning the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) direction of the sample to along the analyzer slit, dxz, \(d_{{z}^{2}}\) and \(d_{{{x}^{2}}-{{y}^{2}}}\) are all of even symmetry with respect to the mirror plane and are detectable in the LH geometry. However, dyz and dxy are odd with respect to the mirror plane, and thus photoemission signals are only detectable in the LV geometry. Likewise, when the slit is along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) direction, the orbitals can be selected accordingly (see Supplementary Table I). Based on these selection rules (see supplementary Fig. 5 for details of the matrix element analysis), the orbital characters of the bands constituting the VHSs below EF can be clearly identified, as shown in Fig. 3i. The VHS1, VHS2, and VHS3 are attributed to \(d_{{{x}^{2}}-{{y}^{2}}}/d_{{z}^{2}}\), dyz an dxy orbitals, respectively. We note that the flat top of the VHS1 band exhibits relatively weak intensity along the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) direction in the LH polarization (Fig. 3e), while the full flat dispersion of the VHS1 can be observed at other photon energies (54, 108 eV, corresponding to kz = 0 as same as 78 eV), indicating that the diminished intensity of the flat-band top at 78 eV (Fig. 3e) is attributed to the matrix elements effect (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for details).

a Experimental geometry of our polarization-dependent ARPES. b The two-dimensional projection of the Brillouin zone and the high-symmetry directions. c, d Band dispersions along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) -\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) -\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) [Cut#1, (c)] and \(\bar{\varGamma }\) -\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) -\(\bar{\varGamma }\) [Cut#2, (d)] directions, respectively. The momentum directions of the cuts are indicated by the red arrows in (b). The bands were measured with circularly polarized light, at 200 K. e, f and g, h Same as (c, d), but probed with linear horizontal (LH) (e, f) and linear vertical (LV) (g, h) polarizations, respectively. We note that the intensity of the flat-top dispersion around the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point is weakened in (e), which may be due to the matrix element effects (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for the details of the matrix element analysis for the higher-order VHS band). i Experimental band structure along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{\varGamma }\) direction, with orbital characters marked. The momentum range is equal to the sum of the region I in (c) and region II in (d) selected by the red box. The dispersion is the same as the cut shown in Fig. 2c. j Orbital character resolved band structure from the A sublattice in the calculations, with irreducible band representations labeled. k The sign structure (blue/red) and spatial orientation of the \(d_{{{x}^{2}}-{{y}^{2}}}\)-orbital Ag p-type (inversion-even) and dxz-orbital B1u m-type type (inversion-odd) VHS. The phase orbitals are plotted in the positive kz plane. The black dots in the center of the hexagons indicate the inversion centers.

Discussion

With the experimental determination of the orbital character around the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point, we plot the theoretical orbital-resolved band dispersion in Fig. 3j originating from sublattice A (Fig. 1b), which is invariant under mirror reflection Mxz and Myz. Comparing the orbital characters around M point in Fig. 3i, j, we find a good agreement between the experimental and theoretical results. Furthermore, the states at VHS1, VHS2 and VHS3 at \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point, characterized by Ag, B2g and B1g irrep., are solely attributed to the A sublattice and inversion-even, confirming their p-type nature (Fig. 3k). The band top of dxz band at \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) is above EF and beyond experimental observation (Fig. 3i, j). However, our calculations show that this band belongs to B1u irrep. (inversion-odd, Fig. 3k) and is attributed to a mixed contribution from sublattices B and C, implying its m-type nature (see Supplementary Fig. 6). The four p-type and m-type VHSs, especially, the three of them (the VHS1, VHS2 and VHS4) are close to the Fermi level, suggesting that these VHSs with their large DOS and nontrivial sublattice and higher-order natures play a key role in driving the exotic correlated electronic states in AV3Sb5.

We further discuss the sublattice features of the Dirac cone bands around the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) point. The polarization dependent intensity patterns of the Dirac cones can convey the phase information of electronic wave functions, providing a way to determine the chirality of the Dirac cone6,46,47. Figure 4a displays representative constant energy contours of CsV3Sb5 around the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) point. The spectral intensity is strongly modulated around the kagome-derived Dirac cone for the LH polarization (Fig. 4b), with the maximum and minimum along the \(\bar{\varGamma }\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) direction but at opposite momentum direction above [Fig. 4a(i)] and below [Fig. 4a(iii)] the Dirac point [Fig. 4a(ii) and b]. Similar behavior is observed in LV polarization but in a reversed fashion (Fig. 4c, d). The intensity modulation around the Dirac cone, mimicking the case of graphene47 and the kagome metal FeSn6, indicates the chirality of the kagome-derived Dirac fermions in CsV3Sb5. The spectral intensity patterns (Fig. 4a, c) can be excellently reproduced in a spectral simulation based on sublattice interference of kagome initial states (Fig. 4e), further illustrating the sublattice interference embedded in the band structure of CsV3Sb5.

a Constant energy maps above (i), at (ii) and below (iii) the Dirac cone, respectively. The black arrows indicate the spectra intensity pattern of the Dirac cone. b Experimental band dispersion along the \(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\)-\(\bar{{{{{{\rm{K}}}}}}}\) direction. The data in (a) and (b) were probed with LH polarization. c, d Same as (a),(b), but measured with the LV polarization. All the experimental data (a–d) were obtained at 200 K. e Simulation of the constant energy map above (i) and below (ii) the Dirac cone for the LH polarization, based on the sublattice interference of kagome initial states. f Same as (e), but for the LV polarization. The red dashed lines in (a, c) and (e, f) show the Brillouin zone.

Our ARPES measurements, combined with DFT calculations, reveal the different natures of the four 3d-orbital VHSs near EF and the chiralities of the kagome-derived Dirac cones in CsV3Sb5. These are general features in the family of kagome metals AV3Sb5 and have important physical implications. For example, the nontrivial sublattice texture of the p-type VHSs leads, via sublattice interference, to a suppression of local Hubbard interactions and promotes the relevance of non-local Coulomb terms13,40. The bands from the conventional p-type VHS2 feature a good Fermi surface nesting, and the nesting vector connects parts of the Fermi surfaces dominated by different sublattices, which can lead to a 2 × 2 bond CDW instability. This could provide a reasonable explanation for the observed CDW order48,49. However, the origin of the CDW order is still under debate and phonons can play an important role30. The higher-order p-type VHS1, on the other hand, exhibits less pronounced Fermi surface nesting with large DOS, which could promote a nematic order43,44, providing a possible explanation for the additional crystal symmetry breaking in the CDW phase at lower temperature. The appearance of multiple types of VHSs near EF including both p-type and m-type, derived from the multi-orbital nature, can induce a rich competition for various pairing instabilities and thus generate numerous different orders depending on small changes in the electron filling40,41,42,43,44. The kagome metals AV3Sb5 offer the tantalizing opportunity to access and tune these orders via carrier doping or external pressure35,36,50,51,52,53,54, which remains to be further investigated both experimentally and theoretically.

Methods

Single crystals growth

Single crystals of CsV3Sb5 were synthesized using the self-flux method. All sample preparation is performed in an argon glovebox with oxygen and moisture <0.5 ppm. The flux precursor was formed through mechanochemical methods by mixing Cs metal (Alfa 99.98%), V powder (sigma 99.9%), and Sb beads (Alfa, 99.999%) to form a mixture which is ~50 at.% Cs0.4Sb0.6 (near eutectic composition) and 50 at.% VSb2. Note that prior to mixing, as-received vanadium powders were purified in-house to remove residual oxides. After milling for 60 m in a pre-seasoned tungsten carbide vial, flux precursors are extracted and sealed into 10 mL alumina crucibles. The crucibles are nested within stainless steel jackets and sealed under argon. Samples are heated to 1000 °C at 250 °C/h and soaked for 24 h before dropping to 900 °C at 100 °C/h. Crystals are formed during the final slow cool to 500 °C at 1 °C/h before terminating the growth. Once cooled, the crystals are recovered mechanically. Samples are hexagonal flakes with brilliant metallic luster. Elemental composition of crystals was assessed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) using an APREO-C scanning electron microscope.

ARPES measurements

The samples were cleaved in situ with a base pressure of better than 5 × 10−11 Torr. Angle-resolved photoemission (ARPES) measurements were performed at the ULTRA endstation of the Surface/Interface Spectroscopy (SIS) beamline of the Swiss Light Source. Data was acquired with a Scienta-Omicron DA30L analyzer using 78 eV photons with a total energy resolution of 18 meV. The Fermi level was determined by measuring a polycrystalline Au in electrical contact with the samples.

Computational methods

We employed first-principle calculations based on the density-functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the VASP1,2,3. The core electrons were treated using the projector-augmented wave method, and the exchange correlation energy was described by the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the PBE functional4. The cutoff energy for expanding the wave functions into a plane-wave basis was set to 500 eV. The Brillouin zone was sampled in k space within the Monkhorst–Pack scheme5 with a k mesh of 9 × 9 × 5, which achieved reasonable convergence of electronic structures. We have also done the calculations with spin–orbit coupling (SOC) and there are no qualitative changes except some gap openings, compared with the band without SOC. Therefore, we present the band structure without SOC in the main text to clearly identify the orbital characters. For all calculations, we used the experimentally determined crystal structure (space group P6/mmm, a = b = 5.4949 Å, c = 9.3085 Å).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Norman, M. R. Colloquium: Herbertsmithite and the search for the quantum spin liquid. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 041002 (2016).

Mielke, A. Ferromagnetic ground states for the Hubbard model on line graphs. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 24, L73–L77 (1991).

Pollmann, F., Fulde, P. & Shtengel, K. Kinetic ferro-magnetism on a Kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136404 (2008).

Ye, L. et al. Massive Dirac fermions in a ferromagnetic kagome metal. Nature (Lond.) 555, 638–642 (2018).

Yin, J.-X. et al. Quantum-limit Chern topological magnetism in TbMn6Sn6. Nature (Lond.) 583, 533–536 (2020).

Kang, M. et al. Dirac fermions and flat bands in the ideal kagome metal FeSn. Nat. Mater. 19, 163–169 (2020).

Wulferding, D. et al. Interplay of thermal and quantum spin fluctuations in the kagome lattice compound herbertsmithite. Phys. Rev. B 82, 144412 (2010).

Yan, S., Huse, D. A. & White, S. R. Spin-liquid ground state of the S = 1/2 Kagome Heisenberg antiferromagnet. Science 332, 1173–1176 (2011).

Han, T.-H. et al. Fractionalized excitations in the spin-liquid state of a kagome-lattice antiferromagnet. Nature (Lond.) 492, 406–410 (2012).

Han, T., Chu, S. & Lee, Y. S. Refining the spin Hamiltonian in the spin-1/2 Kagome lattice antiferromagnet ZnCu3(OH)6Cl2 using single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 157202 (2012).

Fu, M., Imai, T., Han, T.-H. & Lee, Y. S. Evidence for a gapped spin-liquid ground state in a kagome Heisenberg antiferromagnet. Science 350, 655–658 (2015).

Ko, W.-H., Lee, P. A. & Wen, X. -G. Doped kagome system as exotic superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 79, 214502 (2009).

Kiesel, M. L. & Thomale, R. Sublattice interference in the kagome Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 86, 121105(R) (2012).

Kiesel, M. L., Platt, C. & Thomale, R. Unconventional Fermi surface instabilities in the kagome Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 126405 (2013).

Wang, W.-S., Li, Z. -Z., Xiang, Y. -Y. & Wang, Q.-H. Competing electronic orders on kagome lattices at van Hove filling. Phys. Rev. B 87, 115135 (2013).

Liu, E. et al. Giant anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1125 (2018).

Morali, N. et al. Fermi-arc diversity on surface terminations of the magnetic Weyl semimetal Co3Sn2S2. Science 365, 1286–1291 (2019).

Liu, D.-F. et al. Magnetic Weyl semimetal phase in a Kagomé crystal. Science 365, 1282–1285 (2019).

Kohn, W. & Luttinger, J. M. New mechanism for superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 524–526 (1965).

Rice, T. M. & Scott, G. K. New mechanism for a charge-density-wave instability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 120–123 (1975).

Fleck, M., Oleś, A. M. & Hedin, L. Magnetic phases near the Van Hove singularity in s- and d-band Hubbard models. Phys. Rev. B 56, 3159–3166 (1997).

González, J. K. Luttinger superconductivity in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 78, 205431 (2008).

Gofron, K. et al. Observation of an “extended” Van Hove singularity in YBa2Cu4O8 by ultrahigh energy resolution angle-resolved photoemission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 3302 (1994).

Guo, H.-M. & Franz, M. Topological insulator on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 80, 113102 (2009).

Isakov, S. et al. Hard-core bosons on the kagome lattice: valence-bond solids and their quantum melting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 147202 (2006).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. New kagome prototype materials: discovery of KV3Sb5, RbV3Sb5, and CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 094407 (2019).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. CsV3Sb5: a ℤ2 topological Kagome metal with a superconducting ground state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 247002 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Topological surface states and flat bands in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Sci. Bull. 67, 495–500 (2022).

Jiang, Y.-X. et al. Discovery of unconventional chiral charge order in kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat. Mater. 20, 1353–1357 (2021).

Tan, H.-X., Liu, Y.-Z., Wang, Z.-Q. & Yan, B.-H. Charge density waves and electronic properties of superconducting kagome metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 046401 (2021).

Liang, Z. et al. Three-dimensional charge density wave and robust zero-bias conductance peak inside the superconducting vortex core of a kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031026 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Roton pair density wave and unconventional strong-coupling superconductivity in a topological kagome metal. Nature 559, 222–228 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Rotation symmetry breaking in the normal state of a kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat. Phys. 18, 265–270 (2022).

Duan, W. et al. Nodeless superconductivity in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 64, 107462 (2021).

Chen, K. Y. et al. Double superconducting dome and triple enhancement of Tc in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 247001 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Pressure-induced reemergence of superconductivity in topological Kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 103, 224513 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Highly-robust reentrant superconductivity in CsV3Sb5 under pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38, 057402 (2021).

Zhao, C. C. et al. Nodal superconductivity and superconducting domes in the topological Kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.08356 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Proximity-induced spin-triplet superconductivity and edge supercurrent in the topological Kagome metal, K1−xV3Sb5. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.05898 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Nature of unconventional pairing in the kagome superconductors AV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 177001 (2021).

Lin, Y.-P. & Nandkishore, R. M. Complex charge density waves at Van Hove singularity on hexagonal lattices: Haldane-model phase diagram and potential realization in kagome metals AV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 104, 045122 (2021).

Park, T., Ye, M. & Balents, L. Electronic instabilities of kagom ́e metals: saddle points and Landau theory. Phys. Rev. B 104, 035142 (2021).

Yuan, N. F. Q., Isobe, H. & Fu, L. Magic of high-order van Hove singularity. Nat. Commun. 10, 5769 (2019).

Classen, L., Chubukov, A. V., Honerkamp, C. & Scherer, M. M. Competing orders at higher-order Van Hove points. Phys. Rev. B 102, 125141 (2020).

Damascelli, A., Hussain, Z. & Shen, Z.-X. Angle-resolved photoemission studies of the cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 473–541 (2003).

Hwang, C. et al. Direct measurement of quantum phases in graphene via photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 84, 125422 (2011).

Liu, Y., Bian, G., Miller, T. & Chiang, T.-C. Visualizing electronic chirality and berry phases in graphene systems using photoemission with circularly polarized light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 166803 (2011).

Feng, X., Jiang, K., Wang, Z. & Hu, J. Chiral flux phase in the kagome superconductor AV3Sb5. Sci. Bull. 66, 1384–1388 (2021).

Denner, M. M., Thomale, R. & Neupert, T. Analysis of charge order in the kagome metal AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 217601 (2021).

Song, Y. et al. Enhancement of superconductivity in hole-doped CsV3Sb5 thin flakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 237001 (2021).

McChesney, J. L. et al. Extended van Hove singularity and superconducting instability in doped graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136803 (2010).

Luican, G. et al. Observation of van Hove singularities in twisted graphene layers. Nat. Phys. 6, 109–113 (2010).

Rosenzweig, P. et al. Overdoping graphene beyond the van Hove singularity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 176403 (2020).

Jones, A. J. H. et al. Observation of electrically tunable van Hove singularities in twisted bilayer graphene from NanoARPES. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001656 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank J.-F. He for helpful discussions. The work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under Grant. No. 200021-188413, and the NCCR MARVEL, a National Centre of Competence in Research, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 182892). The work at UC Santa Barbara was supported via the UC Santa Barbara NSF Quantum Foundry funded via the Q-AMASE-i program under award DMR-1906325. This research made use of the shared facilities of the NSF Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at UC Santa Barbara (DMR- 1720256). B.R.O. acknowledges support from the California NanoSystems Institute through the Elings Fellowship program. Y.H. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12004363). J.Z.M. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12104379), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021B1515130007). M.R. acknowledges the support of SNF Project No. 200021-182695. R.T. is funded by the DeutscheForschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) throughProject-ID 258499086 - SFB 1170 and through the Würzburg-DresdenCluster of Excellence on Complexity and Topology in Quantum Matter - ct.qmat Project-ID 390858490 - EXC 2147.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and M.S. designed the research. B.R.O. grew and characterized the crystals with guidance from S.D.W. X.W. and X.H. performed the theoretical calculations with the support from A.P.S. and R.T. Y.H. performed the ARPES experiments with help from S.J., N.C.P., J.Z.M., M.R. and M.S. Y.H. analyzed the data and discussed with N.C.P. Y.H. draw the figures with help from X.W. and M.S. Y.H. and X.W. wrote the paper with inputs from A.P.S. and M.S. All authors contributed to the discussions. M.S., A.P.S., and Y.H. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Wu, X., Ortiz, B.R. et al. Rich nature of Van Hove singularities in Kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Nat Commun 13, 2220 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29828-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29828-x

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

AV3Sb5 kagome superconductors

Nature Reviews Materials (2024)

-

The discovery of three-dimensional Van Hove singularity

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Low-energy electronic structure in the unconventional charge-ordered state of ScV6Sn6

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Conventional superconductivity in the doped kagome superconductor Cs(V0.86Ta0.14)3Sb5 from vortex lattice studies

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Imaging momentum-space Cooper pair formation and its competition with the charge density wave gap in a kagome superconductor

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2024)