Abstract

Study design

Descriptive phenomenological approach.

Objectives

This study explored the lived experience of sexuality for men after spinal cord injury (SCI) and described the current state of tools and resources available to assist with sexual adjustment from the perspective of men living with SCI.

Setting

Men living in the community in Ontario, Canada.

Methods

Six men (age 24–49 years) with complete or incomplete SCI (C4-T12; <1–29 years post injury) participated in one individual, in-depth, standardized, open-ended interview (68–101 min). Analysis was conducted using Giorgi’s method, and involved within case analysis followed by cross-case analysis.

Results

All participants reported that resources available to support sexual adjustment after SCI were inadequate, and the majority of men felt their healthcare providers lacked knowledge regarding, and comfort discussing sexuality after SCI. Men reported sexuality was not a priority of the rehabilitation centers and felt that healthcare providers did not understand the importance of addressing sexuality. Existing resources were described as too clinical and not necessarily relevant given changes in sensation and mobility post injury. Participants provided recommendations for the effective delivery of relevant sexual education information.

Conclusions

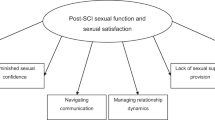

To improve quality of life for men after SCI, suitable resources must be available to support sexual rehabilitation post injury. Future research should focus on developing strategies to facilitate discussions about sexuality between individuals with SCI and healthcare providers, and on developing resources that are effective and relevant for these men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 86,000 people in Canada live with a spinal cord injury (SCI), half of which reside in the province of Ontario [1, 2]. While SCI will affect many body functions and sensations, an SCI does not eliminate sexual feelings or the need for physical and emotional sexual intimacy [3]. Sexuality and quality of life (QOL) are interwoven and reinforce one another, and an active and satisfying sexual life after SCI is associated with improvements in overall adjustment and QOL [4, 5]. A study by Anderson et al. [6] found that 83.2% of participants felt their SCI had altered their sexual sense of self, and 82.9% felt that improving sexual function was important for improving QOL. Despite the importance of sexual health and sexual education for individuals after SCI, there is an unmet need for sexual rehabilitation information, as well as numerous challenges for patient-provider discussions regarding sexuality [7, 8]. All of the participants in a study by Basson et al. [9] felt that they had received inadequate guidance regarding sexuality from their healthcare providers. Patients and healthcare providers alike have reported difficulties regarding sexual education for individuals with disabilities. Patients reported that healthcare providers lacked knowledge when it came to sexuality for people with disabilities and felt their healthcare providers were too shy to have the discussion with them [7]. From the healthcare provider perspective, barriers included a lack of time, lack of knowledge, lack of clarity regarding whose job it was to discuss topics of sexuality, their own attitudes about sexuality, and the patient’s lack of readiness to discuss sexuality [10, 11].

Furthermore, existing resources have predominantly focused on the physical aspects of sexuality including erectile dysfunction and ejaculatory dysfunction [6]. However, recent work suggests that due to changes in the body resulting from SCI, men may adopt a new perspective on sexuality placing less emphasis on those physical factors and more importance on psychological and emotional components of sexuality including connection and intimacy with a partner and exploration of novel ways to experience sexuality beyond the traditional view of sex as a purely penetrative experience [12]. This study explored the lived experience of sexuality for men after SCI and described the current state of tools and resources available to assist with sexual adjustment from the perspective of men living with SCI (Tables 1 and 2).

Methods

Data for this manuscript were collected as part of a larger study examining the lived sexual experiences for men after SCI. A paper has recently been published from that data which discussed the evolving meaning of sexuality for men after SCI [12]. The present paper will report the health services information that was uncovered during that investigation.

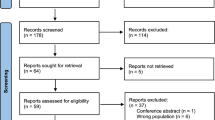

Using Giorgi’s descriptive, phenomenological approach [13], the lived experience of sexuality for men with SCI was explored. Phenomenological studies typically employ a small number of participants that allow for a deep and detailed exploration of the topic under investigation [14]. A minimum of three participants and a maximum of ten have been recommended for this type of inquiry [15, 16]. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were male, between the ages of 18 and 50, living in Canada with an SCI of any level or classification and were able to communicate in English. Due to the novel, and therefore exploratory nature of this research, maximum variation was applied when establishing the inclusion criteria. Despite utilizing a convenience sampling approach, the purposefully broad inclusion criteria enabled a sample of participants that varied in terms of injury and demographic characteristics. This provided a broad view of the issues that exist regarding sexuality in this population. Patterns emerging from varied conditions are valuable in that they capture the core experiences of a phenomenon across contexts and identify factors of particular interest [14]. Recruitment information was posted in relevant SCI groups on social media platforms, and any man who saw the post and was interested in the study was instructed to contact the researcher for more information. The first six men to respond were screened for eligibility, and upon determination that they met inclusion criteria, they were invited to participate. All of the men who inquired about the study and who were eligible to participate agreed to be interviewed.

Rich and detailed descriptions were obtained by means of one-to-one interviews conducted with individuals who had first-hand lived experience with the phenomenon [17]. Participants selected a pseudonym by which they would be referred to throughout the investigation, and each participant completed one in-depth confidential telephone interview (68–101 min; mean time 81 min). Interviews followed a standardized, open-ended approach combined with interview guide approach (see Supplementary Appendix A for interview guide). The same key questions were asked in each interview ensuring conformity in the issues that were discussed with each participant while also allowing for exploration into new and relevant topics that were not anticipated, but which surfaced through discussion [14]. Interview questions were developed based on the previous literature and covered the six question types that have been suggested by Patton [13]: demographic, experience/behavior, knowledge, sensory, feeling/emotion, and opinion/value [14]. Probing questions were used to further investigate certain topic areas. Interviews were audio recorded using a Sony ICD-PX370 digital voice recorder and were transcribed verbatim. Field notes were documented during each interview. Data were analyzed throughout data collection using Giorgi’s method [13] and informed subsequent interviews [18]. After all interview transcripts were analyzed individually, a cross-case analysis was performed and interviews were analyzed together to shed light on the phenomenon across various contexts and relationships. Themes between transcripts were identified using Giorgi’s method [13] and were supported by direct quotations from participants' transcripts. Data were analyzed independently by two researchers and discussed until consensus regarding prominent themes was reached. A reflective journal was kept throughout the research process to make note of personal thoughts and opinions, to enhance transparency and maintain a record of research decisions generating an audit trail [19, 20].

A researcher’s experience, beliefs, and worldviews will ultimately influence the way a study is conducted and presented [17]. The primary researcher who conducted the interviews, performed data analysis, and structured this manuscript is an able-bodied female with more than 10 years of SCI research experience. She has performed numerous qualitative studies, but operates from a postpositivist perspective and applies a quantitative lens to qualitative work [17]. A descriptive phenomenological approach was employed to describe the experience of others with lived experience regarding the phenomenon, and personal interpretation by the researcher was avoided [21]. To ensure the results presented stayed close to the data, direct quotations from participant transcripts were used to support statements made by the author.

Results

Participants

Six men between the ages of 24 and 49 who were living in Canada with complete or incomplete SCI (C4-T12) participated in this study. Participants’ time since injury ranged from 7 months to 29 years (mean ~14 years). All of the men identified as being heterosexual.

Unmet need for sexual health information

All of the participants in this study said that the number of resources available and/or provided to them during rehabilitation was inadequate, and that the content of available resources was also inadequate. Generally, the participants explained that sexuality was briefly touched on in rehabilitation, but that it was not a priority, stating there was no real emphasis on the topic and that discussions about sex were “in passing” (Joe). They described a lack of time to discuss sexuality with their healthcare providers, as well as a greater focus on other areas of healthcare in rehabilitation programs. “I think when you’re in a rehabilitation setting, they tend to have a lot of focus on like the importance of physiotherapy, the importance of occupational therapy and why you do that. They try to enlighten you on your bladder issues after your spinal cord injury, your bowel issues, the importance of your skin integrity, pressure sores, and they cover a lot of other really important things. But for some reason a lot of them have these really long check lists, but they always leave off the sexual health aspect after spinal cord injury” (Elliott).

Participants explained that because everyone experiences sexuality differently, it could be difficult to provide relevant information which may contribute to the lack of attention to sexuality in rehabilitation programs. In addition, participants recognized the sensitive nature of the topic and stated sex was not something people wanted to talk about. As a result, it was a difficult conversation for the men to start and they tended to rely on their healthcare providers to initiate the discussion. Unfortunately, this conversation did not always transpire. Joe said: “[in rehabilitation] sex is just briefly mentioned. Like they ask if you have any questions and then it’s done, you never talk about it anymore. There’s no actual emphasis on sex and sexual function. It was very much in passing. You could kind of tell they didn’t really want to talk about it or that they were just checking it off a list. Just like, ‘okay I mentioned sexuality, let’s move on to the next thing.’ It was very brief. I think because their focus is more on the physical rehabilitation and they are trying to get people moved through there.”

In some situations where information was provided, the participants said that resources did more harm than good by making sex after SCI seem unappealing. One example of this was a VHS tape that portrayed a couple pausing mid-sexual act to allow the man with SCI to empty his bladder with the help of his partner before continuing. Elliott relayed his experience: “They gave me a really strange VHS tape and it was bizarre (laughs) and probably did more harm than good. It was a tape, specifically about sex after spinal cord injury. And it was from the 80 s. And it was ridiculous. Like it had a bunch of different couples engaging in a variety of different sexual acts.

Obviously, it exposed me to the reality of it, but at the same time I was like, ‘I don’t like this and I don’t like [it] if that’s what the rest of my life is going to look like with spinal cord injury and sexuality.” Information provided in rehabilitation and resources accessed on their own from the internet were occasionally unreliable and inaccurate compared to what they actually experienced.

Joe shared: “Google provided me with some information, but not all that information is correct.” The reported absence of resources was not a result of the men’s disinterest in sexuality or sexual education post injury. “It was a conversation I was thinking about and the conversation that I wanted to have, but they didn’t really answer a lot of the questions that I was looking for. So okay, yes you can have sex, but that’s where it ended” (Elliott).

Healthcare provider’s knowledge and comfort discussing sexuality

Participants revealed that their healthcare providers were knowledgeable about medications that could assist with sexual activities post injury, including possible complications and interactions, and said that their healthcare providers were somewhat knowledgeable on the physiology and lacked a crucial component for understanding the topic as they did not have any personal knowledge of what it means to experience sexuality after SCI. “It’s hard to say if doctors are knowledgeable about sex after spinal cord injury because not a ton of those conversations have ever taken place. Umm, yes, I mean they’re knowledgeable about sexuality in general, but in how it’s going to work as a function of life after the injury, meh” said Paul. As a result, several participants felt they knew more about the topic than their healthcare providers: “I know from a personal perspective, I probably know more about this [sex after SCI] through all the research that I’ve done than my spinal cord injury doctor does. So, like he knows a certain amount of things, but I don’t think he knows more than I do” Elliott explained.

Participants said that the information they received from healthcare providers about sexuality was too clinical and too technical. According to the men, healthcare providers failed to address aspects of sexuality beyond the traditional assumption of sex as a physical penetrative act, and focused solely on physical components of sexuality that may be more relevant to individuals who are able-bodied. Participants wished to be educated on new ways to approach sexuality that were “outside the box” and that may be better suited to those with SCI. Elliott said: “It’s just like, ‘we’re not going to help you think outside the box and realize you can use other devices, or you don’t just have to get to penetration.’”

In addition, participants explained that healthcare providers were often uncomfortable discussing sexuality, though this was an assumption for some based on the premise that no conversations about sex had ever taken place. Lastly, participants said that their healthcare providers did not understand the importance of talking about, and learning about, sexuality after SCI. “…I think a lot of them [healthcare providers] don’t really understand the importance of it [sex], and maybe they’re not comfortable bringing it up” explained Elliott.

Importance of receiving sexual health information

Participants clarified that it was important to include the topic of sexual health in rehabilitation programs and to achieve satisfaction in their sexual lives as sexuality was linked to their physical health, mental health, and to their overall well-being. They said that by improving their sexual experiences and sexual satisfaction post injury, other health issues, both mental and physical, would also improve which would lead to improvements in their overall QOL. “It’s [sex] not only linked to your physical health. Like this can have a direct impact on your psychological health and your mental health and it could be triggering a lot of other things [physical and mental health issues]. My thoughts about myself, and just life in general is not always the greatest, but they probably would be if my sexuality was a little bit more positive” (Elliott).

Participants revealed that sexuality was not prioritized in rehabilitation; however, receiving information about sexuality and having a fulfilling sexual life post injury were identified as being important. For some, being adequately informed about sexuality-related topics could have resulted in different outcomes for their lives. One participant disclosed that he “wasted” time during what should have been his peak sexual activity years due to a lack of sexual education and believing that he could not have sex as a result of his SCI. This participant believed his life may have been different, and that he could be in a different place than he is now if someone had told him that participating in sexual activities and experiencing a satisfying sexual life were still possible post injury. “I wasted 6–7 years of perfect university time and like experimenting which is what a lot of people do in university. But I skipped over 4 years of my undergrad thinking that a lot of that stuff was not possible. So, I think if somebody told me earlier on that I could still have sex and brought all of this to my attention, I would probably be in a very different position today than I am” (Elliott).

Recommendations for sexual health information

Participants made recommendations for the most appropriate and effective delivery of sexual health education information post injury. Participants said it could be overwhelming to search for this information on their own and suggested that it would be most helpful if there was one designated place they could go to find all relevant information, whether that be a designated sex therapist or a “sexpert,” an online email address they could send their questions to and receive accurate responses, or an information hub containing links to all of the existing sexual health resources. “It’d be cool to see them have someone there that’s actually trained in sexuality.

Someone with actual resources. We need a hub of information” said Joe.

Participants were somewhat open to receiving information from a variety of healthcare providers; however, some did convey that while their doctors may be helpful for explaining the physical aspects of sexuality, they would not be the best person to have this conversation with.

Participants said it was difficult to discuss sexuality with their doctors with whom they had existing relationships for fear of being judged. They said that their doctors held a position of power which made it challenging to be vulnerable with this very personal issue, and said that this exchange seemed too formal. Generally, participants preferred to receive this information from a peer, someone of a similar age and injury who could relate to their lived personal feelings and experiences. “The biggest thing is for the person who’s giving you information to say ‘oh yeah, the first year of my injury I had these feelings, and often people feel this,’ rather than saying, you know, ‘there is this medication and this medication’ with like a much more kind of textbook-type description. Like more of a personal kind of experience is better” Joe shared.

Participants identified open communication in a no judgment zone as being important when discussing sex, and said that sex should be incorporated into rehabilitation programs by covering the topic the same way they cover other health issues such as bladder management or skin integrity. Elliott said: “I think a really easy way to integrate it is to have it as an option. And then okay, you cover bladder one week or bring that up one week, the next week you cover sexuality.

Because it is really not that different when you think about it, since it’s all part of your health care.” Having someone reach out early on after injury and open the door for conversations about sex was identified as being important, and a small gesture that could make a big difference would be to just ‘bring it up’ and get the conversation about sex going. Joe suggested: “I think there should be a person that would reach out early on, like a sex specialist.”

Participants also discussed the optimal timing to receive this information. Majority wished to receive information about sexuality immediately after injury, and then continue to receive it when they are back in the community and ready to use it. Peter shared the following: “I would probably want to know about it as soon as possible. I would like awareness of information.

Whether you actually execute it or not is different, but I would like to know the facts, all that, ahead of time. And then I can learn from it and be better educated when that time comes.” Will had a similar perspective: “Do it sooner rather than later because that’s a problem that we had.

There were no resources that we were given on how to handle this stuff [sexuality]. If I could make one change in how that’s all done, is make sure that that is a topic that’s covered as early as possible.” Conversely, some men wanted to wait at least a year before receiving this information, explaining that for the first year they had other priorities and/or did not feel like a sexual person. Steve said: “Oh I would at least give it a year because you’re so busy trying to You’re trying to do rehab, that sort of stuff.” Considering these two perspectives, information should be made available and offered to men soon after injury which may provide answers to the questions they have early on about sexuality and also inform them that sex is still an option.

Knowing this information is available, the men can choose to access it when they are ready to do so.

Discussion

This study contributed to further understanding the experience of sexuality for men after SCI and revealed that healthcare providers, rehabilitation programs, and available resources are, in general, not meeting the needs of men with SCI. The current literature has reported difficulties integrating the topic of sexual health into rehabilitation programs for those with disabilities [5]. While many healthcare providers do consider sexuality an important issue to approach during rehabilitation, a study of 244 healthcare providers found that only 12% felt sufficiently trained to address the topic [22]. Healthcare providers revealed that sexual health was rarely incorporated in their training curriculum and felt that it was not their professional responsibility to handle [22]. This may account for comments made by the men in the current investigation regarding the availability of sexual health resources and the knowledge and comfort level of their healthcare providers to cover the topic.

Men continue to have concerns about sexuality years after their SCI [23] and agree that continued access to sexual supports after leaving rehabilitation is important, yet there is little consensus regarding the delivery of this information [24]. Healthcare providers working in sexual rehabilitation have identified the need for a standardized and multidisciplinary approach which incorporates expertise from various disciplines to effectively address the complexity of sexual health [5, 25]. Researchers have launched a project to improve standards of SCI rehabilitation in Canada by 2020, including sexual health. The project aims to encourage a liberal environment regarding sexuality after SCI and to pinpoint sexual health needs through identification, development, and implementation of key indicators related to sexual health after SCI [11]. Initiatives such as these are vital for better meeting the needs of this population regarding their sexual health.

The top preference of the participants in this study for receiving information about sexual health was an informal, nontechnical, nonclinical approach from one designated “sexpert.” That being said, open communication in an uncritical environment with someone who is approachable and receptive was important for improving the quality of the interaction between the patient and the healthcare provider. In a study which looked at improving sexual rehabilitation services from the perspective of the patient, McAlonan found that interpersonal skills and character traits of the healthcare provider including an open and friendly personality, and comfort and confidence to both talk and listen during discussions about sexuality were more important than who provided the information and what their role as a healthcare provider was [26].

Participants conveyed that sexual health information would be most beneficial if it took into account the changed body after SCI. They suggested that resources should help them “think outside the box” and suggest new ways to explore and experience sexuality. Resources should consider ways of experiencing intimate connection beyond the traditional view of sexuality which has been focused on erection, penetration and ejaculation [8]. Conventional sexual health information should be provided, but it is important that researchers, clinicians, and healthcare providers are open to expanding their views of sex and sexuality when working with this population by considering and discussing alternate ways in which individuals living with SCI may be able to explore and experience sexuality. Finding a balance between open conversation and respecting the comfort level of both the patient and healthcare provider should be explored. Healthcare providers discussing sexual activities post injury should be aware of their own biases and should be prepared to suspend any judgments to facilitate safe and productive discussions about sex [15].

It is important that researchers and clinicians consider the needs of the individuals they aim to assist by involving them in the development and evaluation of programs and treatments, maximizing the potential for benefits to be experienced. Future work should ensure that from the perspective of the patient, sexual health programs are being developed and delivered in an effective and suitable manner.

Strengths and limitations

This qualitative approach allowed the men’s voices regarding their own sexuality to emerge. The sample reflected a spectrum of heterosexual men’s experiences regarding their sexuality across various ages, time points since injury, injury levels, and injury classifications.

The average time since injury for these participants was ~14 years. It is possible that rehabilitation practices have been updated or improved since some of these men were in rehabilitation programs, though information provided by the most recently injured participant (7 months post injury) was consistent with the others. All of the participants in this study were male and identified as heterosexual. The results from this study may not elucidate the opinions of individuals outside these parameters. The goal of phenomenological work is to uncover the personal lived experiences of individuals who have first-hand knowledge of the topic under investigation and is not meant to be representative of a population [14]. While the small sample size was appropriate for this type of deep and exploratory study, additional research using a larger number of participants may be beneficial for application to a wider population. Data reported here are a subset of information obtained from the interview guide that are relevant to sexual education and sexual rehabilitation post injury. Themes identified from the transcripts in their entirety are intertwined, and the evolving meaning of social constructs related to sexuality for men after SCI should be considered when developing sexual rehabilitation frameworks. Data derived from other sections of the interview guide can be found in [12] and may be reviewed to obtain a deeper understanding of the basis for recommendations made in this paper.

Conclusions

Normalization of the topic of sexuality after SCI is important in facilitating conversations about sex for both patients and healthcare providers [27], and sexual health should be a standard component of rehabilitation that is offered to all patients, not just those who are assertive enough to ask for it [5]. Healthcare providers should be aware of the resources available in their communities [23], and sexual health should be fully integrated into rehabilitation programs and primary care facilities for individuals living with SCI [24]. Participants felt they should have access to a healthcare provider trained in sexuality who would have the skills and resources to address their concerns. Participants also noted that a good first step for moving forward with sexual education post injury would be for healthcare providers to “just bring up” the topic and initiate a conversation about sex.

Information from this study may help to inform the development and delivery of effective sexual education for men after SCI and guide future rehabilitation initiatives to improve QOL and overall life satisfaction for these individuals.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the possibility of identifying information occurring in the in-depth qualitative data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Noonan VK, Fingas M, Farry A, Baxter D, Singh A, Fehlings MG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of spinal cord injury in Canada: a national perspective. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38:219–26.

Jim, et al. Press kit—get the facts. Spinal Cord Injury Ontario. sciontario.org/information-news/news-media/press-kit/.

Sharma SC, Singh R, Dogra R, Gupta SS. Assessment of sexual functions after spinal cord injury in Indian patients. Int J Rehabil Res. 2006;29:17–25.

Siösteen A, Lundqvist C, Blomstrand C, Sullivan L, Sullivan M. Sexual ability, activity, attitudes and satisfaction as part of adjustment in spinal cord-injured subjects. Paraplegia. 1990;28:285–95.

Pieters R, Kedde H, Bender J. Training rehabilitation teams in sexual health care: a description and evaluation of a multidisciplinary intervention. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:732–9.

Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Steins SA, Elliott SL. The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:328–37.

Low WY, Tunku NTTZ. Sexual issues of the disabled: implications for public health education. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2000;12:78–83.

Sunilkumar MM, Boston P, Rajagopal MR. Sexual functioning in men living with a spinal cord injury- a narrative literature review. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:274–81.

Basson PJ, Walter S, Stuart AD. A phenomenological study into the experience of their sexuality by males with spinal cord injury. Health SA Gesondheid. 2003;8:3–11.

Herson L, Hart KA, Gordon MJ, Rintala DH. Identifying and overcoming barriers to providing sexuality information in the clinical setting. Rehabil Nurs. 1999;24:148–51.

Elliott. S, Jeyathevan G, Hocaloski S, O’connell C, Gulasingam S, Mills S, et al. Conception and development of sexual health indicators to advance the quality of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: SCI-High Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42:68–84.

Kathnelson JD, Kurtz Landy CM, Ditor DS, Tamim H, Gage WH. Examining the psychological and emotional experience of sexuality for men after spinal cord injury. Cogent Psychol. 2020;7:1722355 .https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1722355.

Patton MQ, editor. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002.

Polit DF, Hungler BP. Nursing research: principles and methods. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1995.

Smith JA, Osborn M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis. Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to methods. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2008.

Creswell J, editor. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007.

Giorgi A, editor. The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: a modified husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press; 2009.

Liamputtong P, editor. Qualitative research methods. 3rd ed. Victoria: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Carpenter C, Suto M, editors. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: a practical guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2008.

Ortlipp M. Keeping and using reflective journals in the qualitative research process. Qualitative Rep. 2008;13:695–705.

Cohen MZ, Omery A. Schools of phenomenology: implications for research. In: Morse JM, editor. Critical issues in qualitative methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994.

Gianotten WL, Bender JL, Post MW, Höing M. Training in sexology for medical and paramedical professionals: a model for the rehabilitation setting. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2006;21:303–17.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Sexuality and reproductive health in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:281–336.

Aikman K, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, McCuaig F. Sexual health in men with traumatic spinal cord injuries: a review and recommendations for primary health-care providers. Am J Men’s Health. 2018;12:2044–54.

Elliott S, Hocaloski S, Carlson M. A multidisciplinary approach to sexual and fertility rehabilitation: the sexual rehabilitation framework. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017;23:49–56.

McAlonan S. Improving sexual rehabilitation services: the patient’s perspective. Am J Occup Ther. 1996;50:826–34.

Eisenberg NW, Andreski S, Mona LR. Sexuality and physical disability: a disability-affirmative approach to assessment and intervention within health care. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2015;7:19–29.

Acknowledgements

We thank Merna Seliman who assisted with data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JDK was responsible for developing the protocol, collecting and analyzing data, interpreting results and writing the report. JDK has had full access to the data in the study and has final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. CMKL contributed to development of the protocol, interpretation of results and provided feedback on the report. DSD contributed to protocol development and provided feedback on the report. HT contributed to protocol development and provided feedback on the report. WHG was responsible for development of the protocol, interpretation of results and provided.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

This file has been reviewed and received ethics clearance from the York University Research Ethics Board (file number 2019–004) and the Brock University Research Ethics Board (file number 18–235). We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kathnelson, J.D., Kurtz Landy, C.M., Ditor, D.S. et al. Supporting sexual adjustment from the perspective of men living with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 58, 1176–1182 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0479-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0479-6

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

“It’s Not, Can You Do This? It’s… How Do You Feel About Doing This?” A Critical Discourse Analysis of Sexuality Support After Spinal Cord Injury

Sexuality and Disability (2024)

-

Primary Care in the Spinal Cord Injury Population: Things to Consider in the Ongoing Discussion

Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports (2023)

-

The contribution of bio-psycho-social dimensions on sexual satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury and their partners: an explorative study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2022)

-

Sexuality Support After Spinal Cord Injury: What is Provided in Australian Practice Settings?

Sexuality and Disability (2022)

-

Utilizing the Delphi Method to Assess Issues of Sexuality for Men Living with Spinal Cord Injury

Sexuality and Disability (2021)