Abstract

Background

We assessed (a) the effects of postpartum depression (PPD) trajectories until 6 months postpartum on infants’ socioemotional development (SED) at age 12 months, and (b) the mediating role of maternal self-efficacy (MSE), and the additional effect of postpartum anxiety at age 12 months.

Methods

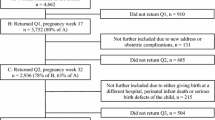

We used data from POST-UP trial (n = 1843). PPD was assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 1, 3, and 6 months. Infants’ SED was assessed at 12 months using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire-Social-Emotional (ASQ-SE). Structural equations were applied to estimate the effect of PPD trajectories on infants’ SED and mediation by MSE. The additional effects of postpartum anxiety were assessed with conditional regression.

Results

Higher levels of PPD over time were associated with a lower SED (coefficient for log-EPDS 3.5, 95% confidence interval 2.8; 4.2, e.g., an increase in the EPDS score from 9 to 13 worsens the ASQ-SE by 1.3 points). About half of this relationship was mediated by MSE. Postpartum anxiety had an independent adverse effect on SED.

Conclusions

PPD and postpartum anxiety have a negative impact on infants’ SED. MSE as a mediator may be a potential target for preventive interventions to alleviate the negative effects of maternal psychopathology on infants’ SED.

Impact

-

The trajectories of postpartum depression (PPD) from 1 month to 6 months were negatively related to infants’ socioemotional development (SED) at age 12 months, underlining the importance of repeated assessment of PPD.

-

Maternal self-efficacy (MSE) mediated the association between PPD and SED, implying MSE could be a potential target for preventive interventions.

-

An additional independent negative effect of postpartum anxiety was identified, implying the assessment of postpartum anxiety also has a surplus value to identify mothers at risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data for the current study is not publicly available. Reasonable requests for data can be made to the principal investigator of the Post-Up trial, Dr. Magda M. Boere-Boonekamp; m.m.boere-boonekamp@utwente.nl.

References

Aktar, E. et al. Fetal and infant outcomes in the offspring of parents with perinatal mental disorders: earliest influences. Front. Psychiatry 10, 391 (2019).

Stewart, D. E. & Vigod, S. N. Postpartum depression: pathophysiology, treatment, and emerging therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 70, 183–196 (2019).

Pearlstein, T., Howard, M., Salisbury, A. & Zlotnick, C. Postpartum depression. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200, 357–364 (2009).

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J. Y. & Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health 15, 1745506519844044 (2019).

Moehler, E. et al. Childhood behavioral inhibition and maternal symptoms of depression. Psychopathology 40, 446–452 (2007).

Feldman, R. et al. Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 48, 919–927 (2009).

Carter, A. S., Garrity-Rokous, F. E., Chazan-Cohen, R., Little, C. & Briggs-Gowan, M. J. Maternal depression and comorbidity: predicting early parenting, attachment security, and toddler social-emotional problems and competencies. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 18–26 (2001).

Thompson, R. A. & Virmani, E. A. Socioemotional development. in Encyclopedia of Human Behavior 2nd edn, 504–511 (Elsevier Inc., 2012).

Vertsberger, D. & Knafo-Noam, A. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and longitudinal associations with children’s observed distress to limitations: From pregnancy to toddlerhood. Dev. Psychol. 55, 123–134 (2019).

Edwards, D. M., Gibbons, K. & Gray, P. H. Relationship quality for mothers of very preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 92, 13–18 (2016).

Sarfi, M., Smith, L., Waal, H. & Sundet, J. M. Risks and realities: dyadic interaction between 6-month-old infants and their mothers in opioid maintenance treatment. Infant Behav. Dev. 34, 578–589 (2011).

Paulson, J. F., Dauber, S. & Leiferman, J. A. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics 118, 659–668 (2006).

Bosquet Enlow, M. et al. Differential effects of stress exposures, caregiving quality, and temperament in early life on working memory versus inhibitory control in preschool-aged children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 44, 339–356 (2019).

Vaiserman, A. M. Epigenetic programming by early-life stress: evidence from human populations. Dev. Dyn. 244, 254–265 (2015).

O’Donnell, K. J. & Meaney, M. J. Epigenetics, development, and psychopathology. Annu Rev. Clin. Psychol. 16, 327–350 (2020).

Van Der Waerden, J. et al. Maternal depression trajectories and children’s behavior at age 5 years. J. Pediatr. 166, 1440–1448.e1 (2015).

Kettunen, P., Koistinen, E. & Hintikka, J. Is postpartum depression a homogenous disorder: time of onset, severity, symptoms and hopelessness in relation to the course of depression. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 1–9 (2014).

Vliegen, N., Casalin, S. & Luyten, P. The course of postpartum depression: a review of longitudinal studies. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 22, 1–22 (2014).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147 (1982).

Coleman, P. K. & Karraker, K. H. Maternal self-efficacy beliefs, competence in parenting, and toddlers’ behavior and developmental status. Infant Ment. Health J. 24, 126–148 (2003).

Jones, T. L. & Prinz, R. J. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 25, 341–363 (2005).

Wernand, J. J., Kunseler, F. C., Oosterman, M., Beekman, A. T. F. & Schuengel, C. Prenatal changes in parenting self-efficacy: linkages with anxiety and depressive symptoms in primiparous women. Infant Ment. Health J. 35, 42–50 (2014).

Bates, R. A. et al. Relations of maternal depression and parenting self-efficacy to the self-regulation of infants in low-income homes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 2330–2341 (2020).

Rees, S., Channon, S. & Waters, C. S. The impact of maternal prenatal and postnatal anxiety on children’s emotional problems: a systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 28, 257–280 (2019).

Aktar, E. & Bögels, S. M. Exposure to parents’ negative emotions as a developmental pathway to the family aggregation of depression and anxiety in the first year of life. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 20, 369–390 (2017).

Murray, L., Creswell, C. & Cooper, P. J. The development of anxiety disorders in childhood: an integrative review. Psychol. Med. 39, 1413–1423 (2009).

van der Zee-Van Den Berg, A. I. et al. Post-up study: postpartum depression screening in well-child care and maternal outcomes. Pediatrics 140, e20170110 (2017).

van der Zee-Van den Berg, A. I., Boere-Boonekamp, M. M., Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C. G. M. & Reijneveld, S. A. The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale: Stable structure but subscale of limited value to detect anxiety. PloS One 14, e0221894 (2019).

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 150, 782–786 (1987).

Squires, J., et al. Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Social-Emotional: A Parent-Completed, Child-Monitoring System for Social-Emotional Behaviors (Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company, 2002).

McCrae, J. S. & Brown, S. M. Systematic review of social–emotional screening instruments for young children in child welfare. Res. Soc. Work Pr. 28, 767–788 (2018).

De Wolff, M. S., Theunissen, M. H. C., Vogels, A. G. C. & Reijneveld, S. A. Three questionnaires to detect psychosocial problems in toddlers: a comparison of the BITSEA, ASQ:SE, and KIPPPI. Acad. Pediatr. 13, 587–592 (2013).

Pop, V. J., Komproe, I. H. & van Son, M. J. Characteristics of the Edinburgh post-natal depression scale in The Netherlands. J. Affect Disord. 26, 105–110 (1992).

Matthey, S., Henshaw, C., Elliott, S. & Barnett, B. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – Implications for clinical and research practice. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 9, 309–315 (2006).

Pedersen, F. A., Bryan, Y., Huffman, L. & Del Carmen, R. Constructions of self and offspring in the pregnancy and early infancy periods. In the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development (1989).

Porter, C. L. & Hsu, H. C. First-time mothers’ perceptions of efficacy during the transition to motherhood: Links to infant temperament. J. Fam. Psychol. 17, 54–64 (2003).

Marteau, T. M. & Bekker, H. The development of a six‐item short‐form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 31, 301–306 (1992).

Tendais, I., Costa, R., Conde, A. & Figueiredo, B. Screening for depression and anxiety disorders from pregnancy to postpartum with the EPDS and STAI. Span. J. Psychol. 17, e7 (2014).

Gunning, M. D. et al. Assessing maternal anxiety in pregnancy with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): issues of validity, location and participation. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 28, 266–273 (2010).

van der Bij, A. K., de Weerd, S., Cikot, R. J. L. M., Steegers, E. A. P. & Braspenning, J. C. C. Validation of the Dutch short form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Considerations for usage in screening outcomes. Community Genet 6, 84–87 (2003).

Grote, N. K. et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 1012–1024 (2010).

White, I. R., Royston, P. & Wood, A. M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat. Med. 30, 377–399 (2011).

Kempen, G. I. J. M. & Van Eijk, L. M. The psychometric properties of the SSL12-I, a short scale for measuring social support in the elderly. Soc. Indic. Res. 35, 303–312 (1995).

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M. & Keller, S. D. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 34, 220–233 (1996).

Landgraf, J. M., Vogel, I., Oostenbrink, R., van Baar, M. E. & Raat, H. Parent-reported health outcomes in infants/toddlers: Measurement properties and clinical validity of the ITQOL-SF47. Qual. Life Res. 22, 635–646 (2013).

Morris, T. P., White, I. R. & Royston, P. Tuning multiple imputation by predictive mean matching and local residual draws. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 1–13 (2014).

Gupta, P. L., Gupta, R. C. & Ong, S. H. Modelling count data by random effect poisson model. Sankhya Indian J. Stat. 66, 548–565 (2003).

de Kroon, M. L. A., Renders, C. M., van Wouwe, J. P., van Buuren, S. & Hirasing, R. A. The Terneuzen Birth Cohort: BMI change between 2 and 6 years is most predictive of adult cardiometabolic risk. PloS One 5, e13966 (2010).

van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide. (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR Online 8, 23–74 (2003).

Porter, E., Lewis, A. J., Watson, S. J. & Galbally, M. Perinatal maternal mental health and infant socio-emotional development: a growth curve analysis using the MPEWS cohort. Infant Behav. Dev. 57, 101336 (2019).

Atkins, R. Self-efficacy and the promotion of health for depressed single mothers. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 7, 155–168 (2010).

Kunseler, F. C., Willemen, A. M., Oosterman, M. & Schuengel, C. Changes in parenting self-efficacy and mood symptoms in the transition to parenthood: a bidirectional association. Parenting 14, 215–234 (2014).

Leerkes, E. M. & Crockenberg, S. C. The development of maternal self-efficacy and its impact on maternal behavior. Infancy 3, 227–247 (2002).

Prenoveau, J. M. et al. Maternal postnatal depression and anxiety and their association with child emotional negativity and behavior problems at two years. Dev. Psychol. 53, 50–62 (2017).

Squires, J., Bricker, D., Heo, K. & Twombly, E. Identification of social-emotional problems in young children using a parent-completed screening measure. Early Child Res. Q 16, 405–419 (2001).

Schwab-Reese, L. M., Schafer, E. J. & Ashida, S. Associations of social support and stress with postpartum maternal mental health symptoms: Main effects, moderation, and mediation. Women Health 57, 723–740 (2017).

Kvalevaag, A. L. et al. Paternal mental health and socioemotional and behavioral development in their children. Pediatrics 131, e463–e469 (2013).

Jawahar, M. C., Murgatroyd, C., Harrison, E. L. & Baune, B. T. Epigenetic alterations following early postnatal stress: a review on novel aetiological mechanisms of common psychiatric disorders. Clin. Epigenetics 7, 1–13 (2015).

Funding

Funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (grant number 80-82470-98-012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.K.S. drafted the initial manuscript, carried out the data analyses and revised the manuscript. M.L.A.d.K. conceptualized and supervised the study, supervised the data analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript. S.A.R. and C.A.H. supervised the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript. J.A. carried out and supervised data analyses, and revised the manuscript. A.I.v.d.Z.-v.d.B. and M.M.B.-B. conceptualized and designed the POST-UP trial, and coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Subbiah, G.K., Reijneveld, S.A., Hartman, C.A. et al. Impact of trajectories of maternal postpartum depression on infants’ socioemotional development. Pediatr Res (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02697-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02697-w

- Springer Nature America, Inc.