Abstract

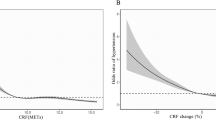

Established evidence has indicated a negative correlation between cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) and hypertension risk. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to investigate the categorical and dose–response relationship between CRF and hypertension risk and the effects of CRF changes on hypertension risk reduction. The PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases were searched for relevant studies. The summarized relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated using the DerSimonian and Laird random effect model, and the dose–response relationship between CRF and hypertension risk was characterized using generalized least-squares regression and restricted cubic splines. Nine cohorts describing 110,638 incident hypertension events among 1,618,067 participants were included in this study. Compared with the lowest category of CRF, the RR of hypertension was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.56–0.70) for the highest CRF category and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.80–0.91) for the moderate category of CRF. For a 1-metabolic equivalent increment in CRF, the pooled RR of hypertension was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90–0.94) in the total population. The RR of hypertension was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.64–0.79) for participants with CRF increased compared with those whose CRF was decreased over time. In conclusion, our meta-analysis supports the widely held notion of a negative dose-dependent relationship between CRF and hypertension risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. A global brief on hypertension: Silent killer, global public health crisis. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/global_brief_hypertension/en/, 2013.

Liu X, Zhang D, Liu Y, Sun X, Han C, Wang B, et al. Dose-response association between physical activity and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Hypertension. 2017;69:813–20.

Huai P, Xun H, Reilly KH, Wang Y, Ma W, Xi B. Physical activity and risk of hypertension: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Hypertension. 2013;62:1021–6.

Noonan V, Dean E. Submaximal exercise testing: clinical application and interpretation. Phys Ther. 2000;80:782–807.

Skinner JS, Wilmore KM, Krasnoff JB, Jaskolski A, Jaskolska A, Gagnon J, et al. Adaptation to a standardized training program and changes in fitness in a large, heterogeneous population: the HERITAGE Family Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:157–61.

DeFina LF, Haskell WL, Willis BL, Barlow CE, Finley CE, Levine BD, et al. Physical activity versus cardiorespiratory fitness: two (partly) distinct components of cardiovascular health? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57:324–9.

Gando Y, Sawada SS, Kawakami R, Momma H, Shimada K, Fukunaka Y, et al. Combined association of cardiorespiratory fitness and family history of hypertension on the incidence of hypertension: a long-term cohort study of Japanese males. Hypertension Res Off J Jpn Soc Hypertension. 2018;41:1063–9.

Kunutsor SK, Kurl S, Laukkanen JA. Association of oxygen uptake at ventilatory threshold with risk of incident hypertension: a long-term prospective cohort study. J Hum hypertension. 2017;31:654–6.

Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Interactive effects of physical fitness and body mass index on the risk of hypertension. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:210–6.

Carnethon MR, Gidding SS, Nehgme R, Sidney S, Jacobs DR, Liu K. Cardiorespiratory fitness in young adulthood and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors. JAMA. 2003;290:3092–100.

Liu X, Zhang D, Liu Y, Sun X, Hou Y, Wang B, et al. A J-shaped relation of BMI and stroke: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of 4.43 million participants. Nutr Metab Cardiovascular Dis. 2018;28:1092–9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

Faselis C, Doumas M, Kokkinos JP, Panagiotakos D, Kheirbek R, Sheriff HM, et al. Exercise capacity and progression from prehypertension to hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60:333–8.

Juraschek SP, Blaha MJ, Whelton SP, Blumenthal R, Jones SR, Keteyian SJ, et al. Physical fitness and hypertension in a population at risk for cardiovascular disease: the Henry Ford ExercIse Testing (FIT) Project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001268.

Carnethon MR, Evans NS, Church TS, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, Jacobs DR, et al. Joint associations of physical activity and aerobic fitness on the development of incident hypertension: coronary artery risk development in young adults. Hypertension. 2010;56:49–55.

Jae SY, Heffernan KS, Yoon ES, Park SH, Carnethon MR, Fernhall B, et al. Temporal changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and the incidence of hypertension in initially normotensive subjects. Am J Hum Biol Off J Hum Biol Counc. 2012;24:763–7.

Jae SY, Kurl S, Laukkanen JA, Lee CD, Choi YH, Fernhall B, et al. Relation of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and cardiorespiratory fitness to risk of systemic hypertension in men. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1714–9.

Barlow CE, LaMonte MJ, Fitzgerald SJ, Kampert JB, Perrin JL, Blair SN, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness is an independent predictor of hypertension incidence among initially normotensive healthy women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:142–50.

Chase NL, Sui X, Lee DC, Blair SN. The association of cardiorespiratory fitness and physical activity with incidence of hypertension in men. Am J Hypertension. 2009;22:417–24.

Shook RP, Lee DC, Sui X, Prasad V, Hooker SP, Church TS. Cardiorespiratory fitness reduces the risk of incident hypertension associated with a parental history of hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;59:1220–4.

Rankinen T, Church TS, Rice T, Bouchard C, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness, BMI, and risk of hypertension: the HYPGENE study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1687–92.

Banda JA, Clouston K, Sui X, Hooker SP, Lee CD, Blair SN. Protective health factors and incident hypertension in men. Am J Hypertension. 2010;23:599–605.

Sui X, Sarzynski MA, Lee DC, Lavie CJ, Zhang J, Kokkinos PF, et al. Longitudinal patterns of cardiorespiratory fitness predict the development of hypertension among men and women. Am J Med. 2017;130:469–476.e2.

Jae SY, Kurl S, Franklin BA, Laukkanen JA. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness predict incident hypertension: a population-based long-term study. Am J Hum Biol 2017;29:1–5.

Lee DC, Sui X, Church TS, Lavie CJ, Jackson AS, Blair SN. Changes in fitness and fatness on the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:665–72.

Holmlund T, Ekblom B, Börjesson M, Andersson G, Wallin P, Ekblom-Bak E. Association between change in cardiorespiratory fitness and incident hypertension in Swedish adults. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020.

Wells BS, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

American College of Sports Medicine, ACSM’s Metabolic Calculations Handbook, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA,, 2006.

Andersen LB. A maximal cycle exercise protocol to predict maximal oxygen uptake. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5:143–6.

Hartemink N, Boshuizen HC, Nagelkerke NJ, Jacobs MA, van Houwelingen HC. Combining risk estimates from observational studies with different exposure cutpoints: a meta-analysis on body mass index and diabetes type 2. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1042–52.

Hamling J, Lee P, Weitkunat R, Ambuhl M. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat Med. 2008;27:954–70.

Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose–response data. Stata J. 2006;6:40–57.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88.

Greenland S. Dose-response and trend analysis in epidemiology: alternatives to categorical analysis. Epidemiology. 1995;6:356–65.

Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29:1037–57.

Bekkering GE, Harris RJ, Thomas, Mayer AM, Beynon R, Ness AR, et al. How much of the data published in observational studies of the association between diet and prostate or bladder cancer is usable for meta-analysis? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1017–26.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326:219.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat Med. 2004;23:1663–82.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2009;301:2024–35.

Qiu S, Cai X, Yang B, Du Z, Cai M, Sun Z. et al. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Obesity. 2019;27:315–24.

Sieverdes JC, Sui X, Lee DC, Church TS, McClain A, Hand GA, et al. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in a prospective study of men. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:238–44.

Bouchard C, Daw EW, Rice T, Perusse L, Gagnon J, Province MA, et al. Familial resemblance for VO2max in the sedentary state: the HERITAGE family study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:252–8.

Repka CP, Hayward R. Oxidative stress and fitness changes in cancer patients after exercise training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:607–14.

Blond MB, Rosenkilde M, Gram AS, Tindborg M, Christensen AN, Quist JS, et al. How does 6 months of active bike commuting or leisure-time exercise affect insulin sensitivity, cardiorespiratory fitness and intra-abdominal fat? A randomised controlled trial in individuals with overweight and obesity. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:1183–92.

Wedell-Neergaard AS, Krogh-Madsen R, Petersen G, Hansen AM, Pedersen BK, Lund R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and the metabolic syndrome: Roles of inflammation and abdominal obesity. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0194991.

Howe AS, Skidmore PM, Parnell WR, Wong JE, Lubransky AC, Black KE. Cardiorespiratory fitness is positively associated with a healthy dietary pattern in New Zealand adolescents. Public health Nutr. 2016;19:1279–87.

Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Beckie TM, Brubaker PH, Church TS, Forman DE, et al. The importance of cardiorespiratory fitness in the United States: the need for a national registry: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:652–62.

Lavie CJ, McAuley PA, Church TS, Milani RV, Blair SN. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1345–54.

Ortega R, Grandes G, Sanchez A, Montoya I, Torcal J. Cardiorespiratory fitness and development of abdominal obesity. Preventive Med. 2019;118:232–7.

Konigstein K, Infanger D, Klenk C, Hinrichs T, Rossmeissl A, Baumann S, et al. Does obesity attenuate the beneficial cardiovascular effects of cardiorespiratory fitness? Atherosclerosis. 2018;272:21–26.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334–59.

Department of Health. Start Active, Stay Active: A Report on Physical Activity from the Four Home Countries’ Chief Medical Officers, Crown, London, 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, C., Zhang, D., Chen, S. et al. The association of cardiorespiratory fitness and the risk of hypertension: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens 36, 744–752 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00567-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00567-8

- Springer Nature Limited