Abstract

Thermal stabilization of proteins after ligand binding provides an efficient means to assess the binding of small molecules to proteins. We show here that in combination with quantitative mass spectrometry, the approach allows for the systematic survey of protein engagement by cellular metabolites and drugs. We profiled the targets of the drugs methotrexate and (S)-crizotinib and the metabolite 2′3′-cGAMP in intact cells and identified the 2′3′-cGAMP cognate transmembrane receptor STING, involved in immune signaling.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lee, J. & Bogyo, M. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 118–126 (2013).

Kambe, T., Correia, B.E., Niphakis, M.J. & Cravatt, B.F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10777–10782 (2014).

Huber, K.V.M. et al. Nature 508, 222–227 (2014).

Feng, Y. et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1036–1044 (2014).

Lomenick, B. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21984–21989 (2009).

Niesen, F.H., Berglund, H. & Vedadi, M. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2212–2221 (2007).

Fedorov, O. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 20523–20528 (2007).

Martinez Molina, D. et al. Science 341, 84–87 (2013).

Savitski, M.M. et al. Science 346, 1255784 (2014).

Gad, H. et al. Nature 508, 215–221 (2014).

Dayon, L. et al. Anal. Chem. 80, 2921–2931 (2008).

Parlanti, E., Locatelli, G., Maga, G. & Dogliotti, E. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1569–1577 (2007).

Allegra, C.J. et al. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 9720–9726 (1985).

Ablasser, A. et al. Nature 498, 380–384 (2013).

Cai, X., Chiu, Y.-H. & Chen, Z.J. Mol. Cell 54, 289–296 (2014).

Lambert, J.-P. et al. Nat. Methods 10, 1239–1245 (2013).

Yoh, S.M. et al. Cell 161, 1293–1305 (2015).

Gilar, M., Olivova, P., Daly, A.E. & Gebler, J.C. J. Sep. Sci. 28, 1694–1703 (2005).

Olsen, J.V. et al. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 2010–2021 (2005).

Perkins, D.N., Pappin, D.J.C., Creasy, D.M. & Cottrell, J.S. Electrophoresis 20, 3551–3567 (1999).

Colinge, J., Masselot, A., Giron, M., Dessingy, T. & Magnin, J. Proteomics 3, 1454–1463 (2003).

Burkard, T.R. et al. BMC Syst. Biol. 5, 17 (2011).

Breitwieser, F.P. et al. J. Prot. Res. 10, 2758–2766 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to W. Berger (Institute of Cancer Research, Vienna, Austria) for providing SW480 cells and P. Majek (CeMM, Vienna, Austria) for assistance with data processing. This work was supported by the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the European Union (FP7 259348, ASSET) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF F4711, MPN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.V.M.H. designed experiments and jointly performed them with K.M.O.; A.C.M. and K.L.B. performed mass spectrometry; C.S.H.T. and J.C. performed bioinformatics analysis; and K.V.M.H. and G.S.-F. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and participated in preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Data normalization.

Average thermal profiles are plotted for DMSO- and (S)-crizotinib-treated cells. Note that the two profiles (broken straight lines) are similar (no thermal shift) but imperfect. The two fitted sigmoid models are very close (dashed smooth lines), thus further indicating the absence of influence of (S)-crizotinib on the average thermal stability. Vertical arrows (only displayed for the DMSO sample for simplicity), expressed as shift in normalized coordinates, can be applied to spectra specific to a given protein for subsequent scoring of the whole dataset and can be regarded as a structural normalization considering the different protein content at each temperature.

Supplementary Figure 2 Known interactions between proteins found to be stabilized in experiments with intact SW480 cells.

Edge thickness represents interaction confidence. Data and graphical representation taken from STRING1.

Supplementary Figure 3 Original full-length anti-MTH1 western blots used for Figure 2b.

Data from SW480 intact cell experiments. (a) DMSO; (b) (S)-crizotinib. Asterisk indicates unspecific band.

Supplementary Figure 4 Melting-temperature profiles obtained for MTH1 (NUDT1) from SW480 cell lysate experiments.

Similar to intact cell experiments, treatment of SW480 cell extracts with (S)‑crizotinib leads to a stabilization of MTH1 (NUDT1). Data indicate one technical replicate.

Supplementary Figure 5 Kinases with differential melting profiles observed in cell lysates treated with 100 µM (S)-crizotinib.

Treatment of SW480 cell lysates with 100 µM (S)‑crizotinib leads to a stabilization of (a) PI3K-beta (PIK3CB) and (b) CDK2. Data indicate one technical replicate.

Supplementary Figure 6 Original full-length anti-DHFR western blots used for Figure 2d.

Data from K562 intact cell experiments. (a) DMSO; (b) methotrexate.

Supplementary Figure 7 Original full-length anti-STING western blots used for Figure 2f.

Data from RAW intact cell experiments. (a) Water; (b) 2ʹ3ʹ-cGAMP.

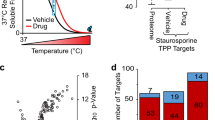

Supplementary Figure 8 Definition of the area score.

The area score considers a signed area between the vehicle-treated sample curve and the compound-treated curve.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–8, Supplementary Tables 1–5 and Supplementary Note 1 (PDF 2462 kb)

Source data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, K., Olek, K., Müller, A. et al. Proteome-wide drug and metabolite interaction mapping by thermal-stability profiling. Nat Methods 12, 1055–1057 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3590

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3590

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Learning the metabolic language of cancer

Nature (2023)

-

The emerging role of mass spectrometry-based proteomics in drug discovery

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2022)

-

Host and microbiota metabolic signals in aging and longevity

Nature Chemical Biology (2021)

-

Callyspongiolide kills cells by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction via cellular iron depletion

Communications Biology (2021)

-

The analog of cGAMP, c-di-AMP, activates STING mediated cell death pathway in estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer cells

Apoptosis (2021)