Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin disease with no well-delineated cause or effective cure. Here we show that the p53 family member p63, specifically the ΔNp63, isoform has a key role in driving keratinocyte activation in AD. We find that overexpression of ΔNp63 in transgenic mouse epidermis results in a severe skin phenotype that shares many of the key clinical, histological and molecular features associated with human AD. This includes pruritus, epidermal hyperplasia, aberrant keratinocyte differentiation, enhanced expression of selected cytokines and chemokines and the infiltration of large numbers of inflammatory cells including type 2 T-helper cells – features that are highly representative of AD dermatopathology. We further demonstrate several of these mediators to be direct transcriptional targets of ΔNp63 in keratinocytes. Of particular significance are two p63 target genes, IL-31 and IL-33, both of which are key players in the signaling pathways implicated in AD. Importantly, we find these observations to be in good agreement with elevated levels of ΔNp63 in skin lesions of human patients with AD. Our studies reveal an important role for ΔNp63 in the pathogenesis of AD and offer new insights into its etiology and possible therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that commonly afflicts the pediatric population and has been increasing in prevalence worldwide.1, 2 Although the etiology of AD is complex, studies suggest that immune dysregulation and impaired barrier function are the two salient features of this disease.3, 4 Clinically, AD is characterized by recurrent, erythematous skin lesions, which are intensely pruritic and are at a heightened risk for microbial colonization. AD skin lesions exhibit distinct features including epidermal hyperplasia, defective terminal differentiation of keratinocytes and an activated immune response characterized by infiltrates of T-helper subset (Th2) cells and elevated expression of cytokines, chemokines and other inflammatory molecules.3, 5 Indeed, several Th2 cytokines and chemokines including IL-33, IL-25, IL-4, IL-13 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) are present within AD skin lesions and are thought to have important roles in this disease.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

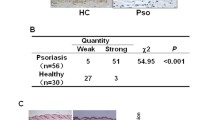

The transcriptional regulator, p63, is an epithelial-enriched lineage-specific factor that has important roles in stem cell renewal, morphogenesis and in directing differentiation programs.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 The critical developmental role of p63 is epitomized by the lack of mature skin in p63-null animals, a phenotype that is mirrored in human syndromes with ectodermal dysplasia caused by germ-line mutations in the human p63 gene.18 Beyond the well-established function of p63 in morphogenesis, growing evidence supports a role for this factor in a variety of epithelial diseases. Indeed, p63 is overexpressed in many squamous tumors including those of the head and neck, lung and skin19, 20, 21 and dysregulated expression of p63 has been reported in psoriasis.22, 23, 24 One challenge facing these p63-centric studies is the complexity of the Tp63 gene, which generates two major isoforms; TAp63 and ΔNp63, each of which exists as α, β and γ variants that differ in their C-terminal domains. However, it is becoming clear that it is the ΔNp63α isoform that is highly expressed in keratinocytes and is indispensable for skin development, as demonstrated by transcriptomic and ΔNp63 isoform-specific knockout studies.25, 26, 27, 28

Here we report that overexpression of ΔNp63 in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in a skin phenotype that shares many of the key features associated with human AD skin lesions. ΔNp63 transgenic animals develop pruritus, epidermal hyperplasia, altered terminal differentiation and a reactive inflammatory microenvironment marked by macrophage and mast cell infiltrations and polarized Th2 cells. Consistent with these pathophysiological changes, ΔNp63 transgenic epidermis shows a marked increase in many cytokines and chemokines, including IL-33 and IL-31, key players that are well-established mediators of the skin lesions and severe pruritus observed in AD.7, 29 We show that IL-33 and IL-31, among other cytokines and chemokines, are direct transcriptional targets of ΔNp63 in keratinocytes. Finally, we demonstrate elevated expression levels of the ΔNp63 isoforms of p63 in human AD lesional skin. Together, our results provide compelling new evidence for the potential role of ΔNp63-driven keratinocyte activation as a critical precursor in AD development.

Results

Mice overexpressing ΔNp63 in the epidermis develop inflammatory skin lesions resembling human AD

Targeted expression of ΔNp63α to the basal keratinocytes of adult mouse skin was achieved using an inducible K5-tTA/pTRE-HA-ΔNp63α bi-transgenic (ΔNp63BG) model system, in which the ΔNp63 transgene contains an N-terminal HA-epitope tag17, 30 (see also Materials and Methods). To suppress transgene induction during embryogenesis, pregnant dams were administered doxycycline in rodent chow. Transgene expression was then induced in ΔNp63BG mice at weaning by doxycycline withdrawal. Utilizing two different transgenic founder lines, we found that in contrast to control animals, which displayed no obvious phenotype, all ΔNp63BG mice developed alopecia, erythema and skin erosions over the course of 3–4 months of transgene expression (Figure 1a). Skin lesions were reproducibly found on the head, neck, back and abdominal areas of the animals – anatomical regions that are accessible and hence prone to scratching and rubbing (see representative examples in Supplementary Figure 1A). Interestingly, with continued ΔNp63 transgene expression, lesions progressed and became more extensive, developing into lichenified skin lesions.

Development of dermatitis in ΔNp63 transgenic mice. (a) Gross morphology showing progression of dermatitis lesions in adult ΔNp63BG mice at various stages as indicated after induction of ΔNp63 transgene expression. (b) Clinical skin severity scores of dermatitis in control (n=15) and transgenic mice (n=15). Quantitative evaluations of clinical scores were based on the criteria described in the Materials and Methods. (c) Spontaneous scratching was counted in wild-type and bi-transgenic mice after 13 weeks of transgene induction for 5 min (n=10). Data are represented as mean±S.D. of three experiments. *P<0.001, Student’s t-test. (d) Total serum IgE levels were measured by ELISA (n=6). Data are represented as mean±S.E. *P<0.001, Student’s t-test

To characterize the magnitude of the dermatitis of the affected animals, we utilized a clinical skin severity-scoring system (see Materials and Methods). We observed that ΔNp63BG mice displayed increased severity scores over time as compared with control mice with the first signs of the phenotype appearing ~7 weeks after transgene induction (Figure 1b). In addition to the widespread dermatitis, transgenic animals developed severe pruritus. Indeed, ΔNp63BG animals exhibited constant and intense scratching of affected areas (Figure 1c). Interestingly, in agreement with the worsening skin phenotype and clinical score, serum IgE levels of ΔNp63BG animals at 18 weeks were approximately five times higher than control mice (Figure 1d). These findings are similar to what is observed in human subjects with extrinsic (or atopic) AD.31, 32 Taken together, these results suggest that epidermal overexpression of ΔNp63 in mice share many clinical features of AD.

ΔNp63 transgenic mice exhibit epidermal hyperplasia and abnormalities in terminal differentiation

Histologic examination of adult ΔNp63 transgenic skin lesions revealed marked epidermal thickening accompanied by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, hypogranulosis and acanthosis (Supplementary Figure 1B). To examine the expression levels of the HA-ΔNp63 transgene, we performed western blot analysis with skin extracts of wild-type (WT) control and ΔNp63BG animals. Antibodies directed against the HA-epitope tag confirmed robust transgene expression in the ΔNp63BG mice (Supplementary Figure 1C). Moreover, anti-ΔNp63 antibodies showed approximately threefold increase in overall ΔNp63 levels in ΔNp63BG skin, compared with WT mouse skin (Supplementary Figure 1C). To further characterize the epidermal phenotype, we next utilized a battery of well-established keratinocyte differentiation markers. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1D, skin lesions from ΔNp63BG mice showed significant alterations in the expression of these markers. Specifically, keratin 14 (K14), normally confined to the basal layer of the epidermis as seen in WT controls, was expressed throughout all epidermal layers in the ΔNp63BG mice – a result consistent with epidermal hyperplasia. In addition, the spinous layer was expanded in ΔNp63BG mice as revealed by staining for keratin 1 (K1) (Supplementary Figure 1D). To determine whether there were defects in terminal epidermal differentiation, we evaluated the expression patterns of filaggrin (Flg), loricrin (Lor) and involucrin (Ivl). Compared with controls, ΔNp63BG skin showed a modest reduction in both protein and mRNA expression levels of these major terminal differentiation markers (Supplementary Figure 1D and 1E, respectively). These results indicate that enhanced expression of ΔNp63 in the basal layer of the epidermis results in an expansion of both the basal and spinous layers of the epidermis, but inhibits the final stages of terminal differentiation – a phenotype strikingly similar to lesional skin of patients with AD.33, 34

Analysis of transcriptomic changes in ΔNp63 transgenic epidermis

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying the AD-like phenotype in ΔNp63BG mice, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) on epidermis isolated from transgenic and WT mice at post-natal day 4 (P4). Although these young transgenic animals did not display a full-blown skin phenotype at this time point, they do exhibit visible phenotypic signs commonly associated with AD, including dry, inflamed skin as a consequence of ΔNp63 transgene induction that was initiated during the early stages of embryogenesis.17 We reasoned that this earlier time point would allow us a better glimpse into the direct effects of overexpression of ΔNp63 on the development of the AD phenotype. Our results revealed major alterations in the global transcriptional profile of ΔNp63BG epidermis, with a total of 1901 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Of the DEGs identified, 236 genes demonstrated greater than 4-fold upregulation and 313 genes were greater than 4-fold downregulated compared with WT epidermis (Supplementary Table 1). We identified significant enrichment of several signaling pathways, which have been linked to AD, including the IL10, IL6, NFκβ and TLR signaling pathways35, 36, 37, 38 (Figure 2a and b). We also observed enrichment of a number of annotated biological functions including ‘inflammatory responses’, ‘keratinization’ and ‘dermatological diseases and conditions’ – in good agreement with processes that are intimately associated with AD pathogenesis (Figure 2c). Taken together, the early transcriptional changes observed in the transgenic mouse epidermis further support the notion that the phenotypic alterations seen in the ΔNp63BG mouse model are indeed AD-like.

Global transcription changes precede immune-mediated inflammatory skin lesions of ΔNp63 transgenic mice. (a) Canonical signaling pathways significantly enriched among documented annotations for the 1901 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in transgenic epidermis. (b) Global gene expression behavior of significant and near-significant. (fold-change >4) DEGs-populating key pathways is highlighted (orange) and underlined in panel (a). (c) Heatmap depicting the relative expression behavior of selected DEGs involved in dermatitis (D), keratinocyte differentiation (K) and inflammation (I) using IPA annotations (shown in blue). WT, wild-type; BG, bi-transgenic

Th2 and IL-31 signaling in ΔNp63 transgenic lesional skin

Given the strong link between AD and the Th2 pathway,2, 39 we mined our RNA-seq data to examine the expression levels of major cytokines and chemokines that are associated with Th2 inflammation. We observed specific upregulation of several Th2 promoting and/or downstream cytokines and chemokines including IL-33 and CCL22 in ΔNp63BG skin samples (Figure 2c). As this data were from RNA-seq analysis of younger (P4) mice, we also performed quantitative RT-PCR in skin samples from adult transgenic and control mice. This analysis confirmed the preferential induction of Th2 cytokines, chemokines and Th2-promoting cytokines including IL-33, IL-25, TSLP, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, CCL17 and CCL22 (Figure 3a) in adult ΔNp63BG skin with a full-blown phenotype. In contrast, no alterations in the expression levels of Th1 or Th17-type cytokines were observed (Figure 3b). Interestingly, IL-33, a known inducer of Th2 cytokines and an established player in the pathogenesis of AD,6, 7, 8, 40 was one of the most highly induced cytokines in the transgenic epidermis during both the early and later stages of the appearance of the skin phenotype (Figures 2c and 3a, respectively). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining confirmed enhanced expression of IL-33 protein in ΔNp63BG mouse skin (Figure 3c).

Specific induction of Th2 cytokines and chemokines and IL-31 signaling in transgenic skin. (a) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression levels of genes known to promote or be induced by Th2 responses in adult control and transgenic mouse skin. Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Data are represented as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments. *P<0.001, **P<0.002, ***P<0.005, Student’s t-test. (b) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression levels of genes known to promote Th1 and Th17 responses in adult control and transgenic mouse skin. Data are represented as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of dorsal skin sections using anti-K5 and IL-33 antibodies. Dotted white lines indicate the epidermal-dermal junction. (d) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of genes involved in IL-31 signaling in adult transgenic and wild-type mouse skin. Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Data are represented as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments. ***P<0.001; **P<0.002, *P<0.005, Student’s t-test. Scale bar: 75 μm

In addition to the elevated expression levels of Th2 cytokines, the RNA-seq data also revealed increased expression of molecular components in the IL-31 signaling pathway, an important mediator of pruritus in a number of skin diseases including AD.29, 41, 42, 43 IL-31 primarily signals through a heterodimeric receptor complex composed of IL-31 receptor alpha (IL-31ra) and the Oncostatin M Receptor (OSMR), both of which were significantly elevated in P4 ΔNp63BG epidermis (Figure 2c). As this represented an early time point, prior to the overt scratching prevalent only in adult mice, we next examined mRNA levels of IL-31, IL-31ra and OSMR in adult transgenic lesional and WT mouse skin. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated significant upregulation of all three genes, including IL-31, in ΔNp63αBG adult skin compared with control skin (Figure 3d).

ΔNp63 directly activates IL-31 and IL-33 signaling

To address whether ΔNp63 directly controlled expression of IL-31 and IL-33 signaling, we next investigated epigenomic data sets generated by the ENCODE project44 and p63 ChIP-sequencing experiments performed with normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK).45 We specifically focused on potential regulatory regions in NHEK cells that were (a) bound by p63, (b) enriched for chromatin modification signatures associated with enhancers (H3K4me1 and H3K4me2)46, 47, 48, 49 and active regulatory regions (H3K27ac)50 and (c) showed strong evolutionary sequence conservation. We reasoned that fulfillment of the above criterions would strongly suggest that a given genomic locus is a conserved and functional p63-binding site.

Focusing first on the IL-31-signaling pathway, we identified two regions within the human IL-31RA gene containing a potential p63-binding site (Figure 4a and b). Next, to find candidate homologous p63-binding sites within the mouse IL-31ra genomic locus, we scanned the genomic region for sequence-based predicted p63-binding sites aided by functional histone modification signatures (Figure 4c and d). This bioinformatics-based approach identified a region between exons 5 and 6 of the mouse IL-31ra gene, as a candidate p63-binding site (Figure 4d and e). To test whether p63 could bind to this intragenic region of the mouse IL-31ra gene, we performed ChIP experiments on mouse keratinocyte chromatin using two independent p63 antibodies followed by qPCR quantification. To ensure the specificity of the ChIP experiments, we included an upstream p63-responsive enhancer of the k14 gene51 and an intragenic region within the Cst10 gene, which does not contain a p63 response element, to serve as positive and negative controls, respectively (Figure 4g). Our qPCR results demonstrated a strong enrichment of the putative p63 response element in the IL-31ra gene relative to a random genomic locus (Figure 4g). Using a similar approach as described above for IL-31ra, we identified p63 response elements in the mouse IL-31, OSMR and IL-33 genes, which were confirmed by ChIP-qPCR (Figure 4f and g, respectively).

Direct regulation of IL-31 and IL-33 signaling by ΔNp63. (a) Snapshot of p63 binding at the human IL-31RA locus as demonstrated by ChIP-sequencing (light green=anti-p63, dark green=anti-p63α).45 (b) Histone modifications (orange=H3K4Me1; pink=H3K27Ac) and sequence conservation scores (PhyloP and PhastCons) in NHEK.67 (c) Snapshot of the mouse IL-31ra locus illustrating enrichment of active-chromatin-associated histone modifications.68 (d) The highest scoring-predicted p63 Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBS) (see Materials and Methods) is highlighted and magnified. Green bar height indicates predicted p63 binding site scores. (e) Histone marks and sequence conservation for the highest scoring predicted p63-binding site, located between exon 5 and 6 of the mouse IL-31ra gene, which is homologous to the p63-binding site identified in human (4A and 4B). (f) Left, snapshots of p63-binding sites (green boxes, as in panel a) in NHEK cells at IL-31, OSMR and IL-33 gene loci. Right, snapshots of predicted p63-binding sites at mouse IL-31, OSMR and IL-33 gene loci (green boxes). (g) ChIP-qPCR results using the ΔNp63-specific antibody (RR-14) and the p63α (H129) antibody in mouse keratinocytes confirms specific binding of p63 to the IL-31ra, IL-31, OSMR and IL-33 genomic loci at the predicted locations (illustrated in above panels). K14 and Cst10 serve as positive and negative controls, respectively. Values represent mean fold enrichment over random genomic loci±S.E. (h) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expression levels of IL-33, IL-31, IL-31ra and OSMR in ΔNp63α wild-type or ΔNp63αMUT overexpressing mouse keratinocytes as compared with the control (empty vector). Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Data are represented as mean±S.E. *P<0.001, **P<0.005, Student’s t-test

Next, to test the functional consequences of p63 binding to these potential regulatory elements, we transduced mouse keratinocytes with retroviral vectors expressing either WT ΔNp63α or a DNA-binding impaired mutant (ΔNp63αMUT)18, 51 and measured IL-31ra, IL-31, OSMR and IL-33 mRNA expression levels. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that mouse keratinocytes transduced only with WT ΔNp63, but not ΔNp63αMUT showed elevated mRNA expression levels of IL-31ra, IL-31, OSMR and IL-33 (Figure 4h). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that ΔNp63α can directly regulate the expression of key genes involved in IL-31 signaling, which might account for the pruritic phenotype observed in ΔNp63 transgenic animals and in AD patients. In parallel, elevated levels of ΔNp63 can also trigger Th2 inflammation, in part, by directly inducing the pro-Th2 cytokine, IL-33 and thus contributing to the AD phenotype.

Reversal of the AD skin phenotype in ΔNp63 transgenic mice upon suppression of transgene expression

Given the progressive nature of the AD-like skin lesions of the ΔNp63-overexpressing transgenic animals, we wondered if we could reverse the phenotype and severity of the skin lesions by repressing ΔNp63 transgene expression. Interestingly, on re-administration of doxycycline and subsequent transgene suppression, we observed a complete rescue of the AD skin phenotype in the ΔNp63BG mice. Indeed, after 6 weeks of transgene repression, ΔNp63BG animals displayed no obvious morphological signs of a skin phenotype (Figure 5a). Histological examination revealed no indications of epidermal hyperplasia, as demonstrated by both hematoxylin and eosin staining and examination of Ki67 expression levels, with the rescued ΔNp63BG (BG rescue) skin indistinguishable from WT littermates (Figure 5b). Furthermore, there were also no discernible defects in the keratinocyte terminal differentiation program in the ΔNp63BG rescue mice when compared with control mice as examined by immunofluorescence and qRT-PCR (Figure 5b and c). The restoration of a normal skin phenotype of the ΔNp63BG rescued animals was also accompanied by normal mRNA expression levels of genes involved in Th2, IL-33 or IL-31 signaling and serum IgE levels, similar to what was found in control mice (Figure 5c and d). Overall, these findings suggest that the restoration of normal physiological levels of ΔNp63 in the mouse epidermis is sufficient to reverse the AD-like skin phenotype.

Repression of ΔNp63 transgene expression rescues the dermatitis phenotype in transgenic animals. (a) Gross morphology showing amelioration of the AD skin lesions upon transgene repression. Four months after ΔNp63BG mice developed the AD skin lesions, animals were administered Dox to repress expression of the transgene. After 6 weeks of ΔNp63 transgene repression, ΔNp63BG showed no signs of the AD skin phenotype (ΔNp63BG Rescue). (b) Dorsal skin sections of ΔNp63BG Rescue (BG Rescue) and wild-type mice show similar expression patterns of the various terminal differentiation markers as well as similar Ki67 expression levels. (c) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of genes known to promote Th2 responses, genes involved in IL31 signaling and genes involved in keratinocyte terminal differentiation reveals levels in ΔNp63BG rescue (BG-AD Rescue) skin to be similar to wild-type, as compared with ΔNp63BG (BG-AD Lesional). (d) Total serums IgE levels in wild-type (WT) (n=6), ΔNp63BG (BG) (n=6) and ΔNp63BG Rescue (Rescue) (n=6) were measured by ELISA. Data are represented as mean±S.E. *P<0.005, **P<0.0001, Student’s t-test

Altered expression of ΔNp63 in human AD lesional skin

Based on the AD-like phenotype of the transgenic mice, we next sought to assess the expression levels of p63 in human AD patient samples. A previous microarray study on chronic AD skin lesions had demonstrated a 5.2-fold upregulation of TP63 gene expression levels compared with normal skin – however, this analysis was performed without isoform-specific probes for the TP63 gene.33 To determine specifically, which of the p63 isoforms were elevated in AD lesional skin, we performed immunofluorescence staining on normal non-atopic, and paired AD samples from both non-lesional and lesional skin using TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoform-specific antibodies. Although TAp63 expression was undetectable (data not shown), we found increased numbers of ΔNp63+-expressing cells in the AD lesional epidermis when compared with paired non-lesional and normal human skin (Figure 6a, lower panel and Supplementary Figure 2). To ensure that the elevated number of ΔNp63+ cells in AD patient epidermis was not due to increased cell numbers secondary to epidermal hyperplasia associated with AD, we performed quantitative analyses. Our results showed that p63+ nuclei accounted for 40% of total nuclei in normal and non-lesional skin, whereas p63+ cells accounted for a significantly larger percentage of nuclei (~80%, P=0.001) in AD lesional skin (Figure 6b). Analysis of AD patient lesional skin by qRT-PCR further demonstrated isoform-specific upregulation of ΔNp63 mRNA levels in comparison with that of normal skin (Figure 6c). Together these results confirmed that it is the ΔNp63 isoform that is predominantly expressed in the epidermis of AD lesional skin.

ΔNp63 expression in lesional skin from atopic dermatitis subjects. (a) Upper panel shows hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of normal human skin, AD non-lesional and lesional skin. Lower panel shows representative immunofluorescence staining of ΔNp63 isoform-specific expression in the epidermis of normal skin, AD non-lesional, AD lesional skin. Dotted white lines indicate the epidermal–dermal junction. Scale bar: 75 μm. (b) Quantification of the percentage of ΔNp63+ cells in normal human skin, AD non-lesional and lesional skin is shown. A total of 15 fields of view were used for quantification analysis on normal human skin (n=8), AD non-lesional skin (n=8) and AD lesional (n=8) skin samples. Data are represented as mean±S.D. (c) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of ΔNp63 and TAp63 in normal skin (n=5) and AD lesional skin (n=5). Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Data are represented as mean±S.E. *P=0.001, Student's t-test

Discussion

The pathophysiology of AD is complex and remains a subject of intense debate. A keratinocyte-centric view postulates that a breakdown of the epidermal barrier and/or aberrant epithelial activation has a pivotal role in AD development.31 An alternative hypothesis posits that AD is an allergic inflammatory disease caused by immune dysregulation that not only precedes but also acts as a driver of the skin barrier defects.4 In this scenario, infiltrating immune cells take center stage with an early telltale Th2 immune response, followed later by a broader participation from Th1 and Th22 cells, macrophages and mast cells. Regardless, it is clear that AD keratinocytes are integral cellular constituents of the adaptive and innate immune defects observed in this disease. Indeed, AD keratinocytes express high levels of cytokines such as, IL-25 and IL-33, and chemokines such as TLSP, which have important roles in sustaining the AD-interactive cellular network. The molecular mechanisms that drive this hyperactive keratinocyte phenotype, however, remain poorly understood.

Over the past several years, transgenic overexpression mouse models of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as TSLP, IL-4 and IL-33 have proven extremely valuable in examining the pathogenesis of AD. Although these studies have been very useful, they have failed to identify early events that trigger the release of these inflammatory molecules by the skin keratinocytes. In the present study, we identify a novel role for ΔNp63, an indispensable transcriptional regulator of keratinocyte development and differentiation, in the pathogenesis of AD. More specifically, we have identified this factor to be a key upstream mediator in the development of this inflammatory skin disease. Using a genetically tractable transgenic mouse model system, we demonstrate that overexpression of ΔNp63 in the basal keratinocytes of the epidermis results in a severe skin phenotype consisting of epidermal hyperplasia, diminished terminal differentiation, Th2 inflammation and a marked increase in immune cell infiltration52 – sharing many of the key pathological and molecular features associated with human AD lesions, which are also associated with elevated ΔNp63 expression.

In addition to altered keratinocyte functions, AD is also viewed as an immune-mediated disease with elevated Th2 cytokines as a telltale feature. Although we observed an overall preferential skewing toward Th2 cytokine production in adult lesional mouse skin, one particularly striking finding was the elevated expression levels of the pro-Th2 cytokine, IL-33 after a very short induction time of ΔNp63 expression. Thus, the skewing toward a Th2 cell subset could be an early event in AD disease pathogenesis caused by elevated levels of IL-33 a known player in the pathogenesis of AD6, 7, 8, 40 and a direct transcriptional target of ΔNp63 (this study). In addition to increased Th2 cytokine production, patients with AD typically demonstrate elevated levels of the itch-inducing cytokine IL-31, together with its receptors IL-31ra and OSMR. Although IL-31 is not considered a driver of AD pathogenesis, the effects of itch nonetheless contribute to the barrier and immune defects commonly associated with this disease. For example, IL-31 expression has been shown to interfere with keratinocyte differentiation and scratching is known to directly disrupt skin-barrier function and contribute to AD disease severity and progression.53 Moreover, there is growing evidence that pruritus and the effects of scratching can lead to Th2-skewed conditions in the skin thereby contributing to AD pathogenesis.54 Together, the effects of elevated IL-31, IL-31ra and OSMR, all shown in this report to be direct targets of ΔNp63 create a vicious cycle of itching, scratching and localized irritation/inflammation in a manner that is highly characteristic of human AD.

Given the master regulatory functions of ΔNp63 and the complex etio-pathology of AD, we suspect that the ΔNp63-AD link might be more extensive than what we have described here. This is quite evident from the broad transcriptomic changes, resulting from dysregulated ΔNp63 expression as shown by our RNA-seq studies and from recent studies on human keratinocytes and AD patients. Indeed, siRNA-mediated knockdown of p63 in human keratinocytes results in enhanced TSLP signaling and elevated expression levels of the tight junction protein claudin4 – both of which have been linked to AD.55, 56 In a complementary study with human AD patient skin, Kubo et al.55 identified a sub-population of low-expressing ΔNp63+ keratinocytes, which act in an autocrine and/or paracrine loop to generate TSLP and promote chronic inflammation. Importantly, consistent with our results, this study also identified a large population of highly expressing ΔNp63+ keratinocytes in human AD lesional skin. Together, these findings allude to a highly complex temporal-spatial relationship between ΔNp63 expression and inflammatory conditions such as AD in both mouse and human skin.

In summary, AD has long been characterized as a disease resulting from impaired keratinocyte function and immune defects. Although the role of bone marrow-derived immune cells in AD has received much attention, the broader effects mediated by keratinocytes have been under appreciated. Here we provide evidence that epidermal overexpression of ΔNp63 can result in an activated keratinocyte state, which serves as the initial trigger in unleashing a number of signaling cascades involved in the development of AD. Most notably, ΔNp63 hyperactivity has a direct effect on IL-33 and IL-31 expression, which in turn lead to downstream Th2 immune cell activation and pruritis, respectively (see model in Figure 7). Our data suggest that ΔNp63 is positioned as a central and upstream player in regulating critical facets of AD by controlling a broad repertoire of immunoregulators and keratinocyte terminal differentiation genes, which together, contribute to disease pathogenesis. This important role of ΔNp63 as a molecular ‘driver’ is further supported by the fact that the skin phenotype observed in the ΔNp63 mice is reversible. The exciting causative link between ΔNp63 and AD raises the intriguing possibility of manipulating ΔNp63 levels or activity as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of this skin disease.

Functional interplay between ΔNp63 and immune activation, itch and defects in keratinocyte terminal differentiation in AD. This model depicts the role ΔNp63 plays in directing various components involved in the development of atopic dermatitis. Elevated expression levels of ΔNp63 results in direct activation of IL-33 signaling and subsequent Th2 polarization. Induction of pruritus occurs through direct regulation of IL-31, IL-31ra and OSMR gene expression. Elevated ΔNp63 epidermal expression, scratching response to pruritus and Th2 cell activation all contribute to alterations in keratinocyte terminal differentiation

Materials and Methods

Generation of transgenic animals and transgene induction

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with Roswell Park Cancer Institute IACUC regulations. The ΔNp63 responder transgenic line17 and the K5-tTa driver transgenic mice57 were crossed to generate bi-transgenic (BG) mice. Induction of the ΔNp63α transgene in adult mice and embryos has been previously described.17, 52 Toe suppress ΔNp63 transgene expression during embryogenesis and early post-natal development, pregnant dams were administered doxycycline in rodent chow (Bio-Serve, Flemington, NJ, USA). Transgene expression was then induced in ΔNp63BG mice at weaning by doxycycline withdrawal.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (Romano et al., 2009). Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: HA (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1 : 5000), RR-14 (1 : 5000)58 and GAPDH (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA, 1 : 30000). Quantification of ΔNp63 protein expression levels was performed using ImageJ software. Values were normalized to GAPDH.

Immunofluorescence

Stainings using paraffin-embedded mouse dorsal skin sections and human skin were performed as previously described.30 Primary antibodies used at indicated dilutions were ΔNp63 (RR-14, 1 : 50),58 K5, K1, filaggrin, involucrin and loricrin (1 : 200; gift from Dr. Julie Segre), IL-33 (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA, 1 : 50), K14 (1 : 200; Romano Laboratory, Buffalo, NY, USA).

Clinical observations

The skin of control and ΔNp63BG mice was examined for skin lesions and clinical scores for disease severity were recorded as described with slight modifications.59, 60, 61 In brief, total clinical severity scores for AD-like lesions were defined as the sum of the individual scores graded as the following: 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe) for each of the five signs and symptoms (itch, erythema, edema, excoriation/erosions and scaling/dryness/lichenification). Symptoms were monitored at various time points.

ELISA

For measurement of total IgE, blood samples were collected and IgE levels were measured in triplicates using the Mouse IgE ELISA MAX Deluxe kit (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasmids and transfection

Plasmids encoding WT ΔNp63α and ΔNp63αMT were cloned in the retroviral plasmid MIGR1. The plasmid pCL-Eco62 was co-transfected with viral plasmids to increase titers using Fugene-6 transfection reagent, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell lines

The retroviral packaging cell line platinum-E (Plat-E) was maintained in DMEM supplemented with FBS, antibiotics, glutamine, blasticidin and puromycin. Plat-E cells were switched to medium lacking blasticidin and puromycin a day before transfection. Mouse keratinocytes were obtained from CELLnTEC and were grown in CnT-07CF media (Bern, Switzerland).

Retroviral production and transduction

For production of retrovirus, the Plat-E packaging cell line was transfected with various retroviral plasmids along with the helper plasmid pCL-Eco. Retroviral supernatants were harvested at 48 h post transfection. For retroviral infection, mouse keratinocytes were spin inoculated with retroviral supernatant in the presence of 10 μg/ml Polybrene. Two days after infection, cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated.

Measurement of scratching behavior

Spontaneous scratching behavior was measured for 5 min during which time the number of scratches were counted. This was followed by a 10-min break in counting. This was repeated three times for each mouse analyzed. A total of 10 BG and 10 control mice were used for these studies. One scratch was defined as the animal lifting a hind paw from the cage floor, scratching with the paw and then returning the paw to the cage floor.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as mean±S.D. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test with unequal variance assumption.

RNA-seq analysis

Dorsal skin from WT and transgenic mice were dissected and treated with dispase at 37 °C for 1 h to separate the epidermis from dermis. Epidermal samples were washed and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to established protocols. RNA meeting quality standards (>8.0) were utilized as input for RNA-seq using Illumina’sTru-seq low-throughput multiplex protocol, as described previously.26 Two biological replicates each for both WT and BG mouse epidermis were sequenced in parallel using an Illumina HiSeq 2500, with 50 cycle single-end read reactions. Sequencing reads were aligned to transcript annotations for the mm10 genome using the TopHat alignment algorithm run with default parameters (version 2.0.7) and Illumina’s custom iGenomes annotation file ‘gene.gtf’ available at http://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/igenome.html.

A weighted, average abundance for each annotated gene-level transcript was then calculated for each experimental condition (WT, BG) as Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped (FPKM), using the Cufflinks algorithm (version 2.1.1).63 Upon confirmation that all samples were enriched for genes specifically expressed in the epidermis, fold-change in expression, between conditions (BG/WT), were then calculated for each gene probe, along with a multiple-testing corrected significance estimate (q-value) for differential expression, utilizing the Cuffdiff algorithm (version 2.1.1).64

Significant DEGs were identified by the Cuffdiff algorithm as having a q<0.05, with overly complex, shallowly sequenced and/or over-amplified (i.e., PCR artifacts) removed from this analysis. In addition, to avoid over-estimation of differential expression among lowly expressed genes in one or both conditions, only DEGs with an FPKM≥ experimental median for both conditions (WT and BG) were included in downstream analysis. DEGs for epidermis meeting the above criteria (n=1901) were used as input for canonical signaling pathway and biological function enrichment testing using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis’s existing subscription annotation database, available at http://www.ingenuity.com/products/ipa (Figure 2a and c, respectively). In addition, a greedy approach was taken, in which the fold-change of near-significant DEGs (fold-change >4), meeting the aforementioned quality criteria, were also included to more closely examine the expression behavior of genes annotated to specific canonical signaling pathways of interest, identified in Figure 2a (see Figure 2b). Average experimental gene expression values (FPKM) and significance of fold-change expression between conditions (TG/WT; −log10[q‐value]) for individual DEGs of interest is visualized in Figure 2c using the Java Treeview program.65 Hypergeometric enrichment testing (Figure 2c) was performed using lentient (Fisher’s Exact testing, Dark purple) and strict approaches (Benjamini–Hochberg multiple-testing corrected, light purple). q-value=−log10 (Bon-feronni corrected P-value).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from adult WT and transgenic mouse skin or from human skin biopsy of healthy and human AD lesion of AD participants was isolated and purified using TRIZol (Invitrogen) according to established protocols. Two micrograms of total RNA from mouse skin or 400 ng of total RNA from human skin biopsy was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was performed on an iCycler iQ PCR machine using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). All real-time RT-PCR assays were performed in triplicate in at least two independent experiments using two different animal samples. Relative expression values of each target gene were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression. A list of the primers is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Mouse keratinocytes were obtained from CELLnTEC and grown to 80% confluency in CnT-07CF media (CELLnTEC, Bern). Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and processed by the Magna ChIP G Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore). Antibodies used were RR-14,58 H129 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA) and normal rabbit IgG. Purified immunoprecipitated DNA was used for real-time qPCR.

Human skin samples

All studies were approved by the Research Subject Review Boards at the University of Rochester Medical Center and/or by the Research Subject Review Boards at the Johns Hopkins University. All subjects gave written informed consent. The diagnosis of AD was made using the US consensus conference criteria.66 All subjects underwent a 5-mm punch biopsy from a lesional site. Normal skin was obtained from 6mm punch biopsies of the buttock area from random volunteers who all gave written informed consent. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. AD lesion skin (n=8), AD non-lesional skin (n=8) and normal skin (n=8).

Study approval

Written informed consent was received from participants prior to inclusion in the study. Institutional review board approval was obtained at the University of Rochester. All protocols involving animals were approved by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute IACUC.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

atopic dermatitis

- Th1:

-

type 1 T helper

- Th2:

-

type 2 T helper

- TSLP:

-

thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- K14:

-

keratin14

- K1:

-

keratin1

- Flg:

-

filaggrin

- Lor:

-

loricrin

- Ivl:

-

involucrin

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA-sequencing

- DEGs:

-

differentially expressed genes

- TLR:

-

toll-like receptors

- ENCODE:

-

encyclopedia of DNA elements

- NHEK:

-

normal human epidermal keratinocytes

References

Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD, Nomura I, Hamid QA . New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 2004; 113: 651–657.

Leung DY, Bieber T . Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2003; 361: 151–160.

Bieber T . Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1483–1494.

Boguniewicz M, Leung DY . Atopic dermatitis: a disease of altered skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Immunol Rev 2011; 242: 233–246.

Irvine AD, McLean WH, Leung DY . Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1315–1327.

Savinko T, Matikainen S, Saarialho-Kere U, Lehto M, Wang G, Lehtimaki S et al. IL-33 and ST2 in atopic dermatitis: expression profiles and modulation by triggering factors. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132: 1392–1400.

Imai Y, Yasuda K, Sakaguchi Y, Haneda T, Mizutani H, Yoshimoto T et al. Skin-specific expression of IL-33 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cells and elicits atopic dermatitis-like inflammation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 13921–13926.

Salimi M, Barlow JL, Saunders SP, Xue L, Gutowska-Owsiak D, Wang X et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J Exp Med 2013; 210: 2939–2950.

Chan LS, Robinson N, Xu L . Expression of interleukin-4 in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in a pruritic inflammatory skin disease: an experimental animal model to study atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2001; 117: 977–983.

Zheng T, Oh MH, Oh SY, Schroeder JT, Glick AB, Zhu Z . Transgenic expression of interleukin-13 in the skin induces a pruritic dermatitis and skin remodeling. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129: 742–751.

Zhu Z, Oh MH, Yu J, Liu YJ, Zheng T . The Role of TSLP in IL-13-induced atopic march. Sci Rep 2011; 1: 23.

Pignon JC, Grisanzio C, Geng Y, Song J, Shivdasani RA, Signoretti S . p63-expressing cells are the stem cells of developing prostate, bladder, and colorectal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 8105–8110.

Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 1999; 398: 714–718.

Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A . p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 1999; 398: 708–713.

Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, Martinelli E, Fantozzi I, Bondanza S et al. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 3156–3161.

Senoo M, Pinto F, Crum CP, McKeon F . p63 Is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell 2007; 129: 523–536.

Romano RA, Smalley K, Liu S, Sinha S . Abnormal hair follicle development and altered cell fate of follicular keratinocytes in transgenic mice expressing DeltaNp63alpha. Development 2010; 137: 1431–1439.

van Bokhoven H, McKeon F . Mutations in the p53 homolog p63: allele-specific developmental syndromes in humans. Trends Mol Med 2002; 8: 133–139.

Ha L, Ponnamperuma RM, Jay S, Ricci MS, Weinberg WC . Dysregulated DeltaNp63alpha inhibits expression of Ink4a/arf, blocks senescence, and promotes malignant conversion of keratinocytes. PLoS One 2011; 6: e21877.

Yang X, Lu H, Yan B, Romano RA, Bian Y, Friedman J et al. DeltaNp63 versatilely regulates a Broad NF-kappaB gene program and promotes squamous epithelial proliferation, migration, and inflammation. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 3688–3700.

Lu H, Yang X, Duggal P, Allen CT, Yan B, Cohen J et al. TNF-alpha promotes c-REL/DeltaNp63alpha interaction and TAp73 dissociation from key genes that mediate growth arrest and apoptosis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 6867–6877.

Gu X, Lundqvist EN, Coates PJ, Thurfjell N, Wettersand E, Nylander K . Dysregulation of TAp63 mRNA and protein levels in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126: 137–141.

Shen CS, Tsuda T, Fushiki S, Mizutani H, Yamanishi K . The expression of p63 during epidermal remodeling in psoriasis. J Dermatol 2005; 32: 236–242.

Kim SY, Cho HJ, Kim DS, Choi HR, Kwon SB, Na JI et al. Differential expression of p63 isoforms in normal skin and hyperproliferative conditions. J Cutan Pathol 2009; 36: 825–830.

Romano RA, Smalley K, Magraw C, Serna VA, Kurita T, Raghavan S et al. {Delta}Np63 knockout mice reveal its indispensable role as a master regulator of epithelial development and differentiation. Development 2012; 139: 772–782.

Rizzo JM, Romano RA, Bard J, Sinha S . RNA-seq studies reveal new insights into p63 and the transcriptomic landscape of the mouse skin. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 135: 629–632.

Shalom-Feuerstein R, Lena AM, Zhou H, De La Forest Divonne S, Van Bokhoven H, Candi E et al. DeltaNp63 is an ectodermal gatekeeper of epidermal morphogenesis. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18: 887–896.

Chakravarti D, Su X, Cho MS, Bui NH, Coarfa C, Venkatanarayan A et al. Induced multipotency in adult keratinocytes through down-regulation of DeltaNp63 or DGCR8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: E572–E581.

Dillon SR, Sprecher C, Hammond A, Bilsborough J, Rosenfeld-Franklin M, Presnell SR et al. Interleukin 31, a cytokine produced by activated T cells, induces dermatitis in mice. Nat Immunol 2004; 5: 752–760.

Romano RA, Ortt K, Birkaya B, Smalley K, Sinha S . An active role of the DeltaN isoform of p63 in regulating basal keratin genes K5 and K14 and directing epidermal cell fate. PLoS One 2009; 4: e5623.

Leung DY . New insights into atopic dermatitis: role of skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Allergol Int 2013; 62: 151–161.

Tokura Y . Extrinsic and intrinsic types of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci 2010; 58: 1–7.

Guttman-Yassky E, Suarez-Farinas M, Chiricozzi A, Nograles KE, Shemer A, Fuentes-Duculan J et al. Broad defects in epidermal cornification in atopic dermatitis identified through genomic analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124: 1235–44 e58.

Suarez-Farinas M, Tintle SJ, Shemer A, Chiricozzi A, Nograles K, Cardinale I et al. Nonlesional atopic dermatitis skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127: 954–964, e1–4.

Kuo IH, Carpenter-Mendini A, Yoshida T, McGirt LY, Ivanov AI, Barnes KC et al. Activation of epidermal toll-like receptor 2 enhances tight junction function: implications for atopic dermatitis and skin barrier repair. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 988–998.

Laouini D, Alenius H, Bryce P, Oettgen H, Tsitsikov E, Geha RS . IL-10 is critical for Th2 responses in a murine model of allergic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 1058–1066.

Gharagozlou M, Farhadi E, Khaledi M, Behniafard N, Sotoudeh S, Salari R et al. Association between the interleukin 6 genotype at position -174 and atopic dermatitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2013; 23: 89–93.

Koren Carmi I, Haj R, Yehuda H, Tamir S, Reznick AZ . The role of oxidation in FSL-1 induced signaling pathways of an atopic dermatitis model in HaCaT keratinocytes. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015; 849: 1–10.

Brandt EB, Sivaprasad U . Th2 cytokines and atopic dermatitis. J Clin Cell Immunol 2011; 2: 3.

Nakae S, Morita H, Ohno T, Arae K, Matsumoto K, Saito H . Role of interleukin-33 in innate-type immune cells in allergy. Allergol Int 2013; 62: 13–20.

Grimstad O, Sawanobori Y, Vestergaard C, Bilsborough J, Olsen UB, Gronhoj-Larsen C et al. Anti-interleukin-31-antibodies ameliorate scratching behaviour in NC/Nga mice: a model of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 2009; 18: 35–43.

Szegedi K, Kremer AE, Kezic S, Teunissen MB, Bos JD, Luiten RM et al. Increased frequencies of IL-31-producing T cells are found in chronic atopic dermatitis skin. Exp Dermatol 2012; 21: 431–436.

Bilsborough J, Leung DY, Maurer M, Howell M, Boguniewicz M, Yao L et al. IL-31 is associated with cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive skin homing T cells in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: 418–425.

Consortium EP. A user's guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE). PLoS Biol 2011; 9: e1001046.

Kouwenhoven EN, van Heeringen SJ, Tena JJ, Oti M, Dutilh BE, Alonso ME et al. Genome-wide profiling of p63 DNA-binding sites identifies an element that regulates gene expression during limb development in the 7q21 SHFM1 locus. PLoS Genet 2010; 6: e1001065.

Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 2007; 129: 823–837.

Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ et al. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell 2005; 120: 169–181.

Consortium EP, Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 2007; 447: 799–816.

Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 311–318.

Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD, Kheradpour P, Stark A, Harp LF et al. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature 2009; 459: 108–112.

Romano RA, Birkaya B, Sinha S . A functional enhancer of keratin14 is a direct transcriptional target of deltaNp63. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127: 1175–1186.

Du J, Romano RA, Si H, Mattox A, Bian Y, Yang X et al. Epidermal overexpression of transgenic DeltaNp63 promotes type 2 immune and myeloid inflammatory responses and hyperplasia via NF-kappaB activation. J Pathol 2014; 232: 356–368.

Cornelissen C, Marquardt Y, Czaja K, Wenzel J, Frank J, Luscher-Firzlaff J et al. IL-31 regulates differentiation and filaggrin expression in human organotypic skin models. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129: 426–433, 33, e1–8.

Stott B, Lavender P, Lehmann S, Pennino D, Durham S, Schmidt-Weber CB . Human IL-31 is induced by IL-4 and promotes TH2-driven inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132: 446–454, e5.

Kubo T, Kamekura R, Kumagai A, Kawata K, Yamashita K, Mitsuhashi Y et al. DeltaNp63 controls a TLR3-mediated mechanism that abundantly provides thymic stromal lymphopoietin in atopic dermatitis. PLoS One 2014; 9: e105498.

Kubo T, Sugimoto K, Kojima T, Sawada N, Sato N, Ichimiya S . Tight junction protein claudin-4 is modulated via DeltaNp63 in human keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 455: 205–211.

Diamond I, Owolabi T, Marco M, Lam C, Glick A . Conditional gene expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the tetracycline-regulated transactivators tTA and rTA linked to the keratin 5 promoter. J Invest Dermatol 2000; 115: 788–794.

Romano RA, Birkaya B, Sinha S . Defining the regulatory elements in the proximal promoter of DeltaNp63 in keratinocytes: Potential roles for Sp1/Sp3, NF-Y, and p63. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126: 1469–1479.

Leung DY, Hirsch RL, Schneider L, Moody C, Takaoka R, Li SH et al. Thymopentin therapy reduces the clinical severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1990; 85: 927–933.

Akei HS, Brandt EB, Mishra A, Strait RT, Finkelman FD, Warrier MR et al. Epicutaneous aeroallergen exposure induces systemic TH2 immunity that predisposes to allergic nasal responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: 62–69.

Matsuda H, Watanabe N, Geba GP, Sperl J, Tsudzuki M, Hiroi J et al. Development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesion with IgE hyperproduction in NC/Nga mice. Int Immunol 1997; 9: 461–466.

Naviaux RK, Costanzi E, Haas M, Verma IM . The pCL vector system: rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J Virol 1996; 70: 5701–5705.

Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc 2012; 7: 562–578.

Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L . Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31: 46–53.

Saldanha AJ . Java Treeview—extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 2004; 20: 3246–3248.

Eichenfield LF . Consensus guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2004; 59 (Suppl 78): 86–92.

Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012; 489: 57–74.

Yue F, Cheng Y, Breschi A, Vierstra J, Wu W, Ryba T et al. A comparative encyclopedia of DNA elements in the mouse genome. Nature 2014; 515: 355–364.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by a NIH grant 1R03AI115407 (to R-A Romano).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by G Melino

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rizzo, J., Oyelakin, A., Min, S. et al. ΔNp63 regulates IL-33 and IL-31 signaling in atopic dermatitis. Cell Death Differ 23, 1073–1085 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2015.162

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2015.162

- Springer Nature Limited