Abstract

Nickel-based complex oxides have served as a playground for decades in the quest for a copper-oxide analog of the high-temperature superconductivity. They may provide clues towards understanding the mechanism and an alternative route for high-temperature superconductors. The recent discovery of superconductivity in the infinite-layer nickelate thin films has fulfilled this pursuit. However, material synthesis remains challenging, direct demonstration of perfect diamagnetism is still missing, and understanding of the role of the interface and bulk to the superconducting properties is still lacking. Here, we show high-quality Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films with different thicknesses and demonstrate the interface and strain effects on the electrical, magnetic and optical properties. Perfect diamagnetism is achieved, confirming the occurrence of superconductivity in the films. Unlike the thick films in which the normal-state Hall-coefficient changes signs as the temperature decreases, the Hall-coefficient of films thinner than 5.5 nm remains negative, suggesting a thickness-driven band structure modification. Moreover, X-ray absorption spectroscopy reveals the Ni-O hybridization nature in doped infinite-layer nickelates, and the hybridization is enhanced as the thickness decreases. Consistent with band structure calculations on the nickelate/SrTiO3 heterostructure, the interface and strain effect induce a dominating electron-like band in the ultrathin film, thus causing the sign-change of the Hall-coefficient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The search for the nickelate superconductivity was enthused by the idea of mimicking the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\,\)orbital of the single-band high-Tc cuprates1. However, the recent results indicate the complex multiband structures in doped infinite-layer nickelates, suggesting a new family of superconductivity1,2. Numerous theoretical works have been conducted based on the bulk pictures;2 however, the superconductivity has only been observed in epitaxial Nd1-xSrxNiO2 and Pr1-xSrxNiO2 ultrathin films (up to ~10 nm) with an infinite-layer structure1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. In contrast, infinite-layer nickelates prepared in bulk form show only insulating behavior10,11,12. Moreover, the DC diamagnetic response in the superconducting thin films has never been demonstrated1. These beg the question of whether the superconductivity occurs in the whole film or at the interface between the nickelate and SrTiO3 (STO) substrate13,14,15,16. Theoretical calculation further proposed that the interface/surface-induced Fermi surface modification causes the transformation from a d-wave paring in bulk into an s-wave paring at the interface/surface2,17, which might be consistent with the recent observation of two gaps from the tunneling spectrum measurement5. This further adds to the puzzle of whether the observed electronic properties are associated with the bulk or the heterostructure interface. In this work, we comprehensively investigate the Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 films of various thicknesses to confirm the bulk nature of the superconductivity and reveal the interfacial effects on the multiband picture of the infinite-layer nickelate thin films and demonstrate their perfect DC diamagnetic response.

Results

Infinite-layer structure

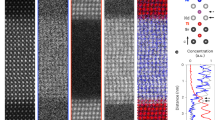

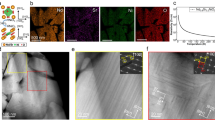

Figure 1a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) θ–2θ patterns of the Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films of different thicknesses from 4.6 to 15.2 nm. The XRD characterization of the as-grown perovskite Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO3 thin films can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1. The obvious diffraction peak and thickness oscillations (Laue fringes) in the vicinity of the (00l) infinite-layer peak (l is an integer) indicate the high crystallinity of the films. The (00l) peak positions slightly shift towards a higher angle as the thickness increases, indicating a shrinking of the c axis, with the lattice constants c change from ~3.42 Å for the 4.6-nm film to ~3.36 Å for the 15.2-nm film, as plotted in Fig. 1b. It has been shown that Nd1-xSrxNiO2 (x ≤ 0.2) bulks exhibit an in-plane lattice constant (3.914–3.921 Å) slightly larger than that (3.905 Å) of STO substrate10,11, suggesting the presence of compressive strain on the films imposed by the substrate. The extent of compressive strain decreases as the film thickness increases and thus causing the shrinking of c. Figure 1c shows the high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image of the 10.1-nm film. A clear infinite-layer structure is observed with no obvious defect throughout the layer.

a The XRD θ–2θ scan patterns of the Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films with different thicknesses on SrTiO3 substrates. The intensity is vertically displaced for clarity. b The room-temperature c-axis lattice constants, c, as a function of thickness, as calculated from the (001) peak positions. The red dots represent the average c of the two sets of samples and the error bars represent the variance. c The HAADF-STEM image of the 10.1-nm Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 on SrTiO3 substrate.

Electronic properties

The resistivity versus temperature (ρ-T) curves for the Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films are shown in Fig. 2a, and the zoomed-in ρ-T curves at temperatures from 50 to 2 K are shown in the inset. All the samples behave like a metal at the normal state and are superconducting at low temperatures. The onset superconducting transition temperature Tc,90%R (defined as the temperature at which the resistivity drops to 90% of the value at 15 K) and zero-resistance Tc,zero-R decrease with decreasing thickness (Fig. 2f). Figure 2b shows the corresponding temperature dependence of the normal-state Hall coefficients (RH) of the Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 films. The RH for samples with a thickness higher than 6.8 nm shows a negative sign at room temperature and undergoes a smooth transition to a positive sign at a low temperature of ~50 K, consistent with previous observation at the doping level x = 0.21,3,4. However, as the thickness decreases to 6.8 nm, the RH sign-change temperature decreases to 22 K. The RH even remains negative at the whole temperature range below 300 K for the films with thickness lower than 6.8 nm. Figure 2e presents the thickness dependence of the RH at 20 K and 300 K, clearly showing a sign-change from positive to negative with decreasing thickness. This suggests a change of the multiband structures upon reducing thickness.

a The resistivity versus temperature (ρ-T) curves of the Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films with different thicknesses from 4.6 to 15.2 nm. The inset shows the zoomed-in ρ-T curves at temperatures from 50 to 2 K. b The temperature dependence of the normal-state Hall coefficients RH. c The temperature dependence of magnetization (M-T curve) with zero-field cooling (ZFC) for Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films with different thicknesses from 5.5 to 15.2 nm. d The zoomed-in M-T curves at temperatures from 20 to 2.1 K with field cooling (FC) and ZFC for the sample with a thickness of 7.5 nm. The measurement and cooling fields are 20 Oe. The magnetic field is applied perpendicularly to the a-b plane. e The RH at T = 300 and 20 K as a function of thickness. f The critical temperature, Tc, as a function of thickness. The Tc,90%R is defined as the temperature at which the resistivity drops to 90% of the value at 15 K (the onset of the superconductivity). The Tc,zero-R, is defined as the temperature at which the resistivity drops to be zero and Tc,dia is defined as the temperature at the onset of the diamagnetic response. The solid and open square for Tc,90%R and Tc,zero-R are the average value of two sets of samples shown in the main text and Supplementary Information, and the error bars represent the variation. The dash lines in (b) and (e) show the position where the RH is zero.

Diamagnetic response

Figure 2c shows the temperature dependence of magnetization (M-T curves) under zero-field cooling (ZFC) mode for Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films with thickness varying from 5.5 to 15.2 nm. The normal-state magnetization shows temperature independence. Upon cooling down, the magnetization drops steeply to negative values, confirming the occurrence of superconducting transition in the thin films. Figure 2d shows the zoomed-in M-T curves from 20 down to 2.1 K with ZFC and field cooling (FC) for a representative sample with a thickness of 7.5 nm. Similar to the behavior of typical bulk superconductors, a clear diamagnetic transition is seen, and the onset transitions are the same under ZFC and FC modes, unambiguously confirming the existence of the superconducting phase. The ZFC and FC M-T curves for other thin films are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the magnetization measured with the applied magnetic field parallel to the ab plane H || ab (in-plane). Compared to H || c, the change of in-plane magnetization is negligible upon cooling. This is because the film is ultrathin (the maximum thickness of the infinite layer is around 11 nm) and is thinner than the out-of-plane London penetration depth. As the magnetic field is applied parallel to the ab plane, the magnetic field fully penetrates the film, and therefore, the absence of Meissner effect is observed. In certain cases, a small diamagnetic response is observed when H || ab with transition temperature similar to that of measured in H || c, which is likely due to imperfect in-plane alignment of the sample during measurement. The Tc,dia, defined as the onset transition temperature in diamagnetic response, is shown in Fig. 2f. It is found that Tc,dia is slightly lower than Tc,zero-R, possibly due to filament superconducting domains or presence of inhomogeneity of the superconducting phase in the thin films. Only well below the zero-resistance temperature, the phase coherence occurs in the entire films, and therefore, the Meissner effect is observed. Supplementary Fig. 4a shows the volume susceptibility as a function of temperature, which accounts for the demagnetizing field Hd = −NM. A large χv(T = 2K) < −0.9 can be observed (for 7.5 nm ZFC MT) which indicates a superconducting volume fraction of >90%, suggesting very few non-superconducting unreduced phases or impurities in the sample. In addition, Meissner effect is observed as the negative slope in M-H curve below superconducting temperature, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4b.

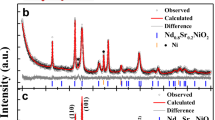

Electronic structure

The unoccupied states of energy bands are crucial to determine the transport properties and could be detected by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) on oxygen and transition metal edges. To carefully characterize the electronic structures of samples with pure perovskite phase and the resultant infinite-layer phase, we restrict our XAS measurements on thin films with thickness no >10.1 nm, as confirmed by XRD measurements. Figure 3a shows the O K edge XAS of 10.1-nm perovskite Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO3 and infinite-layer Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films. A prominent pre-peak at ~528.9 eV is observed near the O K-edge XAS in Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO3 film, which is attributed to the presence of a ligand hole in oxygen18,19,20. In perovskite nickelates, the oxygen p to nickel d band charge-transfer energy is negative, the electrons spontaneously transfer from oxygen ligands to Ni cations, leaving the holes on the oxygen side even without chemical doping18. Excitation of oxygen 1 s core electrons to such unoccupied states (holes) give rise to the pre-peak in O K-edge XAS. The ligand holes in perovskite Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO3 can also be suggested from the Ni L2,3 edge XAS (Fig. 3b), in which a shoulder is visible at ~856 eV corresponding to the electron transition from the Ni core-level 2p to 3d8L state (L is ligand hole), beside the main sharp peak at ~854.5 eV corresponding to the electron transition from the core-level 2p to 3d7 state18. As the film is reduced from perovskite to infinite-layer structure, the prominent pre-peak in Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 film disappears, which is consistent with the previous study in underdoped RNiO2 (R = La, Nd)19,20. Instead, another pre-peak with less intensity at a higher energy of ~530.5 eV is observed, suggesting that the oxygen ligand hole is still present in the infinite-layer film. In the Ni L2,3 edge XAS (Fig. 3b), the main absorption peaks in both films are observed with a position shift to a lower energy for infinite-layer film, consistent with the reduced Ni valence state as the structures evolve from perovskite to infinite layer21. The shoulder is still observed in the infinite-layer Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 beside the main peak, even though it shifts to a higher energy position and its intensity is lower compared with that of the perovskite film. This further suggests the presence of oxygen ligand hole state in infinite-layer nickelates.

The parent compound of the canonical cuprate superconductor is a charge-transfer insulator according to the Zaanen-Sawatzky-Allen scheme22. The doped holes reside at the oxygen sites due to the strong hybridization of Cu-\(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and O-2p orbitals forming the 3d9L states, and therefore, the pre-peak of O K edge emerges upon doping23. The spin of the doped holes in oxygen sites and spin in Cu site form the Zhang-Rice singlet state, reducing the cuprate to be an effective single-band system24. Whether a similar situation occurs in infinite-layer nickelate, however, is far from clear. The theoretical model suggests that the parent compound NdNiO2 is a Mott-Hubbard insulator, in which the O 2p band is below Ni 3d lower Hubbard Band25,26. This has been suggested by the EELS and XAS measurements that the pre-peak near the O K edge is completely suppressed in undoped NdNiO2 and LaNiO219,20. The pre-peak nature in doped Nd1-xSrxNiO2 has not been fully explored by XAS since the STO capping layer obscures the absorption from the underlying nickelate films27. Our observation of the obvious pre-peak in O K edge and shoulder in Ni L2,3 edge in Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 films, which is similar to the cuprate28, suggests the Ni-O orbital hybridization in infinite-layer nickelate. Note that the EELS measurements have also shown the pre-peak feature in Nd1-xSrxNiO2 with increasing doping, although the intensity is weak20. Moreover, a prominent pre-peak has also been seen in trilayer nickelates R4Ni3O8 (R = La and Pr), which possess the same NiO2 square plane as in the infinite-layer nickelates and an effective 1/3 hole doping21,29.

Figure 3c, d show O K edge and Ni L2,3 edge XAS of infinite-layer Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 films with different thicknesses. The intensity of pre-peak in O K edge generally increases with decreasing thickness due to the decreasing occupancy (more empty states), suggesting the increase of Ni-O hybridization. The Ni L2,3 peak intensity increases and peak position shifts systematically to higher energies as the thickness decreases. This indicates that with decreasing thickness, the Ni 2p core-level electrons have enhanced binding energy, implying a gradual increase of the oxidation state of Ni. The evolution of XAS may be due to the interface and strain effects with decreasing thickness and could be related to the transport properties as shown above. We note here that the observed XAS signal might contain minute contribution from the presence of local secondary phases in thick films and/or a parasitic surface layer. Nevertheless, all XAS features are similar to those for the ultrathin single-phase film, suggesting that the contribution from the secondary phase is negligible.

It has been constructed by the bulk electronic structure calculations that the infinite-layer nickelate possesses multiband structures which show the hole pocket originating from a Ni-\(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital and the electron pockets from the rare-earth element 5dxy and \(5{d}_{3{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbitals2. Such multiband pictures are consistent with the observed change of RH in Sr-doped NdNiO2 and PrNiO21,3,4,6. Our observation is that the RH of Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 also changes with the thickness (Fig. 2b), possibly related to the alteration of band structure due to the interface and strain effects.

Discussion

Theoretical calculations suggested the presence of electronic and atomic reconstructions at NdNiO2/SrTiO3 interfaces and the resultant alteration of band structure at the interface13,14,15,16. At the surface and interface, the NiO2 layer bends and Ni is displaced vertically due to atomic reconstruction and/or the presence of residual apical oxygen at the NdO plane. It is expected that as the thickness decreases, the interface and/or strain effects are more pronounced. Likely, the bending of the NiO2 layer causes the overall increase of the c-axis lattice constant, as indicated by the XRD measurement (Fig. 1b). The bending of the NiO2 layer and the resultant tilt of Ni-O bonding causes the extra extraction of the electron from Ni to O. This is consistent with our XAS measurement that the oxidation state of Ni increases as the thickness decreases (Fig. 3b, d). Moreover, it has been revealed that the multiband structures become more pronounced at the interface, for example, the mixture of \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) states are present near Fermi level at the interface, causing extra electron pockets13,14,15,16. Therefore, as the thickness decreases, the RH remains negative below 300 K (Fig. 2b). It was proposed that the pairing state of Nd1-xSrxNiO2 changes from (d + is)-wave to d-wave paring as the doping increases30, in line with the crossover of RH from negative to positive sign3,4. Interestingly, the interface/surface effect, which caused the negative RH sign in our result, also induced dominant s-wave paring17 as opposed to d-wave symmetry for the bulk2,31. Overall, even though the Meissner effect is confirmed in the nickelate thin films, the interfacial effects due to the atomic reconstruction play an important role in the modification of multiband structures.

Methods

Thin film growth and reduction

The perovskite Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO3 thin films with different thicknesses were grown on a TiO2-terminated (001) SrTiO3 (STO) substrate using a pulsed laser deposition (PLD) technique with a 248-nm KrF excimer laser. No capping layer is introduced for all samples. The deposition temperature and oxygen partial pressure PO2 for all samples were 600 °C and 150 mTorr, respectively. The laser energy density on the target surface was set to be 1.8 Jcm−2. After deposition, the samples were annealed for 10 min at 600 °C and 150 mTorr and then cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 8 °C/min. The as-grown samples were cut into pieces with a size of around 2.5 × 5 mm2. The pieces were then embedded with about 0.15 g of CaH2 powder and wrapped in aluminum foil, and then placed into the PLD chamber for reduction. Using the PLD heater, the wrapped samples were heated to 340–360 °C at a rate of 25 °C/min and kept for 80 min, and then cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 25 °C/min.

Electrical and magnetic characterizations

The wire connection for the electrical transport measurement was made by Al ultrasonic wire bonding. The electrical transport and magnetization measurements were performed using a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System and Superconducting Quantum Interference Device Magnetometer, respectively.

X-ray diffraction and absorption spectrocopy

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement was done in the X-ray Diffraction and Development (XDD) beamline at Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS) with an X-ray wavelength of λ = 1.5404 Å. The XAS measurements were performed using linearly polarized X-ray from the Soft X-ray-ultraviolet (SUV) beamline at SSLS, using a total electron yield (TEY) detection method. The incidence angle (90-θ)° of X-rays refers to the normal of the sample surface, which was varied by rotating the polar angle of the sample. The spectra were measured in a grazing-incident alignment (θ = 20°) to obtain better sample signals. The spectra were normalized to the integrated intensity at the tail of the spectra after subtracting an energy-independent background.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy

The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) imaging was carried out at 200 kV using a JEOL ARM200F microscope, and the cross-sectional TEM specimens were prepared by a focused ion beam machine (FEI Versa 3D). All the data of the same thickness are measured from the exact same sample to ensure consistency in comparing the results of various measurements.

Data availability

Data available on request from the authors.

References

Li, D. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624–627 (2019).

Botana, A. S., Bernardini, F. & Cano, A. Nickelate superconductors: an ongoing dialog between theory and experiments. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 132, 618–627 (2021).

Li, D. et al. Superconducting dome in Nd1−xSrxNiO2 infinite layer films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 027001 (2020).

Zeng, S. et al. Phase diagram and superconducting dome of infinite-layer Nd1−xSrxNiO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 147003 (2020).

Gu, Q. et al. Single-particle tunneling spectrum of superconducting Nd1-xSrxNiO2 thin films. Nat. Commun. 11, 6027 (2020).

Osada, M., Wang, B. Y., Lee, K., Li, D. & Hwang, H. Y. Phase diagram of infinite layer praseodymium nickelate Pr1−xSrxNiO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 121801 (2020).

Wang, B. Y. et al. Isotropic Pauli-limited superconductivity in the infinite-layer nickelate Nd0.775Sr0.225NiO2. Nat. Phys. 17, 473–477 (2021).

Gao, Q., Zhao, Y., Zhou, X. & Zhu, Z. Preparation of superconducting thin film of infinite-layer nickelate Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2. Chinese Phys. Lett. 38, 077401 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Negligible oxygen vacancies, low critical current density, electric-field modulation, in-plane anisotropic and high-field transport of a superconducting Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2/SrTiO3 heterostructure. Rare Metals 40, 2847–2854 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Absence of superconductivity in bulk Nd1−xSrxNiO2. Commun. Mater. 1, 16 (2020).

Wang, B. X. et al. Synthesis and characterization of bulk Nd1-xSrxNiO2 and Nd1-xSrxNiO3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 084409 (2020).

He, C. et al. Synthesis and physical properties of perovskite Sm1-xSrxNiO3 (x = 0, 0.2) and infinite-layer Sm0.8Sr0.2NiO2 nickelates. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 265701 (2021).

Geisler, B. & Pentcheva, R. Fundamental difference in the electronic reconstruction of infinite-layer versus perovskite neodymium nickelate films on SrTiO3 (001). Phys. Rev. B 102, 020502 (2020).

He, R. et al. Polarity-induced electronic and atomic reconstruction at NdNiO2/SrTiO3 interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 102, 035118 (2020).

Bernardini, F. & Cano, A. Stability and electronic properties of LaNiO2/SrTiO3 heterostructures. J. Phys. Mater. 3, 03LT01 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Similarities and differences between nickelate and cuprate films grown on a SrTiO3 substrate. Phys. Rev. B 102, 195117 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Surface s-wave superconductivity for oxide-terminated infinite-layer nickelates, https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.06009 (2020).

Bisogni, V. et al. Ground-state oxygen holes and the metal-insulator transition in the negative charge-transfer rare-earth nickelates. Nat. Commun. 7, 13017 (2016).

Hepting, M. et al. Electronic structure of the parent compound of superconducting infinite-layer nickelates. Nat. Mater. 19, 381–385 (2020).

Goodge, B. H. et al. Doping evolution of the Mott–Hubbard landscape in infinite-layer nickelates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2007683118 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Large orbital polarization in a metallic square-planar nickelate. Nat. Phys. 13, 864–869 (2017).

Zaanen, J., Sawatzky, G. & Allen, J. Band gaps and electronic structure of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 418 (1985).

Chen, C. et al. Electronic states in La2−xSrxCuO4+δ probed by soft x-ray absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 104 (1991).

Zhang, F. C. & Rice, T. M. Effective hamiltonian for the superconducting Cu oxides. Phys. Rev. B. 37, 3759–3761 (1988).

Lee, K. W. & Pickett, W. Infinite-layer LaNiO2: Ni1+ is not Cu2+. Phys. Rev. B 70, 165109 (2004).

Jiang, M., Berciu, M. & Sawatzky, G. A. Critical nature of the Ni spin state in doped NdNiO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 207004 (2020).

Rossi, M. et al. Orbital and spin character of doped carriers in infinite-layer nickelates, Phys. Rev. B 104, L220505 (2021).

Meyers, D. et al. Zhang-Rice physics and anomalous copper states in A-site ordered perovskites. Sci. Rep. 3, 1834 (2013).

Lin, J. Q. et al. Strong superexchange in a d9-δ Nickelate revealed by resonant inelastic X-Ray scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 087001 (2021).

Wang, Z., Zhang, G. M., Yang, Y. F. & Zhang, F. C. Distinct pairing symmetries of superconductivity in infinite-layer nickelates. Phys. Rev. B. 102, 220501 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Robust dx2−y2-wave superconductivity of infinite-layer nickelates. Phys. Rev. B. 101, 060504(R) (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A*STAR) under its Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering (AME) Individual Research Grant (IRG) (A1983c0034). The authors also acknowledge partial support from the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Singapore under the Tier 2 Grant (Project no. T2EP50121-0039) and the Singapore National Research Foundation (NRF) under the Competitive Research Programs (CRP Grant No. NRF-CRP15-2015-01). P.Y. is supported by Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS) via NUS Core Support C-380-003-003-001. The authors would also like to acknowledge the SSLS for providing the facility necessary for conducting the research. The Laboratory is a National Research Infrastructure under the National Research Foundation (NRF) Singapore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W.Z. and A.A. conceived the project. S.W.Z. prepared the thin films and conducted the electrical and magnetic measurements with the assistance from K.H., Z.H., Y.C., L.E.C., D.Y.W., Z.T.Z. and Z.S.L. S.W.Z., P.Y., C.S.T. and X.M.Y. conducted the XRD measurements. X.M.Y., C.Z.D., C.S.T. and A.T.S.W. conducted the XAS measurements. C.J.L. and S.J.P. conducted the STEM measurements. S.W.Z. and A.A. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors have discussed the results and the interpretations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, S.W., Yin, X.M., Li, C.J. et al. Observation of perfect diamagnetism and interfacial effect on the electronic structures in infinite layer Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 superconductors. Nat Commun 13, 743 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28390-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28390-w

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

DNA as a perfect quantum computer based on the quantum physics principles

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Structural transitions, octahedral rotations, and electronic properties of A3Ni2O7 rare-earth nickelates under high pressure

npj Quantum Materials (2024)

-

Atomic scale disorder and reconstruction in bulk infinite-layer nickelates lacking superconductivity

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from CO2 and methanol over a novel CeO2-zeolite Beta composite catalyst

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2024)

-

Resolving the polar interface of infinite-layer nickelate thin films

Nature Materials (2023)