Abstract

Introduction Guidelines on the length of treatment of dental infections with systemic antibiotics vary across different countries. We aimed to determine if short-duration (3-5 days) courses of systemic antibiotics were as effective as longer-duration courses (≥7 days) for the treatment of dental infections in adults in outpatient settings.

Methods We searched Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase, Cochrane, trials registries, Google Scholar and forward and backward citations for studies published between database inception and 30 March 2021. All randomised clinical trials (RCT) and non-randomised trials which compared length of treatment with systemic antibiotics for dental infections in adults in outpatient settings published in English were included.

Results One small RCT met our defined inclusion criteria. The trial compared three-day versus seven-day courses of amoxicillin in adults with odontogenic infection requiring tooth extraction. There was no significant difference between groups in terms of participant-reported pain or clinical assessment of wound healing.

Discussion While a number of observational studies were supportive of shorter-course therapy, only one small RCT concluded that a three-day course of amoxicillin was clinically non-inferior versus seven days for the treatment of odontogenic infection requiring tooth extraction. Limited conclusions on shorter-course therapy can be drawn from this study as all participants commenced amoxicillin two days before tooth extraction which is not common clinical practice. The variability in guidelines for use of antimicrobials in dental infections suggests that guidelines are based on local or national historical practice and indicates the need for further research to determine the optimum length of treatment. RCTs are required to investigate if short-duration courses of antibiotics are effective and to provide evidence to support consistent guidance for dental professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotics are frequently used in general dental practice for the management of odontogenic infections despite evidence that local dental treatment alone is effective.1 Antibiotics should be reserved for dental infections associated with clear signs of systemic infection.2,3 Antibiotic prescribing in general dental practice accounts for approximately 7% of antibiotic prescriptions in primary care4 and so it is important that the unintended consequences of unnecessary prescribing are well understood and strategies are adopted to assure good prescribing practice. Studies report that both qualified dentists and dental students are aware that inappropriate prescribing and overuse of antibiotics contributes to antimicrobial resistance.5,6,7,8,9,10 Despite these findings and the availability of guidelines for antibiotic prescribing for dental infections,2,11,12,13,14,15 high levels of inappropriate prescribing and low adherence to guidelines are reported, with dentists often prescribing antibiotics for longer durations than may be necessary.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29

In general terms duration of antibiotics is influenced by host factors such as, site of infection (antibiotic penetration), presence of foreign bodies and host immunity, bacterial factors such as intrinsic resistance (for example, Pseudomonas species) or acquired resistance such as beta-lactamases, together with the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the antimicrobial agent. The relation between antibiotic exposure duration and antibiotic resistance is unequivocal both at the population level30 and in individual patients.31 Historically, the recommendations for duration of antibiotic treatment in dentistry have been largely arbitrary and based on convenience, five or seven days, with the assumption that this usually balances the theoretical time to 'use enough antibiotic to eliminate the infecting organism' and 'prevent the development of resistance'. However, empirical evidence does not support this and evidence is emerging for many infections for example, community acquired pneumonia, upper urinary tract infections, that shorter courses are nearly always as effective as standard ones.32

Shorter courses of antibiotic therapy reduce antibiotic consumption thereby reducing patient reported adverse effects such as gastrointestinal upset, mucosal candidosis33 and risk of Clostridioides difficile infection34 at the individual level. Over-treating infection is also associated with increased cost and contributes to the emergence of resistance among colonising flora away from the site of the infection which increases selective pressure driving antimicrobial resistance (AMR).35 Ensuring guidelines are underpinned by evidence will optimise antibiotic prescribing and reduce unnecessary use. Examination of guidelines identified that recommendations on length of treatment vary between countries. UK guidelines recommend three days of treatment for pericoronitis and acute necrotising ulcerating gingivitis and up to five days (with review at three days) for apical abscess.2,14 European and US guidelines state that treatment can be given for up to seven days.11,15 Evidence used to underpin guidelines does not appear to focus on treatment duration. A search of Cochrane, Medline and Embase found a systematic review that included some evidence that shorter durations of antibiotic treatment are effective,36 however no systematic reviews of the optimum length of antibiotic treatment for dental infections were found. The objective of this review was to identify and evaluate published evidence assessing the effect of short-duration (3-5 days) compared with longer-duration (≥7 days) courses of antibiotics used for the treatment of dental infections in general practice or outpatient clinics. The outcomes of interest were resolution of infection evaluated by clinician assessment of local wound healing, adenopathy, trismus and fever, patient reported pain intensity and antibiotic-related adverse effects in adults with dental infections.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement 2020.37 The objective, inclusion criteria and methods of analysis were specified in advance and published in a protocol (Prospero CRD42021241767).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were sought for inclusion in the review:

-

1.

Randomised clinical trials (RCT), non-randomised trials

-

2.

Healthy adult (>18 years) human participants undergoing outpatient treatments for dental infections

-

3.

Studies that report antibiotic usage and regime

-

4.

Clearly defined clinical parameters by which diagnosis and resolution of infection is made - clinician assessment of local wound healing, adenopathy, trismus and fever. Patient reported pain intensity evaluated by any validated measure for example, numeric rating scale/visual analogue scale (VAS)

-

5.

Comparison of different lengths of treatment with the same antibiotics

-

6.

Studies that report antibiotics prescribed as adjuvant to surgical treatment

-

7.

Studies that report antibiotics prescribed without surgical treatment.

The following were excluded from the review:

-

1.

Case reports, retrospective cohort studies, systematic reviews, animal trials, letters to editors, in vivo and in vitro studies

-

2.

Incomplete data

-

3.

Studies without a comparative antibiotic treatment group

-

4.

Studies that involve any additional therapy that could affect the outcomes

-

5.

Studies in children

-

6.

Studies that report on inpatient treatment of patients with dental infections.

Search strategy

To identify relevant publications, we searched the Cochrane Library, Ovid Embase, Ovid Medline and Google Scholar electronic databases from inception to 30 March 2021. The search was limited to articles written in English (due to lack of facility for translation). ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Trial Registry Platform were searched for ongoing and unpublished studies. Backwards and forwards searches of selected studies were conducted.

Data collection and analysis

Search results were exported to Endnote and EPPI reviewer. Following removal of duplicates, all titles and abstracts were screened by two authors (LC, NS). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third author (JS). Full text was retrieved for all records deemed to meet the inclusion criteria. The search strategy for all searches is available in Appendix 1. Data from eligible studies was extracted using a tool created for this study. The following information was extracted: author and year, study setting, research methodology (study design, type of infection, type and dose of antibiotic used, duration of treatment), sample size in each group, follow-up period, clinical outcomes. Authors of included studies were contacted for clarification of methodology/results and missing information.

Assessment of methodological quality

Studies selected for critical appraisal were assessed independently by two authors using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised clinical trials. We planned to develop a 'Summary of findings' table for the main outcomes of the review using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) software to assess the quality of evidence.

Data synthesis

We planned to conduct a structured narrative summary of included studies. For dichotomous outcomes such as presence of adenopathy, trismus or fever, we were to calculate risk ratios (RR) plus 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes such as mean VAS scores and body temperature, we were to calculate mean difference (MD) plus 95% CI.

Results

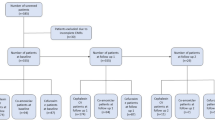

Following removal of duplicates, the searches identified a total of 599 citations. Independent review of the titles and abstracts resulted in retrieval of full text for four potentially relevant publications. Reference lists of potentially eligible studies yielded no further potential studies. Studies were evaluated against the inclusion criteria and one could be included. Figure 1 details the study selection flowchart.

Risk of bias in included studies

One RCT was critically appraised and included in the review. The quality score was 12 indicating overall low risk of bias. The results of the critical appraisal process are presented in Table 1.

Effects of interventions

A summary of the included study is presented in Table 2. The study evaluated clinical efficacy and the susceptibility to amoxicillin of oral streptococci in patients with odontogenic infection requiring tooth extraction and receiving amoxicillin therapy for three or seven days.38 The study sample comprised 81 patients, aged 19-45 years, attending for emergency dental care in three emergency departments in France who were randomly allocated to treatment or control groups. All patients were commenced on oral amoxicillin 1 g twice daily on day 0 and underwent tooth extraction on day 2. Patients in group 1 (n = 42) received amoxicillin for three days followed by a placebo for four days. Patients in group 2 (n = 39) received standard seven-day therapy with amoxicillin. Both patients and dentists were blinded to group allocation for the duration of the study. Fifty-six patients were evaluated on day 9 (n = 29 in group 1 and n = 27 in group 2) and 41 (n = 22 in group 1 and n = 19 in group 2) on day 30 using VAS scale 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain) and patient-reported total ingestion of paracetamol for pain. Treatment response was evaluated with respect to local wound healing, scored by combining local inflammation and sensitivity and the presence of a blood clot. Evaluation of fever was stated as assessment criteria but not reported. The experimental treatment was considered to be non-inferior to the regular treatment if the difference between treatments was less than two points for intensity of pain and wound healing scores and 2 g for the total amount of paracetamol ingested.

The results showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups. Pain intensity in group 1 was 3.5-95% Confidence interval (CI) (3, 6) and in group 2 was 4-95% CI (2, 6). Ingested paracetamol was 5 g 95% CI (1.6 g, 9 g) in group 1 and 4 g 95% CI (1 g, 6 g). Wound healing score was 1-95% CI (1, 2) in both groups and regional adenopathy was observed in one patient in each group. Authors concluded that the similar clinical efficacy observed favoured a reduction in the duration of antibiotic exposure.

Three studies available in English, excluded at full text stage due to lack of a comparison group, advocated early treatment review and efficacy of shorter courses, although duration was not the primary objective of the studies. In the 2015 study by Tancawan and colleagues,39 an early clinical response was observed after two days of treatment with both co-amoxiclav and clindamycin. Adriaenssen40 reported that a three-day course of azithromycin 500 mgs once per day was as effective as a seven-day course of co-amoxiclav 500/125 mgs in resolution of acute periapical abscesses. However, these two antibiotics have vastly different half-lives (azithromycine 2-4 days, amoxicillin six hours) therefore the implication of these results is unclear. Three treatment regimes in patients with systemic involvement in dento-alveolar abscesses at two, three and ten days were investigated (amoxicillin 250 mgs three times daily, clindamycin 150 mgs four times daily or erythromycin 250 mgs four times daily).41 All patients received initial treatment to drain the abscess and at first review 98.6% of patients had normal temperatures and marked resolution of swelling so antibiotics were discontinued. It should be noted that antibiotic doses in this study from 1997 are lower than those used now and routine use of antibiotics after abscess drainage is no longer standard practice. A single published audit of 188 patients suggested that following abscess drainage to remove the cause of infection a three-day antibiotic regime is effective for patients with signs of systemic infection.42

Discussion

One study that met our inclusion criteria was identified. The authors of this study concluded non-inferiority of short course versus longer course amoxicillin for dental infections in a small cohort of adults but with antibiotic treatment two days before tooth extraction. Studies without comparison groups also supported the safety and efficacy of shorter antibiotic treatment durations for dental infections, however the evidence found is not sufficient to determine the safety and efficacy of shorter courses of antibiotics for dental infection, a limitation of current evidence. Variability in global guidelines for antibiotic use in dental infections in respect of the length of treatment suggests that these guidelines are based on local or national standard practice rather than evidence. A review of clinical practice guidelines was not considered within the scope of this piece of work. Not all clinical practice guidelines are evidence based and are not without their limitations including the dependence upon the consensus of experts that compile them.43 We hypothesise that duration of prescribing has evolved empirically based on historical clinical experience and dogma analogous with some other areas of infection management.

Given the need to reduce AMR and unnecessary antibiotic prescribing, research such as RCTs investigating the safety and efficacy of short courses of antibiotics versus standard treatment for appropriate dental infections is recommended. Dental clinical trials have improved in quality with time, but many still suffer from bias and unfavourable quality assessment.44 Research agenda priorities have been identified as an area across health care that need re-evaluation, and dentistry is no exception. Dental research tends to be driven by the interests of the researchers and their area of expertise.45 A UK patient and clinician research initiative in 2018 did not identify antibiotics as a priority for dental research, nor did a study in the Netherlands.45,46 Regrettably, it would seem that in a competing landscape of limited resources, clinical trials of antibiotics in dentistry are not perceived a priority. Reflecting on the paucity of high quality RCTs for the optimal management of infection in out-patient dental practice we hypothesise that the reasons are multi-factorial and range from a lack of incentive from pharmaceutical industries and funding bodies, to the demise in the dental speciality clinical oral microbiology over the last two decades leading to a smaller pool of suitably qualified and experienced practitioners in infection management to provide expert guidance in the planning and execution of suitable studies.

Shorter courses of antibiotics have been shown to be effective in the treatment of other common infections. A systematic review investigating antibiotic treatment length in hospitalised patients with common infections including pneumonia, upper urinary tract infection and intra-abdominal infection concluded that shorter courses are safe and can achieve resolution of common infections without adverse effects on mortality or recurrence.47 More recently a RCT of three days versus >5 days treatment duration in pneumonia showed non-inferiority.48 There is therefore a growing body of evidence across a range of bacterial infections which supports shorter course antibiotic therapy than has been traditionally used in hospitalised patients.49

Conclusion

In conclusion, a clinical audit of 188 patients with dental infection and signs of systemic involvement treated by abscess drainage and a three-day antibiotic regime demonstrated no adverse effect. No robust evidence in the form of RCTs supporting durations of antibiotic treatment for dental infections within current national guidelines was found. Further research in this area is required to inform guidelines and provide evidence to support more consistent practice. Exploring a move to shorter duration of treatment has potential benefits for patients and for tackling the threat of AMR.

References

Matthews D C, Sutherland S, Basrani B. Emergency management of acute apical abscesses in the permanent dentition: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Dent Assoc 2003; 69: 660.

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Drug prescribing for dentistry: Dental clinical guidance. 3rd ed. Dundee: SDCEP, 2016.

Aminoshariae A, Kulild J C. Evidence-based recommendations for antibiotic usage to treat endodontic infections and pain: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2016; 147: 186-191.

National Services Scotland. Scottish One Health Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: Annual Report. 2020. Available at https://www.nss.nhs.scot/publications/scottish-one-health-antimicrobial-use-and-antimicrobial-resistance-in-2019/ (accessed October 2021).

Angel Fastina M, Geetha R. Knowledge and awareness about antibiotic policy among dentists. Drug Invent Today 2019; 11: 2531-2533.

Jain M R, Ganapathy D, Sivasamy V. A survey on knowledge, attitude, and perception of antibiotic resistance and usage among dental students. Drug Invent Today 2020; 13: 465-469.

Martin-Jimenez M, Martin-Biedma B, Lopez-Lopez J et al. Dental students' knowledge regarding the indications for antibiotics in the management of endodontic infections. Int Endod J 2018; 51: 118-127.

Ramadan A M, Al Rikaby O A, Abu-Hammad O A, Dar-Odeh N S. Knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic prescribing among dentists in Sudan. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatr Clin Integr 2019; DOI: 10.4034/PBOCI.2019.191.17.

Srinivasan S, Pradeep S. The attitude of dentists towards the prescription of antibiotics during endodontic treatment - a questionnaire based study. Int J Pharm Technol 2016; 8: 15895-15900.

Wehr C, Cruz G, Young S, Fakhouri W D. An insight into acute pericoronitis and the need for an evidence-based standard of care. Dent J (Basel) 2019; DOI: 10.3390/dj7030088.

Lockhart P B, Tampi M P, Abt E et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on antibiotic use for the urgent management of pulpal-and periapical-related dental pain and intraoral swelling: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2019; DOI: 10.1016/j.adaj.2019.08.020.

Palmer N. Antimicrobial prescribing in dentistry: good practice guidelines. 3rd ed. London: FGDP, 2020.

American Association of Endodontists. AAE Position Statement: AAE Guidance on the Use of Systemic Antibiotics in Endodontics. J Endod 2017; 43: 1409-1413.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial Prescribing Guidelines. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/published?ngt=Antimicrobial%20prescribing%20guidelines&ndt=Guidance (accessed October 2021).

Segura-Egea J J, Gould K, Şen B H et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: the use of antibiotics in endodontics. Int Endod J 2018; 51: 20-25.

Vasudavan S, Grunes B, McGeachie J, Sonis A L. Antibiotic prescribing patterns among dental professionals in Massachusetts. Pediatr Dent 2019; 41: 25-30.

Sturrock A, Landes D, Robson T, Bird L, Ojelabi A, Ling J. An audit of antimicrobial prescribing by dental practitioners in the north east of England and Cumbria. BMC Oral Health 2018; DOI: 10.1186/s12903-018-0682-4.

Silva M, Paulo M, Cardoso M et al. The use of systemic antibiotics in endodontics: A cross-sectional study. Revista Portuguesa Estomatologia Medicina Dentaria Cirurgia Maxilofacial 2017; 58: 205-211.

Maslamani M, Sedeqi F. Antibiotic and analgesic prescription patterns among dentists or management of dental pain and infection during endodontic treatment. Med Princ Pract 2018; 27: 66-72.

Krishnaa K, Ganapathy D, Bennis M A. Status on the use of antibiotics in endodontic infections among dentists. Drug Invent Today 2020; 14: 562-567.

Inchara R, Ganapathy D, Kiran Kumar P. Preference of antibiotics in pediatric dentistry. Drug Invent Today 2019; 11: 1495-1198.

Bjelovucic R, Par M, Rubcic D, Marovic D, Prskalo K, Tarle Z. Antibiotic prescription in emergency dental service in Zagreb, Croatia- a retrospective cohort study. Int Dent J 2019; 69: 273-280.

Baudet A, Kichenbrand C, Pulcini C et al. Antibiotic use and resistance: a nationwide questionnaire survey among French dentists. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2020; 39: 1295-1303.

Al-Zobaidy M A H J. Evaluation of drug prescription pattern among Iraqi dentists in Babylon city. J Global Pharma Tech 2019; 11(2 Supplement): 204-210.

Ahsan S, Hydrie M Z I, Naqvi S M Z H et al. Antibiotic prescription patterns for treating dental infections in children among general and pediatric dentists in teaching institutions of Karachi, Pakistan. PLoS One 2020; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235671.

Krah-Sinan A, Adou-Assoumou M, Adou J, Dossahoua K T, Faye D, Mansilla E. Antibiotic therapy in endodontics: a survey from dental surgeons in Ivory Coast. Giornale Italiano Endodonzia 2019; 33: 21-26.

Koyuncuoglu C Z, Aydin M, Kirmizi N I et al. Rational use of medicine in dentistry: do dentists prescribe antibiotics in appropriate indications? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 73: 1027-1032.

Bolfoni M R, Pappen F G, Pereira-Cenci T, Jacinto R C. Antibiotic prescription for endodontic infections: a survey of Brazilian Endodontists. Int Endod J 2018; 51: 148-156.

Asmar G, Cochelard D, Mokhbat J, Lemdani M, Haddadi A, Ayoubz F. Prophylactic and therapeutic antibiotic patterns of Lebanese dentists for the management of dentoalveolar abscesses. J Contemp Dent Pract 2016; 17: 425-433.

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M, ESAC Project Group. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 2005; 365: 579-587.

Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay A D. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.c2096.

Dawson-Hahn E E, Mickan S, Onakpoya I et al. Short-course versus long-course oral antibiotic treatment for infections treated in outpatient settings: a review of systematic reviews. Fam Pract 2017; 34: 511-519.

Vaughn V M, Flanders S A, Snyder A et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171: 153-163.

Bye M, Whitten T, Holzbauer S. Antibiotic prescribing for dental procedures in community-associated Clostridium difficile cases, Minnesota, 2009-2015. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofx162.001.

Spellberg B. The new antibiotic mantra - 'shorter is better'. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 1254-1255.

Teoh L, Cheung M C, Dashper S, James R, McCullough M J. Oral antibiotic for empirical management of acute dentoalveolar infections - a systematic review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021; DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics10030240.

Page M J, McKenzie J E, Bossuyt P M et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

Chardin H, Yasukawa K, Nouacer N et al. Reduced susceptibility to amoxicillin of oral streptococci following amoxicillin exposure. J Med Microbiol 2009; 58: 1092-1097.

Tancawan A L, Pato M N, Abidin K Z et al. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for the treatment of odontogenic infections: a randomised study comparing efficacy and tolerability versus clindamycin. Int J Dent 2015; DOI: 10.1155/2015/472470.

Adriaenssen C F. Comparison of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of azithromycin and co-amoxiclav in the treatment of acute periapical abscesses. J Int Med Res 1998; 26: 257-265.

Martin M V, Longman L P, Hill J B, Hardy P. Acute dentoalveolar infections: an investigation of the duration of antibiotic therapy. Br Dent J 1997; 183: 135-137.

Ellison S J. An outcome audit of three-day antimicrobial prescribing for the acute dentoalveolar abscess. Br Dent J 2011; 211: 591-594.

Woolf S H, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999; 318: 527-530.

Saltaji H, Armijo-Olivo S, Cummings G G, Amin M, Flores-Mir C. Randomized clinical trials in dentistry: Risks of bias, risks of random errors, reporting quality, and methodologic quality over the years 1955-2013. PLoS One 2017; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190089.

van der Wouden P, Shemesh H, van der Heijden G J M G. Research priorities for oral healthcare: agenda setting from the practitioners' perspective. Acta Odontol Scand 2021; 79: 451-457.

National Institute for Health Research. The TOP 10 Priorities for oral and dental health research. 2017. Available at https://oralanddentalhealthpsp.wordpress.com/participate/ (accessed October 2021).

Royer S, DeMerle K M, Dickson R P, Prescott H C. Shorter versus longer courses of antibiotics for infection in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med 2018; 13: 336-342.

Dinh A, Ropers J, Duran C et al. Discontinuing β-lactam treatment after 3 days for patients with community-acquired pneumonia in non-critical care wards (PTC): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2021; 397: 1195-1203.

Spellberg B. Shorter is better. 2021. Available at https://www.bradspellberg.com/shorter-is-better (accessed October 2021).

Funding

The Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group receives funding from the Scottish Government. No specific funding was provided for this work. Registration number: Prospero CRD42021241767.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. Cooper, J. Sneddon, R. A. Seaton and A. Smith designed the study. L. Cooper and J. Sneddon drafted the manuscript. L. Cooper and N. Stankiewicz completed the literature search, data collection and quality assessment, analysis and synthesis. J. Sneddon, N Stankiewicz, A. Smith and R. A. Seaton critically reviewed and revised the draft manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, L., Stankiewicz, N., Sneddon, J. et al. Optimum length of treatment with systemic antibiotics in adults with dental infections: a systematic review. Evid Based Dent (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-022-0801-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-022-0801-6

- Springer Nature Limited