Abstract

Background Tertiary prevention is still an integral part of a child's healthcare. In community dental service (CDS), we aim to try to restore carious primary teeth in young children as a means of caries control.

Aim To assess the survival rates of individual carious primary molars within CDS, based on the type of dental interventions.

Design Retrospective observational study.

Methods Fifty patients' notes were reviewed, and patients were selected using a defined protocol. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the survival curves.

Results Out of 251 teeth, the estimated survival rates of teeth restored with stainless steel crowns (SSC) was the highest at 46.7 months, GIC-restored teeth at 45.8 months and unrestored teeth at 18.2 months. There was no correlation seen between the survival rates and the number of further interventions required. The difference between the survival rates of teeth restored with GIC, SSC and unrestored was statistically significant (p <0.05). There was minimal use of SSCs within this sample.

Conclusion Our present findings indicate that restored teeth have higher survival rates than unrestored teeth. However, it must be emphasised that restorative treatment may not always be feasible and other factors should be considered in the treatment planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Provides a retrospective analysis on the survival rates of primary carious teeth within community dental services in Wales.

-

Highlights the use of radiographs is essential in treatment planning.

-

Emphasises the need for primary and secondary prevention to reduce disease activity.

Introduction

Caries is a preventable disease, but the risk of caries is associated with socioeconomic factors. In response, the Welsh Government had implemented a national programme called 'Designed to Smile', which involves the provision of primary caries prevention within schools. However, not all schools are involved in this programme. The dental caries experience in Wales had improved from 1.98 in 2007/08 to 1.22 in 2015/16, with the most deprived population showing the largest reduction in caries prevalence by 15%.1 However, there is still scope for further improvement. Filipponi et al.2 suggested that equity to dental care access based on needs is to be prioritised.

Tertiary prevention in the primary dentition is still an integral part of child healthcare. It helps to prolong the retention of primary teeth as a means of pain relief and caries control until tooth exfoliation. Roberts et al.3 found that stainless steel crowns (SSC)/Hall technique crowns continued to prove very successful for restoring teeth with larger cavities and teeth which had pulpal therapy; while resin-modified glass-ionomer cement (RMGIC) showed promising survival rates for teeth with small cavities. In addi

tion, there is evidence to support atraumatic restorative technique (ART) as a successful treatment option for young children who are unable to cope with definitive dental restorative procedures.4 Hence, ART can be an effective method to treat carious primary teeth until their natural exfoliation or a definitive restoration can be placed. A survey by Tickle et al.5 reported a variation in approaches to management of caries in deciduous teeth among GDPs and paediatric specialists. It is emphasised that other aspects such as medical, social, and dental factors need to be considered during treatment planning. Hence, the decision to treat carious primary molars is dependent on the clinician's judgement, led by patient factors.

The aim of this study was to assess the survival rates of treated primary molars based on the type of intervention provided, including no treatment. Dental restorations can act as intermediate pain relief and caries control until the tooth exfoliates. In addition, this aims to encourage general dental practitioners (GDPs) to carry out restorative treatment for young children, if feasible.

Materials and methods

A retrospective observational study was carried out in Central Clinic, CDS, Swansea. These patients were referred by GDPs, health visitors and schools due to lack of access to dental treatment and dental phobia. The data were collected by reviewing the notes via the SOEL system (record keeping software) from 50 patients seen in the clinic starting 1 January 2016. The inclusion criteria were that the patients should be seen and treated under eight years of age and were annual dental attenders. Patients who were medically compromised or had learning difficulties were excluded from data collection. The IBM SPSS statistics package was used to calculate the estimated survival rates of these teeth, using the Kaplan-Meier test.6 The search protocol used for our data collection was modified from the protocol used by Levine et al. (2002) (Fig. 1).7

Patient selection criteria. Modified from protocol used by Levine et al.7 Approaches taken to the treatment of young children with carious primary teeth: a national cross-sectional survey of general dental practitioners and paediatric specialists in England. Br Dent J 2007; 203: E4, Springer Nature

Data parameters

-

1.

Data on the initial date of caries diagnosis

-

2.

Presence and absence of symptoms

-

3.

Date and type of initial dental intervention

-

4.

Number of dental interventions on the same tooth, post-initial treatment

-

5.

Date and outcome of the tooth at last recall visit or tooth loss (final outcome).

Data analysis

Tooth survival rates = (date of final outcome of tooth) - (date of initial diagnosis/intervention). Comparison of tooth survival rates was based on the type and number of interventions, patients' cooperation and the presence of symptoms

Results

There was a total of 251 teeth included in this study. On initial caries diagnosis, 49.8% (n = 125) of teeth initially presented with single-surface caries, 42.2% (n=106) of teeth had two-surface caries, and the remainder (n = 20) had gross caries. Furthermore, 85.6% (n = 215) of teeth were restored with GIC, 12.0% (n = 30) were unrestored, 1.6% (n = 4) restored with SSCs, and 0.8% (n = 2) with zinc oxide eugenol cement. The age group of patients treated in this sample was between four- and seven-years-old. At the last recall appointments, 49% of all teeth were present. We are unable to reassess these patients as they were discharged from CDS.

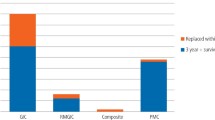

Tooth survival rates based on intervention

The Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to measure the estimated survival rates of these restored teeth. The estimated survival rates were the highest for SSC restored teeth at 46.7 months, GIC restored teeth at 45.8 months and the lowest was unrestored teeth at 18.2 months. Table 1 shows the estimated means and median for survival time and Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. The difference between the survival rates of teeth restored with GIC, SSC and unrestored was statistically significant (p <0.05).

Tooth survival rates based on number of interventions

There is no correlation seen between the number of dental interventions required post-initial treatment and the tooth survival rates of teeth as well as the final outcomes of the restored teeth. There were multiple factors for the variation in the number of interventions for GIC restored teeth. This includes failed restorations, new carious lesions, pain and recurrent caries as well as the operator's clinical decision. SSC-restored teeth did not need any further intervention in this study. Only three patients had teeth initially treated with SSC.

Tooth survival rates based on patient cooperation

Patients with poor cooperation were more likely to have teeth extracted under general anaesthesia (GA) compared to children with good and fair cooperation.

The effects of symptoms on the tooth survival rates

Table 2 shows the comparison of survival rates between symptomatic and asymptomatic teeth. Of unrestored symptomatic teeth, 77% were extracted under GA and their survival rate was less than a year. On the contrary, 29% of symptomatic GIC-restored teeth were extracted under GA but they survived up to two years. The other 23% of symptomatic GIC-restored teeth were extracted under local anaesthesia and their survival rate was up to five years. Hence, symptomatic restored teeth have a better tooth prognosis compared to their unrestored counterpart.

Furthermore, 65% of unrestored asymptomatic teeth were extracted under GA and survived up to three years; whereas 5% of GIC-restored asymptomatic teeth needed extraction under GA, but their survival rates were less than two years. However, 69% of GIC-restored asymptomatic teeth were shown to have survived for more than two years. Unrestored asymptomatic teeth have poorer tooth prognosis than their restored counterparts. They can be left unrestored to exfoliate uneventfully, provided the cases are carefully selected.8 These figures were affected by patients' and parents' cooperation, clinicians' decision-making and the severity of tooth symptoms. Only 16% of the teeth required pulpal therapy and their survival rates were variable between two months and 55 months.

Discussion

In this study, it was observed that asymptomatic unrestored teeth were extracted under GA along with symptomatic teeth to avoid any repeat dental GA. This may account for the low survival rates of unrestored teeth. In addition, it was noted that there was a variation in the management of caries in primary molars among clinicians. The minimal use of stainless-steel crowns in this study highlighted the need for training in their use within the department. Based on the data, the cohort of patients seen had high caries activity which may be associated with socioeconomic status. This is another factor for the high drop-out rate due to failure to keep dental appointments.

There were several limitations identified in this retrospective study. There were no dental radiographs available to fully assess the extent of carious lesions or presence of pulpal pathology. The record keeping provided insufficient information on the history of pain and caries removal procedure (either full or partial caries removal). The referral letters for XGA were difficult to retrieve, as they were not recorded electronically. It was also difficult to assess the level of cooperation from the notes as only history of poor cooperation was previously recorded. Moreover, there is a risk of overestimating the survival rates of these teeth as we are unable to identify exactly when the tooth was exfoliated by a period of three to six months, based on the recall period. There was a high drop-out rate of 49% as these patients were discharged from the department. There was also no follow-up available on the remaining teeth. Additionally, the data sample was very small and the number of SSCs placed was low.

There are a limited number of retrospective studies on tooth survival rates of primary molars. Levine et al.7 reported that 82% of unrestored deciduous teeth exfoliated uneventfully. Their average survival rates were about 3.6 years, which was much higher than our study which was at 1.5 years. In another retrospective study by Tickle et al.,9 87.6% of unrestored single surface carious lesions and 78.4% of two-surface lesions in primary molars were found to exfoliate asymptomatically. There was no record of survival times in that study. In comparison, our present findings observed tooth exfoliation in only 7% of unrestored teeth.

There are several randomised control trials comparing the survival rates of primary teeth based on interventions. Table 3 shows a comparison of the estimated survival rates of teeth restored with GIC, based on their survival period. Hilgert et al.10 reported that there is no difference in the survival rates of intact and defective restorations in primary molars. Mijan et al.11 investigated the survival rates of teeth treated according to three different protocols; conventional restorative treatment (CRT), atraumatic restorative technique (ART) and ultra-conservative technique (UCT), and observed that there was no difference in their 3.5 years survival rates. In these two studies, primary prevention was another focus of treatment as the children had daily supervised oral hygiene instructions from dental assistants. In addition, all the treatments were carried out by specialist paediatric dentists. Hence, this may have accounted for the higher tooth survival rates in those studies when compared to the current study. In the present study, there were multiple factors leading to the high percentage of teeth being extracted. The factors include patients' and parents' cooperation, severity of symptoms and the clinician's decision.

Hence, these factors should be considered in initial treatment planning. Clinicians should be encouraged to attempt to delay or avoid the need for GA by restoring symptomatic and asymptomatic primary molars depending on level of disease activity. Dental anxiety is multifactorial and the treatment of caries in young patients does not ultimately result in dental anxiety unless their experience is traumatic.12 There are other options available such as cognitive behavioural therapy and conscious sedation techniques13,14 in the management of dentally anxious young patients.

Conclusion

Our present findings demonstrate that restored teeth have higher tooth survival rates than unrestored teeth. We must point out that our findings cannot be generalised to the whole population because the survival rates are tooth-centric, and the study sample is too small. Other factors should be considered to predict the practicality and success of the treatment. There is a need for further research in the analysis of tooth survival to help clinicians in their decision-making to restore carious teeth or monitor them. The decision to leave carious teeth unrestored should be justified after the consideration of patient factors.

GA should not be limited to medically compromised children, as it may be a good option for comprehensive dental treatment in healthy children where extensive dental work is required or where there is a need dictated by the severity of symptoms. However, these patients should be encouraged to return for regular dental checks for primary preventative care which is in line with the Delivering better oral health toolkit.15 Improvements are required in easy access dental care and health promotion programmes targeted towards the most deprived areas of the population.2

References

Morgan M, Monaghan N. Picture of Oral Health 2017: Dental caries in 5 year olds (2015/16). 2017. Available at https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/__data/assets/word_doc/0019/801820/Picture-of-Oral-Health-2017_final-report-for-WOHIU-website.docx (accessed April 2019).

Filipponi T, Richards W, Coll A M. Oral health knowledge, perceptions and practices among parents, guardians and teachers in South Wales, UK: A qualitative study. Br Dent J 2018; 224: 517-522.

Roberts J F, Attari N, Sherriff M. The survival of resin modified glass ionomer and stainless steel crown restorations in primary molars, placed in a specialist paediatric dental practice. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 427-431.

Raggio D P, Hesse D, Lenzi T L, Guglielmi C A, Braga M M. Is Atraumatic restorative treatment an option for restoring occlusoproximal caries lesions in primary teeth? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent 2013; 23: 435-443.

Tickle M, Threlfall A G, Pilkington L, Milsom K M, Duggal M S, Blinkhorn A S. Approaches taken to the treatment of young children with carious primary teeth: a national cross-sectional survey of general dental practitioners and paediatric specialists in England. Br Dent J 2007; 203: E4.

Goel M K, Khanna P, Kishore J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J Ayurveda Res 2010; 1: 274-278.

Levine R S, Pitts N B, Nugent Z J. The fate of 1: 587 unrestored carious deciduous teeth: a retrospective general dental practice based study from northern England. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 99-103.

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Prevention and Management of Dental Caries in Children: Dental Clinical Guidance. 2nd ed. 2018. Available at http://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SDCEP-Prevention-and-Management-of-Dental-Caries-in-Children-2nd-Edition.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Tickle M, Milsom K, King D, Kearney-Mitchell P, Blinkhorn A. The fate of the carious primary teeth of children who regularly attend the general dental service. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 219-223.

Hilgert L A, de Amorim R G, Leal S C, Mulder J, Creugers N H, Frencken J E. Is high-viscosity glass-ionomer-cement a successor to amalgam for treating primary molars? Dent Mater 2014; 30: 1172-1178.

Mijan M, de Amorim R G, Leal S C et al. The 3.5-year survival rates of primary molars treated according to three treatment protocols: a controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2014; 18: 1061-1069.

Finucane D. Rationale for restoration of carious primary teeth: a review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2012; 13: 281-292.

Galeotti A, Garret Bernardin A, D'Antò V et al. Inhalation Conscious Sedation with Nitrous Oxide and Oxygen as Alternative to General Anaesthesia in Precooperative, Fearful, and Disabled Paediatric Dental Patients: A Large Survey on 688 Working Sessions. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 7289310.

Porritt J, Rodd H, Morgan A et al. Development and Testing of a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Resource for Children's Dental Anxiety. JDR Clin Trans Res 2017; 2: 23-37.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 3rd ed. 2017. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf (accessed April 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chieng, C., Mohan, R. & Hill, V. Management of carious primary molars within the community dental setting in Wales: a retrospective observational study. Br Dent J 226, 687–691 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0248-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0248-0

- Springer Nature Limited