Abstract

Genetics research has potential to alleviate the burden of mental disorders in low- and middle-income-countries through identification of new mechanistic pathways which can lead to efficacious drugs or new drug targets. However, there is currently limited genetics data from Africa. The Uganda Genome Resource provides opportunity for psychiatric genetics research among underrepresented people from Africa. We aimed at determining the prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder (MDD), suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol abuse, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and probable attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among participants of the Uganda Genome Resource. Standardised tools assessed for each mental disorder. Prevalence of each disorder was calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate logistic regression models evaluated the association between each mental disorder and associated demographic and clinical factors. Among 985 participants, prevalence of the disorders were: current MDD 19.3%, life-time MDD 23.3%, suicidality 10.6%, PTSD 3.1%, alcohol abuse 5.7%, GAD 12.9% and probable ADHD 9.2%. This is the first study to determine the prevalence of probable ADHD among adult Ugandans from a general population. We found significant association between sex and alcohol abuse (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.26 [0.14,0.45], p < 0.001) and GAD (AOR = 1.78 [1.09,2.49], p = 0.019) respectively. We also found significant association between body mass index and suicidality (AOR = 0.85 [0.73,0.99], p = 0.041), alcohol abuse (AOR = 0.86 [0.78,0.94], p = 0.003) and GAD (AOR = 0.93 [0.87,0.98], p = 0.008) respectively. We also found a significant association between high blood pressure and life-time MDD (AOR = 2.87 [1.08,7.66], p = 0.035) and probable ADHD (AOR = 1.99 [1.00,3.97], p = 0.050) respectively. We also found a statistically significant association between tobacco smoking and alcohol abuse (AOR = 3.2 [1.56,6.67], p = 0.002). We also found ever been married to be a risk factor for probable ADHD (AOR = 2.12 [0.88,5.14], p = 0.049). The Uganda Genome Resource presents opportunity for psychiatric genetics research among underrepresented people from Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental disorders have persisted among the top ten leading causes of disease burden worldwide, with no evidence of global reduction in the burden since 1990 [1]. It is estimated that 1 in every 8 people in the world lives with a mental disorder [2]. Mental disorders account for 4.9% of the global disability-adjusted life-years and 14.6% of the global years lived with disability [1]. Some of the common mental disorders include major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), suicidality and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The global age-standardised prevalence of any mental disorder has been estimated at 12.3% [1] while the individual global prevalence for anxiety disorders, depressive disorders and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been estimated at 3.8%, 3.4% and 1.1% respectively, accounting for point, 12 month and lifetime prevalence using pooled prevalence ratios [1].

Over 80% of the burden of mental disorders pertains to low- and middle-income-countries (LMIC) [3] where the treatment gap for psychiatric disorders approaches 90% [4]. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) an age-standardised prevalence of 13.4% has been estimated for any mental disorder [1] while prevalence of 4.5%, 3.5% and 0.6% has been reported for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and ADHD respectively. The age-standardised prevalence of depressive disorders is higher in SSA than any other region globally [1].

In Uganda, the prevalence of any mental disorder has been estimated at 24.2% (95% C.I 19.8%–28.6%) among adults [5]. For depression, a pooled prevalence of 30.2% has been determined by a systematic review and a meta-analysis among heterogeneous samples [6] while prevalence estimates of 4.2–29.3% have been determined among general populations from various study sites in Uganda [7,8,9,10,11]. For anxiety disorders, a prevalence of 22.2% has been reported among adults in Uganda [5]. Combined together, depression and anxiety disorders have been reported to affect approximately one in four persons in Uganda [5].

Mental disorders are a huge public health problem with marked consequences for society. They lead to severe distress and functional impairment in several domains including social and work environments [12] and those which set on early in life have been strongly associated with truncated education attainment [13]. There is currently no cure for most mental illnesses. However, there are evidenced psychological and pharmacological treatments which have been found to effectively minimize the symptoms so as to allow the individual to function in work, school, or social environments. These are described for the various mental disorders below;

Major depressive disorder

Can be managed with various treatment modalities, including pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, interventional, and lifestyle modification [14]. Initial treatment of MDD involves medications and/or psychotherapy, with combination therapy proving more effective than either alone [15, 16]. Antidepressants, classified as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), serotonin modulators, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and atypical antidepressants are commonly used [14]. SSRIs, such as fluoxetine and sertraline, are first-line choices, and they acting by increasing serotonin activity [17]. SNRIs, like venlafaxine, target non-responders or those with comorbid pain disorders. Other classes include serotonin modulators, TCAs, MAOIs, and atypical antidepressants like bupropion, agomelatine, and mirtazapine, each with distinct mechanisms [18,19,20].

For psychotherapeutic treatment, this is normally considered for mild to moderate MDD. It emphasizes cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT), supplemented by supportive therapy and psychoeducation [21]. Additional treatments comprise electroconvulsive therapy, proven highly efficacious for severe MDD [22], and physical exercise [23].

Suicidality

The most widely used psychotherapeutic interventions for suicidality are dialectical behavioural therapy and CBT while other innovative interventions like group therapies and internet-based therapies have been tried but these require further study [24]. For pharmacotherapy, a strong evidence of both lithium and ketamine in reducing the risk of suicide has been documented [25].

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Trauma focused psychotherapies are currently the gold standard in treatment of trauma-associated symptoms of PTSD and they include cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure therapy and eye movement, desensitization and restructuring therapy [26]. For pharmacotherapy, SSRIs and SNRIs such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and venlafaxine have been reported to reduce PTSD symptoms when administered at appropriate doses [26].

Alcohol abuse

In pharmacotherapeutic management, naltrexone is the first-line treatment option for alcohol abuse owing to its preferable dosing schedule and ability for treatment to be initiated while the individual is still drinking [27]. Acamprosate has been described as an alternative to naltrexone in patients with contraindications to naltrexone [27]. For patients who are contraindicated or those who do not respond to these two, the next choices are disulfiram or topiramate [27]. Psychotherapeutic treatments for alcohol abuse include motivational enhancement therapy and the twelve-step programs [28, 29]. However, a combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy has been reported to be more efficacious in treating alcohol abuse as compared with usual care and pharmacotherapy [30].

Generalized anxiety disorder

CBT is the psychotherapeutic treatment with the highest evidence for treatment of GAD [31]. However internet therapies have also been proposed where CBT may not be easily available [31]. Pharmacotherapeutic treatment involves using SSRIs (such as escitalopram, paroxetine and sertraline) and SNRIs (such as doluxetine and venlafaxine) as first-line drugs for GAD [31]. Other evidenced drugs in the treatment of GAD include buspirone and benzodiazepines [31].

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

ADHD management involves medical and psychological approaches. Medical options include stimulants (e.g., amphetamines, methylphenidates) or non-stimulants (e.g.,TCAs, non-tricyclic antidepressants, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, alpha-2 noradrenergic agonists). Stimulants work by enhancing neurotransmission but their misuse is a concern [32]. Psychological treatments like CBT, mindfulness, dialectical behavior therapy, and neurofeedback complement medications, though reported less effective in symptom alleviation. They prove useful in addressing residual problems post-medication use [32,33,34,35,36,37].

Mental disorders are complex disorders which arise from complex systems which include several factors such as psychological, genetic, biological, socioeconomic and environmental factors [38]. Mental disorders are heritable and heritability estimates based on sibling data have been reported to vary from 30% for MDD to 80% for ADHD [39]. Genetics studies have potential to identify new mechanistic pathways for mental disorders, which can, in turn lead to new drugs or drug targets for several mental disorders. Recent genome-wide association studies have provided insights into the genetic architecture of several mental disorders like MDD [40], suicidality [41], PTSD [42], schizophrenia [43], alcohol abuse [44], GAD [45] and ADHD [46].

Despite the genetic nature of several mental disorders being illuminated, there is limited genetics data from Africa. There is an urgent need to include people on the Africa continent (continental Africans) in global psychiatric genetics research if they (continental Africans) are to benefit from recent psychiatric genetics discoveries. The Uganda Genome Resource [47] provides an opportunity for psychiatric genetics research among people from Uganda. Briefly, the Uganda Genome Resource comprises genotype data on ∼5000 and whole-genome sequence data on ∼2000 Ugandan individuals from 10 ethno-linguistic groups who are attending an open general population cohort (GPC) in south-western Uganda [47, 48]. This cohort has contributed to several scientific discoveries in Uganda and worldwide [47] and is run by the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit and the current study determined the prevalence and correlates of several mental disorders among participants who are attending the cohort and are also part of the Uganda Genome Resource.

Methods

Study design

This study was undertaken within the GPC of MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit. The GPC is an active cohort of approximately 22,000 participants within 25 villages drawn from a sub-county in Kalungu district in Uganda (https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres-projects-groups/general-population-cohort). A total of approximately 1066 GPC participants whose genetics data is available was assessed for current and life-time diagnoses of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, suicidality and alcohol and substance abuse.

Clinical investigations

A questionnaire was administered by trained psychiatric nurses onto a random sample of consenting GPC participants. The questionnaire contained modules for MDD, suicidality, PTSD, alcohol abuse and GAD from the diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders edition 4 (DSM-IV) - referenced Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) version 5.0.0 [49]. We had previously translated these modules into Luganda (the language spoken by most of the study participants) [50]. The questionnaire also contained a module for the adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder self-report scale (version v1.1) symptoms checklist (https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/adhd/18Q_ASRS_English.pdf). We translated this checklist into Luganda and then used it to assess for traits of ADHD among the study participants.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in compliance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Ethical and scientific clearance for this study was obtained from the science and ethics committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute Science and Ethics Committee in August 2022 (Ref# GC/127/916), the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (Ref# SS1404ES) and the Observational / Interventions Research Ethics Committee of London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (Ref# 28167). Eligible GPC participants (GPC participants whose genetics data is available) were approached and informed about the study by psychiatric research nurses. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants. Consented participants were assessed for mental illnesses, ADHD and alcohol and substance abuse by psychiatric research nurses. Participants who were found to have serious mental illnesses were referred to the mental health clinic at the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit facility at Kyamuliibwa. As per the GPC protocol, each participant was given a bar of soap as compensation for their time.

Data management

STATA version 17.0 was used for all statistical analyses. Frequencies of socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, education level, marital status, body mass index) were described using frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables and median (inter-quartile range) for the continuous variables. The prevalence of dichotomised outcome variables (Current MDD, Lifetime MDD, Suicidality, PTSD, Alcohol abuse, GAD and ADHD) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Proportions of individuals with more than one mental disorder were estimated. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess for inter-item correlation coefficients between the outcome variables. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the relationships between each of the outcome variables and their associated factors adjusting for age and sex as apriori confounders. The likelihood ratio approach was used to determine the best fit for the final model. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Plausible interactions of socio-demographic factors in the logistic regression models were also investigated across all the investigated mental disorders using a likelihood ratio test.

Results

The genetic structure of participants of the Uganda Genome Resource has been published elsewhere [51].

The socio-demographic characteristics and clinical variables of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of mental disorders

Life-time MDD was the most prevalent mental disorder (23.3%, 95% CI = 20.7, 25.9) while PTSD was the least prevalent mental disorder (3.1%, 95% CI = 1.8, 5.4). The prevalence of all the mental disorders assessed for are shown in Table 2.

Correlations among the different mental disorders and alcohol abuse

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between Life-time and current MDD (r = 0.8883, p < 0.05). There was also a statistically significant positive correlation between suicidality and current MDD (r = 0.3532, p < 0.05) and life-time MDD (r = 0.3247, p < 0.05). There was a statistically positive correlations between GAD and current MDD (r = 0.2561, p < 0.05), life-time MDD (r = 0.2311, p < 0.05), suicidality (r = 0.2868, p < 0.05) and PTSD (r = 0.1289, p < 0.05). Table 3 shows the correlation matrix for all the mental disorders and alcohol abuse.

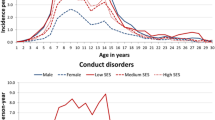

Comorbidity among different mental disorders investigated

High comorbidity of mental disorders was observed and these are shown in the upset plot shown in Fig. 1 below. A total of 155 participants did not present with any of the investigated mental disorders, 39 participants had lifetime MDD, 63 participants had both current and lifetime MDD. A total of 23 participants had both current MDD and lifetime MDD alongside with GAD. The comorbidity extends to another 23 participants who in addition to MDD and suicidality had ADHD. A total of 56 participants had both current and lifetime MDD, suicidality, GAD as well as alcohol abuse and probable ADHD. A total of 12 participants had current and lifetime MDD, suicidality, PTSD, GAD and probable ADHD.

Factors associated with the different mental disorders

There was a statistically significant association between sex and alcohol abuse (AOR = 0.26 [0.14, 0.45], p < 0.001) and GAD (AOR = 1.78 [1.09, 2.49], p = 0.019). Being female was a risk factor associated with GAD while protective against alcohol abuse. BMI was also statistically associated with suicidality (AOR = 0.85 [0.73, 0.99], p = 0.041), alcohol abuse (AOR = 0.86 [0.78, 0.94], p = 0.003) and GAD (AOR = 0.93 [0.87, 0.98], p = 0.008). Per unit increase in BMI was protective against suicidality, alcohol abuse and GAD. There was also a statistically significant association between high blood pressure and life-time MDD (AOR = 2.87 [1.08, 7.66], p = 0.035) and probable ADHD (AOR = 1.99 [1.00, 3.97], p = 0.050). High blood pressure was a risk factor for both life-time MDD and probable ADHD. There was also a statistically significant association between tobacco smoking and alcohol abuse (AOR = 3.2 [1.56, 6.67], p = 0.002). Ever been married was also a risk factor for probable ADHD (AOR = 2.12, [0.88, 5.14], p = 0.049). These results are summarised in Table 4.

There was no statistically significant association between any of the investigated factors and PTSD and current MDD (please see supplementary material, Table S1). Also, there were nonsignificant interactions among the examined socio-demographic factors across all the investigated mental disorders (please see supplementary material, Table S2) and thus we did not report adjusted effect sizes after any interaction.

Discussions

In this study, we determined the prevalence and correlates of MDD, suicidality, GAD, PTSD, probable ADHD and alcohol abuse among participants of the GPC of MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda research Unit, who contributed genetics data to the Uganda Genome Resource.

We have observed prevalence of 19.3 and 23.3% for current and life-time MDD respectively. This prevalence is more than the global prevalence of 3.4% which has been reported for depressive disorders [1]. This prevalence is also more than the prevalence of 4.5% which has been reported in SSA for depressive disorders [1]. However, this prevalence is within the prevalence estimates of 4.2 – 29.3% which have been reported among general populations from various study sites in Uganda [7,8,9,10,11]. Higher rates of MDD in Uganda could be due to poverty, ecological factors and social deprivation (no formal education, unemployment, broken family, low socioeconomic status, food insecurity) [7,8,9, 11].

The observed prevalence of 3.1% for PTSD is less than the prevalence of 11.8% which has been reported among a post-war area in three districts of Northern Uganda [52]. The observed lower prevalence could be due to the fact that this community has not experienced any war or major natural traumatic event since the Ugandan civil war which ended in 1986. It is also worthy of note that the observed prevalence is also comparable to a cross-national lifetime prevalence of 3.9% which was reported by the World mental health survey [53].

The observed prevalence of 10.6% for suicidality is within range of the 1–55% and 0.6–14% prevalence for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide respectively which were observed by a systematic review and meta-analysis among a general population in Ethiopia [54]. This prevalence is also comparable to a prevalence of 12.1% which was reported among randomly selected individuals from three districts of Uganda [55].

The observed prevalence of 5.7% for alcohol abuse is less than the average population lifetime prevalence of 10.7% which was reported by the World mental health survey [56] and the prevalence of 9.8% which was reported among adult populations in Uganda [57].

The observed prevalence of 12.9% for GAD is slightly higher the lifetime prevalence of 9% which has been reported for the United States [58] and the 9.1% prevalence which has been observed among people living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [59]. However, a prevalence as high as 33.2% has been reported among HIV patients in a tertiary institution in Nigeria [60].

We have observed a prevalence of 9.2% for probable ADHD. This prevalence is more than the global prevalence of 1.1% which has been reported for ADHD [1]. This prevalence is also more than the prevalence of 0.6% which has been reported in SSA [1]. The big discrepancy between the observed prevalence and that reported by previous studies could be due to the fact that the assessment tool used by this study assesses for ADHD symptoms without considering functional impairment, thus we report the disorder as probable ADHD. It is however worthy of note that no study has previously determined the prevalence of ADHD among adult Ugandans from a general population. It is also worthy of note that the observed prevalence is comparable to a prevalence of 11% which has been reported among Ugandan children attending paediatric neurology and psychiatry clinics at Mulago Hospital [61] and is less than the prevalence of 40.9% which has been reported among adult Ugandans with substance use disorder attending the Butabika Hospital [62].

Sex was significantly associated with both alcohol abuse and GAD. Female sex was protective against alcohol abuse, a finding which is consistent with findings from previous studies in Uganda and the rest of the world, where alcohol use was reported to be higher among men than women [57, 63, 64]. Being female was however associated with increased odds of GAD. This finding is in line with previous studies which have reported women to be 2- to 3- times more likely to meet a lifetime criterion for GAD as compared with men [65,66,67]. Increased risk for GAD among females could be due to fluctuations in levels of progesterone and oestrogen across the lifespan [68].

Body mass index was associated with suicidality, alcohol abuse and GAD. A unit increase in BMI was protective against suicidality. This finding is consistent with findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis which has reported obesity and overweight to be protective against attempted suicide and suicide mortality [69]. However, definition of suicidality and sex need to be accounted for when interpreting associations between BMI and suicidality. For example, a positive association between obesity and overweight with suicidal ideation has been reported [69] and BMI has been reported to be protective against suicidality among men and paradoxically a risk factor for suicidality among women [70]. A unit increase in BMI was also protective against alcohol abuse. This finding is also consistent with results from a longitudinal study which reported that across adolescence, obesity was protective against alcohol-related problems during early adulthood [71]. This finding supports the food-alcohol competition hypothesis that a tendency to consume processed or sweet high-fat foods compete with a tendency to drink alcohol [72]. A unit increase in BMI was also protective against GAD. This finding is also in agreement with findings from a previous study which reported a negative correlation between BMI and GAD among university students in Bahrain [73]. However this finding contradicts findings from other studies which have reported BMI as a risk factor for GAD [74, 75] and more studies will be required to elucidate this.

High blood pressure was significantly associated with life-time MDD and ADHD. High blood pressure was associated with increased odds of life-time MDD. This finding is in line with a large systematic review and meta-analysis which reported MDD to be a risk factor high blood pressure [76]. This association has been demonstrated to be bidirectional by a large prospective study among young and middle-aged adults [77]. Depressive symptoms were found to be associated with incident hypertension and higher blood pressure levels to be associated with a decreased risk for developing depressive symptoms [76, 77]. Mechanisms that underlie the association between high blood pressure and MDD are yet to be elucidated. High blood pressure was also a risk factor for ADHD. This finding is also in line with findings from a large prospective Swedish cohort study which reported ADHD to be associated with high risk for developing hypertension [78]. It has been proposed that ADHD-associated deficits in delayed discounting and reinforcement sensitivity could impair the future-oriented activities needed to promote good health and thus lead to the development of metabolic disorders like hypertension and type-2 diabetes mellitus [78,79,80].

Smoking tobacco was a risk factor for alcohol abuse. This is consistent with findings from a previous multi-site study which has reported a high correlation between alcohol consumption and tobacco use in Uganda [81] and sub-Saharan Africa in general [82].

Ever been married was significantly associated with ADHD. Individuals who had ever been married had higher odds of being a case of ADHD. This finding could be due to the fact that ADHD often leads to termination of marriages when it is not recognised and treated properly [83, 84].

Past MDD is a predictor of current (recurrent MDD), thus the significant positive correlation observed between current and past MDD. This is due to the high relapse rates which have been reported in MDD [85]. The high relapse rates could be due to variability in response to treatments. A recent meta-analysis of 87 randomized clinical trials (N = 17,540) has indeed reported 14% more variability in response to antidepressants as compared to placebo [86]. Differences among patients or biological heterogeneity within MDD have been proposed as mechanisms which could explain this variability [86, 87]. The significant positive association between suicidality and MDD is due to the high prevalence of suicidality which has been reported in MDD [88]. The significant positive association between GAD and MDD, suicidality and PTSD respectively is also due to the high prevalence of GAD in these disorders. For example, prevalence of GAD as high as 71.7% in MDD [89], 51.9% in suicidality [90] and 27.6% in PTSD [91] have been reported.

Mental disorders investigated exhibited a high degree of comorbidity. The high comorbidity among mental disorders has been attributed in part due to a high level of common genetic risk factors as well as environmental risk modifiers which are shared across several mental disorders [92].

Since common mental disorders are quite prevalent in the Uganda genome resource, there is opportunity to collect the phenotype data and link it with the existing genetics data to conduct genome-wide association studies for several mental disorders. The Uganda genome resource is also poised to grow in sample size and will include proteomics, metabolomics, and single-cell genomic studies which can advance functional genomics research for mental conditions in Uganda and Africa at large. Also, given the longitudinal design of the GPC, there is opportunity to track changes and understand the dynamics of mental disorders and their genetic underpinnings and can ultimately provide insights into causality and progression of mental disorders.

Limitations

We could not elucidate the causation of mental disorders due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. Also, in data collection, we relied on the respondents’ memory and recall bias which may potentially result in a systematic bias against the recall of temporally distant events. Also, given that this was a volunteer-based population study, we may not have captured the most severely affected individuals and there is a likelihood of underrepresentation of the most disadvantaged people in the community studied. Also, while our sample of 985 participants allowed for preliminary insights into the prevalence and correlates of common mental disorders among participants of the Uganda genome resource, we recognize the need for a larger cohort to enhance statistical power and robustness of our findings, most particularly for disorders with a lower prevalence such as PTSD. Despite this limitation, this study makes a great contribution given the dearth of similar studies in Africa. However, we are already undertaking a study in the GPC which seeks to gather phenotype data and biological samples on various mental health conditions among participants of the Uganda genome resource who are still alive and present in the GPC (n = 4000) and additional data from 6,000 GPC participants. Collectively, this effort will encompass 10,000 participants; all of these will have their DNA sequenced using the blended genome-exome technology at the Broad Institute in the United States.

Conclusions

Common mental disorders are quite prevalent among people who comprise the Uganda Genome Resource with current MDD being the most prevalent disorder and PTSD being the least prevalent disorder.

As participants of the Uganda Genome Resource were drawn from an open general population cohort and can still be traced, there is opportunity for psychiatric genetics research where participants can be traced, assessed for mental disorders and the mental disorders data can then be linked with the existing genetics data to allow performance of psychiatric genetics studies. There is currently no representation of people from Africa in global psychiatric genetics databases and performing genetics studies in this cohort will contribute to efforts towards addressing the underrepresentation of people from Africa in global psychiatric genetics databases while provide insights into the genetic nature of mental disorders in Africa.

Data availability

The epidemiological data for this study is available upon request from the principal investigator, following the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit’s data sharing policy which can be found at: https://apps.mrcuganda.org/mrcdatavisibility/Home/. For the genetics data, the array and low- and high-depth sequence data were deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/, accession numbers EGAS00001001558/EGAD00010000965, EGAS00001000545/EGAD00001001639, and EGAS00001000545/EGAD00001005346, respectively. Requests for access to the genetics data may be directed to UGR@mrcuganda.org.

References

GBD Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50.

World Health Organization. Mental disorders Key facts 2022 [cited 2023 23 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders.

Rathod S, Pinninti N, Irfan M, Gorczynski P, Rathod P, Gega L, et al. Mental health service provision in low-and middle-income countries. Health Serv insights. 2017;10:1178632917694350.

Patel V, Maj M, Flisher AJ, De Silva MJ, Koschorke M, Prince M, et al. Reducing the treatment gap for mental disorders: a WPA survey. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:169–76.

Opio JN, Munn Z, Aromataris E. Prevalence of mental disorders in Uganda: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2022;93:199–226.

Kaggwa MM, Najjuka SM, Bongomin F, Mamun MA, Griffiths MD. Prevalence of depression in Uganda: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one. 2022;17:e0276552.

Bolton P, Wilk CM, Ndogoni L. Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria. Soc psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:442.

Kinyanda E, Woodburn P, Tugumisirize J, Kagugube J, Ndyanabangi S, Patel V. Poverty, life events and the risk for depression in Uganda. Soc psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:35–44.

Perkins JM, Nyakato VN, Kakuhikire B, Tsai AC, Subramanian S, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insecurity, social networks and symptoms of depression among men and women in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional, population-based study. Public health Nutr. 2018;21:838–48.

Rathod SD, Roberts T, Medhin G, Murhar V, Samudre S, Luitel NP, et al. Detection and treatment initiation for depression and alcohol use disorders: facility-based cross-sectional studies in five low-income and middle-income country districts. BMJ open. 2018;8:e023421.

Smith ML, Kakuhikire B, Baguma C, Rasmussen JD, Perkins JM, Cooper-Vince C, et al. Relative wealth, subjective social status, and their associations with depression: Cross-sectional, population-based study in rural Uganda. SSM-Popul health. 2019;8:100448.

Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, Ferrari AJ, Hyman S, Laxminarayan R, Levin C, Lund C. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities. The Lancet. 2016;387:1672–85.

Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–32.

Bains N, Abdijadid S. Major Depressive Disorder. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2023.

Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:279–88.

Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Andersson G. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1219–29.

Chu A, Wadhwa R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Roopma Wadhwa declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

Horst WD, Preskorn SH. Mechanisms of action and clinical characteristics of three atypical antidepressants: venlafaxine, nefazodone, bupropion. J Affect Disord. 1998;51:237–54.

Hickie IB, Rogers NL. Novel melatonin-based therapies: potential advances in the treatment of major depression. Lancet. 2011;378:621–31.

Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ. How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:409–18.

Karrouri R, Hammani Z, Benjelloun R, Otheman Y. Major depressive disorder: Validated treatments and future challenges. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:9350–67.

Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, Cassano GB. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ect. 2004;20:13–20.

Schuch FB, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Borowsky C, Zimmermann AB, Rocha NS, Fleck MP. Exercise and severe major depression: effect on symptom severity and quality of life at discharge in an inpatient cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:25–32.

Méndez-Bustos P, Calati R, Rubio-Ramírez F, Olié E, Courtet P, Lopez-Castroman J. Effectiveness of Psychotherapy on Suicidal Risk: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Front Psychol. 2019;10:277.

D’Anci KE, Uhl S, Giradi G, Martin C. Treatments for the prevention and management of suicide: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:334–42.

Schrader C, Ross A. A Review of PTSD and Current Treatment Strategies. Mo Med. 2021;118:546–51.

Holt SR Alcohol use disorder: pharmacologic management. UpToDate. 2023.

Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;295:2003–17.

Martin GW, Rehm J. The effectiveness of psychosocial modalities in the treatment of alcohol problems in adults: a review of the evidence. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57:350–8.

Ray LA, Meredith LR, Kiluk BD, Walthers J, Carroll KM, Magill M. Combined Pharmacotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adults With Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208279.

Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19:93–107.

Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zheng Y, Biederman J, Bellgrove MA, et al. The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:789–818.

Briars L, Todd T. A Review of Pharmacological Management of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Pediatr Pharm Ther. 2016;21:192–206.

Markowitz JS, Straughn AB, Patrick KS. Advances in the pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: focus on methylphenidate formulations. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:1281–99.

Brown KA, Samuel S, Patel DR. Pharmacologic management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a review for practitioners. Transl Pediatr. 2018;7:36–47.

Stevens JR, Wilens TE, Stern TA. Using stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: clinical approaches and challenges. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15:26978.

Budur K, Mathews M, Adetunji B, Mathews M, Mahmud J. Non-stimulant treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2:44–8.

Fried EI, Robinaugh DJ. Systems all the way down: embracing complexity in mental health research. BMC Med. 2020;18:205.

Pettersson E, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Song J, Agrawal A, Børglum A, et al. Genetic influences on eight psychiatric disorders based on family data of 4 408 646 full and half-siblings, and genetic data of 333 748 cases and controls. Psychological Med. 2019;49:1166–73.

Levey DF, Stein MB, Wendt FR, Pathak GA, Zhou H, Aslan M, et al. Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in> 1.2 million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nat Neurosci 2021;24:954–63.

Mullins N, Kang J, Campos AI, Coleman JR, Edwards AC, Galfalvy H, et al. Dissecting the shared genetic architecture of suicide attempt, psychiatric disorders, and known risk factors. Biol psychiatry. 2022;91:313–27.

Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Klengel T, Atkinson EG, Chen C-Y, Choi KW, et al. International meta-analysis of PTSD genome-wide association studies identifies sex-and ancestry-specific genetic risk loci. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4558.

Lam M, Chen C-Y, Li Z, Martin AR, Bryois J, Ma X, et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1670–8.

Walters RK, Polimanti R, Johnson EC, McClintick JN, Adams MJ, Adkins AE, et al. Transancestral GWAS of alcohol dependence reveals common genetic underpinnings with psychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1656–69.

Davies MN, Verdi S, Burri A, Trzaskowski M, Lee M, Hettema JM, et al. Generalised anxiety disorder–a twin study of genetic architecture, genome-wide association and differential gene expression. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134865.

Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J, Mattheisen M, Als TD, Agerbo E, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:63–75.

Fatumo S, Mugisha J, Soremekun OS, Kalungi A, Mayanja R, Kintu C, et al. Uganda Genome Resource: A rich research database for genomic studies of communicable and non-communicable diseases in Africa. Cell Genomics. 2022;2:100209.

Asiki G, Murphy G, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Seeley J, Nsubuga RN, Karabarinde A, et al. The general population cohort in rural south-western Uganda: a platform for communicable and non-communicable disease studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:129–41.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33.

Kinyanda E, Hoskins S, Nakku J, Nawaz S, Patel V. Prevalence and risk factors of major depressive disorder in HIV/AIDS as seen in semi-urban Entebbe district, Uganda. BMC psychiatry. 2011;11:1–9.

Gurdasani D, Carstensen T, Fatumo S, Chen G, Franklin CS, Prado-Martinez J, et al. Uganda Genome Resource Enables Insights into Population History and Genomic Discovery in Africa. Cell. 2019;179:984–1002.e36.

Mugisha J, Muyinda H, Wandiembe P, Kinyanda E. Prevalence and factors associated with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder seven years after the conflict in three districts in northern Uganda (The Wayo-Nero Study). BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:170.

Koenen K, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin K, Bromet E, Stein D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological Med. 2017;47:2260–74.

Bifftu BB, Tiruneh BT, Dachew BA, Guracho YD. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in the general population of Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment health Syst. 2021;15:1–12.

Mugisha J, Muyinda H, Kagee A, Wandiembe P, Kiwuwa SM, Vancampfort D, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempt: associations with psychiatric disorders and HIV/AIDS in post-conflict Northern Uganda. Afr health Sci. 2016;16:1027–35.

Glantz MD, Bharat C, Degenhardt L, Sampson NA, Scott KM, Lim CC, et al. The epidemiology of alcohol use disorders cross-nationally: Findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Addictive Behav. 2020;102:106128.

Kabwama SN, Ndyanabangi S, Mutungi G, Wesonga R, Bahendeka SK, Guwatudde D. Alcohol use among adults in Uganda: findings from the countrywide non-communicable diseases risk factor cross-sectional survey. Glob health action. 2016;9:31302.

Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169–84.

Mugisha J, Byansi PK, Kinyanda E, Bbosa RS, Damme TV, Vancampfort D. Moderate to severe generalized anxiety disorder symptoms are associated with physical inactivity in people with HIV/AIDS: a study from Uganda. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;32:170–5.

Adeoti AO, Dada M, Elebiyo T, Fadare J, Ojo O. Survey of antiretroviral therapy adherence and predictors of poor adherence among HIV patients in a tertiary institution in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:277.

Wamulugwa J, Kakooza A, Kitaka SB, Nalugya J, Kaddumukasa M, Moore S, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among Ugandan children; a cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc psychiatry Ment health. 2017;11:1–7.

Kivumbi A. Prevalence and factors associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among patients with substance use disorders attending Butabika Hospital, Kampala: Makerere University; 2022.

Organization WH. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018: World Health Organization; 2019.

Wagman JA, Nabukalu D, Miller AP, Wawer MJ, Ssekubugu R, Nakowooya H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of men’s and women’s alcohol use in agrarian, trading and fishing communities in Rakai, Uganda. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240796.

Gum AM, King-Kallimanis B, Kohn R. Prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance-abuse disorders for older Americans in the national comorbidity survey-replication. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:769–81.

Beesdo K, Pine DS, Lieb R, Wittchen H-U. Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen psychiatry. 2010;67:47–57.

McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1027–35.

Jalnapurkar I, Allen M, Pigott T. Sex differences in anxiety disorders: A review. J. Psychiatry Depress Anxiety. 2018;4:3–16.

Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Body mass index and risk of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:615–25.

Zhang J, Yan F, Li Y, McKeown RE. Body mass index and suicidal behaviors: a critical review of epidemiological evidence. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:147–60.

Gearhardt AN, Waller R, Jester JM, Hyde LW, Zucker RA. Body mass index across adolescence and substance use problems in early adulthood. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2018;32:309.

Cummings JR, Ray LA, Tomiyama AJ. Food–alcohol competition: As young females eat more food, do they drink less alcohol? J health Psychol. 2017;22:674–83.

Tantawy S, Karamat NI, Al Gannas RS, Khadem SA, Kamel DM. Exploring the relationship between body mass index and anxiety status among Ahlia University Students. Open Access Macedonian J Med Sci. 2020;8:20–5.

Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2010;34:407–19.

de Wit L, Have MT, Cuijpers P, de Graaf R. Body Mass Index and risk for onset of mood and anxiety disorders in the general population: Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2 (NEMESIS-2). BMC psychiatry. 2022;22:1–11.

Prigge R, Jackson C. P43 The association between depression and subsequent hypertension–a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2017.

Jeon SW, Chang Y, Lim S-W, Cho J, Kim H-N, Kim K-B, et al. Bidirectional association between blood pressure and depressive symptoms in young and middle-age adults: a cohort study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e142.

Chen Q, Hartman CA, Haavik J, Harro J, Klungsøyr K, Hegvik T-A, et al. Common psychiatric and metabolic comorbidity of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2018;13:e0204516.

Paloyelis Y, Asherson P, Mehta MA, Faraone SV, Kuntsi J. DAT1 and COMT effects on delay discounting and trait impulsivity in male adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2414–26.

Luman M, Tripp G, Scheres A Testing hypotheses of altered reinforcement sensitivity in ADHD: a research agenda. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19.

Mdege ND, Makumbi FE, Ssenyonga R, Thirlway F, Matovu JK, Ratschen E, et al. Tobacco smoking and associated factors among people living with HIV in Uganda. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:1208–16.

Boua PR, Soo CC, Debpuur C, Maposa I, Nkoana S, Mohamed SF, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of tobacco and alcohol use in four sub-Saharan African countries: a cross-sectional study of middle-aged adults. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1126.

Öncü BK, Kişlak ŞT. Marital Adjustment and Marital Conflict in Individuals Diagnosed with ADHD and Their Spouses. Arch Neuropsychiatry. 2022;59:127.

Huynh-Hohnbaum A-LT, Benowitz S. Effects of adult ADHD on intimate partnerships. J Fam Soc Work. 2022;25:169–84.

Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, Nolen W, Beekman A. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scandinavica. 2010;122:184–91.

Maslej MM, Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Andrews PW, Mulsant BH. Individual differences in response to antidepressants: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials. JAMA psychiatry. 2020;77:607–17.

Drevets WC, Wittenberg GM, Bullmore ET, Manji HK. Immune targets for therapeutic development in depression: towards precision medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:224–44.

Cai H, Xie X-M, Zhang Q, Cui X, Lin J-X, Sim K, et al. Prevalence of suicidality in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Front psychiatry. 2021;12:690130.

Zhou Y, Cao Z, Yang M, Xi X, Guo Y, Fang M, et al. Comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and its association with quality of life in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40511.

Cho S-J, Hong JP, Lee J-Y, Im JS, Na K-S, Park JE, et al. association between DSM-IV anxiety disorders and suicidal behaviors in a community sample of South Korean adults. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13:595.

Kar N, Bastia BK. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents after a natural disaster: a study of comorbidity. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:1–7.

Fuller T, Reus V. Shared Genetics of Psychiatric Disorders. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the Uganda Genome Resource participants who agreed to participate in this study. We also thank the following research assistants who collected the data: Teddy Ayikoru, Nickson Mutaasa, Peter Bisaso, Sandra Namwebya, and Peter Kazibwe.

Funding

A.K. is a Wellcome Early Career Fellow [grant number: 227053/Z/23/Z]. Segun Fatumo is supported by both the Wellcome Trust [grant number: 220740/Z/20/Z] and the National Institute of Mental Health [grant number: 1R01MH134468]. This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement, through core funding to the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit. Cathryn Lewis is part-funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Karoline Kuchenbaecker has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. 948561). Funding sources had no role in the conduct or reporting of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, AK, SF, EK, DHA; Data collection, AK, SF, RSM, EK, TO, KF, PA, AK, JM, MN; BK; Data analysis, AK, WS; writing – original draft, AK; resources, SF, PK, MN, JM, and RM; critical review, all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalungi, A., Kinyanda, E., Akena, D.H. et al. Prevalence and correlates of common mental disorders among participants of the Uganda Genome Resource: Opportunities for psychiatric genetics research. Mol Psychiatry (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02665-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02665-8

- Springer Nature Limited